ABSTRACT

Background

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is one of the most important strategies adopted by countries in achieving goals of sustainable development. To achieve UHC, the governments need the engagement of the private sector.

Objective

The aim of this study was to identify factors affecting private sector engagement in achieving universal health coverage.

Methods

The study is a scoping review that utilizes Arkesy & O’Malley frameworks. Data collection was conducted in MEDLINE, Web of Sciences, Embase, ProQuest, SID, and MagIran databases and the Google Scholar search engine. Also, manual searches of journals and websites, reference checks, and grey literature searches were done using specific keywords. To manage and screen the studies, EndNote X8 software was used. Data extraction and analysis was done by two members of the research team, independently and using content analysis.

Results

According to the results, 43 studies out of 588 studies were included. Most of the studies were international (18 studies). Extracted data were divided into four main categories: challenges, barriers, facilitators, goals, and reasons for engagement. After exclusion and integration of identified data, these categories were classified in the following manner: barriers and challenges with 59 items and in 13 categories, facilitators in 50 items and 9 categories, reasons with 30 items, and in 5 categories and goals with 24 items and 6 categories.

Conclusion

Utilizing the experience of different countries, challenges and barriers, facilitators, reasons, and goals were analyzed and classified. This investigation can be used to develop the engagement of the private sector and organizational synergy in achieving UHC by policymakers and planners.

Paper context

Main findings: Governments are key in healthcare provision, but the private sector’s involvement is increasingly vital for universal health coverage.

Added knowledge: This paper explores the evolving role of the private sector in universal health coverage, analysing barriers, challenges, facilitators, reasons, and goals for engagement while suggesting areas for further exploration.

Global health impact for policy and action: The private sector’s contributions to achieving Universal Health Coverage necessitate comprehensive policy frameworks and targeted actions to ensure equitable and sustainable health outcomes worldwide.

Responsible Editor Stig Wall

Background

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is the main policy that is greatly appreciated in the promotion of public health in different countries. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines and instructions emphasize achieving this goal. UHC ensures that everyone can access the full spectrum of quality health services they need, whenever and wherever they need them, without facing financial difficulties. It encompasses the entire range of essential health services, including health promotion, prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care throughout a person’s life [Citation1–3]. WHO has introduced it as a strategy in countries to achieve fair health services and ultimately healthy society [Citation4,Citation5]. On 18 October 2019 the United Nations (UN) General Assembly’s 74th session emphasized the importance of UHC in a political statement called ‘UHC: A collective movement toward a healthier world’ and recognized health and its dimensions as a prerequisite for sustainable development up to 2030 [Citation6].

The implementation of UHC varies among countries due to differences in infrastructure, economic conditions, health policies, and social factors. Each country must develop a customized plan that is tailored to its unique circumstances and available resources. Political commitment and the healthcare workforce competency also play critical roles in shaping UHC strategies. Consequently, no single model for UHC fits all countries, requiring tailored approaches for effective implementation [Citation7]. Based on special situations it may be necessary to take unique and different actions [Citation7–10]. These unique features of countries have made UHC one of the most challenging political processes that need support and engagement on behalf of stakeholders such as health policymakers and the private sector [Citation7]. For this reason, in UN statement (2019) in New York (UHC 2030) and articles 41, 45,50,53,54, and 80, it directly emphasized the importance and multilateral nature of acting in UHC and especially the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC [Citation11].

Today, one of the main and effective ways of facing health system challenges in all countries is utilizing private sector engagement and private–public partnership which can be called a multilateral and win–win policy. This engagement synergizes the capabilities of both parties in achieving their mutual goals [Citation12,Citation13]. It makes the private sector one of the most important and notable health service providers in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) [Citation14,Citation15].

The private sector can be a solution and a good opportunity for the growth of the health industry by providing facilities and innovative management and supporting the health system in achieving UHC [Citation12,Citation16]. Governments cannot ignore the role of the private sector in achieving UHC for their numerous activities in the health system [Citation17,Citation18]. Even the governments look at the private sector as a key, efficient, and cost-effective mechanism in the implementation of their goals and policies [Citation18,Citation19].

