Abstract

Introduction

Besides supply reduction, preventive interventions to reduce harm from gambling include interventions for the reduction of demand and to limit negative consequences. Several interventions are available for gamblers, e.g. limit-setting. Reviews have been published examining the evidence for specific measures as well as evaluating the effect of different measures at an overall level. Only a few of these have used a systematic approach for their literature review. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is twofold. First, to assess the certainty of evidence of different preventive measures in the field of educational programs and consumer protection measures, including both land-based and online gambling. The second is to present shortcomings in eligible studies to highlight what type of information is needed in future studies.

Method

This systematic review included measures administered in both real-life settings and online. Twenty-eight studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria and had low or moderate risk of bias.

Results

The results showed that only two measures (long term educational programs and personalized feed-back) had an impact on gambling behavior. Follow-up period was short, and measures did not include gambling as a problem. The certainty in most outcomes, according to GRADE, was very low. Several shortcomings were found in the studies.

Discussion

We concluded that the support for preventive measures is low and that a consensus statement regarding execution and methods to collect and analyze data for preventive gambling research is needed. Our review can serve as a starting point for future responsible gambling reviews since it evaluated certainty of evidence.

Introduction

Perspectives on harm and prevention in gambling

Gambling activities can be classified as nonproblematic, at-risk, or problematic with progressively increasing harm. Problem gambling is regarded as a public health issue (Abbott et al. Citation2018) and its harmful consequences have been researched extensively in clinical and epidemiological studies (Lorains et al. Citation2011; Dowling et al. Citation2015). Langham et al. (Citation2015) conceptualized seven dimensions of harm emanating from gambling: financial harm, relationship disruptions, emotional or psychological distress, decrements to health, cultural harm, reduced performance at work or in academic study, and likelihood of criminal activity. Moreover, recent studies have found that even low-level gambling can result in some form of harm (Raisamo et al. Citation2015; Canale et al. Citation2016).

Preventive measures serve as one solution to decrease the likelihood of gambling-related harm. The fact that both high-risk and low-risk gambling can result in some form of harm substantiates the need for preventive measures. Therefore, there is a significant need to better understand methods which can prevent problematic gambling and how gambling-related harms can be limited. Understanding of preventive measures is becoming increasingly important due to increases in the incidence and scope of Internet gambling, which has resulted in gambling activities being permanently available in the home or on a smart phone (Abbott et al. Citation2018).

Currently, preventive interventions aimed at reducing the incidence of gambling, particularly problematic gambling, include demand reduction, harm reduction, and supply reduction. Demand reduction refers to interventions that reduce the demand for the availability of gambling activities through affecting changes in individuals’ knowledge concerning gambling, the harms related to gambling, personal motivation to gamble, or the social context in which gambling takes place. Examples of demand reduction include both universal and targeted programs directed at the youth and/or individuals with gambling addiction (Ladouceur et al. Citation2013; Keen et al. Citation2017).

Harm reduction refers to consumer protection measures, such as responsible gambling (RG). These measures are defined as policies and practices intended to reduce the potential harms resulting from gambling and are traditionally implemented by the gambling industry (Blaszczynski et al. Citation2004, Citation2008, Citation2011). Common features of RG measures include setting limits on the amount of time or money individuals can spend gambling and supplying personal feedback on gambling activities or self-exclusion (Ivanova et al. Citation2019). Williams et al. (Citation2012, p. 6) stated the following regarding RG measures: ‘Unfortunately, the development, implementation, and evaluation of most of these initiatives have been a haphazard process. Most have been put in place because they ‘seemed like good ideas’ and/or were being used in other jurisdictions, rather than having demonstrated scientific efficacy or being derived from a good understanding of effective practices in prevention.’ This paradigm has been criticized for lacking consideration of the vulnerability of individuals who gamble and the need for gambling companies to take a more proactive stance to prevent problematic gambling (Hancock and Smith Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

Due to the criticisms of RG measures, researchers have called for a new consumer protection paradigm that prioritizes the duty of care of gambling operators, the integrity of operations, and consumer protection based on online and real-world preventive measures. Such preventive measures include setting limits on gambling activities or excluding individuals from gambling sites (Hancock and Smith Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Furthermore, some argue for preventive measures to take place in conjunction with a public health approach in terms of the regulation of gambling and the development of policies. In this review, we interpret RG from a consumer protection paradigm as a method of limiting harm resulting from gambling by assisting individuals engaging with gambling products to avoid potential gambling-related harms.

Another gambling-related harm preventive measure is supply reduction. This method has been evaluated in two recent systematic reviews (Meyer et al. Citation2018; McMahon et al. Citation2019). Both reviews state that there is a lack of research concerning supply reduction measures. Meyer et al. (Citation2018) reported some inconsistences in the findings concerning supply reduction as a gambling-prevention measure. Nonetheless, the researchers stated that a reduction in the supply of gambling products/activities resulted in a decline in gambling participation, a reduced number of frequent gamblers, lower demand for therapy due to problematic gambling, and fewer problematic gambling cases. This claim is congruent with findings that suggest that supply reduction is the most effective preventative measure in reducing other problematic behaviors, such as alcohol consumption and tobacco use (Babor et al. Citation2010). Studies investigating the reduction of gambling supply are not included in our review since there is a need to limit the aim and scope of the study, and because existent research is very recent (Meyer et al. Citation2018; McMahon et al. Citation2019).

