ABSTRACT

Vulvodynia is common and has an immense impact on affected women and their partners. Psychological factors have been found to contribute to pain maintenance and exacerbation, and treatments addressing psychological factors have yielded positive results. This study employed a replicated single-case experimental design to examine a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) group treatment with partner involvement in vulvodynia. Repeated measures of pain intensity related to pain-inflicting behaviors were collected weekly throughout baseline and treatment phases. Associated outcomes were measured pre-, post- and at two follow-up assessments. Participants were 18–45-year-old women, in a stable sexual relationship with a man, experiencing vulvodynia. Five women completed the treatment consisting of 10 group sessions and 3 couple sessions. Data were analyzed through visual inspection and supplementary nonparametric calculations. The study showed promising results of the CBT treatment in alleviating pain intensity in connection to specific pain-inflicting behavior since three out of five participants showed improvements. For the participants who improved, sexual function, pain catastrophizing, avoidance, and endurance behavior changed during treatment and were maintained at follow-ups. These results warrant further study of the CBT treatment, in larger, and controlled formats.

Introduction

Vulvodynia is a chronic idiopathic vulvovaginal pain condition (Bornstein et al., Citation2016) with a lifetime prevalence of around 16% (Harlow & Stewart, Citation2003). Population-based prevalence rates are around 7–8% in premenopausal women (Harlow et al., Citation2014; Reed et al., Citation2012) but may be up to 13% in younger women (Danielsson et al., Citation2003). Provoked pain induced by touch, pressure, or vaginal penetration in the vulvar vestibule, also called provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), is the most common form of vulvodynia, and cause of dyspareunia in women (Bornstein et al., Citation2016), with sexual activities being seriously affected. PVD has an immense impact on women and their partners’ sexual function and satisfaction, general psychological and relational well-being, as well as their overall quality of life (for a review, see Bergeron et al., Citation2015).

The last decade of research suggests that psychological factors, such as fear of pain, pain catastrophizing, and avoidance behavior may contribute to the maintenance and exacerbation of PVD (Desrochers et al., Citation2008, Citation2009). These findings are in line with the fear-avoidance model of pain (Thomtén & Linton, Citation2013; Vlaeyen & Linton, Citation2000) where a pain experience may be interpreted as threatening (pain catastrophizing), triggering fear of pain and avoidance behaviors, possibly leading to hypervigilance, muscular tension, disability (sexual dysfunction) and disuse (avoidance of sexual activities in general) (Engman et al., Citation2018; Flink et al., Citation2017; Landry & Bergeron, Citation2011; Ter Kuile et al., Citation2010; Thomtén & Linton, Citation2013). Paradoxically, 50–68% of women with PVD have been found to nevertheless dismiss the pain signals and endure painful sexual activities (Brauer et al., Citation2014; Elmerstig et al., Citation2013). This indicates that endurance—which may be framed as covert avoidance behavior, to avoid emotional consequences such as relational or identity conflicts (Engman et al., Citation2018; Flink et al., Citation2017)—is common, despite it being detrimental for problem development, possibly increasing pain sensitization over time (Van Lankveld et al., Citation2010).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for PVD aims at lessening pain, rebuilding sexual function, and improving sexual aspects by targeting associated cognitions, emotions, behaviors, and couple interactions. CBT treatments for PVD have been delivered in individual, couple, and group formats and have been found to be effective for reducing pain and enhancing psychosexual outcomes (Bergeron et al., Citation2015, Citation2021; Brotto et al., Citation2020; Goldstein et al., Citation2016; Pukall et al., Citation2016; Rosen et al., Citation2019), yet randomized controlled trials are sparse (Bohm-Starke et al., Citation2022). Studies comparing different formats of delivery of CBT for PVD are additionally lacking. The group format is the most evaluated format to date, with benefits such as cost-effectiveness, support from others with similar experiences, and normalization. Moreover, given the interpersonal sexual context in which PVD is most often triggered, relational factors are important to address. It has thereby been recommended to include partners in CBT treatments for vulvodynia (Bergeron et al., Citation2018).

With this background, comprehensive CBT treatments targeting associated psychological, sexual, and relational factors in addition to the pain itself are promising treatment alternatives. The current study utilizes a group CBT treatment based on a previously tested protocol (Ter Kuile & Weijenborg, Citation2006). The treatment protocol was adjusted by adding three couple sessions, to enhance the relational focus and emphasize the support and involvement of the partner. The protocol aims at reducing fear of pain through systematic exposure exercises targeting both covert (endurance) and overt avoidance behavior, enhancing sexual function by broadening of the sexual repertoire, addressing muscular tension by general and specific relaxation exercises, targeting pain catastrophizing via cognitive strategies, reducing generalized avoidance behavior through exposure exercises, and counteract endurance behavior by implementing a strict pain prohibition.