One of the reasons that goals such as justice and quality in UHC are threatened in many countries is the loose management and indifference to the private sector [Citation20]. The private sector only looks for its benefits in countries and is indifferent to the policies and goals of the health system. The reason for this indifference is that the management of health systems in these countries is not designed in a uniform and integrated form [Citation20,Citation21]. Moreover, in these countries, of private sector’s role and position in the health system are unclear and there is no plan for the collaboration and implementation of governments’ health policies in the private sector [Citation17].

Achieving UHC is a vital step toward ensuring equitable access to basic health services for all populations. The private sector’s engagement with this initiative is critical, as it has the potential to substantially enhance healthcare systems’ capacity, efficiency, and accessibility. However, the integration of private sector into UHC efforts is often met with numerous challenges, including regulatory barriers, financial constraints, and differing operational priorities. Understanding these barriers, as well as the facilitators and motivations for private sector involvement, is essential for formulating effective strategies that foster collaboration and leverage private sector resources. Therefore, this study was conducted to identify factors affecting private sector engagement in achieving universal health coverage.

Methods

Design

The present scoping review was conducted in 2021. Arkesy & O’Malley framework was utilized. This was the cognitive methodological framework that guided the scoping review, which was published in 2005. This framework consists of six steps: identifying the research question, identifying related studies, selecting/screening studies, categorizing/dividing data, summarizing, synthesizing, and reporting results, and providing operational guidelines and recommendations. The Arksey and O’Malley framework is a clear, adaptable, and systematic approach to scoping reviews and also, it allows for refinement of research questions and search strategies, ensuring comprehensive and relevant findings [Citation22].

Data sources

First, through preliminary review and asking for comments from two experts and one medical librarian, the keywords were specified and a search strategy was designed and implemented. The keywords were as follows: ‘Universal Health Coverage’, ‘Universal Coverage’, ‘Universal Healthcare Coverage’, ‘Universal Health Care Coverage’, UHC, ‘Private sector’, ‘Private health sector’, ‘Private provider’, ‘Private-for-profit providers’, ‘Private-not-for-profit providers’, ‘Non-state providers’, ‘Public-private mix’, ‘Private institutions’, ‘Private actors’, ‘Non-governmental organizations’, Cooperation, Collaboration, Participation, Partnership, Interaction, Engagement, Contrib*, Involvement. Search was done in MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Knowledge, Embase, ProQuest, SID, MagIran databases, and Google Scholar. The search time was 2008–2021. A manual search of several relevant journals and references of articles was conducted. Also, the official websites of organizations including WHO, World Bank (WB), and others were searched. To search for grey literature, we searched the Health Care Management Information Consortium, (HMIC), System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE), and European Association for Grey Literature Exploitation (EAGLE). (Search strategy supplementary file 1)

Inclusion criteria

Studies reporting the participation of the private sector in achieving UHC

Studies between 2008-2021

Exclusion criteria

Studies reporting public–private partnerships in other fields and outside health system

Studies that evaluated public–private partnerships with aims other than UHC

Studies that limited public–private partnerships in the health system only to outsourcing and a mere contract between two parties

Abstracts or congress abstracts without full text

Articles that did not report enough about the subject

Review process

The selection and screening process was conducted by two members of the research team, independently. The controversial items were solved through discussion and if needed were referred to the third person who was more knowledgeable and experienced. At first, the titles were evaluated and irrelevant studies were excluded. Then, the abstracts and full texts were evaluated to identify irrelevant studies. Endnote X8 software was utilized to evaluate titles, abstracts, and repeated items. To report selection and screening results PRISMA flowchart was utilized [Citation23–25].

Quality appraisal

Due to the condition of the scoping review, quality appraisal of reviewed sources was not conducted [Citation22].

Data extraction

To extract data according to the objectives and based on preliminary evaluation, the extraction form was designed by Microsoft Word 2016. At first, five papers data were extracted for pilot study and the problems in preliminary form were solved. Two researchers independently extracted data from the selected articles and solved the ambiguities by consulting with research team members. Extracted data included: the name of the author and publication year, country, objective(s), the type of private sector, activity, challenges and barriers, facilitators, reasons and goal of engagement, and the results of engagement (pros and cons).

