ABSTRACT

Objectives

To compare the efficacies and costs between pegfilgrastim and filgrastim prophylaxis for FN post-ASCT for lymphoma and multiple myeloma patients.

Methods

43 patients who received pegfilgrastim (6 mg) were compared to a retrospective cohort of 129 patients that had received filgrastim post-ASCT. Hematopoietic recovery time, FN incidence and treatment costs were assessed and compared.

Results

The mean time to absolute neutrophil count engraftment was 8.72 ± 2.38 days for the prospective pegfilgrastim group and 9.87 ± 3.13 days for the retrospective filgrastim group (P = 0.027). The incidence of FN was 18.60% and 50.39% in prospective pegfilgrastim and retrospective filgrastim groups, respectively (P = 0.000). The mean cost of filgrastim was $617.22 ± 37.87, compared with $525.78 for pegfilgrastim (P = 0.032).

Discussion

Convenience, effectiveness, and safety of prophylaxis for FN in the prospective pegfilgrastim group were significantly improved compared to the retrospective filgrastim group in ASCT patients.

Conclusion

Pegfilgrastim prophylaxis was more effective and convenient than filgrastim for FN prophylaxis in patients post-ASCT, especially for MM patients.

Introduction

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is a primary treatment for lymphoma and multiple myeloma (MM) patients that significantly improves overall survival of these patients. Treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor(G-CSF) post-ASCT could accelerate neutrophil engraftment and reduce intravenous antibiotic use, and time spent in the hospital [Citation1] – These treatment effects result in cost reductions [Citation2–4]. However, filgrastim treatment increases the pain experienced by transplant patients and increases the risk of infection and bleeding at the injection site. The increased half-life of pegfilgrastim is provided by PEG-sialic acid derivatives of filgrastim and is administrated once per chemotherapy cycle. The safety and efficacy of once-per-chemotherapy cycle pegfilgrastim are similar to daily filgrastim administered under various conditions [Citation5]. However, it has not been confirmed that pegfilgrastim prophylaxis is an effective alternative for daily filgrastim therapy for febrile neutropenia (FN) in ASCT patients [Citation6–9]. In this study, we compare the efficacies, safeties, and costs of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim prophylaxis for FN post-ASCT.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020, 43 lymphoma and MM patients who received ASCT were selected for pegfilgrastim prophylaxis post-ASCT. Inclusion criteria for patients were: 18–60 years of age; normal function of liver, renal, and heart function; and ineligibility for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Exclusion criteria for patients were: active infections before ASCT, pregnancy, and mental disease diagnosis. The outcomes of the cohort of 43 pegfilgrastim-treated patients were compared to those of a retrospective control group of 129 patients selected from our database that received ASCT between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2019. The 129 retrospective patients had received daily filgrastim treatment starting on the first day of agranulocytosis (ANC<1 × 109cells/L) post-ASCT. The filgrastim control group was similar in baseline characteristics to the prospective pegfilgrastim group in sex, age, diagnosis, disease status before ASCT, prior therapy lines, and mononuclear and CD34+cells. All patients provided informed consent, and the IRB of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University approved the study.

Conditioning regimen and transplantation

Conditioning regimens consisted of BEAM[Citation10] (12 cases in prospective pegfilgrastim group and 26 cases in retrospective filgrastim group), BEAC[Citation11] (18 cases in pegfilgrastim group and 48 cases in retrospective filgrastim group), or a single dose of melphalan (200 mg/m2)[Citation12] (13 cases in pegfilgrastim group and 55 cases in retrospective filgrastim group). Stem cell transplantation was performed as described previously [Citation13]

Pegfilgrastim and filgrastim prophylaxis

The 43 prospective pegfilgrastim patients were treated with pegfilgrastim (Jinyouli, Shiyao Co, LTD, P.R.China) (6 mg, subcutaneous) 4–6 h post-ASCT. Neutropenia was diagnosed when the ANC value was less than 0.5 × 109cells/L. The retrospective filgrastim group was administered filgrastim (10 ug/kg/d, Ruibai, Qilu Co, LTD, P.R.China) on the first day of ANC value was less than 1 × 109cells/L post-ASCT until ANC increased to more than 0.5 × 109cells/L for 3 consecutive days or 10 × 109cells/L for 1 d. Thrombopoietin 300U/kg was administered post-ASCT when the platelet count was below 50 × 109cells/L until the platelet count was greater than 75 × 109cells/L without the need for platelet transfusion. ANC recovery was confirmed when the ANC was equal to or greater than 0.5 × 109cells/L for 3 consecutive days without G-CSF. Platelet recovery was confirmed when the platelet count was equal to or greater than 20 × 109cells/L for 7 days without the need for platelet transfusion.

