Abstract

Young people who use substances rarely access addiction services. When access does occur, the relationship between professionals and users is often described as difficult because of mutual distrust. This results in low motivation for treatment and limited involvement in decision-making. This study aims to investigate the perspectives of young who used substances to understand their motivations for access, both stated and unexpressed. Four focus groups were conducted with twenty people who used substances and had access to an addiction service during youth. The narratives were analyzed through thematic analysis and identity positioning. Participants reported three reasons for accessing the service: ‘Legal issues’, ‘Obtaining substances’ and ‘Reassuring the family’. Various personal positions emerged with respect to access, differing by content but united by a prevailing role passivity. The findings allow us to rethink some of the limitations inherent in established service practices. Some reflections ensue about the ways in which more authentic dialogue could be fostered, favoring the explication of those ‘truths’ that are generally not shared in early encounters and that pose a threat to the success of many therapeutic pathways.

Introduction

Research regarding substance use in the youth population has recently highlighted numerous profound changes (Iudici et al. Citation2015; Kraus and Nociar Citation2016; Knapp et al. Citation2019; Biagioni et al. Citation2023). The phenomenon of substance use is transforming and becoming more complex, thus requiring an updating of knowledge (Zuffa et al. Citation2014; Orsolini et al. Citation2017; Castelpietra et al. Citation2022; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Citation2022). Constant updating is the challenge of today’s services (Peacock et al. Citation2019).

Some services have been unable to adapt to the characteristics of youthFootnote1 who use substances, remaining anchored in a historical mandate that makes them distant from society and anachronistic in promoting health (Chandra and Minkovitz Citation2007; Ali et al. Citation2022). In this historical period, two social phenomena, which are also complementary, have a strong impact on limiting the number of accesses to services: normalization of consumption (Parker et al. Citation1999) and stigmatization (Pedersen and Paves Citation2014). In the first case, users can be described as socially integrated people who use substances for recreational purposes and are successful in school and professional life (Riley et al. Citation2001; Duff Citation2005). As such, these young people are hardly intercepted by services (Pavarin Citation2015).

Substance use can be considered as a deliberate search for gratifying effects, instrumental in generating changes in the psychological state (e.g. changing or confirming self-concept, experiencing new sensations and sharing specific experiences within the group) (Iudici et al. Citation2015).

The second phenomenon that contributes to reduced treatment utilization is the problem of stigma, which has gained significance as the age of service entry has lowered (Adlaf et al. Citation2009), given also the low perceived confidentiality of youth who use substances (Stern et al. Citation2007). Many young people might not seek help because of the effects of stigma that is triggered by attending services and tend to stigmatize the services themselves. This leads them to have a persistent problem and to consolidate a distance between themselves and the helping professionals in charge of these interventions (Tharaldsen et al. Citation2017).

The combination of these two processes, normalization of consumption and stigmatization of the service and service users, contributes to the fact that consumption and substance abuse occur in solitude, deterring the young people from seeking help (Ali et al. Citation2022).

The literature also identifies other barriers to treatment access: long waiting lists, mobility problems and treatment costs (Wisdom et al. Citation2011; Russell et al. Citation2019).

When accesses occur, the interaction between a service and a user takes on a highly complicated dynamic. Some research has shown that the relationship between service professionals and service users is characterized by ‘mutual mistrust’, a dynamic is formed in which practitioners’ fear of deception interacts with that of mistreatment or stigmatization of users (Merrill et al. Citation2002). Some studies have found that users feel incomprehended by the staff (Ferguson et al. Citation2019), and others have found that the staff have an unhelpful attitude toward the users’ problems (Howard and Holmshaw Citation2010; Janeiro et al. Citation2018).

Given this background, developing a trusting relationship between practitioners and users remains a necessary element for services, as it helps to contrast dropout rates (Iudici et al. Citation2022) and allows users to be involved in treatment decisions (Kraetschmer et al. Citation2004; Park et al. Citation2020). Involving users in decision-making today is central to all treatment planning, as confirmed by shared decision-making models (Charles et al. Citation1997; Elwyn et al. Citation2012; Faccio et al. Citation2022), as well as for people who used substances (Ness et al. Citation2017; Marchand et al. Citation2019).

Initial access opens the door to a challenging treatment process in which the person may not recognize himself, or only partially (Faccio et al. Citation2021). It is also possible that the person decides to access a service for reasons different from the ones they declare in the first interview, given the difficulty in placing trust in professionals. Some of these motives might be contradictory to the mandate of the service itself, and thus, might not be shareable with professionals (Holt Citation2007). Hence, there is a certain tendency to move according to stereotypical roles and masquerading of one’s story (Faccio and Costa Citation2013). Users choose what to say and not to say to the staff (Granerud and Toft Citation2015) and adopt strategies for not revealing certain information about themselves that is perceived as obstructive to their masked goal (Grønnestad and Sagvaag Citation2016; Faccio et al. Citation2022).

Accessing this information would make it possible to update and improve the operational practices of services, but more importantly, it would allow working with people from their actual needs rather than overwriting them based on the service mission statement (Faccio et al. Citation2023).

