ABSTRACT

Background: The Syrian conflict has resulted in major humanitarian crises. The risk is particularly high amongst female children who face additional gendered risks, such as harassment and sexual violence, including a rise in prevalence of child marriage. Despite the importance of this topic, current literature remains relatively scarce.

Objectives: This study aims to explore the social and healthcare repercussions of Syrian refugee child marriages in Jordan and Lebanon.

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was carried out to gather evidence, from a total of eight articles. Data analysis was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme check tool to systematically assess the trustworthiness, relevance and results of the included papers.

Results: The findings of this research identify tradition, honour, economics, fear, and protection-related factors as drivers of child marriage of refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. These motives overlap with findings regarding access to reproductive health and reproductive rights. The lack of autonomy of the child to give informed consent is augmented in the context of protracted violence and displacement.

Conclusion: There is a need for a holistic approach to provide safe spaces, education, and protection to young girls and their families to reduce their acceptance of child marriage.

Responsible Editor

Maria Emmelin, Umeå University, Sweden

Background

Findings show that the number of Syrian refugees fleeing to other countries continues to rise [1]. As of July 2018, there were 668,123 registered Syrian refugees in Jordan and 976,000 refugees in Lebanon [Citation2,Citation3], indicating that the highest density of the Syrian refugee population is in these countries. A common challenge in conflict regions is the rise in the presence of child marriage rates, for various reasons [Citation4]. Svanemyr et al. [Citation5] conclude that even though child marriage is not widespread in the contemporary Arab region, there has been a rise in its presence in recent years due to the nature of conflicts and the need for protection. Prior to the crisis in Syria, child marriage took place amongst 13% of girls under the age of 18, but since then, forced displacement has led to a major increase in this number [Citation6]. The United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) now reports that 35% of Syrian refugee girls are married before the age of 18 [Citation7].

Lack of official marriage registration makes it difficult to obtain valid information about the prevalence of child marriage, as many do not have the documentation required to complete some of the initial registration steps. For instance, in Lebanon, Syrian refugees face a number of challenges when registering births and marriages, limiting their access to services such as shelter and education [Citation6]. Many Syrian refugees do not have valid residency and many parents do not have valid proof of marriage, which is required to complete some of the initial birth registration steps such as obtaining a birth certificate [Citation6].

This potential rise in child marriages may be linked to the fragility characterising these refugees’ life situation. Marrying a girl at a young age may be perceived as increasing the security of the girl and/or her family [Citation8]. A qualitative study exploring child marriage practices found that protection, security and financial hardships were the most common motives for child marriage [Citation7]. In their assessment of female refugees from Syria, UNICEF found that many girls view early marriage as an opportunity to escape poverty and workforce exclusion [Citation9].

According to DeJong et al. [Citation10], various approaches to defining child marriage have been adopted. While most studies define child marriage as a marriage in which one or both parties are married before the age of 18 [Citation11], others contend that informed consent should be a part of the marriage union, and that this is lacking in child marriage. UNICEF [Citation12] concludes child marriages are those where one or both parties are underage and have not personally expressed full, free and informed consent to the union. This review study adopts this holistic definition, where a focus on age is not the only factor, but consent of the individual is also taken into account.

Child marriage can be linked to a range of poor social and health outcomes for women and girls, including high risks of early pregnancy [Citation13], mental health issues due to forced early sexual debut [Citation14], and maternal death and disability, including post-pregnancy complications [Citation15]. Additional sexual health challenges, such as the lack of agency of brides to negotiate the use of condoms even in conditions of high risk of HIV infection, are reported [Citation16]. Such challenges are associated with the potential presence of increasing risk of domestic violence and power differentials in the relationship, which could be attributed to differences in age. There is evidence which shows that early marriage is linked to negative social outcomes, including school dropout, lack of employment and low educational attainment [Citation15,Citation16].

Prior evidence has shown that while child marriage during conflict and displacement is not unique [Citation11], the nature of outcomes and the reasons for such practices are found to be varied based on contextual differences [Citation17]. The rise in child marriage amongst Syrian refugees has been studied previously for a range of reasons, including understanding underlying motives and determining the extent and prevalence of such forced marriages [Citation18,Citation19]. Given potential variations in the implications of child marriage by region, it is essential that specific objectives on outcomes and antecedents of child marriage are identified.

