Abstract

Little is known about the prevalence of gender-based violence (GBV) in sport in European Union (EU) Member States (MS). The research question underpinning this study was therefore: What is the nature and extent of gender-based violence in sport in the EU? The study involved a scoping exercise that mapped existing research on the incidence and/or prevalence of any/all form(s) of GBV in sport. This was complemented by interviews with key stakeholders within each EU MS. Forty-one studies were identified across 17 countries. Of these, none investigated the whole range of behaviours that constitute GBV, so the prevalence of GBV in sport in EU MS is unknown. The most commonly studied form of GBV was sexual harassment, which had a reported prevalence rate of between 1% and 64% due to different methodologies and definitions. This variation is indicative of the challenges of studying GBV, which are discussed in this paper. Without clear prevalence rates for of (all forms of) GBV, prevention efforts cannot be efficiently targeted and the effectiveness of interventions cannot be assessed. Among others, we recommend the European Commission contract regular research in sport that uses a standardised definition of GBV and a common methodological approach.

Gender-based violence in sport: an introduction

The first empirical work on violence in sport focussed on spectator violence (i.e. Case & Boucher, Citation1981; Williams et al., Citation1984). By the mid-1990s, following feminist critiques of male hegemony in sport (i.e. Hall, Citation1985; White & Brackenridge, Citation1985), researchers in the UK and North America began to expand this work to other forms of violence, specifically sexual violence such as sexual harassment and exploitation, against adult and child female athletes predominantly by male coaches (i.e. Brackenridge, Citation1994; Lenskyj, Citation1992). This work provided important insights into women’s and girls’ experiences of certain forms of gender-based violence (GBV) in sport and the impact on the proliferation, normalisation, and concealment of such violence on hegemonic masculinity and socio-cultural norms within sport.

Research has since expanded to other countries and other forms of violence, including and beyond forms of GBV, such as emotional and psychological abuse (Kerr et al., Citation2020; Yabe et al., Citation2019), physical abuse, early specialisation and intensive training (Lang, Citation2010a; McPherson et al., Citation2017; Oliver & Lloyd, Citation2015), bullying (Nery et al., Citation2020), homophobic abuse (Baiocco et al., Citation2018), and hazing (Jeckell et al., Citation2018). Studies have also explored the ways sports culture facilitates and normalises abusive practices and enforces athlete compliance with these (Lang, Citation2010b; Zehntner, Citation2020), and the implementation and impact of sexual violence-prevention approaches (Nurse, Citation2018; Rulofs et al., Citation2019). In sum, research on violence, including GBV, in sport has burgeoned, though much of the published work focuses on individual forms of GBV and notably those that receive the most media coverage, namely sexual abuse and harassment (Lang, Citation2021a). Research is also usually from single countries and often fails to acknowledge the violence in question is rooted in gender inequity. Meanwhile, despite a significant amount of data on the prevalence of violence in other contexts (i.e. domestic abuse, workplace harassment, school bullying), research investigating the prevalence of violence in sport, including GBV, remains relatively rare.

Studies of the prevalence of violence investigate the proportion of a population that experience violence during a specific period, while studies of incidence identify the number of new cases in a population within a specified period, usually one year (Pereda et al., Citation2009). Empirical work to understand the prevalence of GBV is crucial for several reasons. First, appropriate and effective policy responses to prevent and address GBV depend on an accurate understanding of its prevalence. If a prevalence study identifies that a particular form of GBV is a significant issue, for example, then it is clear that prevention and management initiatives are needed around this, allowing for efficient distribution of funds and efforts towards that topic. Once a baseline figure for the prevalence of GBV in sport is established, this can be monitored at regular intervals to determine whether or not the scale of the problem is increasing or decreasing, and the extent to which a particular intervention is effective. This tracking allows funders to distribute resources towards the most effective intervention strategies. As such, knowing the prevalence of GBV in sport is critical for government, policymakers, welfare professionals, and all sport stakeholders. Data on the prevalence of GBV in sport can also help convince sport stakeholders that the issue warrants attention. This is paramount given that, historically, sports organisations have been, at best, slow to respond to concerns about violence and abuse and, at worse, in denial about the issue and, as a result, reluctant to intervene (Brackenridge, Citation2001; Lang, Citation2021b). These factors mean that the collection of robust prevalence data on all forms of violence in sport, including GBV, is essential.

In recognition of the dearth of data regarding GBV, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Education and Culture requested in 2015 that the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA) launch a study to assess the nature and extent of GBV in sport in the EU (see European Commission, Citation2014). This paper reports the findings from this study, which was (and still is) the first to attempt to measure the scope of GBV in professional and grassroots sports across all (then) 28 EU Member States. Findings that critically assess developments in Member State’s national policy frameworks for GBV in sport have been published elsewhere (Lang et al., Citation2018). This paper reports on the challenges in collating and understanding research on the prevalence of GBV in sport before presenting research that has attempted to establish the magnitude of GBV and/or its forms in sport within Member States. First, we discuss the study itself and how the data was collected.

The study

The definition of GBV in the European Commission’s (Citation2014) Gender Equality in Sport: Proposal for Strategic Actions 2014–2020 was used in the study: ‘violence directed against a person because of that person’s gender (including gender identity/expression) or violence that affects persons of a particular gender disproportionately’ (European Commission, Citation2014, p. 47). Several forms of GBV were considered: verbal, non-verbal, physical, and sexual harassment and abuse. These forms are not mutually exclusive but overlapping categories. The study investigated GBV in the coach-athlete relationship, the entourage of the sport-athlete relationship (e.g. officials, doctors, physiotherapists), and the peer athlete-athlete relationship. It considered all 99 sports listed on the European Commission’s webpage dedicated to sport (European Commission, n.d.) from elite/professional to grassroots levels.

Data collection

A scoping exercise was undertaken to identify existing research published between 2000 and April 2016 that attempted to estimate the incidence and/or prevalence of any form of GBV in sport in EU countries. The study was conducted before the United Kingdom left the EU and so research relating to the UK was included. Relevant scientific and ‘grey’ literature was identified by searching national/international academic databases (i.e. EBSCO, SportDiscus), repositories of Master’s and PhD theses, and a range of relevant online sources such as National Olympic/Paralympic Committee and sport federation websites. Where they existed, systems of registering (forms of) GBV in each EU Member State were also consulted (i.e. child abuse/domestic abuse registration systems from within sport and/or child protection agencies, crime reporting statistics).

