ABSTRACT

Aim

The study was aimed to assess whether leisure learners who engage in Torah/Bible studies report higher levels of spirituality than those who study other subjects, and whether higher levels of spirituality result in a higher meaning in life and greater psychosocial resources, specifically hope and quality of life.

Methods

A survey of 234 participants, who study either Torah or other subjects in their leisure time. Participants completed self–report questionnaires to report their spiritual sources of motivation, features of the subject of study, evaluations of their learning experience, and their meaning in life, hope, and quality of life.

Results

Quantitative measures showed that higher quality of life among Torah learners was affected by meaning in life and by personal spirituality and hope, but was not affected by faith in God. Among non–Torah learners, personal spirituality and hope had stronger associations with quality of life and weaker associations with meaning in life, compared to Torah learners.

Conclusions

Torah and other subject of study had different effects on learners' psychosocial resources. This study emphasizes the importance of generalizing the findings of sources of spirituality on learning among formal students as well as different social behaviors between Torah and other enrichment learners.

In Western culture, leisure occupies a significant place in human life. At present, there is an abundance of leisure activities are available to in/ focuses on older adults who engage in Torah/Bible studies as a leisure activity. Torah studies inherently involve connecting with sacred and spiritual contents, exposure to ethical issues, and opportunities for philosophical and religious contemplation. Such a setting begs the question of whether engagement in Torah/Bible studies is associated with higher levels of spirituality and meaning in life.

In the present study we focused on adult learners approaching retirement who attend courses at their leisure in public institutions that cater for older leisure learners. One group of learners participated in Torah studies and the other studied other subjects. The study was based on several theoretical frameworks that suggest that leisure activities cultivate valuable psychological resources such as meaning, social support, and hope, and enhance positive emotions, thus increasing participants’ well-being (Newman et al., Citation2014).

The aim of the study was to assess whether learners who engage in Torah/Bible studies report higher levels of spirituality, resulting in higher meaning in life and other psychosocial resources, specifically hope and quality of life, compared to other leisure learners who study subjects that are unrelated to spiritual contents. Such differences, at least in part, may be due to the different contents and focus of the disciplines studied.

Literature review

There are many different conceptions of leisure: as time, as activity, as a state of consciousness, and as an important resource in human life (Davidovitch & Soen, Citation2016; Weber, Citation2010). Leisure is culturally dependent: Culture affects the type of leisure activities acceptable in a certain society (Weber, Citation2010), the quantity of time allocated to leisure, and the type and intensity of leisure activities (Soen & Rabinovich, Citation2011).

The association between leisure and quality of life has been studied for many years (Nehushtan, Citation1980). All studies on the benefits of leisure found a positive association between engagement in leisure activities and quality of life (Grant & Kluge, Citation2012; Heintzman & Patriquin, Citation2012). Research also found that leisure activities enhance self-esteem and sense of personal growth, and that leisure activities reduce the impact of adverse life events. Recent studies also found that spirituality is correlated with leisure, and is associated with hope, meaning in life, and quality of life among adult learners (Alkan et al., Citation2022).

In the past 20 years, the concept of aging has changed (Alkan et al., Citation2022) and has become more difficult to define: Who are we actually talking about: older adults? retirees? senior citizens? the elderly? These various definitions reflect society’s changing attitude toward members of this age. Generally, an older person is over the age of 65, but Western culture has a tendency to use this formal definition flexibly and apply it on a case-by-case basis. In addition to the aging of the population, which is expected to continue, the population of older adults is also become older: The percentage of adults over the age of 80 is increasing.

Erikson (Citation1950) defined old age as a developmental stage in human life in which individuals are given a choice of how to experience life – either by a sense of despair or by a sense of integrity.

Life expectancy in Israel is rated fourth-highest in the world. Recognizing the importance of addressing the older population, Israel established the Ministry of Senior Citizens, which became an important government ministry that exhibits creativity and initiates leisure activities for retirees. In addition, local governments develop and offer leisure and physical activities for senior citizens that encourage the latter to develop a routine activity. Community-based settings include socio-cultural social clubs for independent older adults, which offer leisure activities such as studies and lectures on various topics. More than 1,000 clubs nationwide are visited by approx. 40,000 senior citizens nationwide (Haught Citation2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic placed the population of older adults, both in the community and in assisted living facilities, at the center of risk and public attention. In response, governmental and municipal agencies as well as organizations that cater to older adults mobilized rapidly in order to assist this group (Berg-Weger & Morley, Citation2020).

The current study examined the associations that were formed between spirituality, meaning in life, and quality of life in adult men and women in Israel, both secular and religious, who choose to study either Torah studies or other subjects as a leisure activity.

Torah studies

Torah/Bible studies inherently involve connecting with sacred and spiritual contents, exposure to ethical issues, and opportunities for philosophical and religious contemplation. The universal relation to “the Other” is a significant component of such studies, as exemplified in the writings of the Jewish philosopher Levinas (Citation1981). Levinas’ philosophy prioritizes one’s responsibility toward the other person, an orientation that is linked to his intensive interpretation of the Talmud and scriptures (Epstein, Citation2001).

Studies indicate that the population of Torah students in Israel has changed over the past few decades and has become more diverse. Learner groups are now characterized by a different “profile” than in the past, and represent a broad socio-cultural cross-section of the population (Azulay, Citation2010; Ben-David, Citation2016; Bhabha, Citation2002; Sheleg, Citation2010). This new trend is attributed to a “revolution of Jewish renewal” (Bhabha, Citation2002; Sheleg, Citation2010) that was triggered the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin in 1995, due to the fracturing and trauma experienced by Israeli society, and crosses sectors and genders, embracing traditional and other contents and study methods. One development that reflects this change is the growing number of women who study Torah (Bar-El, Citation2009; Brown (Hoizman), Citation1996; Elor, Citation1998; Feuchtwanger, Citation2011; Halivni, Citation1997; Ross, Citation2007), although the percentage of women among Torah learners is still relatively low (Benjamin, Citation2019).

