ABSTRACT

In recent years recreation, sport and even children’s play have been affected and, in some ways, transformed by safety concerns. Although safety is a desirable goal, it may at times impinge on personal freedoms and the contribution of these activities to health and wellbeing, and it follows that a balance needs to be struck between safety and these other sought-for goals. A difficulty has been that safety concerns are usually addressed by carrying out a risk assessment, but, so far as the commonly used methods are concerned, the benefits of an activity are not part of this process and may be undervalued or forgotten. One solution has been to go beyond conventional risk assessment to a procedure that includes consideration of benefits. However, it is fair to say that this has been a slow process, partly because it appears novel and challenging, but this essay posits that benefit-risk assessment is not a newly invented procedure but one that has been commonplace throughout history, and that only from a narrow perspective can it be considered novel. The essay goes on to discuss aspects of the benefit-risk process including its historical roots, research insights, and implications for leisure time decision-making.

1. Introduction

In recreation and sport higher-risk activities such as skiing, rock climbing and contact sports endure only because the dangers involved are perceived as acceptable in exchange for the enjoyment or benefits which they bring (Adams, Citation1995; Starr, Citation1969). The same applies to numerous lower risk leisure activities such as trekking, sightseeing, outdoor skills education, and visiting a playground (Brussoni et al., Citation2012; Cottrell & Cottrell, Citation2020; Visitor Safety Group, Citation2020).

In recent decades, the need to be more transparent about this trade-off between risk of injury and benefits has come about because of the reconfiguration of the risk agenda, in which risk of accidental harm began to dominate peoples’ concerns. This may have been fuelled by what sociologists refer to as the “culture of fear” (Furedi, Citation2006) or the notion of the “risk society” (Beck, Citation1992) – the belief that contemporary society is increasingly preoccupied with insecurity about current and future risks, irrespective of the actual level of threat or, one might add, the emergence of an unreal expectation of a risk-free life.

This growing focus on risk of injury began to impinge on benefits, which tended to be ignored or take second place. For example, in a much-cited legal case in England, involving a swimming accident in a lake, Lord Hoffmann found it necessary to emphasize the social value of the activity which gave rise to the risk which had otherwise been forgotten (House of Lords, Citation2002, para. 34).

The following essay describes the background to this dilemma and the evolution of benefit-risk assessment (B-RA) as an approach for restoring social benefits to the agenda. The account is primarily from a U.K. perspective although similar issues have been noted in other modern industrial countries. Multidisciplinary research which supports and elucidates the B-RA process is also described.

2. Recent history

Arguably the recent history of B-RA has been presaged by a shift in the way accidents are perceived and recorded. The sociologist Judith Green (Citation1997) has described how, in the last half century, there has been an increasing awareness of accidents as causes of death and disability, but not until the 1950s did policy makers or the medical profession begin to show much interest in studying their causes or investigating their prevention. By the 1960s, however, accidental injuries began to be recognized as a legitimate public health concern in Britain and the U.S.A., with the medical profession opting to treat it as a disease. This soon led to the professionalization of accident prevention, resulting in the formation and expansion of many agencies whose focus was accidents. The professional concern over accidents increased such that in 2001 an editorial in the British Medical Journal proposed that the word “accident” be banished (BMJ, Citation2001). The implication was that all injury events were foreseeable and could, with sufficient care, be prevented.

In the U.K., the passage of its Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 (HSWA) also strengthened legal requirements to manage safety risks. While this might appear to be separate from leisure and recreation, the wording of Section 3 of the Act is such that persons affected by work activities are also drawn under its umbrella. Therefore, according to the way in which this is interpreted, persons running a sport or leisure activity such as, say, a country park, may be liable for the safety of participants and visitors. In the extreme, a toddler playing in the park sandpit is covered by the HSWA.

It shall be the duty of every employer to conduct his undertaking in such a way as to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that persons not in his employment who may be affected thereby are not thereby exposed to risks to their health or safety. (HSWA, 1974, Section 3, part of; National Archives, Citation2021)

By the 1990s, however, it was dawning that the pursuit of safety could have negative consequences if it in some way deterred people from taking part in leisure activities. In addition, concern over the legal liability of providers of leisure and recreational opportunities was mounting because of its impact on leisure provision. This led in 2006 to the U.K. government reacting by passing The Compensation Act. This stated, among other things, that:

A court considering a claim in negligence or breach of statutory duty may, in determining whether the defendant should have taken particular steps to meet a standard of care (whether by taking precautions against a risk or otherwise), have regard to whether a requirement to take those steps might:

(a) prevent a desirable activity from being undertaken at all, to a particular extent or in a particular way, or

(b) discourage persons from undertaking functions in connection with a desirable activity. (National Archives, Citation2021)

Also, in response to the pressure, several industry bodies were formed. In particular, the U.K. Play Safety ForumFootnote1 was created in 1993 with the objective of promoting play, including a balanced approach to risk within play provision. Other sectoral groups addressed additional factors such as the benefits of natural ecosystems and the authenticity of historic sites which could have been compromised by safety interventions. For example, the U.K.’s Visitor Safety Group,Footnote2 the National Tree Safety Group,Footnote3 and the English Outdoor CouncilFootnote4 published their own guidance. Interests included a balanced approach to the management of associated risks and benefits (Ball & Ball-King, Citation2013).