As the original protocol has been enhanced and adjusted, this study aims at evaluating the effect of a CBT group treatment with partner involvement for PVD on the woman’s pain experience, captured by three complementary measures of pain associated with different pain-inflicting behaviors, and associated outcomes, by employing a replicated single-case experimental design as an initial proof of concept.

Methods

Design

The current study was used as initial testing in preparations of a registered randomized waitlist controlled multicenter trial of efficacy (National Library of Medicine, NCT03427255), included in the ethical application which was approved by the regional board of ethics in Uppsala (DNr2017/289).

A single-case experimental AB design was applied and replicated across five participants. Weekly repeated measures were collected during baseline (phase A) and treatment (phase B), to compare effects between phases within subjects. The within-subject comparisons between phases serve as a control for threats against internal validity (Morley, Citation2018), while the replication across subjects strengthens external validity (Barlow et al., Citation2009). The baseline phase illustrates natural variation and should contain at least three measurement points to detect possible trends, variability, and stability (Kazdin, Citation2011). In the current study, the date of the first treatment session was set before the recruitment started, resulting in varying lengths of baselines dependent on the date of individual inclusion rather than on randomization. Hence, baselines contained either 7, 9, or 10 measurement points. The treatment phase contained 15 measurement points for all participants, and the follow-ups contained two measurement points.

Procedure

Participants were recruited between October 2017 and January 2018, through local and social media, as well as posters and referrals at local health care facilities. Participants expressed interest through email and were subsequently sent comprehensive written information about the study. If interest remained after reading the information, a structured telephone screening was conducted. Eligible participants were then invited to an on-site assessment consisting of both partners providing informed consent, a diagnostic interview with the couple around the pain, and a structured clinical interview (the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 6.0; Sheehan et al., Citation1998) with the woman. Telephone screenings and on-site assessments were held by licensed psychologists or clinical psychology students at the end of their master studies. The diagnostic interview aimed at ruling out that the pain was caused by a specific disorder and confirming that it was localized and provoked in line with the guidelines of the “2015 terminology of vulvar pain” (Bornstein et al., Citation2016). To further enhance the validity of the diagnostic interview, participants answered if they had been medically examined with a cotton swab test (Haefner et al., Citation2005) during the last year. If not, they were recommended to seek medical care to receive the test and potential diagnosis before treatment starts. Couples were included on site and separately filled out the first baseline measure through a secure digital system, with the interviewer present in the room answering questions and ensuring that no interactions occurred between the partners. Of the initial eight women assessed, one withdrew interest, and one did not meet inclusion criteria. Hence, six women were included and enrolled in treatment. Halfway through treatment, one woman chose to discontinue participation without providing a reason. Unfortunately, all efforts to contact the participant after discontinuing were unsuccessful. For a flowchart of the recruitment process, see .

Participants

Inclusion criteria were women (1) aged 18–45, (2) in a stable sexual relationship (>3 months) with a man agreeing to participate, (3) experiencing localized PVD (in accordance with the “2015 terminology of vulvar pain” (Bornstein et al., Citation2016)). Furthermore, the couple had to meet regularly (≥1 day/week or 3 times/month), and not be apart for a longer period than three consecutive weeks during treatment to enable their joint effort in regard to the treatment. Exclusion criteria were (1) ongoing physical cause explaining the condition, (2) lifelong vaginismus, (3) pregnancy or childbirth within the last year, (4) major affective disorder, psychotic disorder, substance-related disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder related to the genitals, according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), and (5) receiving concurrent psychosocial treatment for PVD.

Participant characteristics

Five participants completed treatment and were included in the analyses. Their age ranged between 19 and 37 years, and they had experienced vulvovaginal pain for 7.9 years on average. Four participants were Swedish, and one was from Finland. They had all previously sought and received help for vulvodynia. Pre-treatment, participants answered how confident they were that the treatment would improve their pain condition between 0 “Not at all” and 10 “Totally confident”, see for their answers and participant characteristics. The relationship length of the couples varied from 0.5 to 10 years, and the partners were between 20 and 52 years old.

Table 1. Participant characteristics of the women at baseline.