Reviews and meta-analysis focusing on preventive measures in gambling

An umbrella review focusing on preventive measures in gambling reported the publication of ten systematic reviews comprising 55 unique primary studies (McMahon et al. Citation2019). Most of the systematic reviews reported on studies of interventions aimed at harm reduction and focused specific preventive measures, such as limit-setting or interventions incorporated into the design of gambling activities (e.g. pop-messages). Support for most of the preventive measures considered was weak and the general conclusion drawn was that the studies concerning RG measures reported the absence of a significant effect in terms of decreasing gambling-related harm (McMahon et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, the reviews lacked scientific rigor. Only one out of the ten systematic reviews assessed the risk of bias in the primary studies examined and took bias into account when evaluating the effects of preventive measures on gambling. None of the studies used GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) (Guyatt et al. Citation2011) or other methods of assessing the reliability and validity of the evidence. Another review indicated a need for further research in this area and increased methodological rigor in research through the use of specific guidelines when evaluating the effects of different preventive measures (Ladouceur et al. Citation2017). Two significant aspects emanating from the review are a lack of repeated measures methods and the use of different measures of gambling (Ladouceur et al. Citation2017). These two aspects may be the primary reasons for the lack of significant results.

Apart from the need for systematic reviews and meta-analyses that examine different types of preventive measures in gambling (e.g. educational programs and RG measures), there is also a need to address the shortcomings of existing research when discussing the different aspects of the study’s methods and how the results were reported. These shortcomings have resulted in the exclusion of studies in review papers and unclear results that are challenging to interpret.

Aim of this study

The aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis were two-fold. First, in the framework of a systematic review, we assessed the certainty of the evidence relating to different gambling preventive measures in the context of educational programs and consumer protection measures (e.g. responsible measures for both real-world and online gambling). Second, our goal was to present and discuss the shortcomings identified in eligible studies to better understand how preventive measures should be designed and tentatively identify the probable results of future studies.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al. Citation2009).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the educational programs are presented in . The criteria for RG strategies are presented in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for gambling prevention/educational programs.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for responsible gambling strategies.

Literature search and databases

We conducted a literature search in the following databases: PsycINFO (EBSCO), PubMed (NLM), Scopus (Elsevier), and SocINDEX (EBSCO). Search strategies consisted of a combination of free text terms and controlled vocabulary. In addition, a simultaneous centralized search of multiple EBSCO databases was conducted. Databases included were: Academic Search Elite, CINAHL, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and SocINDEX. All databases were searched for studies that were published from January 2000 to October 2018. Peer reviewed articles in English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish were included. The reference lists presented in the reviews and identified studies were manually searched. Search strategies were developed by an information specialist in collaboration with the experts in the review team. Search strategies according to PRISMA are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Selection of studies

Two experienced reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full text articles if either or both reviewers considered a study to be potentially eligible. For potentially eligible studies, both reviewers read the full texts and consensus was reached. In cases of disagreement, the project group discussed the article(s) and consensus was reached. Supplementary Material 2 lists the excluded articles and the reasons for exclusion.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two reviewers (experienced gambling researchers) independently assessed each eligible study for risk of bias, followed by discussions in the project group (by authors DF, JS, JO, and AP) until consensus regarding inclusion was reached. For randomized studies and nonrandomized controlled studies (NRSI), we used the Rob 2.0 checklist (Higgins et al. Citation2016). For NRSI, we listed the critical confounders: gender, age, gambling problem, and/or overall gambling behavior. These confounders were selected since it is established that gambling, gambling behaviors, and gambling problems (as outcome variables) differ with regard to age and gender (Merkouris et al. Citation2016). The confounds age and gender have also been used to assess bias in non-randomized studies of gambling interventions (Sterne et al. Citation2016). If the confounders were not reported in the selected study, or if it was not clearly stated how these were handled, the risk of bias was assessed as critical and no further domains were evaluated.

The first domain of the Rob 2.0 checklist, selection bias was replaced with the following: Were the groups, at baseline, similar in terms of important confounders? If not, were adjustment techniques used to attempt to correct the selection biases?

We developed a checklist for studies lacking control groups (see Supplementary Material 3). Only studies with low or moderate risk of bias were included in the analyses. Excluded studies with high risk of bias are listed in Supplementary Material 4. The characteristics of the studies included in this review are listed in Supplementary Material 5.

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis was carried out using the Review Manager version 5.3. (Citation2015), with the random effects model due to clinical heterogeneity in the studies. For dichotomous outcomes, the risk difference (RD) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method (Kuritz et al. Citation1988). For continuous outcome variables, the mean difference (MD) or standard mean difference (SMD) with a 95% CI was calculated using the Inverse Variance method. In one case, we contacted the authors of the relevant studies and requested supplementary data from Canale et al. (Citation2016). Examination of this data qualified the study for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Educational programs were divided into two groups: short (programs taking place on one occasion) and long (programs taking place over several occasions, usually between four and six sessions) interventions. Subsequent analyses were based on these two groups. To merge data into the meta-analysis, the interventions had to be comparable in intensity and length. Therefore, occasional sessions were not comparable to programs lasting several weeks.

The certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence was assessed with the GRADE (strong (⊕⊕⊕⊕), moderate (⊕⊕⊕Ο), low (⊕⊕ΟΟ), or very low (⊕ΟΟΟ)) (Guyatt et al. Citation2008). We applied the following rules in this systematic review:

Education programs with a follow-up time of less than or equal to 6 months; indirectness –1.

