ABSTRACT

Introduction

In Madagascar, the epidemiologic, therapeutic, and evolutionary aspects of multiple myeloma remain poorly understood. Our objectives were to describe the cases, report factors associated with mortality, and estimate patient survival.

Patients and method

This was a retrospective descriptive and analytical study conducted in five teaching hospitals in Madagascar: HJRA and CENHOSOA (Antananarivo), CHUPZAGA (Mahajanga), CHUAT (Toamasina) and CHUT (Fianarantsoa). The study included patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2021.

Results

Of the 11,374 cancer patients, 75 (0.66%) had multiple myeloma. The mean age of the patients was 59.9 years (±8.9) and the sex ratio was 1.5. Arterial hypertension was observed in 32% of the patients. The most common symptom of myeloma was bone pain (n = 48; 64%). Forty-six patients (61%) were diagnosed with stage III myeloma and 28 patients (37.3%) with stage IIIA myeloma according to the Durie-Salmon classification. Anemia, renal failure, hypercalcemia and fractures were present in 53%, 37%, 21% and 28% of cases, respectively. Fifty-four patients received specific treatment. The combination of melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide was used in 79.63% of cases, and one patient had received autologous stem cell transplantation. Eleven patients (14.67%) died. Chronic kidney disease (p = 0.009), smoking (p = 0.028) and two associated comorbidities (p = 0.035) were associated with mortality. The median overall survival was 45.5 months.

Conclusion

Patient survival is shorter than reported in the literature. The high mortality rate is due to comorbidities and limited access to recommended therapies.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the proliferation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, often accompanied by the secretion of monoclonal immunoglobulins and multivisceral failure. It accounts for 1% of all cancers and 15% of hematologic malignancies [Citation1]. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) 2020 data, there were approximately 176,404 new cases of MM worldwide [Citation2]. In the United States and France, the 5-year prevalence was estimated to be 27.63% and 28.25% per 100,000 individuals, respectively [Citation3,Citation4]. In Africa, the incidence was 4.8%, with higher frequencies in the western and northern regions [Citation2].

Research in MM has made real progress in recent years. Patient survival has improved, with median survival approaching six years [Citation5,Citation6]. This improvement is due to the availability of effective therapeutic agents, in particular immunomodulators and proteasome inhibitors, the concept of combination therapies and the advent of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) [Citation7].

In Madagascar, epidemiologic data are incomplete and patient outcomes remain poorly understood. A few single-center studies have been conducted in the capital [Citation8,Citation9]. We therefore considered it necessary conduct a multicenter study. Our objectives were to describe the epidemioclinical, paraclinical, therapeutic, and evolutionary aspects of MM, to report factors associated with mortality, and to estimate patient survival.

Patients and method

Characteristics of the study

This was a retrospective, descriptive and analytical multicenter study carried out in the oncology departments of five teaching hospitals in Madagascar.

Joseph Ravoahangy Andrianavalona University Hospital (HJRA) and Soavinandriana Hospital (CENHOSOA) in Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar and the chief town of the Analamanga region.

Professeur Zafisaona Gabriel University Hospital (CHUPZAGA) in Mahajanga, the capital of the Boeny region and capital of the former Northwest Province of Madagascar.

Analankininina University Hospital in Toamasina (CHUAT), the capital of the Antsinanana region and the main city of the former Eastern Province of Madagascar.

Tambohobe University Hospital (CHUT) in Fianarantsoa, the capital of the Matsiatra Ambony region.

The study involved patients who were hospitalized and followed in oncology departments over a 12-year period, from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2021. It has been carried out from the opening date for departments that became operational after 2010.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients diagnosed with MM and aged 18 years or older were included in the study. The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria, as revised in 2018, were used [Citation7]. The diagnosis of MM requires clonal bone marrow plasma cells ≥ 10% or biopsy-proven bony or extramedullary plasmacytoma and one or more myeloma defining events. The myeloma defining events consist of established CRAB features (hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, or bone lesions) as well as three specific biomarkers: clonal bone marrow plasma cells ≥ 60%, serum free light chain ratio ≥100 (provided the FLC level involved is _100 mg/L), and more than one focal lesion on magnetic resonance imaging [Citation7]. The International Staging System classification was not used because the beta-2-microglobulin test is very expensive and requires samples to be sent abroad. Therefore, the Durie-Salmon classification was used [Citation10].

Patients whose medical records were unusable due to missing information were excluded.

