ABSTRACT

Objectives

Patterns and predictors of relapse in primary gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) were variably reported. Our study aims to evaluate the patterns and predictors of relapse in early-stage gastric DLBCL treated with Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisolone (RCHOP).

Methods

From 2005 to 2019, the medical records of 72 patients with stage I or stage II gastric DLBCL treated with six cycles of RCHOP without radiotherapy were reviewed. Different variables were correlated with progression free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and local relapse free survival (LRFS).

Results

64 (88.1%) patients achieved a complete response (CR), while 8 (11.9%) had refractory disease. After CR, 9 (14%) patients relapsed; 7 (78%) relapses were loco-regional. Abnormal LDH (p = 0.028), H. pylori negative (p = 0.032) and, stage adjusted international prognostic index (sa-IPI) > 1 (p = 0.013) correlated with loco-regional failure. The 5-year PFS, OS, and LRFS were 74.8%, 75.3%, and 87.5%, respectively, after a median follow-up of 58 (range: 6–185) months. The median time to progression or relapse was 9 months (range: 5–54 months). In multivariate analysis, a sa-IPI >1 (HR: 3.56, CI: 1.35–8.8, p = 0.01) was associated with PFS while low albumin (HR: 8.85, CI: 1.09–71.4, p = 0.041) was associated with worse OS. None of the variables were associated with LRFS.

Conclusion

Treatment of primary gastric DLBCL with RCHOP results in a high CR rate. The majority of treatment failures were loco-regional. Sa-IPI and H. pylori status may be used to identify patients who may benefit from combined modality treatment.

Introduction

The most common extranodal lymphoma is gastric lymphoma, which accounts for 30–40% of all extranodal lymphomas and 55–65% of gastrointestinal lymphomas [Citation1,Citation2]. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents 45–60% of all gastric lymphomas [Citation2,Citation3]. Although patients with gastric DLBCL typically present with nonspecific symptoms mimicking gastritis, approximately 60% are diagnosed with an early-stage disease [Citation4].

In early-stage DLBCL, SWOG trial established that either three cycles of rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (RCHOP) followed by radiotherapy or six cycles of RCHOP as the standard frontline treatments [Citation5,Citation6]. More recently, in patients with non-bulky disease, the stage-adjusted international prognostic index (sa-IPI) and response on PET-CT scan were used to select patients for the omission of radiotherapy or reduction in the number of chemotherapy administrations [Citation7,Citation8].

Although most gastric DLBCL patients treated with RCHOP achieve a complete response, 20–30% would relapse [Citation9,Citation10]. Relapse in gastric DLBCL is more frequently localized [Citation9], as opposed to most early-stage DLBCL, where relapse usually occurs at distant sites from the primary tumor [Citation11]. Factors that may correlate with relapse have been variably reported in different studies [Citation10,Citation12]. Most of these studies included patients with advanced-stage disease and used different chemotherapy regimens.

The role of consolidative radiotherapy in gastric DLBCL is still debatable. Decisions can be based on the post-chemotherapy PET-CT response, though discordance between the PET-CT response and the endoscopic response has been reported [Citation13].

In addition, the role of routine endoscopic examination in the follow-up of gastric DLBCL is not well-defined. Considering that most relapses are localized and symptoms are usually nonspecific, endoscopic surveillance may be justified. On the other hand, endoscopy and biopsy are procedures that are not without complications, may increase patients’ anxiety and burden on the endoscopy unit.

The purpose of this study is to look at predictors and patterns of relapse in patients with early-stage gastric DLBCL who have received at least six cycles of RCHOP without radiotherapy.

Patients and methods

Patients with a diagnosis of stage I or stage II (including stage II1, II2, and IIE) gastric DLBCL treated with at least six cycles of RCHOP without radiotherapy at King Hussein Cancer Center (KHCC) from 2005 until 2019 were identified, and data were extracted retrospectively using our hospital database and electronic medical records. Patients with distant nodal or other extranodal involvement were excluded. Initial presenting symptoms, laboratory investigations, endoscopic, and imaging findings were collected. Patients were staged with CT scan from 2005 until 2012 (n = 36) and with, CT and PET-CT scans after 2012 (n = 36). In addition, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and a bone marrow biopsy were done for all patients. The stage was defined according to the Lugano classification for gastrointestinal lymphoma [Citation14]. Multiple gastric lesions were defined as the presence of two or more distinct lesions on the EGD. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection was confirmed only by histological examination, as a C-Urea breath test wasn’t routinely done. Patients with H. pylori infection were treated with amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and a proton pump inhibitor.