If an intervention was evaluated in only one smaller study (<350 participants) and the outcome was not statistically significant, the certainty of the evidence was assessed as very low (⊕ΟΟΟ) (Guyatt et al. Citation2011).

When using descriptive or narrative analysis for several studies covering one intervention (since meta-analysis was not feasible due to lack of data), and the results were not statistically significant in the individual studies, the precision was −1.

If an intervention was evaluated in only one study and published for ≥10 years: indirectness −1.

The outcomes ‘knowledge’ and ‘attitudes’ are indirect measures: indirectness −1.

Results

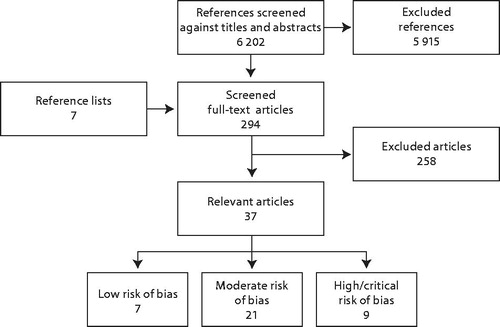

Search results and flow charts

The literature search yielded a total of 6202 records. We excluded 5915 records based on citation and abstract screening. Thus, 294 full-text articles were further assessed for eligibility. Finally, a total of 37 articles were classified as relevant and eligible based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

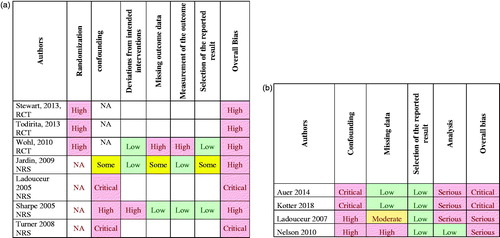

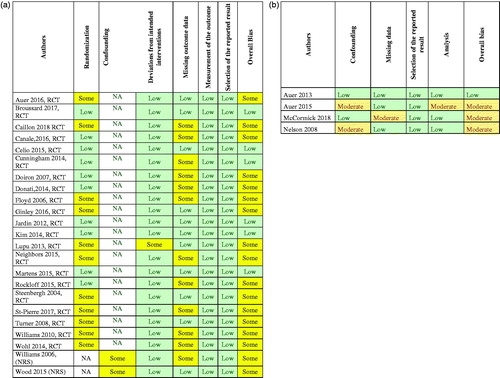

Of the 37 studies, 28 had low or moderate risk of bias (). The remaining nine studies presented with critical and high risk of bias and were not included in the analysis (Ladouceur et al. Citation2005, Citation2007; Turner et al. Citation2008; Jardin and Wulfert Citation2009; Nelson et al. Citation2010; Wohl et al. Citation2010; Stewart and Wohl Citation2013; Auer et al. Citation2014; Kotter et al. Citation2018). The shortcomings in the eligible studies are presented in the section below supplemented by outlining the risk of bias and subsequent exclusion.

Educational programs

In total, 11 studies concerning educational programs were identified as eligible (Ladouceur et al. Citation2005; Williams and Connolly Citation2006; Doiron and Nicki Citation2007; Turner et al. Citation2008; Citation2008; Williams et al. Citation2010; Wohl et al. Citation2010; Lupu and Lupu Citation2013; Donati et al. Citation2014; Canale et al. Citation2016; St-Pierre et al. Citation2017). Of these, three were excluded from the analysis due to critical or high risk for bias (Ladouceur et al. Citation2005; Turner et al. Citation2008; Wohl et al. Citation2010). The determining reasons for the classification of critical or high risk of bias in these studies were:

no information reported concerning participants’ age and sex (one study contained students that were 10 years of age);

no information regarding gambling behaviors;

unclear randomization processes; and

lack of description of attrition rates.

Of the eight remaining studies, six were conducted in school environments (Turner et al. Citation2008; Williams et al. Citation2010; Lupu and Lupu Citation2013; Donati et al. Citation2014; Canale et al. Citation2016; St-Pierre et al. Citation2017). Long-term designs were used in five studies (Turner et al. Citation2008; Williams et al. Citation2010; Lupu and Lupu Citation2013; Canale et al. Citation2016; St-Pierre et al. Citation2017). One study was conducted using college students (Williams and Connolly Citation2006) and one targeted gamblers (Doiron and Nicki Citation2007). A summary of the studies is presented in and the characteristics of the respective studies are shown in Supplementary Material 5.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies with low or moderate risk of bias regarding educational program strategies.

A meta-analysis of the identified literature was only possible for school programs with long-term interventions (spanning several weeks) and for the outcome frequency of gambling. In terms of outcome frequency, gambling had a positive decrease in frequency measured in days, SMD = 0.29 (95%CI −0.48, −0.11). The certainty of evidence was low in this case (). For the remaining outcomes, including amount of money spent on gambling, attitudes toward gambling, and knowledge (Turner et al. Citation2008; Williams et al. Citation2010; Lupu and Lupu Citation2013), the certainty of the evidence was very low (). This was also the case for educational programs aimed toward high school students (Williams and Connolly Citation2006) and interventions targeting gamblers (Doiron and Nicki Citation2007). The certainty of the evidence for the separate outcomes is shown in and .

Table 4. Summary of finding for educational program (long) compared to no intervention.

Table 5. Summary of findings for educational program (short) compared to no intervention.

None of the selected studies evaluated the effects of educational programs for staff in gambling environments on individuals who gamble.