A shift in the motivation underlying Torah studies is also evident (Ben-David, Citation2016; Sheleg, Citation2010). At present, not only religious people study Torah as a religious precept, guided by the saying “And the study of the Torah is equal to them all” (Mishna, Tractate Peah 1:1), but rather a wider and more diverse public is studying Torah by choice, as a leisure activity that combines interest and pleasure, and constitutes a source of inspiration, enrichment, and spiritual uplifting (Davidovitch & Soen, Citation2016).

These new trends in Torah study, which are now studied by new groups of teachers and students using diverse discourse and study methods in a broad range of settings and times, challenge the traditional assumption that Torah study necessarily takes place in a yeshiva (Shenhav, Citation2001). Pluralist “batei midrash” (study centers) have been established, where Torah is learned as a leisure activity, such as Elul, Kolot, Alma, Bina, and an umbrella organization called Panim, which unites 60 organizations engaged in studying Jewish Israeli culture. These study centers attract a wide range of social groups who come together to study Torah.

From students in secular yeshivas in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the circle of students has grown to include Nahal groups and study groups abroad (Ben-David, Citation2016; Sheleg, Citation2010). These studies are part of dynamic identity-building processes taking place in Israel (Sheleg, Citation2010) and challenge the traditional division into sectors (Shenhav, Citation2001) and particularly the dichotomous “religious/secular” distinction (Ben-David, Citation2016; Sheleg, Citation2010).

The question is whether the choice of Torah studies as a leisure activity positively contributes to adult leisure learners’ heightened sense of spirituality, meaning in life, hope, and quality of life.

Meaning in life

Meaning in life is a philosophical term that refers to the reason and purpose of existence in general, and human existence in particular (Baumeister, Citation1991). Viktor Frankl, one of the prominent writers on this subject, suggested that humans are motivated by a “desire for meaning,” that is, a need to find meaning and purpose for one's in life. He viewed this need as the primary motivational force in humans (Frankl, Citation1969). Frankl characterized meaning as “something to be found rather than given” (p. 182). In his book “Man’s Search for Meaning,” Frankl (Citation1984) wrote that a person who has meaning can bear adversity more easily. Frankl saw frustration at a lack of meaning as the neurosis of the new era, caused by human socialization and the dissolution of traditions and religion. He claimed that if one fills one’s innermost recesses and finds meaning in life in some external cause to which he can direct himself, this will reveal his essence and resolve most of his neuroses.

Terror management theory, which deals with the importance of meaning in life, contends that there is a basic psychological conflict between the will to live and the knowledge that death is inevitable. in order to overcome the terror produced by this conflict, one needs a life of value and meaning (Greenberg et al., Citation1986). Terror management theory is based on the work of anthropologist Becker (Citation1973), who claimed that people are aware of their inevitable death and therefore require cultural structures to give their life value and meaning that is not transient. Many empirical findings in this field indicate that when people are aware of their mortality, they become more protective of their cultural values and self-esteem, and in this way moderate anxiety (Becker, Citation1973; Greenberg et al., Citation1986).

Meaning is frequently emphasized in theories of well-being. Researchers claim that finding meaning in life has significant implications for one’s will to live (Shmotkin & Shrira, Citation2012) and one’s ability to overcome a fear of death (Routledge & Juhl, Citation2010). Meaning in life plays an important role in moderating the negative effects of grave life events through restructuring and reappraisal, and can reinforce one’s wish to survive and improve one’s life and quality of life (Bronk, Citation2011; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014; Twenge von Humboldt et al., Citation2004).

Research results showed that meaning in life is positively correlated with overall Quality of Life scores, which include scores of emotional state, functional state, and physical state (Kreitler, Citation2016). Meaning in life is of special importance for the elderly. Although meaning in life is important for spirituality, spirituality is also connected to transcendent experiences of “a higher power,” “the sacred,” or “deepest reality” (4, 36–39), which may not be necessary to experience meaning in life.

The impact of leisure on meaning in life is important, due to the fact that leisure is a freely chosen, self-determined/independently motivated activity. Meaning can also be produced from one or multiple leisure activities. Leisure aims to maintain: (a) a joyful life, (b) a connected life, (c) a discovered life, (d) a composed life, and (e) an empowered life. Thus, these elements seem to represent distinct elements of meaningful engagement with life through leisure (Iwasaki, Citation2006).

Spirituality and meaning in life

Spirituality is a collective name for a variety of terms including purpose, soul, reward, retribution, karma, fate, God, or supreme power. Li and Lalani (Citation2020) recently stated that spirituality is an elusive concept and that the existing definitions and meanings of spirituality are too broad, abstract, and context dependent. In most studies, spirituality is defined through the main concept of the meaning and goals that one sets for oneself (Chiu et al., Citation2004). Several researchers focused on defining spirituality in terms of relationships with oneself and with others (Bowden, Citation1998). Others definitions include the desire to reach self-actualization (Fryback, Citation1993), satisfaction with life (Mickley et al., Citation1992); a desire for self-comprehension and inner balance (Astedt-Kurki, Citation1995); developing new perspectives regarding oneself, others, and a supreme power; a developmental process of expanding the boundaries of one’s self-concept (Batten & Oltjenbruns, Citation1999; Chiu et al., Citation2000; Reed, Citation1991).

Meaning in life calls for support of values or beliefs. Russo-Netzer and Elhai (Citation2015) claimed that in the current global and digital post-modern era, the disintegration of tradition and religious settings, and the absence of ethical anchors, generate uncertainty, instability, alienation, and loss of meaning. This support can be found in any dimension of spirituality (Russo-Netzer, Citation2020).