What was to some extent lacking at that time was research evidence on the benefits of recreation. This started to emerge by the 1980s and would go on to lead the pioneering Scottish epidemiologist Jerry Morris to refer to exercise as “the best buy in public health” (Morris, Citation1994). This prompted calls for investment in getting people more active to both improve the nation’s health and deliver substantial savings for the health service. The growing body of research highlighting the impressive health benefits of leisure activity (e.g. Mannell, Citation2011) now extended to contact with nature as another essential part of a healthy life (Donovan et al., Citation2015; van den Bosch & Bird, Citation2018; Warburton et al., Citation2006).

In later years, this message has been taken up by major bodies including the British Medical Association (BMA, Citation2019) and the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2017), who similarly identified physical activity as one of its “best buy” health interventions for policymakers on grounds of cost-effectiveness and feasibility.

In the early 2000s, the spotlight on health shifted to children and their recreation. Emerging research suggested that the quest for ever-greater levels of safety and injury prevention was limiting children’s play opportunities, and in so doing hampering their development (Ball et al., Citation2019; Brussoni et al., Citation2012) and was potentially linked with increases in obesity (Public Health England, Citation2017). Mounting evidence revealed the physical and emotional benefits of children’s play (Gill, Citation2014) including “risky play” in physically stimulating and challenging outdoor environments – and yet trends indicated that this was in decline (Sandseter, Citation2007).

3. B-RA and cost–benefit analysis

The preceding account makes clear the need to recognize that there is a trade-off between benefits and risks. A trade-off can be defined as:

A situation in which you balance two opposing situations or qualities: There is a trade-off between doing the job accurately and doing it quickly. She said that she'd had to make a trade-off between her job and her family. (Cambridge English Dictionary, Citation2021)

Achieving recognition for the legitimacy of this trade-off in the leisure sector has been a slow process. This is partly because injury prevention is clearly a virtuous cause and, when a bad accident occurs, this is recalled. In the U.K., the way in which the HSWA has sometimes been interpreted has also led to problems. The Act says that persons responsible for some hazardous situation or activity must do everything that is reasonably practicable to reduce the likelihood of it happening. The term reasonably practicable refers to a trade-off – but one between the benefit of a control measure (i.e. the amount of risk reduction it brings about) and the cost and difficulty of implementing the measure. As such, it is silent regarding the trade-off of interest here, which is between the benefits of some activity and its risks (see and for examples of these types of trade-off). This is likely because the HSWA is mainly about industrial and workplace safety in which these wider, non-safety benefits, are not usually relevant. However, it is encouraging to note that the U.K.’s principal safety regulator, the Health and Safety Executive, gave its support to the concept of B-RA in 2012 when it wrote, in the context of children’s play:

Key message: Play is great for children’s well-being and development. When planning and providing play opportunities, the goal is not to eliminate risk, but to weigh up the risks and benefits. No child will learn about risk if they are wrapped in cotton wool. (HSE, Citation2012, p. 1)

Figure 1. This shows an obvious risk of death or serious injury through falling onto the track as there is no track-side barrier. The trade-off in this case is between the risk of injury and the cost and difficulty of control.

Figure 2. The footpath along the Beachy Head cliffs is mostly unfenced despite a drop rising to over 150 m. The trade-off here is between the risk of falling and the desire to preserve an attraction in its natural state.

In government, the need for trade-offs is widely recognized and cost–benefit analysis (CBA) is a much-used decision-aiding tool for assessing the economic viability of projects. It is also used to assess new regulatory interventions, where it is referred to as Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) (HM Treasury, Citation2018). CBA and RIA seek to value the costs and benefits of alternative options with the aim of choosing the best option, which is normally the one with the highest net present value (NPV). The NPV is the difference between the value of the benefits and the costs. As costs tend to be incurred up front and benefits usually accrue in the future, a discount rate is normally applied to the benefit stream, hence the term NPV.

CBA can also be applied in circumstances where health or safety interventions are being considered. The cost of a new risk control or health improvement measure is relatively easy to determine. More difficult is putting a value on the benefits. These might be improved health in the population, or a reduced risk of injury or death in, for example, a workplace setting. However, techniques exist for valuing health gains and reduced risks (Ball & Ball-King, Citation2014) so the process is like that described above.