Studied parameters

Data were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records. Parameters studied were demographic characteristics, mode of MM presentation, biological and radiological features at initial evaluation, specific treatment of MM, and patient outcome. Comorbidities reported in the 10 years prior to MM diagnosis were assessed and included arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease (CKD), cancer, dementia, depression, epilepsy, chronic pancreatitis, cirrhosis, and autoimmune diseases.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were presented as means and/or medians. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test was used to assess factors associated with mortality (two-tailed test), and p-values below 0.05 were considered significant. The log-rank test was used to estimate patient survival, which was plotted on the Kaplan-Meier curve. Analysis was performed using Epi Info® version 7.2 and IBMTM SPSS® version 21 software.

Results

During the study period, 11,374 patients were hospitalized and followed up in oncology departments. Ninety patients were diagnosed with MM and 15 patients were excluded. A total of 75 patients were included (0.66%). The number of cases was one in 2010 and 59 in 2020. shows the number of cases reported in each hospital center in Madagascar.

Demographic characteristics

Forty-five patients (60%) were male, with a sex ratio of 1.5. The mean age at diagnosis was 59.9 years (±8.9), with a median of 60 years and extremes of 41 and 80 years. The age group [50–60] years was found in 38.7% of cases (n = 29) ().

Table 1. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics.

Antecedents and comorbidities

Forty-two percent of cases (n = 32) had at least one comorbidity. Thirty-two percent of cases (n = 24) had one comorbidity and 10.7% of cases (n = 8) had two associated comorbidities. Arterial hypertension was reported in 32% of cases (n = 24) (). Of the hypertensive patients, 14 (58.3%) were on antihypertensive treatment. Three patients had CKD and one was on chronic hemodialysis. Active smoking was found in 14.7% of the cases (n = 11).

Revelation modes

Osteoarticular pain was reported in 64% of cases (n = 48) (). Thirteen percent of the cases had no clinical symptoms.

Biological characteristics

shows the mean, median and extreme values of the biological parameters. Anemia was present in 53.3% of cases (n = 40), eight patients (10.7%) had hemoglobin levels < 6 g/dL and 32 patients (42.7%) had levels between 6 and 10 g/dL. Twenty-eight patients (37.3%) had renal failure. Hypercalcemia was found in 21.3% of cases (n = 16). Proteinuria was measured in 26 patients and was < 1 g/24H in 16, between 1 and 3 g/24H in two and ≥ 3 g/24H in eight patients. Lipid profiles were available for 19 patients. Eight patients had reduced HDL-c levels, two patients had hypertriglyceridemia, and one patient had both elevated LDL-c and hypercholesterolemia. Sixty patients had serum protein electrophoresis and a monoclonal peak was found in 73.3% of cases (n = 44). Immunofixation was performed in 24 patients and the monoclonal immunoglobulin was IgG in 16 patients (66.7%) ().

Table 2. Mean, median and extreme values of the biological parameters.

Table 3. Patient distribution by immunofixation electrophoresis.

Radiological findings

Radiologic findings included fractures (n = 21, 28%), diffuse osteolysis (n = 18, 24%), bone demineralization (n = 14, 18.7%), and geodes (n = 13, 17.3%). Fractures involved the spine (85.7%), femur (9.5%), and ribs (4.7%). Thirty-seven percent of patients had no abnormalities.

Durie-Salmon classification

MM was classified as stage III in the majority of cases (61.3%) (). Stage IIIA was observed in 28 patients (37.3%) and stage IIIB in 18 patients (24%).

Table 4. Patient distribution by Durie-Salmon classification.

Treatment

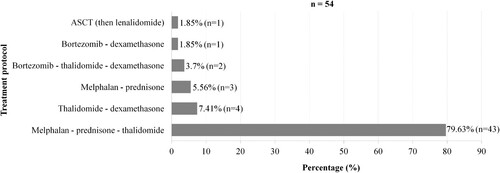

Fifty-four patients (72%) received a specific treatment. The combination of melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide (MPT) was used in 79.6% of cases (n = 43). One patient received ASCT (). The mean duration of specific treatment was 293.3 days (9 months), with a maximum of 1,086 days (36 months).

