ABSTRACT

Objectives The aim of this retrospective analysis was to assess the incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) during and after ruxolitinib treatment. Methods Between February 2013 and February 2020, 224 patients with MPN were treated using ruxolitinib at Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Of these, 6 had chronic, and 56 had resolved HBV infection, including 43 patients who received combination treatment with thalidomide, prednisone, and stanozolol (TSP) during ruxolitinib treatment. Results Two patients with chronic HBV infection who did not take any antiviral prophylaxis developed HBV reactivation and hepatitis flare. The other four patients with chronic HBV infection, who took antiviral prophylaxis before ruxolitinib treatment, did not develop HBV reactivation. Also, no patients with resolved HBV infection received antiviral prophylaxis and developed HBV reactivation. Conclusion This study demonstrated that HBV reactivation and hepatitis flare might commonly occur a few months after initiating ruxolitinib treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection who did not take antiviral prophylaxis, especially in combination with TSP. Still, it was extremely rare in patients with resolved HBV infection.

Introduction

Certain therapies for hematologic malignancies, including anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and ibrutinib, have been associated with an increased risk of HBV reactivation in patients previously infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) [Citation1–4]. In general, the risk of HBV reactivation is different in patients with chronic HBV (hepatitis B surface antigen, i.e. HBsAg positive) and resolved HBV (HBsAg negative and antibody to hepatitis B core antigen, i.e. HBcAb positive) [Citation4]. Ruxolitinib, a potent Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, was the first targeted drug approved for treating myelofibrosis (MF) based on the results of two pivotal phase III controlled myelofibrosis study with oral JAK inhibitor treatment (COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II)[Citation5,Citation6] and hydroxyurea-resistant and refractory polycythemia vera (PV) based on the results of the randomized study on efficacy and safety in polycythemia Vera with JAK inhibitor INCB018424 versus best supportive care (RESPONSE study)[Citation7,Citation8]. Ruxolitinib impairs dendritic cell and T-cell functions, leading to reduced cytokine production that results in impaired control of silent infections and an increased risk of reactivation of viruses, such as herpes zoster and hepatitis B [Citation9–14]. A few patients were reported to experience hepatitis B reactivation after ruxolitinib treatment [Citation11,Citation15,Citation16]. Nevertheless, the actual incidence of HBV reactivation in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) and chronic or resolved HBV infection during and after ruxolitinib treatment remains unclear. Therefore, this retrospective analysis was performed to assess the incidence of HBV reactivation among such patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

All patients with MPN during or after ruxolitinib treatment at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) between February 2013 and February 2020 were screened for HBV. Patients with chronic and resolved hepatitis B were enrolled in the current study. Clinical characteristics were recorded, including previous or combination treatment with TSP and other chemotherapies. Liver function tests were routinely monitored in all patients with MPN.

Definitions

HBV reactivation was defined as the elevation of HBV viral load to 500 IU/mL. HBsAg reverse seroconversion was defined as the reappearance of HBsAg. Hepatitis flare was defined as the serum alanine transaminase (ALT) level more than 100 IU/L, or a threefold rise in the ALT level that exceeded the reference range. Chronic HBV was defined as HBsAg positive (normal range: <0.05), and resolved HBV was defined as HBsAg negative and HBcAb positive (normal range: <1.00). To diagnose hepatitis attributed to HBV reactivation, clinicians must exclude the evidence of hepatic infiltration by underlying malignancy, hepatotoxic drugs, recent transfusion, and other systemic infections for all patients [Citation17,Citation18].

Laboratory tests

Liver functions, HBV serologic test, and HBV DNA were performed on a monthly basis after ruxolitinib treatment using chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay; if normal results were observed for 3 months, the interval of testing was extended to 3 months. HBV DNA was detected and quantified by a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Outcomes and follow-up

The primary endpoint was the incidence of HBV reactivation during and after ruxolitinib treatment. Serum samples were collected at baseline and during every treatment (1 month or more) to check liver function, HBV viral loads, and HBsAg levels in HBsAg-positive patients and in patients with chronic and resolved HBV infection.