This study aims to understand the views of those who access a service during youth, trying to reconstruct experiences and thoughts related to the delicate phase of access. It attempts to examine in depth the intimate reasons that motivated young people to access the service. The purpose is to explore the difficulties and ambivalences experienced. We believe that these data could be useful for bringing services closer to young users and constructing shared intervention proposals based on their specific needs. For this purpose, a specific research design was developed, given the difficulty of collecting narratives that are often not shared with service professionals.

Methodology

The research methodology was set following the guidelines of the APA Task Force Report for Qualitative Research Standards (Levitt et al. Citation2018).

Settings and participants

Our goal is to collect and analyze accounts of young people’s first access to addiction services. In Italy, this usually takes place at SerD (Addiction Services) or at the public outpatient services for pathological addictions of the Italian National Health System, whose mission concerns the primary prevention, the prevention of related pathologies, rehabilitation and social and work reintegration activities. They also work in collaboration with therapeutic communities, municipal administrations and voluntary organizations. In general, they provide initial support and guidance to people who use substances and their families. In particular, they define individual therapeutic programmes as being carried out in their own operational centers or in cooperation with an accredited therapeutic community. They cover different types of interventions, such as consumption reduction or harm reduction, not only abstinence-oriented projects.

We proposed to young people who had had their first access to the service between the ages of 15 and 24 to participate in the research. Our inclusion criteria required that they were on a therapeutic journey in the same community, and they knew each other quite well -this to facilitate communication; the community had to be different from the SerD- this to allow greater freedom of expression and to avoid conflicts of interest. A second criterion was that 2–10 years had passed since the first access.

To recruit these people, we sought and obtained cooperation from a therapeutic community in inpatient services. People knew each and the researcher who collected the data because he had spent a period of six months in the therapeutic community for an internship. The researcher presented to the members of the community the research strategies, the aims and the way in which the data would be protected and analyzed. The research will be conducted in an inside space that the community makes available. Adhesions to the research were collected two weeks after the presentation.

The mutual familiarity between the participants and researcher, a figure recognized as spurious of value judgements and with whom certain themes had already been made available in previous interactions, made it possible to make otherwise forbidden discourses accessible. As stated also by the literature (Blichfeldt and Heldbjerg Citation2011), this methodological choice can lead to a more relaxed atmosphere and greater sharing of information. Doing research with known people, on the other hand, may lead to privacy problems, as much more personal information may be shared and acquaintances may feel obliged to participate (Blichfeldt and Heldbjerg Citation2011). We tried to manage the second issue by proposing the research to the community as a free group rather than inviting individual members. In fact, not the whole community participated. The choice to involve interviewers with in-depth knowledge of the topic and the participants’ life issues is also supported by the literature (Elliott et al. Citation2002).

Twenty people took part in the research and four focus groups were conducted, each of which was composed of a moderator, a collaborator and five participants. They were all males and the average age at the time of participation in the research was 27, with the range between 18 and 31, while the age at which they first approached the Addiction Service was 17, with the range between 15 and 20. The group division is explicitly explained in .

Table 1. Focus group composition and characteristics of participants.

Data collection

The use of the focus group as a methodology provides a process and an interactive setting for the reflection, exchange and co-construction of data concerning an object of investigation. It helps to investigate meanings, collective opinions and social considerations more deeply and richly than individual interviews (Thomas et al. Citation1995). The focus groups were conducted with a ‘moderated’ level of structuring (Cardano Citation2003), which means that the discussion took place following the themes proposed by the moderator for 2 h each. In addition, three vignettes were proposed, accompanied by some keywords that were aimed at focusing on the themes of the discussion and evoking specific past moments of the service access phase. The first vignette depicted a young person on his way to an addiction treatment service, the second depicted the exchange that took place with peers before approaching the service and the third depicted the moment of interview with service professionals. The focus groups were conducted in five stages, which were freely discussed in depth in the various groups:

Research presentation and atmosphere warming

First theme: ‘Access to the service’

Second theme: ‘The beliefs people had about the service’

Third theme: ‘The ways in which people narrated themselves to the service’

Closing: The facilitators shared comments on the discussion’s progress, the topics that received the most attention and those that were unexpected

The focus groups were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. In compliance with ethical standards, the researchers informed the participants of their right to withdraw from the focus groups at any time and obtained their informed consent to participate in the study. We presented the material anonymously and obtained approval from the University of Padova Faculty of Psychology ethics committee.

Data analysis

The collected material was analyzed by thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2012, Citation2019) and positioning analysis (Riessman Citation2003; Bamberg Citation2004). In the first case, recurrent ‘themes’ within the narratives were traced (Boyatzis Citation1998) based on the theoretical aims and assumptions of the research (Holloway and Todres Citation2003).

In line with the aims of Thematic Analysis (TA), we decided to use this first tool, as it allows, by focusing on the meaning of a set of data, to make sense of collective or shared meanings and experiences. Through this method, it is possible to identify what is common in the way people talk or write about a topic and to make sense of these commonalities.

As presented in the TA guidelines by Braun and Clarke (Citation2012), it is necessary to specify that a deductive, critical, constructionist approach was used in this article, starting from the codes and themes derived from the content of the data. What is explored by the researcher during the analysis corresponds closely to the content of the data, examining how the world is constructed and the ideas and assumptions that inform the data gathered.