Evolution and survival

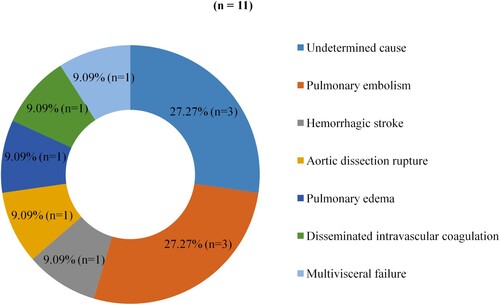

Forty-four patients (58.7%) were lost to follow-up and 11 patients died, resulting in a case-fatality rate of 14.7%. The case-fatality rate was 21.9% in comorbid patients versus 9.3% in non-comorbid patients. Cardiovascular complications were the leading cause of death (). shows the statistical evaluation of factors associated with mortality. CKD (p = 0.009), active smoking (p = 0.028) and the presence of two comorbidities (p = 0.035) were significantly associated with mortality.

Table 5. Evaluation of factors associated with mortality.

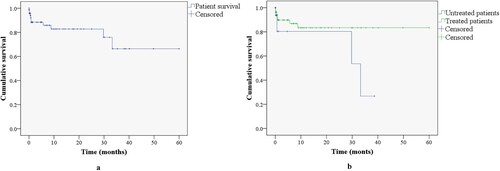

Median overall survival was 45.5 months (95%CI: 37.5-53.5) or 3.8 years. The majority of patients (n = 65, 86.7%) had a median survival of less than 30 months. Only one patient survived more than 60 months (154 months). Median survival was 50.6 months (95%CI: 44–57.1) and 27.3 months (95%CI: 18–36.7) for treated and untreated patients, respectively. shows the estimated survival curve through 60 months.

Discussion

Cases reported in Madagascar

Seventy-five patients diagnosed with MM were included. To our knowledge, no multicenter study has ever been conducted in Madagascar. In 2009, Andrianarison et al. reported 19 cases in a two-year prospective study [Citation8]. In 2018, Harioly et al. reported 48 cases in a 6-year retrospective study [Citation9]. In 2021, Ranaivomanana et al. reported eight cases out of 1,481 new cancer cases [Citation11]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, 55 cases were identified out of 20,681 new cancer cases [Citation12]. These observations show an increase in the incidence of MM diagnosed in recent years, which can be explained by improved diagnostic methods.

Patient demographic characteristics

The mean age of the patients was 59.94 years, which is similar to that reported in the Malagasy literature [Citation8,Citation9]. In African studies, the mean age was 66 years in Tunisia [Citation13], 57 years in Cameroon [Citation14] and 61.5 years in Morocco (El Ghali et al. 2021) [Citation13–15]. Young age is a particular feature of MM in the African population. In developed countries, MM affects people over 65 years of age. The median age at diagnosis is around 70 years, and 5–10% are younger than 50 years [Citation1,Citation16]. Improved health care and lower fertility are responsible for the aging of the population in developed countries. Older age is associated with a higher risk of MM [Citation17].

In terms of gender, the study showed a male predominance, similar to the Malagasy literature [Citation8,Citation9]. In the GLOBOCAN 2020 data, age-standardized incidence rates are significantly higher in men [Citation2]. The male predominance is similar to the literature [Citation13,Citation15,Citation16].

Patient comorbidities

Therapeutic advances have increased the life expectancy of patients who are more likely to have comorbidities. In the present study, 32 patients had comorbidities, a prevalence of 42.7%. This result is similar to the prevalence reported in Denmark (40.9%) by Gregersen et al. in a study of 2,190 cases in 2017 [Citation18]. In the Swedish Cancer Registry, 54.2% of patients had comorbidities, according to a 23-year study by Sverrisdóttir et al. published in 2021 [Citation16].

According to Gregersen et al, arterial hypertension is the most common comorbidity and age is the main risk factor [Citation18]. In our study, hypertension was found in 32% of the cases. In Sweden, the most common comorbidity was hypertension (20.4%) [Citation16]. In 2016, Chari et al. reported the same result in a registry of 8,000 patients [Citation19]. In addition, the proportion of treated hypertensive patients was 58.3%, while in other studies it was over 70% [Citation20]. It is important to identify and optimize the treatment of hypertension in patients.

Diabetes mellitus was found in 8% of cases, similar to the frequency reported in Sweden (8.38%) [Citation16]. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus at the time of MM diagnosis is around 16% and may increase to more than 30% after corticosteroid therapy [Citation21]. Diabetes must be systematically screened for at the time of MM diagnosis and prior to any specific treatment.

Four percent of cases had known CKD, as reported in the literature. Less than 6% of patients have pre-existing moderate to severe renal failure [Citation16,Citation18]. The presence of pre-existing renal disease in newly diagnosed MM may be due to cardiovascular comorbidities and nephrotoxic substances. It may also represent the revelation mode of the disease.