It can be seen from this that B-RA and CBA have much in common. B-RA is about the trade-off between the benefits of a thing, place or activity and its associated risks of harm. CBA, when applied to healthcare or industrial safety, is about the trade-off between the benefits of the measure (improved health or lower risk of harm) and its cost, as summarized in .

Table 1. Comparison of B-RA and CBA.

4. Theory of B-RA

A theoretical basis for B-RA can be drawn from the field of decision science, which studies the types of decision rules people use when they make a choice. Two such prominent classes are what are known as compensatory and non-compensatory decision rules (Yoon & Hwang, Citation1995). Under a compensatory strategy, positive and negative attributes of different alternatives can be tallied and traded off against each other to reach a decision. For example, do any of the alternatives have a positive NPV, and can the ones that do be ranked according to the magnitude of the NPV?

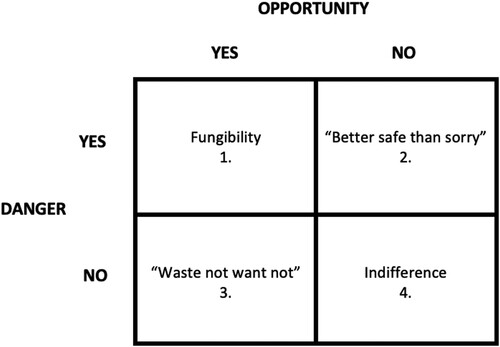

Non-compensatory strategies, on the other hand, ignore trade-offs. If a given attribute falls below a certain cut-off point, the option is eliminated, regardless of superior scores in other areas. As such, non-compensatory strategies are more straightforward and require less information but may result in less optimal decisions (Beach & Mitchell, Citation1978; Gigerenzer & Todd, Citation1999). gives examples of the two approaches.

Table 2. Examples of a compensatory and non-compensatory decision.

When applied to safety, compensatory approaches align with the notion that safety is not the only consideration in decision-making. Other things of value could include well-being, conservation of cultural heritage, and all those things that constitute “natural capital” (DEFRA, Citation2020). According to HM Treasury:

Natural capital includes certain stocks of the elements of nature that have value to society, such as forests, fisheries, rivers, biodiversity, land and minerals. Natural capital includes both the living and non-living aspects of ecosystems. Stocks of natural capital provide flows of environmental or “ecosystem” services over time. These services, often in combination with other forms of capital (human, produced and social) produce a wide range of benefits. These include use values that involve interaction with the resource and which can have a market value (minerals, timber, freshwater) or non-market value (such as outdoor recreation, landscape amenity). (HM Treasury, Citation2018, p. 45).

However, the existence of alternative approaches to safety which aim to minimize risk or even seek zero harm, e.g. see debate pro and con tree-lined routes (Treework Environmental Practice, Citation2015), demonstrates that compensatory approaches are not universally recognized by the broader safety community. The reason for this will be discussed below.

5. Recognition and understanding of B-RA today

As has been noted, the use of B-RA (and CBA) today is exceedingly common although often not recognized for what it is. It is observable across an array of sectors ranging from healthcare and aviation to leisure and children’s play (Ball-King, Citation2020; ICAO, Citation2013; NICE, Citation2013; Play Safety Forum, Citation2014).

In the medical sector, new health technologies are authorized only if the benefit-risk assessment shows a sufficient positive “benefit-risk balance” based on the scientific evidence (Curtin & Schulz, Citation2011). The evaluation has historically been done semi-quantitatively, with a separate consideration of the data sets on risks and benefits, usually derived from randomized controlled trials (Yang et al., Citation2010). The joint consideration of various risks and benefits has historically relied on value judgments informed by clinical expert opinion (Mühlbacher et al., Citation2016).

The Danish safety expert, Erik Hollnagel, characterizes another type of trade-off in industry, which he terms the efficiency-thoroughness trade-off (ETTO) (Hollnagel, Citation2009). The ETTO often takes the form of a relationship between how fast something can be done, and how precisely it can be done. It applies to individuals and organizations. Consider, for example, a radar operator trying to identify an approaching object as friend or foe – an incorrect identification might be fatal, but so might waiting too long in order to be sure. Since it is rarely possible to be both thorough and efficient at the same time, usually one is sacrificed for the other.

The American commentators Graham and Wiener approach the issue from a different angle; that of unrecognized trade-offs (Graham & Wiener, Citation1995). Looking across health, safety and environment, they find that all too often, costly interventions aimed at targeting one risk inadvertently generate a set of new, countervailing risks. For example, aspirin alleviates headaches but irritates the stomach, just as the Formula 1 “halo” titanium surround protects drivers from flying debris but lies directly within their line of vision. Such trade-offs are omnipresent and can quietly hinder risk reduction efforts. Whilst in many cases they are inevitable, the authors contend that we could face them far more effectively.