The evaluation of response was based on post-treatment imaging (CT scan and/or PET-CT scan) and EGD. Patients who achieved a complete response (CR) were evaluated every three months for the first two years, then every six months thereafter, with a history, clinical examination, CT scan, and EGD.

The sa-IPI was calculated based on age, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), eastern cooperative oncology group (ECOG) performance status, and stage (I vs. II or IIE) as previously described [Citation5]. ECOG performance status was excluded from the analysis because one patient had an ECOG performance status of >1. Loco-regional failure (LRF) was defined as a refractory disease or relapse limited to the stomach and/or regional lymph nodes. Progression free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis until the end-of-treatment for refractory disease, progression of disease, or relapse. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to death. Local relapse free survival (LRFS) was defined as relapse in the stomach or regional lymph nodes after achieving a CR.

Continuous data were presented as median and interquartile range, while nominal data were presented as numbers and percentages. The associations between different variables and PFS, OS, and LRFS analyzed using the Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test in the univariate analysis and the Cox proportional hazard models in the multivariate analysis. Patients’ characteristics and LRF were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Survival outcomes were calculated using the Kaplan Meier method. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Seventy-two patients were included in the analysis, with a median age of 54 (range: 20–79) years. 41 (61%) patients were males. One-third were 60 years of age or older. The majority (83%) of the patients presented with abdominal pain. LDH was high in one-third. Initial EGD findings were ulcers only in 20 patients (27.8%) and a mass or an ulcerating mass in the rest of the patients. Thirteen (18%) patients had more than one gastric lesion. H. pylori was positive in 14 (19.4%) patients. 39 (54.2%) patients had stage I disease. Sa-IPI was >1 in 23 (31.9%) patients. Patients’ characteristics are detailed in .

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

Response and relapse

After completion of RCHOP, 64 patients (88.1%) achieved a CR, and 8 (11.9%) had a refractory disease that was limited to the stomach in six patients and to the stomach and regional lymph nodes in two patients. In addition, 9 (14%) patients experienced a relapse following a CR; 7 (78%) of these were loco-regional (seven in the stomach, one in the stomach, and regional lymph nodes), and 2 (22%) were distant (bone marrow and central nervous system). It is interesting to note that one patient had a gastric relapse after 54 months with H. pylori-negative mucosa associated lymphoid tissue tumor (MALT) that wasn’t detected at the initial biopsy, treated with radiotherapy, and was still alive and disease-free at the time of last follow-up.

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 1, 2 years, and 3 years was 15.3%, 19.5%, and 22.9%, respectively. The median time to relapse or progression was 9 (range: 5–54) months. When different variables were analyzed for LRF, patients who had LRF compared to those who didn’t, had significantly higher frequencies of abnormal LDH (60% vs. 26.3%, p = 0.028), H. pylori negative status (100% vs. 24.6%, p = 0.032) and, sa-IPI >1 (60% vs. 24.6%, p = 0.013), .

Table 2. Correlation between different variables and locoregional failure.

Survival outcomes

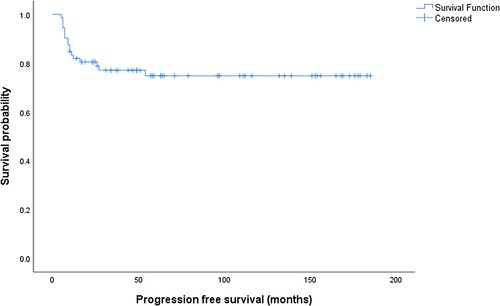

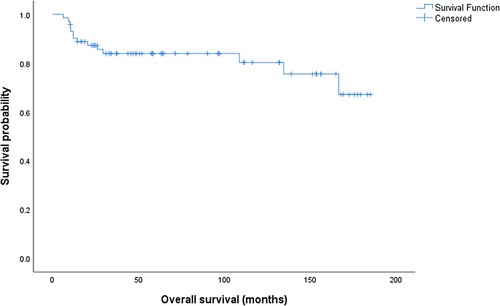

After a median follow-up of 58 (range: 6–185) months, the 5-year PFS was 74.8%, and 5-year overall survival was 75.3%, . Three of 14 deaths (21.4%) were related to ischemic heart disease, metastatic neuroendocrine tumor, and multiple myeloma, while 11 (78.6%) deaths were related to refractory gastric DLBCL.

