ABSTRACT

Background

Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma (PGIL), an uncommon subtype of lymphoma, accounts for 1%–4% of gastrointestinal cancers. This study, therefore, aimed to investigate the current 10-year epidemiology and outcomes of PGIL.

Methods

This retrospective study involved a hospital-based chart review to analyze the epidemiology, clinical features, predisposing factors, and clinical outcomes of patients diagnosed with, and treated for, PGIL. Data covering 10 years was collected of Thai patients aged ≥ 15 years who had been diagnosed as PGIL with pathological confirmation and treated at Siriraj Hospital, Thailand.

Results

A total of 175 PGIL patients were enrolled. Their median age was 60 years (range, 20–98), with a male predominance. The stomach was the most common site of gastrointestinal (GI) organ involvement by lymphoma (38.9%), followed by the small intestine (23.4%) and multiple sites of GI involvement (23.4%). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) had the highest proportion of PGIL, accounting for 61.1%. The median patient follow-up time was 13.9 months (range: 0–104.9 months). The median overall survival (OS) of PGIL patients was not reached during the 10 years, with a 5-year OS of 64.4%. The probability of having a better OS was demonstrated in patients with a good performance status who received a rituximab-containing regimen.

Conclusions

The stomach was the most common site of lymphoma involvement in the GI tract, with DLBCL accounting for the highest proportion of those patients. The long-term survival outcome was significantly improved in patients with good performance status and rituximab exposure.

Trial registrationNot applicable.

Background

Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma (PGIL) is an uncommon subtype of cancer, accounting for 1%–4% of gastrointestinal cancers [Citation1]. Several predisposing factors, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, Hepatitis C virus, immunosuppressive or chemotherapy exposure, and inflammatory bowel disease, are possible causes of PGIL [Citation2–5]. From previous studies, the stomach is the most common site of PGIL, followed by the small intestine [Citation6,Citation7]. A study by Zeggai S et al. found that the most common histological lymphoma subtype was mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma [Citation6], whereas diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was the most common lymphoma subtype identified by another study [Citation7]. Although a previous study of 120 PGIL Thai patients was published in 2004, its findings are now out of date [Citation8]. For one thing, the latest lymphoma classifications are now based on the revised 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid neoplasms, and several aspects of current chemotherapy treatments have changed since the prior classifications were promulgated in 2008 [Citation9,Citation10]. Furthermore, immunochemotherapy was commonly provided for the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients throughout the last decade. Therefore, this study set forth to investigate the current status of the 10-year epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of PGIL in Thailand.

Methods

The study was conducted on Thai PGIL patients presenting from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2015, at Siriraj Hospital, Thailand’s largest national tertiary referral center. The inclusion criteria were (1) a patient age ≥ 15 years; (2) the patient was of Thai ethnicity; (3) the presence of lymphoma involving the gastrointestinal tract as an initial manifestation; and (4) the disease was diagnosed and pathologically confirmed at Siriraj Hospital. The exclusion criteria were primary nodal lymphomas with secondary gastrointestinal tract involvement and lymphomas with a dominant nodal involvement. The included cases were independently carried out by the two investigators (W.O. and T.R.). If there were discordant of eligible patients, both investigators would discuss the disagreement and made the final decision. All available tissues were re-evaluated to confirm lymphoma diagnosis and lymphoma’s subtypes by a pathologist (T.P.). The protocol for this study involved a hospital-based chart review to analyze the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, predisposing factors, the performance statuses (PS) of the patients re-evaluated from the document at the initial diagnosis period, and clinical outcomes of the patients diagnosed with and treated for PGIL. The deadline for follow-up was January 1, 2016. The protocol was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Terminology