Responsible gambling measures

The review identified 26 publications which fulfilled the inclusion criteria (). Of these, 14 were randomized controlled trials (RCT) (Steenbergh et al. Citation2004; Floyd et al. Citation2006; Cunningham et al. Citation2012; Jardin and Wulfert Citation2012; Celio and Lisman Citation2014; Kim et al. Citation2014; Wohl et al. Citation2014; Martens et al. Citation2015; Neighbors et al. Citation2015; Rockloff et al. Citation2015; Auer and Griffiths Citation2016; Ginley et al. Citation2016; Broussard and Wulfert Citation2017; Caillon et al. Citation2019), two were non-randomized studies (NRS) with control groups (Sharpe et al. Citation2005; Wood and Wohl Citation2015) and four studies did not have a comparison group (cohort studies) (Nelson et al. Citation2008; Auer and Griffiths Citation2013, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; McCormick et al. Citation2018). A summary of these studies is shown in and their characteristics are shown in Supplementary Material 5.

Table 6. Characteristics of studies with low or moderate risk of bias regarding consumer protection interventions.

Meta-analyses were possible for two RG measures: personal feedback (PF) and pop-up messaging (Supplementary Material 6). The meta-analyses for PF demonstrated that the measure results in a decrease in gambling frequency at three months. However, the certainty of the evidence was low () and the long-term effects are unknown. For the remaining RG measures and their outcomes, the certainty of evidence was very low (see ).

Table 7. Summary of finding for PFN compared to no intervention.

Table 8. Summary of finding: pop-up message.

Table 9. Summary of finding of pop up message: limitation in time or money as compared to control group/standard message.

Table 10. Summary of findings of Limitation in time or money, as compared to no intervention.

Table 11. Summary of findings for self-exclusion (short or long).

Shortcomings in the eligible studies

Studies with high or critical risk of bias

The studies with high or critical risk of bias lacked required information in several different domains () and were, therefore, excluded from the systematic review. The primary reasons for high or critical risk of bias were: (1) a lack of information concerning randomization of groups resulting in risk of confounding factors in NRS and cohort studies; (2) a lack of outcome data and information concerning the specific measurement of the effect; (3) the applied intervention deviated from the intended interventions resulting in a high risk for bias (Sharpe et al. Citation2005); and (4) flaws in terms of data analysis and presentation.

Studies with low or moderate risk of bias

Very few studies had a low risk for bias, primarily due to a lack of information regarding randomization and methodology (how and on what basis was the study done), including the absence of descriptive information on how the randomization process was carried out. Missing data was a prevalent factor in several cases (). For NRS, risk for bias was related to a lack of information regarding confounding issues (). Additional shortcomings were the use of several different outcome measurements, evaluation or presentation of the results, and different lengths of time between follow-ups. This resulted in an inability to perform meta-analysis and thus, an inability to assess progress in the program. The most pervasive shortcoming across studies was missing outcome data. In several cases, means, standard deviations, and attrition rates were not reported. These factors resulted in an inability to perform a meta-analysis on these studies and, thus, an overall analysis of the effects of different RG measures was not possible. Studies with low and moderate risk for bias were included in the systematic review.

Discussion

Despite the availability of a relatively large number of review studies in the field of prevention of gambling problems (e.g. Williams et al. Citation2012; Ladouceur et al. Citation2013; Motka et al. Citation2018), to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that assesses the certainty of evidence in a structured manner. We present the shortcomings evident in the reviewed studies on preventive education programs and RG measures. Our findings suggest that there is a low level of certainty of evidence for studies making use of long-term school interventions and PF, indicating a potential effect of these interventions. It is important to note that, in these cases, the follow-up period was short. For the remaining interventions and their outcomes, the certainty of evidence was very low. In such cases, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions concerning the effects of the intervention (i.e. whether it reduces or increases gambling or harm from gambling).

The absence of evidence across measures and studies does not imply that the intervention is not effective (Alderson Citation2004). Our inability to draw conclusions regarding the effects of the RG measures and educational programs does not necessarily suggest that the interventions had no effects. Rather, there were insufficient eligible studies to positively or negatively evaluate the effects. Thus, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence (Alderson Citation2004). This distinction is important for future systematic reviews of consumer protection measures, including RG tools and educational programs designed to diminish gambling-related harm.

One explanation for the absence of effects of interventions is that prevention measures curtail a progressive gambling trajectory. Continuation of the trajectory would cause the gambler lose increasing amounts of money over time and result in increased risk of harm. The effect of some measures might be the halting of a maladaptive gambling pattern without decreasing the amount of money or time spent gambling. Rather, the monetary and time metrics remain static, but the preventive measures diminish the progression of the problem.

A comparison to previous systematic reviews

Despite differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria, assessment of risk of bias, and certainty in evidence, our conclusion regarding the need for increased and higher-quality research is similar to that of McMahon et al. (Citation2019). Almost all previous reviews on this topic have implemented more liberal inclusion criteria than ours. For example, in our review, studies that did not report results in the form of an estimate with confidence intervals were excluded if it was not possible to calculate the result based on data presented.

Our systematic review revealed two primary results. Firstly, there appears to be a reduction in gambling consequent to an educational program and PF. These two interventions had an impact on gambling behavior, but not in terms of loss of money due to gambling. In these cases, the levels of certainty were low. Another systematic review suggested that PF is effective (Marchica and Derevensky Citation2016). However, an important point to note is the question of whether our results present with practical implications since they were not accompanied by a reduction in monetary losses. Moreover, we are currently unaware of the effects of these interventions on problem gambling or harm due to gambling. Another problem prevalent in this study was that some educational program studies did not measure gambling problems. This lack of data makes drawing inferences regarding reduction of harm in gambling prevention challenging.