Murray and Zentner (Citation1989) defined spirituality as a dimension that exists in any person who strives to be in harmony with the universe, to find answers to queries regarding eternity and infinity, and who aims for meaning and mission, inspiration and wonder. Fallot (Citation2007) defined spirituality as an experience that contains elements of eternity, sanctity, and/or supreme values. Moreover, spirituality includes a special awareness or conception of life that strives for unity, integration, and wholeness. In light of these definitions, it appears that through spirituality, one gives eternal meaning to one’s experience of human existence (Kitrungrote & Cohen, Citation2006).

Spiritual beliefs have been found to play a vital role in helping older adults traverse life challenges. Spirituality in older adults is also associated with health and wellness and an increased coping ability (Hodge et al., Citation2010) and is considered an important correlate of successful aging (Hodge et al., Citation2010; Park et al., Citation2012; Roman et al., Citation2020). Moreover, studies have indicated a positive relationship between spirituality and gerotranscendence, especially in relation to the cosmic dimension (Braam et al., Citation2006; Melia, Citation2002). Gerotranscendence is the shift from focusing on materialistic and practical needs to a broader cosmic view, rethinking time and space, life and death, and the meaning of self, and aspiring to elevate faith and spirituality to a higher plane through a simpler lifestyle (Tornstam, Citation2005). A longitudinal study by Cowlishaw et al. (Citation2014) suggested that spirituality positively influences older adults’ perceptions of life experiences, thus impacting their overall sense of meaningfulness of life events. A study by von Twenge von Humboldt et al. (Citation2020) showed that spirituality gave meaning to life to elderly adult and helped them face adversities during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Hope

Hope is considered a protective factor that contributes to improved quality of life, both directly and indirectly via anxiety reduction (Mardhiyah et al., Citation2020). A common definition of hope is the aspiration for a better world and the perceived capability to derive pathways to achieve desired goals and motivate oneself via agency thinking to use those pathways (Snyder et al., Citation1991). It has been suggested that hope is a process that occurs throughout life by coping with various developmental tasks (Groopman, Citation2006). It is continuous and occurs both consciously and unconsciously, manifested in life transitions (Levi, Citation2013).

Research has focused on the relations between spirituality and hope, mainly in the context of religious spirituality (Ciarrocchi et al., Citation2008). However, questions on hope were also developed to help medical students and physicians to incorporate themes in a spiritual assessment (Anandarajah & Hight, Citation2001).

Judaism has a positive attitude to hope. In his classical article “Hope,” Menninger (Citation1959) states that despite tribulations, Jews are people of hope; They clung to the expectation that the Messiah would come and the world would become better. The Mishna and Talmud contain deep insights regarding the importance of hope in one’s life; Christianity, too, refers to hope as a virtue similar to charity and faith (Hopper, Citation2001), and perceives hope as a motivational force that leads to investing constructive efforts and sound expectations rather than unsound ones (Menninger, Citation1959).

Erikson's (Citation1950) stages of psychosocial development theory is one of the prominent models of the development of hope and its effects on behavior. According to Erikson, the first task of the “developing self” is to resolve the conflict between the sense of trust and the sense of mistrust. Successful resolution of this conflict instills in one not only trust in oneself and others but also hope (Miller & Thoresen, Citation2003).

Studies report negative associations between hope and anxiety and between hope and social alienation (Snyder, Citation2000; Snyder, Citation2000) and positive associations between hope and coping; Hope is meaningful for processes of resilience and recovery (Levi, Citation2013). Mature hope is realistic and independent, recognizing and accepting life’s difficulties, limitations, and finiteness (Frankl, Citation1984).

In Torah studies, students learn contents that involve departure, renewal, destruction, and revival (Bareli & Bar-On, Citation1999). Scholars appeared and who wrote the Mishna and Talmud included in their inscription expressions of hope and faith in continued life and in the good. Learning these contents might instill hope in the heart of those learning Torah as a leisure activity.

Quality of life

The World Health Organization defines quality of life as an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns (WHO, Citation2012).

For many years researchers in different domains have investigated the question, What is quality of life? (Alkan et al., Citation2022). A review of the literature on quality of life indicates that there is no consistent unequivocal definition (King et al., Citation1992). Some researchers use subjective measures based on the phenomenological approach, according to which quality of life is whatever a person perceives it to be (O’Boyle et al., Citation1994). Although this approach recognizes the environment’s impact on a person, it argues that the individual plays a key role in shaping their world. For this reason, much of the research that subscribes to this approach believes that an assessment of quality of life must focus on a person’s experiences rather than on their objective life circumstances (Keng & Hooi, Citation1995; O’Boyle et al., Citation1994) According to the definition of quality of life of other researchers, quality of life is determined by the gap between a person’s lifestyle and various references to which these are comparted such as future expectations, aspirations, needs, past experiences, the condition of others, and personal values (Keng & Hooi, Citation1995; Pavot & Diener, Citation1993).

Others view quality of life as the match between a person’s emotions and expectations (Andrew & Withey, Citation1976) or between a person’s emotional ties and social support and their personal attributes. Yet other studies incorporated additional measures such as aspects of self-esteem (Litwin, Citation2006).

Quality of life is a function of one’s cultural, social, and environmental setting (Diener et al., Citation1999). The dimensions of quality of life are determined on the basis of reports above a person’s perceptions and assessments of their life circumstances (Frytak, Citation2000). Some (Diener et al., Citation1999) consider quality of life to be associated with a person’s personality and internal emotions (DeNeve & Cooper, Citation1998), and to a lesser degree to their objective life circumstances (McCrae & Costa, Citation1994). It was also found that quality of life is stable (Lykken, Citation1999), and most people maintain a specific degree of quality of life (Schwarz & Strack, Citation1999) and they tend to readjust to their basic quality of life even if their live circumstances change (Diener & Diener, Citation1996; Cummins & Nistico, Citation2002).