Results

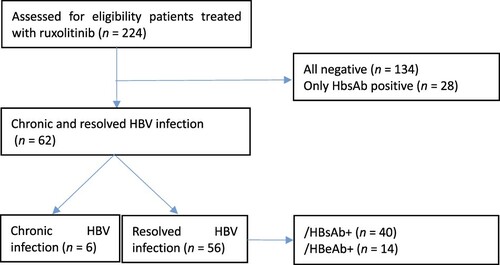

Between February 2013 and February 2020, 224 patients with MPN were treated with ruxolitinib at PUMCH; 6 patients had chronic HBV infection, and 56 had resolved HBV infection. Patients negative for all serological tests of HBV and positive for HBsAb only were excluded (). shows the baseline characteristics of 62 patients enrolled in the study. The median duration of follow-up from initiating ruxolitinib treatment was 23.21 months (2.22–52.93 months). Forty-three patients received combination treatment with thalidomide, prednisone, and stanozolol at the same time. Two patients with chronic HBV infection who did not take any antiviral prophylaxis developed HBV reactivation and hepatitis flare. The other four patients with chronic HBV infection took antiviral prophylaxis before ruxolitinib treatment. Two of them were treated with a TSP regimen at the same time; no one developed HBV reactivation. Also, no patients with resolved HBV infection received antiviral prophylaxis and developed HBV reactivation and HBsAg reverse seroconversion.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with chronic or resolved HBV infection who were treated with ruxolitinib (n = 62)

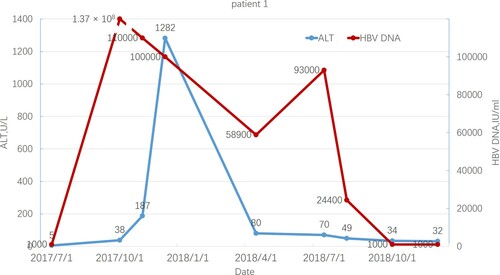

Patient 1 was a 54-year-old woman diagnosed with MF 18 years before reactivation. At baseline, she was HBsAg/HBeAg/HBcAb positive and HBV DNA undetectable. She was treated with ruxolitinib, thalidomide, prednisone, and stanozolol but without routine antiviral prophylaxis. Two months after starting ruxolitinib, she developed detectable HBV DNA at 1.37 × 108 IU/mL. The alanine aminotransferase level reached the maximum levels at 1282 U/mL approximately 4 months later, while the bilirubin levels were always normal. The patient was treated with entecavir (ETV) without the discontinuation of ruxolitinib and other medications for MF. ALT level rapidly decreased, but HBV-DNA levels remained undetectable approximately 1 year later. shows the trends of the ALT level and HBV-DNA copies. The patient died of blast transformation 20 months after initiating ruxolitinib treatment.

Figure 2. ALT level and HBV-DNA copies in patient 1 during ruxolitinib treatment. The start date of ruxolitinib and TSP was July 1, 2017.

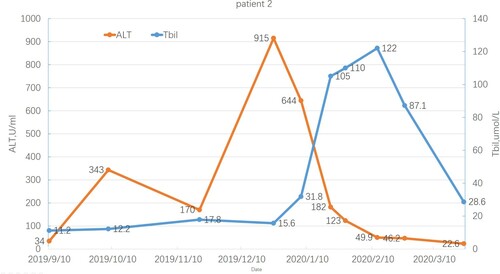

Patient 2 was a 43-year-old man diagnosed with MF 9 years before reactivation. At baseline, he was HBsAg/HBeAg/HBcAb positive and HBV DNA undetectable. He was treated with ruxolitinib, thalidomide, prednisone, and stanozolol but without routine antiviral prophylaxis. Two months after initiating ruxolitinib, he developed detectable HBV DNA at 1610 IU/mL, while ALT and bilirubin levels gradually increased to a maximum of 915 U/L and 122 µmol/L, respectively. He was treated with ETV; stanozolol was discontinued, but not ruxolitinib. HBV-DNA levels were undetectable, and ALT/bilirubin gradually decreased to normal 2 months after starting ruxolitinib treatment. shows the trends of ALT and total bilirubin levels.