In our study, PGIL presentation was defined when a patient had a new diagnosis of any lymphoma subtype which primarily involved the GI organs, including the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Excluded were a GI lymphoma with dominant nodal involvement as well as nodal lymphomas with secondary GI tract involvement [Citation7]. Overall survival (OS) was set as the interval between the time of diagnosis and either death or the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Clinical characteristics are presented as medians and interquartile ranges, continuous variables as means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The prevalence of the lymphoma subtypes of PGIL is shown as percentages. Continuous data were compared between groups using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data of the groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Binary logistic regression analyses were used to determine the relationships between the variables, with an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) being calculated for each significant variable. The factors associated with OS in the PGIL patients were compared using a log-rank test and presented as a Kaplan–Meier survival curve. Univariate and multivariate predictors of the survival outcomes were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards analysis (backward stepwise method) and presented as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. A p-value less than .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics, manifestations, and initial laboratory findings

The 175 PGIL patients enrolled had a median age was 60 years (range, 20–98) and a male predominance (60%). The PS of the patients, which were based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) classification system, were ECOG-PS 0, 0.6%; 1, 47.4%; 2, 41.1%; 3, 9.7%; and 4, 0.6%. Most of the patients (82.8%) had abdominal pain as a presenting symptom. Other common initial manifestations were palpable abdominal mass (29.3%), upper GI bleeding (20.1%), lower GI bleeding (12.1%), gut obstruction (10.9%), hollow viscus organ perforation (10.4%), chronic diarrhea (10.4%), superficial lymphadenopathy (8%), and dysphagia (7%). Over half of the patients presented with B symptoms, of which 50.6% were significant weight loss, 12.6% were fever, and 2.9% were night sweats (). Because there were various lymphoma subtypes, we re-evaluated the staging of all cases based on the Ann Arbor staging system. The staging 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 were 30.9%, 20.0%, 10.3% and 29.7%, respectively.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics and initial investigations.

As to the initial laboratory findings, the complete blood count and liver function test results are summarized in . The median lactate dehydrogenase level was 380 U/l (range: 201–7,208 U/l). Nearly 15% (23 out of 159 cases) of the patients had minimal or focal bone marrow involvement evaluated by pathologists. Viral serology and antigen found that only 3% of cases were positive for anti-HIV. Hepatitis B virus antigens were found in 15.5% of cases, while less than 5% of patients had hepatitis C infection. Furthermore, nearly half (45.2%) of the gastric lymphoma patients were positive for H. pylori. Two out of twelve BL patients were positive for anti-HIV, whereas positive blood results were shown by less than 5% (3/82) of DLBCL patients. No patient had celiac disease or autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

GI organ involvement and lymphoma subtypes

The stomach was the most common site of GI-organ involvement by lymphoma (38.9%), followed by the small intestine (23.4%), multiple-organ involvement (23.4%), and the large intestine (14.3%). As to the 88 patients with gastric involvement, lesions were located at multiple sites in 42 (47.7%) cases, the fundus in 8 (9.1%) cases, the body in 16 (18.2%) cases, the cardia in 10 (11.4%) cases, and the antrum in 12 (13.6%) cases. Additionally, the ileum and duodenum were the most and second-most common sites of small intestine involvement by lymphoma, with incidences of 34.5% and 25.3%, respectively, whereas lymphoma involvement in the large intestine was typically found in the caecum (27.5%) and ascending colon (15.7%). Of the 41 patients with multiple GI organ involvement, 2 (4.9%) cases involved the esophagus and stomach; 11 (26.8%) the stomach and small intestine; 21 (51.2%) the small and large intestines; 3 (7.3%) the stomach, and the small and large intestines; 2 (4.9%) the stomach and pancreas; and 2 (4.9%) the stomach and large intestine ().

Table 2. Sites of gastrointestinal involvement, lymphoma subtypes, and treatments.

Moving on to the pathological findings, DLBCL ranked as the most frequent lymphoma subtype, accounting for 61.1% of PGIL cases. In decreasing order of frequency, the other subtypes were MALT, 13.1%; small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (SLL/CLL), 5.1%; mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), 4.6%; Burkitt lymphoma (BL), 4%; peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), not otherwise specified (NOS), 3.4%; follicular lymphoma (FL), 2.9%; enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), 1.1%; NK/T-cell lymphoma (NKTCL), 2.9%; Hodgkin lymphoma, 0.6%; and B-cell lymphoma, unclassified, 0.6% (). The stomach was the most common location of several lymphoma subtypes (DLBCL, BL, and MALT), followed by the small intestine and then the large intestine. In contrast to B-cell lymphomas, T-cell lymphoma subtypes mostly involved the small intestine.