On this foundation, two approaches to the assessment of quality of life emerged (Fredrickson, Citation2004). One, satisfaction with life, which represents a cognitive assessment of a person’s psychological adjust to life situations. The second approach claims that quality of life is related to personal growth, a search for meaning in life, and realization of one’s potential. This approach is considered to be multi-faceted, more complex, ambiguous, and difficult to measure. According to this approach, quality of life is an ongoing life process and not a final goal that can be evaluated.

Previous research has focused on the connection between quality of life and spirituality dimension. First, spiritual quality is one of the dimensions considered in quality of life health assessment (WHOQoL-SRPB, Group, Citation1998). Cherblanc et al. (Citation2021) found a connection between spirituality, religiosity, and quality of life, following previous research by Skevington and Böhnke (Citation2018).

Research hypotheses

Leisure learners of Torah and other subjects will show differences in measures of spirituality, hope, meaning in life and quality of life, such that these measures will be higher among Torah learners.

Significant positive correlations will be found between spirituality, hope, meaning in life, and quality of life.

Methodology

Sample

The research is based on a survey of 234 respondents over age 55, divided into two groups: a group of 106 Torah students (45.3% of the research respondents), and a comparison group of 128 leisure learners enrolled in lecture-based enrichment studies in non-Torah-related subjects (54.7%).

A comparison of the two groups found that there are significantly more males among Torah students, which is typical for the general population of Torah students. The groups did not differ in age (P = .5) as both groups consisted of older adults (which was the relevant population). With respect to family status, a higher percentage of Torah students were married, which is also typical for the general population of Torah learners. However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in education or economic status (see for more detailed data).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics, by group.

Measures

Spirituality

Spirituality was measured using a 20-item questionnaire adapted from Kreitler (Citation2016), including four factors, each represented by 5 items: regarding myself (personal), relating to others (communal), regarding the environment (nature), and regarding “God” (transcendental).

Hope

Hope was measured using the 12-item Hope questionnaire developed by Snyder et al. (Citation1991). Respondents rated their agreement on a scale from 1 (absolutely incorrect) to 8 (absolutely correct). Snyder et al. (Citation1991) report Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the Hope questionnaire in the range of .74 – .78. The questionnaire was translated into Hebrew by Dubrov (Citation2002). Levi (Citation2008) reported high reliability (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Meaning in life

In this study, meaning in life was defined as one’s sense of meaning, purpose, and mission (Hill et al., Citation2015) and was assessed by the 20-item Purpose in Life (PIL) questionnaire developed by Crumbaugh and Maholick (Citation1964). Participants rated their agreement with the items on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 7. Sample items include “I am usually bored” and “Life for me always seems routine and unstimulating.” The current study found high reliability, α = .92. The PIL score is the mean of the questionnaire’s items, such that higher scores reflect higher meaning in life.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using an instrument adapted from the short version of WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment subjective evaluation developed by the WHOQOL Group (Citation1998) and includes 26 items measuring four dimensions: physical health, psychological welfare, social relations, and surrounding. One item measures a general perception of quality of life. Participants rated their agreement with the items on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (totally agree). Amir et al. (Citation2005) reported a high reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α = .80).

Procedure

The study was approved by the Brookdale Institute, Kolot, and the Institutional Ethics Committee at Ariel University. Participants in lecture-style Torah studies and general enrichment courses were recruited from the Brookdale Institute at Bar-Ilan University, to whom 350 questionnaires were distributed between June 2019 and October 2020. At Brookdale Institute, people study various academic courses in their leisure time. Torah learners were recruited from Kolot, a pluralist organization that operates Torah study groups in Israel. All participants signed an informed consent form. Completed questionnaires were collected personally by the researcher during classes in these settings. Brookdale and Kolot students who preferred to complete the questionnaire online and submit the completed questionnaire by e-mail received a link to the questionnaire. None of the respondents were rejected by the researcher. Of the 350 questionnaires distributed, 43 were not completed in full and were therefore not included in the study, and 73 questionnaires were not returned (response rate of 67%).

The reliability of the measures is shown in .

Table 2. Reliability of measures.

Statistical analyses

In this research, the following SPSS tests were used; exploratory factor analysis, reliability tests, correlation tests and t-tests of differences of means. Path analyses were conducted using Amos 25.

Before testing the model of the effect of spirituality on the dependent measures, we explored whether the items representing spirituality represented one or more factors. Exploratory factor analysis resulted in three factors: spirituality regarding people (personal), regarding nature (environmental), and regarding “God” (transcendental). However, from a content perspective, the first factor comprised two dimensions: how I view myself spiritually (personal) and how I relate to others spiritually (communal). Moreover, in the group of Torah studiers, these items did not combine into a single factor. We therefore used four dimensions of spirituality, separating “personal” from “communal” spiritually, which is consistent with previous research (Fischer, Citation2010; Kreitler, Citation2016).

Results

compares the demographic characteristics of the two learner groups.

below presents the measures (scales) used and their reliability, which was found acceptable. presents the correlations between the scales.

Table 3. Correlations between scales (two-tailed).

Correlations between measures of a “good life” (Meaning in Life, Quality of Life and Hope) are highly significant, yet correlations between overall spirituality (measured as a single scale) and these scales were low, due to the absence of significant correlations between them and spirituality regarding universe or God “good life" measures.

Differences between the groups

below presents the difference between the two learner groups.

Table 4. T-tests for independent samples (standardized data).

No significant differences were found between group means, with the exception of differences in transcendental spirituality, which was unsurprisingly higher among Torah learners, who also had a higher quality of life. However, testing the correlations between the scales in each group shows group differences do exist, as presented in and .

Table 5a. Correlations between spirituality factors among themselves.