Treatment

The treatment was delivered between February and June 2018 and consisted of 10 two-hour group sessions for the women, and three 1-hour couple sessions with the couple alone. The group sessions were held weekly during the first half of treatment, and bi-weekly during the second half of treatment. Couple sessions were held (1) before the first group session, (2) at the middle of the treatment, and (3) after the last group session. Three months after treatment a follow-up group session was held, and 6 months after treatment a follow-up couple session was held. The treatment entailed 15 sessions in total, and the participation rate varied between 80% and 100%, see for specifics. A short telephone check-in was offered when a session was missed, to ensure treatment progress, in addition to distributing missed treatment materials. All sessions were held by two licensed psychologists, trained and supervised by the research group who developed the protocol. Protocol adherence was monitored through checklists, and all sessions were filmed for future control. The treatment content was based on an adjusted version of the protocol by Ter Kuile and Weijenborg (Citation2006). A key component throughout treatment was systematic exposure exercises for fear of pain in which participants rated their fear connected to pain-inflicting behaviors, followed by small and controlled steps of exposure to the feared situation (e.g. touching the entrance to the vagina, inserting one finger into the vagina, inserting one finger of the partner into the vagina, and having or attempting intercourse) through repetition of the behaviors until habituation of fear. Exercises were provided and recommended between all sessions. During the first half of treatment, women completed exercises by themselves. During the second half, partners were involved in the exercises. Throughout treatment, the support of the partner was emphasized. For a detailed overview of the content and exercises, see .

Table 2. Overview of the treatment.

Measures

All measures were self-report measures, filled out through a secure digital system, and provided via a link sent by e-mail to the participants. Measures of pain connected to different pain-inflicting behaviors were measured weekly during baseline and treatment phases. Additionally, participants’ sexual function, levels of pain catastrophizing, avoidance behavior, and endurance behavior were measured pre-, post- and at 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments. To assess the clinical significance of treatment effects, self-reported improvement and treatment satisfaction were measured post-treatment.

Repeated measures

Pain intensity. Pain intensity of three different pain-inflicting behaviors was measured weekly using three items from the Genital Pain Rating (GPR) questionnaire (Brauer et al., Citation2008). Participants answered how painful it had been to (1) touch the entrance to the vagina, (2) insert one finger of the partner into the vagina, and (3) have (or attempt) intercourse with their partner during the last week, on a numerical rating scale between 0 “Not painful at all” and 10 “Worst pain imaginable”. If the behavior had not been performed during the past week, participants were asked to provide an estimate of the pain. The scale has previously shown good psychometric qualities (Brauer et al., Citation2008). At the follow-up assessments, participants were asked to provide an estimate of their pain intensity connected to the three behaviors over the last 4 weeks.

Pre-, post-, and follow-up measures

Sexual function

Sexual function was assessed by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI; Rosen et al., Citation2000) consisting of 19 items assessing six domains of sexual function: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Dependent on the item, answers are given on a scale ranging from 0 or 1 to 5, where zero equals no sexual activity during the last 4 weeks. The scale ranges between 2 and 36 where a score of 26 or below indicates sexual dysfunction (Wiegel et al., Citation2005). The scale has shown good psychometric qualities (Wiegel et al., Citation2005) and has been validated in a Swedish sample (Ryding & Blom, Citation2015). In the current study, internal consistency was good with α = .96 at baseline.

Pain catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing was measured by the catastrophic and pain cognitions subscale of the Vaginal Penetration Cognition Questionnaire (VPCQ; Klaassen & Ter Kuile, Citation2009). The subscale contains five items (e.g. “I am scared that the penetration pain will get worse in the future”), answered on a scale between 0 “Not at all applicable” and 6 “Very strongly applicable”. The scale has shown good psychometric properties (Klaassen & Ter Kuile, Citation2009). In the current study, internal consistency was good with α = .92 at baseline.

Avoidance and endurance behavior

Avoidance and endurance of pain during sexual activity was measured with the CHAMP Sexual Coping Scale (CSPCS; Flink et al., Citation2015). The scale consists of two subscales with four items each; the avoidance subscale (e.g. “Because of the pain I avoid intercourse even when I feel sexually excited”) and the endurance subscale (e.g. “When I have intercourse and it is painful, I try to carry on, despite the pain“). Participants answer statements between 1 “Never true” and 7 “Always true”. Total scores of the subscales range from 4 to 28. The scale has shown good psychometric qualities in a Swedish sample (Flink et al., Citation2015). In the current study, internal consistency was good with α = .84 for the avoidance subscale and α = .70 for the endurance subscale, at baseline.

