Abstract

Educating gamblers about responsible gambling (RG) practices (e.g. setting and adhering to a pre-set money limit) plays a central role in minimizing the harms associated with electronic gaming machine (EGM) play. However, little is known about when such educational information is best presented. Herein, using the principle of active learning, we tested the idea that players’ intentions to gamble responsibly will be heightened if RG educational information is provided in advance of (as opposed to following) a RG-related decision. To this end, a community sample of EGM players who were at a gaming venue (N = 98) were recruited to play an ostensibly real virtual reality slot machine and complete a survey prior to their planned gambling session. Participants were shown a RG-oriented educational animation just prior to initiating play or in advance of making a decision about whether to continue playing after their money limit was reached. As predicted, players who viewed the educational animation in advance of a RG-related decision about continuing play were more likely to express an intention to set a money limit in their upcoming gambling session at the gaming venue. Disordered gambling symptomatology moderated this effect—players low (compared to those high) in disordered gambling symptomatology expressed greater intention to set a money limit when the educational animation was viewed directly in advance of making a RG-related decision. Results suggest that learning RG actively (i.e. pairing RG education with its associated behavior, in vivo) can increase players’ intention to gamble responsibly.

Introduction

Risking money on the outcome of a chance-based game can be an exciting way to spend time (and perhaps win some money; Wulfert et al. Citation2005). Unfortunately, some players gamble excessively, which places them at a heightened risk for a range of psychological, interpersonal, and financial problems (Griffiths Citation1999; Currie et al. Citation2006). This tendency is particularly prevalent among electronic gaming machine (EGM) players (see Breen and Zimmerman Citation2002; Wiebe et al. Citation2006). As such, researchers and policy makers have emphasized the need for players to be educated about the importance of making well-informed decisions about their gambling behavior (Blaszczynski et al. Citation2004; Bernhard, Citation2007; Reith, Citation2009; Wood and Griffiths, Citation2010).

Although the ultimate decision to gamble and continue doing so in the face of mounting losses remains with the player (see Blaszczynski et al. Citation2004), most gambling operators have accepted a duty of care as evidenced by the design and implementation of an array of harm-reduction responsible gambling (RG) tools (see Smith and Wynne Citation2004; Productivity Commission Citation2010; Wohl, Sztainert, et al. Citation2013). For example, operators have made modifications to machines that allow players to set a limit on the amount of money they are willing to lose in a given session (Blaszczynski et al. Citation2004). Such limit setting RG tools have a proven track record of helping players gamble responsibly (Monaghan Citation2008; Wohl et al. Citation2014; Auer and Griffiths Citation2014b). Additionally, educational materials have been developed to stress the value of setting a money limit (see Wohl et al. Citation2010). For example, Canadian operators commissioned Wohl and colleagues (see Wohl et al., Citation2010, and, Wohl, Santesso, et al., Citation2013) to create and test the RG utility of an education-based animation that informs players about the odds of winning and the benefits of setting a money limit on gambling. Results showed that EGM players who viewed the animation prior to gambling were more likely to adhere to their money limit compared to EGM players who viewed a control video. However, no research has examined when players will benefit the most from viewing RG educational material.

Herein, we apply the technique of active learning—a form of learning in which the learner is experientially engaged in the learning process (see Revans Citation1982)—to test the idea that the intentions to gamble responsibly will be influenced by the timing of RG educational material. This idea is in accord with research in the financial literacy domain, which argues that knowledge is best conveyed via ‘just in time’ education (i.e. education should be directly paired with a particular financial decision; Fernandes et al. Citation2014; see also Hurla et al. Citation2017). Based on these ideas, we hypothesized that EGM players who are presented with RG information about the benefits of setting and adhering to a money limit ‘just in time’ (i.e. when they are about to make the decision whether or not to adhere to a money limit) will report greater intention to set a money limit in their subsequent gambling session than players who watch the animation prior to play.

Electronic gaming machines and disordered gambling

Relative to other types of gamblers, EGM players have a higher prevalence rate of disordered gambling (Wiebe et al. Citation2006; Holtgraves Citation2009) and exhibit a more rapid onset of gambling problems (Breen and Zimmerman Citation2002; Clarke et al. Citation2006). One reason for the addictive nature of EGMs is their structural characteristics (i.e. properties of a gambling apparatus or a game; Griffiths Citation1993; Dowling et al. Citation2005; Parke and Griffiths Citation2006). For example, EGMs’ payout interval and reward distribution are associated with the development of risky gambling behaviors (e.g. high rate of betting) that are difficult to extinguish (Blaszczynski and Nower Citation2002; Dowling et al. Citation2005; Leino et al. Citation2015).