The follow-up period for the studies on school-based interventions was short (up to 6 months). Therefore, the long-term effect of these interventions is difficult to determine or estimate. Our finding that educational programs may reduce gambling behaviors among students is congruent with findings in a review by Keen et al. (Citation2017) which stated that five out of nine studies reviewed reported a significant effect of educational programs on gambling behaviors. All of Keen et al.’s (Citation2017) reviewed studies (n = 9) reported an effect of the intervention on cognition or knowledge. However, this review, as in other systematic reviews on school-based interventions, did not include meta-analyses (Keen et al. Citation2017; Oh et al. Citation2017).

All the reviews considered stressed the methodological flaws present in their included studies. Ladouceur et al. (Citation2017) used an a priori approach in their review to evaluate the effects present within the factors of self-exclusion, limit-setting, training of venue employees, RG, specific game features, and behavioral characteristics of RG. They included all studies that conducted in a real-world gambling environment (excluding online gambling) and fulfilled at least one of the following criteria: (1) existence of control groups; (2) repeated measures designs; or (3) validated measurement scales. Of the 29 eligible studies, only six fulfilled all three criteria, indicating a lack of scientific rigor.

Shortcomings in the reviewed studies

Despite meeting the inclusion criteria, several flaws were present in the reviewed studies: weakness in, or lack of, reliable data, including the measurement issues; small numbers of participants; and brief follow-up periods. Furthermore, there was a lack of studies in general.

In several previous reviews, it was not possible to perform meta-analysis, which makes drawing conclusions regarding the suitable types of prevention for excessive gambling difficult. Moreover, most reviews did not attempt to conduct a meta-analysis, although some examined bias according to the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, Citation2008). In these cases, the studies concluded that the global rating would be considered weak and, therefore, study quality could not be systematically evaluated. In McMahon et al’s (2019) study, only 1 out of 10 systematic reviews assessed the risk of bias of the included primary studies and took this into account when evaluating the effects of interventions. In our review, we excluded studies with high risk of bias from the analysis because the results may be unreliable.

Overall, it is difficult to determine the effect measures or programs in the field of RG. Apart from the shortcomings mentioned earlier in the review, there are a multitude of factors that need to be assessed when considering these effects. These include risk level for the gambler, whether online gambling is prevalent or land-based venues are used (or both), and what type of gambling activity the individual engages in (specific or several activity types). Use of the interventions is also an important factor; e.g. there is low use among gamblers who have engaged with the RG tool ‘Playscan’ (Forsström et al. Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2020). There are also several demographic factors to incorporate into analyses as they are known to influence outcomes of interventions, including age and gender. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of gender in the study of gambling and problematic gambling (Merkouris et al. Citation2016). Across the studies included in the systematic reviews, very few sub-group analyses were carried out, or the results presented the analyzed effects for men and women separately. This should be addressed in future research (Romild et al. Citation2016). It is also necessary to investigate if RG measures operate in a different manner for vulnerable groups, such as people at economic disadvantage (low socio-economic status) or persons with neuropsychiatric disorders.

Another important consideration is the setting/context where the study takes place. Ladouceur et al. (Citation2017) argued that only studies in real-world gambling settings provide useful information and, therefore, used this as an a priori inclusion criteria. However, although there is a definitive need for more studies in real-world settings and there are shortcomings inherent in laboratory-based research, there are also potential benefits associated with laboratory research, such as the possibility of providing the researchers with a greater level of control. This would make it possible to examine specific factors and replicate research.

Toward a consensus in gambling prevention research

There is a framework for reporting outcomes in gambling treatment research (Walker et al. Citation2006). The framework signifies a starting point for treatment outcome studies, providing a rationale for research and making it possible to compare the effects of the treatment of gambling disorders. Preventive measures for gambling are diverse and this could partly explain the lack of definitive results and conclusions emanating from the systematic reviews. It is possible that the lack of consensus on basic measurement issues could be avoided by coming to an agreement regarding guidelines which would support the process of building evidence. Ladouceur et al. (Citation2017) recently attempted to establish guidelines for gambling-prevention research by using an a priori approach. However, including studies that fulfill at least one of the three stated criteria is problematic when conducting meta-analyses.

The process of developing research on gambling prevention requires collaboration and census concerning standards of studies. Factors to consider include what outcome measure to use and an established follow-up period. Additionally, very few sub-group analyses are carried out, at least based on the studies included in our systematic review. Most of the studies used risk as a grouping variable, but there is a need for further research in the field based on gender and type of gambling activity. One plausible hypothesis is that RG measures will be used differently, and have different effects, for sub-samples of individuals that gamble. If this is the case, the discourse established in reviews stating that there is an absence of effectiveness potentially maintains the status quo regarding preventive measures and suggests that new studies will not provide additional, valuable information since they are likely to use the same short follow-up periods or different outcome measures. Williams et al.’s (Citation2012) statement clearly depicts the state of the prevalent discourse in gambling prevention. Our systematic review drew similar conclusions, despite using the PRISMA guidelines: the empirical support for gambling preventive measures is weak and there is a need for an increased number of studies, higher-quality research, and expanding on the discourses surrounding these measures.

