ABSTRACT

There is increasing global attention to the importance of menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) for the lives of those who menstruate and gender equality. Yet, the global development community, which focuses on issues ranging from gender to climate change to health, is overdue to draw attention to how addressing MHH may enable progress in attaining the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To address this gap, we undertook a collective exercise to hypothesize the linkages between MHH and the 17 SDGs, and to identify how MHH contributes to priority outcome measures within key sectoral areas of relevance to menstruating girls in low- and middle-income countries. These areas included Education, Gender, Health (Sexual and Reproductive Health; Psychosocial Wellbeing), and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH). These efforts were undertaken from February – March 2019 by global monitoring experts, together with select representatives from research institutions, non-governmental organizations, and governments (n = 26 measures task force members). Through this paper we highlight the findings of our activities. First, we outline the existing or potential linkages between MHH and all of the SDGs. Second, we report the identified priority outcomes related to MHH for key sectors to monitor. By identifying the potential contribution of MHH towards achieving the SDGs and highlighting the ways in which MHH can be monitored within these goals, we aim to advance recognition of the fundamental role of MHH in the development efforts of countries around the world.

Responsible Editor Stig Wall

Background

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a collective agenda that identifies how the global society can enable sustainable economic, social, and environmental development for all, with an emphasis in the preamble to the SDGs on the need ‘to achieve gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls [Citation1]. Despite the emphasis on gender, the SDGs do not explicitly address the natural biological occurrence of menstruation, something experienced by almost two billion people globally, or its effects on the health and development agenda [Citation1]. There is an overdue need to assess the importance of menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) towards enabling progress across the entirety of the 17 SDGs, and highlight the sectors that would benefit from addressing menstruation when seeking to achieve their own goal-specific outcomes [Citation2].

The onset of menstruation, menarche, is a natural and important aspect of a female’s physiological development [Citation3–5]. From menarche through to menopause, people who menstruate experience the necessity of regularly managing menstruation: collecting, removing, and cleaning menstrual blood from the body; contraceptives that may disrupt menstrual bleeding; and for some, the experience of debilitating menstrual discomfort or disorders, for which, awareness, diagnosis and treatment is still lacking. In most societies, menstruation is laden with societal taboos and secrecy, which can hinder the ability to manage menstruation with ease and confidence [Citation6]. Menarche may also bring expectations about roles, responsibilities, and behaviors, in some cases serving as a ‘signal’ of sexual or marital readiness [Citation7,Citation8] and intensifying the gendered experiences of girls, women, and all people who menstruate [Citation9,Citation10].

The term ‘menstrual health and hygiene (MHH)’ is used to describe the needs experienced by people who menstruate, including having safe and easy access to the information, supplies, and infrastructure needed to manage their periods with dignity and comfort (menstrual hygiene management) [Citation11] as well as the systemic factors that link menstruation with health, gender equality, empowerment, and beyond [Citation12].

We posit that to fully achieve the SDGs by 2030, it is necessary to recognize MHH as a contributing factor to a broad set of SDGs. In this paper, we outline the potential linkages between MHH and all of the SDGs. Furthermore, to ensure MHH is adequately considered, we highlight the range of outcomes to which unmet menstrual needs are relevant, as well as specific outcomes prioritized within sectors closely aligned with MHH, with a main focus on girls in and out of school from low- and middle-income countries.

A framework linking MHH with SDGs

In highlighting the relevance of MHH across a broad set of global priorities, we suggest that MHH may align with the SDGs in the following ways: (1) MHH directly contributes to achieving a given SDG, but its role has not been recognized or directly evaluated; (2) MHH contributes to achieving a given SDG through clear indirect pathways, suggesting a value to prioritizing attention; (3) MHH is influenced by progress towards a given SDG, and may serve as a ‘proxy’ for gender-equitable progress; and (4) potential but unclear relationship between SDG and MHH (see ).

Figure 1. Relationship between menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Linkages between the SDGs and MHH can be made evident by questioning how the overall achievement of a given SDG may be altered if MHH is not addressed. For example, in examining SDG3, which focuses on health, is it possible to achieve health and wellbeing for all if MHH practices, knowledge, access to healthcare, and support are not adequate or available? If not, the global community must consider the policy levers available to address this gap. Or, in examining SDG5, is it possible to achieve gender equality of schools, workplaces and even households if they do not provide social and physical environments enabling safe, hygienic, and comfortable management of menstruation? If not, governments must consider resource investments to address this need.