Multiple myeloma revelation modes

The clinical presentation of MM is polymorphic. Bone involvement is the most common and manifests as osteoarticular pain, reported in over 60% of cases [Citation9,Citation13–15]. Bone pain results from the destruction of bone tissue due to an imbalance between osteoclasts and osteoblasts. In the absence of symptoms, MM can be detected by biological tests. In our study, 13% of the cases had no clinical symptoms. According to the literature, 14% to 17% of cases are discovered incidentally [Citation13,Citation15]. However, MM is symptomatic if at least one of the CRAB criteria is present [Citation7].

Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia was found in 21.3% of cases. Similar results have been reported in Cameroon (26.9%) and Morocco (25%) [Citation14,Citation15]. Hypercalcemia is present in about 20% of patients at the time of diagnosis. It can be explained by hyperosteoclastosis, reduced renal function and increased tubular reabsorption of calcium [Citation22].

Renal failure

The incidence of renal failure at the time of MM diagnosis varies between 20% and 50% [Citation22]. In our study, renal failure was present in 37.3% of the cases. Harioly et al. reported a similar result (25%) [Citation9]. The frequency of renal failure in Malagasy patients is similar to that reported in the literature. The mechanism is mainly related to the toxic effects of light chains. The most common form is myelomatous tubulopathy (63–87%) [Citation22,Citation23].

Anemia

Anemia is commonly associated with MM and is reported in 97% of cases during the course of the disease. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 80% of cases have anemia [Citation24]. In our study, half of the cases (53.3%) presented with anemia and 10.7% had hemoglobin levels < 6 g/dL. Thus, anemia is less frequent and less severe. In addition to bone marrow failure, anemia may be due to an inflammatory syndrome, excessive iron consumption, hemorrhage, inhibition of erythropoiesis, or renal failure. Rarely, a hemolytic mechanism may occur [Citation22].

Bone lesions

Sixty-three percent of patients had bone abnormalities, which is similar to the study by Harioly et al (66.6%) [Citation9]. Bone lesions are characteristic of MM and occur in up to 80% of newly diagnosed patients [Citation25]. They are explained by bone resorption due to hyperosteoclastosis. In the literature, the radiologic findings consist mainly of osteolytic lesions with a low frequency of fractures [Citation7,Citation25]. In our study, fractures were the most common. This may reflect the neglect of bone pain by patients and possibly by clinicians. Neglected bone lesions develop into fractures, which may worsen the functional prognosis of the patient.

Immunological profile

In our study, a monoclonal peak was observed on serum protein electrophoresis in 73.3% of cases. The most common types were IgG (66.7%) and IgA (16.66%). No IgM cases were found. The light chains were kappa in 54.2% and lambda in 45.8% of cases. MM light chain was found in 12.5% of cases. In the literature, the monoclonal peak is observed in almost 80% of cases and its absence reflects either non-excreting MM or isolated light chain secretion [Citation26]. According to Kyle et al., MM is predominantly IgG, followed by IgA [Citation26]. IgM myeloma is very rare, as IgM monoclonal gammopathy is more likely to be a risk factor for Waldenström’s disease [Citation27]. The kappa type is the most common and light chain MM accounts for 10–20% of cases [Citation26]. The immunologic profile of our patients is similar to that reported in the literature.

Durie-Salmon classification

The Durie-Salmon classification was the first staging system to reflect tumor burden [Citation10]. It was later replaced by the International Staging System [Citation28]. Despite its high prognostic value, this new classification was not used in this study because the beta-2-microglobulin test is very expensive and requires samples to be sent abroad. Therefore, the old classification was used in our study. The majority of patients were diagnosed as stage III (61.3%), which corresponds to a high tumor mass, and stage IIIA was the most common (37.3%). In the study by Andrianarison et al, stage III was reported in 95% of cases, with a predominance of stage IIIB (68%) [Citation8]. The predominance of stage III correlates with delayed presentation and diagnosis. These results are similar to data from Africa, such as Tunisia (58.5%), Cameroon (60.61%) and Morocco (89.2%) [Citation13–15].

Multiple myeloma treatment

For transplant-eligible patients, the IMWG recommends a bortezomib-based regimen, ideally in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. For patients ineligible due to age or comorbidities, bortezomib or lenalidomide is recommended. Melphalan-based protocols should be avoided due to the risk of myelotoxicity [Citation7].