The primary aim of this review is to present a holistic analysis of the reasons behind child marriage amongst Syrian refugees. Secondarily, this review aims to explore the refugee populations’ access to autonomous decision-making regarding health and family planning in Lebanon and Jordan. Thus, the major focus of this review is to determine the motives which support female child marriage among Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon and to assess reproductive decision-making, including access to contraceptive use, by Syrian child bride refugees in Jordan and Lebanon.

Methods

As Clark and Oxman [Citation20] argue, the search boundaries for an investigation need to be set to conduct a comprehensive systematic review of literature. The review process used here, which included an ongoing discussion between the two authors, adopted the PICO model (patient/problem, intervention/exposure, comparison and outcome; see ) to evaluate the research objectives [Citation21]. The use of the PICO model helped streamline the search process to maximise the likelihood of finding relevant articles.

Table 1. PICO framework and search terms.

This study adopted a systematic literature review methodology. The search terminologies identified in were used to search different journals and online databases, including PubMed, ScienceDirect, CINAHL and EBSCO. Raj et al. [Citation22] contend that there is a gap in health-related outcome reporting amongst refugee communities; Therefore, this study adopted a grey literature approach to identify additional articles. Grey literature and reports published by international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were included, with a focus on Save the Children (STC), the United Nations and other relief organisations. Once the search terminology and search database were established, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined. The key inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed below.

Inclusion criteria

Studies discussing child marriage amongst refugees in Jordan and Lebanon.

Clear description of reasons/motives or reproductive rights/decisions.

Reference to challenges of refugees.

Peer-reviewed or reports from International NGOs.

Exclusion criteria

Previously published meta-analyses or systematic reviews on the same subject.

Non-English articles.

Research published before 2012.

Fink [Citation23] contends that the basic guideline for approval can be determined using the method of quality evaluation. Quality assessment requires following the right approach to identify corroborative evidence. According to Cochrane [Citation24], the method of quality estimation should cluster and categorise articles on the basis of quality and arrangement. This research adopts the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) guidelines to address the quality of the studies chosen to address methodological rigour assessment [Citation25]. Use of the CASP tool can help provide a complex assessment of study evidence which can contribute to acceptance or rejection of the studies under question. presents the findings of the CASP analysis.

Table 2. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), Save The Children (STC) Focus group discussion (FGD).

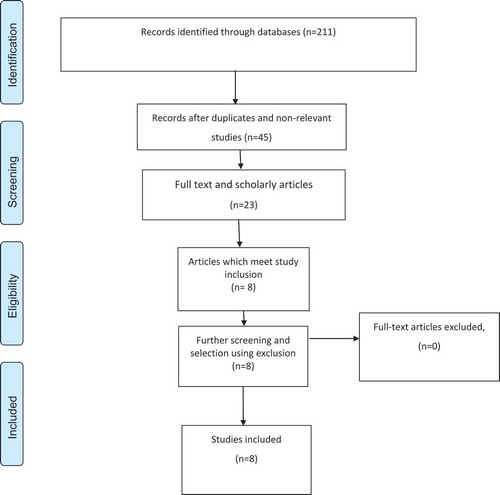

From the above CASP analysis, it is evident that while most articles have some challenges with their methodological rigour, they provide clarity in aim, choice of method, analysis and findings. It was concluded that despite the methodological challenges, these articles should be chosen for the review given their ability to provide insights and evidence on the proposed research objectives. presents an assessment of the PRISMA framework.

Results

A thematic approach was used to identify key themes. Each study was examined for relevant themes that could answer the research objectives. The following summarises the findings with a summary of the themes. The total number of articles included in this review was eight. Most of the studies examined were qualitative, cross-sectional [Citation6,Citation26,Citation27] or narrative reviews [Citation28–Citation30]. There were two studies that adopted a mixed-methods approach, collecting both qualitative and quantitative data [Citation31,Citation32]. Of the eight studies discussed, five related to the motives behind child marriage [Citation6,Citation28,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32]. Three studies focused predominantly on reproductive rights-related challenges including access to contraceptives and their use [Citation26,Citation27,Citation30]. Three studies were based in Lebanon [Citation6,Citation27,Citation31] and five in Jordan [Citation26,Citation28–Citation30,Citation32]. The key themes identified with respect to motivation for child marriage ranged from protection (physical or economic) to tradition and protection of honour.