Table 5b. Correlations between spirituality factors and “good life,” by group.

shows that for non-Torah learners, the dimensions of spirituality were more highly correlated among each other, compared to Torah learners, with one exception. Among Torah learners, only transcendental spirituality (faith in God) shows significant correlations with personal spirituality and with communal spirituality.

As seen in , transcendental spirituality (faith in God) and environmental spirituality (nature) show no significant correlations with measures of a “good life.” Among the factors of a “good life,” meaning in life and hope showed similar results; Among Torah learners, personal spirituality showed higher correlations with “good life” measures (excluding quality of life), while communal spirituality showed higher correlations with “good life” measures among non-Torah learners. Apparently, the higher quality of life reported by Torah learners emerged mainly from meaning in life and hope, and to a lesser degree from spirituality.

The final step in this analysis was to explore the role of dimensions of spirituality as antecedences to measures of a “good life,” and specifically to quality of life, the most important factor.

As different correlations emerged in each group, path analyses were conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) based on the maximum likelihood approach (Amos 25) for each group. These analyses also produce the relationships between all variables, revealing the direct and indirect relationships with quality of life.

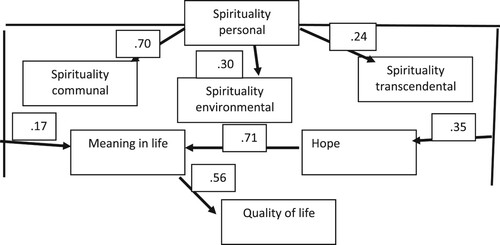

The path analysis results for Torah learners show an acceptable level of fit (goodness of fit measures: χ2 value (14 = 7.105, χ2/Df < .508, p = .488; CFI = .999; NFI = .964; RMSEA = .0000)), supporting the validity of the path model. presents the results of the model.

The model explains 31% of the variance of quality of life. The path model, regression standardized coefficients, and their significance are presented in , including the significant total, direct and indirect relationships for each variable.

Table 6. Total, direct and indirect relationships in the model, Torah learners.

The results show that spirituality has no direct effect on quality of life, and affects quality of life only indirectly through meaning in life. Of all dimensions of spiritually, only personal spiritually had an effect on hope. The most significant variable that affected quality of life was meaning in life, followed by hope.

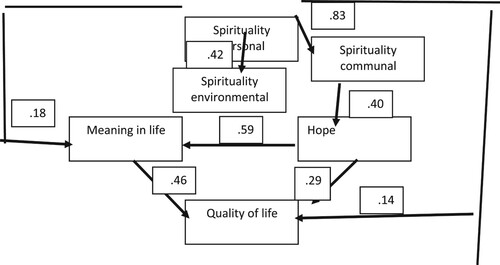

The path analysis results for non-Torah learners show that an acceptable overall fit (goodness of fit measures: (χ2 value (13 = 12.286, χ2/Df < .945, p = .504; CFI = .999; NFI = .963; RMSEA = .0000)), supporting the model, and explaining 57% of the variance of quality of life. The path model, regression standardized coefficients, and their significance are presented in and in , showing the variables’ significant total, direct and indirect relationships.

Table 7. Total, direct and indirect relationships in the model, non-Torah learners.

The relationships to quality of life among non-Torah learners are more developed compared to Tora learners. Quality of life is affected directly by (personal) spirituality and indirectly by (communal) spirituality. In this group, hope had a stronger direct and indirect effect on quality of life than on meaning in life.

Discussion and conclusions

In the current study we explored the following question among adult learners nearing retirement who engage in different types of leisure studies: Do individuals who study Torah/Bible as a leisure activity report higher levels of spirituality compared to learners enrolled in general enrichment studies that are unrelated to spiritual contents? This research question was based on the fact that Torah studies involve connecting with sacred and spiritual contents and exposure to ethical issues, and offer opportunities for philosophical and religious contemplation through which learners might derive meaning.

This question is connected to the following question: What is the unique contribution of each dimension of spirituality to hope and meaning in life, which enhance quality of life.? The research questions were derived from theoretical considerations in the domains of philosophy and psychology with regard to the correlates of meaning of life.

Differences in spirituality

Spirituality comprises four dimensions: personal spirituality, communal spirituality, environmental spirituality, and transcendental spirituality. One surprising finding of the current study is that, in contrast to expected significant differences between Torah learners and general enrichment learners on all dimensions of spiritually, the learner groups showed few differences in self-reported spirituality. Of the four dimensions of spirituality, only transcendental spirituality was found to be significantly higher among Torah learners than among other learners. This difference is expected, as the majority of Torah learners reported being religious and the items measuring transcendental spirituality refer to a sense of closeness to and unity with God. In contrast, the majority of enrichment course learners were secular.

Although it may be tempting to characterize religious Torah learners as having high levels of spirituality, as many believe, the absence of differences between the two groups in the other dimension require an explanation.

One can assume that the type of engagement in leisure time leads to this result. Those who prefer to study in their leisure time instead engaging in more “realistic" activities such as sports or travel, are motivated by a higher desire of spirituality. Another explanation is Torah learners equate nature (universe) with God and therefore are similar in this dimension to the other learner group.

Differences in psychological resources

Torah learners reported higher meaning in life and quality of life, while non-Torah learners reported higher hope.

Meaning in life was expected to reinforce the spirituality of Torah learners. As Greenberg et al. (Citation1986, p. 15) stated, “When a person who has 'what' to live for, he can overcome all the questions of 'how.’” Frankl (Citation1984) wrote that most topics in the Torah provide internal logic, narrative, direction, and coherence in life for learners. This assumption was, however, only partially supported, as the results were not significant. One explanation for this result may be that engagement in learning gives a person a higher meaning in life, regardless of the content of the study. Moreover, the interpretation of meaning in life is subjective (Hill et al., Citation2015).

Similarly, reported levels of hope did not significantly differ across the learner groups. As hope is associated with meaning in life, although affected by personal life circumstances, the explanations for it may be the same.