Treatments and clinical outcomes

Six percent of patients who did not indicate treatment were closely followed, with no immediate need for treatment. The proportion of patients requiring an excisional mass was over 50%. Besides, up to three-quarters (74.2%) of patients received chemotherapy. Rituximab (monoclonal anti-CD20) was integrated with conventional chemotherapy regimens in 47.1% of the chemotherapy-treated cases. Radiotherapy was one of the therapeutic options for patient treatment, accounting for 7.2% of cases ().

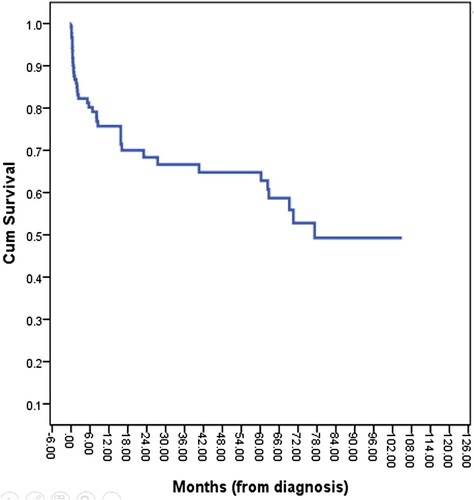

The median follow-up time for the surviving patients was 13.9 months (range: 0–104.9 months). The median OS of PGIL patients was not reached during the 10-year study period, with the 3- and 5-year OSs being 66.2% and 64.4%, respectively (). In this subgroup of PGIL patients, the factors affecting OS were age (≤ 60 years vs. > 60 years); ECOG PS (0–1 vs. 2–4); GI organ involvement (stomach vs. intestine); Ann Arbor staging group (limited vs. advanced); NHL group (indolent vs. aggressive); and rituximab exposure (no rituximab treatment vs rituximab-integrated treatment). The aggressive NHL group included DLBCL, BL, MCL, PTCL-NOS, EATL, ALCL, and NKTCL, whereas MALT, FL, and SLL/CLL were a subset of the indolent NHL group.