Motives for child marriage amongst Syrian refugee communities in Jordan and Lebanon

Physical protection

The lack of male support was reported by many self-identified child brides as a potential reason for child marriage. Bartels et al. [Citation31], who focused on Syrian girls in Lebanon, found that physical harassment in camps, as well as sexual advances made by men and guards against younger children, are some of the key reasons why parents pressure their children to get married. Mourtada et al. [Citation6] concluded that child brides from Syria often face greater challenges with respect to sexual harassment, as they are rarely given the opportunity to make formal complaints. Gaining a male protector through marriage is often considered an ideal approach to overcoming potential attacks from unknown individuals. STC [Citation28] indicate that given the rise in the number of casualties of the ongoing war, there are many families with a limited number of men in the household. The perception of such men being unable to provide sufficient physical protection for women and girls in their family encourages the acceptance of early marriage as a trend. In a United Nations (UN) Women Report [Citation32], the findings on reasons for early marriage among men and women showed that marriage is a form of protection for girls (28.7%) in the community. Therefore, the perception that child marriage can enhance the physical protection of the child seem to be a key motive which has led to the increase in child marriage.

Community expectations

Community expectations and worry associated with honour are another common motive highlighted across the chosen studies. In their study, Mourtada et al. [Citation6] reported that interview participants acknowledged their unwillingness to support child marriage but were often forced to do so by community trends. The interview participants highlighted the concept of al Sutrah, which indicates a desire to protect the honour of their women. Adolescent women’s reputations are a cornerstone of familial reputation, and a rise in physical harassment has led to community-level adaptations to child marriage. Thus, many families look to child marriage to reduce the risk of physical harm to their female children through early marriage. Bartels et al. [Citation31] contend that many men consider child marriage in Lebanon to be a way of protecting children from rape and the threat of sexual violence. Girls exposed to different forms of sexual abuse and harassment may find it difficult to marry later due to societal shunning, resulting in the rise in acceptance of the practice [Citation31].

The STC [Citation28] report supports this notion and concludes that familial honour protection is a key driver in supporting acceptance of child marriage at the societal level amongst Syrian refugees in Jordan. Based on a quantitative survey, the UN Women Report [Citation32] also concluded that the most common reason for early marriage given by women and men was to protect family honour (women: 39.3%) and as a part of custom and tradition (women: 44.2%; men: 33.4%).

Acosta and Thomas [Citation29] reported that many Syrian refugees in countries like Lebanon and Jordan are raped and then forced to marry. Bartels et al. [Citation31] also contend that single women are forced to marry off their daughters due to rape and/or threats. Associated challenges of being shunned by society may hasten parents’ decision to allow their daughters to marry sexual offenders [Citation31].

Financial needs/economic reasons

Economic challenges and hardship are often listed as key motives influencing decisions on forced early marriage. Bartels et al. [Citation31] concluded that the perceived lack of protection often relates to financial access, as young girls have limited resources to support themselves. Since these girls are forced to move to Lebanon due to the conflict, they have limited schooling and educational opportunities, providing them with only low-skilled employment options [Citation31]. If they receive marriage propositions from well-settled men, they may choose this option out of desperation [Citation31]. Mourtada et al. [Citation6] also concluded that conflict and displacement result in major challenges to refugee family operations, and participants in focus group discussions reported dire living conditions, poverty and insecurity, which act as potential motivators. Given that household finances are dire and likely to become worse, marrying off a daughter at an early age can help reduce the overall financial burden on the family.

Acosta and Thomas [Citation29], in their assessment of the refugee communities, concluded that Syrian families in Jordan and Lebanon face severe economic distress. Since most of them depend on family savings, and given that work is hard to find, it may be difficult to support the entire family. In this context, mothers believe that marrying off children is essential as it improves the child bride’s access to better economic opportunities. The UN Women Report [Citation32] indicates that economic reasons for marrying at a young age include access to housing for women (20.1%) and providing options to alleviate financial problems (28.4%).