Critically, EGM players often exhibit erroneous cognitions (i.e. incorrect, faulty beliefs) about the games they play on EGMs (Walker Citation1992; Sévigny and Ladouceur Citation2003). For instance, many EGM players fail to understand that previous outcomes have no bearing on subsequent outcomes (Wohl et al. Citation2010). Instead, they hold the belief that a big win is likely to follow from prolonged loss, which results in chasing behavior (i.e. persistent play in the face of financial loss) and other gambling-related harms (e.g. Bandura Citation1977; Kim et al. Citation2014; Toneatto et al. Citation1997; Walker Citation1992; Wohl et al. Citation2010; Young and Wohl Citation2009). EGM players also tend to believe that EGM outcomes sample without replacement (i.e. dependent events occur when an action removes a possible outcome, and the outcome is not replaced before a second action takes place; see Tversky and Kahneman Citation1992; Walker Citation1992). In actuality, EGMs sample with replacement (i.e. outcomes are independent, and the odds never change). A lack of understanding about how EGM outcomes are sampled is not benign. People who believe that EGM outcomes sample without replacement are apt to continue gambling despite mounting losses (Sharpe and Tarrier Citation1993)—a predictor of disordered gambling (e.g. Griffiths Citation1993; Ladouceur and Walker Citation1996; Ladouceur and Sévigny Citation2005; Wohl et al. Citation2010, Citation2013).

To reduce the risks associated with EGM play, RG tools have been developed that help the EGM player manage their gambling expenditures. The money limit tool—a program embedded in EGMs that provides players with an opportunity to set a limit on the amount of money they are willing to lose and then subsequently reminds players when their limit has been reached—has received significant attention by researchers and policy makers alike (see Ladouceur et al. Citation2012 for a review). This attention is, by-and-large, justified because the tool has demonstrated utility for minimizing excessive spending (Monaghan Citation2008; Wohl et al. Citation2014; Auer and Griffiths Citation2014a). Educational materials also have been developed to increase the perceived value of setting a money limit and facilitate both money limit setting and adherence (Williams et al. Citation2004; Responsible Gambling Council Citation2010; Wohl et al. Citation2010, Citation2014). For example, on behalf of Canadian gambling operators, Wohl et al. (Citation2013) created an education-based animation resource entitled, The Slot Machine: What Every Player Needs to Know. This 3-minute animation was designed to educate players on how EGMs function (e.g. the independence of outcomes in slot machine play or the ‘replacement feature’), the prudence of setting expenditure limits when playing, and strategies to avoid exceeding those limits. Importantly, participants who watched the educational animation before gambling demonstrated a reduction in erroneous cognitions, an increase in the belief that RG habits effectively minimize the risks of gambling, and were more likely to report staying within their pre-set money limit.

When should responsible gambling information be presented to players?

Despite the evidence demonstrating the RG utility of educational materials, there exists a significant gap in knowledge about when such materials are best presented to players. Specifically, to our knowledge, there has been no research testing whether there is an optimal time for players to learn about money limit setting and adherence that would best facilitate future RG intentions (and ideally behavior). To address this gap in the RG literature, we turned to research and theory in educational psychology as well as financial literacy.

Active learning is an instructional method that engages students in the learning process (see Revans Citation1982). In short, the core element of active learning is that simple exposure to knowledge (i.e. passive learning) from formal sources in the absence of engagement with that knowledge does not produce learning. Instead, learning occurs best when the learner is experientially engaged with the knowledge being acquired (Bonwell and Eison Citation1991). Through the process of active learning assumptions are challenged, results are confronted, and self-understanding improves, which promotes reflection about future action and increases performance over time (see Freeman et al. Citation2014).

We contend that the basic principles of active learning are applicable to RG education. In particular, RG educational material should have its greatest utility if presented when the player is engaging with a RG tool that is relevant to the knowledge being disseminated by the educational material (i.e. when a RG decision is about to be made). Practically, this would mean that players should report greater intention to gamble responsibly if education about the benefits of money limit setting and adherence was presented when players reached their limit (and must decide whether or not to continue playing) than in the absence of a RG-related decision. This is also in line with financial literacy education, which argues that the impact of financial-based education decays with time (Fernandes et al. Citation2014). In this light, Hurla et al. (Citation2017) recommended that RG information be presented ‘just in time.’ Specifically, RG information should be presented just before a player makes a RG decision to best encourage and facilitate informed decision making.