Discursive positioning analysis is usually considered a useful tool in the study of identity construction and performance (Riessman Citation2003; Bamberg Citation2004). It considers identity as a phenomenon realized ‘by’ and ‘in’ discourse (Deppermann Citation2015), where the act of positioning oneself in a discourse involves assigning roles to the characters that make up the story being told. Thus, observing the discursive modes that are used to position characters provides access to a specific way of seeing the world and making meaning of experience (Harré and Van Langenhove Citation1999). This methodology of analysis was declined by following and adapting Bamberg’s (Citation1997) conceptualization to the objectives of the present research. In particular, its use allowed for a broader look at the phenomenon in question. It is not limited to the collection of content but investigates the ‘position’ the person takes toward what they are talking about. One’s role or attitude with respect to a service access can be constructed in linguistically very different ways (Faccio et al. Citation2011). Of the three questions that Bamberg (Citation1997) proposed to ask the texts under analysis, one was explored in depth, which in the context of the present research sounds like this: ‘How did the characters position themselves in relation to the service access story?’ Several narrative positions emerged, which were ordered using intentionality as the superordinate semantic dimension. Thus, a theoretical continuum was defined whose polarities express, respectively, the highest and lowest degrees of intentionality or active role to the positions taken by the participants.

The analysis was carried out according to these steps, in line with those of thematic analysis: familiarization with the data, collection of all extracts in which access to the service was narrated; description of the discursive position taken in each extract through a label and comparison, amalgamation and redefinition of the label expressing the positions described through the criteria of ‘internal homogeneity’ and ‘external heterogeneity’ (Patton Citation1990). At this point, a list of the main discursive positions was compiled; the text was revised considering this final list, and a report was produced, as shown below.

Findings

The data on how participants experienced and narrated the moment of their access to the service are divided into two sections related to the analysis methods used. The first section presents how the participants positioned themselves in the narrative of their choice to access the service. The second section presents an analysis of the recurrent themes with which the narrative of accessing the service was constructed.

Re-telling the choice of accessing the service

The particularity of this research is expressed in an attempt to access narratives that are different from those that a young consumer usually shares with the service they address—narratives that are often omitted or masked.

I had to tell the service that my goal was to stop using substances. (Focus group n.1)

Many participants recounted that, in front of the service practitioners, they had chosen to present themselves as motivated by the goal to stop using substances, obscuring many other reasons related to the decision to access.

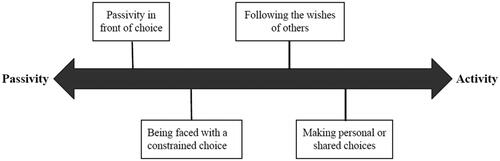

Four different discursive ways of positioning oneself with respect to the ‘access to service’ event emerged from the analysis. They are placed on a continuum that expresses the different degrees of intentionality that the narrator ascribes to themselves in narrating the event. Starting with the most passive position, we created the following four descriptive labels: ‘Passivity in front of choice’, ‘Being faced with a constrained choice’, ‘Following the wishes of others’ and ‘Making personal or shared choices’ ().

In addition to these four positionings, it should be noted that many of the participants positioned themselves in the role of those who felt unsuitable to access, as the service was perceived as being devoted to older people with more problematic histories of drug addiction. The stigmatization of services, therefore, also plays a role in the choice to access them.

Let’s start from the premise that when I went there it was gloomy, ugly, then there were older people who were junkies… people in their 40s who went there to give urine. Already for me the presence of an older person and seeing that I was the youngest person there made me ask two questions. (Focus group n.3)

Passivity in front of choice

In several of the narratives, the participants described themselves as completely passive considering the decision to access the service; they described themselves as subjects without the power to choose or act differently. For example, some in the narrative position themselves in the role of those who did not ‘go to the service’ but ‘were sent’ or ‘mandatorily brought’ to it. They configured the intention to go to the service as something that does not belong to themselves but to someone else.

Following a substance use complaint, when I was fifteen years old, the social worker decided to send me to the service. (Focus group n.3)

I was fifteen and she (my mother, ed.) took me there. (Focus group n.1)

Another narrative mode characterized by the position of ‘Passivity in front of choice’ is one that recounts the service access as something caused by an external factor, with respect to which there was no alternative possibility; thus, the service access is configured as inevitable. Scenarios described as ‘causing’ access to the service include situations in which ‘one could no longer manage substance use’, ‘my family had found out I was a user’ or ‘huge messes had been made’.

I had made a mess with family and friends, at which point the only thing I could do was go to the service. (Focus group n.3)

Again, therefore, access takes the form of being dictated by conditions of contingency, although it is the result of a personal movement. The focus is on a scenario in which “choice” is produced within the “one choice”.

Being faced with a constrained choice

Another mode that emerged is one in which people narrated that they were faced with a constrained choice: ‘either I turn to the service, or…’. Compared to the previous modality, in this case, the person is configured as the master of their own choice; however, a passivity of position remains, considering that the choice of having turned to the service is configured as necessary to avert undesirable consequences. The narrator is placed in the role of one who has been faced with a crossroads: on one hand, the service and, on the other hand, the undesirable consequence.