Self-reported improvement and treatment satisfaction

Participants answered to what extent they perceived an improvement regarding pain and overall quality of their sex life on a scale ranging from 0 “Deterioration” to 5 “Complete recovery (no pain)/Complete improvement (my sex life has never been better)”. Participants also rated their global treatment satisfaction on a scale ranging from 0 “Completely dissatisfied” to 10 “Completely satisfied”. Additionally, participants provided free-text answers to the question “Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience in this treatment?”.

Data analyses

Data were exported to, processed, and analyzed in Excel. Repeated measures were compiled and displayed on graphs to enable visual inspection, a standard procedure when analyzing single-case experimental design (SCED) data (Kazdin, Citation2011). Graphs were visually inspected regarding changes in mean (between phases), trend (i.e. patterns in the data), variability, level (i.e. the last point in phase A versus the first point in phase B), and overlap of data, in accordance with guidelines (Morley, Citation2018).

To further strengthen the analyses, two nonparametric quantitative approaches recommended for estimating effect sizes in SCED were calculated (Manolov et al., Citation2022). Nonoverlap of All Pairs (NAP) compares every measurement point in phase A with every measurement point in phase B, determining overlap or non-overlap, resulting in a percentage of non-overlapping data (Parker & Vannest, Citation2009). NAP has been shown to be robust but is sensitive to trends in the baseline (Manolov et al., Citation2022). Tau-U shows improvement in data points from baseline to treatment by calculating between- and within-phase trends, dividing the net improvement sum by the number of pairs in the data. Tau-U enables controlling for possible baseline trends and expresses trends in the data as a percentage of data that improve over phases (Parker et al., Citation2011). In the current study, controlling for baseline trends by correcting them was made when Tau-U for the baseline was .4 or above (Brossart et al., Citation2018). NAP and Tau-U were calculated using the same online calculator (Vannest et al., Citation2016), including confidence intervals and p-values. Yet, these should be interpreted cautiously as they build on assumptions of independency which could be questioned in SCED data (Manolov et al., Citation2022).

Results

Repeated measures

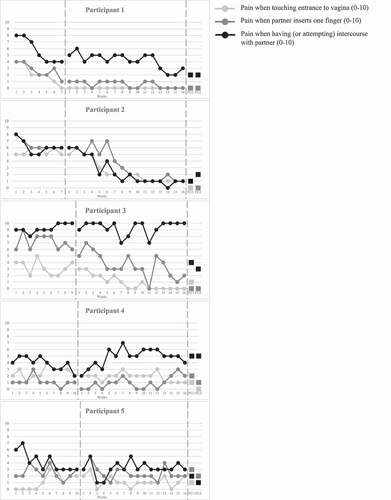

All measures were completed by the participants. Weekly measures of pain intensity connected to three different pain-inflicting behaviors are displayed in individual graphs in . As can be seen, baselines are stable, except for Participant 5 who displays high variability in both baseline and treatment phase making the results difficult to interpret. Furthermore, there are clear signs of baseline trends in some instances. Participant 1 shows baseline trends in all three pain-inflicting behaviors, and Participant 5 shows regarding intercourse pain. This was further supported by the Tau-U calculations showing baseline trends (≥.4), in the baselines of Participants 1 and 5, as well as in the baseline of Participant 2 regarding pain when partner inserts one finger and Participant 4 regarding intercourse pain.

Pain when touching the entrance of the vagina

Visual analysis of repeated measures of pain when touching the entrance of the vagina shows trends of improvement for Participants 1, 2 and 3, further supported by significant NAP and Tau-U scores, see . The mean decreased between the phases for all participants except for Participant 5. Scores at the two follow-up assessments were low and stable for all participants.

Table 3. Repeated measures on pain when touching the entrance of the vagina (0–10) for each participant.

Pain when partner inserts one finger into the vagina

Visual analysis of weekly measures of pain when partner inserts one finger into the vagina shows improvement in pain for Participants 1, 2 and 3, further supported by significant NAP and Tau-U scores, see . The mean decreased between the phases for all participants except for Participant 4 and scores at the follow-ups were consistently low except for Participants 4 and 5.

Table 4. Repeated measures on pain when partner inserts one finger into the vagina (0–10) for each participant.