In the spirit of the recommendation offered by Hurla et al. (Citation2017) , we varied whether players received RG information ‘just in time’ or prior to initiating play. To this end, we used the 3-minute animation created by Wohl, Santesso, et al. (Citation2013) as the RG educational material and had a community sample of EGM players gamble on an ostensibly real virtual reality slot machine at two local casinos. We hypothesized that intention to gamble responsibly in their subsequent gambling session at the gaming venue would be heightened by active (compared to passive) learning—that is, when the RG educational material is presented ‘just in time’ (compared to prior to initiating play).

We also assessed whether active learning influences players’ limit adherence (i.e. the decision to quit or continue gambling on the virtual reality slot machine when their money limit was reached). We did not have an a priori hypothesis about possible between-group (i.e. active learning vs. passive learning) differences on session limit adherence. This is because, in both conditions, the virtual reality slot machine game was preprogrammed so that players experienced significant loss rapidly. Thus, they may not want to continue playing on a ‘losing machine’. Additionally, all participants were recruited prior to initiating a gambling session at the casino, and thus may not want to continue playing because they want to play in the casino (as opposed to continue playing in the virtual reality casino). To the point, players may be unwilling to continue playing beyond their limit for reasons other than when they viewed the RG educational material.

RG tools are for prevention not intervention: the moderating role of problem gambling severity

RG tools are typically geared toward the prevention of disordered gambling and not as a means to intervene once a player has developed problems (see Blaszczynski et al. Citation2004). Once a gambling disorder is established, problem gambling behaviors are difficult to reverse (Delfabbro et al. Citation2006). In this light, perhaps unsurprisingly, research that has tested the utility of RG tools to promote informed-decision making has shown that they are either ineffectual for disordered gamblers or less effective than they are for non-disordered gamblers (see Wohl et al., Citation2010, Wohl, Santesso, et al., Citation2013; Stewart and Wohl Citation2013). As such, we hypothesized that educating players about the need for limit adherence at the time a decision is being made (active learning) will likely not have the expected positive impact on RG decisions (i.e. intention to gamble responsibly in a future gambling session) among those high in disordered gambling symptomatology. Conversely, players low in disordered gambling symptomatology (i.e. non-disordered gamblers) should be more apt to understand and utilize the information conveyed in the animation and should thus be more likely to engage in RG behavior when the RG information is learned actively (compared to passively).

We also tested the possible moderating role of disordered gambling symptomatology on the relation between timing of RG educational information and limit adherence. However, akin to our hesitation to hypothesize whether the manipulation would influence limit adherence during the simulated gambling session, we were hesitant to predict moderation by disordered gambling symptomatology.

Method

Participants

A sample of 98 slot machine players (Male = 42) ranging in age from 18 to 88 years old (M = 50.25) were recruited from two local casinos (Rideau Carleton Raceway in Ottawa, Canada, n = 44; Club Regent in Winnipeg, Canada, n = 54). Participants were eligible to participate if they were at their respective casinos to play slots but had not yet gambled. The study took on average 25 minutes to complete and each participant was compensated with a $20 gift card to a nation-wide coffee shop.

Procedures

Participants were recruited upon entering the casino to participate in a study on gambling attitudes. Those who were interested were told that they would be filling out surveys and playing on a virtual reality (VR) slot machine, where they would have the opportunity to win money (in the form of a gift card). Interested participants were then shown to a conference room and placed at individual desks, where the study was explained in further detail.

Participants were told that although $20 would be uploaded into the VR slot machine, $10 would be compensation for participating in the study, and up to $10 would be theirs to gamble with. They were then asked how much of the $10 allocated to the gambling session they would like to play with. This would act as the participant’s money limit. All machines in the VR casino used 25 cent credits and were single-line machines. Participants could bet 1, 2 or 3 credits per spin. Once they decided on the amount and granted informed consent, they completed a battery of questionnaires.Footnote1

Participants were then randomly assigned to either the active learning or passive learning condition. In the active learning condition, participants were guided through the VR casino (modelled after the Rideau Carleton Raceway) and asked which slot machine (among approximately 100 machines) they wanted to play on in the casino. Once they chose a machine, the number of credits (corresponding to the dollar amount they set earlier) was entered as their limit. The participants then gambled on the preprogrammed (losing) VR slot machine until they reached their money limit. All participants viewed the same sequence of spins. Prior to deciding whether or not to continue playing past their pre-set limit, participants watched a three minute education-based animation entitled Slot machines: What every player needs to know, that explains how EGMs function (e.g. the independence of outcomes in slot machine play or the ‘replacement feature’), the prudence of setting money limits when playing, and strategies to avoid exceeding those limits (for more information, see Wohl et al. Citation2010). Immediately after viewing the animation, participants were asked verbally if they wanted to keep playing past their limit, using their participation compensation money, and also completed a short questionnaire that assessed their desire to continue gambling on the VR slot machine (with their participation money) and their intention to set a money limit in the subsequent gambling session at the local casino. However, they were not permitted to continue gambling if they chose to do so. In the passive learning condition, participants watched the educational animation prior to being exposed to the VR casino. Otherwise, the procedure was identical to that used in the active learning condition. Thereafter, all participants were debriefed and provided a $20 gift card to a coffee shop as remuneration.