Limitations of this study

There are several limitations to this review study. The bias ratings were performed and matched. However, interrater reliability was not checked. Therefore, the raters may have investigated bias in the studies using different standards, thereby compromising the accuracy of the review. In such a case, studies might have been excluded or included on the wrong premises. However, the risk of bias for all articles was independently assessed by the same two researchers, followed by discussions within the project group until consensus was reached. There were few instances of disagreement between the two reviewers and consensus was reached in all the cases without significant debate or deviation.

Future research

Researchers have suggested that RG measures need to be more proactive (Hancock and Smith Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Jonsson et al. (Citation2019) investigated the use of behavioral feedback via telephone aimed at excessive gamblers. Gamblers that received feedback via telephone had a 29% decrease in theoretical losses compared to 3% for the control group. This result was obtained at a 12-week follow-up (this study was published after the literature search for our review was performed). These findings indicate that further research involving proactive measures is required.

Future efforts in the study of gambling should focus on developing a consensus statement similar to that concerning the treatment of pathological gambling/gambling disorders (Walker et al. Citation2006). Ladouceur et al. (Citation2017) also state that gambling prevention research must be theory driven. Hence, future studies should attempt to build on the existent theory and literature to find optimal methods of facilitating gambling-related behavioral change.

Using the existing frameworks on criteria for efficacy and effectiveness in prevention and public health interventions, such as the framework from the Society for Prevention Research, could be a useful first step in enhancing the quality of research. The objective of these standards is to articulate a set of principles to identify prevention programs and policies that are empirically validated and merit being labeled as ‘tested and efficacious.’ However, an important distinction to consider is the difference between efficacy and effectiveness. Effectiveness refers to the program effects when delivered under real-world conditions. To claim effectiveness, studies must meet all the conditions of efficacy trials as well as fulfilling the following criteria: program definitions, such as manuals and technical support, should be present; and theory and real-world conditions should be accounted for.

Conclusions

This systematic review showed that there is little support for RG measures and educational programs for gambling in the studies which met the inclusion criteria. Most interventions had a very low certainty of evidence. This review could serve as a model for developing educational programs and RG reviews as it evaluated the certainty of evidence and provided a systematic evaluation of the included studies. Nonetheless, more research is required to understand whether existing interventions are effective. Furthermore, consensus on the best method to conduct preventive gambling studies is required to effectively compare studies and perform meta-analyses. This is essential to further develop guidelines for the prevention of gambling-related harms and to inform gamblers and gambling companies of the presence of effective preventive measures.

Supplementary_6_Meta-analysis_.pdf

Download PDF (131.9 KB)Supplementary_5_Characteristics_of_included_studies.pdf

Download PDF (390.2 KB)Supplementary_4_Studies_with_high_risk_of_bias.pdf

Download PDF (174.1 KB)Supplementary_3_Checklist_Risk_of_bias_Cohort.xlsx

Download MS Excel (19.1 KB)Supplementary_2_Excluded_studies.pdf

Download PDF (226.7 KB)Supplementary_1_Search_strategy.pdf

Download PDF (206.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbott MW, Binde P, Clark L, Hodgins DC, Johnson MR, Manitowabi D, Quilty L, Spångberg J, Volberg R, Walker D, et al. 2018. Conceptual framework of harmful gambling.

- Alderson P. 2004. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 328(7438):476–477.

- Auer M, Griffiths MD. 2013. Voluntary limit setting and player choice in most intense online gamblers: an empirical study of gambling behaviour. J Gambl Stud. 29(4):647–660.

- Auer M, Griffiths MD. 2015a. The use of personalized behavioral feedback for online gamblers: an empirical study. Front Psychol. 6:1406.

- Auer M, Griffiths MD. 2015b. Testing normative and self-appraisal feedback in an online slot-machine pop-up in a real-world setting. Front Psychol. 6:339.

- Auer M, Griffiths MD. 2016. Personalized behavioral feedback for online gamblers: a real world empirical study. Front Psychol. 7:1875.

- Auer M, Malischnig D, Griffiths M. 2014. Is “pop-up” messaging in online slot machine gambling effective as a responsible gambling strategy? J Gambl Issues. 29:1–10.

- Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, Grube J, Hill L, Holder H, Homel R, et al. 2010. Alcohol, no ordinary commodity: research and public policy. New York (NY): Oxford University Press.

- Blaszczynski A, Collins P, Fong D, Ladouceur R, Nower L, Shaffer HJ, Tavares H, Venisse JL. 2011. Responsible gambling: general principles and minimal requirements. J Gambl Stud. 27(4):565–573.

- Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Nower L. 2008. Informed choice and gambling: principles for consumer protection. J Gambl Bus Econ. 2(1):103–118.

- Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Shaffer HJ. 2004. A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. J Gambl Stud. 20(3):301–317.

- Broussard J, Wulfert E. 2017. Can an accelerated gambling simulation reduce persistence on a gambling task? Int J Ment Health Addict. 15(1):143–153.

- Caillon J, Grall-Bronnec M, Perrot B, Leboucher J, Donnio Y, Romo L, Challet-Bouju G. 2019. Effectiveness of at-risk gamblers’ temporary self-exclusion from internet gambling sites. J Gambl Stud. 35(2):601–615.

- Canale N, Vieno A, Griffiths MD. 2016. The extent and distribution of gambling-related harms and the prevention paradox in a British population survey. J Behav Addict. 5(2):204–212.

- Canale N, Vieno A, Griffiths MD, Marino C, Chieco F, Disperati F, Andriolo S, Santinello M. 2016. The efficacy of a web-based gambling intervention program for high school students: a preliminary randomized study. Comput Hum Behav. 55:946–954.