Detection, prevention and treatment of infection

All patients were given drugs for prevention of infection included acyclovir (250 mg b.i.d., intravenous, then orally as soon as feasible), with oral antifungal posaconazole(200 mg in 5 ml, t.i.d.) or voriconazole (200 mg, q12 h), and sulfamethoxazole tablets (960 mg b.i.d.) from the beginning of conditioning to day 30 post-ASCT. The cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr virus DNA, serum β-d-glucan and galactomannan were weekly screened. Carbapenem treatment (1 g, q8 h) was initiated if there was a fever above 38.3°C one time or a fever above 38°C for three hours post-ASCT. If the fever persisted beyond 3 days, a gram-positive cocci antibiotic, Teicoplanin (400 mg, q12 h) was included and oral antifungal administration was changed to intravenous antifungal drugs, such as caspofungin or voriconazole. Intravenous antibacterial drugs were discontinued when the ANC was equal to or greater than 5 × 108cells/L for 3 days post-ASCT and body temperature was normal for more than 3 days. If two consecutive positive surveillance of cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr virus DNA, ganciclovir or foscarnet sodium antiviral was given. The invasive fungal infection was treated according to EORTC/MSG Consensus [Citation14].

Outcomes

Neutropenia, FN, and cost of pegfilgrastim or filgrastim were compared between the two groups. Neutropenia was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE), version 3. Febrile neutropenia(FN)was defined as a single oral temperature of ≥38.3°C or a temperature of ≥38.0°C sustained for >1 h and an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <500 cells/mm3, or an ANC that was expected to decrease to <500 cells/mm3 over the next 48 h.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0. Outcome data were reported as a mean or as rate values and were verified using the t-test or chi-square test. The significance threshold was set to < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the two cohorts

The characteristics of the two cohorts were showed in . No significant differences were observed in gender, age, diagnosis, disease status before ASCT, and prior therapy lines between the two groups (P>0 .05).The impact factors of CD34+ cell dose of infused graft, plerixafor use in the mobilization and graft cellular content, which may have an impact on hematologic recovery, were comparable between two groups. (P>0 .05).

Table 1. Cohort characteristics.

Hematopoietic recovery

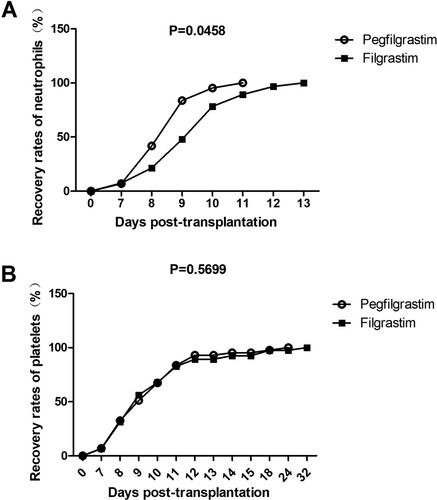

All patients recovered normal hematopoietic function post-ASCT. The mean time to absolute neutrophil count engraftment was 8.72 ± 2.38 days for the prospective pegfilgrastim group and 9.87 ± 3.13 days for the retrospective filgrastim group (P = 0.027) (A). Significant differences in mean time to platelet recovery between the two groups were not observed (P = .671). (B).