Measures

Disordered gambling symptomatology

Symptoms of disordered gambling were assessed using the PGSI (Ferris and Wynne Citation2001). The scale consists of nine items (α = .95) that are anchored at 0 (never) and 3 (almost always). Participant scores were summed to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 27. This measure was treated as a continuous variable with higher scores indicating greater disordered gambling symptomatology (see Holtgraves Citation2009; MacLaren et al. Citation2015 for similar methodology).

Desire to continue gambling on the VR slot machine

Participants were asked whether they would like to continue playing on the VR slot machine with their participation money. Specifically, they were asked, ‘Now that you have played your $10 on the slot machine, would you like to use your participation money to gamble on any of the other games?’ Response options were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

Future limit setting intentions

The impact of the video on players’ intention to set limits in the future was measured using two items (r = .56) anchored at 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree). The items were: ‘The information provided during this study will make me more cautious of how much money I spend playing the slot machines in the [name of the gambling venue] today’ and ‘The information provided during this study will ensure I set a limit on the amount of money I spend playing the slot machines in the [name of the gambling venue] today’. The two items were averaged to create an index of future limit setting intentions such that higher scores reflect greater future limit setting intentions.

Results

Preliminary analyses

There were no between condition effects of age or sex, ps > .23 and thus we collapsed across these variables in the subsequent analyses. The mean for disordered gambling symptomatology was 2.47 (SD = 4.28). A total of 41 participants were categorized as no risk (43.2%), 28 were categorized as low risk (29.5%), 18 as moderate risk (18.9%) and 8 as problem gamblers (8.4%). There was not a significant difference between the average money limit set in the passive learning condition (M = 9.08) and the active learning condition (M = 8.23), t(96)= −1.91, p = .06. The mean for limit setting intentions was 4.94 (SD = 1.76), which was significantly above the mid-point of the scale, t(97) = 8.07, p < .001. There was no correlation between disordered gambling symptomatology and limit setting intentions, r = .16, p = .13.

Main analyses

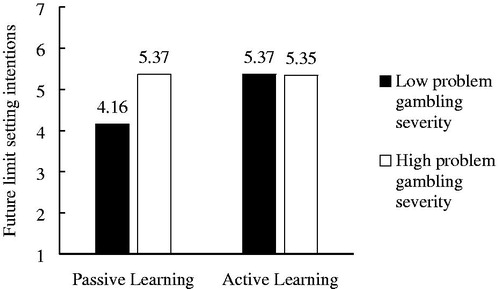

To test the possible moderating influence of disordered gambling symptomatology on the association between RG educational video timing and intention to set a money limit, the timing manipulation (coded 0 = passive learning, coded 1 = active learning) and disordered gambling symptomatology (centered), as well as their product were entered into a regression as predictors of future limit setting intentions (see ). The omnibus test of the model was significant, R2 = .11, F(3, 91) = 3.93, p = .01. There was a main effect of timing, b = .76, t = 2.17, p = .03, CI = [.06, 1.46], such that those who watched the video when they reached their money limit were more likely to endorse future limit setting (M = 5.36, SD = 1.79) than those who watched the video before gambling (M = 4.57, SD = 1.67). There was also a main effect of disordered gambling symptomatology, b = .09, t = 2.14, p = .04, CI = [.007, .18], such that those high in disordered gambling symptomatology were more likely to endorse limit setting than those low in disordered gambling symptomatology.

Figure 1. Moderating influence of disordered gambling symptomatology on the association between timing of educational animation and future limit setting intentions.