- Celio MA, Lisman SA. 2014. Examining the efficacy of a personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce college student gambling. J Am Coll Health. 62(3):154–164.

- Cunningham JA, Hodgins DC, Toneatto T, Murphy M. 2012. A randomized controlled trial of a personalized feedback intervention for problem gamblers. PLoS One. 7(2):e31586.

- Doiron JP, Nicki RM. 2007. Prevention of pathological gambling: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 36(2):74–84.

- Donati MA, Primi C, Chiesi F. 2014. Prevention of problematic gambling behavior among adolescents: testing the efficacy of an integrative intervention. J Gambl Stud. 30(4):803–818.

- Dowling NA, Cowlishaw S, Jackson AC, Merkouris SS, Francis KL, Christensen DR. 2015. Prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity in treatment-seeking problem gamblers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 49(6):519–539.

- Floyd K, Whelan JP, Meyers AW. 2006. Use of warning messages to modify gambling beliefs and behavior in a laboratory investigation. Psychol Addict Behav. 20(1):69–74.

- Forsström D, Hesser H, Carlbring P. 2016. Usage of a responsible gambling tool: a descriptive analysis and latent class analysis of user behavior. J Gambl Stud. 32(3):889–904.

- Forsström D, Jansson-Fröjmark M, Hesser H, Carlbring P. 2017. Experiences of Playscan: interviews with users of a responsible gambling tool. Internet Intervent. 8:53–62.

- Forsström D, Rafi J, Carlbring P. 2020. Drop outs usage of a responsible gambling tool and subsequent gambling patterns. Cogent Psychol. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1715535

- Ginley MK, Whelan JP, Keating HA, Meyers AW. 2016. Gambling warning messages: the impact of winning and losing on message reception across a gambling session. Psychol Addict Behav. 30(8):931–938.

- Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann H. 2008. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 336(7650):924–926.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Rind D, Devereaux P.J, Montori V M, Freyschuss B, Vist G, et al. 2011. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence–imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol. 64(12):1283–1293.

- Hancock L, Smith G. 2017a. Replacing the Reno model with a robust public health approach to “responsible gambling”: Hancock and Smith’s response to commentaries on our original Reno model critique. Int J Ment Health Addict. 15(6):1209–1220.

- Hancock L, Smith G. 2017b. Critiquing the Reno Model I-IV international influence on regulators and governments (2004–2015)—the distorted reality of “responsible gambling. Int J Ment Health Addict. 15(6):1151–1176.

- Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Savovic J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, Reeves B, Eldridge S. 2016. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Syst Rev. 10(1):29–31.

- Ivanova E, Rafi J, Lindner P, Carlbring P. 2019. Experiences of responsible gambling tools among non-problem gamblers: a survey of active customers of an online gambling platform. Addict Behav Rep. 9:100161.

- Jardin B, Wulfert E. 2009. The use of messages in altering risky gambling behavior college students: an experimental analogue study. Am J Addict. 18(3):243–247.

- Jardin BF, Wulfert E. 2012. The use of messages in altering risky gambling behavior in experienced gamblers. Psychol Addict Behav. 26(1):166–170.

- Jonsson J, Hodgins DC, Munck I, Carlbring P. 2019. Reaching out to big losers: a randomized controlled trial of brief motivational contact providing gambling expenditure feedback. Psychol Addictiv Behav. 33(3):179–189.

- Keen B, Blaszczynski A, Anjoul F. 2017. Systematic review of empirically evaluated school-based gambling education programs. J Gambl Stud. 33(1):301–325.

- Kim HS, Wohl MJA, Stewart MJ, Sztainert T, Gainsbury SM. 2014. Limit your time, gamble responsibly: setting a time limit (via pop-up message) on an electronic gaming machine reduces time on device. Int Gambl Stud. 14(2):266–278.

- Kotter R, Kraplin A, Buhringer G. 2018. Casino self- and forced excluders’ gambling behavior before and after exclusion. J Gambl Stud. 34(2):597–615.

- Kuritz SJ, Landis JR, Koch GG. 1988. A general overview of Mantel-Haenszel methods: applications and recent developments. Annu Rev Public Health. 9(1):123–160.

- Ladouceur R, Ferland F, Vitaro F, Pelletier O. 2005. Modifying youths’ perception toward pathological gamblers. Addict Behav. 30(2):351–354.

- Ladouceur R, Goulet A, Vitaro F. 2013. Prevention programmes for youth gambling: a review of the empirical evidence. Int Gambl Stud. 13(2):141–159.

- Ladouceur R, Shaffer P, Blaszczynski A, Shaffer HJ. 2017. Responsible gambling: a synthesis of the empirical evidence. Addict Res Theory. 25(3):225–235.

- Ladouceur R, Sylvain C, Gosselin P. 2007. Self-exclusion program: a longitudinal evaluation study. J Gambl Stud. 23(1):85–94.

- Langham E, Thorne H, Browne M, Donaldson P, Rose J, Rockloff M. 2015. Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health. 16(1):80.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux P. J, Kleijnen J, Moher D. 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 6(7):e1000100.

- Lorains FK, Cowlishaw S, Thomas SA. 2011. Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addict. 106(3):490–498.

- Lupu IR, Lupu V. 2013. Gambling prevention program for teenagers. J Cognit Behav Psychother. 13(2):575–584.

- Marchica L, Derevensky JL. 2016. Examining personalized feedback interventions for gambling disorders: a systematic review. J Behav Addict. 5(1):1–10.