Parental support and family decisions

While many studies discussed families’ individual decisions to support child marriage for the purposes of poverty alleviation or overall family support, some studies identified pressure on young girls to fulfil family expectations and ease their overall decision-making. For instance, Mourtada et al. [Citation6] concluded that since there was rising fear of potentially unfavourable gossip from local communities due to rumours of social misconduct, many women chose to get married to reduce the overall burden on their family. The STC [Citation28] report also found that young girls recognise the lack of opportunities for education and employment and are willing to get married at an early age to reduce poverty challenges faced by their family. El-Mowafi et al. [Citation26] concluded that there are often limited choices available to young brides as families abdicate responsibility, which leads to their decision to accept marriage.

Reproductive rights challenges

The second key objective of this research was to assess health outcomes with specific reference to a child bride’s contraceptive needs as well as her knowledge about, access to, and use of contraceptives.

Lack of acceptance

Cherri et al. [Citation27] and Sahbani et al. [Citation30] found that there is limited acceptance regarding the use of contraceptives. The authors argue that many girls have to obtain permission from their husbands, which may not be given. El-Mowafi et al. [Citation26] concluded that requesting access to contraceptive use can create additional challenges of physical violence. Sahbani et al. [Citation30] argue that the husband’s refusal prevents married girls from using contraception and, given their lack of agency, child brides are forced to comply with their husband’s wishes. Amongst married women with no children, the use of birth control can be difficult, as they are under societal pressure or religious pressure not to use it [Citation30].

Knowledge of contraception is low

According to Sahbani et al. [Citation30], there are differences in knowledge about and attitudes towards contraceptive use. While there is a certain level of acceptance that contraceptive use can prevent unforeseen health consequences, including sexually transmitted diseases, this knowledge is low. However, there is some awareness of its use and its impact on pregnancy prevention. Sahbani et al. [Citation30] also concluded that young girls are rarely given a choice about getting married and that the choice of contraceptive use is also limited. The authors further suggest that challenges linked to a lack of access to education on healthcare options and the constant pressure to get pregnant due to societal norms further reduce the option of transmitting knowledge and information about contraceptives and their use [Citation30].

Access to contraception is low

Despite varying levels of knowledge on modes of contraceptive use, the most important barrier is the lack of access to such contraceptives. Sahbani et al. [Citation30] concluded that on top of the pressure to marry, many girls are forced to procreate and have children, which is a primary objective of the husband in their family. Given this acceptance at the community level, most girls are unaware of international aid-driven efforts to increase access to contraceptive use. Cherri et al. [Citation27] contend that even if there is access to contraceptives, there are challenges of cost. These authors concluded that low-quality intrauterine devices (IUDs) were not effective, and those which were of good quality were highly priced. Many women were unaware that IUDs were given for free in primary healthcare centres.

Discussion

The findings of this review show that there are several motives which drive child marriage decisions; some are unique to the Middle Eastern context, including family honour, societal norms and supporting family decisions, and some are linked to financial challenges and burden, physical assault and safety-related challenges. Some of the challenges regarding reproductive rights relate to the lack of acceptance of, knowledge about, and access to contraceptives. A common theme that most of the studies in this systematic review identify is that there is a potential change in marriage practices amongst refugee communities [Citation6,Citation28,Citation31,Citation32]. Prior findings at a global level have shown similar motives, including concerns over safety, worsening economic conditions and a lack of future options for education or employment [Citation11].

Bedri et al. [Citation33] conclude that many families in Sudan believe in the notion of al Sutrah, or the social protection and preservation of the honour of the family through the honour of the bride. Evidence from refugee camps has shown a rise in concern about the safety of women; furthermore, there is increasing evidence of rape being used as a tool to control and terrorise families [Citation34]. Traditionally, most Arab societies consider the virginity of the bride a key element which symbolises her purity [Citation35]. To address the challenge of increasing insecurity and vulnerability, many families resort to early marriage to protect their daughters and promote their family honour. Family expectations and societal norms are also key themes which overlap with the lack of reproductive rights and agency of child brides. Evidence presented in this systematic review [Citation26,Citation27] has shown that women who express a desire to delay pregnancy may face the challenge of being abandoned by their husband. In many emergency contexts, families believe that they are protecting the girl’s honour when she is forced to marry or stay married to an individual. As Sahbani et al. [Citation30] rightly argue, marriage cannot guarantee child safety, with some women being abandoned after giving birth to children. Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) [Citation11] argue that implementation agencies and donors who fight against child marriage should be willing to discuss the motives behind early child marriage and its potential implications for long-term child wellbeing, including access to reproductive rights and reproductive health.

