ABSTRACT

Most people with a mental disorder meet criteria for multiple disorders. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing psychotherapies for people with depression and comorbid other mental disorders with non-active control conditions. We identified studies through an existing database of randomized trials on psychotherapies for depression. Thirty-five trials (3,157 patients) met inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven of the 41 interventions in the 35 trials (66%) were based on CBT. The overall effect on depression was large (g = 0.65; 95% CI: 0.40 ~ 0.90), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 78%; 95% CI: 70 ~ 83). The ten studies in comorbid anxiety showed large effects on depression (g = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.30 ~ 1.51) and anxiety (g = 1.01; 95% CI: 0.28 ~ 1.74). For comorbid insomnia (11 comparisons) a large and significant effect on depression (g = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.16 ~ 1.82) and insomnia (g = 1.38; 95% CI: 0.38 ~ 2.38) were found. For comorbid substance use problems (12 comparisons) effects on depression (g = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.06 ~ 0.43) and on substance use problems (g = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.01 ~ 0.50) were significant. Most effects were no longer significant after adjustment for publication bias and when limited to studies with low risk of bias. Therapies are probably effective in the treatment of depression with comorbid anxiety, insomnia, and substance use problems.

Introduction

Depressive disorders are highly prevalent and are associated with considerable loss of quality of life for patients and their relatives, with increased levels of morbidity and mortality, and with enormous economic costs for society (Herrman et al., Citation2022). Several antidepressants and psychological interventions have been found to be effective in the treatment of depression (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Cuijpers, Quero, et al., Citation2021). However, the effects of these treatments have not been tested extensively in patients with other comorbid mental disorders, while comorbidity is the norm among depression, as it is among other common mental disorders (Demyttenaere et al., Citation2004; Kessler et al., Citation2005).

More than 50% of people with a mental disorder in a given year meet criteria for multiple disorders, and it has been estimated that about a quarter meets criteria for 3 or more diagnoses (Demyttenaere et al., Citation2004; Kessler et al., Citation2005). Most people who are diagnosed with depression have a comorbid anxiety and/or substance use disorder (Herrman et al., Citation2022) and that is true in community epidemiological surveys (Wanders et al., Citation2016), in primary care (Kotiaho et al., Citation2019), and in specialized mental healthcare settings (Lamers et al., Citation2011). But many patients with a depressive disorder have often also other mental disorders, including insomnia (Staner, Citation2010), borderline personality disorder (Beatson & Rao, Citation2013), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Rytwinski et al., Citation2013).

Currently, more than 800 trials have examined the effects of psychological treatments of depression (Cuijpers & Karyotaki, Citation2020), and several meta-analyses have focused on the effects of these treatments on comorbid mental health problems, such as anxiety (Weitz et al., Citation2018), insomnia (Ye et al., Citation2015) and suicidality (Cuijpers et al., Citation2013). However, to examine whether psychological treatments are effective in people with other comorbid mental disorders, trials are needed in which participants meet criteria for both depression and the comorbid mental disorder at baseline. That is necessary because only these trials can show whether psychological treatments are indeed effective in these populations. None of these previous meta-analyses focused on this type of studies, and only examined the effects on comorbid mental health problems in the total population of depressed participants, regardless of whether they met diagnostic criteria for the comorbid disorder at baseline.

In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, we will focus on studies examining the effects of psychological treatments compared with control groups in participants who meet criteria for depression as well as criteria for other comorbid mental disorders. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis focusing on trials among people with comorbid depression and other mental disorders.

Methods

Identification and selection of studies

The current study is part of a larger meta-analytic project on psychological treatments of depression that was registered at the Open Science Framework (Cuijpers & Karyotaki, Citation2020; doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/825C6) and supplemental materials are available at the website of the project (www.metapsy.org/depression-psychotherapy). The protocol for the current meta-analysis has been published at the Open Science Framework, before the end of the data extraction and before the start of the analyses (Cuijpers, Citation2021). The studies included in the current study were identified through the larger, already existing database of randomized trials on the psychological treatment of depression. This database has been used in a series of earlier published meta-analyses (Cuijpers, Citation2017). For this database, we searched four major bibliographical databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and the Cochrane Library) by combining index and free text terms indicative of depression and psychotherapies, with filters for randomized controlled trials. The full search strings can be found at the website of the project (https://protectlab.shinyapps.io/depressionShinyWebsite/search_strings.pdf). Furthermore, we checked the references of earlier meta-analyses on psychological treatments of depression. The database is continuously updated and was developed through a comprehensive literature search (from 1966 to January 1,st 2022). All records were screened by two independent researchers and all papers that could possibly meet inclusion criteria according to one of the researchers were retrieved as full-text. The decision to include or exclude a study in the database was also done by the two independent researchers, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

For the current study, we included randomized controlled trials in which a psychological intervention was compared with a control condition (waitlist, care-as-usual, or other non-active control) in people with both depression (according to a diagnostic interview or a score above the cut-off of a self-report depression measure) and a comorbid mental health problem (also according to a diagnostic interview or a score above the cut-off of a self-report measure). We included psychological interventions primarily targeting either depression, the comorbid disorder, or both. We included trials with any comorbid mental health problem. Studies in people with general medical disorders (including dementia) were not included, also because these studies have been examined in a recent meta-analysis by our group (Miguel et al., Citation2021). We also included studies in which all participants in the intervention and control group received antidepressants, because these studies do allow to estimate the unique effects of the psychotherapy. We only included individual, group and guided self-help interventions. Interventions without any human interaction were not included, because these have been found to be less effective than other treatment formats (Cuijpers et al., Citation2019; Karyotaki, et al., Citation2017, Citation2021). We excluded studies in which two therapies were compared with each other and no control group was available. We also excluded trials aimed at one single disorder.