The presence of a significant interaction qualified the main effect results, b = −.18, t = −2.13, p = .04, CI = [−.35, −.01]. A moderation analysis showed that the timing of the video had a significant impact on future limit setting at 1 SD below the mean of disordered gambling symptomatology, b = 1.21, t = 2.97, p = .004, CI = [.40, 2.02] and at the mean of disordered gambling symptomatology, b = .76, t = 2.17, p = .03, CI = [.06, 1.46], but not 1 SD above the mean of disordered gambling symptomatology, b = -.02, t = −.04, p = .97, CI = [−1.03, .99].Footnote2

Exploratory analyses

We also assessed the potential moderating influence of disordered gambling symptomatology on the relationship between the timing of a RG information video and limit adherence (i.e. whether the player wanted to quit or continue playing when their money limit had been reached). A binary logistic regression was conducted with the timing manipulation (coded 0 = passive learning, 1 = active learning), disordered gambling symptomatology (centered) and their interaction term predicting limit adherence. The results from the omnibus test were not significant, χ2(3) = 1.60, p = .66. There was not a main effect of the timing manipulation, Wald’s χ2(1) = .39, p = .53, B = .38, SE = .61, OR = 1.46, CI = [.44, 4.87]. Specifically, rates of limit adherence did not differ between the passive learnng condition (86.5% adherence) and the active learning condition (84.8% adherence). The main effect of disordered gambling symptomatology, Wald’s χ2(1) = 1.14, p = .27, B = .11, SE = .10, OR = 1.11, CI = [.92, 1.35] was also not significant. Similarly, there was no interaction effect, Wald’s χ2(1) = 1.09, p = .30, B = −.15, SE = .15, OR = .86, CI = [.64, 1.14].

Discussion

To minimize the risks associated with EGM play, RG tools have been created to educate players about the importance of setting and adhering to a pre-set money limit on gambling expenditures (Ladouceur et al. Citation2012; Wohl et al. Citation2013; Blaszczynski et al. Citation2014; Kim et al. Citation2014). Yet until now, no research has examined the ideal time for players to view such RG information. The goal of the current study was to address this gap in the literature by applying knowledge from educational psychology. According to Revans (Citation1982), people learn best when education is paired with active personal experience. Put another way, the learner should be experientially engaged in the learning process. We tested this process in the domain of RG. Specifically, in a sample of community EGM players who were at a local casino to play EGMs, we tested the hypothesis that EGM players who engage in active RG learning (i.e. educational information is tied to a specific RG decision) would be more inclined to gamble responsibly in the future than when the RG education is learned passively (i.e. when RG information is untied to RG decision making). Results from the current study provided preliminary support for our general hypothesis. Participants who viewed the educational animation just prior to making a decision about whether to adhere to their pre-set money limit reported greater willingness to set and adhere to a pre-set money limit during their next gambling session (which was to take place immediately following participation in the study) compared to those who watched the animation just prior to beginning play.

The results of the current study are also in line with research on financial literacy education, which has found that the impact of financial education decays over time (for a meta-analysis see, Fernandes et al. Citation2014). According to Thompson et al. (Citation2000) this decay occurs because people find it difficult to retrieve and apply knowledge gained from education to later personal decisions. Thus, there must be an immediate opportunity to use the knowledge gained or it will decay. Such was the case in the current research. Participants who did not use the RG education information immediately were less likely to report an intention to engage in a RG behavior in an upcoming gambling session (i.e. setting a money limit) compared to participants who were able to use the knowledge gained immediately.

As predicted, we also found that disordered gambling severity moderated the relation between when the animation was viewed and limit setting intentions. The active learning condition, where RG education was paired with an RG decision, facilitated limit setting only among players low in disordered gambling symptomatology. RG tools are designed to prevent disordered gambling, not intervene when gambling has become disordered (Toneatto and Millar Citation2004; Cowlishaw et al. Citation2012). As such, RG tools tend not to be effective for disordered gamblers (see Stewart and Wohl Citation2013).

Interestingly, participants with elevated disordered gambling severity endorsed money limit setting (overall) to a greater extent than those low in disordered gambling severity. Although curious at face value, this result mimics those observed by Moore et al. (Citation2012). Specifically, they showed that 52.9% of non-disordered gamblers but over 66% of disordered gamblers reported setting a money limit. It is possible participants high in disordered gambling severity understand that they overspend, and that setting a money limit is a means to minimize the risks. However, EGM players high in disordered gambling severity are not willing or able to adhere to their money limit when it is reached, regardless of whether they set a money limit. Additionally, by virtue of their gambling frequency, disordered gamblers may be exposed to RG messaging more than recreational gamblers. Via exposure to RG messages, disordered gamblers (compared to recreational gamblers) may be more aware that it is important to set and adhere to a money limit. However, due to their disorder they either may not follow through and set a money limit, or if a limit is set, they may not adhere to that limit. Future research should directly assess these possibilities. Moreover, those low in disordered gambling severity are less likely to spend beyond that which they can afford to lose. As such, they may not see the value in setting a limit since they rarely have problems associated with gambling over-expenditure. Importantly, however, when presented with RG information at the time an RG decision is being made, they express a greater willingness to engage in RG behaviors.

