?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

On the β plane approximation, the two-layer quasigeostrophic mode is used to study the baroclinic instability of the quadric shear basic zonal flows on a uniform bottom topography. The phase speed and growth rate of instability waves are functions of the shear zonal basic flows and bottom topographic slope. The study focus is on the effects of topography and the quadric shear basic zonal flows (the second derivative of basic zonal flows is not zero). The meridional slope destabilise (stabilise) zonal flows, it plays an unstable role in disturbance, moreover the effect of the second derivative of basic zonal flows is to accelerate the instability of disturbance. The zonal slope always destabilises the zonal basic flows through zonal and meridional wavenumber. Moreover, the effect of the second derivative of basic zonal flows is to accelerate the instability of disturbance.

1. Introduction

Baroclinic instability of oceanic currents could yield the right orders of magnitude of the properties of the Gulf Stream eddies, In a macroscale background current the original condition of eddy development is depicted through the rapid growth of infinitely small orthogonal mode perturbations, which can, owing to their spatial and time structure, efficiently obtain energy from the large-scale background state (Pedlosky, Citation1978; Cushman-Roisin, Citation1986). The physical mechanism of eddy generation depends on the mean potential vorticity (PV) gradient, which is prerequisites large-scale flows for unstable and nonlinear evolution of eddying flows. Although the planetary vorticity gradient β is small, the nonlinear dynamics of the instability waves very susceptible to the β effect as has been proved in an earlier research, it is further found that the β effect inclines to preserve the instability point at the primary of the solution phase plane from the solution trajectories (Pedlosky, Citation1981). Chraney (Citation1974) and Eady (Citation1949) formulated a model baroclinic instability, they indicated that the disturbance viewed in the atmosphere and ocean could be interpreted as a manifestation of baroclinic instability of the basic zonal flows. A simple two-layer model with small vertical scale to remove interference was first introduced by Phillips (Citation1954). Pedlosky(Citation1987) used Phillips’ model to study nonzonal basic flows with a flat bottom topography, he showed that the nonzonal basic flows would not possess a minimum critical shear for instability. More recently, Pedlosky studied the evolution of baroclinic instability wave in spatial and time structure, when the disturbance shifts downstream from an upstream source of perturbation energy such as might take place in flows like the separated Gulf Stream (Pedlosky, Citation2011, Citation2019).

A central question in the theory of atmosphere and ocean instability barotropic and baroclinic modes are modified by the presence of the basic flows shear or variable topography. The influence of bottom topography on large-scale atmospheric and oceanic flows have formed the theme for a large number of meteorological and ocean station investigations. The bottom topography were studied by many researchers (Rhines and Bretherton, Citation1973; McWilliams, Citation1974; Patoine and Warn, Citation1982), who demonstrate that it can strongly adapt to the dynamics of waves in the ocean, the role of bottom slope is similar to the β effect, which generally assists stabilise the zonal basic flows by modifying the back ground PV gradient (Blumsack and Gierasch, Citation1972; Steinsaltz, Citation1987). Hart demonstrated that a one-way zonal slope has a equilibrium effect on a circular vortex and forms an asymmetric mean flows in a two-layer quasigeostrophic (QG) model on f plane (Hart, Citation1975a, Citation1975b). Benilon has shown that short-scale bottom topography irregularities can stabilise the current (Benilov, Citation2001). On the β plane approximation, Chen and Kamenkovich (Citation2013) used a two-layer QG model, they obtained the important effect of bottom topography on the baroclinic instability of basic zonal currents. They found the topographic slope powerful affects the instability scale, showing that a positive topographic slope can lead to a large scale of most instability wave, whilst a negative topographic slope is easy to make the wave with the maximum growth rate changes a smaller scale. Many studies only consider the influence of zonal basic flows or nonzonal basic flows and topography on baroclinic instability, in addition, the deviation of most instability is litter consideration on the combined effect of the quadric shear basic zonal flows and topographic slope on the β plane approximation (Leng and Bai, Citation2018).