For Graham and Wiener, the problem of unrecognized risk trade-offs arises from a number of systematic shortcomings in the way decisions are considered and formed. One such powerful source is the increasing fragmentation of roles. They refer to the U.S. health service and the splintering of medical care into ever-smaller specializations. Whilst this brings certain advantages, it has also drawn criticism for creating a growing oversupply of specialist physicians, and an undersupply of generalists. In short, a medical system less capable of treating “whole patients”. They observe that this fragmentation of roles is similarly rampant in (U.S.) government. This chimes with other commentators who have similarly noted a growth in bounded roles (Gawande, Citation2009; Krier & Brownstein, Citation1992), leading to a failure to treat risk in a coordinated way.

A further prominent source of unrecognized trade-offs is what the authors term the “omitted voice” – the absence of affected parties from the decision process and the accompanying disproportionate influence of more powerful organized interests. In relation to B-RA, the omitted voice phenomenon is perhaps also apparent in the supplanting of the frontline experience of duty holders by protocols, codes of practice and standards. It is this failure to consider “the whole patient” which is arguably the chief weakness of risk assessments that are too narrowly constructed.

To remedy the situation, Graham and Wiener propose a move away from the narrow decision-making and piecemeal regulation they see as widespread. They advocate instead for a more systematic, holistic approach to decision-making with efforts to treat risks made not in isolation but in the context of the larger picture. Such an approach would be better equipped to “treat the whole patient”.

A source of related ideas is provided by the American economist, Howard Margolis (Citation1996), who, like Graham and Wiener, examined why decision-makers may fail to recognize trade-offs. To explain this Margolis introduces the concept of “fungibility” – one’s ability to consider the full panoply of trade-offs when faced with a risk decision. He presents the following matrix of risk trade-off scenarios ().

Figure 3. Margolis’ categorization of decisions which recognize or not (a) danger of harm and (b) opportunity costs of controlling the harm (Margolis, Citation1996).

Margolis argues that rifts in approaches to risk decision-making arise because different persons occupy “polarized” states. It could be said, for instance, that those who seek to maximize safety would subscribe to the adage “better safe than sorry”. Conversely, unless a safety measure averts some meaningful risk, most would not logically want to incur the cost or inconvenience, as illustrated by the adage “waste not want not”.

The ideal scenario, he contends, is that situated in cell 1. This context is characterized by fungibility. Here, one is alert to both the costs that go with the risk and the costs of taking precautions against that risk; in other words, one can trade-off the advantages of caution against those of boldness.

6. Understanding opposition to B-RA

It is apparent that B-RA may be overlooked or even rejected by some parties. Single-issue campaigns and advocacy groups, for example, by their nature do not take account of matters they see as peripheral, but which may be impacted by their actions. As Graham and Wiener (Citation1995) note, they may even suppress discussion of the countervailing risks of proposed policies. For instance, the felling of roadside trees for Passive Safety (Treework Environmental Practice, Citation2015), or the Vision Zero movement (Citation1994) which aims for the elimination of fatalities and serious injuries on roads, both have knock-on consequences including generation of countervailing risks. The first, for example, has obvious environmental impacts, and may not be as effective as hoped as drivers are known to take more care when obvious hazards are present (Adams, Citation1995). The second raises questions of practicability and proportion – is this the most efficient use of resources (Elvik, Citation2001)?

The social scientist David Seedhouse offers an explanation as to why opposition might arise in the form of his “Rational Field Theory” (RFT) (Seedhouse, Citation2020). He notes that we have become accustomed to thinking of ourselves as fully rational beings, capable of making unbiased, evidence-based decisions. However, the reality is that we organize the world around ourselves according to numerous conventions:

It is beyond doubt that evidence must be framed by human speculations, classifications, drives and instincts, social environment and history, and our personal preferences or values. (Seedhouse, Citation2020, p. 63)

This array of internal and external forces compromises our “rational field”, and drives the choices we make, often unknowingly. Seedhouse illustrates this by observing that decisions described as “science-led” frequently rely on models that are based on small pieces of evidence and extrapolated, to great uncertainty.

For Seedhouse, RFT explains the existence of single-minded approaches to decision-making that he sees in abundance across society. It reveals why different individuals favour one set of logic and evidence over another. In relation to B-RA, it could explain why some people do not even think of, or are opposed to, compensatory decision-making.

As with the theory of Graham and Wiener (Citation1995), Seedhouse proposes a remedy based on awareness of the big picture. RFT offers the prospect of elucidating beliefs, values and other factors in decision-making, in order to move towards being able to judge between our rational fields comprehensively. Once understood, rational fields enable better decisions using evidence and values in their proper balance.