An important qualifier of the current study is that timing of the educational video did not influence whether participants did or did not adhere to their pre-set money limit during play of the VR slot machine in the study. There are a few reasons for this lack of a significant effect. First, all participants were recruited from the lobby of a casino and indicated that they intended to play EGMs during their visit. As such, participants (regardless of condition) may not have wanted to continue playing on the simulated VR slot machine because they wanted to continue playing on the casino gaming floor, on real EGMs. The high level of limit adherence in both conditions speaks to this supposition. This high level of limit adherence resulted in a ceiling effect, which made it difficult to detect any effect of timing of the RG information. Second, all participants experienced rapid loss of their gambling funds during the experimental session. We programmed the VR slot machine so that participants would reach their pre-set limit quickly to reduce the time of the experimental session. However, this aspect of the procedure may have inadvertently made the VR slot machine unappealing. The net effect being a reluctance to continue playing once the participant’s pre-set money limit was reached.

Implications

The results from the current research suggest that active learning principles may have RG utility. Players may benefit from being provided RG information at the time they are deciding on their imminent gambling behavior. Having this information at hand may encourage players to make informed decisions. To the point, active learning of RG information may hold real world implications for money limit setting and adherence. Thus, we believe it would behoove gambling operators to explore the use of active learning principles within their RG initiatives.

One means to capitalize on these preliminary findings is to modify existing RG tools. That is, RG educational information could be repositioned to be shown at times when gambling decisions are being made. Aside from watching a three minute education-based animation when a money limit is reached (which may not be appealing to players), EGMs could be modified to provide targeted EGM messages to players when they are about to initiate play (i.e. RG messages about limit setting could be provided alongside querying the player about their desire to set a money limit) as well as when their limit is reached. Moreover, RG oriented information could be placed on the interface of Automated Teller Machines (ATM) that are located at or near a gambling establishment. There is a high probability that a player who is withdrawing money from an ATM in a casino is doing so to initiate play or to continue play (when money in hand has been lost). Providing RG information at this point may help players make informed decisions about how much (additional) money he or she is willing to lose. Among players who are thinking of withdrawing money to continue playing, embedding RG information into ATMs may create psychological tension about continued play, which may lead them to reconsider their withdrawal of additional funds.

Limitations

It is important to note some limitations of the current research. First, intentions to gamble responsibly are not equivalent to engaging in RG behaviors (e.g. setting and adhering to a pre-set money limit). Although players who watched the animation at the time they had to make a RG-relevant decision expressed greater intentions to set a limit in a subsequent gambling session, this does not mean these players will set a limit the next time they gamble. Second, an intention to set a money and/or time limit does not necessarily lead to setting a limit, or limit adherence should a limit be set. Although many EGM players do set a money limit, some surpass this limit (Wohl et al. Citation2010, Citation2013; Ladouceur et al. Citation2012). Many players stop their gambling session due to guilt associated with excessive loss, rather than because they reached their pre-set money limit (Wohl et al. Citation2008). A monetary limit is only useful if the player adheres to his or her limit.

While these limitations are clearly substantial, they do not disqualify the significant results of this study. Because there is a paucity of research examining the timing of RG education, this study is an important first step in the literature. Future research in this area should examine if players set a money or time limit and/or use other RG strategies (e.g. taking a within-gambling session break, especially when losing) in their gambling sessions following RG education. Furthermore, it is imperative that future research test whether players actually adhere to their money and or time limit when intending to do so. This could be assessed using modified EGMs on gaming floors, and/or with access to player account data. Lastly, it would behoove researchers to examine whether other constructs related to RG intentions and behavior (e.g. craving, dissociation) influence the potential effect of RG educational timing.

Conclusion

Setting a financial limit is central to minimizing the harms associated with gambling in general and EGM play in particular. Previous research has demonstrated that RG education is valuable for encouraging RG behaviors (see Monaghan and Blaszczynski Citation2010; Wohl et al. Citation2010, Citation2014; Auer et al. Citation2014). The results of this study suggest that the timing of RG education is important to its effectiveness in promoting limit adherence. Specifically, RG education about the importance of limit setting and adherence had the greatest impact on RG intentions when it was presented to the player at the time they were deciding whether to adhere to or exceed a pre-set money limit. This preliminary result suggests that RG-related behaviors are likely to increase should RG information be consumed at the point when players are making a decision about their gambling behavior. In this light, anchoring RG education to RG decision making may improve RG practices and thus help minimize gambling-related harms.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In the spirit of open science, readers should know that we also included items that assessed gambling motives, gambling cognitions, finically-focused self-concept, and dissociation. These items were included for exploratory purposes only.

2 The pattern of results remained unchanged when the analyses were conducted controlling for the size of the monetary limit participants set.