The overall aim of this paper is to raise awareness of MHH as a contributing factor to a broader array of SDGs. Two specific aims are to:

Describe the SDGs that are most closely aligned with MHH and the type of linkages between them; and

Highlight priority outcomes for sectors to monitor MHH directly, or to use as mechanisms for long-term tracking of MHH as a useful proxy measure for the advancement of a broader array of SDGs.

Rationale for linking MHH with the SDGs and monitoring MHH across sectors

Over the last decade there has been significant growth in attention to MHH, and more investment to evaluate if programs or policies have the desired impact, particularly in relation to girls in and out of school in low- and middle-income countries [Citation13–15]. However, despite this significant growth, MHH remains underacknowledged and underfunded, frequently dismissed as an extra, rather than essential consideration for development. The topic risks continued marginalization without explicit recognition of its role across development objectives. Furthermore, there are no consistent or agreed upon means of monitoring MHH to assess change and progress over time [Citation16]. Identifying linkages between MHH and the SDGs could help to establish monitoring efforts. Linking with the SDGs not only provides an opportunity to demonstrate how interconnected MHH is with other globally recognized priorities but may also facilitate the development of indicators and measures that could be integrated into systems already created for tracking each of the linked goals. If explicit linkages between MHH and the SDGs are not made clear and monitored, MHH may continue to be ignored or considered ‘outside the scope’ of various sectors and their priorities. Therefore, identifying these explicit linkages is critical to making sure MHH is appropriately acknowledged and addressed.

It is important to highlight that menstruation has been assumed to be linked to SDG 6.2, which calls for ‘paying special attention to the needs of women and girls’ in relation to sanitation and hygiene. While linkages with SDG 6.2 are clear, menstruation is not considered in any of the indicators to monitor SDG 6.2, which itself is considered gender blind [Citation17].

Methodological approach

To support future efforts to explore and more directly address the linkages between MHH and the SDGs, we undertook a consultation process to highlight key linkages and priority outcomes attentive to a broader range of SDGs, with a main focus on girls in and out of school in low- and middle-income countries. International experts representing key sectors [Health (sexual and reproductive; psychosocial wellbeing), Education, Gender, WASH] for girls came together to identify outcomes within their respective sectors to be prioritized by the following: (1) their hypothesized relation to MHH and (2) importance to achieving the SDGs. The process included a desk review and compilation of existing MHH indicators and priorities led by a Scientific Technical Advisory Group (STAG) (n = 7); the engagement of a Global Advisory Group (GAG) (n = 38) to feed into the analysis and its outputs; and a ‘Monitoring Menstruation’ task force meeting of sectoral measurement experts (n = 26). Activities were based on the aspirational goal: ‘Girls live in societies that enable them to be confident and knowledgeable about their menstruation and able to manage it with dignity, safety, and comfort, thereby promoting their health, wellbeing, and ability to realize their potential and equitable role in society’ [Citation18].

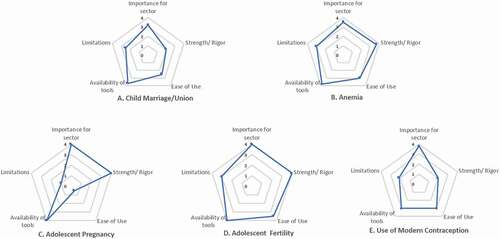

The specific methodological approach for identifying priorities among select sectors (see ; see supplemental files) included the following: [a] mapping of MHH outcome measures recognized to be of importance for girls, and of priority outcome measures for girls within key sectoral areas; [b] analysis of how addressing MHH aligns with identified key sectoral priorities, including attention to the SDGs; and [c] development of spider diagrams focused on the top three identified MHH-aligned outcome measures per relevant key sector. The spider diagram analyses assessed the readiness and appropriateness of identified outcome indicators for widespread uptake and use. The terminology being utilized refers to the following: goals describe the overall objective; targets provide a numerical value for achieving the goal; indicators are summary measures that attempt to estimate the status of a given target or goal; input measures assess the resources available for a given program or intervention; and outcome measures are used to capture short or medium-term change in a given population [Citation19]

After completing Steps 1–3 (see ), the priority outcomes identified by experts from each represented sector (Gender, Education, Health, WASH) were found to align with MHH in multiple ways for girls in and out of school in low- and middle-income countries [Citation18].