Earlier it was stated that the shift to a compensatory decision approach in the sectors under discussion has been a slow process. This can be understood because society has been moving to an era of explicit rules, guidance, and codes of practice for everything (Gascoigne & Thornton, Citation2014; Power, Citation2004). Such guidance is only as good as the vision of its authors and tends to take a narrow view of what is sought. Only recently have the potential shortcomings of this approach been realized and moves taken to turn the tide.

7. How can B-RA be done?

Turning to the practicalities of carrying out B-RA, a key consideration is that, as with risk assessment, it can in theory be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative risk assessment is well-established in sectors such as environmental pollution and radiological protection, where dose–response relationships are reasonably well understood, and in national industries such as offshore, nuclear and transportation where historical accident data are available so that risk can be reliably assessed (Ball, Citation2005).

However, in leisure, and public life in general, the process is largely qualitative. This is mainly because while there is research on the linkage between leisure and health, the benefits accrue slowly, and it has to be maintained over a period of time. This renders benefits problematic to measure quantitatively.

Typical tools for assessing risk are described in ISO 31010 (CENELEC, Citation2009), which contains over 30 different risk assessment techniques. These range from qualitative techniques such as brainstorming and checklists, to semi-quantitative tools such as cost–benefit analysis, Hazard and Operability studies (HAZOP) to matrices and decision trees, to fully quantitative aids using F-N curves and Bayesian statistics. The fact that B-RA does not feature in the standard suggests that, despite its extensive history of usage, it was overlooked by the authors, possibly because their background worldview was industrial, rather than health, leisure or environmental protection.

Guidance on how B-RA might be conducted emanates from the authors Seedhouse and Peutherer (Citation2020). Writing in relation to health and social care, they observe that rules and algorithms have come to usurp the personal judgment of practitioners and, in so doing, hampered their ability to provide care in a responsive and effective manner. What is needed above all, they contend, is the restoration of personal judgment in decision-making.

For Seedhouse and Peutherer (Citation2020), a system in thrall to protocols and rule-following falters because it belies the messy, complex nature of reality. Personal judgment is indispensable when dealing with the innumerable uncertainties inherent in decisions. Far from the common perception of being detached and objective, decision-makers, like all people, are inextricably linked to and shaped by their environment. Furthermore, most decision-making happens unconsciously and almost instantly. This means that it is both impossible and undesirable to attempt to make decisions that might be considered strictly evidence-based, for the evidence itself requires personal interpretation.

Linked to the above is an incredibly longstanding debate, traceable to Plato, over the merits of experts’ judgments as opposed to explicit rules-based logic. Gascoigne and Thornton (Citation2014) identify a millennia-old suspicion of knowledge that cannot be put into words or directly rendered as a logical proposition. In the modern era, this manifests itself through “systematisation” – the growing inclination towards explicit rules, guidelines, benchmarks and league tables (Power, Citation1996, Citation2004). Such reforms aim to replace tacit or implicit understandings of practices with something explicit and codified, and in so doing obviate dependence on the skilful judgments of individuals. Underlying this is the belief that codification is linked to objectivity, and that tacit forms of judgment can be “cleansed” of subjective factors in this way.

In tune with the thinking of Seedhouse, Hollnagel (Citation2017) observes that people do not act on what they can see, but rather on what they perceive. These perceptions are based on “multiple and sometimes conflicting interests and motivations and are rarely if ever in agreement with the ideal of rational decisions”. As Seedhouse and Peutherer posit: “If health workers are intelligent, caring, responsible and well educated, do they really need to be told so extensively how to behave?” (Citation2020, p. xv).

The conclusion that can be drawn is that B-RA is not something that can be done quantitatively in practical circumstances. Parts of the process may be quantifiable, but rarely all, and the point at which a decision is made about the balance between benefits and risk will necessarily remain subjective – a judgment – because it involves not only scientific data but human values. Organizations such as the Play Safety Forum (Citation2014) and Outdoor Play Canada (Citation2019) have therefore stated that B-RA should be descriptive and not quantitative in form.

8. Who is best placed to do B-RA?

In certain situations where causal relationships are clear and established, or where an issue is purely technical and straightforward (e.g. designing out head trap hazards on babies’ cots), decision-making can proceed almost exclusively via scientific analysis. However, it has been noted that the arena of public life is volatile and complex. It can even be described as a Complex Adaptive System (Holland, Citation2014), which has been defined as a system in which interaction between multiple agents leads to adaptation and self-organization, such that outcomes are not readily predictable.

For example, the outcome of safety interventions in leisure is affected by the response of recipients, which may include risk compensatory behaviour, i.e. persons may change their behaviour and thus enhance or undermine the effectiveness of the intervention (Adams, Citation1995). An example of this might be the current trend in towns and cities to introduce “shared space” schemes whereby pedestrians and traffic occupy the same location without barriers. The theory is that in a more ambiguous environment both drivers and pedestrians will exercise more care, so reducing the accident rate. As yet, there is no way of reliably predicting the outcome of such interventions, and the only way to evaluate them is by experimentation and monitoring.