At the beginning, I think it’s like that for everyone. I too went into the service because if not, my sister would not let me have relations with my nephews. (Focus group n.3)

I was forced to go […]. By doing that, my license would not have gone on review. (Focus group n.4)

Following the wishes of others

In other texts, the narrator always narrates their own choice of access as intentional but acknowledges that this intention does not reflect their own will, but rather that of others, such as family members. Thus, it can be described as the role in which they recount themselves as one who has gone along on someone else’s request.

Substance use for me was not a serious problem; therefore, I personally would not have gone there. Then my mom was so insistent, so I went. (Focus group n.3)

My mother went, then as a favor to her… she was more tranquil if I went, so I started. (Focus group n.1)

Making personal or shared choices

The last mode of positioning is that of the person who tells themselves as the owner of their choice, made because of a personal goal. The person narrates themselves within the stereotypical model of a subject who acts by reason of motivation.

I turned to the service to keep up the pace of life, try to lighten it up a bit because one cannot buy heroin every day, methadone acts as a bit of a buffer. (Focus group n.1)

Personal goals might also have been co-constructed with family members, for example, or might have been about substitute drug prescriptions.

I was always very direct, that is, I only ever went to the service for (methadone) treatment. (Focus group n.4)

They told us that there was this service, so together with my family, I chose to go there. (Focus group n.2)

Motivations often hidden behind service access

Through thematic analysis, it was found that the motivations that lead a person to access a service can be of various types and very often unrelated to the explicit goals of the service. Several participants told us how, when faced with a service practitioner, they found themselves in the role of someone who had to admit that ‘drugs are a problem’ or that ‘I want to stop using drugs’, even though the reasons behind the request for access may be different from these.

Let’s say I presented myself to the doctor as a problem person, meaning I have a thousand problems, my life is shit and all this kind of stuff because it was right to do that. (Focus group n.2)

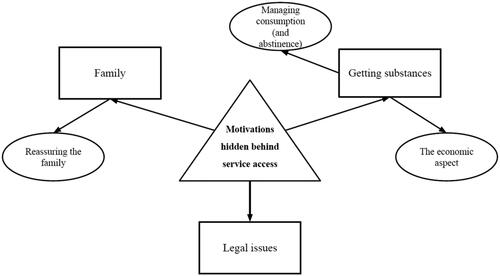

The contents that emerged related to service access were grouped into three main thematic areas: ‘Family’, ‘Getting substances’ and ‘Legal issues’. As shown in the , the thematic area ‘Family’ has one sub-theme: ‘Tranquilizing the family’. The thematic area ‘Obtaining substances’ has two: ‘The economic aspect’ and ‘Managing consumption (and abstinence).’ We will now explain these contents.

Family

Within this group of text extracts, access to a service is associated with various contents related to the family system, such as ‘mom’, ‘dad’ and ‘sister’.

Initially, the reason – I was hoping to stop, but not for myself. That is, my parents had caught me … more for the family than for Myself. (Focus group n.4)

Oh God, voluntarily is a big word, I was forced to go there by my parents. (Focus group n.3)

Tranquilizing the family

In many narratives of the ‘family’ content, the reason related to accessing a service is explicitly to use the service as a strategy to ‘tranquilise the family’ and demonstrate that one is moving toward stopping substance use and thus avoid receiving pressure.

The idea was … I take methadone, keep my mother quiet, but at the same time, I keep using drugs. (Focus group n.1)

(Accessing the service, ed.) The only thing that can ascertain to my mom that I am a good boy. (Focus group n.3)

In this second narrative, the service is used as a certification offered to the family for the cessation of substance use, even when this actually does not happen.

Obtaining substances

This second dominant theme comprises a set of narratives within which access to a service is configured in connection with the possibility of receiving drug therapies, mainly methadone, suboxone and psychotropic medications—an element that, in several cases, rises as a fundamental reason for the choice and not for its therapeutic value.

When you come into the service, it’s not like you’re hoping the psychologist will be there… That is, you come in for (Methadone) therapy; it’s not like you want to have an hour-long interview. (Focus group n.2)

The economic aspect

Within the excerpts of text naming this sub-theme, the drug therapy received through the service is configured as being useful in managing the costs associated with substance use or in earning money through the resale of medications, so much so that the service was also referred to as a ‘free drug bank’. Faced with the economic inability to purchase substances and the fear of experiencing withdrawal for some users, substitution therapies took on the value of a safety anchor.

The guys I was hanging around with were almost all going, I was the last one left who didn’t want to go. However, not always finding the money to use drugs… (Focus group n.1)

The substance received from the service could also be put on the market for earning extra money.