Quality assessment and data extraction

We assessed the validity of included studies using four criteria of the “Risk of bias” (RoB) assessment tool, version 1, developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins et al., Citation2011). We used version 1 of this tool because this meta-analysis is part of a yearly updated meta-analytic database, for which it is not required to use the updated RoB 2 tool (Sterne et al., Citation2019).

The RoB tool assesses possible sources of bias in randomized trials, including the adequate generation of allocation sequence; the concealment of allocation to conditions; the prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (masking of assessors); and dealing with incomplete outcome data (this was assessed as positive when intention-to-treat analyses were conducted, meaning that all randomized patients were included in the analyses). Assessment of the validity of the included studies was conducted by two independent researchers, and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We also coded participant characteristics (comorbid mental health problem; diagnostic method; recruitment method; generic versus specific target group; mean age; proportion of women); characteristics of the psychological treatments (type of therapy; treatment format; number of sessions) as well as the main focus of the intervention (depression, comorbid mental disorder, or both); and general characteristics of the studies (type of control group; publication year; country where the study was conducted).

Outcome measures

For each comparison between a psychological treatment and a control condition, the effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post-test was calculated (standardized mean difference corrected for small-sample bias; Hedge's g; Hedges & Olkin, Citation1985). Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting (at post-test) the average score of the psychotherapy group from the average score of the control group and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation. Because some studies had relatively small sample sizes we corrected the effect size for small sample bias. When means and standard deviations were not reported we calculated the effect size using dichotomous outcomes; and if these were not available either, we used other statistics (such as t-value or p-value) to calculate the effect size.

For each study, we calculated the effect size indicating the effects of the intervention on depression as well as on the comorbid mental health problem. For depression, we selected the outcome measure based on an algorithm that we used in a previous meta-analysis on psychotherapies for depression, giving priority to the HAM-D-17, the BDI, the BDI-II, another clinician-rated instrument and another self-report instrument (Cuijpers et al., Citation2020). For the comorbid mental health problems, we selected the main outcome reported in the study or if more than one outcome was reported, the outcome that was reported in the majority of trials. When this was not possible, we used the first main outcome that was reported in the description of outcome measures. Effect sizes were calculated using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 3.3070; CMA).

Meta-analyses

To calculate pooled mean effect sizes, we used the “meta” (Balduzzi et al., Citation2019), “metafor” (Viechtbauer, Citation2010) and “dmetar” (Harrer et al., Citation2022) packages in R (version 4.1.1) and conducted all analyses in R studio (version 1.1.463 for Mac). Because we expected considerable heterogeneity among the studies, we employed a random effects pooling model in all analyses. We used the inverse variance method for pooling effect sizes with the Hartung-Knapp adjustment for the random effects model. The between-study heterogeneity variance was calculated with the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) estimator.

We calculated the pooled effect sizes for each comorbid disorder separately, but for depression we also calculated the pooled effect size for all trials together, because they are all aimed also at people suffering from depression. We conducted subgroup analyses to examine the differences between the comorbid disorders in terms of effects on depression. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to a mixed-effects model, in which studies within subgroups were pooled with a random-effects model, while tests for differences between subgroups were conducted with a fixed-effects model.

Because we did not expect large numbers of studies in each of the subgroups of comorbid disorders, we planned to conduct only a limited number of exploratory subgroup analyses. Apart from the subgroup analyses examining the differential effect of therapies for the identified comorbid disorders, we also conducted subgroup analyses for the subgroups indicating if a diagnostic interview was used to establish the presence of the disorder, if the intervention was aimed at depression, at the comorbid disorder or at both, and for type of control condition. We avoided subgroups with less than 3 studies.

In addition to Hedges’ g, we also calculated Numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT) for depression using the formulae provided by Furukawa et al. (Citation2005), in which the control group’s event rate was set at a conservative 16% (based on the pooled response rate of 50% reduction of symptoms across trials in psychotherapy for depression) (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021). We did not calculate NNTs for the outcomes on the comorbid mental health problems, because the control group’s outcome rates are unknown.

As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I2-statistic and its 95% confidence interval, which is an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values indicate increasing heterogeneity, with 25% as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity (Higgins et al., Citation2003). Because the 95% CI of the effect size does not indicate how the true effects found in studies are distributed, we also added the prediction interval which indicates the range in which the true effect size of 95% of all populations will fall (Borenstein et al., Citation2009; Borenstein et al., Citation2017).

We tested for publication bias (small sample bias) by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000), which yields an estimate of the effect size after correction for the funnel plot asymmetry. We also used two other methods to examine the potential impact of publication bias: Rücker’s “limit meta-analysis method” (Rücker et al., Citation2011), and the three-parameter selection model (Carter et al., Citation2019; McShane et al., Citation2016).