In this study, the quadric shear basic zonal flows and bottom slope were considered on the β plane approximation, to examine it and the topography effects on the linear baroclinic instability. This paper is organised as follows: a two-layer model of the quadric shear basic zonal flows is described in Section 2; Under the quadric shear basic zonal flows, a necessary instability condition and the dispersion relation for instability model are derived and the second derivative of basic zonal flows, topographic slope effects are discussed in Section 3. In Section 4, Conclusions are drawn in section.

2. The model

A two-layer potential vorticity (PV) equation with topography on the β plane approximation (Geoffrey and Vallis, Citation2006)

(1)

(1)

where qn is potential vorticity, the subscript refers to the layer; the upper layer corresponds to n = 1, and the lower to n = 2.

is the Jacobian operator. Potential vorticity qn are of the form on the β plane approximation

(2)

(2)

where β is the planetary vorticity gradient, Hn is the depth of two-layer fluid,

is the spatially varying elevation of bottom topography,

square of the inverse Rossby radius, f0 is the Coriolis parameter,

is the reduced gravity,

is the Kronecker symbol,

Consider the streamfunction ψn in the upper layer and lower layer:

(3)

(3)

where

describe disturbances,

is the quadric shear basic zonal flows (

) in the upper layer. The potential vorticity qn is expressed through the streamfunction ψn as follows:

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

We define

For convenience, let

The square of the inverse Rossby radius Fn follows that

(6)

(6)

3. Instability analytical study

3.1. Necessary instability condition with quadric shear basic zonal flows and bottom topography

The perturbation equations for are obtained by linearising the PV Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1) :

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

where

sx and sy are the same as employed in Chen and Kamenkovich (Citation2013). The normal-mode solution

(9)

(9)

where An is the amplitude in each layer, (k, l) is the wavenumber, and ω is the frequency of the disturbance. Inserting EquationEq. (9)

(9)

(9) into EquationEqs. (7)

(7)

(7) and Equation(8)

(8)

(8) leads to two coupled algebraic equations for An:

(10)

(10)

(11)

(11)

where

it represents the vertical shear of the basic zonal flow,

and

are the wave vector and topographic slope, respectively. For obtain a necessary instability condition. Multiplying EquationEqs. (10)

(10)

(10) and Equation(11)

(11)

(11) by

and

respectively.

(12)

(12)

(13)

(13)

where

is phase speed,

are the complex conjugates of An. Summing up EquationEqs. (12)

(12)

(12) and Equation(13)

(13)

(13) , we obtain

(14)

(14)

The imaginary part of EquationEq. (14)(14)

(14)

(15)

(15)

where ωi is the imaginary part of ω. If k is not zero, the instability necessary conditions with the basic zonal flows quadric sheared and bottom topography on the β plane approximation.

(16)

(16)

EquationEquation (16)(16)

(16) is the ordinary result, it consists of some special cases.

Case one:

If namely the basic zonal flows Un is not the quadric shear, the instability necessary conditions,

It is similar to the results of Chen and Kamenkovich (Citation2013).

Case two:

In the absence of topography and the baroclinic instability is determined by the second derivative of quadric shear basic zonal flows, stratification effect and the planetary vorticity gradient β;

Case three:

If the gradient of the basic state absolute vorticity that is to say, the basic velocity distribution must be such that

is able to over-balance planetary vorticity β to make Pn change its sign, especially we shall consider the simplest case of the basic zonal flows

(where

are constant). Pedlosky (Citation1987) shows that the absolute vorticity

must be positively;

Case four:

When the topography is a east-west topography, is simplified to Sy, if the topographic slope Sy is the southward slope

it can stabilise the basic zonal flow through changing the background PV gradient

the topographic slope is the northward slope

it is the opposite of the northward slope. When the topography is north-south, it effect on the basic zonal flows through changing

in EquationEq. (16)

(16)

(16) ,

is simplified to

and is dependent of the north-south direction slope, the wavevector magnitude and orientation.