References

- Auer M, Griffiths MD. 2014a. An empirical investigation of theoretical loss and gambling intensity. J Gambl Stud. 30(4):879–887.

- Auer M, Griffiths MD. 2014b. Personalised feedback in the promotion of responsible gambling: a brief overview. Responsible Gambling Rev. 1:27–36.

- Auer M, Malischnig D, Griffiths M. 2014. Is’ pop-up’ messaging in online slot machine gambling effective as a responsible gambling strategy? JGI. 29:1–10.

- Bandura A. 1977. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 84(2):191–215.

- Bernhard BJ. 2007. The voices of vices: Sociological perspectives on the pathological gambling entry in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Behav Scientist. 51(1):8–32.

- Blaszczynski A, Gainsbury S, Karlov L. 2014. Blue Gum gaming machine: an evaluation of responsible gambling features. J Gambl Stud. 30(3):697–712.

- Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Shaffer HJ. 2004. A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. J Gambl Stud. 20(3):301–317.

- Blaszczynski A, Nower L. 2002. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 97(5):487–499.

- Bonwell C, Eison J. 1991. Active learning: creating excitement in the classroom AEHE-ERIC higher education report No. 1. Washington, D.C.: Jossey-Bass.

- Breen RB, Zimmerman M. 2002. Rapid onset of pathological gambling in machine gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 18(1):31–43.

- Clarke D, Tse S, Abbott M, Townsend S, Kingi P, Manaia W. 2006. Key indicators of the transition from social to problem gambling. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 4(3):247–264.

- Cowlishaw S, Merkouris S, Dowling N, Anderson C, Jackson A, Thomas S. 2012. Psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11: CD008937.

- Currie SR, Hodgins DC, Wang J, El-Guebaly N, Wynne H, Chen S. 2006. Risk of harm among gamblers in the general population as a function of level of participation in gambling activities. Addiction. 101(4):570–580.

- Delfabbro P, Lahn J, Grabosky P. 2006. It’s not what you know, but how you use it: statistical knowledge and adolescent problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. 22(2):179–193.

- Dowling N, Smith D, Thomas T. 2005. Electronic gaming machines: are they the 'crack-cocaine' of gambling? Addiction. 100(1):33–45.

- Fernandes D, Lynch JG, Netemeyer RG. 2014. Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Manage Sci. 60(8):1861–1883.

- Ferris J, Wynne H. 2001. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: user manual. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

- Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, Smith MK, Okoroafor N, Jordt H, Wenderoth MP. 2014. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 111(23):8410–8415.

- Griffiths M. 1993. Fruit machine gambling: the importance of structural characteristics. J Gambl Stud. 9(2):101–120.

- Griffiths M. 1999. Gambling technologies: prospects for problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. 15(3):265–283.

- Holtgraves T. 2009. Gambling, gambling activities, and problem gambling. Psychol Addict Behav. 23(2):295–302.

- Hurla R, Kim M, Singer E, Soman D. 2017. Applying findings from financial literacy to encourage responsible gambling. Behavioural economics in action at Rotman (BEAR) report series. [accessed 2018 Oct 20]. Toronto. http://www.rotman.utoronto.ca/bear.

- Kim HS, Wohl MJA, Stewart MJ, Sztainert T, Gainsbury SM. 2014. Limit your time, gamble responsibly: setting a time limit (via pop-up message) on an electronic gaming machine reduces time on device. Int Gambl Stud. 14(2):266–278.

- Ladouceur R, Blaszczynski A, Lalande DR. 2012. Pre-commitment in gambling: a review of the empirical evidence. Int Gambl Stud. 12(2):215–230.

- Ladouceur R, Sévigny S. 2005. Structural characteristics of video lotteries: effects of a stopping device on illusion of control and gambling persistence. J Gambl Stud. 21(2):117–131.

- Ladouceur R, Walker M. 1996. A cognitive perspective on gambling. In: Salkovskies PM, editor. Trends in cognitive and behavioural therapies. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; p. 89–120.

- Leino T, Torsheim T, Blaszczynski A, Griffiths M, Mentzoni R, Pallesen S, Molde H. 2015. The relationship between structural game characteristics and gambling behavior: a population-level study. J Gambl Stud. 31(4):1297–1315.

- MacLaren V, Ellery M, Knoll T. 2015. Personality, gambling motives and cognitive distortions in electronic gambling machine players. Personal Individual Differ. 73:24–28.

- Moore SM, Thomas AC, Kyrios M, Bates G. 2012. The self-regulation of gambling. J Gambl Stud. 28(3):405–420.