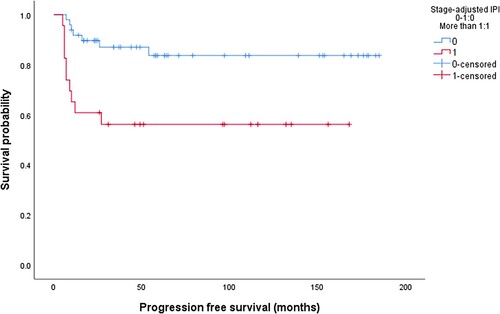

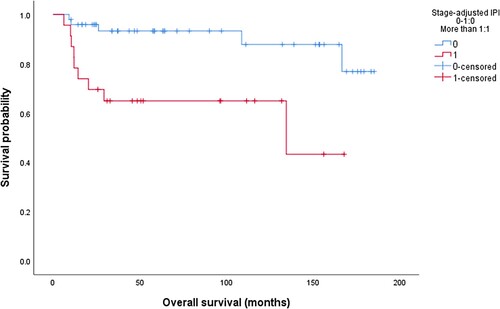

In univariate analysis, high LDH (p = 0.01), H. pylori negative status (p = 0.03) and sa-IPI > 1 (p = 0.004), , correlated with PFS, while OS correlated with high LDH (p = 0.011), low albumin (0.001), stage II (p = 0.02) and sa-IPI >1 (p = 0.001), , . In multivariate analysis, sa-IPI >1 (HR: 3.56, CI: 1.35-8.8, p = 0.01) correlated with PFS while low albumin (HR: 8.85, CI: 1.09–71.4, p = 0.041) was associated with a worse OS, . In the group of patients who achieved a CR (n = 64), the 5-year LRFS, PFS, and OS were 87.5%, 84.2%, and 72.7% respectively. None of the clinical, laboratory, or endoscopic variables significantly correlated with LRFS, .

Table 3. Univariate analysis.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis. Sa-IPI: stage-adjusted international prognostic index.

Salvage chemotherapy was given to 13 of 17 (74.5%) patients with relapse or refractory disease, 5 (38.4%) had a response and were treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Three patients (17.6%) had no disease at the time of the last visit, and two patients had passed away, one from relapse post-HSCT and the other because of ischemic heart disease.

Discussion

Due to the dearth of randomized controlled trials and the fact that gastric DLBCL differs from early-stage DLBCL in general in terms of its predictive variables and relapse patterns, there is still debate over the best frontline treatment.

In early-stage gastric DLBCL, our results supported the high CR rates, good LRFS, and PFS previously reported by other studies [Citation10,Citation15,Citation16]. The difference between our study’s 5-year OS rate and Kang et al results (75.3 vs. 87.4%) can be attributed to the fact that 3 out of 14 (21.4%) of our patients’ deaths were unrelated to disease or treatment, which Kang et al. did not mention [Citation10].

The sa-IPI has a well-established prognostic and predictive value in early-stage DLBCL as well as in gastric DLBCL [Citation17]. In the LYSA/GOELAMS trial, omission of radiotherapy was safe in patients with non-bulky early-stage DLBCL with a sa-IPI score of zero who achieved a complete metabolic response after four cycles of RCHOP [Citation7]. About 40% of patients had extranodal disease. Our results showed that sa-IPI correlated with PFS and predicted LRF, which may suggest that patients with sa-IPI > 1 may be considered for combined modality treatment while chemotherapy may be enough for patients with a low sa-IPI.