Data analysis

The content analysis was applied in this study. This is a common method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting the patterns within the texts [Citation26–29]. Coding was done by two researchers, independently. Steps of the analysis included: reading the text several times, getting familiarized with data, identifying and extracting the primary codes, identifying the themes by placing similar codes together, revising the themes, naming and defining the themes, and ensuring the reliability of identified codes and themes by reaching agreement between the two coders and resolving the disputes through discussion.

Results

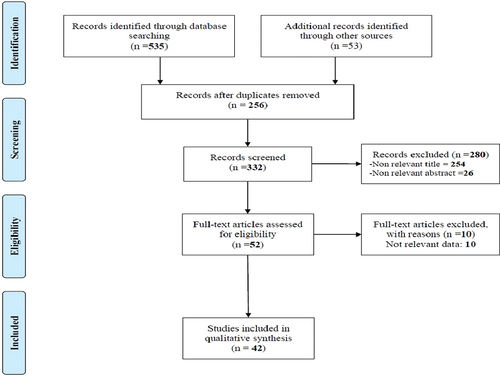

Out of 588 articles found through systematic and manual searches in databases and websites, 256 papers were excluded for repetition. Also, by screening titles and abstracts 280 articles were excluded for irrelevancy. Out of the remaining 52 articles, 10 were excluded for lack of enough data and not reporting the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC. Finally, 42 eligible papers were entered into the study (). The Supplementary file shows the summary of extracted data [Citation14,Citation18,Citation30–69] (Supplementary file 2).

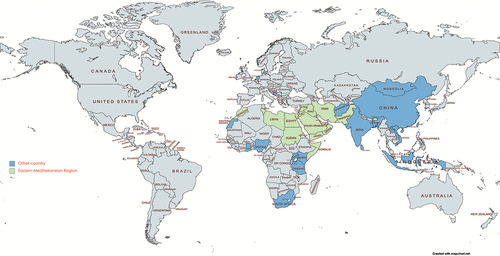

The studies were conducted in 20 countries with most of them to be carried out in India (5 cases). Asia and Africa had the highest number of included studies. Out of 42 articles, 16 were international and two were in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region ().

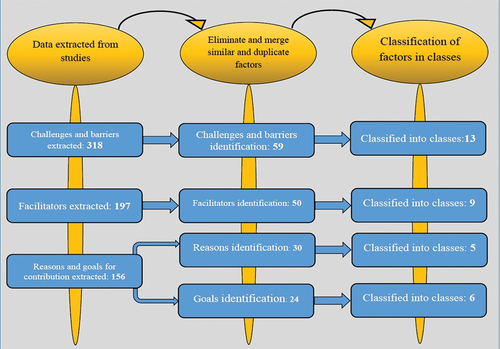

According to data analysis, the extracted data were classified into four main categories barriers and challenges, facilitators, reasons for engagement, and goals of engagement ().

Barriers and challenges of private sector engagement in achieving UHC

Initially, 318 barriers and challenges were identified. After the exclusion of repetitions and integration of homogenous and similar items, 59 challenges and barriers were classified under 13 categories. Regarding the frequency of barriers and challenges, economic challenges (nine items) and organizational challenges (eight items) were the most frequent categories ().

Table 1. Challenges and barriers to private sector engagement in achieving UHC.

Achieving UHC faces numerous challenges and barriers across various axes. Quality challenges include poor and inconsistent private sector services, exacerbated by inadequate monitoring. Regulatory issues stem from weak frameworks, poor execution, non-compliance with national guidelines, and lack of standardization in the private sector. Resource barriers involve inefficient use and unequal distribution of resources in both public and private sectors, undermining allocative efficiency. Also, human resource issues are characterized by difficulties in recruiting and retaining professionals, brain drain from the public sector to the private sector, high turnover rates, and overreliance on public sector-trained staff. Accreditation challenges include low-quality providers, high costs, lengthy procedures, and insufficient support for occupancy permits. Ethical hurdles involve corruption, conflicts of interest, and unethical practices like induced demand in private hospitals.