Different studies [Citation26,Citation31] conclude that the physical safety and wellbeing of young girls is often a common element associated with the motives behind child marriage. Many studies reviewed in this research conclude that worry over physical safety and protection from harassment remain primary reasons behind supporting child marriage [Citation26,Citation31]. Zawati [Citation34] further argues that in internal and transnational armed conflicts, rape continues to be an instrument of patriarchal domination and becomes a widespread weapon of terror and torture which rebels use to gain allegiance. The use of rape in refugee camps has been associated with intimidation and gaining favour. Interestingly, the family pressure and worry regarding physical threats is more evident than that experienced by the child brides themselves. Another key finding that should be discussed is the perception of protection. For example, Bartels et al. [Citation31] argue that though family members (especially men) view child marriage as protection against sexual harassment, many women view it as an overreaction. They believed that young girls were being protected too much and that girls were often perceived to be not protected enough. This supports evidence that calls for a better balance between family expectations and those of the child. Aid agencies that work in the region should consider giving practical support that can provide immediate resolution to such problems.

The impact of lack of education is also an underlying factor which creates challenges in regards to child marriage and continues to have implications for access to reproductive rights. Mourtada et al. [Citation6] conclude that there is a significant minimisation in the movement of women in Lebanese and Jordanian society, which reduces opportunities for education or employment. This makes them dependent on men, resulting in a lack of agency and the continued presence of patriarchal implications associated with child marriage. This lack of agency has been linked to transactional sex and short-term contractual marriages which leave child brides with children and in poverty. Bartels et al. [Citation31] identify that there are girls who are married for brief periods of time to multiple men for money paid to their families. The girls have no autonomy in their decision-making in regards to any aspect of their life. Kidman [Citation36] also concludes that such girls have limited access to contraceptive use and no knowledge about preventing pregnancy or potentially dangerous health challenges. Zuhur [Citation37] further indicates that this can lead to additional challenges of inadequate childbirth spacing, transmission of infection and HIV/AIDS risks. Any intervention that is targeted towards young girls in the context of being a refugee should address ways to improve the rights of such children, to legalise the age of consent and create strict enforcement laws surrounding their implementation.

The lack of education and rising dependence in the form of financial needs leads to a limited understanding of informed consent. An assessment of child marriage amongst such refugees shows a lack of knowledge and ability to give informed consent [Citation37]. A child bride is considered to be unable to consider the gravity and implications of sex and may be unable to consent to have sex [Citation37]. Similarly, the lack of autonomy associated with the use of contraceptives and the associated challenges of pregnancy [Citation38] can be attributed to the limited opportunity for consent. Many girls who agree to get married are misinformed about their choices [Citation38]. The suggestion by the community and the family that girls who are victims of protracted violence will be safer and their honour will be intact further contributes to misinformed brides [Citation38]. Such girls are often subjected to rising challenges of continued physical and emotional domestic violence, with a lack of empowerment regarding the use of contraceptives [Citation37]. This evidence supports the need for safe spaces within refugee centres which can serve as appropriate units for the introduction of life skills training, vocational training and, more importantly, better education on sexual and reproductive health.

Kidman [Citation36], in a global assessment of the challenges linked to programmatic interventions proposed to address child marriage amongst refugees, argues there is a need for context-specific assessment of child needs. For example, the findings provided by Bartels et al. [Citation31] and Mourtada et al. [Citation6] clearly highlight a mix of challenges, including honour-based issues and economic hardships. However, a UN [Citation32] study which focused on Jordan found that the most common factor associated with child marriage was supporting tradition and customs. These findings suggest the need to move beyond a one-size fits all approach and to implement context-specific plans which are customised to the needs of the region and the refugee support centre.