Neutropenia duration and febrile neutropenia incidence

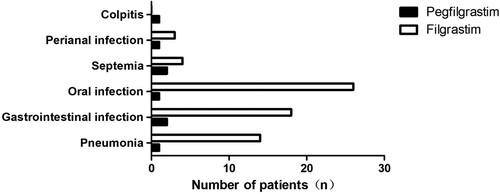

Th mean neutropenia duration was 5.03 ± 1.08 days for the prospective pegfilgrastim group and was 6.82 ± 1.34 days for the retrospective filgrastim group (P = 0.037). In the subgroup analysis for lymphoma or myeloma, the mean neutropenia duration of the pegfilgrastim-treated patients was also shorter than that of the filgrastim-treated patients (P = 0.025 for myloma patients and P = 0.042 for lymphoma patients).The incidence of FN was 18.60% (8/43) and 50.39% (65/129) in prospective pegfilgrastim and retrospective filgrastim groups, respectively (). The causes of fever are presented in . The groups demonstrated no significant difference in viral infection rates (P = 0.737). The number of patients with bacteriemia or fungal infection was lower in prospective pegfilgrastim compared with the retrospective filgrastim group (P = 0.002) ().

Table 2. Infections complications in two groups.

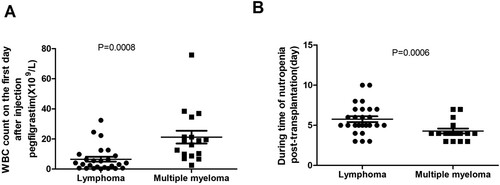

The white blood cell count of pegfilgrastim-treated MM patients on day 1 post-injection was significantly higher than the white blood cell count in pegfilgrastim-treated lymphoma patients (P < 0.05) (A). Mean neutropenia duration was 5.77 ± 1.12 days for pegfilgrastim-treated lymphoma patients and was 4.29 ± 1.03 days for pegfilgrastim-treated MM patients (P < 0.029) (B). There was no significant difference between the incidence of FN in MM patients(11.76%, 2/17) and lymphoma patients (23.08%,6/26) (P = 0.351).

Adverse reaction

The administration of pegfilgrastim or filgrastim treatments was well-tolerated among patients. One patient was treated with Tylox and glucocorticoid for bone pain and apnea after pegfilgrastim-treatment. Of the patients in the filgrastim group, 75.2% (97/129) developed purpura at the injection site. There were no other adverse reactions post-filgrastim administration.

Cost analysis

The drug prices are reported for the year 2020 and were used as the basis for the cost analysis. For the retrospective filgrastim group, the median cost was $617.22 ± 37.87 per patient, and for the prospective pegfilgrastim group, it was $525.78(P = 0.032). The costs of the hospital stay, pegfilgrastim or filgrastim, antibiotics or antifungal drugs, and blood products resulted in an additional expenditure of $7 for patients receiving filgrastim using the integrated cost analysis (P = 0.046) ().

Table 3. Cost analysis in two groups.

Discussion

Single-dose pegfilgrastim per chemotherapy cycle is as safe and effective as once-a-day filgrastim injections [Citation15–18].It has been reported that a single dose of pegfilgrastim was comparable to filgrastim in terms of the timing and efficacy of PBSC harvest before HSCT [Citation19]. However, it has not been confirmed that pegfilgrastim prophylaxis is an effective alternative for daily filgrastim therapy for febrile neutropenia (FN) in ASCT patients. Wannesson, et al. [Citation20] found that neutrophil engraftment time was reduced in pegfilgrastim-treated MM or lymphoma patients compared to those treated with daily filgrastim. However, fever duration was equivalent between the test and control groups. P Musto, et al reported that pegfilgrastim administered on the third day post-ASCT and daily filgrastim starting on the fifth day post-ASCT demonstrated similar safety and efficacy profiles [Citation21]. Jagasia et al. [Citation22]confirmed that single-dose per chemotherapy cycle pegfilgrastim beginning 24 h post-ASCT had safety profiles and neutrophil engraftment times similar to daily filgrastim initiated on the first or fourth day, but the incidence of FN was lower (49%) for the pegfilgrastim group patients [Citation22]. Vanstraelen et al. [Citation23] reported similar times to neutrophil, erythroid, or platelet engraftment, or incidences of fever or infection between pegfilgrastim and filgrastim treatments initiated at different times post-ASCT.In our study, the mean time to absolute neutrophil count engraftment was shorter in the prospective pegfilgrastim group compared to the retrospective filgrastim group. A significantly reduced incidence of FN was observed in the prospective pegfilgrastim group (18.60%) compared to the filgrastim-treated group (50.39%). This result may be due to unforeseen differences in the timing of G-CSF derivatives used.