The correlation of H. pylori positivity with lower LRF in gastric DLBCL was also reported by other studies [Citation18–20]. Although the number of patients with H. pylori positive disease in our study is small (n = 14), 5-year PFS, OS, and LRFS rates of 100% are quite impressive. Possible explanations for this observation include immune cross-reactivity between H. pylori and malignant B lymphocytes [Citation21] and antigenic mimicry between H. pylori and gastric mucosa [Citation22]. Both effects would result in directing the immune response against H. pylori to malignant B lymphocytes and result in suppression of tumor progression or metastasis [Citation23]. Furthermore, in de novo gastric DLBCL, genome-wide sequencing revealed that the presence of H. pylori infection is associated with higher levels of miR-200, which can inhibit Zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) expression. ZEB1 expression is known to be associated with a worse prognosis in DLBCL [Citation20,Citation24]. This finding may justify the use of H. pylori status to select patients for treatment modification in a prospective trial.

It is clear that LRF predominates among all relapses in our study. All patients with documented refractory disease, and 78% of relapses in patients with a CR, were loco-regional. Earlier administration of radiotherapy after four cycles of RCHOP in patients with residual disease on interim evaluation may improve the outcomes [Citation25].

Low albumin levels have been linked to a poor prognosis in gastric DLBCL as well as other lymphomas [Citation10,Citation26,Citation27]. Hypoalbuminemia is an indicator of nutritional status that could be affected by the abnormal metabolic conditions induced by the tumor. This finding warrants further evaluation in a larger prospective trial.

It is difficult to identify patients who may benefit most from consolidative radiotherapy after achieving a CR. Different clinical, laboratory, and endoscopic features did not correlate with LRFS, mostly because of the small number of relapses. The presence of multiple gastric lesions, though did not correlate with LRFS in our study, was reported to correlate with LRFS [Citation9,Citation28]. In addition, the size and depth of tumor on endoscopic ultrasound may have a potential role in the selection of patients for consolidative radiotherapy [Citation29].

In our study, 86.7% of relapses were diagnosed within the first two years. This observation may suggest that endoscopic surveillance is appropriate within this time frame. However, further studies are needed to identify the patients who may benefit from routine endoscopic examinations after confirmation of CR.

The current standard treatment for relapsed or refractory DLBCL includes chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy for patients with refractory disease or early relapse (<12 months) [Citation30,Citation31], and salvage chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous HSCT for later relapses [Citation32]. Salvage radiotherapy can be considered for patients with localized relapse and may provide durable local control in up to two-thirds of patients [Citation33]. International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG) guidelines recommend the administration of radiotherapy to patients with localized refractory disease before or after HSCT, and with curative intention for locoregional refractory disease in transplant ineligible patients [Citation34]. Provided the small number of patients with relapsed or refractory disease in our study (n = 17), no firm conclusions can be made.

We admit that our study has important limitations, including the retrospective design, and the lack of cell of origin classification. In addition, the diagnosis of H. pylori infection was only made by histopathology as the use of the C-Urea breath test was not routinely performed.

Conclusion

The prognosis for primary gastric DLBCL treated with RCHOP is favorable. Loco-regional relapses made up the majority. The two main indicators of LRF were a Sa-IPI > 1 and an H. pylori negative status. The use of combined modality treatment may be considered for this group of patients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ghimire P, Wu GY, Zhu L. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb 14;17(6):697–707.

- Juárez-Salcedo LM, Sokol L, Chavez JC, et al. Primary gastric lymphoma, epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2018 Jan-Mar;25(1):1073274818778256.

- Koch P, Probst A, Berdel WE, et al. Treatment results in localized primary gastric lymphoma: data of patients registered within the German multicenter study (GIT NHL 02/96). J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct 1;23(28):7050–7059.

- Yang H, Wu M, Shen Y, et al. Treatment strategies and prognostic factors of primary gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A retrospective multicenter study of 272 cases from the China lymphoma patient registry. Int J Med Sci. 2019 Jun 10;16(7):1023–1031.

- Miller TP, Dahlberg S, Cassady JR, et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jul 2;339(1):21–26.

- Stephens DM, Li H, LeBlanc ML, et al. Continued risk of relapse independent of treatment modality in limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final and long-term analysis of southwest oncology group study S8736. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Sep 1;34(25):2997–3004.

- Lamy T, Damaj G, Soubeyran P, et al. R-CHOP 14 with or without radiotherapy in nonbulky limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018 Jan 11;131(2):174–181.