In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders and experts within each EU Member State. In total, more than 100 interviews took place with an approximate duration of 45–60 minutes per interview. These served to check and/or complement the information gathered through the scoping exercise. Interviews were conducted in the native language of the relevant country by national researchers. Respondents included policymakers and institutional/governmental officials responsible for sport, child protection and gender equality officers within and outside sport (particularly those working in the area of violence and abuse), experts in GBV in sport such as academics and advocates, officers on Olympic/Paralympic committees and sport confederations/federations/associations, members of LGBTQI + civil society organisations, and feminist/women’s rights associations focussed on sport.

Challenges in understanding prevalence

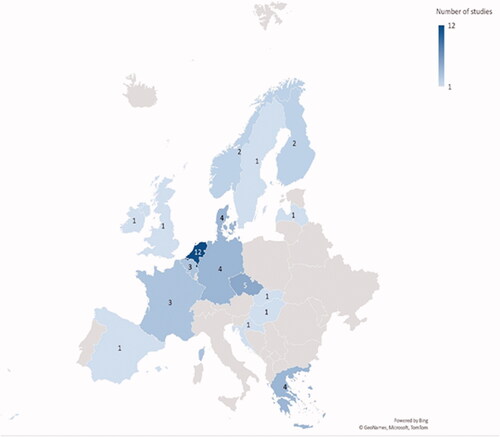

In total, 41 studies were identified that attempted to measure one or more forms of GBV in sport within one or more EU Member States (see Appendix 1). These covered 17 different Member States; their geographical distribution is indicated in . The number of studies identified in totals more than 41 because some studies covered multiple EU Member States and so are recorded twice, once in each country. We discuss these studies below. First, we present some of the challenges we faced when investigating and interpreting the prevalence data.

Figure 1. Overview of available research about GBV in sport in EU Member States at the time of the research. The numbers indicate the number of studies identified per country.

Definitional challenges

Defining GBV is challenging and is influenced by historical, political, cultural, and social factors (Henry, Citation2018; Mergaert et al., Citation2016). Consequently, various definitions of GBV exist. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the definitions of (forms of) GBV used in the 41 studies identified for this research varied considerably. None of the studies used the EC’s definition of GBV. In addition, some failed to acknowledge the gendered aspect of the violence being investigated. For example, some studies considered types of sexual violence but did not define the form(s) of violence being investigated as a type of GBV, failing to acknowledge the behaviour as rooted in inequitable gender relations.

The differing age of sexual consent across EU Member States also caused challenges. Ages of legal consent vary, making comparison of data across countries difficult. In addition, sexual activity that involves children under the legal age of consent is automatically categorised as child sexual abuse, even if the child involved believes they consented (Waites, Citation2005) and, therefore, may have reported in self-administered prevalence studies that they did not experience sexual abuse.

Question formulation also impacted on prevalence rates and rendered cross-country comparisons problematic. Definitions used varied from objective to subjective; some studies used objective, often legal, definitions of violence/abuse and asked respondents to indicate if they had experienced behaviours in these categories regardless of whether or not they considered the behaviour abusive. Others focussed on ‘victims’’ subjective interpretations of their experience. Furthermore, a handful of studies used witnessing forms of GBV as a proxy measure for prevalence instead of or as well as asking respondents if they had experienced (forms of) GBV themselves. This lack of consensus represents a significant limitation for comparisons of existing prevalence rates of GBV in sport.

Methodological challenges

In addition to these challenges, a variety of approaches were used to collect the data we report here. Some studies focussed only on sport contexts, targeting only either current or former athletes as respondents. Others used general population samples and named sport as one of several settings in which GBV occurred. These differing approaches have significant consequences for understandings of the extent of GBV within sport. In studies of the general population, not all respondents will be involved in sport. Consequently, those reporting experiences of GBV in sport will be lower than if the study had focussed only on sport contexts. Equally, when sport settings are aggregated within other settings (such as leisure or youth settings), it is impossible to identify an estimated prevalence rate for GBV that occurs specifically within sport. On the other hand, investigating individuals’ experiences of GBV across different socio-cultural settings and among general population samples has the advantage of resulting in clear comparisons between settings, which is often of interest to policymakers.

Meanwhile, some studies used large and/or representative samples of the general population, while others targeted certain subgroups within sport (such as student-athletes or ‘elite’ athletes) and had relatively small samples. Variations in both the sample size and the composition of the sample require caution when interpreting data and results can rarely be generalised to broader population groups or settings. Studies that ask respondents to report retrospectively on their experiences, as was the case in many of the studies reported on here, are also problematic given that memory bias can enhance and/or impair the recall of past experiences, resulting in false negatives and measurement error (Hardt & Rutter, Citation2004).

A further challenge related to understanding the motive behind the incidents reported. It cannot and should not be assumed that every act of violence reported in research and official reports of GBV is linked to the ‘victim’s’ gender. Some studies identified in this research did not specifically consider the motives for the violence reported or did not disaggregate on the basis of the sex and/or gender expression or identity of ‘victims’. As such, it is not always possible to distinguish between violence that is rooted in gender inequity and that which is not.

One final issue relating to research on the prevalence of GBV in and beyond sport is the sensitivity of the topic. Response rates in several of the studies were low and convenience samples were commonly used. It is also possible that people with experience of GBV are more inclined to participate in studies on this topic than those who do not have such experiences. These factors could cause bias due to possible differences in responders versus non-responders on the research variables (Meterko et al., Citation2015). Indeed, research on sensitive topics often has a higher likelihood of non-disclosure and lower response rates than other forms of research (Radford et al., Citation2011). Consequently, studies of the prevalence of GBV (and other forms of violence) such as those reported here likely underestimate the extent of the problem. In some countries, stakeholders interviewed for the study suggested that the taboo nature of GBV and, in some cases, the outright denial by those in authority that GBV occurs in sport, may explain why there are relatively few studies of the prevalence of (forms of) GBV in sport in EU Member States and why response rates are often low in existing studies. These caveats make comparison between and interpretation of the studies identified challenging. Nevertheless, the work reported below represents an important, albeit tentative, first step towards understanding the prevalence of GBV in EU sport.