I didn’t know anyone who went to the service and was better off, one was better off just out of pocket, out of wallet. I knew one who went to the service and…. at home had boxes of methadone, went every week and came back with a shoulder bag full of big bottles of methadone. There are many who sell it. (Focus group n.4)

Management of consumption (and abstinence)

This second sub-theme was generated with the intention of showing how the pursuit of drug therapy is also configured, paradoxically, as an element capable of sustaining substance use rather than counteracting it, since, in the configuration, consumption would become unsustainable without therapy. So much so that in one of the narratives, the reason for accessing the service to take methadone was supported by the fact that methadone allows one to ‘continue quietly’ (i.e. to be able to better manage substance use and the undesirable effects due to the lack of the it).

The idea was I need something additional to keep my life going’, so the idea is not to go there to get help to stop taking substances, but to get an alternative medication that will still allow me to continue using and on the other side to be able to keep up the rest of the things I have, work and everything else. (Focus group n.4)

Legal issues

The last theme of this analysis is that of ‘Legal issues’. One can indeed choose to attend a service as an alternative to prison.

‘I remember coming out of the prison gate and standing with my father and my lawyer on the bench, the lawyer says to me, ‘you have to go to a service to serve your sentence, go there take it easy, so the judge sees that…’. (Focus group n.4)

Again, a service access can be made given the possibility of regaining a driver’s license and thus without any other therapeutic purpose.

The social worker at the prefecture had proposed that I do a six-month course at the service, take urine twice a week, and by doing that my license would not go on review. (Focus group n.4)

Discussion

The objective of this study was to understand the hidden motivations and underlying ways in which young people come to a service for people who use substances. There are two main findings: (1) the roles in which users describe themselves at the moment of accessing services are characterized by a range of variable positions within a continuum between active and passive and (2) the referred reasons for accessing services are often, completely or partially, disconnected from substance use.

The analysis of discursive positions showed that, for many young people, service access is not related to personal goals. They experience and narrate access by placing themselves in a passive position in which the event is configured as inevitable, compelled by situations or figures outside the narrative.

This finding has strong implications with regard to the implementation of models involving the construction of shared therapeutic projects with users, a strategy that is becoming increasingly popular today (Iudici et al. Citation2022), as in the case of shared decision-making applied to substance use services (Joosten et al. Citation2009, Citation2011). In particular, considering that many young people arrive at services without defined goals, but are brought in forcibly by others, motivates us to rethink service access interviews by considering them useful not so much for ‘sharing goals’ but rather for laying the groundwork for being able to ‘imagine goals together’. The construction of a shared goal (of a mission statement), therefore, may be the first purpose to be achieved with a user. The clinician’s attention to the meaning the person attaches to their service access enables and compels the carving out of proposals based on it. Remaining adherent to these meanings can be a useful strategy to counter the possibility of creating fictitious therapeutic plans within which the work of practitioners and users follows personal, unshared and therefore cultivated trajectories in solitude (Faccio et al. Citation2022). This first type of analysis also emphasized that, in service access narratives, the user does not see themselves as the sole protagonist but includes other figures, such as family members. The finding that a service access can be dictated by motivations such as ‘I make my mom feel calm’ is crucial for practitioners. This implies the need to consider ad hoc strategies for family involvement, a practice that, to date, has almost never occurred in a structured manner (Orr et al. Citation2013), although it might yield better outcomes (Bjønness et al. Citation2022). This finding, in general, places practitioners in the face of the need to build therapeutic programmes with users that also take into consideration the effect that the programme can have on outsiders, using the increasingly popular perspective that understands recovery as inserted into a relational framework (Price-Robertson et al. Citation2017) and not strictly related to the single change of the individual (Romaioli and Faccio Citation2012).

Regarding the reasons that led young people to access services, it is salient to point out that use, as well as cessation of use, was often seen as a marginal issue: ‘I wasn’t interested in quitting drugs’, also in connection with the normalization of consumption in youth.

The discussions collected showed that this goal was often solicited by the service, which led young users to choose not to share other personal goals in order to present themselves within stereotypical forms, in line with their idea about services. For a mental health practitioner to move in stark contrast to the normalization of consumption risks placing their intervention in a position too distant from their users, preventing them from intercepting the person’s meanings, which are fundamental to the construction of a shared therapeutic pathway.

Working within the symbolic world of another person could also be a strategy to overcome the issue of mutual stigmatization and favor, in users, a new idea of the service rather than the one with which they arrived. It is essential that users perceive the services as appropriate for them and do not position themselves in roles that keep them distant from the services.

Focusing on the process of shared construction should be considered primary over the specific goal to be set, as this will change repeatedly over time (Laudet and White Citation2010). Primary is to participate in the therapeutic project, even though, as we have seen, some of the goals might be in opposition to those of services (White et al. Citation2014).

This study also allows us to reflect on the importance that the interactive context has in the collection of a life story: the results highlight how different interactive contexts can foster even very diverse accounts of the same story (Goffman Citation1959). In particular, the structuring of roles risks placing practitioners and users inside a game of parts in which the clinician is ‘the one who works to stop consumption’ and the user feels obliged to tell their story as ‘the one who wants to stop consuming’. Service providers should therefore pay close attention to the role dynamics that the recitation of an already established script tends to introduce in terms of performance and role expectations, as well as in terms of constraints placed on the free expression of all that the user may experience and think (Faccio et al. Citation2018). What is needed is a relational management style capable of moving interlocutors from the recitation of an already scripted role to the enactment of a dialogue, an exchange that takes into account what ‘cannot be said’ and activates an interactive process of openness to the dialogue.