In Madagascar, the technical platform does not allow for ASCT. Patients must be evacuated to another country to receive this treatment. As first-line therapy, the combination of bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone is used in younger patients and the MPT combination in older patients. Access to bortezomib is very difficult due to its high cost. The MPT regimen remains the most accessible and widely used, as observed in our study. Our proportion of treated patients was 72%, compared to 80% in other studies [Citation13,Citation15]. These observations show that the management of MM is a major challenge in Madagascar.

Patient outcome and survival

Eleven patients died, giving a case fatality rate of 14.7%, with cardiovascular complications being the most common cause of death. This rate is not different from Tunisia (17.02%) and Morocco (11.5%) [Citation13,Citation15]. In contrast, the mortality rate in Cameroon was three times higher [Citation14]. In the literature, infectious causes precede cardiovascular causes [Citation20].

The median overall survival of our patients was 45.5 months (3.8 years) and 12% of patients survived between 30 and 60 months. In randomized studies, patient survival ranged from 6 to 10 years [Citation5]. As a result, the survival of our patients is shorter due to the limited accessibility of ASCT and innovative therapies and the often delayed diagnosis.

Factors associated with mortality

CKD was significantly associated with mortality. Sverrisdóttir et al. reported the same association [Citation16]. The presence of pre-existing CKD has an impact on patient survival. Early nephrological follow-up is necessary in patients with CKD at the time of MM diagnosis.

Smoking was significantly associated with mortality. Smoking is known to double the risk of death in myeloma patients [Citation20]. It is a cardiovascular risk factor and a predictor of underlying lung disease. Consequently, respiratory dysfunction increases morbidity and mortality in MM [Citation29]. Smoking cessation should be recommended to improve patient survival.

Patients with two associated comorbidities had a high mortality rate. Similar findings have been reported [Citation16]. The risk of mortality increases with the number of baseline comorbidities. Comorbidities may also multiply the risk of side effects of therapeutic agents. Identifying and optimizing comorbidities would help improve overall patient management.

Study strengths and limitations

This study has limitations. A major limitation is the use of the Durie-Salmon classification, which is somewhat outdated as a prognostic classification. The free light chain ratio was not available. This is one of the diagnostic criteria and is a factor in MM progression. Treatment discontinuation and response were not assessed in this study.

However, this study is the first multicenter study of MM in Madagascar. For the first time, the number of reported cases exceeds 60. It is the first to describe comorbidities in Malagasy patients diagnosed with MM and to show associations between comorbidities and mortality in this specific population. Further work is needed to examine patient outcomes and response to treatment.

Conclusion

MM is not uncommon but is underdiagnosed in Madagascar. Patients were young and mostly diagnosed at an advanced stage, reflecting delays in consultation and diagnosis. The association of two comorbidities, pre-existing CKD and smoking, were the factors associated with mortality. The survival of the patients was shorter and the treatment is far from the latest recommendations. Therefore, the search for comorbidities should be systematic when diagnosing MM. Early nephrologic consultation is recommended in patients with CKD. Smokers should be strongly encouraged to quit. Access to new therapeutic molecules should be facilitated through collaboration between health authorities and pharmaceutical laboratories or international non-governmental organizations. It is essential to improve the local technical platform to perform ASCT on the island.

Authors’ contributions

RMF Randrianarisoa: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, original drafting. V Refeno: conceptualization, methodology, writing-revision and editing. NOTF Andrianandrasana: writing-editing. F Ralison, HMD Vololontiana, F Rafaramino: visualization, validation.

Declaration of data availability

Additional data may be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the most recent ethical guidelines of the institution’s research committee. Patient anonymity was maintained.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the staff of the oncology departments of CHUJRA and CENHOSOA (Antananarivo), CHU PZAGA (Mahajanga), CHUAT (Toamasina) and CHUT (Fianarantsoa).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Kazandjian D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: a unique malignancy. Semin Oncol. 2016;43(6):676–681. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.11.004

- The Global Cancer Observatory. Multiple myeloma – GLOBOCAN 2020. [fact-sheets], [accessed 2023 February 23]. Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/35-Multiple-myeloma-fact-sheet.pdf

- The Global Cancer Observatory. United States of America – GLOBOCAN 2020 [fact-sheets]. [accessed 2023 February 23]. Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/840-united-states-of-america-fact-sheets.pdf

- The Global Cancer Observatory. France – GLOBOCAN 2020 [fact-sheets]. [accessed 2023 February 23]. Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/250-france-fact-sheets.pdf

- Durie BGM, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):519–527. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X

- Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111(5):2516–2520. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2018 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(8):981–1114. doi:10.1002/ajh.25117

- Andrianarison JFL, Ranoharison HD, Rakotoarivelo RA, et al. Myélome multiple chez les Malgaches. Hematologie. 2009;S1(15):74.