Estimates of the prevalence of GBV in EU sport

None of the 41 studies identified for this research used the EC’s definition of GBV and none considered all forms of GBV in sport that encompass the EC’s definition (See Appendix 1). It is therefore not possible to provide an overall estimate of the prevalence of GBV in EU Member States. Despite this, and notwithstanding the caveats noted above, the studies offer a useful insight into the extent of (certain forms of) GBV in sport. The following section discusses the forms of GBV identified along with prevalence rates. The studies are grouped based on the terminology they used.

Sexual harassment

The most frequently studied form of GBV in sport was sexual harassment: Of the 41 studies, 18 attempted to measure (alone or in combination with other forms of GBV) the prevalence of sexual harassment in sport across 10 countries (see Appendix 2). In these studies, the prevalence rate varied between 1% and 64%.

Several studies used current or former student-athletes or students as their sample (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Fasting et al., Citation2011, Citation2014; Martín & Juncà, Citation2014; Vanden Auweele et al., Citation2008), while others used a general sample of athletes. Three studies included a range of sport stakeholders as respondents – athletes, club administrators, referees, and trainers/coaches (Romijn et al., Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2015) – while another study involved women in the general population and included sport as one possible setting where sexual harassment could occur (Mueller, Citation2007). Most studies asked about experiences of sexual harassment across all sports but one focussed on athletes in a single sport – equestrian events (Laukkanen, Citation2015). Most of the studies included only females in their sample (Chroni & Fasting, Citation2009; Fasting et al., Citation2011; Fasting & Knorre, Citation2005; Martín & Juncà, Citation2014; Mueller, Citation2007; Sand et al., Citation2011; Vanden Auweele et al., Citation2008), and one included only men and women who identified as non-heterosexual (Elling et al., Citation2011).

Rather than report overall prevalence rates, some studies disaggregated results by the respondents’ perceptions of the seriousness of the behaviour experienced, further complicating comparisons. For example, Vanden Auweele et al. (Citation2008) reported a prevalence of 13% for ‘very serious’ sexually harassing behaviours among respondents at one university and between 44% and 50% for ‘serious’ behaviours. Meanwhile, students from a second university reported a prevalence of between 2% and 5% for ‘very serious’ and between 20% and 25% for ‘serious’ behaviours. Three studies (Romijn et al., Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2015) gave figures for the number of sport stakeholders who reported witnessing a case of sexual harassment in sport in the past year rather than for personally experiencing sexual harassment. As such, these studies were reporting incidence rates rather than prevalence rates. One study (Sand et al., Citation2011) did not generate any new data on the prevalence of sexual harassment in sport; rather it conducted secondary analyses of the data gathered by Fasting et al. (Citation2011) to identify the relationship between coaching styles and experiences of sexual harassment in sport. It was included in our study because the remit of our study was to identify all research that reported prevalence rates. The study found the more authoritarian the coaching style adopted, the higher the reported rate of sexual harassment.

A common finding across studies that included males and females was that female athletes, whether adults or children, were more likely to report experiencing sexual harassment than males. In addition, studies that included athletes from across the performance spectrum showed that elite athletes are at higher risk of experiencing sexual harassment than athletes at lower performance levels.

Meanwhile, an additional two studies asked respondents if they had witnessed ‘undesirable conduct’ in sport, with the definition of ‘undesirable conduct’ including sexually harassing behaviours as well as other ‘unethical behaviours’, such as physical aggression, smoking, and alcohol consumption. One found 26% of sport stakeholders had witnessed such behaviour (Tiessen-Raaphorst et al., Citation2008), while the other found 17% had witnessed sexist jokes about women (Tiessen-Raaphorst & Breedveld, 2007). Crucially, however, these studies included multiple behaviours under the banner of ‘undesirable conduct’, including some that clearly fall within the EC’s definition of GBV; others, such as physical aggression, that may or may not; and still others, such as smoking, that do not constitute GBV. Consequently, it is impossible to state GBV prevalence rates from these studies with any certainty or say whether gender was an aggravating factor in behaviours that constituted GBV.

Sexual violence

The second most frequently used term in the studies was ‘sexual violence’. Eight studies covering seven countries used this term (see Appendix 3), reporting prevalence rates of between 0.2% and 14%. Definitions of sexual violence used in the studies again varied but included both contact and non-contact behaviours. In some studies, definitions of ‘sexual violence’ overlapped with studies cited above that investigated sexual harassment, making comparison between studies and countries difficult. Five studies investigated forms of violence experienced by a sub-group of the general population, specifically women (Mueller, Citation2007) and children (Fico, Citation2013; Kinderrechtencommissariaat, Citation2011; Stadler et al., Citation2012; TNS Latvia, Citation2015). These also investigated other forms of violence beyond sexual violence and did not explicitly refer to GBV or acknowledge sexual or other forms of violence as rooted in gender inequity. Additionally, since these studies involved general population samples, very few respondents had experience of participating in sport, compromising the resulting prevalence rates.

In other studies (i.e. Fico, Citation2013; Mueller, Citation2007), sport was grouped together with other settings, reducing the extent they can be used to inform us about sexual violence rates in sport. For example, in Fico (Citation2013) sports staff were included within a general category of ‘other adult known to victim’ alongside neighbours, sales staff, and religious leaders. Similarly, Mueller (Citation2007) grouped sports coaches together with staff from nursing, childcare, youth centres, or leisure settings. Consequently, the prevalence rates reported for sport in these studies need to be treated with caution as sport was only one of several settings included and very few respondents reported their abuse occurred in these settings (i.e. only 3 out of 1,560 respondents in Fico, Citation2013).

There were also significant differences across studies in terms of the types of violence explored. While some studies that used the term ‘sexual violence’ investigated only sexual violence, most investigated various forms of violence, including but not limited to sexual forms (i.e. Fico, Citation2013; Mueller, Citation2007; Vertommen et al., Citation2016). To further complicate matters, some studies separated results into contact or non-contact forms of sexual violence – for example, being touched inappropriately (contact) versus receiving a sexually explicit text message (non-contact) (Stadler et al., Citation2012; TNS Latvia, Citation2015) – while others did not differentiate in this way.

Several studies asked respondents retrospectively about their experiences as children (Stadler et al., Citation2012; Vertommen et al., Citation2016) and defined ‘child’ using the age of sexual consent in the country where the study was conducted. Others asked only about experiences as adults (Mueller, Citation2007), and others questioned current athletes, regardless of age, so included children and adults in their sample and did not differentiate between these in their results (Décamps et al., Citation2008). Only one study disaggregated results by sexual orientation, ethnicity, and disability (Vertommen et al., Citation2016).