A significant difference between the two groups was found in quality of life, which was stronger among Torah learners. This result is consistent with previous empirical research that found a link between engagement in spiritual activities and physical and mental health (Matthews et al., Citation2004; Russo-Netzer & Elhai, Citation2015). Moreover, this found difference is supported by evidence that shows that happiness (an element of quality of life) is subjective and dependent on the group to one belongs (Silber & Verme, Citation2012). Torah learners are religious and usually live in closed and homogenous communities. Therefore, they may achieve greater happiness than non-religious learners who live in heterogeneous communities with different socio-economic standards.

Predicting quality of life

The main difference between Torah learners and non-Torah learners was found in the effect of spirituality on quality of life. With respect to Torah learners, transcendental spirituality had no impact on quality of life; only personal spirituality was associated with quality of life. Moreover, this association was indirect, partly through hope and mainly through meaning in life. These results indicate that transcendental spirituality is strongly rooted in personal spirituality and cannot be divided to two types by religious learners. A religious person’s identity is strongly connected to their meaning in life, which then influences quality of life, which was found to be higher among Torah learners than among non-Torah learners.

With respect to non-Torah learners, both personal spirituality and communal spirituality were associated with quality of life. First, personal spirituality was directly associated with quality of life and indirectly associated through meaning in life, but not through hope. Second, communal spirituality had a moderate indirect relation to quality of life through an association with hope. Hope had a direct effect on quality of life and an indirect effect through meaning in life. We may assume that the identity of non-Torah learners, who are mainly not religious, is more complexed than the identity of religious learners: Non-religious individuals are more weakly connected to their community and therefore can separate between their attitude toward themselves and other people, and while striving for social interaction (communal), this can add to their psychologic resources.

In conclusion, the current study investigated the influence of spirituality among older adults who study in their leisure time, as a function of the content of their studies. The findings of this study did not support the main hypothesis, which predicted that the subject of leisure studies (Torah-related studies vs. enrichment studies) affected learners’ spirituality. The current study found that psychologic resources were differentially affected by different types of spirituality. These findings emphasize the importance of further research to generalize differences of sources of spirituality between Torah and other learners, well as its influence on other issues concerning learning among formal students or social behaviors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alkan, O., Kushnir, T., & Davidovitch, N. (2022). Study as an educational leisure activity: The case of Israeli society. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 80(2), 256–272. https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/22.80.256

- Amir, M., Ramati, A., & Arzy-Sharabani, R. (2005). Post-Traumatic symptoms, psychological distress, and quality of life Among survivors of breast cancer in the long term: Initial study. In R. Lev-Wiesel, J. Cwikel, & B. Barak (Eds.), Mental health in Israeli women: Guard yourself (pp. 173–191). Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Charlotte B. and Jack J. Spitzer Department of Social Work, Center for Research and Promotion of Women’s Health, and Myers-JDC-Brookdale, Smokler Center for Health Policy Research. https://brookdale-web.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2018/01/59-05-Guard-REP-HEB.pdf [Hebrew]

- Anandarajah, G., & Hight, E. (2001). Spirituality and medical practice: Using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. American Family Physician, 63(1), 81–89.

- Andrew, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. Americans’ perceptions of life quality. Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-2253-5

- Astedt-Kurki, P. (1995). Religiosity as a dimension of well-being: A challenge for professional nursing. Clinical Nursing Research, 4(4), 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/105477389500400405

- Azulay, N. (2010). The Jewish renewal movement in Israeli secular society (unpublished PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University). [Hebrew].

- Bar-El, E. (2009). Vetalmud torah keneged kulan: Torah Study in Women’s Batei Midrash: A Gendered Perspective.” PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University). [Hebrew].

- Bareli, A., & Bar-On, M. (1999). The challenge of independence.

- Batten, M., & Oltjenbruns, K. A. (1999). Adolescent sibling bereavement as a catalyst for spiritual development: A model for understanding. Death Studies, 23(6), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899200876

- Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. The Guilford Press.

- Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Simon & Schuster.

- Ben-David, R. (2016). This is no Religious-Secular Dialogue: Hybrid Jewish Identities in a Heterogeneous Group: A Case Study from the Israeli Jewish Renewal Field, Ph.D. diss., Bar-Ilan University, 2016. [Hebrew].

- Benjamin, M. H. (2019). Agency as quest and question: Feminism, religious studies, and modern Jewish thought. Jewish Social Studies, 24(2), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.2979/jewisocistud.24.2.02

- Berg-Weger, M., & Morley, J. E. (2020). Loneliness in Old Age: An unaddressed health problem. The Journal Of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 24(3), 243–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1323-6

- Bhabha, H. K. (2002). Theory & criticism? (Political Aspect of Whiteness). 20, 283–288.

- Bowden, J. W. (1998). Recovery from alcoholism: A spiritual journey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 19(4), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/016128498248971

- Braam, A. W., Bramsen, I., van Tilbur, T. G., van der Ploeg, H. M., & Deeg, D. J. (2006). Cosmic transcendence and framework of meaning in life: Patterns among older adults in The Netherlands. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(3), S121–S128. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.3.S121

- Bronk, K. C. (2011). Neuropsychology of adolescent development (12–18-year olds). In A. S. Davis (Ed.), Handbook of pediatric neuropsychology (pp. 47–57). Springer.

- Brown (Hoizman), I. (1996). Torah study for women in the Orthodox view in the 20th century (Unpublished PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University). [Hebrew].

- Cherblanc, J., Bergeron-Leclerc, C., Maltais, D., Cadell, S., Gauthier, G., Labra, O., & Ouellet-Plamondon, C. (2021). Predictive factors of spiritual quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multivariate analysis. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(3), 1475–1493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01233-6

- Chiu, C.-y., Morris, M. W., Hong, Y.-y., & Menon, T. (2000). Motivated cultural cognition: The impact of implicit cultural theories on dispositional attribution varies as a function of need for closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.247

- Chiu, S. I., Lee, J. Z., & Huang, D. H. (2004). Video game addiction in children and teenagers in Taiwan. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 7(5), 571–581.