Pain when having (or attempting) intercourse

There was a slight improvement in intercourse pain for Participant 1, and a clear improvement for Participant 2, supported by significant NAP and Tau-U scores for Participant 2, see . Variability was high during both phases for Participants 3 and 5, making results hard to interpret. Participant 4 showed an increase in intercourse pain implicating deterioration, supported by a significant Tau-U score in the undesired direction. The mean decreased between phases for Participants 1, 2, and 5. Follow-up scores followed the same pattern, except for Participant 3 who improved at both follow-ups.

Table 5. Repeated measures on pain when having (or attempting) intercourse with partner (0–10) for each participant.

Pre-, post-, and follow-up measures

shows descriptive statistics of pre-, post-, and follow-up scores on sexual function, pain catastrophizing, aavoidance,and endurance behavior, as well as changes in percentage between pre-measure and 6-month follow-up.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of pre-, post- and follow-up measurements of each participant.

Participants 1, 2, 3 and 5 improved their sexual function between the pre- and post-measures, while Participant 4 reported a lowered score on sexual function. However, a low score on the FSFI may indicate no sexual activity (Rosen et al., Citation2000), making it hard to distinguish between an actual decrease in function and a lack of sexual activity. Participant 3 got pregnant between the post- and follow-up assessments, possibly affecting the two follow-up measurements.

Participants 1, 2 and 3 showed reductions in pain catastrophizing during treatment, while Participant 4 showed a great increase and Participant 5 a small increase. All participants lowered their levels of avoidance behavior between the pre- and post-measure except for Participant 4 who showed a slight increase. Lastly, all participants reported decreased levels of endurance behavior post-treatment.

Self-reported improvement and treatment satisfaction

shows participants’ ratings on their subjective improvement and overall treatment satisfaction. Participants generally rated their improvement as moderate or great regarding both pain and quality of sex life. This mirrors the results from the visual analysis and calculations, thus strengthening the clinical significance of the findings. The only participant rating improvements as small was Participant 4 whose results also implicate that the treatment was not helpful regarding pain.

Table 7. Self-reported improvement and treatment satisfaction.

Participants generally rated treatment satisfaction as high (M = 8.8). Some participants chose to share free-text answers about their experience of the treatment: “Very nice group where I felt safe to talk about everything. Professional psychologists, and good in terms of structure and content.” (Participant 3), “It was intense, but very much worth it. Even if I’m not completely free of my problems I’ve gained new understandings of them. I’ve understood that I can do something about them, that it’s possible for me to get better” (Participant 5) and “I’ve learned an incredible amount from this study, and I’m so grateful for everything I’ve learned from everyone involved” (Participant 4).

Discussion

This initial proof of concept shows promising—yet ambiguous—results of the CBT group treatment with partner involvement for women suffering from PVD. Three out of five women showed improvements, one showed no improvement or a slight deterioration, whereas we could not draw any conclusion about the fifth participant due to large variability in ratings. More specifically, Participants 1, 2 and 3 improved in pain ratings, both when touching the entrance of the vagina, and when the partner inserted one finger into the vagina. Participants 1 and 2 improved in intercourse pain post-treatment, and Participant 3 followed a similar pattern at follow-up. Participant 4 showed no improvement during treatment in any of the three pain-inflicting behaviors, but rather got worse in ratings of intercourse pain. Lastly, Participant 5 demonstrated high variability in all three behaviors during both phases, making the results hard to decipher. The visual analyses were supported by the NAP and Tau-U calculations, further strengthening the conclusions.

Overall, these results suggest that for some women, but not for all, it is possible to target and conceivably change pain linked to specific behaviors by systematic exposure exercises targeting covert (endurance) and overt avoidance. The follow-up assessments further suggest the potentiality to generalize improvements up to 6 months after treatment for these women. The pre-, post-, and follow-up assessments of sexual function, pain catastrophizing, avoidance, and endurance behavior indicate that the treatment may also have succeeded in addressing psychological and behavioral factors, pinpointed as central for maintaining PVD (Bergeron et al., Citation2015; Desrochers et al., Citation2008, Citation2009). Yet, it is still to explore the characteristics of women benefiting from the treatment, as opposed to the ones who did not improve.