Three studies used samples of individuals screened in advance as playing/having played sport (Décamps et al., Citation2008; Johansson, Citation2012; Vertommen et al., Citation2016). Of these, two investigated (forms of) GBV violence in a single country (France and Sweden, respectively); only Vertommen et al. (Citation2016) provided a comparison of experiences of sexual violence across two countries, the Dutch-speaking areas of the Netherlands and Belgium (Flanders). In studies that used samples from sport populations, the reported prevalence rate for sexual violence was between 5% and 17%. On the other hand, studies that questioned respondents about their experiences of sexual violence in general, rather than specifically in sport, found lower rates, between 0.2% and 3%. Most studies found women reported experiencing sexual violence more than men. Finally, one study provided separate statistics for respondents’ personal experiences of sexual violence and for whether they had witnessed (forms of) sexual violence (Stadler et al., Citation2012). The study, which used a general population sample and asked about experiences in a range of settings including sports clubs, found that 3.2% of males and 0.6% of females reported experiencing sexual violence that involved physical contact and 4.2% of females reported experiencing non-contact sexual violence (e.g. being shown pornography) in sports clubs. No males reported experiencing non-contact sexual violence in this setting. Meanwhile, 0.9% of males and 1.4% of females had witnessed acts of ‘exhibitionism’ (‘flashing’), one form of sexual violence, in sports clubs (Stadler et al., Citation2012).

Sexual abuse

The term ‘sexual abuse’ was used in four studies (Helweg-Larsen, Citation2003; Nielsen, Citation2001; Stoeckel, Citation2010; Vanden Auweele et al., Citation2008). Most commonly, this term was used when investigating (forms of) GBV perpetrated against children in sport. Across these studies, the prevalence rate varied between 0.3% and 14%.

Of these studies, three were conducted in Denmark with male and female respondents (Helweg-Larsen, Citation2003; Nielsen, Citation2001; Stoeckel, Citation2010), while one was conducted in the Flemish region of Belgium with only female respondents (Vanden Auweele et al., Citation2008). One used a general population sample (Helweg-Larsen, Citation2003) while the others used samples from within sport. Notably, the general population study (Helweg-Larsen, Citation2003) reported a much lower prevalence rate than the other three studies, highlighting our earlier concern regarding the use of general population samples to investigate prevalence rates within sport. This same study focussed solely on sexual abuse; the three others also addressed non-sexual abuse. Again, what constituted sexual abuse in each study was defined differently. Stoeckel (Citation2010) and Vanden Auweele et al. (Citation2008) asked about experiences of a range of sexual behaviours. Vanden Auweele et al. (Citation2008) included behaviours that would perhaps more accurately be defined as sexual harassment (i.e. making sexual comments) or sexual exploitation (i.e. being sexually propositioned in exchange for rewards), while Stoeckel (Citation2010) included consensual sexual relationships between a coach and an adult athlete as well as illegal sexual activity between an adult coach and a child athlete, though results were disaggregated by the age of the respondent making it possible to identify objectively defined child sexual abuse. Meanwhile, some studies did not exclusively investigate sexually abusive behaviours. For example, Vanden Auweele et al. (Citation2008) asked athletes if they had ever experienced a coach telling lewd jokes, inviting them to attend a non-sporting social event such as dinner, or giving them a back massage, while Nielsen (Citation2001) asked about a coach making fun of an athlete’s performance. Importantly, while such behaviours may, depending on the context, be unethical, they do not necessarily constitute sexual abuse. It is also impossible to know if the behaviours experienced were directed against the athletes because of their gender, making it impossible to determine if all the prevalence rates reported should be classified as (forms of) GBV.

Importantly, in one of the studies (Nielsen, Citation2004) 8% of children in sport (defined in the study as under age 18 as per the Danish age for sexual consent) reported engaging in an intimate relationship with a coach before they reached 18. However, in a separate question, only 0.2% of respondents reported they had experienced sexual abuse. In other words, there were clear differences between child respondents’ experiences of legally defined sexual abuse and their perceptions of whether particular behaviours constituted sexual abuse; many did not construct their relationships as abusive, despite a child not being able to legally consent to sexual contact.

Sexual harm and sexual assault

Two studies, one in the UK and one in France, used the term ‘sexual harm’ (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Décamps et al., Citation2008). Both focussed only on the experiences of children in sport. Use of the term ‘harm’ in this context is likely because subjective descriptions, such as whether a behaviour caused or could cause harm to a child, often feature within national definitions of child abuse alongside more objective examples of acts that constitute child abuse (see World Health Organization, Citation2016). These studies reported prevalence rates for sexual harm between 2% and 57% – a difference that can be attributed to the different definitions used and the range of behaviours asked about. In the UK study, Alexander et al. (Citation2011) defined sexual harm as being forced to kiss someone, having someone expose their genitals to them, being touched sexually against their will, someone trying to have sex with them against their will, or being forced to have penetrative sex. They reported a prevalence rate of 3% for these forms of sexual harm. Meanwhile, Décamps et al. (Citation2008) defined sexual harm as four separate behaviours: (1) sexual harassment, (2) exhibitionism/ voyeurism, (3) sexual attacks, and (4) sexual assault/aggression. They questioned adult and child athletes about their experiences as children in sport and found that 13% of female respondents and 10% of male respondents reported experiencing some form of sexual harm.

The term ‘sexual assault’ was used in two studies, both from France (Choquet, Citation2001; Décamps et al., Citation2008). The prevalence for sexual assault was between 2% and 7%. As with other studies reported here, there were significant differences between the definitions and samples used. Choquet’s (Citation2001) study used a small sample of 117 sports students at one university. Meanwhile, in Décamps et al. (Citation2008) study, the questionnaire was disseminated through national and some regional sports institutes, university faculties of sport, and some high schools. As a result, some of the largest national sport federations in France were excluded from the study (cycling, for example) as were many professional athletes, and only eight out of the then-26 French regions were included. In both these studies, therefore, the samples were not representative so the results should be treated with caution.