We also conducted Egger’s test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and to test whether it was significant. The RRs indicating incidence and acceptability of the interventions were pooled across studies, with the Hartung and Knapp method used to adjust test statistics and confidence intervals, and an increment of 0.1 added for studies with a zero-cell count.

We conducted sensitivity analyses: (1) in which we limited the analyses to studies with low risk of bias (low risk for all four items of the risk of bias tool); (2) analyses in which outliers were excluded. We defined outliers according to “non-overlapping confidence intervals” approach, in which a study is defined as an outlier when the 95% CI of the effect size does not overlap with the 95% CI of the pooled effect size (Harrer et al., Citation2022).

Results

Selection and inclusion of studies

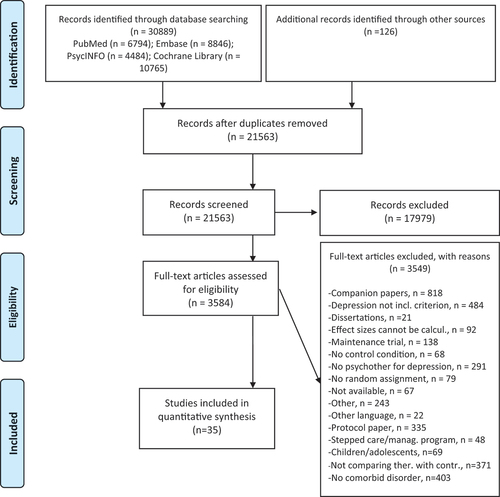

After examining a total of 30,889 records (21,563 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 3,584 full-text papers for further consideration. We excluded 3,549 of the retrieved papers. The PRISMA flowchart describing the inclusion process, including the reasons for exclusion, is presented in . A total of 35 randomized controlled trials (with 41 comparisons between a psychotherapy and a control group) met inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included studies

A summary of key characteristics of the 35 included studies is presented in . In the trials, 3,157 patients participated, 1,822 in the intervention and 1,335 in the control conditions. Ten studies were aimed at comorbid insomnia, nine on anxiety, and eight on substance use problems. The remaining eight studies were aimed at psychotic disorders (two studies), PTSD (two), autism, borderline personality disorder (BPD), OCD, and suicide (each one study). The two studies on PTSD that were included were not directly aimed at PTSD but included women with depression and a history of childhood trauma (Vitriol et al., Citation2009) and depressed women with sexual abuse histories (Talbot et al., Citation2011). In both studies, the proportion of participants with PTSD was more than 59%, and we included them because all participants had at least a key symptom of PTSD.

Table 1. Selected characteristics of included studies.

In 21 trials participants met criteria for a depressive disorder according to a diagnostic interview, while the other 14 trials included participants who scored above a cut-off on a self-report depression scale. In 17 trials the comorbid condition was established with a diagnostic interview, and in 13 studies both depression and the comorbid condition was established with a diagnostic interview. In 10 studies, usual care was used as control group, 7 studies used pharmacotherapy-only as control (all participants in the psychotherapy groups also received pharmacotherapy), 5 used a waitlist control group and the 13 remaining studies used a mix of other non-active control groups. Thirteen studies were conducted in North America, 8 in Europe, 6 in Australia, 4 in East Asia, and 4 in other countries.

The 35 trials included 41 interventions arms that were compared with a control group. Twenty-one of the 41 interventions were aimed at both depression and the comorbid condition, 10 were aimed specifically at the comorbid condition and 10 were aimed at depression. Most intervention arms examined CBT (27), 4 used third wave therapies, 3 psychodynamic therapy, 3 interpersonal psychotherapy, and 4 another type. Twenty interventions had an individual format (including one telephone-based intervention), nine had a group format, 7 a guided self-help format and the remaining 5 studies had a mixed format. The number of sessions ranged from 2 to 27, with the majority (23 interventions) between 6 and 12 sessions.

Twenty-one of the 35 studies reported an adequate sequence generation (60.0%); 17 reported allocation to conditions by an independent party (48.6%); 12 reported using blinded outcome assessors (34.3%) while 17 used only self-report outcomes (48.6%). In 30 studies, intent-to-treat analyses were conducted (85.7%). Thirteen studies (37.1%) met all criteria for low risk of bias, 17 studies (48.6%) met 2 or 3 criteria, and 5 met only one criterion (14.3%).

Effects of psychological interventions on depressive symptomatology

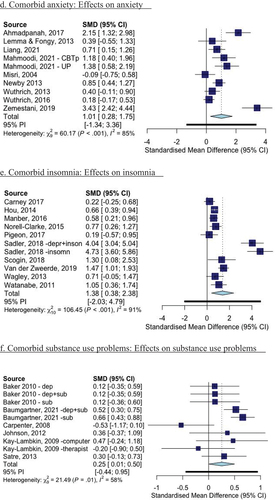

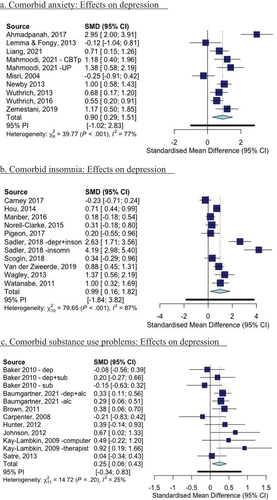

The effects of psychotherapies for depression and comorbid disorders with depression as outcome are reported in . gives the forest plots for the effects of psychotherapies for depression and comorbid disorders, separately for comorbid anxiety, comorbid insomnia, and comorbid substance use problems (with depressive symptomatology as outcomes).