- Ciarrocchi, J. W., Dy-Liacco, G. S., & Deneke, E. (2008). Gods or rituals? Relational faith, spiritual discontent, and religious practices as predictors of hope and optimism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 120–136. doi:10.1080/17439760701760666

- Cowlishaw, S., Merkouris, S., Chapman, A., & Radermacher, H. (2014). Pathological and problem gambling in substance use treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(2), 98–105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.019

- Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl's concept ofnoogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 200–207. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.10021097-4679(196404)20:2%3C200::AID-JCLP2270200203%3E3.0.CO;2-U https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(196404)20:2<200::AID-JCLP2270200203>3.0.CO;2-U

- Cummins, R. A., & Nistico, H. (2002). Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 37–69. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015678915305

- Davidovitch, N., & Soen, D. (2016). Leisure in the twenty-first century: The case of Israel. Israel Affairs, 22(2), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2016.1140347

- DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197

- Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people Are happy. Psychological Science, 7(3), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00354.x

- Diener, E., Shu, M. E., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://media.rickhanson.net/Papers/SubjectiveWell-BeingDiener.pdf https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Dubrov, A. (2002). Influence of hope, openness to experience and situational control on resistance to organizational change [Master's thesis]. Bar-Ilan University. Hebrew.

- Elor, T. (1998). Next passover: Women and literacy in the religious zionist sector. Am Oved. [Hebrew]

- Epstein, D. (2001). Following the forgotten other – Study of the philosophical teachings of emmanuel levinas. In H. Deutsch, & M. Ben-Sasson (Eds.), The other: Within oneself and between oneself and the other (pp. 180–205). Yediot Aharonoth and Sifrei Hemed Miskal. [Hebrew]

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Growth and crises of the “healthy personality. In M. J. E. Senn (Ed.), Symposium on the healthy personality (pp. 91–146). Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. https://llk.media.mit.edu/courses/readings/Erikson-Identity-Ch2.pdf

- Fallot, R. D. (2007). Spirituality and religion in recovery: Some current issues. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 30(4), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.2975/30.4.2007.261.270

- Feuchtwanger, R. (2011). Becoming a “talmidat-chacham” – Talmudic knowledge, religiosity and gender meet in the world of women scholars (Published PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University). http://www.herzog.ac.il/vtc/old/0099939.pdf. [Hebrew]

- Fischer, E. (2010). The necessity of art. Verso Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1969). The will to meaning: Principles and application of logotherapy. New American Library.

- Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. The psychology of gratitude. In R. A. Emmons, & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), Series in affective science. The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). Oxford University Press.

- Fryback, P. B. (1993). Health for people with a terminal diagnosis. Nursing Science Quarterly, 6(3), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/089431849300600308

- Frytak, J. R. (2000). Assessment of quality of life in older adults. In R. L. Kane, & R. A. Kane (Eds.), Assessing older persons: Measures, meaning, and practical applications (pp. 200–236). Oxford University Press.

- Grant, B. C., & Kluge, M. A. (2012). Leisure and physical well-being. In H. Gibson, & J. F. Singleton (Eds.), Leisure and aging. Theory and practice (pp. 129–142). Human Kinetics.

- Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tom_Pyszczynski2/publication/200008816_Public_Self_and_Private_Self/links/548f78840cf2d1800d86276b/Public-Self-and-Private-Self.pdf

- Groopman, J. (2006). The anatomy of hope. Kinneret Zmora-Bitan. [Hebrew].

- Halivni, D. (1997). Torah study for women. Mayim Midalyo, 8, 15–26. [Hebrew].

- Haught, M. M. (2020). Featured Bookshelf - September 2020 - Tumblr. Libraries' Social Media Images. 179. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/lib-social/179

- Hayosh, T. (2018). Serious leisure: Culture and consumption in modern society. Resling. [Hebrew].

- Heintzman, P., & Patriquin, E. (2012). Leisure and social and spiritual well-being. In H. J. Gibson, & J. F. Singleton (Eds.), In leisure and aging theory and practice (pp. 159–177). Human Kinetics.

- Hill, C. E., Kline, K., Bauman, V., Brent, T., Breslin, C., Calderon, M., Campos, C., Goncalves, S., Goss, D., Hamovitz, T., Kuo, P., Robinson, N., & Knox, S. (2015). What’s it all about? A qualitative study of meaning in life for counseling psychology doctoral students. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 28(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2014.965660

- Hodge, D. R., Bonifas, R. P., & Chou, R. J. (2010). Spirituality and older adults: Ethical guidelines to enhance service provision. Advances in Social Work, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18060/262

- Hopper, E. (2001). On the nature of hope in psychoanalysis and group analysis. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 18(2), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0118.2001.tb00022.x

- Iwasaki, Y. (2006). Counteracting stress through leisure coping: A prospective health study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(2), 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500500155941

- Keng, A. K., & Hooi, W. S. (1995). Assessing quality of life in Singapore: An exploratory study. Social Indicators Research, 35(1), 71–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27522831 https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01079239

- King, K. B., Porter, L. A., Norsen, L. H., & Reis, H. T. (1992). Patient perceptions of quality of life after coronary artery surgery: Was it worth it? Research in Nursing & Health, 15(5), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770150503

- Kitrungrote, L., & Cohen, M. Z. (2006). Quality of life of family caregivers of patients with cancer: A literature review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33(3), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1188/06.ONF.625-632

- Kreitler, S. (2016). Meaning – Its nature and assessment: The general approach and the specific case of body image. In C. Pracana (Ed.), Psychology applications & developments ii advances in psychology and psychological trends series (pp. 78–88). Science Press.