Emotional/ psychological violenceFootnote1 and physical violence

GBV is not only sexual in nature and while studies reporting sexual forms of GBV dominated, some research addressed other forms. Four studies from four different countries, all of which also asked about sexual violence, investigated the prevalence of emotional/psychological violence in sport (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Bosnar et al., Citation2007; TNS Latvia, Citation2015; Vertommen et al., Citation2016). The reported prevalence rate across these was between 2% and 80%. Meanwhile, five studies covering six countries reported on forms of physical violence (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Bosnar et al., Citation2007; Romijn et al., Citation2015; TNS Latvia, Citation2015; Vertommen et al., Citation2016). These reported prevalence rates of between 1% and 50%, with differences again attributable to the definitions used.

Importantly, while GBV can manifest through emotional/psychological and physical violence, the studies cited above did not investigate whether the respondents’ believed experiences of these forms of violence were related to their gender or gender identity/expression. However, it is likely these studies remain relevant to understanding GBV rates in sport since in at least two cases (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Vertommen et al., Citation2016) results indicate that athletes of one sex were disproportionately affected, meaning they fall within the EC’s definition of GBV (European Commission, Citation2014). Admittedly, it is impossible to know how much of the violence reported in these studies was directed against respondents because of their gender, gender identity and/or gender expression and it is possible that the studies may over-estimate the extent of emotional/psychological and physical violence in sport that results from inequitable gender relations. However, any over-estimation would be compensated for by the fact that it has long been recognised that underestimating is a greater risk than overestimating when it comes to sensitive topics such as the prevalence of violence (Maughan & Rutter, Citation1997). In addition, research on emotional/psychological and physical violence in sport is likely to further underestimate the extent of the problem because many such behaviours are normalised as part of sports practice (Lang, Citation2021a; Solstad & Strandbu, Citation2019).

Homophobic violence

Research that investigates the extent of homophobic violence in sport remains rare, even within EU countries where studies on other forms of GBV in sport exist. In Germany, for example, where there is research on the magnitude of certain forms of GBV in sport and where sport policy and legislative frameworks exist nationally for preventing and managing forms of GBV (Rulofs et al., Citation2019), no studies were identified that attempted to measure the magnitude of homophobic violence in sport. This is a concern given that athletes who identify as LGBTQI + are known to be at higher risk of experiencing all forms of violence in sport than non-LGBTQI + athletes (Vertommen et al., Citation2016).

Only four of the 41 studies, covering only three countries, included any information on homophobic violence in sport (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Kokkonen, Citation2012; Romijn et al., Citation2013, Citation2015). One included in the sample only athletes belonging to gender or sexual minorities (Kokkonen, Citation2012), while another compared prevalence rates for forms of violence experienced by heterosexual athletes and athletes who identified as gay or lesbian (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015). Across studies, prevalence rates for homophobic violence were between 4% and 89% depending on the type of behaviour experienced (i.e. bullying, verbal abuse, physical violence).

Notable developments

Despite the significant challenges and limitations reported above, one noteworthy positive development is evident in more recent studies: There is a trend towards using more rigorous methodologies for measuring the extent of (forms of) GBV in sport. More recently conducted research tended to adopt more robust methodological designs – using representative samples and more comparable variables, for example (i.e. Vertommen et al., Citation2016). The most recent research was also more likely to include male respondents rather than focus only on women and girls in recognition that violence against men can also be gendered (Carpenter, Citation2006; i.e. Vertommen et al., Citation2016).

Examples of cross-cultural comparative work are also beginning to appear. Fasting et al. (2011) adopted the same methodology to collect data on sexual harassment experienced by student-athletes in three European countries (Norway, the Czech Republic, and Greece) whereby the key concepts and example behaviours in the study were translated into the languages of the target populations. Vertommen et al. (Citation2016) adopted a similar approach in their study in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Conclusion and recommendations

While the data clearly indicated that GBV in sport exists, methodological and definitional limitations in research represent major stumbling blocks to a robust understanding of the extent of GBV in sport across and within EU Member States. There is an absence of reliable prevalence data on (all forms of) GBV in sport. While there is some limited evidence of scientifically sound prevalence estimates for (certain forms of) GBV in sport in a handful of Member States, no data on the magnitude of the problem exists in most countries; data on (forms of) GBV in sport was only identified in 17 countries, meaning no data was available in 11 countries between 2000 and 2016 and no studies on the prevalence of GBV in sport in the EU have since been published.

Nevertheless, the figures reported here indicate that, as Palermo et al. (Citation2014) note about GBV in wider society, GBV is widespread in sport. Representative samples for all sport disciplines were not available from the 41 studies identified. However, to date there is no evidence to indicate that there are any significant differences in prevalence rates of (forms of) GBV between different sport disciplines, though more work is needed on this. Most studies that provide sex-disaggregated figures report a higher prevalence of (most forms of) GBV in sport among women and girls compared with men and boys, especially for sexual violence. However, some empirical work that has focussed on a range of forms of GBV suggests that rates of physical (forms of) violence may be higher among males compared with females (Vertommen et al., Citation2016). This highlights the importance of including men and boys in future studies.

Furthermore, only a handful of studies disaggregate data by sexual orientation and/or sexual identity, with most conceptualising gender in a simplistic, binary way and ignoring trans, queer, and non-binary individuals completely. Similarly, few studies address other markers of gendered difference, such as disability and ethnicity. As such, existing data rarely engage with gender inequity from an intersectional perspective. Studies that do disaggregate data indicate higher levels of sexual forms of GBV perpetrated against LGBTQI+, disabled, and ethnic minority athletes (Alexander et al., Citation2011; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Vertommen et al., Citation2016). Therefore, specific attention should be paid within policy development and evaluation on GBV in sport to (forms of) violence committed against specific groups.

Future research must also avoid adopting a single-issue approach and instead recognise the value of intersectionality in understanding and preventing GBV in sport. Specifically, more research is needed to understand to what extent and how gender intersects with other forms of oppression. Indeed, research from outside sport suggests racism, homophobia, transphobia, and ableism can be contributing factors to violence. This impacts on individuals’ and institutional responses to suspicions or disclosures of violence (Fitzgerald, Citation2021; Iganski, Citation2016; Krieger, Citation2008; Mueller et al., Citation2019; Rodger et al., Citation2020; Thorneycroft & Asquith, Citation2021). Research on GBV in sport has yet to acknowledge or investigate these issues so this must be a priority for future researchers and sport policymakers.