This research has significant implications. Its results, in fact, allow us to identify certain modes of interaction between staff and users during the first interviews that can either bring the user closer to the service or push them away from it. A first indication concerns the de-emphasizing of aspects relating to the cessation of substance use so as not to trigger, on the part of the user, acting out of a role that may have a mere instrumental value. If entering the community is experienced as a passe-partout for other forms of “help” (legal, family and substitution therapy), it may be much more useful to devote attention to these secondary benefits, which the user may experience as primary.

It seems important to focus the first encounters on the knowledge of the young service user’s world; therefore, the questions asked during the interview are fundamental in order to investigate the potential and resources of the service user as a person. The professional has to try to explore the young person’s life project as broadly as possible through open-ended questions about their passions, leisure and recreational activities, as well as their study or work or travel plans. This can shift the focus to new discourses and dissuade from the recitation of a sort of “script” that research participants reported they had put on at the beginning.

Working on the goals that the person brings may be the first step in getting them to trust the professional and then, later in the process, to welcome exploring goals that they did not initially desire (including a change in their relationship with substances).

Another element that emerged to improve attitudes toward the service concerns the differentiation of services according to the age of the users. Some young people recounted that they felt the service was inappropriate for them because it was attended by “irredeemable addicts”, referring to adults with a long history of substance use and abuse. Differentiating the places and contexts of treatment could also help counter the stigma of youth toward services.

Limits and strengths of the study

The decision to investigate these topics by involving people who experienced them years earlier is both a limitation and a strength of this research. Retrospectivity allowed us to collect experiences that would otherwise have been inaccessible, but it is also a limitation because time changes memories and meanings, so we are aware that at different times, we would have collected different narratives, even from the same person. We preferred to meet the criterion of acquaintance between participants more strongly than the criterion of time since first access. While this facilitated the expression of personal and private issues related to ambivalence about access precisely because the participants knew each other, it also made it necessary to accommodate participants who were present in the same community at the same time, with different histories and times of access behind them.

Conclusions

Access to services for people who use substances is a topic of great complexity. Often, young people do not come to services of their own free will and are not even interested in stopping using drugs. These young people also find it difficult to share their stories in services because they see them as places that are not suitable for them. Operators of drug addiction services must pay close attention to the relational and role dynamics they put in place with their users to intercept their stories and create the conditions for effective collaboration, which is an indispensable element for the implementation of shared therapeutic programmes. The involvement of users in the various phases of the design, implementation and evaluation of services cannot be separated from the exercise of reflexivity, on the part of operators, on the effects results of their own practices. The analysis of users’ personal experiences is a fundamental part of clinical work, as it contributes to reconstructing and reorienting the mission of the service. As argued by Willig (Citation2019), the risks arising from a failure to elaborate on these “hidden truths” are those of failure of the process, due to incompatibility of perspectives or due to the imposition of the practitioners’ points of view on the client.

The motivations that young people have listed are the basis of any possible change. It is necessary to listen to these voices and satisfy them, even though they may seem far from the definitive cessation of substance use. Building a relationship of trust will go far beyond what young people have in mind in the initial phase of access. Therefore, professionals should engage with users’ explicit goals and motivations for access and, through these, formulate new co-constructed interactive scenarios.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology of the Padova University (No. 4838). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Michele Rocelli and Francesco Sdrubolini. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Michele Rocelli, Elena Faccio e Francesco Sdrubolini and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The first, the third and the fourth author contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work; the first and the second author drafted the paper and the fourth author revised it critically for important intellectual content. The second author collected the data. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data.

Acknowledgements

Special acknowledgement goes to all the people who participated in this research by making their stories available for the purpose of helping clinicians and users of future addiction services. Finally, thanks are also due to doctoral student (Ludovica Aquili) for the ideas and spirit she transmitted to the working group in designing the present research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Transcripts of all focus groups can be received by contacting the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We have referred to the criteria proposed by the WHO for the age division of the participants (WHO). WHO defines 'Adolescents' as individuals in the 10–19 years age group and 'Youth' as the 15–24 years age group. While 'Young People' covers the age range 10–24 years (World Health Statistics Citation2022).

References

- Adlaf EM, Hamilton HA, Wu F, Noh S. 2009. Adolescent stigma towards drug addiction: effects of age and drug use behaviour. Addict Behav. 34(4):360–364.

- Ali MM, Schreier A, West KD, Plourde E. 2022. Mental health conditions among children and adolescents with a COVID-19 diagnosis. PS. 73(12):1412–1413.

- Bamberg MG. 1997. Positioning between structure and performance. JNLH. 7(1–4):335–342.

- Bamberg M. 2004. Talk, small stories, and adolescent identities. Human Development. 47(6):366–369.

- Biagioni S, Baldini F, Baroni M, Cerrai S, Melis F, Potente R, Scalese M, Molinaro S. 2023. Adolescents’ psychoactive substance use during the first COVID-19 lockdown: a cross sectional study in Italy. Child Youth Care Forum. 52(3):641–659.