- Harioly Nirina MOM, Rasolonjatovo AS, Tsifanesy BG, et al. Description of 48 cases of multiple myeloma seen in the hematology laboratory of the CHU-Joseph Ravoahangy Andrianavalona, Antananarivo, Madagascar. Med Sante Trop. 2018;28(1):73–75. doi:10.1684/mst.2018.0763

- Durie BGM, Salmon SE. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma correlation of measured myeloma cell mass with presenting clinical features, response to treatment, and survival. Cancer. 1975;36(3):842–854. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197509)36:3<842::aid-cncr2820360303>3.0.co;2-u

- Ranaivomanana AHM, Hasiniatsy NRE, Randriamalala NCR, et al. Epidemiology of cancers at the oncology department of the Joseph Ravoahangy Andrianavalona Teaching Hospital of Antananarivo from 2009 to 2010. Revue Malgache de Cancérologie. 2021;5(1):194–210.

- The Global Cancer Observatory. Madagascar – GLOBOCAN 2020 [fact-sheets]. [accessed février 2023 23]. Avalaible at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/450-madagascar-fact-sheets.pdf

- Brahem M, Jguirim M, Klii R, et al. Myélome multiple : étude descriptive de 94 cas. Rev Med Interne. 2015;36(S2):A139–A140. doi:10.1016/j.revmed.2015.10.087

- Ngo Sack FF, Ngouadjeu E, Carre JL. Multiple myeloma epidemiological, clinical, paraclinical aspects: about 67 observations collected at the central hospital of Yaoundé and the general hospital of Douala. RAMReS Sciences de la Santé. 2017;5:2.

- Boufrioua EG, Mohammed O, Hicham Y, Mustapha AM, Chakour M. Le myélome multiple : les particularités diagnostiques, thérapeutiques et pronostiques de 123 cas colligés à l´Hôpital Militaire Avicenne de Marrakech. PAMJ Clin Med 2021; 5(70). doi:10.11604/pamj-cm.2021.5.70.20639

- Sverrisdóttir IS, Rögnvaldsson S, Thorsteinsdottir S, et al. Comorbidities in multiple myeloma and implications on survival: a population-based study. Eur J Haematol. 2021;106(6):774–782. doi:10.1111/ejh.13597

- Turesson I, Bjorkholm M, Blimark CH, et al. Rapidly changing myeloma epidemiology in the general population: increased incidence, older patients, and longer survival. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(2):237–244. doi:10.1111/ejh.13083

- Gregersen H, Vangsted AJ, Abildgaard N, et al. The impact of comorbidity on mortality in multiple myeloma: a Danish nationwide population-based study. Cancer Med. 2017;6(7):1807–1816. doi:10.1002/cam4.1128

- Chari A, Mezzi K, Zhu S, et al. Incidence and risk of hypertension in patients newly treated for multiple myeloma: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):912, doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2955-0

- Backs D, Saglam I, Löffler C, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and diseases in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Oncotarget. 2019;10(34):3154–3165. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.26872

- La L, Jagannath S, Ailawadhi S, et al. Clinical features and survival outcomes in diabetic patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) enrolled in the Connect® MM registry. Blood. 2020;136(1):49–50. doi:10.1182/blood-2020-137309

- Manier S, Leleu X. Multiple myeloma: clinical diagnosis and prospect of treatment. Recommendations of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG). Immunoanal Biol Spe. 2011;26(3):125–136.

- Dimopoulos MA, Sonneveld P, Leung N, et al. International Myeloma working group recommendations for the diagnosis and management of myeloma-related renal impairment. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1544–1557. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.0044

- Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21–33. doi:10.4065/78.1.21

- Moulopoulos LA, Koutoulidis V, Hillengass J, et al. Recommendations for acquisition, interpretation and reporting of whole body low dose CT in patients with multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a report of the IMWG Bone Working Group. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(10):95, doi:10.1038/s41408-018-0124-1

- Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: review of 869 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50(1):29–40.

- Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International myeloma working group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5

- Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3412–3420. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242

- Engelhardt M, Domm AS, Dold SM, et al. A concise revised Myeloma comorbidity index as a valid prognostic instrument in a large cohort of 801 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2017;102(5):910–921. doi:10.3324/haematol.2016.162693