Globally, the UN has designated an internal panel for gender and development to convene and identify ways through which child marriage could be eradicated [Citation39]. However, the focus of the pilot project was on Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Ghana, Somalia and Zimbabwe [Citation39]. There are some limitations associated with this study which should be acknowledged. This systematic review focused on five peer-reviewed and three grey literature databases and included a relatively limited number of studies. Thus, the knowledge gained might be incomplete and important perspectives may be absent. Further, this review did not compare child marriage motives among non-refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, in which could have provided a more comprehensive picture of the motives of the refugee population in particular. Based on this review we recommend a comprehensive assessment of child marriage motives by comparing Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon with child marriage in other countries. This can help provide region-specific insight and help differentiate between country-specific challenges; tradition-specific challenges and specific challenges in the refugee population. Future research need to explore the differences of marriages carried out between children and those taking place between adult men and female children.

Conclusion

Child marriage can be a gateway to other forms of gender-based violence and can have lifelong adverse impact on the child and her offspring. This review has identified some common reasons associated with child marriage and factors that reduce the autonomy of child brides with respect to their reproductive rights. The key themes identified with respect to drivers for child marriage ranged from physical and economical protection, to tradition and safeguarding of female honour; augmented by the social context of protracted suppression, lack of autonomy, violence and fear.

Key issues that inhibits reproductive rights relates to constraints in regards to a lack of access to education, contraception and health care, limited knowledge, and a lack of agency. These findings suggest that policy makers and refugee agencies should establish safe spaces for would-be child brides, supporting the girls and parents’ willingness to speak out about sensitive issues, providing better family planning and contraceptive education.

Ethics and consent

Not applicable.

Paper context

This study adopted a systematic literature review methodology to discuss the reasons/motives and reproductive rights/decisions associated with child marriage amongst refugees in Jordan and Lebanon.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Joel Somerville for his efforts in proofreading this publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

R. El Arab

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- Lilleston P, Winograd L, Ahmed S, et al. Evaluation of a mobile approach to gender-based violence service delivery among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. In: Health policy and planning. 2018 Jun 13.

- UNHCR operational portal: refugee situations. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 13]. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/71

- Relief Web. Fact sheet: Jordan. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 11]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FactSheetJordanFebruary2018-FINAL_0.pdf

- Goldstein JS. War and gender. In: Encyclopedia of sex and gender. Boston, MA: Springer; 2003. p. 107–12.

- Svanemyr J, Chandra-Mouli V, Raj A, et al. Research priorities on ending child marriage and supporting married girls. Reprod Health. 2015 Dec;12:80.

- Mourtada R, Schlecht J, DeJong J. A qualitative study exploring child marriage practices among Syrian conflict-affected populations in Lebanon. Confl Health. 2017 Nov;11:27.

- UNFPA. New study finds child marriage rising among most vulnerable Syrian refugees [Internet]. UNFPA 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 08]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/news/new-study-finds-child-marriage-rising-among-most-vulnerable-syrian-refugees

- Jain S, Kurz K. New insights on preventing child marriage: A global analysis of factors and programs. International Center for Research on Women (ICRW); 2007.

- UNICEF. Empowering Syrian refugee women in Jordan: a proposal prepared for UNICEF next generation [Internet]. UNICEF 2017. [cited 2019 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.unicefusa.org/sites/default/files/170615%20NextGen%20Jordan%20Full%20proposal_0.pdf

- DeJong J, Sbeity F, Schlecht J, et al. Young lives disrupted: gender and well-being among adolescent Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl Health. 2017;11:23.

- CARE. “To protect her honour”. Child marriage in emergencies: the fatal confusion between protecting girls and sexual violence. 2015 [cited 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/59751

- UNICEF. A study on early marriage in Jordan 2014. [cited 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/files/UNICEFJordan_EarlyMarriageStudy2014-email.pdf

- Kamal SM, Hassan CH. Child marriage and its association with adverse reproductive outcomes for women in Bangladesh. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015 Mar;27:NP1492–506.

- Charles L, Denman K. Syrian and Palestinian Syrian refugees in Lebanon: the plight of women and children. J Int Women’s Stud. 2013 Dec 1;14:96.