Strong empirical evidence on the extent of GBV in sport is vital. Despite the almost total absence of robust prevalence data, several countries have developed policies and prevention programmes to combat GBV in sport (see Mergaert et al., Citation2016). However, without the existence of baseline prevalence estimates within sport in every EU Member State, it is impossible to measure the effectiveness (or otherwise) of such initiatives or to know which forms of GBV require the most urgent response.

Some countries are still reluctant to acknowledge that GBV occurs in sport (see Lang & Hartill, Citation2015) and in some countries data on (any form of) violence against adults and children in wider society is lacking so it is unsurprising that there is no data on GBV in sport either. It would be short-sighted to assume that GBV does not occur in sport where there is, as yet, no prevalence data. Equally important, however, is the recognition that, as is the case with GBV in other settings (such as the family, workplaces), where attempts have been made to measure the prevalence of (forms of) GBV in sport, these figures are almost certainly a significant underestimate of the extent of the problem as many cases are never reported or disclosed (Andersson et al., Citation2009; Hartill & Lang, Citation2018). As mentioned earlier, identifying the prevalence of GBV in sport can only positively impact policymaking in this area.

Since the data reported here were compiled and reported to the EACEA in late 2016, there has been no new research published that measures (forms of) GBV in sport across EU Member States. To address the current lack of robust prevalence data, the European Commission, with the support of Member States, should commission regular research that uses the same definitions and adopts a common methodological approach to facilitate comparisons over time. In early 2021, the EC’s newly established ‘High Level Group on Gender Equality in Sport’ convened for the first time (Fonda, Citation2021). This group offers one pathway to tackling gender inequity in EU sport and we suggest that proposing and supporting ways of addressing the gap in knowledge regarding the prevalence of GBV in sport across Member States as one point of action for the group.

We also suggest that questions aimed at measuring the extent of GBV in different settings, including in sport, be included in national and European studies that already exist, such as in general household surveys, in the European survey on GBV that is coordinated by the Fundamental Rights Agency (on the condition that this survey is broadened to include men and not only women affected by GBV in and beyond sport), or in the European Commission Eurobarometer surveys.

Finally, while the research reported here focussed on what is known about the prevalence of (forms of) GBV in sport against athletes, we also acknowledge that very little is known about GBV perpetrated against other members of the sports community, such as coaches and sports officials. Concerted efforts are needed to address this gap.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the European Commission’s Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency for funding the study on which this paper is based. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Maria Sola García for her involvement as a member of the core team for the study. In addition, we are grateful for the work done by the national researchers in each EU country (details of these can be found on page 4 of the final report here: https://ec.europa.eu/sport/sites/sport/files/gender-based-violence-sport-study-2016_en.pdf), and for the support provided during the study from advisory board members Celia Brackenridge, ‘Ani’ Stiliani Chroni, Kari Fasting, Bettina Rulofs, and Jan Toftegaard Støckel. Dr. Melanie Lang would also like to thank Edge Hill University’s Research Office for funding her attendance at a conference where an earlier version of this paper was presented.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These terms are used interchangeably in the literature.

References

- Alexander, K., Stafford, A., & Lewis, R. (2011). The experiences of children participating in organized sport in the UK. The University of Edinburgh/NSPCC.

- Andersson, N., Cockcroft, A., Ansari, N., Omer, K., Chaudhry, U. U., Khan, A., & Pearson, L. (2009). Collecting reliable information about violence against women safely in household interviews: Experience from a large-scale national survey in South Asia. Violence against Women, 15(4), 482–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208331063

- Audit Commission. (2016). Report Audit Commission Sexual Harassment (ISR) 2014. (Internal report for the executive board of NOC*NSF). Audit Commission.

- Baiocco, R., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., & Lucidi, F. (2018). Sports as a risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a sample of gay and heterosexual men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 22(4), 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2018.1489325

- Bosnar, K., Greblo, Z., Prot, F., & Sporiš, G. (2007). Iskustvo sportaša adolescentne dobi s nasilnim ponašanjem trenera i drugih sportaša [Experiences of violence in adolescent sport activities committed by coaches and by fellow athletes]. In U. V. Kolesarić (Ed.), Psihologija i nasilje u suvremenom društvu [Psychology and violence in contemporary society] (pp. 159–168). Tiskara i knjigovežnica Filozofskog fakulteta u Osijeku.

- Brackenridge, C. H. (1994). Fair play or fair game? Child sexual abuse in sport organizations. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 29(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269029402900304

- Brackenridge, C. H. (2001). Spoilsports: Understanding and preventing sexual exploitation in sport. Routledge.

- Carpenter, R. C. (2006). Recognizing gender-based violence against civilian men and boys in conflict situations. Security Dialogue, 37(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010606064139

- Case, R. W., & Boucher, R. L. (1981). Spectator violence in sport: A selected review. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 5(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372358100500201

- Choquet, M. (2001). Jeunes et pratique sportive. L'activité sportive à l'adolescence. Les troubles et conduites associées [Youth and sports. Sport activities of teenagers. A study of risks and related behaviours]. Ministère de la Jeunesse et des Sports-INJEP.

- Chroni, S., & Fasting, K. (2009). Prevalence of male sexual harassment among female sport participants in Greece. Inquiries in Physical Education and Sport, 7(3), 288–296.

- Décamps, G., Afflelou, S., & Jolly, A. (2008). Etude des violences sexuelles dans le sport en France: Contextes de survenance et incidences psychologique [Study on gender-based violence in sport: Context of occurrence and psychological impact]. Ministère de la Santé, des Sports, de la Jeunesse et de la Vie Associative.

- Denison, E., & Kitchen, A. (2015). Out on the fields: Ireland Summary Report. Repucon. Retrieved from http://www.outonthefields.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Summary-of-Irish-Results-Out-on-the-Fields.pdf

- Elling, A., Smits, F., Hover, P., & van Kalmthout, J. (2011). Seksuele diversiteit in de sport: sportdeelname en acceptatie [Sexual diversity in sport: Sport participation and acceptance]. Mulier Institute.

- Elling, A., & van den Dool, R. (2009). Homotolerantie in de sport [Tolerance of homosexuality in sport]. Mulier Institute.