- Bjønness S, Grønnestad T, Johannessen JO, Storm M. 2022. Parents’ perspectives on user participation and shared decision‐making in adolescents’ inpatient mental healthcare. Health Expecta. 25(3):994–1003.

- Blichfeldt BS, Heldbjerg G. 2011. Why not? The interviewing of friends and acquaintances. Aalborg: Department of Entrepreneurship and Relationship Management, University of Southern Denmark.

- Boyatzis RE. 1998. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publication, Inc.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2012. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ, editors. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; p. 57–71.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Quali Res Sport Exer Health. 11(4):589–597.

- Cardano M. 2003. Tecniche di ricerca qualitativa. Percorsi di ricerca nelle scienze sociali. Roma: Carocci Editore; p.192–192.

- Castelpietra G, Knudsen AKS, Agardh EE, Armocida B, Beghi M, Iburg KM, Logroscino G, Ma R, Starace F, Steel N, et al. 2022. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990–2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 16:100341.

- Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. 2007. Factors that influence mental health stigma among 8th grade adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. 36(6):763–774.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. 1997. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 44(5):681–692.

- Deppermann A. 2015. Positioning 19. In: De Fina A, Georgakopoulou A, editors. Handbook of narrative analysis, Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Duff C. 2005. Party drugs and party people: examining the ‘normalization’of recreational drug use in Melbourne, Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy. 16(3):161–170.

- Elliott E, Watson AJ, Harries U. 2002. Harnessing expertise: involving peer interviewers in qualitative research with hard‐to‐reach populations. Health Expect. 5(2):172–178.

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S, et al. 2012. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 27(10):1361–1367.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 2022. European drug report 2022: trends and developments. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Faccio E, Aquili L, Rocelli, M, Anonymous . 2022. When the non-sharing of therapeutic goals becomes the problem: the story of a consumer and his addiction to methadone. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 29(2):174–180.

- Faccio E, Author A, Rocelli M. 2021. It’s the way you treat me that makes me angry, it’s not a question of madness: good and bad practice in dealing with violence in the mental health services. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 28(3):481–487.

- Faccio E, Aquili L, Bombieri M, Rocelli M. 2022. Is falling in love within the mental health system a problem? How to turn it into a chance for the care relationship. Psychiatric Ment Health Nurs. In press.

- Faccio E, Centomo C, Mininni G. 2011. Measuring up to measure" dysmorphophobia as a language game. Integr Psychol Behav Sci. 45(3):304–324.

- Faccio E, Costa N. 2013. The presentation of self in everyday prison life: reading interactions in prison from a dramaturgic point of view. Global Crime. 14(4):386–403.

- Faccio E, Mininni G, Rocelli M. 2018. What it is like to be “ex”? Psycho-discursive analysis of a dangling identity. Culture and Psychology,. 24(2):233–247.

- Faccio E, Pocobello R, Vitelli R, Stanghellini G. 2023. Grounding co-writing: an analysis of the theoretical basis of a new approach in mental health care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 30(1):123–131.

- Ferguson N, Savic M, McCann TV, Emond K, Sandral E, Smith K, Roberts L, Bosley E, Lubman DI. 2019. “I was worried if I don’t have a broken leg they might not take it seriously”: experiences of men accessing ambulance services for mental health and/or alcohol and other drug problems. Health Expect. 22(3):565–574.

- Goffman E. 1959. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: The Overlook Press.

- Granerud A, Toft H. 2015. Opioid dependency rehabilitation with the opioid maintenance treatment programme-a qualitative study from the clients’ perspective. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 10(1):1–9.

- Grønnestad TE, Sagvaag H. 2016. Stuck in limbo: illicit drug users’ experiences with opioid maintenance treatment and the relation to recovery. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 11(1):31992.

- Harré R, Van Langenhove L. 1999. Positioning theory. Blackwell: Oxford; p. 32–52.

- Holloway I, Todres L. 2003. The status of method: flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitat Res. 3(3):345–357.

- Holt M. 2007. Agency and dependency within treatment: drug treatment clients negotiating methadone and antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 64(9):1937–1947.

- Howard V, Holmshaw J. 2010. Inpatient staff perceptions in providing care to individuals with co‐occurring mental health problems and illicit substance use. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 17(10):862–872.

- Iudici A, Castelnuovo G, Faccio E. 2015. New drugs and polydrug use: implications for clinical psychology. Front Psychol. 6:267.

- Iudici A, Fenini D, Baciga D, Volponi G. 2022. The role of the admission phase in the Italian treatment setting: a research on individuating shared practices in psychotropic substance users’ communities. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 21(1):127–148.

- Janeiro L, Ribeiro E, Faísca L, Miguel MJL. 2018. Therapeutic alliance dimensions and dropout in a therapeutic community: bond with me and I will stay. TC. 39(2):73–82.

- Joosten EA, De Jong CAJ, De Weert-van Oene GH, Sensky T, Van der Staak CPF. 2009. Shared decision-making reduces drug use and psychiatric severity in substance-dependent patients. Psychother Psychosom. 78(4):245–253.