The efficacy of neutropenia prophylaxis may be different for G-CSF derivatives used and different diseases [Citation24–26]. Ding et al. [Citation27] report that the average recovery time of leukocytes and platelets post-ASCT was shorter in pegfilgrastim-treated myeloma patients compared to filgrastim-treated myeloma patients. In our study, we also found the same results that MM patients treated with pegfilgrastim had a shorter duration of neutropenia compared to filgrastim-treated myeloma patients. The mean neutropenia duration of pegfilgrastim-treated myeloma patients was also shorter than that in pegfilgrastim-treated lymphoma patients.

The costs of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim treatments are similar in some studies [Citation28–30]. Delaying administration of G-CSF until the fifth or sixth day post-ASCT results in neutrophil recovery times similar to pegfilgrastim and reduces the cost of filgrastim compared to pegfilgrastim. Our study showed that when a conventional dosage of 10 ug/kg is administered starting on the first day of ANC post-ASCT, the median cost of filgrastim treatment was $617.22 ± 37.87 compared with $525.78 for pegfilgrastim. Different results may be due to the various administration times for filgrastim in different studies [Citation29].

This study also has two important limitations. It wasn’t a random prospective control study and there was study size discrepancy between filgrastim and pegfilgrastim groups. Thus, it needed to be further investigated by random prospective clinical trial.

Conclusion

We conducted a single-center retrospective analysis of lymphoma and MM patients undergoing pegfilgrastim or filgrastim post-ASCT. Our study demonstrated that pegfilgrastim prophylaxis was more effective and convenient than filgrastim for FN prophylaxis in patients post-ASCT, especially for MM patients.

Acknowledgments

X.W. and P.H. developed the data-analysis. X.W. wrote the manuscript. J.R. and X.L. treated patients and collected and analyzed data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ziakas PD, Kourbeti IS. Pegfilgrastim vs. filgrastim for supportive care after autologous stem cell transplantation: can we decide? Clin Transplant. 2012;26(1):16–22.

- Potter A, Beck B, Ngorsuraches S. Tbo-filgrastim versus filgrastim for stem cell mobilization and engraftment in autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: A retrospective review. J Oncol Pham Pract. 2020 Jan;26(1):23–28.

- Restelli U, Croce D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Monocentric analysis of the effectiveness and financial consequences of the Use of lenograstim versus filgrastim for mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells in patients with Lymphoma and Myeloma receiving chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. J Blood Med. 2020 Apr 2;11:123–130.

- Gardellini A, Gigli F, Babic A, et al. Filgrastim XM02 (tevagrastim) after autologous stem cell transplantation compared to lenograstim: favourable cost-efficacy analysis. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013 Jun 25;7:327.

- Rifkin R, Spitzer G, Orloff G, et al. Pegfilgrastim appears equivalent to daily dosing of filgrastim to treat neutropenia after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010 Jun;10(3):186–191.

- Gerds A, Fox-Geiman M, Dawravoo K, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim after autologus peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010 May;16(5):678–685.

- Castagna L, Bramanti S, Levis A, et al. Pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell support. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jul;21(7):1482–1485.

- Ballestrero A, Boy D, Gonella R, et al. Pegfilgrastim compared with filgrastim after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with solid tumours and lymphomas. Znn Hematol. 2008;87(1):49–55.

- Samaras P, Buset EM, Siciliano RD, et al. Equivalence of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim in lymphoma patients treated with BEAM followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. Oncology. 2010;79(1-2):93–97.

- Vidriales B, del Canizo MC, Corral M, et al. BEAM chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell support in lymphomapatients: analysis of efficacy, toxicity and prognostic factors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997 Sep;20(6):451–458.

- Robinson SP, Boumendil A, Finel H, et al. High-dose therapy with BEAC conditioning compared to BEAM conditioning prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin lymphoma: no differences in toxicity or outcome. A matched-control study of the EBMT-lymphoma Working party. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018 Dec;53(12):1553–1559.