- European Commission. (2014). Gender Equality in Sport. Proposal for Strategic Actions 2014–2020. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/sport/events/2013/documents/20131203-gender/final-proposal-1802_en.pdf

- European Commission (n.d.). European and international federations. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/sport/resources/networks_partners/sport_federations_en.htm

- Fasting, K., Chroni, S., & Knorre, N. (2014). The experiences of sexual harassment in sport and education among European female sports science students. Sport, Education and Society, 19(2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.660477

- Fasting, K., & Knorre, N. (2005). Women in sport in the Czech Republic. Norwegian School of Sport Sciences/ Czech Olympic Committee.

- Fasting, K., Chroni, S., Hervik, S. E., & Knorre, N. (2011). Sexual harassment in sport toward females in three European countries. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210376295

- Fico, M. (2013). Prevalencia násilia páchaného na deťoch v Slovenskej republike [Prevalence of violence against children in the Slovak Republic]. Inštitút pre výskum práce a rodiny.

- Fitzgerald, H. (2021). The welfare of disabled people in sport. In M. Lang (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of athlete welfare (pp. 183–195). Routledge.

- Fonda, P. (2021). The first meeting of the High Level Group on Gender Equality in Sport. Retrieved from: https://www.engso.eu/post/the-first-meeting-of-the-high-level-group-on-gender-equality-in-sport

- Hall, M. A. (1985). How should we theorize sport in a capitalist patriarchy? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 20(1–2), 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269028502000110

- Hardt, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 45(2), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

- Hartill, M., & Lang, M. (2018). Official reports of child protection and safeguarding concerns in sport and leisure settings: An analysis of English local authority data. Leisure Studies, 37(5), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1497076

- Helweg-Larsen, K. (2003). Seksuelle kraenkelser af børn og unge inden for idraet: Den aktuelle forekomst og forebyggelse [Sexual violation of children and young people in sport: Current incidence and prevention]. Ministry of Culture.

- Henry, C. (2018). Exposure to domestic violence as abuse and neglect: Constructions of child maltreatment in daily practice. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.018

- Iganski, P. (2016). Understanding the needs of persons who experience homophobic or transphobic violence or harassment the impact of hate crime. Warsaw, Kampania Przeciw Homofobi. Retrieved from https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/83775/1/Understanding_the_Needs_of_Persons_Who_Experience_Homophobic_or_Transphobic_Violence_or_Harassment.pdf

- Jeckell, A. S., Copenhaver, E. A., & Diamond, A. B. (2018). The spectrum of hazing and peer sexual abuse in sports: A current perspective. Sports Health, 10(6), 558–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738118797322

- Johansson, S. (2012). Kunskapsöversikt: Sexuella övergrepp – i relationen mellan tränare och idrottsaktiv [Sexual abuse in the relations between coach and athlete]. The Swedish Sports Confederation.

- Kerr, G., Willson, E., & Stirling, A. (2020). It was the worst time of my life: The effects of emotionally abusive coaching on female Canadian national team athletes. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 28(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2019-0054

- Kinderrechtencommissariaat. (2011). Geweld, gemeld en geteld. Aanbevelingen in de aanpak van geweld tegen kinderen en jongeren [Violence reported and counted: Recommendations in addressing violence against children and youth]. Kinderrechtencommissariaat.

- Kokkonen, M. (2012). Seksuaali- ja sukupuolivähemmistöjen syrjintä urheilun ja liikunnan parissa [The discrimination of sexual and gender minorities in sports and exercise]. National Sports Council/ Ministry of Education and Culture.

- Krieger, N. (2008). Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: An ecosocial perspective. American Journal of Public Health, 98(9 Suppl), S20–S25. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s20

- Lang, M. (2010a). Intensive training in youth sport: A new abuse of power? In M. Lang, & K. P. Vanhoutte, (eds.) Bullying and the abuse of power: From the Playground to International Relations (pp. 57–64). Inter-Disciplinary Press.

- Lang, M. (2010b). Surveillance and conformity in competitive youth swimming. Sport, Education and Society, 15(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320903461152

- Lang, M. (2021a). Developments in international policy on athlete welfare. In M. Lang (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Athlete Welfare (pp. 15–23). Routledge.

- Lang, M. (2021b). The Routledge Handbook of Athlete Welfare. Routledge.

- Lang, M., & Hartill, M. (2015). Safeguarding, child protection and abuse in sport: International perspectives in research, policy and practice. Routledge.

- Lang, M., Mergaert, L., Arnaut, C., & Vertommen, T. (2018). Gender-based violence in EU sport policy: Overview and recommendations. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 2(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868018X15155986979910

- Laukkanen, L. (2015). Ratsastuksen Reilu Peli – Lajin eettiset periaatteet, nykytila ja tavoitteet [Fair play in horse riding – ethical principles, current state and goals]. (Bachelor’s thesis). Häme University of Applied Sciences, Mustiala, Finland.

- Lenskyj, H. (1992). Unsafe at home base: Women’s experience of sexual harassment in university sport and physical education. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 1(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.1.1.19

- Martín, M., & Juncà, A. (2014). Departament d’Activitat Física, Grup de Recerca Esport i Activitat Física (GREAF) [Sexual harassment in sport: The case of student-athletes reading for a degree in physical activity and sport science in Catalonia]. University of Vic.

- Maughan, B., & Rutter, M. (1997). Retrospective reporting of childhood adversity: Issues in assessing long-term recall. Journal of Personality Disorders, 11(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.19

- McPherson, L., Long, M., Nicholson, M., Cameron, N., Atkins, P., & Morris, M. E. (2017). Secrecy surrounding the physical abuse of child athletes in Australia. Australian Social Work, 70(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1142589

- Mergaert, L., Arnaut, C., Vertommen, T., & Lang, M. (2016). Study on gender-based violence in sport in EU Member State countries: Results of a Study Commissioned by the European Commission Education, Audio-visual and Culture Executive Agency. European Commission.

- Meterko, M., Restuccia, J. D., Stolzmann, K., Mohr, D., Brennan, C., Glasgow, J., & Kaboli, P. (2015). Response rates, non-response bias, and data quality: Results from a national survey of senior healthcare leaders. Public Opinion Quarterly, 79(1), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu052

- Mueller, C. O., Forber-Pratt, A. J., & Sriken, J. (2019). Disability: Missing from the conversation of violence. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12339

- Mueller, U. (2007). Sexuelle gewalt und übergriffe: Ein thema für den sport? [Trans. Sexual violence and abuse: A topic for sport?]. In B. Rulofs (Ed.), Schweigen schützt die Falschen: Sexualisierte gewalt im sport – Situationsanalyse und Handlungsmöglichkeiten [Trans. Silence protects the wrong people: Sexualized violence in sport – a situation analysis and opportunities for action] (pp. 9–18). Ministry of the Interior of North Rhine-Westphalia.