This means that it is seldom possible to proceed with such an approach without considerable uncertainty. In addition, it has been well documented that humans, when faced with a complex problem, revert to mental shortcuts or heuristics based on their accumulated experience and knowledge (Gigerenzer & Todd, Citation1999; Kahneman et al., Citation1982). This reliance on experience-based heuristics is seen to have strong and weak points as far as decision-making is concerned and has been debated, notably by Kahneman and Klein (Citation2009).

Thus, whilst Kahneman has written extensively on the way heuristics reveal themselves as cognitive biases and lead to flawed decision-making, Klein instead marvels at the successes of intuitive judgments. After analysing the way in which firefighters can make effective decisions under extreme, adverse conditions, he developed the concept of Naturalistic Decision-Making (NDM). NDM looks at decision-making in challenging real-world settings, particularly situations of complexity, uncertainty, time pressure and changing conditions. It describes how people use their experiences to amass, over time, a mental repository of patterns. When rapid decisions are needed, people can intuitively and fluidly match the current situation to the patterns they have learned and experienced in the past, and act accordingly. As such, NDM requires expertise to accumulate a sufficiently large pool of mental patterns. Other commentators, such as Gigerenzer and Todd (Citation1999), have similarly questioned the view that heuristics produce flawed decisions, arguing instead that they can be used to make “fast and frugal” judgments that are both efficient and accurate.

Underlying the NDM field of decision-making is the premise that intuition relies heavily on what is known as tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is the knowledge we possess, garnered from personal experience and lifelong learning, that is difficult to articulate, or transfer between persons. As the authors Collins and Evans (Citation2007) note, this form of knowledge is ubiquitous yet commonly resides at the subconscious level of habits and intuition. Throwing and catching a ball, recognizing a face, or learning a language may all fit this criterion. Within leisure and recreation, tacit knowledge is perhaps most notably invoked in relation to rapid changes in weather for activities such as skiing, climbing or sailing. Experienced instructors, for example, can instinctively and dynamically gauge the risks of a changing environment without necessarily being able to fully explain how.

Collins and Evans develop a scale of tacit knowledge, and term its highest form “contributory expertise”, proposing that it is acquired through immersion within a sector. As Klein (Citation2015) likewise observes, immersion is essential for acquiring a broad experience base. Contributory expertise ultimately enables one to carry out an activity with competence, and to contribute to a domain of practice. Thus, it appears that in leisure and public life, this is likely the first port of call for risk-benefit decision-making.

The above lends weight to the proposition that those best placed to do B-RA are those who inhabit most closely the place or activity that is taking place, and so, in the thinking of Seedhouse and RFT, are in the relevant “frame”. They have the greatest knowledge of local circumstances, over and above any external actors or inspectors who are normally present only for short periods.

This resonates with the situation in the U.K., whereby duty holders are conferred a special status due to the deeply embedded principle of self-regulation, and the associated notion that “duty holders know best” about how to manage risks.

9. A definition of B-RA

As this essay concludes, it is appropriate to provide a potential definition of benefit-risk assessment. Three are offered here:

B-RA is a form of risk assessment that considers both risks and benefits in parallel when making decisions. It is a balanced approach that involves judgment and therefore needs to be based on clear values and understandings. Where appropriate it takes into account local circumstances.

B-RA is a form of decision-making that compares (trades-off) risks of harm associated with space and activities against their benefits, and then decides, on balance, whether to go ahead, or to make changes to the balance or not to proceed.

B-RA is a form of risk assessment that considers both risks and benefits in parallel when making decisions. It is a balanced approach that involves judgment and therefore needs to be based on clear values and understandings. It takes into account local circumstances and in most circumstances can only realistically be done descriptively.

10. Concluding remarks

As this essay has described, far-from being a radical development, B-RA is in fact a deeply entrenched, mature approach to decision-making. It reflects the fact that in many or even most contexts, decision-making is complex and multi-faceted in nature, and therefore cannot be resolved by focusing on any one objective (Hammond et al., Citation1999). This is particularly true in the case of leisure, recreation, play and public safety where organizers of activities cannot avoid factoring social utility into their decisions, rendering trade-offs inescapable.

The sociologist Ortwin Renn (Citation2020) has observed that in the public realm, decision-makers have often been shy in admitting they have made trade-offs and tolerated some bad outcome in exchange for a positive one. This gives the illusion that there is always a win-win situation – but for Renn, it is a false proposition that is often unhelpful.

Further, B-RA has solid theoretical roots in the form of compensatory decision-making and is a well-established tool of decision science. Positive attributes in one dimension (benefits) can be traded-off against negative attributes in another (risks). The outcome is a broad, balanced approach to risk. The alternative, which does not consider trade-offs, is less demanding, but is prone to lead to poorer outcomes.