- Poeschel V, Held G, Ziepert M, et al. Four versus six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy in combination with six applications of rituximab in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma with favourable prognosis (FLYER): a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019 Dec 21;394(10216):2271–2281.

- Kang HJ, Lee HH, Jung SE, et al. Pattern of failure and optimal treatment strategy for primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2020 Sep 22;15(9):e0238807.

- Chihara D, Oki Y, Ine S, et al. Primary gastric diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL): analyses of prognostic factors and value of pretreatment FDG-PET scan. Eur J Haematol. 2010 Jun;84(6):493–498.

- Nijland M, Boslooper K, van Imhoff G, et al. Relapse in stage I(E) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2018 Apr;36(2):416–421.

- Delamain MT, da Silva MG, et al. Age-adjusted international prognostic index is a predictor of survival in gastric diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2016 Jul-Sep;38(3):247–251.

- Yoon SB, Lee IS, Lee HN, et al. Role of follow-up endoscopic examination in treatment response assessment for patients with gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016 Sep;51(9):1111–1117.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Sep 20;32(27):3059–3068.

- Tanaka T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of primary gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: a multicenter study of 95 patients in Japan. Ann Hematol. 2012 Mar;91(3):383–390.

- Kadota T, Seo S, Fuse H, et al. Complications and outcomes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with gastric lesions treated with R-CHOP. Cancer Med. 2019 Mar;8(3):982–989.

- Cortelazzo S, Rossi A, Roggero F, et al. Stage-modified international prognostic index effectively predicts clinical outcome of localized primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG). Ann Oncol. 1999 Dec;10(12):1433–1440.

- Cheng Y, Xiao Y, Zhou R, et al. Prognostic significance of helicobacter pylori-infection in gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2019 Aug 28;19(1):842.

- Kuo SH, Yeh KH, Chen LT, et al. Helicobacter pylori-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach: a distinct entity with lower aggressiveness and higher chemosensitivity. Blood Cancer J. 2014 Jun 20;4(6):e220–e220.

- Huang WT, Kuo SH, Cheng AL, et al. Inhibition of ZEB1 by miR-200 characterizes Helicobacter pylori-positive gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a less aggressive behavior. Mod Pathol. 2014 Aug;27(8):1116–1125.

- Negrini R, Savio A, Poiesi C, et al. Antigenic mimicry between Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa in the pathogenesis of body atrophic gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1996 Sep;111(3):655–665.

- Xue LJ, Su QS, Yang JH, et al. Autoimmune responses induced by Helicobacter pylori improve the prognosis of gastric carcinoma. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(2):273–276.

- Kuo SH, Chen LT, Lin CW, et al. Detection of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma cells: clinical and biological significance. Blood Cancer J. 2013 Jul 12;3(7):e125.

- Lemma S, Karihtala P, Haapasaari KM, et al. Biological roles and prognostic values of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition-mediating transcription factors Twist, ZEB1 and Slug in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Histopathology. 2013 Jan;62(2):326–333.

- Persky DO, Li H, Stephens DM, et al. Positron emission tomography-directed therapy for patients With limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of intergroup national clinical trials network study S1001. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Sep 10;38(26):3003–3011.

- Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin's disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin's Disease. 1998 Nov 19;339(21):1506–1514.

- Ngo L, Hee SW, Lim LC, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Before and after the introduction of rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(3):462–469

- Ishikawa E, Tanaka T, Shimada K, et al. A prognostic model, including the EBV status of tumor cells, for primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Cancer Med. 2018 Jul;7(7):3510–3520.

- Liu YZ, Xue K, Wang BS, et al. The size and depth of lesions measured by endoscopic ultrasonography are novel prognostic factors of primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Apr;60(4):934–939.

- Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):640–654.

- Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2022 Jul 16;400(10347):160]. Lancet. 2022;399(10343):2294–2308.

- Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(23):1540–1545.

- Tseng YD, Chen YH, Catalano PJ, et al. Rates and durability of response to salvage radiation therapy among patients with refractory or relapsed aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(1):223–231.

- Ng AK, Yahalom J, Goda JS, et al. Role of radiation therapy in patients With relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: guidelines from the international lymphoma radiation oncology group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(3):652–669.