- Monaghan S. 2008. Review of pop-up messages on electronic gaming machines as a proposed responsible gambling strategy. Int J Ment Health Addict. 6(2):214–222.

- Monaghan S, Blaszczynski A. 2010. Impact of mode of display and message content of responsible gambling signs for electronic gaming machines on regular gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 26(1):67–88.

- Parke J, Griffiths M. 2006. The psychology of the fruit machine: the role of structural characteristics (revisited). Int J Ment Health Addict. 4(2):151–179.

- Productivity Commission. 2010. Gambling, Report no. 50, Canberra.

- Reith G. 2009. Living with risk: chance, luck, and the creation of meaning in uncertainty. In: Welchman J, editor. The aesthetics of risk. Zurich: JRP Ringier; p. 57–58.

- Responsible Gambling Council. 2010. Insight 2010: informed decision making. [accesses 2018 Oct 25]. http://www.responsiblegambling.org/rg-news-research/rgc-centre/insight-projects/docs/default-source/research-reports/informed-decision-making.

- Revans RW. 1982. The origins and growth of action learning. Bromley, UK: Chartwell-Bratt

- Sévigny S, Ladouceur R. 2003. Gamblers’ irrational thinking about chance events: the ‘double switching’ concept. Int Gambl Stud. 3:149–161.

- Sharpe L, Tarrier N. 1993. Towards a cognitive-behavioural theory of problem gambling. Br J Psychiatry. 162:407–412.

- Smith GJ, Wynne HJ. 2004. VLT gambling in Alberta: a preliminary analysis. Edmonton, Alberta: Alberta Gaming Research Institute.

- Stewart MJ, Wohl MJ. 2013. Pop-up messages, dissociation, and craving: how monetary limit reminders facilitate adherence in a session of slot machine gambling. Psychol Addict Behav. 27(1):268–273.

- Thompson L, Gentner D, Loewenstein J. 2000. Avoiding missed opportunities in managerial life: analogical training more powerful than individual case training. Organizational Behav Hum Decision Process. 82(1):60–75.

- Toneatto T, Blitz-Miller T, Calderwood K, Dragonetti R, Tsanos A. 1997. Cognitive distortions in heavy gambling. J Gambl Stud. 13(3):253–266.

- Toneatto T, Millar G. 2004. Assessing and treating problem gambling: empirical status and promising trends. Can J Psychiatry. 49(8):517–525.

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. 1992. Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J Risk Uncertain. 5(4):297–323.

- Walker MB. 1992. The psychology of gambling. Elmsford (NY): Pergamon Press.

- Wiebe J, Mun P, Kauffman N. 2006. Gambling and problem gambling in Ontario 2005. Toronto, Ontario: Responsible Gaming Council.

- Williams RJ, Connolly D, Wood R, Currie S, Davis R. 2004. Program findings that inform curriculum development for the prevention of problem gambling. Gambl Res. 16:47–69.

- Wohl MJA, Christie K, Matheson K, Anisman H. 2010. Animation-based education as a gambling prevention tool: correcting erroneous cognitions and reducing the frequency of exceeding limits among slots players. J Gambl Stud. 26(3):469–486.

- Wohl MJ, Kim HS, Sztainert T. 2014. From the laboratory to the casino: using psychological principles to design better responsible gambling tools. Respons Gambl Rev. 1:16–26.

- Wohl MJ, Lyon M, Donnelly CL, Young MM, Matheson K, Anisman H. 2008. Episodic cessation of gambling: a numerically aided phenomenological assessment of why gamblers stop playing in a given session. Int Gambl Stud. 8(3):249–263.

- Wohl MJA, Santesso DL, Harrigan K. 2013. Reducing erroneous cognition and the frequency of exceeding limits among slots players: a short (3-minute) educational animation facilitates responsible gambling. Int J Ment Health Addict. 11(4):409–423.

- Wohl MJ, Sztainert T, Young MM. 2013. The CARE model: how to improve industry–government–health care provider linkages. In: Richard DCS, Blaszczynski A, Nower, L, editors. The Wiley‐Blackwell Handbook of Disordered Gambling. New York: Wiley; p. 263–282.

- Wood RTA, Griffiths MD. 2010. Social responsibility in online gambling: voluntary limit setting. World Online Gambl Law Rep. 9:10–11.

- Wulfert E, Roland BD, Hartley J, Wang N, Franco C. 2005. Heart rate arousal and excitement in gambling: winners versus losers. Psychol Addict Behav. 19(3):311–316.

- Young MM, Wohl MJ. 2009. The Gambling Craving Scale: psychometric validation and behavioral outcomes. Psychol Addict Behav. 23(3):512–522.