In summary, this essay arrives at the following positions:

benefit-risk assessment is no more than an adaptation of conventional compensatory decision processes that have been and continue to be widely used within society

benefit-risk assessment, whilst mature and widespread, is nonetheless conceptually distinct from conventional risk assessment and requires informed, nuanced considerations from the assessor to decide where the balance of risk and benefit lies in any particular case

the aim of benefit risk assessment is to restore balance (proportion) to decision-making in leisure, sport, recreation and public life

where scientific data are available to inform benefit-risk decision-making they should be used, but ultimately benefit-risk decisions will involve judgment because they involve human values

this implies that benefit-risk assessments are best described in narrative statements rather than as quasi-numeric outputs

In most circumstances, the persons best suited to making benefit-risk judgments will be “generalists”, that is, people with direct experience of both the benefits and the risks, and who have “contributory expertise”

Finally, it should be acknowledged that the content of any B-RA of a leisure activity will likely vary depending on the originator. For example, organizers of leisure activities, site operators and equipment manufacturers may be inclined to incorporate legal responsibilities, real or perceived, as in the case referred to in section 1 of this paper, whereas leisure participants are more likely to focus on the personal risks and benefits. However, the underlying message is that for all stakeholders, whether providers, organizers, intermediaries or users, benefits should be a key part of the equation. This accepts that users will be exposed to risk and appropriate notification should be provided such that they are able to make a reasoned choice on participation. In the case of children’s activities, exposure to some risk is still beneficial but requires additional control measures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The PSF includes representatives from the four UK nations (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), industry representatives, safety bodies and the HSE.

2 Members include British Waterways, Historic Scotland, English Heritage, the Forestry Commission, the Environment Agency, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the National Trust, Natural England, the Woodland Trust, the Peak District National Park, and the National Trust for Scotland.

3 Members include the Arboricultural Association, Ancient Tree Forum, the Tree Council, Confederation of Forest Industries, Forestry Commission, English Heritage, Royal Institution of Chartered Foresters, Institute of Chartered Foresters, National Trust, Woodland Trust, London Tree Officers Association, and the Country Land and Business Association.

4 EOC members include the Association of Heads of Outdoor Education Centres, British Activity Providers Association, Christian Camping International, Institute of Outdoor Learning, National Association of Field Study Officers, Outdoor Education Advisers’ Panel, Outdoor Industries Association, the Scout Association, and the Young Explorers’ Trust.

References

- Adams, J. (1995). Risk. UCL Press.

- Ball, D. J. (2005). Environmental health policy. Open University Press.

- Ball, D. J., & Ball-King, L. (2013). Safety management and public spaces: Restoring balance. Risk Analysis, 33(5), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01900.x

- Ball, D. J., & Ball-King, L. (2014). Public safety and risk assessment: Improving decision-making. Earthscan.

- Ball, D. J., Brussoni, M., Gill, T. R., Harbottle, H., & Spiegal, B. (2019). Avoiding a dystopian future for children's play. International Journal of Play, 18(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2019.1582844

- Ball-King, L. (2020). Risk management and proportionality: A synoptic view of UK practices [PhD thesis, King’s College London].

- Beach, L., & Mitchell, T. (1978). A contingency model for the selection of decision strategies. Academy of Management Review, 3(3), 439–449. https://doi.org/10.2307/257535

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage.

- British Medical Association. (2019). Get a move on: Steps to increase physical activity levels in the UK. https://www.bma.org.uk/what-we-do/population-health

- British Medical Journal. (2001). Accidents are not unpredictable. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1320

- Brussoni, M., Olsen, L., Pike, I., & Sleet, D. (2012). Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(9), 3134–3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9093134

- Cambridge English Dictionary. (2021). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/trade-off

- CENELEC. (2009). 31010 risk management – risk assessment techniques.

- Collins, H., & Evans, R. (2007). Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press.

- Cottrell, J. R., & Cottrell, S. P. (2020). Outdoor skills education: What are the benefits for health, learning and lifestyle? World Leisure Journal, 62(3), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2020.1798051

- Curtin, F., & Schulz, P. (2011). Assessing the benefit: Risk ratio of a drug-randomized and naturalistic evidence. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/fcurtin

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. (2020). Enabling a natural capital approach. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/869801/natural-capital-enca-guidance_2_March.pdf

- Donovan, G. H., Michael, Y. L., Demetrios, G., Prestemon, J. P., & Whitsel, E. A. (2015). Is tree loss associated with cardiovascular-disease risk in the women’s health initiative? A natural experiment. Health & Place, 36, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.08.007

- Elvik, R. (2001). Cost-benefit analysis of road safety measures: Applicability and controversies. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 33(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(00)00010-5

- Furedi, F. (2006). Culture of fear revisited. Continuum Press.