- Levi, O. (2008). The phenomenon of hope as a means of therapy for post-traumatic stress responses.”. Sihot, 22(3), 233–244. [Hebrew].

- Levi, O. (2013). Hope, hardiness, and trauma: Clinical and research development of the concept of hope after the second world War and its use in the psychotherapeutic treatment of chronic and complex PTSD. In G. M. Katsaros (Ed.), Psychology of hope (pp. 1–49). Nova Science.

- Levinas, E. (1981). Otherwise than being or beyond essence (Vol. 4121). Springer.

- Li, C., & F. Lalani. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. This Is How. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning

- Litwin, H. (2006). Social networks and self-rated health: A cross-cultural examination among older Israelis. Journal of Aging and Health, 18(3), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264305280982

- Lykken, D. T. (1999). Happiness: What studies on twins show Us about nature, nurture, and the happiness Set-point. Golden Books.

- Mardhiyah, A., Philip, K., Mediani, H. S., & Yosep, I. (2020). The association between hope and quality of life among adolescents with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Child Health Nursing Research, 26(3), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2020.26.3.323

- Matthews, G., Roberts, R. D., & Zeidner, M. (2004). Seven myths about emotional intelligence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 179–196.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. Jr. (1994). The stability of personality: Observations and evaluations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3(6), 173–175. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182303 https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770693

- Melia, S. P. (2002). Solitude and prayer in the late lives of elder catholic women religious: Activity, withdrawal, or transcendence? Journal of Religious Gerontology, 13(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1300/J078v13n01_05

- Menninger, K. (1959). THE ACADEMIC LECTURE. American Journal of Psychiatry, 116(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.116.6.481

- Mickley, J. R., Soeken, K., & Belcher, A. (1992). Spiritual well-being, religiousness and hope among women with breast cancer. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 24(4), 267–272.

- Miller, W. R., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist, 58(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.24

- Murray, R. B., & Zentner, J. P. (1989). Nursing concepts for health promotion. Prentice Hall.

- Nehushtan, G. (1980). Leisure as a factor in the development of the elderly. Gerontology, 15-16, 49–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23479067 [Hebrew]

- Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

- O'Boyle, C. A., McGee, H. M., & Joyce, C. R. B. (1994). Quality of life: Assessing the individual. Advances in Medical Sociology, 5, 159–180.

- Park, J., Roh, S., & Yeo, Y. (2012). Religiosity, social support, and life satisfaction among elderly Korean immigrants. The Gerontologist, 52(5), 641–649. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr103

- Passmore, A., & French, D. (2003). The nature of leisure in adolescence: A focus group study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(9), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260306600907

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

- Reed, P. (1991). Spirituality and mental health in older adults: Extant knowledge for nursing. Family & Community Health, 14(2), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003727-199107000-00004

- Roman, N. V., Mthembu, T. G., & Hoosen, M. (2020). Spiritual care – ‘A deeper immunity’ – A response to COVID-19 pandemic. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 12(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2456

- Ross, T. (2007). Expanding the palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and feminism. Am Oved. [Hebrew].

- Routledge, C., & Juhl, J. (2010). When death thoughts lead to death fears: Mortality salience increases death anxiety for individuals who lack meaning in life. Cognition & Emotion, 24(5), 848–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930902847144

- Russo-Netzer, P. (2020). Meaning in the psychotherapy map: Theory, research, and application. Psychoactualiya, (July), 14–19. [Hebrew].

- Russo-Netzer, P., & Elhai, N. (2015). Spiritual chaplaincy for at-risk populations. Evaluation report for JDC Israel (Joint ASHALIM). [Hebrew].

- Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1999). Reports of subjective well-being: Judgmental processes and their methodological implications. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), In well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 61–84). Russell Sage Foundation Clinical Applications. https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/780/docs/99_wb_schw_strack_reports_of_wb.pdf

- Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In M. Csikszentmihalyi (Ed.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279–298). Springer. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6d8b/a92034df85cc932f8faea39507bd58f481c8.pdf?_ga=2.135142129.1716280327.1608123498-511505341.1605186054

- Sheleg, Y. (2010). The Jewish renaissance in Israeli society: The emergence of a new Jew. Israel Democracy Institute. [Hebrew].

- Shenhav, Y. (2001). Introduction: Identity in a postnational society. Teorya Uvikoret, 19, 5–16. [Hebrew].

- Shmotkin, D., & Shrira, A. (2012). On the distinction between subjective well-being and meaning in life: Regulatory versus reconstructive functions in the face of a hostile world. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 143–163). Routledge.

- Silber, J., & Verme, P. (2012). Relative deprivation, reference groups and the assessment of standard of living. Economic Systems, 36(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2011.04.006

- Skevington, S. M., & Böhnke, J. R. (2018). How is subjective well-being related to quality of life? Do we need two concepts and both measures? Social Science & Medicine, 206, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.005

- Snyder, C. R. (2000). The past and possible futures of hope. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.11

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

- Soen, D., & Rabinovich, D. (2011). Utz ly, gutz ly: al biluy sheot hapnay shel bnay noar chilonim vedatim bisrael [On the leisure habits of secular and religious teens in Israel]. Hachinuch Usvivo, 33, 229–248

- Tornstam, L. (2005). Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. Springer.

- Twenge von Humboldt, S., Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N. M., Arias-Merino, E. D., Costa, A., Cabras, E., Low, G., & & Leal, I. (2020). Smart technology and the meaning in life of older adults during the COVID-19 public health emergency period: A cross-cultural qualitative study. International Review of Psychiatry, 32(7–8), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1810643

- Weber, M. (2010). The protestant ethic and the spirit of eapitalism. Oxford University Press.

- The WHOQOL Group. (1998). Development of the world health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine, 28(3), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798006667

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2012). User manual. Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse. https://www.who.int/toolkits/whoqol