Figure 2. Forest plots of the effects of psychotherapies for depression and comorbid other mental disorders: Effects on depression and comorbidities.

Table 2. Effects of psychotherapies on depression across the three major comorbid disorders.

The pooled effect size of all psychotherapies for depression and any comorbid mental disorder was g = 0.65 (95% CI: 0.40 ~ 0.90), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 78; 95% CI: 70–83). This corresponds with a NNT of 4.87. It was somewhat smaller when outliers were excluded (g = 0.53; 95% CI: 0.39 ~ 0.68). In studies with low risk of bias the effects were similar to the main analyses (g = 0.59; 95% CI: 0.25 ~ 0.92). This was also true for the analyses in which each study contributed only one arm (). The effects were still significant after adjustment for publication using the trim and fill procedure and the selection method, but not after adjustment through the limit method.

We conducted subgroup analyses for all studies together but did not find significant differences for studies focusing on depression, on the comorbid disorder or on both (p = 0.49; ). We also did not find significant differences for studies in which depression was established with a clinical interview (p = 0.12), or for studies in which the comorbid condition was established with a clinical interview (p = 0.77). We also conducted a subgroup analysis for the effects on depression for the four groups of comorbid conditions (anxiety, insomnia, substance use problems, other; not reported in a Table), and found that the effects on depression differed significantly across these groups (p = 0.01).

Effects of psychological interventions for comorbid disorders on depression

Comorbid anxiety disorders

In the ten studies in which patients had comorbid anxiety, the effect of the therapies on depression was large and comparable with the main analyses of all studies combined (g = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.29 ~ 1.51; NNT = 3.31; I2 = 77; 95% CI: 59 ~ 88), and significant (). The effects were not significant anymore in any of the three methods to adjust for publication bias and when we only included studies with low risk of bias (g = 1.59; 95% CI: −0.68 ~ 3.87). The effects did not materially differ from the main analyses in the other sensitivity analyses. Heterogeneity was moderate to high in all analyses (range I2: 59 ~ 86).

Table 3. Effects of psychotherapies on depression separately for the three major comorbid disorders.

All interventions were aimed at depression and anxiety simultaneously, so we could not do a subgroup analysis on the focus of the intervention. We did conduct a subgroup analysis comparing the studies in which participants met criteria for a depressive disorder with those in which participants scored above a cut-off score on a depression scale. We also conducted a subgroup analysis for studies in which participants met criteria for an anxiety disorder versus a cut-off on a self-report scale. Both subgroup analyses did not indicate significant differences between subgroups.

Comorbid insomnia

The 11 comparisons from 10 studies on comorbid depression and insomnia showed a large and significant effect on depression (g = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.16 ~ 1.82; NNT = 2.96) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 87; 95% CI: 80 ~ 92) (). However, the effects were no longer significant after adjusting for publication bias (all three methods) and the studies with low risk of bias also did not point at a significant effect (g = 0.74; 95% CI: −0.24 ~ 1.72; 4.17). The effects did remain significant in most other sensitivity analyses. The subgroup analyses did not point at significant differences between any of the subgroups (there were not enough studies to do a subgroup analysis for focus of the intervention). Heterogeneity was very high in most analyses (range I2: 80 ~ 91), except for the studies with low risk of bias (I2 = 30).

Comorbid substance use problems

The 12 comparisons from 8 studies in patients with comorbid depression and substance use problems resulted in a small, but significant effect size on depressive symptoms (g = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.06 ~ 0.43; NNT = 14.64) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 25; 95% CI: 0 ~ 62) (). The effects were still significant after adjustment for publication bias through the trim and fill procedure, but not after adjustment using the other two methods. Limiting the studies to those with low risk of bias, also resulted in a non-significant effect size (g = 0.21; 95% CI: −0.03 ~ 0.46). Heterogeneity was low in all analyses (range I2: 21–31).

None of the subgroup analyses indicated a significant difference between subgroups, although there were not enough studies in which participants met criteria for depressive disorders.

Effects on anxiety, insomnia and substance use problems

The effects of psychotherapies for depression and comorbid disorders with the comorbid mental health problems as outcome are reported in and forest plots are given in .

Table 4. Effects of psychotherapies on comorbid disorders.

The effects of the interventions on the comorbid mental health problems were very comparable to the effects of the interventions on depression. The effects on anxiety were large and significant (g = 1.01; 95% CI: 0.28 ~ 1.74), but no longer significant after adjustment for publication bias in two of the three adjustment methods, and when limiting to studies with low risk of bias (g = 1.59; 95% CI: −0.68 ~ 3.87). The effects on insomnia were large and significant (g = 1.38; 95% CI: 0.38 ~ 2.38), but were no longer significant after adjustment for publication bias in any of the three methods and in the subsample of studies with low risk of bias (g = 0.95; 95% CI: −0.66 ~ 2.56). The effects on substance use problems were small (g = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.01 ~ 0.50), but just significant. They remained significant, however, in all three analyses in which the results were adjusted for publication bias, the effects were actually larger in all three analyses (g’s ranging from 0.39 to 0.56), and when limiting the analyses to studies with low risk of bias (g = 0.33; 95% CI: 0.11 ~ 0.56). The subgroup analyses did not result in significant differences between subgroups.