- Auner HW, Iacobelli S, Sbianchi G, et al. Elphalan 140 mg/m(2) or 200 mg/m(2) for autologous transplantation in myeloma: results from the collaboration to collect autologous transplant outcomes in Lymphoma and Myeloma (CALM) study. A report by the EBMT chronic malignancies Working party. Haematologica. 2018;103(3):514–521.

- Wang X, Zhang Y, Fan T, et al. Effective mobilization with etoposide and cyclophosphamide for collection of peripheral blood stem cell in patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Invest Med. 2020 Sep 24;43(3):E27–E32.

- De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the european organization for research and treatment of cancer/invasive fungal Infections cooperative group and the National Institute of allergy and infectious diseases mycoses study group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 15;46(12):1813–1821.

- Moore DC, Pellegrino AE. Pegfilgrastim-Induced Bone pain: A review on incidence, risk factors, and evidence-based management. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(9):797–803.

- Bond TC, Szabo E, Gabriel S, et al. Meta-analysis and indirect treatment comparison of lipegfilgrastim with pegfilgrastim and filgrastim for the reduction of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia-related events. J OncolPharm Pract. 2018 Sep;24(6):412–423.

- Kataoka T, Sakurashita H, Taogoshi T, et al. Comparison of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim for the primary prophylactic effect for preventing febrile neutropenia in patients undergoing rituximab with dose-adjusted EPOCH chemotherapy. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2019;139(4):629–633.

- Kim MG, Han N, Lee EK, et al. Pegfilgrastim vs filgrastim in PBSC mobilization for autologous hematopoietic SCT: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015 Apr;50(4):523–530.

- Abid MB, De Mel S, Abid MA, et al. Pegylated filgrastim versus filgrastim for stem cell mobilization in multiple myeloma after novel agent induction. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(3):174–179.

- Wannesson L, Luthi F, Zucca E, et al. Pegfilgrastim to accelerate neutrophil engraftment following peripheral blood stem cell transplant and reduce the duration of neutropenia, hospitalization, and use of intravenous antibiotics: a phase II study in multiple myeloma and lymphoma and comparison with filgrastim-treated matched controls. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(3):436–443.

- Musto P, Scalzulli PR, Melillo L, et al. Peg-Filgrastim after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in hematological malignancies. Blood. 2004;104:384b.

- Jagasia MH, Greer JP, Morgan DS, et al. Pegfilgrastim after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant: phase II study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2005;35(12):1165–1169.

- Vanstraelen G, Frere P, Ngirabacu MC, et al. Pegfilgrastim compared with filgrastim after autologous hematopoietic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Exp HematoL. 2006;34(3):382–388.

- Bassi S, Rabascio C, Nassi L, et al. A single dose of pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim to evaluate the mobilization and the engraftment of autologous peripheral hematopoietic progenitors in malignant lymphoma patients candidate for high-dose chemotherapy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2010 Dec;43(3):321–326.

- Samaras P, Blickenstorfer M, Siciliano RD, et al. Pegfilgrastim reduces the length of hospitalization and the time to engraftment in multiple myeloma patients treated with melphalan 200 and auto-SCT compared with filgrastim. Ann Hematol. 2011;90(1):89–94.

- Martino M, Pratico G, Messina G, et al. Pegfilgrastim compared with filgrastim after high-dose melphalan and autologous hematopoietic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients. Eur J Haematol. 2006;77(5):410–415.

- Ding X, Huang W, Peng Y, et al. Pegfilgrastim improves the outcomes of mobilization and engraftment in autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2020 Jun;99(6):1331–1339.

- Kahl C, Sayer HG, Hinke A, et al. Early versus late administration of pegfilgrastim after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar;138(3):513–517.

- Cesaro S, Nesi F, Tridello G, et al. A randomized, non-inferiority study comparing efficacy and safety of a single dose of pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in pediatric patients after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53252.

- Sebban C, Lefranc A, Perrier L, et al. A randomised phase II study of the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim after autologous stem cell transplant for lymphoma and myeloma (PALM study). Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(5):713–720.