3.2. The dispersion relation with the quadric shear basic zonal flows and bottom topography

Nontrivial solutions for A1 and A2 of EquationEqs. (10)(10)

(10) and Equation(11)

(11)

(11) exist only if the determinant of coefficients is zero. This condition yields the dispersion relation

(17)

(17)

EquationEq. (17)(17)

(17) yields a quadratic equation for ω,

(18)

(18)

where

here

We can get the phase speed and growth rate of unstable wave with the quadric shear basic zonal flows and topographic effects on the β plane approximation, the discriminant of ω derived from EquationEq. (18)

(18)

(18) is

(19)

(19)

Once the phase speed can be written in a complex form:

where

(20)

(20)

(21)

(21)

The cr is a nonlinear function of and S for a given perturbation with the wavenumber K, whilst

are composed of the nonlinear terms. Aside from the terms associated with

EquationEqs. (20)

(20)

(20) and Equation(21)

(21)

(21) are the same as the results of Chen and Kamenkovich (Citation2013). Using Equationequation (20)

(20)

(20) , we will analyse the effects of the interplay between the second derivative of quadric shear basic zonal flows and topography on the linear baroclinic instability.

3.2.1. Meridional slope and the quadric shear basic zonal flows on the β plane:

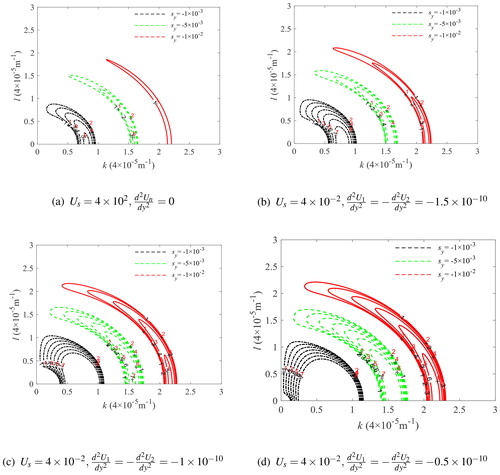

When the slope is only meridional, S reduces to Sy. depicts Chen and Kamenkovich’s result (2013), shows the growth rate as a function of the wavenumber (k, l) and bottom slope for the he quadric shear basic zonal flows:

(Geoffrey and Vallis, Citation2006) over three northward slopes: weak intermediate

and strong

The growth rate of an instability wave depends on the magnitude k, l, topographic slope and the quadric shear basic zonal flows, the instability stable waves are shown here within an incomplete annulus in the (k, l) plane. The greatest growth rate is the same as employed in Chen and Kamenkovich (Citation2013) and Leng and Bai (Citation2018), it is found at l = 0, the most instability mode is a meridional noodle mode. Compare with , as the meridional slope gets steeper, the second derivative of quadric shear basic zonal flows is gradually reduced, the unstable wavenumber rang moves away from the origin in the (k, l) plane, indiction shorter zonal and meridional wavelengths of the unstable modes, and becomes narrower. In addition, shows that the smaller second derivative of quadric shear basic zonal flows can be used to the narrower the width of noodle mode. The results for south slope are also similar and not discussed here.