Effects of interventions in other comorbidities

gives the effects of trials in people with depression and comorbid conditions other than anxiety, insomnia and substance use problems. The figure separately gives the effects on depression and the comorbid mental health problems. Because of the differences between conditions, we did not pool the effect sizes. Several individual studies reported significant effects on depression (Bellino et al., Citation2006; Sinniah et al., Citation2017; Vitriol et al., Citation2009). Two studies also reported significant effects on the comorbid mental health problems (Sinniah et al., Citation2017; on suicide and Talbot et al., Citation2011 on PTSD). Unfortunately, not all studies reported a clear outcome on the comorbid mental health condition.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials examining the effects of psychotherapies in patients with depression and another comorbid mental disorder compared to no treatment. We included a total of 35 trials. Most trials focused on comorbid anxiety, insomnia or substance use problems and most were based on CBT (66% of the examined interventions). Overall, the studies had a significant and substantial effect on depression. When we examined each of the comorbidities separately, we found significant effects on depression in the trials recruiting participants from each of the three groups of comorbidities (anxiety, insomnia, substance use problems). In these three groups of studies, we also found significant effects on symptoms of anxiety, insomnia and substance problems.

Although we found significant effects on depression for all three major comorbidities, most of these effects were no longer significant after adjustment for publication bias and when only studies with low risk of bias were analysed. The same was true for the effects of psychotherapy on anxiety symptoms (in those with comorbid anxiety) and symptoms of insomnia (in comorbid insomnia). This means that the effects were highly uncertain and we should be careful with concluded too easily that treatments for depression with each of these comorbid disorders are effective. More, high-quality research is needed to further establish that.

In comorbid substance use problems, the effects on depression and on substance use problems were significant but small. On the one hand, that is good news, because the treatments seem to have some effects on both depression and substance use. On the other hand, the effects seem to be much smaller than in psychotherapy for depression in general, and in several sensitivity analyses the effects were no longer significant. That is worrying because the proportion of patients with comorbid depression and substance use problems is high (Herrman et al., Citation2022), also in primary care (Kotiaho et al., Citation2019) and in specialized care settings (Lamers et al., Citation2011). Clinicians should be aware of this and take this into consideration when offering treatments.

Because of the high comorbidity between depression and substance use, it can be expected that many of these patients are included in trials on psychotherapy for depression in general. It can also be expected, therefore, that the effects of therapies are larger than what is found in meta-analyses in patients without comorbid disorders. This is an important question for future research.

Given the high prevalence of comorbid conditions in depressive disorders, it is surprising that we found only such a relatively small number of trials examining therapies for these conditions. Among more than 400 trials comparing psychotherapies for depression to control conditions in our database, there were only 35 that focused on depression with other comorbid mental disorders. From a clinical perspective it is very important to examine the effects of psychotherapies (and other treatments) in comorbid conditions. Especially in specialized mental health care where more severe cases are treated, the proportion of depressed patients with another comorbid mental disorder is more the rule than the exception. It is important that future studies examine better whether treatments should first focus on depression, the comorbid condition, or both at the same time.

This review also shows that there is some uncertainty whether these therapies for depression are effective in these cases. It is therefore very important that more research on treatments of depression with other comorbid mental disorders is conducted. It is not only important to examine the effects of psychotherapies for depression with comorbid anxiety, insomnia, and substance use problems, but also other comorbidities. We found only a handful of studies examining the effects in cases with comorbid borderline personality disorders, PTSD, psychotic disorders, and OCD. No studies were found for, for example, eating disorders, or specific anxiety disorders.

This study has several important strengths. We conducted rigorous searches to identify relevant studies, we conducted state-of-the-art meta-analyses and conducted several sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of our findings. However, this meta-analysis also has several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. One important limitation is that the number of trials was small, and power was low in all analyses and even more so in the subgroup analyses we conducted. Furthermore, the unexplained heterogeneity in the pooled effect sizes was high across most analyses. This heterogeneity can be related to the considerable differences between studies in terms of diagnostic status (established through a diagnostic interview or through a self-report measure), the differences in control conditions, the exact contact of usual care, the recruitment methods and intervention characteristics such as format or number of sessions. Because of the small number of trials and low power, we were not able to examine the impact of these factors on the level of heterogeneity.

Another important limitation is the even smaller number of studies with low risk of bias. This makes the findings even more uncertain. We did not examine longer-term outcomes, but because of the small number of included studies, we believe that little knowledge about these long-term effects can be generated with the current set of studies.

We can cautiously conclude that psychotherapies for depression with comorbid anxiety, insomnia and substance use problems may have significant effects on depression and each of the three comorbid conditions, although this is uncertain because of several biases and the small number of included studies. The effects are large in comorbid anxiety and insomnia, but small in substance use problems. More research is very much needed in this clinically highly relevant field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The dataset that was used in this study is a subsample of the the larger dataset available at www.metapsy.org. The specific dataset is available through the first author of this paper.