Financial barriers include inflexible healthcare plans, reliance on donor funding, high administrative costs, delayed reimbursements, high out-of-pocket expenses, low government salaries, unstable funding, and poor-quality care from providers. Governance challenges encompass weak processes, political interference, inadequate health policies, poor stewardship, unclear roles for the private sector in UHC, mistrust between sectors, and limited intersectoral collaboration. Organizational barriers include mismatched styles, dual-practice issues, poor patient load forecasting, weak contracts, lack of incentives, and power imbalances. Cultural barriers involve sociocultural influences, normative gaps, and low community participation. Service delivery challenges include heterogeneity, fragmented care, and a focus on curative care. Market barriers involve market power abuse, limited control over promotion, and equity protection. Information challenges include inadequate management systems, gaps in evidence and research, and poor reporting to health ministries.

Facilitators of private sector engagement in achieving UHC

Initially, 197 facilitators were extracted. After the exclusion of repeated items and integration of similarities, 50 facilitators remained. The identified facilitators were classified under nine categories. Capacity building (10 items) and economic facilitators (9 items) were the most frequent facilitators. Contracts (two items) were the less frequent category ().

Table 2. Facilitators for private sector engagement in achieving UHC.

Managing private sector involvement in healthcare requires robust regulation addressing social and economic goals and competition. Strengthening regulatory frameworks with quality accreditation and care standards is essential. Governments should regulate private health service delivery and implement rewards and sanctions to increase private sector participation. Enhancing the government’s capacity to develop, implement, and monitor regulations is crucial for effective engagement. Sustainable funding, donor support, and affordable service packages promote public-private cooperation. Implementing voucher programs, provider subsidies, pricing organizations, and strategic purchasing can reduce financial barriers.

Developing public sector capacity to manage private collaborations involves recognizing changes in authority and accountability, establishing formal communication channels, and involving the private sector in national health plans. Governments should lead in setting national health goals, using indirect governance tools, and collaborating with the private sector outside health to enhance access. Political commitment is needed to regulate the private sector’s role in ensuring universal healthcare access. National policies should focus on equitable facility distribution and inclusive guidelines. Establishing organizational structures, financial plans, and policy frameworks to include the private sector while minimizing political interference is crucial. Leadership, evidence-based decision-making, and comprehensive partnership assessment frameworks are key to improving healthcare outcomes.

Reasons for the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC

In this study, 156 reasons were extracted for the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC. After the exclusion of repeated items and integration of similar items, 30 reasons were identified. They were classified under five categories. Loose health systems, financial support, and resources were the most frequent ().

Table 3. The reasons for private sector engagement in achieving UHC.

The involvement of the private sector in achieving UHC is driven by several critical factors, primarily the weaknesses of the public health system. Public health infrastructure is often broken, with limited capabilities and gaps in service provision, leading to overburdened public sector hospitals. The private sector can rapidly scale up health programs and enhance service quality across both sectors, addressing these critical gaps. Rising healthcare costs, limited government financial capacity, higher out-of-pocket expenses, and a lack of public investment led to dependency on external donors. Political instability and economic crises exacerbate these financial challenges, while the private sector’s potential for high profits drives its involvement.

Resource and workforce barriers also highlight the need for private sector participation. Insufficient public health facilities and inadequate infrastructure and medical supplies further complicate these issues. Additionally, workforce shortages, less skilled providers, and a lack of qualified healthcare professionals in rural areas present significant challenges. Demographic changes, such as an aging population, population displacement, and a growing burden of non-communicable diseases, add to healthcare complexities. Community pressures, including patient demands for better healthcare and prevalent health inequalities, also drive the need for private sector involvement, as it can offer improved healthcare options and help reduce access and quality disparities.

Goals of the engagement of private sector in achieving UHC

After the evaluation of studies, 82 goals were extracted. After the exclusion of repeated items and integration of similarities, 24 remained. They were classified under 6 categories. Empowering health systems and resource management were the most frequent categories ().

Table 4. The goals of private sector engagement in achieving UHC.

The goals of private sector engagement in achieving UHC are aimed at enhancing various aspects of the health system. Strengthening health systems involves private sector investments in medical education and hospital development, which complement and integrate with local health systems. This fosters inter-sectoral collaboration to implement health-related interventions, enhancing the capacity and sustainability of health systems with private sector services supplementing governmental capabilities. Financial goals include improving the government’s commitment to healthcare financing by designing need-based benefit packages and purchasing private-sector health services.