- Gascoigne, N., & Thornton, D. (2014). Tacit knowledge. Routledge.

- Gawande, A. (2009). The checklist manifesto: How to get things right. Metropolitan Books.

- Gigerenzer, G., & Todd, P. (1999). Simple heuristics that make US smart. Oxford University Press.

- Gill, T. (2014). The play return: A review of the wider impact of play initiatives. ISBN 178-0-9556647-9-3. http://www.playscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Play-Return-A-review-of-the-wider-impact-of-play-initiatives1.pdf

- Graham, J., & Wiener, J. (1995). Risk versus risk: Tradeoffs in protecting health and the environment. Harvard University Press.

- Green, J. (1997). Risk and misfortune: The social construction of accidents (pp. 96–97). UCL Press.

- Hammond, J., Keeney, R., & Raiffa, H. (1999). Smart choices: A practical guide to making better decisions. Harvard Business School Press.

- Health and Safety Executive. (2012). Children’s play and leisure: promoting a balanced approach. https://www.hse.gov.uk/entertainment/childrens-play-july-2012.pdf

- Her Majesty’s Treasury. (2018). The green book – evaluation and appraisal in central government. TSO.

- Holland, J. H. (2014). Complexity: A very short introduction. OUP.

- Hollnagel, E. (2009). The ETTO principle. Ashgate.

- Hollnagel, E. (2017). Safety-II in practice. Developing the resilience potentials. Routledge.

- House of Lords. (2002). Tomlinson v Congleton Borough Council and others. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200203/ldjudgmt/jd030731/tomlin-1.htm

- International Civil Aviation Authority. (2013). Safety management manual. ICAO.

- Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. American Psychologist, 64(6), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016755

- Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press.

- Klein, G. (2015). A naturalistic decision-making perspective on studying intuitive decision-making. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(3), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.07.001

- Krier, J. E., & Brownstein, M. (1992). On integrated pollution control. Environmental Law, 22(1), 119–138.

- Mannell, R. C. (2011). Leisure, health and well-being. World Leisure Journal, 49(3), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2007.9674499

- Margolis, H. (1996). Dealing with risk: Why the public and the experts disagree on environmental issues. University of Chicago Press.

- Morris, J. (1994). Exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease: Today’s best buy in public health. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 26(7), 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199407000-00001

- Mühlbacher, A., Juhnke, C., Beyer, A., & Garner, S. (2016). Patient-focused benefit-risk analysis to inform regulatory decisions. The European Union Perspective, Value in Health, 19(6), 734–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.006

- National Archives. (2021). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/37/contents

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). How NICE measures value for money in relation to public health interventions. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/guidance/LGB10-Briefing-20150126.pdf

- Outdoor Play Canada. (2019). Risk benefit assessment for outdoor play: A Canadian toolkit. https://www.outdoorplaycanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/risk-benefit-assessment-for-outdoor-play-a-canadian-toolkit.pdf

- Play Safety Forum. (2014). Risk benefit assessment – worked example. https://psf-risk-benefit-assessment-form-worked-example.pdf

- Power, M. (1996). The audit explosion. DEMOS.

- Power, M. (2004). The risk management of everything: Rethinking the politics of uncertainty. DEMOS.

- Public Health England. (2017). Health matters: Obesity and the food environment. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment-2

- Renn, O. (2020). Inclusive risk governance. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lnPbpiZ0DLw&t=185s

- Sandseter, E. (2007). Categorising risky play – how can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930701321733

- Seedhouse, D. (2020). The case for democracy in the COVID-19 pandemic. Sage.

- Seedhouse, D., & Peutherer, V. (2020). Using personal judgment in nursing and healthcare. Sage.

- Starr, C. (1969). Social benefits versus technological risk. Science, 165(3899), 1232–1238. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.165.3899.1232

- Treework Environmental Practice. (2015). Tree-lined routes and the linear forest: A new vision of connected landscapes. Seminar 20 at Kew. http://treeworks-seminars.co.uk/resources/2015/12/27/tree-lined-routes-the-linear-forest

- van den Bosch, M., & Bird, W. (2018). Oxford textbook of nature and public health. OUP.

- Vision Zero. (1994). http://www.welivevisionzero.com/vision-zero/

- Visitor Safety Group. (2020). Managing visitor safety in the countryside. www.visitorsafety.group

- Warburton, D., Nicol, C., & Bredin, S. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(6), 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351

- World Health Organisation. (2017). Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. https://www.uicc.org/sites/main/files/atoms/files/WHO_Appendix_BestBuys_LS.pdf

- Yang, W., Zilov, A., Soewondo, P., Bech, O., Sekkal, F., & Home, P. (2010). Observational studies: Going beyond the boundaries of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 88, S3–S9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8227(10)70002-4

- Yoon, K., & Hwang, C. (1995). Multiple attribute decision-making. Sage.