References

- Ahmadpanah, M., Akbari, T., Akhondi, A., Haghighi, M., Jahangard, L., Bahmani, D. S., Bajoghli, H., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Brand, S. (2017). Detached mindfulness reduced both depression and anxiety in elderly women with major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Research, 257, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.030

- Baker, A. L., Kavanagh, D. J., Kay Lambkin, F. J., Hunt, S. A., Lewin, T. J., Carr, V. J., & Connolly, J. (2010). Randomized controlled trial of cognitiveâ? Behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: Short-term outcome. Addiction, 105(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02757.x

- Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G., & Schwarzer, G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22(4), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

- Baumgartner, C., Schaub, M. P., Wenger, A., Malischnig, D., Augsburger, M., Lehr, D., Blankers, M., Ebert, D. D., & Haug, S. (2021). “Take care of you” – Efficacy of integrated, minimal-guidance, internet-based self-help for reducing co-occurring alcohol misuse and depression symptoms in adults: Results of a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 225, 108806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108806

- Beatson, J. A., & Rao, S. (2013). Depression and borderline personality disorder. Medical Journal of Australia, 199, S24–S27. https://doi.org/10.5694/mjao12.10474

- Bellino, S., Zizza, M., Rinaldi, C., & Bogetto, F. (2006). Combined treatment of major depression in patients with borderline personality disorder: A comparison with pharmacotherapy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51(7), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370605100707

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley.

- Borenstein, M., Higgins, J. P. T., Hedges, L. V., & Rothstein, H. R. (2017). Basics of meta-analysis: I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Research Synthesis Methods, 8(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1230

- Brown, R. A., Ramsey, S. E., Kahler, C. W., Palm, K. M., Monti, P. M., Abrams, D., Dubreuil, M., Gordon, A., & Miller, I. W. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression versus relaxation training for alcohol-dependent individuals with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(2), 286–296. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2011.72.286

- Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Kuchibhatla, M., Lachowski, A. M., Bogouslavsky, O., Krystal, A. D., & Shapiro, C. M. (2017). Cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy for those with insomnia and depression: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Sleep, 40(4), zsx019. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx019

- Carpenter, K. M., Smith, J. L., Aharonovich, E., & Nunes, E. V. (2008). Developing therapies for depression in drug dependence: Results of a stage 1 therapy study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 34(5), 642–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990802308171

- Carter, E. C., Schönbrodt, F. D., Gervais, W. M., & Hilgard, J. (2019). Correcting for bias in psychology: A comparison of meta-analytic methods. Advances in Methods and Practice in Psychological Science, 2(2), 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847196

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., Leucht, S., Ruhe, H. G., Turner, E. H., Higgins, J. P. T., Egger, M., Takeshima, N., Hayasaka, Y., Imai, H., Shinohara, K., Tajika, A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Geddes, J. R. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10128), 1357–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7

- Cuijpers, P. (2017). Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: An overview of a series of meta-analyses. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne, 58(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000096

- Cuijpers, P. (2021). Psychological treatment of depression with other comorbid mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/37NUX

- Cuijpers, P., de Beurs, D. P., van Spijker, B. A. J., Berking, M., Andersson, G., & Kerkhof, A. J. F. M. (2013). The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression on suicidality and hopelessness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 144(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.025

- Cuijpers, P., & Karyotaki, E. (2020). A meta-analytic database of randomised trials on psychotherapies for depression. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/825C6.

- Cuijpers, P., Noma, H., Karyotaki, E., Cipriani, A., & Furukawa, T. (2019). Individual, group, telephone, self-help and internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for adult depression; a network meta-analysis of delivery methods. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(7), 700–707. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0268

- Cuijpers, P., Noma, H., Karyotaki, E., Vinkers, C. H., Cipriani, A., & Furukawa, T. A. (2020). A network meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression. World Psychiatry, 19(1), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20701

- Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Noma, H., Ciharova, M., Miguel, C., Karyotaki, E., Cipriani, A., Cristea, I., & Furukawa, T. A. (2021). Psychotherapies for depression: A network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry, 20(2), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20860

- Demyttenaere, K., Bruffaerts, R., Posada-Villa, J., Gasquet, I., Kovess, V., Lepine, J. P., Angermeyer, Matthias C., Bernert, S., de Girolamo, G., Morosini, P., Polidori, G., Kikkawa, T., Kawakami, N., Ono, Y., Takeshima, T., Uda, H., Karam, E. G., Fayyad, J. A., Karam, A. N. , and Chatterji, S. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health surveys. JAMA, 291(21), 2581–2590. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.21.2581

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

- Furukawa, T. A., Cipriani, A., Barbui, C., Brambilla, P., & Watanabe, N. (2005). Imputing response rates from means and standard deviations in meta-analyses. International Clinical international Clinical Psychopharmacologyogy, 20(1), 49–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200501000-00010

- Gaudiano, B. A., Busch, A. M., Wenze, S. J., Nowlan, K., Epstein-Lubow, G., & Miller, I. W. (2015). Acceptance-based behavior therapy for depression with psychosis: Results from a pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 21(5), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRA.0000000000000092

- Gumley, A., White, R., Briggs, A., Ford, I., Barry, S., & Stewart, C., Beedie, S., McTaggart, J., Clarke, C., MacLeod, R., Lidstone, E. (2017). A parallel group randomised open blinded evaluation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for depression after psychosis: Pilot trial outcomes (ADAPT). Schizophrenia Research, 183, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.11.026

- Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A., & Ebert, D. D. (2022). Doing meta-analysis with R: A hands-on guide. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press.