Discussion

The reactivation of HBV following chemotherapy and targeted therapy is an emerging issue in the field of hematology. Risk groups are determined by the HBV serological status, type of immunosuppression, and type of treatment to be used as prophylaxis. One meta-analysis revealed that among patients receiving chemotherapy for solid tumors, the reactivation risk ranged between 4% and 68% in patients with chronic HBV infection and 0.3%–9% in patients with resolved HBV infection [Citation19]. However, for therapies based on B-cell-depleting agents, such as rituximab, the reactivation risk was 4.3%–23.8%, even in patients with resolved HBV infection [Citation2–4,Citation20]. Ruxolitinib is a novel inhibitor of JAK that was recently approved for the treatment of patients with MPN. Consistent with the mechanism of action, ruxolitinib impairs dendritic cell and T-cell functions, leading to impaired cytokine production that results in the reduced control of silent infections and, as a consequence, infections (including opportunistic infections) and viral (re-)activation. HBV or VZV (varicella-zoster virus) reactivation is an adverse event that has been frequently reported in all previous trials [Citation5,Citation6,Citation14,Citation15]. Most clinical trials did not report HBV reactivation, but the enrollment criteria excluded patients with chronic HBV infection, while the number of patients with resolved HBV infection was not mentioned [Citation21]. HBV reactivation during or after ruxolitinib treatment has been described in only two patients with resolved infection [Citation11] and two with chronic HBV infection [Citation15,Citation16]. No studies have delineated the incidence of HBV reactivation in such patients. Therefore, the risk of reactivation related to ruxolitinib treatment in different HBV serological statuses is an intriguing issue worth investigating.

In this retrospective study on ruxolitinib-treated patients with evidence of HBV infection, HBV reactivation was observed in two patients with chronic infection but not in patients with resolved HBV infection. The data showed that HBV reactivation was a real threat to patients with chronic HBV infection and MPN who were treated using ruxolitinib. Rituximab and ibrutinib are known to increase the risk of HBV reactivation in patients for a year or more after discontinuing treatment [Citation20,Citation22]. However, the two patients in this study developed reactivation approximately 2 months after they started ruxolitinib treatment, which is consistent with previous findings [Citation11,Citation15]. The difference in reactivation time might indicate different degrees of immunosuppression. The ruxolitinib treatment was not discontinued during the reactivation of HBV infection and severe hepatitis flare. Moreover, liver function tests gradually improved, which indicated that ruxolitinib had no direct hepatotoxic effect.

Still, the combination treatment with TSP might increase the risk of HBV reactivation and worsen the liver function test even further. In the present study, 69.4% of patients with MF were treated with combination treatment with TSP to improve anemia or thrombocytopenia during ruxolitinib treatment [Citation23]. Preclinical studies reported that steroids directly stimulated HBV replication and gene expression [Citation24,Citation25], while stanozolol was a major medication that induced abnormal liver function tests even at low doses [Citation26]. Therefore, compared with previous studies that showed no significant hepatitis flare soon after HBV reactivation [Citation11,Citation15], the liver function tests in this study rapidly deteriorated after HBV reactivation in two patients, probably because of the combination of TSP with ruxolitinib. Therefore, an antiviral prophylaxis strategy is strongly recommended for patients who take ruxolitinib combined with TSP. Finally, all other patients with chronic HBV infection who received antiviral prophylaxis before ruxolitinib treatment did not develop HBV reactivation and significantly abnormal liver function tests.

Our results demonstrated that no patient with resolved HBV infection had HBV reactivation, even if most of the patients received ruxolitinib combined with TSP. Therefore, patients with resolved HBV infection might have a low risk of HBV reactivation according to the criteria of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines. For patients at low risk of HBV reactivation, the AGA guidelines do not recommend antiviral prophylaxis's routine use [Citation4]. Some data indicated that HBsAb protected against reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection [Citation1]. However, the protective effect of HBsAb was not confirmed as no patients with resolved HBV infection developed reactivation.

This study had three major limitations. First, retrospective observations were limited by interpatient variability in HBV monitoring. Second, the study had a small sample size; nonetheless, it is still the largest study assessing HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or resolved HBV infection during or after ruxolitinib treatment. Third, the median follow-up was relatively short (23.21 months). Therefore, it is possible that the reactivation rate in the cohort was higher with a longer follow-up. Moreover, many questions about the impact of ruxolitinib on HBV reactivation in this population remained unanswered. For example, most patients with myelofibrosis had to take ruxolitinib lifelong, hence the duration of the increased risk and HBV reactivation prophylaxis after using ruxolitinib were difficult to determine, especially after discontinuing treatment. Unlike rituximab, which is known to increase the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with previous HBV infection for a year or more after discontinuing the treatment, ruxolitinib led to HBV reactivation during treatment rather than after discontinuation. This phenomenon was also observed in other studies [Citation11,Citation15,Citation16].

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that HBV reactivation and hepatitis flare might commonly occur a few months after initiating ruxolitinib treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection, especially when combined with TSP, while it is extremely rare in patients with resolved HBV infection. Antiviral prophylaxis was recommended for patients with chronic HBV infection who were treated with ruxolitinib. Further studies are needed to establish whether patients with resolved HBV infection could benefit from the same antiviral prophylaxis.