Resource management by the private sector focuses on ensuring a geographic spread of health service providers, better resource allocation to the population, and creating new infrastructure. Promoting access aims to expand access to higher-quality health services and extend health insurance coverage, thereby improving population health coverage. The promotion of health services emphasizes regulating the private healthcare sector to improve patient safety, control unnecessary service delivery, and ensure quality care, maintaining high standards and aligning private sector operations with national health objectives.

Discussion

This scoping review provides an overview of the challenges faced by the private sector in achieving UHC, as well as the facilitators, reasons, and goals driving their engagement in this effort. Challenges and barriers with 59 items were classified into 13 categories, facilitators with 50 items were classified into 9 categories, and reasons (30 items) and goals (24 items) were classified into 5 and 6 categories, respectively.

The private sector faces several challenges in contributing to achieving UHC. These challenges were identified according to the different countries experiences. One major challenge to effective engagement is the diversity and heterogeneity of private sector health service providers, which increases the workload for the public sector and complicates collaboration efforts [Citation14,Citation44,Citation70]. Moreover, despite its advantages for the health system, a wide-scale private sector can be a threat to the integrity and sustainability of the health system if remains uncontrolled [Citation59,Citation63]. The reason for this threat is the tendency of 70% of people to use health services provided by the private sector which causes the public facilities to be less utilized and finally deviated from national strategic goals [Citation71]. Governmental challenges in the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC are other problems that greatly affect the national health system [Citation36,Citation53,Citation63,Citation64,Citation66]. Facing governmental challenges and trying to manage and solve them can contribute to a safe setting and bring trust among the stakeholders of private sector engagement in achieving UHC [Citation37,Citation66]. Also, possessing a reformist perspective on behalf of governments about governmental challenges can improve health system loose management and decrease political and utilitarian interferences by using evidence-based policy making and promotion of health service administrative capabilities it increases the efficiency and synergy of public and private sectors in achieving national strategic goals [Citation45,Citation63,Citation72]. Furthermore, by developing the capabilities in both public and private sectors to facilitate engagement and by its management, accurate implementation of the rules, eliminating ethical challenges in both public and private sectors in terms of conflicts of interest, and ensuring the quality of health services in both sectors, we can partially eliminate engagement challenges and accelerate countries achieving in UHC [Citation36–38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation45].

This study assessed the experiences of countries that identified the most effective facilitators and classified them under 9 categories. They can be used in developing national health strategic plans by policymakers and planners. One of the most important facilitators that can accelerate the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC is the use of efficient databases to collect and analyze information about the private sector in their tendency to cooperate and how they can cooperate with the public sector [Citation43,Citation45,Citation48,Citation51,Citation73]. Utilizing efficient databases, governments can identify and analyze the potentialities of the health private sector according to their needs and then fill the gaps in the public sector.

The development of the private sector in the health system and its increased effectiveness on public health has partially pushed the health system for marketing. This factor can have negative effects on the health system. One of the key facilitators that can play both a facilitator and an approach in avoiding health marketing and also propel and control private sector participation in achieving UHC is the regulations. Using regulations, the governments can adjust rules in the form of win–win games and control the private sector in achieving UHC [Citation14,Citation32,Citation35,Citation44,Citation47]. The Governments can correctly use the regulation as facilitators if they can fully control and manipulate factors such as the quality and quantity of services, allocation of health resources, providing competitive settings managing private sector share, and improving supervision [Citation50,Citation64,Citation74–77]. It is also necessary for governments to go beyond the control of the private sector and consider regulative, economic, political, social, and even organizational structures [Citation67].

The governments consider the private sector engagement in the health system to achieve their strategic goals. In this scoping review, we extracted the reasons and goals of private sector engagement in achieving UHC and classified them, respectively, under five and six categories. The loose and impotent public sector in providing qualitative health services and guaranteeing health security in LMICs is the most important reason for their need to use private sector engagement in achieving UHC [Citation30,Citation43]. Moreover, the health system is highly loose in some countries due to the lack of health financial resources or insufficient financial allocations on behalf of the government and inappropriate distribution of resources. On the other hand, the need for appropriate and accessible facilities increases the need for the presence of the private sector in the health system [Citation18,Citation51]. For this reason, governments try to build an integrated and sustainable health system and provide their citizens with qualitative health services as a valuable goal. Therefore, governments cannot ignore the engagement of the private sector due to their own needs and goals [Citation37,Citation42].