SDGs aligned with MHH

As depicted in (generated from content discussed in Steps 2–5 above), multiple SDGs were identified as relevant to MHH. While we will not reiterate the content of the table, we will highlight some key linkages. For example, in addition to the provision of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities, which SDG 6 does capture, materials to deal with menstrual flow are influenced by poverty and inequality (e.g. SDG1, no poverty). The need for adequate disposal systems for menstrual material waste has important implications for the larger environment (SDG 15), and for rural and urban planners in regard to basic services, including gendered sanitation (SDG 11).

Table 1. Relevance of Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and type of linkage (see )

As another example, menstruation is also linked to SDG 3.7 which aims to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health services (of which menstruation support is a critical element) and was also promised in the Beijing Platform for Action, and to SDG 5.3 which calls for the elimination of ‘child, early and forced marriage.’ In some contexts, the onset of menarche may trigger a girl’s vulnerability to early marriage [Citation20] given the perception that she is now able to reproduce [Citation13,Citation21].

Further, as a final example, menstruation relates to SDG 4 promoting ‘inclusive and equitable quality education.’ The lack of adequate, safe, clean toilets in schools may impact a girl or female teacher’s abilities to engage effectively in the learning process [Citation22–24].

Despite the relevance of menstruation across a range of global goals, the research, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and advocacy around MHH have primarily focused on the contribution of unmet MHH needs to outcomes such as school attendance and dropout. Other important linkages, such as impacts on psychosocial wellbeing [Citation15,Citation25], sexual and reproductive health [Citation26–28], and other educational outcomes have not received equivalent attention [Citation29–32]. Many sectors, such as Gender and Health, may not as of yet considered the role of MHH in contributing to the achievement of their own priority outcomes.

Linking sector priority outcomes with MHH and SDGs

The spider diagrams (Steps 4 and 5) enabled experts to appraise the top 3–4 priority outcomes per sector for their level of impact, relevance to MHH, and readiness for uptake more broadly. For the exercise (see exemplars in ), each group was asked to score each indicator in terms of importance for the sector, strength/rigor, ease of use, availability of tools (to measure), and limitations for uptake and scaled use. Insights included, for example, how from a sectoral perspective, the MHH alignment may not always be as evident given the lower position of MHH on the results chain in terms of contributing to the ultimate impact of a program or policy. Case in point, a national child marriage policy might not consider age of menarche as a relevant factor (see ; which only includes the top 3–4 selected priority outcomes (with related indicators) per sector, although additional outcomes were identified as aligned with MHH.).

Figure 3. Spider diagram analyses of Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) and MHH aligned outcome measures

Table 2. Examples of sector priority outcomes’ alignment with Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH)

In addition, prioritized outcome measures may require higher levels of financial or human capacity resources, limiting their usefulness for wider uptake and use at national and local levels. This is illustrated by the Education sector indicators, such that the availability and quality of ggender-sensitiveteacher training has a high perceived impact for education, with easy measurement of training presence or absence, but difficulties and high costs to conducting and assessing training quality. This differs from the outcome measure of transition (grade) rates for education, which serves as an output leading to an outcome and is captured easily, albeit not always rigorously in countries with poor data systems. Both are considered high impact in the Education sector, are related to MHH, and need gender supportive school environments, highlighting the potential role of menarche and MHH in hindering grade progression (see ).

Additional insights from the spider diagram exercise, which analyzed the 16 different outcome indicators identified across the sectoral areas (see ), included, for example, that while adolescent pregnancy is a high-impact measure, with those newly menstruating more vulnerable to becoming pregnant, it can be harder to measure and thus perhaps is not viable for national monitoring. In general, countries are more likely to measure adolescent birth rate than pregnancy given the ethical and logistical challenges of sampling and assessing who is pregnant. Identifying pregnancy among schoolgirls is hampered by the custom across different settings to expel girls from school [Citation33]; girls thus hesitate to declare pregnancy until it is clearly observable, and conducting pregnancy tests risks confidentiality disclosure. Another insight based on the spider diagrams, as portrayed above (see ), relates to anemia, a critical measure for girls’ and women’s health, with adequate tools available. However, the difficulty in routine collection of blood to measure hemoglobin reduces the utility of this measure.