Beyond apparent limitations when comparing results of group designs and single-case designs, the results could be considered to be in agreement with earlier studies investigating the effect of CBT on PVD (see, e.g. Rosen et al., Citation2019). Specifically, the study by ter Kuile and Weijenborg, previously evaluating the protocol (Ter Kuile & Weijenborg, Citation2006), showed comparable decreases in intercourse pain (8.0 to 6.8 on a 0–10 scale) in average post treatment. While not measuring sexual function directly, the study found significant reductions in sexual dissatisfaction (Ter Kuile & Weijenborg, Citation2006). As an initial proof of concept examining the adjusted and enhanced protocol, the improvements found in three out of five women further validate the protocol. Nevertheless, as two of the women did not show corresponding improvements, our findings also point at considerable variability in variability in treatment response - variability possibly hidden in traditional group data.

While the treatment format, involving group sessions and complementary couple sessions, as well as the relational focus and emphasis on the support and involvement of the partner, is a novel aspect of the study, an evaluation of their specific effects was outside the scope of the current study. However, the results suggest that this treatment format may be beneficial. Future studies should investigate possible benefits of different treatment formats and partner outcomes.

The treatment targets key psychological and behavioral factors identified in women with PVD, such as pain catastrophizing and avoidance behavior. The avoidance in this pain group may both be reflected in a generalized avoidance of sexual or pain-provoking activities, but also an avoidance of letting the partner or oneself down by rejecting sex, resulting in endurance of sexual activities despite pain (Engman et al., Citation2018; Flink et al., Citation2017). This treatment addresses both types of avoidance behaviors through systematic exposure, integrated with a clear message that pain-inflicting activities are prohibited during treatment. This is in line with the fear-avoidance model of pain (Vlaeyen & Linton, Citation2000), as well as earlier research on avoidance and endurance behavior showing that both behavioral patterns may be conceptualized as avoidance as they are used interchangeably rather than separately (Engman et al., Citation2018). Taken together, these findings signal that treatments addressing these behavioral patterns through systematic exposure exercises and pain prohibition may benefit women with PVD.

The repeated measures reflect behaviors actively targeted during treatment via systematic exposure exercises. The results indicate that for three out of five participants, the exposure may have been effective. Still, for most participants, intercourse pain did not change. This may be because improvements take considerable time, possibly more time than covered between pre- and post-assessments. This is supported by the fact that all participants, except for one, rated their intercourse pain as improved at both follow-up assessments.

One participant (Participant 4) deteriorated in pain ratings, while levels of pain catastrophizing, avoidance, and endurance increased substantially. Nevertheless, in the treatment evaluation, this participant stated that “I’ve learned an incredible amount from this study, and I’m so grateful for everything I’ve learned from everyone involved”, in addition to rating the treatment overall as good. Deterioration after psychological treatment is an understudied area worthy of more attention (Barlow, Citation2010). The single-case methodology could serve as a useful tool for the close monitoring of treatment effects, both positive and negative. Regarding the participant in the current study, an alternative explanation than actual deterioration, suggested by the psychologists leading the group, is that these conflicting results reflect a process of increased awareness and exposure to pain. If so, the level of awareness is an important aspect to include in future evaluations in addition to the continued investigation of adverse effects of psychological treatment.

The present study is the first investigation of this treatment and a precursor for future investigations. The high participation rates, the positive self-reported improvements, and treatment satisfaction, in combination with the overall improvements for three out of five women, suggest that the “concept” is functional and that no substantial alterations are needed if evaluating the treatment further in a future RCT.

Although a replicated SCED study has considerable internal validity due to each participant serving as her own control (Morley, Citation2018), the study has some shortcomings. Randomization to baseline lengths was not possible due to the group format and a set treatment start, implying a reduction in internal validity and strength of conclusions even though the recruitment process resulted in natural variation of baseline lengths. Trends and variability in baselines are other threats to internal validity, creating difficulties in interpreting whether participants would have improved without intervention. As previously mentioned, the use of effect sizes and complementary statistics such as p-values and confidence intervals should be used and interpreted cautiously since these techniques build on assumptions often not met by SCED data (Manolov et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, there is a risk of inflated effect sizes when calculated on small samples (Maggin et al., Citation2017) which has to be acknowledged. To further strengthen internal validity, treatment adherence should have been measured and evaluated. Both from the perspective of those delivering treatment and those receiving it.

The limited number of participants should also be considered, naturally threatening external validity and the possibility to generalize findings, not the least since two of the participants did not show considerable improvements. Similarly, women in this study may be different from women seeking help for PVD as they were self-selected volunteers. Being in a stable sexual relationship with a man willing to participate was a prerequisite for inclusion, resulting in a selected group of PVD sufferers. If proven successful in future investigations, the treatment needs to be adjusted to suit the heterogenic group of women with PVD.