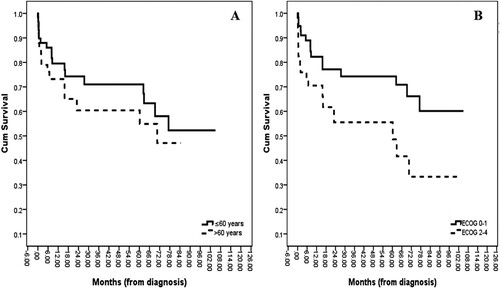

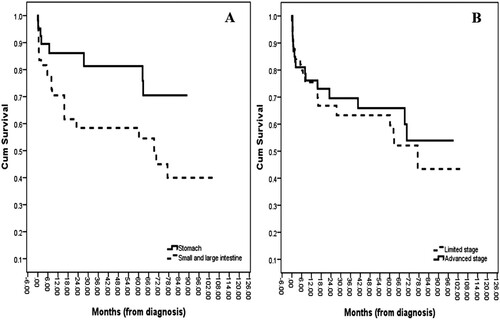

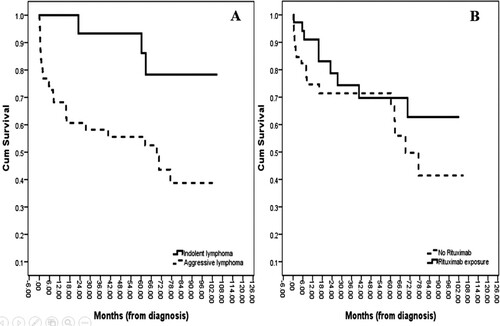

Firstly, the median OS for patients aged less than 60 years was not reached, whereas a median OS of 70.5 months was revealed for patients aged over 60 (p = .356; A). Moreover, when we divided the patients into ECOG-PS 0–1 vs. ECOG-PS 2–4, the median OSs were not reached and 60.3 months, respectively (p = .018; B). Furthermore, the gastric lymphoma patients had a median OS of not reached whereas the intestinal lymphoma patients had a median OS of 69.2 months (p = .042; A). Also, there was no statistical difference in the OSs of the limited-stage and advanced-stage groups (median OSs of 77.3 months vs. not reached, respectively, with p = .530; B). As well, the median OS for the indolent NHL patients was not reached as opposed to 70.5 months for those with an aggressive NHL (p = .011; A). Lastly, although the median OS for the rituximab-exposure group was numerically higher than the no-rituximab treatment group, the difference did not reach statistical significance (not reached vs. 69.2 months, respectively, with p = .136; B). The multivariate analysis was adjusted for all risk factors that were potentially associated with the survival time of the PGIL patients, which was defined as p < .2. An increased probability of a better OS was demonstrated by patients with a good ECOG-PS and who received a rituximab-integrated regimen ().

Figure 2. Overall survival curves according to (A) age groups (P-value = 0.352); (B) ECOG-PS (P-value = 0.015).

Figure 3. Overall survival curves according to (A) sites of lymphoma involvement (P-value = 0.036); (B) Staging groups (P-value = 0.528).

Figure 4. Overall survival curves according to (A) lymphoma groups (P-value = 0.005); (B) Rituximab exposure groups (P-value = 0.128).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analyses for overall survival in PGIL patients (months).

Clinical outcome of B-cell lymphoma subtypes

Because rituximab is a potential target medication for only B-cell lymphoma expressing CD-20, subgroup survival analysis of only B-cell lymphoma subtypes was performed. The multivariate analysis demonstrated that good ECOG-PS and those who received a rituximab-integrated regimen had better prognostic factors on OS in these patients, which is compatible with the full analysis (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

This 10-year cohort study in Thailand focused on PGIL and included 175 patients. Their mean age was 61 years with a male predominance, which is similar to the profile of previous studies [Citation7,Citation11,Citation12]. Almost all of the patients presented with abdominal pain. Notably, GI bleeding was a typical presentation in our cohort, accounting for approximately one-third of the patients, which is higher than the corresponding figure in prior reports [Citation13,Citation14]. Similar to previous studies, the stomach and small intestine displayed the most and second-most common organ involvement of lymphoma [Citation7,Citation12]. From the pathological findings, DLBCL remained the most common lymphoma subtype in the PGIL patients, consistent with a recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database report [Citation15]. However, the second- and third-most common in our study were MALT and SLL/CLL, respectively, which contrasted with FL and MCL in the previous study [Citation15]. We hypothesize that the difference is due to the ethnic impact on the variations in the proportions of each lymphoma subtype involving the GI system. Interestingly, at the initial diagnosis, approximately 25% of the patients had a multiple GI organ involvement that involved adjacent organs. Hence, we believe that with a newly diagnosed PGIL patient, an extensive endoscopic workup could be of benefit for the patient’s complete staging. H. pylori were found in nearly half of the primary gastric lymphoma patients in our study, which was the same number found by a prior study [Citation16].

The five-year OS identified by our study (64.4%) was markedly higher than the figure previously found for the Asian/Pacific Islander population (39.5%) [Citation15]. Thanks to the novel treatments introduced in recent years, almost 50% of the chemotherapy-treated patients received rituximab combined with conventional chemotherapy. This might be why the long-term survival outcome of the PGIL patients in our study was higher than the previous results. Moreover, our multivariate analysis confirmed that rituximab was a favorable factor for the survival outcome of lymphoma patients. Apart from this factor, a good ECOG-PS was also critical in providing a long-term survival benefit in our study, consistent with the results of a previous study of DLBCL lymphoma patients [Citation17].