- Martens MP, Arterberry BJ, Takamatsu SK, Masters J, Dude K. 2015. The efficacy of a personalized feedback-only intervention for at-risk college gamblers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 83(3):494–499.

- McCormick AV, Cohen IM, Davies G. 2018. Differential effects of formal and informal gambling on symptoms of problem gambling during voluntary self-exclusion. J Gambl Stud. 34(3):1013.

- McMahon N, Thomson K, Kaner E, Bambra C. 2019. Effects of prevention and harm reduction interventions on gambling behaviours and gambling related harm: an umbrella review. Addict Behav. 90:380–388.

- Merkouris SS, Thomas AC, Shandley KA, Rodda SN, Oldenhof E, Dowling NA. 2016. An update on gender differences in the characteristics associated with problem gambling: a systematic review. Curr Addict Rep. 3(3):254–267.

- Meyer G, Kalke J, Hayer T. 2018. The impact of supply reduction on the prevalence of gambling participation and disordered gambling behavior: a systematic review. Sucht. 64(5–6):283–293.

- Motka F, Gruene B, Sleczka P, Braun B, Örnberg JC, Kraus L. 2018. Who uses self-exclusion to regulate problem gambling? A systematic literature review. J Behav Addict. 7(4):903–916.

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. 2008. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies.

- Neighbors C, Rodriguez LM, Rinker DV, Gonzales RG, Agana M, Tackett JL, Foster DW. 2015. Efficacy of personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for college student gambling: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 83(3):500–511.

- Nelson SE, Kleschinsky JH, LaBrie RA, Kaplan S, Shaffer HJ. 2010. One decade of self exclusion: Missouri casino self-excluders four to ten years after enrollment. J Gambl Stud. 26(1):129–144.

- Nelson SE, LaPlante DA, Peller AJ, Schumann A, LaBrie RA, Shaffer HJ. 2008. Real limits in the virtual world: self-limiting behavior of internet gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 24(4):463–477.

- Oh BC, Ong YJ, Loo JM. 2017. A review of educational-based gambling prevention programs for adolescents. Asian J Gambl Issues Public Health. 7(1):4.

- Raisamo SU, Mäkelä P, Salonen AH, Lintonen TP. 2015. The extent and distribution of gambling harm in Finland as assessed by the Problem Gambling Severity Index. Eur J Public Health. 25(4):716–722.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. 2015. Version 5.3. Copenhagen (Denmark): The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Rockloff MJ, Donaldson P, Browne M. 2015. Jackpot expiry: an experimental investigation of a new EGM player-protection feature. J Gambl Stud. 31(4):1505–1514.

- Romild U, Svensson J, Volberg R. 2016. A gender perspective on gambling clusters in Sweden using longitudinal data. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 33(1):43–60.

- Sharpe L, Walker M, Coughlan MJ, Enersen K, Blaszczynski A. 2005. Structural changes to electronic gaming machines as effective harm minimization strategies for non-problem and problem gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 21(4):503–520.

- Steenbergh TA, Whelan JP, Meyers AW, May RK, Floyd K. 2004. Impact of warning and brief intervention messages on knowledge of gambling risk, irrational beliefs and behaviour. Int Gambl Stud. 4(1):3–16.

- Sterne J A, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, et al. 2016. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 355:i4919.

- Stewart MJ, Wohl MJ. 2013. Pop-up messages, dissociation, and craving: how monetary limit reminders facilitate adherence in a session of slot machine gambling. Psychol Addict Behav. 27(1):268–273.

- St-Pierre RA, Derevensky JL, Temcheff CE, Gupta R, Martin-Story A. 2017. Evaluation of a school-based gambling prevention program for adolescents: efficacy of using the theory of planned behaviour. J Gambl Issues. 36:113–137.

- Turner N, Macdonald J, Bartoshuk M, Zangeneh M. 2008. The evaluation of a 1-h prevention program for problem gambling. Int J Ment Health Addict. 6(2):238–243.

- Turner NE, Macdonald J, Somerset M. 2008. Life skills, mathematical reasoning and critical thinking: a curriculum for the prevention of problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. 24(3):367–380.

- Walker M, Toneatto T, Potenza MN, Petry N, Ladouceur R, Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N, Echeburua E, Blaszczynski A. 2006. A framework for reporting outcomes in problem gambling treatment research: The Banff, Alberta Consensus. Addict. 101(4):504–511.

- Williams RJ, Connolly D. 2006. Does learning about the mathematics of gambling change gambling behavior? Psychol Addict Behav. 20(1):62–68.

- Williams RJ, West BL, Simpson RI. 2012. Prevention of problem gambling: a comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

- Williams RJ, Wood RT, Currie SR. 2010. Stacked Deck: an effective, school-based program for the prevention of problem gambling. J Primary Prevent. 31(3):109–125.

- Wohl MJ, Christie KL, Matheson K, Anisman H. 2010. Animation-based education as a gambling prevention tool: correcting erroneous cognitions and reducing the frequency of exceeding limits among slots players. J Gambl Stud. 26(3):469–486.

- Wohl MJA, Parush A, Kim HS, Warren K. 2014. Building it better: applying human–computer interaction and persuasive system design principles to a monetary limit tool improves responsible gambling. Comput Hum Behav. 37:124–132.

- Wood RTA, Wohl M. 2015. Assessing the effectiveness of a responsible gambling behavioural feedback tool for reducing the gambling expenditure of at-risk players. Int Gambl Stud. 15(2):1–16.