Statement of ethics

The trial was approved by the Ethical Institutional Review Board of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Also, all the patients gave written informed consent.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus exposure undergoing rituximab-containing chemotherapy for lymphoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol: Offic J Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2014 Nov 20;32(33):3736–3743.

- Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol: Offic J Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2009 Feb 1;27(4):605–611.

- Matsue K, Kimura S, Takanashi Y, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after rituximab-containing treatment in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2010 Oct 15;116(20):4769–4776.

- Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, et al. American Gastroenterological Association i. American Gastroenterological Association institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jan;148(1):215–219.; quiz e16-7.

- Harrison CN, Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian JJ, et al. Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study of ruxolitinib vs best available therapy for myelofibrosis.. Leukemia. 2016 Aug;30(8):1701–1707.

- Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Gupta V, et al. Effect of ruxolitinib therapy on myelofibrosis-related symptoms and other patient-reported outcomes in COMFORT-I: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol: OfficJ Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2013 Apr 1;31(10):1285–1292.

- Verstovsek S, Vannucchi AM, Griesshammer M, et al. Ruxolitinib versus best available therapy in patients with polycythemia vera: 80-week follow-up from the RESPONSE trial. Haematologica. 2016 Jul;101(7):821–829.

- Vannucchi AM, Verstovsek S, Guglielmelli P, et al. Ruxolitinib reduces JAK2 p.V617F allele burden in patients with polycythemia vera enrolled in the RESPONSE study. Ann Hematol. 2017 Jul;96(7):1113–1120.

- Gill H, Leung GMK, Seto WK, et al. Risk of viral reactivation in patients with occult hepatitis B virus infection during ruxolitinib treatment. Ann Hematol. 2019 Jan;98(1):215–218.

- Eyal O, Flaschner M, Ben Yehuda A, et al. Varicella-zoster virus meningoencephalitis in a patient treated with ruxolitinib. Am J Hematol. 2017 May;92(5):E74–EE5.

- Perricone G, Vinci M, Pungolino E. Occult hepatitis B infection reactivation after ruxolitinib therapy . Dig Liver Dis. 2017 Jun;49(6):719.

- Ballesta B, Gonzalez H, Martin V, et al. Fatal ruxolitinib-related JC virus meningitis. J Neurovirol. 2017 Oct;23(5):783–785.

- Dioverti MV, Abu Saleh OM, Tande AJ. Infectious complications in patients on treatment with ruxolitinib: case report and review of the literature. Infect Dis. 2018 May;50(5):381–387.

- Reoma LB, Trindade CJ, Monaco MC, et al. Fatal encephalopathy with wild-type JC virus and ruxolitinib therapy. Ann Neurol. 2019 Dec;86(6):878–884.

- Caocci G, Murgia F, Podda L, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection following ruxolitinib treatment in a patient with myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2014 Jan;28(1):225–227.

- Shen CH, Hwang CE, Chen YY, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation associated with ruxolitinib. Ann Hematol. 2014 Jun;93(6):1075–1076.

- Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991 Jan;100(1):182–188.

- Yeo W, Chan PK, Ho WM, et al. Lamivudine for the prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B s-antigen seropositive cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. J. Clin Oncol: Offic J Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 1;22(5):927–934.

- Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and prophylaxis during solid tumor chemotherapy: A systematic Review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jan 5;164(1):30–40.

- Huang YH, Hsiao LT, Hong YC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of entecavir prophylaxis for rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B. J Clin Oncol: Offic J Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2013 Aug 1;31(22):2765–2772.

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 1;366(9):799–807.

- Hammond SP, Chen K, Pandit A, et al. Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2018 Apr 26;131(17):1987–1989.

- Duan M, Zhou D. Improvement of the hematologic toxicities of ruxolitinib in patients with MPN-associated myelofibrosis using a combination of thalidomide, stanozolol and prednisone. Hematology. 2019 Dec;24(1):516–520.

- Tur-Kaspa R, Burk RD, Shaul Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus DNA contains a glucocorticoid-responsive element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986 Mar;83(6):1627–1631.

- Chou CK, Wang LH, Lin HM, et al. Glucocorticoid stimulates hepatitis B viral gene expression in cultured human hepatoma cells. Hepatology. 1992 Jul;16(1):13–18.

- Carson P, Hong CJ, Otero-Vinas M, et al. Liver enzymes and lipid levels in patients with lipodermatosclerosis and venous ulcers treated with a prototypic anabolic steroid (stanozolol): a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015 Mar;14(1):11–18.