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press.

- Herrman, H., Patel, V., Kieling, C., Berk, M., Buchweitz, C., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Kohrt, B. A., Maj, M., McGorry, P., Reynolds, C. F., Weissman, M. M., Chibanda, D., Dowrick, C., Howard, L. M., Hoven, C. W., Knapp, M., Mayberg, H. S. , and Wolpert, M. (2022). Time for united action on depression: A lancet–world psychiatric Association Commission. The Lancet, 399(10328), 957–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02141-3

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Juni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Savovic, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, L., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2011). The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. The BMJ, 343(oct18 2), d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. The BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Hou, Y., Hu, P., Zhang, Y., Lu, Q., Wang, D., Yin, L., Chen, Y., & Zou, X. (2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy in combination with systemic family therapy improves mild to moderate postpartum depression. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 36(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1170

- Hunter, S. B., Watkins, K. E., Hepner, K. A., Paddock, S. M., Ewing, B. A., Osilla, K. C., & Perry, S. (2012). Treating depression and substance use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 43(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.004

- Johnson, J. E., & Zlotnick, C. (2012). Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(9), 1174–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.007

- Karyotaki, E., Efthimiou, O., Miguel, C., Maas Genannt Bermpohl, F., Furukawa, T. A., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., Patel, V., Mira, A., Gemmil, A. W., Yeung, A. S., Lange, A., Williams, A. D., Mackinnon, A., Geraedts, A., van Straten, A., Meyer, B., Björkelund, C., Knaevelsrud, C. … The Individual Patient Data Meta-Analyses for Depression (IPDMA-DE) Collaboration. (2021). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression; an individual patient data network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(4), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4364

- Karyotaki, E., Riper, H., Twisk, J., Hoogendoorn, A., Kleiboer, A., Mira, A., Mackinnon, A., Meyer, B., Botella, C., Littlewood, E., Andersson, G., Christensen, H., Klein, J. P., Schröder, J., Bretón-López, J., Scheider, J., Griffiths, K., Farrer, L., Huibers, M. J. H. , and Cuijpers, P. (2017). Efficacy of self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT) in treatment of depressive symptoms: An individual participant data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0044

- Kay Lambkin, F. J., Baker, A. L., Lewin, T. J., & Carr, V. J. (2009). Computer-based psychological treatment for comorbid depression and problematic alcohol and/or cannabis use: A randomized controlled trial of clinical efficacy. Addiction, 104(3), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02444.x

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

- Kotiaho, S., Korniloff, K., Vanhala, M., Kautiainen, H., Koponen, H., Ahonen, T., & Mäntyselkä, P. (2019). Psychiatric diagnosis in primary care patients with increased depressive symptoms. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 73(3), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2019.1584240

- Lamers, F., van Oppen, P., Comijs, H. C., Smit, J. H., Spinhoven, P., van Balkom, A. J. L. M., Nolen, W. A., Zitman, F. G., Beekman, A. T. F., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2011). Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(3), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu

- Lemma, A., & Fonagy, P. (2013). Feasibility study of a psychodynamic online group intervention for depression. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 30(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033239

- Liang, L., Feng, L., Zheng, X., Wu, Y., Zhang, C., & Li, J. (2021). Effect of dialectical behavior group therapy on the anxiety and depression of medical students under the normalization of epidemic prevention and control for the COVID-19 epidemic: A randomized study. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(10), 10591–10599. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2466

- Mahmoodi, M., Bakhtiyari, M., Masjedi Arani, A., Mohammadi, A., & Saberi Isfeedvajani, M. (2021). The comparison between CBT focused on perfectionism and CBT focused on emotion regulation for individuals with depression and anxiety disorders and dysfunctional perfectionism: A randomized controlled trial. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 49(4), 454–471. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000909

- Maina, G., Rosso, G., Rigardetto, S., Chiado Piat, S., & Bogetto, F. (2010). No effect of adding brief dynamic therapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with concurrent major depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 79(5), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1159/000318296

- Manber, R., Buysse, D. J., Edinger, J., Krystal, A., Luther, J. F., Wisniewski, S. R., Trockel, M., Kraemer, H. C., & Thase, M. E. (2016). Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy in patients with comorbid depression and insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(10), e1316–1323. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m10244

- McShane, B. B., Böckenholt, U., & Hansen, K. T. (2016). Adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis: An evaluation of selection methods and some cautionary notes. Perspectives in Psycholical Science, 11(5), 730–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616662243

- Miguel, C., Karyotaki, E., Ciharova, M., Cristea, I. A., Penninx, B., & Cuijpers, P. (2021). Psychotherapy for comorbid depression and somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 1–11, in press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004414

- Misri, S., Reebye, P., Corral, M., & Milis, L. (2004). The use of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(9), 1236–1241. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v65n0913

- Newby, J. M., Mackenzie, A., Williams, A. D., McIntyre, K., Watts, S., Wong, N., & Andrews, G. (2013). Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for mixed anxiety and depression: A randomized controlled trial and evidence of effectiveness in primary care [Wellbeing 6]. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2635–2648. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713000111