Finally, the single-case design enables the highlighting of individuality and heterogeneity, both between and within individuals—positive in regard to dissecting individual function and problematic in regard to drawing strong and conclusive conclusions. Combined with the wide diversity and heterogeneity within the group of vulvodynia sufferers (Corsini-Munt et al., Citation2017), treatment delivery and interpretation of the results must be made cautiously and with close monitoring of possible adverse treatment effects. Despite some methodological shortcomings, this study nevertheless provides the first detailed data showing the relevance of this treatment and points at the need for larger and controlled studies.

Taken together, this CBT group treatment with partner involvement for PVD showed promising yet non-conclusive results. Pain associated with three pain-inflicting behaviors decreased in three out of five participants. Associated outcomes changed over time, indicating the potential for influencing important psychological factors in pain maintenance. The findings suggest that this treatment may be a viable and promising path forward, well worth exploring further in larger and controlled studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5. ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Barlow, D. H., Nock, M., & Hersen, M. (2009). Single case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior for change (3. ed.). Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

- Barlow, D. H. (2010). Negative effects from psychological treatments: A perspective. The American Psychologist, 65(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015643

- Bergeron, S., Corsini-Munt, S., Aerts, L., Rancourt, K., & Rosen, N. O. (2015). Female sexual pain disorders: A review of the literature on etiology and treatment. Current Sexual Health Reports, 7(3), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-015-0053-y

- Bergeron, S., Merwin, K. E., Dubé, J. P., & Rosen, N. O. (2018). Couple sex therapy versus group therapy for women with genito-pelvic pain. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(3), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-018-0154-5

- Bergeron, S., Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Corsini-Munt, S., Steben, M., Delisle, I., Mayrand, M.-H., & Rosen, N. O. (2021). Cognitive-Behavioral couple therapy versus lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(4), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000631

- Bohm-Starke, N., Ramsay, K. W., Lytsy, P., Nordgren, B., Sjöberg, I., Moberg, K., & Flink, I. (2022). Treatment of provoked vulvodynia: A systematic review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 19(5), 789–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.02.008

- Bornstein, J., Goldstein, A. T., Stockdale, C. K., Bergeron, S., Pukall, C., Zolnoun, D., & Coady, D. (2016). 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(4), 607–612. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001359

- Brauer, M., Ter Kuile, M. M., Laan, E., & Trimbos, B. (2008). Cognitive-Affective correlates and predictors of superficial dyspareunia. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 35(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12697

- Brauer, M., Lakeman, M., van Lunsen, R., & Laan, E. (2014). Predictors of task-persistent and fear-avoiding behaviors in women with sexual pain disorders. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(12), 3051–3063. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230802525604

- Brossart, D. F., Laird, V. C., Armstrong, T. W., & Walla, P. (2018). Interpreting Kendall’s Tau and Tau- U for single-case experimental designs. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1518687. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1518687

- Brotto, L. A., Bergeron, S., Zdaniuk, B., & Basson, R. (2020). Mindfulness and cognitive behavior therapy for provoked vestibulodynia: Mediators of treatment outcome and long-term effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000473

- Corsini-Munt, S., Rancourt, K. M., Dubé, J. P., Rossi, M. A., & Rosen, N. O. (2017). Vulvodynia: A consideration of clinical and methodological research challenges and recommended solutions. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 2425–2436. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S126259

- Danielsson, I., Sjöberg, I., Stenlund, H., & Wikman, M. (2003). Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: Results from a population study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 31(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/%2F14034940210134040

- Desrochers, G., Bergeron, S., Landry, T., & Jodoin, M. J. (2008). Do psychosexual factors play a role in the etiology of provoked vestibulodynia? A critical review. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 34(3), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819976e3

- Desrochers, G., Bergeron, S., Khalife, S., Dupuis, M. J., & Jodoin, M. (2009). Fear avoidance and self-efficacy in relation to pain and sexual impairment in women with provoked vestibulodynia. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 25(6), 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230701866083

- Elmerstig, E., Wijma, B., & Swahnberg, K. (2013). Prioritizing the partner’s enjoyment: A population-based study on young Swedish women with experience of pain during vaginal intercourse. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 34(2), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2013.793665

- Engman, L., Flink, I., Ekdahl, J., Boersma, K., & Linton, S. J. (2018). Avoiding or enduring painful sex? a prospective study of coping and psychosexual function in vulvovaginal pain. European Journal of Pain, 22(8), 1388–1398. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1227