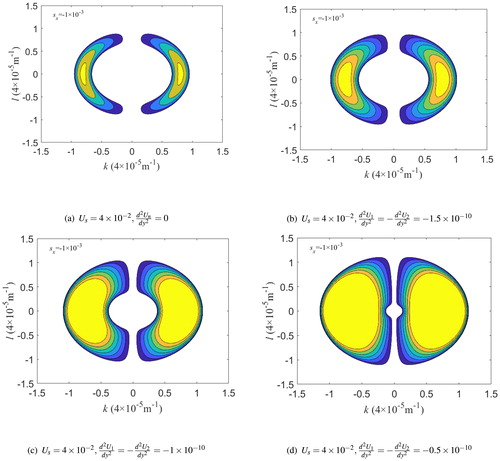

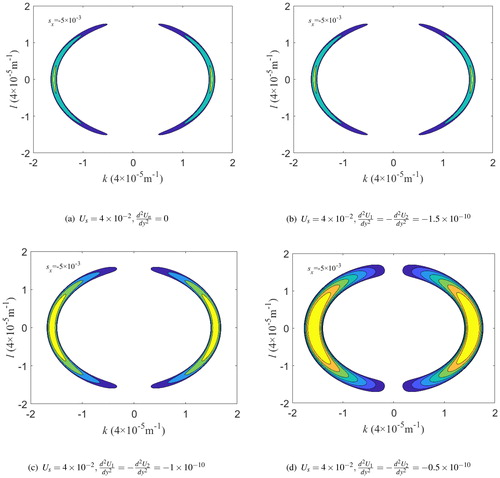

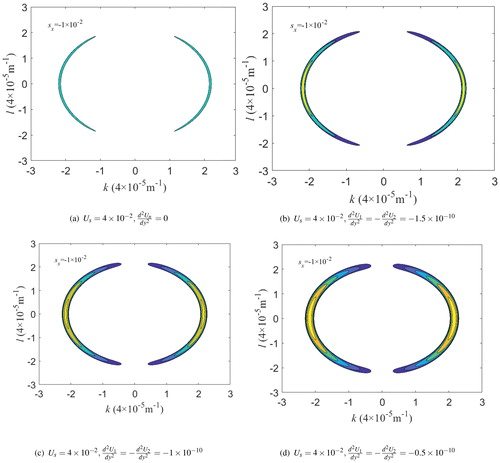

3.2.2. Zonal slope and the quadric shear basic zonal flows on the β plane:

Chen and Kamenkovich (Citation2013) has verified that positive (west slope) and negative (east slope) have the same effects on the greatest growth rate and the corresponding phase speed. Thus, we also consider west slope in the following analysis. The effects of a zonal slope are considered for the quadric shear basic zonal flows om slope for the he quadric shear basic zonal flows: and the westward slope

and show the basic zonal flows

and

at the different zonal slopes, respectively. show that these different zonal topographic slopes are not like a meridional topographic slope on β plane, it modifies the shape of the instability mode, which is no longer the meridional oriented noodle mode, the range model is the circular, and range of instability wavennumber shrinks as slope magnitude increases. show the smaller values of the zonal slope correspond to very narrow unstably wavenumber ranges with the same the zonal basic flows Un.

In contrast of , as shown in , if the basic zonal flows is the quadric shear basic zonal flows, the effects of are increase the number of unstable wavenumbers areas. But in the range of unstable wavenumbers does not change when

increases, this is totally different from the meridional slope of state.

4. Conclusions

The present analysis demonstrates that the bottom topography and the quadric shear basic zonal flows in the baroclinic unstable of oceanic model. We obtained the following conclusions.

(1) Topographic slopes and the quadric shear basic zonal flows are confirmed that it can modify stability of basic zonal flows, through the changes in the background PV gradient on the β plane approximation.

(2) The topographic slope is only meridional slope, the instability mode has the shape of a noodle mode, the width of noodle decreases as the meridional slope (north slope) increases, this illustration that the north slope always plays on unstable role. The function second derivative of quadric shear basic zonal flows () are to keep the noodle mode away from (k, l) plane, when it increase, the width of the mode region become more and more narrow. Therefore, the decrease of

and the steepening of slope have the same effect on the instability.

(3) The topographic slope is purely zonal in (k, l) plane, if is zero, namely, the basic zonal is not the quadric shear, the unstable range gradually shrinks as the slope magnitude increases; if the basic zonal flows is the quadric shear (

), the number of instability regions are increased, that is, expand the area of unstable regions. But under the same slope, the change of the quadric shear basic zonal flows does not affect the unstable range.