- Joosten EA, De Jong CA, de Weert-van Oene GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP. 2011. Shared decision-making: increases autonomy in substance-dependent patients. Subst Use Misuse. 46(8):1037–1038.

- Knapp AA, Lee DC, Borodovsky JT, Auty SG, Gabrielli J, Budney AJ. 2019. Emerging trends in cannabis administration among adolescent cannabis users. J Adolesc Health. 64(4):487–493.

- Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB. 2004. How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision‐making? Health Expect. 7(4):317–326.

- Kraus L, Nociar A. 2016. ESPAD report 2015: results from the European school survey project on alcohol and other drugs. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Laudet AB, White W. 2010. What are your priorities right now? Identifying service needs across recovery stages to inform service development. J Subst Abuse Treat. 38(1):51–59.

- Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, Frost DM, Josselson R, Suárez-Orozco C. 2018. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: the APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am Psychol. 73(1):26–46.

- Marchand K, Beaumont S, Westfall J, MacDonald S, Harrison S, Marsh DC, Schechter MT, Oviedo-Joekes E. 2019. Conceptualizing patient-centered care for substance use disorder treatment: findings from a systematic scoping review. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 14(1):1–15.

- Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. 2002. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 17(5):327–333.

- Ness O, Kvello Ø, Borg M, Semb R, Davidson L. 2017. “Sorting things out together”: young adults’ experiences of collaborative practices in mental health and substance use care. Am J Psychiat Rehab. 20(2):126–142.

- Orr LC, Barbour RS, Elliott L. 2013. Carer involvement with drug services: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 16(3):e60–e72.

- Orsolini L, Papanti D, Corkery J, Schifano F. 2017. An insight into the deep web; why it matters for addiction psychiatry? Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 32(3):e2573.

- Park SE, Mosley JE, Grogan CM, Pollack HA, Humphreys K, D'Aunno T, Friedmann PD. 2020. Patient-centered care’s relationship with substance use disorder treatment utilization. J Subst Abuse Treat. 118:108125.

- Parker H, Aldridge J, Measham F, Haynes P. 1999. Illegal leisure: the normalisation of adolescent recreational drug use. Health Education Research. 14(5):707–708.

- Patton MQ. 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Pavarin RM. 2015. Mortality risk among heroin abusers: clients and non-clients of public treatment centers for drug addiction. Subst Use Misuse. 50(13):1690–1696.

- Peacock A, Bruno R, Gisev N, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Sedefov R, White J, Thomas KV, Farrell M, Griffiths P. 2019. New psychoactive substances: challenges for drug surveillance, control, and public health responses. Lancet. 394(10209):1668–1684.

- Pedersen ER, Paves AP. 2014. Comparing perceived public stigma and personal stigma of mental health treatment seeking in a young adult sample. Psychiatry Res. 219(1):143–150.

- Price-Robertson R, Obradovic A, Morgan B. 2017. Relational recovery: beyond individualism in the recovery approach. Adv Mental Health. 15(2):108–120.

- Riessman CK. 2003. Analysis of personal narratives. In: Gubrium JD, Holstein JA, editors. Handbook of interview research: Context and method. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publishings, Inc.; p. 695–710.

- Riley SC, James C, Gregory D, Dingle H, Cadger M. 2001. Patterns of recreational drug use at dance events in Edinburgh, Scotland. Addiction. 96(7):1035–1047.

- Romaioli D, Faccio E. 2012. When therapists do not know what to do: informal types of eclecticism in psychotherapy. ResPsy. 15(1):10–21.

- Russell C, Neufeld M, Sabioni P, Varatharajan T, Ali F, Miles S, Henderson J, Fischer B, Rehm J. 2019. Assessing service and treatment needs and barriers of youth who use illicit and non-medical prescription drugs in Northern Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 14(12):e0225548.

- Stern SA, Meredith LS, Gholson J, Gore P, D'Amico EJ. 2007. Project CHAT: a brief motivational substance abuse intervention for teens in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 32(2):153–165.

- Tharaldsen KB, Stallard P, Cuijpers P, Bru E, Bjaastad JF. 2017. ‘It’sa bit taboo’: a qualitative study of Norwegian adolescents’ perceptions of mental healthcare services. Emot Behav Difficult. 22(2):111–126.

- Thomas L, MacMillan J, McColl E, Hale C, Bond S. 1995. Comparison of focus group and individual interview methodology in examining patient satisfaction with nursing care. Social Sci Health. 1(4):206–220.

- White WL, Campbell MD, Spencer RD, Hoffman HA, Crissman B, DuPont RL. 2014. Patterns of abstinence or continued drug use among methadone maintenance patients and their relation to treatment retention. J Psychoactive Drugs. 46(2):114–122.

- World Health Statistics. 2022. Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Willig C. 2019. What can qualitative psychology contribute to psychological knowledge? Psychol Methods. 24(6):796–804.

- Wisdom JP, Cavaleri M, Gogel L, Nacht M. 2011. Barriers and facilitators to adolescent drug treatment: youth, family, and staff reports. Addict Res Theory. 19(2):179–188.

- Zuffa G, Meringolo P, Petrini F. 2014. Cocaine users and self-regulation mechanisms. Drug Alcoh Today. 14(4):194–206.