- Flink, I. K., Thomten, J., Engman, L., Hedström, S., & Linton, S. J. (2015). Coping with painful sex: Development and initial validation of the CHAMP sexual pain coping scale. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 9(1), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12093

- Flink, I. K., Engman, L., Thomtén, J., & Linton, S. J. (2017). The role of catastrophizing in vulvovaginal pain: Impact on pain and partner responses over time. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 22(1), e12093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.05.002

- Goldstein, A. T., Pukall, C. F., Brown, C., Bergeron, S., Stein, A., & Kellogg-Spadt, S. (2016). Vulvodynia: Assessment and treatment. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(4), 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.020

- Haefner, H. K., Collins, M. E., Davis, G. D., Edwards, L., Foster, D. C., Hartmann, E., Kaufman, R. H., Lynch, P. J., Margesson, L. J., Moyal-Barracco, M., Piper, C. K., Reed, B. D., Stewart, E. G., & Wilkinson, E. J. (2005). The vulvodynia guideline. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 9(1), 40–51.

- Harlow, B. L., & Stewart, E. G. (2003). A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: Have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 58(2), 82–88. PMID: 12744420.

- Harlow, B. L., Kunitz, C. G., Nguyen, R. H., Rydell, S. A., Turner, R. M., & MacLehose, R. F. (2014). Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: Population-based estimates from 2 geographic regions. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 210(1), 40.e1–40.e08. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.033

- Kazdin, A. E. (2011). Single-Case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings (2. ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Klaassen, M., & Ter Kuile, M. M. (2009). Development and initial validation of the vaginal penetration cognition questionnaire (VPCQ) in a sample of women with vaginismus and dyspareunia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(6), 1617–1627. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01217.x

- Landry, T., & Bergeron, S. (2011). Biopsychosocial factors associated with dyspareunia in a community sample of adolescent girls. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 877–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9637-9

- Maggin, D. M., Lane, K. L., & Pustejovsky, J. E. (2017). Introduction to the special issue on single-case systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Remedial and Special Education, 38(6), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932517717043

- Manolov, R., Moeyaert, M., & Fingerhut, J. E. (2022). A priori justification for effect measures in single-case experimental designs. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 45(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-021-00282-2

- Morley, S. (2018). Single case methods in clinical psychology: A practical guide. Routledge.

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.). (2018, February). CBT group treatment for women with dyspareunia. Identifier NCT03427255. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03427255

- Parker, R. I., & Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.006

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.006

- Pukall, C. F., Mitchell, L. S., & Goldstein, A. T. (2016). Non-Medical, medical, and surgical approaches for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8(4), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-016-0093-y

- Reed, B. D., Harlow, S. D., Sen, A., Legocki, L. J., Edwards, R. M., Arato, N., & Haefner, H. K. (2012). Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 206(2), 170.e171–170.e179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012

- Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., Ferguson, D., & D’Agostino, R., Jr. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278597

- Rosen, N. O., Dawson, S. J., Brooks, M., & Kellogg-Spadt, S. (2019). Treatment of vulvodynia: Pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Drugs, 79(5), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-019-01085-1

- Ryding, E. L., & Blom, C. (2015). Validation of the Swedish version of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12778

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8

- Ter Kuile, M. M., & Weijenborg, P. T. M. (2006). A cognitive-behavioral group program for women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome (VVS): Factors associated with treatment success. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 32(3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230600575306

- Ter Kuile, M. M., Both, S., & van Lankveld, J. J. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women. Psychiatric Clinics, 33(3), 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.010

- Thomtén, J., & Linton, S. J. (2013). A psychological view of sexual pain among women: Applying the fear-avoidance model. Women’s Health, 9(3), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.2217/%2FWHE.13.19

- Van Lankveld, J. J., Granot, M., Schultz, W. C. W., Binik, Y. M., Wesselmann, U., Pukall, C. F., Bohm-Starke, N., & Achtrari, C. J. T. (2010). Women’s sexual pain disorders. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(1), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01631.x

- Vannest, K. J., Parker, R. I., Gonen, O., & Adiguzel, T. (2016). Single case research: Web based calculators for SCR analysis. (Version 2.0) [Web-based application]. Texas A&M University. Retrieved September 16, 2021, from singlecaseresearch.org

- Vlaeyen, J. W., & Linton, S. J. (2000). Fear-Avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain, 85(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0

- Wiegel, M., Meston, C., & Rosen, R. (2005). The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 31(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230590475206