Strengths and limitations

Key strengths of this undertaking included the extensive consultation process undertaken with stakeholders, including experts both experienced in menstrual health and more broadly among international expertise involved with decision-making for other sectors. Further, a systematic approach was used to examine key measures across sectors and document synergies. An important limitation was the potential bias amongst the experts included in the monitoring measures meeting group and global advisory group; although many were not engaged in MHH activities, they were selected based on their measurement expertise, role within global monitoring, and willingness to explore the potential alignments between MHH and priority sectors.

Conclusion

Important alignments exist between MHH and priority outcome measures for sectoral areas of relevance to girls in and out of school in low- and middle-income countries. These are essential to making progress on a broad array of SDGs. However, challenges related to limited sectoral understanding of MHH as relevant to making progress beyond sanitation, and insufficient validated outcome measures at programmatic and national levels, must be addressed. For the MHH community, future efforts should seek to (a) test these hypothesized relationships and the effect of unmet MHH needs to these outcomes; and (b) include these outcomes in trials for MHH interventions to assess impact on these sector-specific priority outcomes. Those who have not previously engaged with menarche and menstruation should (c) consider the contribution of MHH to these outcomes in national level monitoring, with the expectation that mediating or more proximal MHH indicators would likely be needed to claim that improvements in MHH were having the articulated impact on sectoral outcomes. MHH-related indicators should also be considered in problem and program theories related to these outcomes in other research efforts. Lastly, (d) there were a number of SDGs that may be perceived as either contributing (but not recognized) to making progress on MHH, or that could serve as a proxy for actual progress; these are important to consider as well moving forward. Efforts should go beyond low- and middle-income countries to incorporate the globe.

Author contributions

MS (conceptualized manuscript; initial draft); BC (additional conceptualization; significant inputs to initial draft); BT, PAP, GZ, TM, CG, AM, JH contributed to conceptualization and edits of multiple drafts; Monitoring Menstrual Health and Hygiene Group contributed analytic underpinning of content and a round of edits. Supplemental files included represent contributions from the range of authors included (citations on each). The MHH group beyond the core authors includes: Rockaya Aidara, Jura Augustinavicius, Nicole Bella, Emily Cherenack, Regina Guthold, Michelle Hindin, Richard Johnston, Caroline Kabiru, Virginia Kamowa, Kristen Matteson, Ella Naliponguit, Neville Okwaro, Elizabeth Omoluabi, Tom Slaymaker, Frances Vavrus, and Ravi Verma.

Ethics and consent

N/A

Paper context

There is an overdue need to assess the importance of menstrual health and hygiene across the entirety of the s17 Sustainable Development Goals, and highlight the sectors that would benefit from addressing menstruation when seeking to achieve goal-specific outcomes. To fully achieve the goals by 2030, it is necessary to recognize menstruation as a contributing factor. In this paper, we outline the potential linkages between menstrual health and hygiene and all of the goals.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (3.4 MB)Acknowledgments

Support for the initial analytic work that led to the content of this manuscript was provided by the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council and the Sid and Helaine Lerner MHM Faculty Support Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Loughnan L, Mahon T, Goddard S, et al. Monitoring menstrual health in sustainable development goals. Palgrave Handbook on Critical Menstrual Studies, Eds. Bobel C, Hasson KA, Kissling E, Fahs B, Roberts TA, Winkler I. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore, 2020. p. 577–592. Routledge: London, UK.

- Ibitoye M, Choi C, Tai H, et al. Early menarche: a systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178884.

- Sommer M. Menarche: a missing indicator in population health from low-income countries. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:399–10.

- Chisholm JS, Quinlivan JA, Petersen RW, et al. Early stress predicts age at menarche and first birth, adult attachment, and expected lifespan. Hum Nat. 2005;16:233–265.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Patel SV. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2017;14:30.