- Nery, M., Neto, C., Rosado, A., & Smith, P. K. (2020). Bullying in youth sports training: New perspectives and practical strategies. Routledge.

- Nielsen, J. T. (2001). The forbidden zone: Sexual relations and misconduct in the relationship between coaches and athletes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 36(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269001036002003

- Nielsen, J. T. (2004). Idraettens Illusoriske Intimitet [The illusion of sport intimacy] (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Copenhagen.

- Nurse, A. M. (2018). Coaches and child sexual abuse prevention training: Impact on knowledge, confidence and behaviour. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.040

- Oliver, J., & Lloyd, R. (2015). Physical training as a potential form of abuse. In M. Lang, & M. Hartill (Eds.), Safeguarding, child protection and abuse in sport: International perspectives in research, policy and practice (pp. 163–171). Routledge.

- Palermo, T., Bleck, J., & Peterman, A. (2014). Tip of the iceberg: Reporting and gender-based violence in developing countries. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179(5), 602–612. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt295

- Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007

- Radford, L., Corral, S., Bradley, C., Fischer, H., Bassett, C., Howat, N., & Collishaw, S. (2011). Child abuse and neglect in the UK today. NSPCC.

- Rodger, H., Hurcombe, R., Redmond, T., George, R., Butt, J., Bignall, T., Phillips, M., Rhoden, B., & Richardson, C. (2020). “People don’t talk about it”: Child sexual abuse in ethnic minority communities. Report for the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. Retrieved from https://www.iicsa.org.uk/reports-recommendations/publications/research/child-sexual-abuse-ethnic-minority-communities

- Romijn, D., Van Kalmthout, J., & Breedveld, K. (2014). VSK-monitor 2014. Voortgangsrapportage Actieplan ‘Naar een veiliger sportklimaat. Mulier Instituut.

- Romijn, D., van Kalmthout, J., & Breedveld, K. (2015). VSK-monitor 2014 Voortgangsrapportage Actieplan ‘Naar een veiliger sportklimaat’ [Safe sport climate monitor 2014: Progress report action plan ‘Towards a safe and respectful sport environment’]. Mulier Instituut.

- Romijn, D., van Kalmthout, J., Breedveld, K., & Lucassen, J. (2013). VSK-monitor 2013. Voortgangsrapportage Actieplan ‘Naar een veiliger sportklimaat. Mulier Instituut.

- Rulofs, B., Feiler, S., Rossi, L., Hartmann-Tews, I., & Breuer, C. (2019). Child protection in voluntary sports clubs in Germany: Factors fostering engagement in the prevention of sexual violence. Children & Society, 33(3), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12322

- Sand, T. S., Fasting, K., Chroni, S., & Knorre, N. (2011). Coaching behaviour: Any consequences for the prevalence of sexual harassment? International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 6(2), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.2.229

- Solstad, G. M., Strandbu, Å. (2019). Faster, higher, stronger … safer? Safety concerns for young athletes in Zambia. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(6), 738–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217742926

- Stadler, L., Bieneck, S., & Pfeiffer, C. (2012). Representative survey sexual abuse 2011. Lower Saxony Criminological Research Institute.

- Stoeckel, J. T. (2010). Athlete perceptions and experiences of sexual abuse in intimate coach-athlete relationships. In C. Brackenridge & D. Rhind (Eds.), Elite child athlete welfare: International perspectives (pp. 93–100). Brunel University Press.

- Thorneycroft, R., & Asquith, N. L. (2021). Unexceptional violence in exceptional times: Disablist and ableist violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 10(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1743

- Tiessen-Raaphorst, A., & Breedveld, K. (2007). Een gele kaart voor de sport. Een quick scan naar wenselijke en onwenselijke praktijken in en rondom de breedtesport [A yellow card for sport. A quick scan of desirable and undesirable practices in and around the world of popular sport]. Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau.

- Tiessen-Raaphorst, A., Lucassen, J., Dool, van den R. & Kalmthout, J. van. (2008). Weinig over de schreef: Een onderzoek naar onwenselijk gedrag in de breedtesport [Little crossed the line: A study of unwanted behaviour in sport for all]. Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau.

- TNS Latvia. (2015). Tiesībsarga pētījums par vardarbības izplatību pret bērniem Latvijā [Ombudsman’s study on prevalence of violence against children in Latvia]. TNS Latvia.

- Vanden Auweele, Y., Opdenacker, J., Vertommen, T., Boen, F., Van Niekerk, L., De Martelaer, K., & De Cuyper, B. (2008). Unwanted sexual experiences in sport: Perceptions and reported prevalence among Flemish female student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(4), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671879

- Vertommen, T., Schipper-van Veldhoven, N., Wouters, K., Kampen, J. K., Brackenridge, C. H., Rhind, D. J. A., Neels, K., & van den Eede, F. (2016). Interpersonal violence against children in sport in the Netherlands and Belgium. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.006

- Waites, M. (2005). The age of consent: Young people, sexuality and citizenship. Macmillan.

- White, A., & Brackenridge, C. H. (1985). Who rules sport? Gender divisions in the power structure of British sports organizations from 1960. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 20(1–2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269028502000109

- Williams, J., Dunning, E., & Murphy, P. (1984). Hooligans abroad: The behaviour and control of English fans in continental Europe. Routledge.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Child abuse and neglect by parents and other caregivers. WHO. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap3.pdf

- Yabe, Y., Hagiwara, Y., Sekiguchi, T., Momma, H., Tsuchiya, M., Kanazawa, K., Koide, M., Itaya, N., Yoshida, S., Sogi, Y., Yano, T., Onoki, T., Itoi, E., & Nagatomi, R. (2019). Parents’ own experience of verbal abuse is associated with their acceptance of abuse towards children from youth sports coaches. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 249(4), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.249.249

- Zehntner, C. (2020). Consent and complicity: The athletes’ role in the normalization of damaging coaching practices. In M. Lang (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of athlete welfare (pp. 314–323). Routledge.