The results of this idealised study are complementary to the literatures (Chen and Kamenkovich, Citation2013; Leng and Bai, Citation2018), it can help to interpret the large-scale waves generation over basic zonal flows sheared and more complex topography in the real ocean and atmosphere. More detailed work including nonzonal basic flows, vertical shear in zonal ocean currents, and theoretical study will be considered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benilov, E. S. 2001. Baroclinic instability of two-layer flows over one-dimensional bottom topography. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 31, 2019–2025. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(2001)0312.0.CO;2 doi:10.1175/1520-0485(2001)031<2019:BIOTLF>2.0.CO;2

- Blumsack, S. L. and Gierasch, P. J. 1972. Mars: The effects of topography on baroclinic instability. J. Atmos. Sci. 29, 1081–1089. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1972)029<1081:MTEOTO>2.0.CO;2

- Chen, C. and Kamenkovich, I. 2013. Effects of topography on baroclinic instability. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43, 790–804. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-12-0145.1

- Chraney, J. G. 1974. The dynamics of long waves in a baroclinic westerly current. J. Meterorol. 4, 136–162.

- Cushman-Roisin, B. 1986. Frontal geostrophic dynamics. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 16, 132–143. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1986)016<0132:FGD>2.0.CO;2

- Eady, E. T. 1949. Long waves and cyclone waves. Tellus 1, 33–52.

- Geoffrey, K. and Vallis, 2006. Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 212–213.

- Hart, J. E. 1975a. Baroclinic instability over a slope. Part I: Linear theory. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 5, 625–633. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1975)005<0625:BIOASP>2.0.CO;2

- Hart, J. E. 1975b. Baroclinic instability over a slope. Part II: Finite-amplitude theory. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 5, 634–641. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1975)005<0634:BIOASP>2.0.CO;2

- Leng, H. and Bai, X. 2018. Baroclinic instability of nonzonal flows and bottom slope effects on the propagation of most unstable wave. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 48, 2923–2936. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-18-0087.1

- McWilliams, J. C. 1974. Forced transient flows and small-scale topography. Geophys. Fluid Dyn. 6, 49–79. doi:10.1080/03091927409365787

- Patoine, A. and Warn, T. 1982. The Interaction of long, quasi-stationary baroclinic waves with topography. J. Atmos. Sci. 39, 1018–1025.

- Pedlosky, J. 1978. A nonlinear model of the onset of upwelling. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 8, 178–187. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1978)008<0178:ANMOTO>2.0.CO;2

- Pedlosky, J. 1981. Resonant topographic waves in barotropic and baroclinic flows. J. Atmos. Sci. 38, 2626–2641. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1981)038<2626:RTWIBA>2.0.CO;2

- Pedlosky, J. 1987. Geophysical Fluid Dynamics. 2nd ed. New York: Springer, 710 pp.

- Pedlosky, J. 2011. The nonlinear downstream development of baroclinic instability. J. Mar. Res. 69, 750–722.

- Pedlosky, J. 2019. The Effect of beta on the downstream development of unstable chaotic baroclinic waves. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 49, 2337–2343. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-19-0097.1

- Phillips, N. A. 1954. Energy transformations and meridional circulations associated with simple baroclinic waves in a two-level quasi-geostrophic model. Tellus 6, 273–286. doi:10.1111/j.2153-3490.1954.tb01123.x

- Rhines, P. B. and Bretherton, F. 1973. Topographic Rossby waves in a rough-bottomed ocean. J. Fluid Mech. 61, 583–607. doi:10.1017/S002211207300087X

- Steinsaltz, D. 1987. Instability of baroclinic waves with bottom slope. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 17, 2343–2350. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1987)017<2343:IOBWWB>2.0.CO;2