This study had some limitations. Firstly, because it was a retrospective study, missing data was unavoidable. Furthermore, a variety of treatment protocols were decided by the primary treating physicians. It is therefore expected there would be some heterogeneity for each patient which might have affected the individual clinical responses and survival outcomes.

Conclusions

The stomach was the most common location for lymphoma involvement in the GI tract, while DLBCL accounted for the large majority of those patients. The long-term survival outcomes were significantly improved by good performance status and the exposure of patients to rituximab.

List of abbreviations

BL: Burkitt lymphoma; CI: confidence interval; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; EATL: enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; ECOG: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FL: follicular lymphoma; GI: gastrointestinal; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; HR: hazard ratio; MALT: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MCL: mantle cell lymphoma; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NKTCL: NK/T-cell lymphoma; OS: overall survival; PGIL: primary gastrointestinal lymphoma; PS: performance statuses; PTCL-NOS: peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SLL/CLL: small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia; WHO: World Health Organization.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were conducted under the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and following the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and all of its subsequent revisions. The local ethics body approved the study, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. Given the study’s retrospective nature, the need for written informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

A copy of the consent document is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of Hematology.

Authors’ contributions

All authors designed the study. M.M., W.O. and T.R. collected the data. All available tissues were re-evaluated to confirm lymphoma diagnosis and lymphoma’s subtypes by T.P..W.O. performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. M.M., T.R., and T.P. supervised the project and made critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms. Pattaraporn Tunsing for assistance with the data collection, statistical analyses, and manuscript submission process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Peng JC, Zhong L, Ran ZH. Primary lymphomas in the gastrointestinal tract. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(4):169–176.

- Muller AM, Ihorst G, Mertelsmann R, et al. Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL): trends, geographic distribution, and etiology. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(1):1–12.

- Lewin KJ, Ranchod M, Dorfman RF. Lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 117 cases presenting with gastrointestinal disease. Cancer. 1978;42(2):693–707.

- Couronne L, Bachy E, Roulland S, et al. From hepatitis C virus infection to B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(1):92–100.

- Rostami Nejad M, Aldulaimi D, Ishaq S, et al. Geographic trends and risk of gastrointestinal cancer among patients with celiac disease in Europe and Asian-Pacific region. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6(4):170–177.

- Zeggai S, Harir N, Tou A, et al. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in Western Algeria: pattern of distribution and histological subtypes (retrospective study). J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7(6):1011–1016.

- Shirsat HS, Vaiphei K. Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas—A study of 81 cases from a Tertiary Healthcare Centre. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(3):290–292.

- Sukpanichnant S, Udomsakdi-Auewarakul C, Ruchutrakool T, et al. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in Thailand: a clinicopathologic analysis of 120 cases at Siriraj Hospital according to WHO classification. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35(4):966–976.

- Jiang M, Bennani NN, Feldman AL. Lymphoma classification update: T-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphomas, and histiocytic/dendritic cell neoplasms. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(3):239–249.

- Leonard JP, Martin P, Roboz GJ. Practical implications of the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid and myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2708–2715.

- Papaxoinis G, Papageorgiou S, Rontogianni D, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 128 cases in Greece. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study (HeCOG). Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(10):2140–2146.

- Radic-Kristo D, Planinc-Peraica A, Ostojic S, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma in adults: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics. Coll Antropol. 2010;34(2):413–417.

- Kolve M, Fischbach W, Greiner A, et al. Differences in endoscopic and clinicopathological features of primary and secondary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. German Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Study Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(3 Pt 1):307–315.

- Lightner AL, Shannon E, Gibbons MM, et al. Primary gastrointestinal Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the small and large intestines: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(4):827–839.

- Shannon EM, MacQueen IT, Miller JM, et al. Management of primary gastrointestinal Non-Hodgkin lymphomas: A population-based survival analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(6):1141–1149.

- Malipatel R, Patil M, Rout P, et al. Primary gastric lymphoma: clinicopathological profile. Euroasian J Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2018;8(1):6–10.

- Han Y, Qin Y, He XH, et al. Retrospective analysis of the clinical features and prognostic factors of 370 patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2018;40(6):456–461.