- Glynn JR, Kayuni N, Floyd S, et al. Age at menarche, schooling, and sexual debut in northern Malawi. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15334.

- Wodon Q, Male C, Montenegro C, et al. Educating girls and ending child marriage: a priority for Africa. The cost of not educating girls notes series. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2018 Nov.

- Sommer M. Ideologies of sexuality, menstruation and risk: girls’ experiences of puberty and schooling in northern Tanzania. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11:383–398.

- Sommer M, Sutherland C, Chandra-Mouli V. Putting menarche and girls into the global population health agenda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:24.

- Sommer M, Sahin M. Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1556–1559.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Guidance on menstrual health and hygiene. 2019. UNICEF: New York, USA.

- Raj A, Ghule M, Nair S, et al. Age at menarche, education, and child marriage among young wives in rural Maharashtra, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;131:103–104.

- Alam M, Luby SP, Halder AK, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among Bangladeshi adolescent schoolgirls and risk factors affecting school absence: results from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015508.

- Hennegan J, Montgomery P. Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. PloS One. 2016;11:e0146985.

- Hennegan J, Nansubuga A, Smith C, et al. Measuring menstrual hygiene experience: development and validation of the menstrual practice needs scale (MPNS-36) in Soroti, Uganda. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e034461.

- Hennegan J, Zimmerman L, Shannon AK, et al. The relationship between household sanitation and women’s experience of menstrual hygiene: findings from a cross-sectional survey in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:905.

- Sommer M, Zulaika G, Schmitt M, et al., Eds. Monitoring menstrual health and hygiene: measuring progress for girls on menstruation; Meeting report. New York: Columbia University and WSSCC; 2019.

- Mahon T, Caruso B. Foundational presentation from the ‘Monitoring menstrual health and hygiene: measuring progress for girls related to menstruation’ meeting. WSSCC and Columbia University: Geneva; 2019.

- Wodon Q, Male C, Montenegro C, et al. The cost of not educating girls: educating girls and ending child marriage: a priority for Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2018.

- Field E, Ambrus A. Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. J Political Econ. 2008;116:881–930.

- Sommer M, Caruso BA, Sahin M, et al. A time for global action: addressing girls? Menstrual hygiene management needs in schools. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001962.

- Chinyama J, Chipungu J, Rudd C, et al. Menstrual hygiene management in rural schools of Zambia: a descriptive study of knowledge, experiences and challenges faced by schoolgirls. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–11.

- Crankshaw TL, Strauss M, Gumede B. Menstrual health management and schooling experience amongst female learners in Gauteng, South Africa: a mixed method study. Reprod Health. 2020;17:1–15.

- Sumpter C, Torondel B. A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62004.

- Phillips-Howard PA, Hennegan J, Weiss HA, et al. Inclusion of menstrual health in sexual and reproductive health and rights. Lancet. 2018;8:E18.

- Phillips-Howard PA, Otieno G, Burmen B, et al. Menstrual needs and associations with sexual and reproductive risks in rural Kenyan females: a cross-sectional behavioral survey linked with HIV prevalence. J Women’s Health. 2015;24:801–811.

- Hennegan J, Tsui A, Sommer M. Missed opportunities: menstruation matters for family planning. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2019;45:55–59.

- Phillips-Howard PA, Nyothach E, Ter Kuile FO, et al. Menstrual cups and sanitary pads to reduce school attrition, and sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections: a cluster randomised controlled feasibility study in rural Western Kenya. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013229.

- Hulland KRS, Chase RP, Caruso BA, et al. stress, and life stage: a systematic data collection study among women in Odisha, India. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141883.

- Sommer M, Figueroa C, Kwauk C, et al. Attention to menstrual hygiene management in schools: an analysis of education policy documents in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Educ Dev. 2017;57:73–82.

- Phillips-Howard PA, Caruso B, Torondel B, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low- and middle-income countries: research priorities. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:1.

- Oruko K, Nyothach E, Zielinski-Gutierrez E, et al. ‘He is the one who is providing you with everything so whatever he says is what you do’: a qualitative study on factors affecting secondary schoolgirls’ drop out in rural western Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10:e014432.

- Polis CB, Hussain R, Berry A. There might be blood: a scoping review on women’s responses to contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes. Reprod Health. 2018;15:114.