- Lemmon GT, ElHarake LS. Child brides, global consequences: how to end child marriage. Council on Foreign Relations; 2014 Jul 1.

- Falb KL, Annan J, Kpebo D, et al. Differential impacts of an intimate partner violence prevention program based on child marriage status in rural Côte d’Ivoire. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Nov 1;57:553–558.

- Collins VE. State crime, women and gender. Routledge; 2015 Oct 5.

- Raj A, Boehmer U. Girl child marriage and its association with national rates of HIV, maternal health, and infant mortality across 97 countries. Violence against Women. 2013 Apr;19:536–551.

- Oleske D. Epidemiology and the delivery of health care services: methods and applications. Springer Science; Business Media; 2001.

- Clarke M, Oxman AD. Cochrane Library. Cochrane reviewers’ handbook. 2003. p. 420.

- Stone PW. Popping the (PICO) question in research and evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15:197–198.

- Raj A, Jackson E, Dunham S. Girl child marriage: a persistent global women’s health and human rights violation. In: Global perspectives on women’s sexual and reproductive health across the lifecourse. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 3–19.

- Fink A. Conducting research literature reviews: from the internet to paper. CA Sage; 2005.

- Cochrane. Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2012 [cited 2018 Aug 12]. Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org/

- Casp U CASP checklists. [cited 2018 Aug 26]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Systematic-Review-Checklist_2018.pdf

- El-Mowafi IM, Hammad M, Foster A. Child brides’ knowledge of and attitudes toward emergency contraception: a qualitative study with Syrian refugees in Jordan. Contraception. 2017 Oct 1;96:268.

- Cherri Z, Gil Cuesta J, Rodriguez-Llanes JM, et al. Early marriage and barriers to contraception among Syrian refugee women in Lebanon: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jul 25;14:836.

- Save the Children Report (STC). Too young to wed. The growing problem of child marriage among Syrian girls in Jordan. 2014 [cited 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/TOO_YOUNG_TO_WED_REPORT_0714_0.PDF

- Acousta and Thomas. Early/child marriage in Syrian refugee communities. 2014 [cited 2018 Aug 12]. Available from: nolostgeneration.org/sites/default/files/webform/contribute_a_resource_to_nlg/116/syrian-refugees-and-early-marriage.pdf

- Sahbani S, Al-Khateeb M, Hikmat R. Early marriage and pregnancy among Syrian adolescent girls in Jordan; do they have a choice? Pathog Glob Health. 2016 Sep;110:217.

- Bartels SA, Michael S, Roupetz S, et al. Making sense of child, early and forced marriage among Syrian refugee girls: a mixed methods study in Lebanon. BMJ Glob Health. 2018 Jan 1;3:e000509.

- UN women report, Gender-based violence and child protection among Syrian refugees in Jordan, with a focus on early marriage. 2013 [cited 2018 Aug 11]. Available from: http://jo.one.un.org/uploaded/publications_book/1458653027.pdf

- Bedri N, Elhussein T, Elsamani L, et al. Exploring stakeholders and activists’ perspectives on interventions for combating girl child marriage in Sudan. Ahfad J. 2016 Jun 1;33.

- Zawati H. Sectarian war in Syria introduced new gender-based crimes. World Post. 2016 [cited 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hilmi_Zawati/publication/294736943_Sectarian_War_in_Syria_Introduced_New_Gender-Based_Crimes/links/56c3aa8a08ae8a6fab5a1cf9.pdf

- Minces J. The house of obedience: women in Arab society. Palgrave Macmillan; 1982.

- Kidman R. Child marriage and intimate partner violence: a comparative study of 34 countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 Oct 12;46:662–675.

- Zuhur S Considerations of ‘honor’ crimes, FGM, kidnapping/rape, and early marriage in selected Arab nations. In Expert Paper prepared for the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on good practices in legislation to address harmful practices against Women. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2009 May.

- DeJong J, Jawad R, Mortagy I, et al. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in the Arab countries and Iran. Reprod Health Matters. 2005 Jan 1;13:49–59.

- Menz S. Statelessness and child marriage as intersectional phenomena: instability, inequality, and the role of the international community. Cal L Rev. 2016;104:497.