- Norell-Clarke, A., Jansson-Fröjmark, M., Tillfors, M., Holländare, F., & Engström, I. (2015). Group cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: Effects on sleep and depressive symptomatology in a sample with comorbidity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.09.005

- Pigeon, W. R., Funderburk, J., Bishop, T. M., & Crean, H. F. (2017). Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia delivered to depressed veterans receiving primary care services: A pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 217, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.003

- Rücker, G., Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R., Binder, H., & Schumacher, M. (2011). Treatment-effect estimates adjusted for small-study effects via a limit meta-analysis. Biostatistics, 12(1), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxq046

- Russell, A., Gaunt, D. M., Cooper, K., Barton, S., Horwood, J., Kessler, D., Metcalfe, C., Ensum, I., Ingham, B., Parr, J. R., Rai, D., & Wiles, N. (2020). The feasibility of low-intensity psychological therapy for depression co-occurring with autism in adults: The Autism Depression Trial (ADEPT) – a pilot randomised controlled trial. Autism, 24(6), 1360–1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319889272

- Rytwinski, N. K., Scur, M. D., Feeny, N. C., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2013). The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21814

- Sadler, P., McLaren, S., Klein, B., Harvey, J., & Jenkins, M. (2018). Cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with insomnia and depression: A randomized controlled trial in community mental health services. Sleep, 41(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy104

- Satre, D. D., Delucchi, K., Lichtmacher, J., Sterling, S. A., & Weisner, C. (2013). Motivational interviewing to reduce hazardous drinking and drug use among depression patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(3), 323–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.008

- Scogin, F., Lichstein, K., DiNapoli, E. A., Woosley, J., Thomas, S. J., LaRocca, M. A., Byers, H. D., Mieskowski, L., Parker, C. P., Yang, X., Parton, J., McFadden, A., & Geyer, J. D. (2018). Effects of integrated telehealth-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression and insomnia in rural older adults. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(3), 292‐309. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000121

- Sinniah, A., Oei, T., Maniam, T., & Subramaniam, P. (2017). Positive effects of individual cognitive behavior therapy for patients with unipolar mood disorders with suicidal ideation in Malaysia: A randomised controlled trial. Psychiatry Research, 254, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.026

- Staner, L. (2010). Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.09.003

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., & Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H. Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. The BMJ, 366, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Talbot, N. L., Chaudron, L. H., Ward, E. A., Duberstein, P. R., Conwell, Y., O’Hara, M. W., Tu, X., Lu, N., He, H., & Stuart, S. (2011). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed women with sexual abuse histories. Psychiatric Services, 62(4), 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.4.pss6204_0374

- van der Zweerde, T., van Straten, A., Effting, M., Kyle, S. D., & Lancee, J. (2019). Does online insomnia treatment reduce depressive symptoms? A randomized controlled trial in individuals with both insomnia and depressive symptoms. Psychological Medicine, 49(3), 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001149

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03

- Vitriol, V. G., Ballesteros, S. T., Florenzano, R. U., Weil, K. P., & Benadof, D. F. (2009). Evaluation of an outpatient intervention for women with severe depression and a history of childhood trauma. Psychiatric Services, 60(7), 936–942. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.7.936

- Wagley, J. N., Rybarczyk, B., Nay, W. T., Danish, S., & Lund, H. G. (2013). Effectiveness of abbreviated CBT for insomnia in psychiatric outpatients: Sleep and depression outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(10), 1043–1055. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21927

- Wanders, R. B., van Loo, H. M., Vermunt, J. K., Meijer, R. R., Hartman, C. A., Schoevers, R. A., Wardenaar, K. J., & de Jonge, P. (2016). Casting wider nets for anxiety and depression: Disability-driven cross-diagnostic subtypes in a large cohort. Psychological Medicine, 46(16), 3371–3382. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002221

- Watanabe, N., Furukawa, T. A., Shimodera, S., Morokuma, I., Katsuki, F., Fujita, H., Sasaki, M., Kawamura, C., & Perlis, M. L. (2011). Brief behavioral therapy for refractory insomnia in residual depression: An assessor-blind, randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(12), 1651–1658. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06130gry

- Weitz, E., Kleiboer, A., van Straten, A., & Cuijpers, P. (2018). The effects of psychotherapy for depression on anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48(13), 2140–2152. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003622

- Wuthrich, V. M., & Rapee, R. M. (2013). Randomised controlled trial of group cognitive behavioural therapy for comorbid anxiety and depression in older adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(12), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.09.002

- Wuthrich, V. M., Rapee, R. M., Kangas, M., & Perini, S. (2016). Randomized controlled trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy compared to a discussion group for co-morbid anxiety and depression in older adults. Psychological Medicine, 46(4), 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002251

- Ye, Y. Y., Zhang, Y. F., Chen, J., Liu, J., Li, X. J., Liu, Y. Z., Lang, Y., Lin, L., Yang, X. -J., & Jiang, X. -J. (2015). Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (ICBT-i) improves comorbid anxiety and depression—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 10(11), e0142258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142258

- Zemestani, M., & Fazeli Nikoo, Z. (2019). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for comorbid depression and anxiety in pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(2), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00962-8