Limitation

However, as a limitation, the present study used one language (English) for the search and collection of data. While the studies on the engagement of the private sector in achieving UHC might be conducted in different countries with their native languages they have not been retrieved and evaluated in this study. Another limitation is that we narrowed the engagement of the private sector to the goal of achieving UHC; while in other fields of the health system, the public–private partnership might exist but not for achieving UHC.

Conclusion

The results suggested that despite many efforts in countries and the private sector engagement in achieving UHC, still many challenges and barriers exist. The present study tried to identify and classify the challenges, barriers, facilitators, reasons, and goals of this engagement. This study can be used by policymakers and planners in developing national health plans to achieve UHC with the private sector engagement. Moreover, utilizing the present results can predict the barriers and challenges that might happen in achieving UHC and provide situation-based solutions for these barriers to policymakers. The review showed that the more the goals of intersectional engagement are clear the more the consensus over solving these challenges that brings multilateral trust and facilitates and accelerates achieving UHC.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: N D, R R and S A-A

Data curation: H N, S S and E T-A

Formal analysis: N D and S A-A

acquisition: M M

Investigation: H N, S S and E T-A

Methodology: N D and R R

Project administration: N D and M M

Resources: N D

Supervision: N D and M M

Validation: N D and S A-A

Writing – original draft: N D

Writing – review & editing: N D, R R and M M

Ethics and consent

The protocol for the research project has been approved by the ethic committee at IUMS which is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. (Ethical approval code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.674)

Supplementary file 1.docx

Download MS Word (22 KB)Supplementary file 2.docx

Download MS Word (135.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all individuals and institutions who contributed to the completion of this scoping review article. First and foremost, we extend our heartfelt appreciation to the Research Deputy of Iran University of Medical Sciences for their support and encouragement throughout the research process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2024.2375672

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. 2010.

- Garrett L, Chowdhury AMR, Pablos-Méndez A. All for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2009;374:1294–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61503-8

- Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A, et al. Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. Lancet. 2012;380:933–943. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61147-7

- WHO. The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. World Health Organization. 2000.

- Evans DB, Saksena P, Elovainio R, et al. Measuring progress towards universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Political Declaration for the UN High-Level Meeting Meeting on UHC. 2019. Available from: https://wwwuhc2030org/news-events/uhc2030-news/political-declaration-for-the-un-high-level-meeting-meeting-on-uhc-555296/

- Savedoff WD, de Ferranti D, Smith AL, et al. Political and economic aspects of the transition to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:924–932. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61083-6

- WHO. World Health Report, 2010: health systems financing the path to universal coverage. World Health Report, 2010: health systems financing the path to universal coverage. 2010.

- Latko B, Temporão JG, Frenk J, et al. The growing movement for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2011;377:2161–2163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62006-5

- WHO. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. World Health Assembly Resolution. 2005;58.

- Sengupta A. Universal health coverage: beyond rhetoric. Municipal services project. Occasional Paper No. 2013.

- Davies P. The role of the private sector in the context of aid effectiveness: consultative findings document, final report, 2 February 2011. Paris: Organization for Cooperation and Development; 2011.

- Kraak VI, Harrigan PB, Lawrence M, et al. Balancing the benefits and risks of public–private partnerships to address the global double burden of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:503–517. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002060

- Morgan R, Ensor T, Waters H. Performance of private sector health care: implications for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2016;388:606–612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00343-3

- Bennett S, Hanson K, Kadama P, et al. Working with the non-state sector to achieve public health goals. World Health Organization. 2005.

- Vian T, McIntosh N, Grabowski A, et al. Hospital public–private partnerships in low resource settings: perceptions of how the lesotho PPP transformed management systems and performance. Health Syst Reform. 2015;1:155–166. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2015.1029060

- Clarke D, Doerr S, Hunter M, et al. The private sector and universal health coverage. Bullet World Health Organ. 2019;97:434. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.225540

- WHO. The private sector, universal health coverage and primary health care. World Health Organization. 2018.

- Koohpayehzadeh J, Azami-Aghdash S, Derakhshani N, et al. Best practices in achieving universal health coverage: a scoping review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021;35:1–35. doi: 10.47176/mjiri.35.191

- McPake B, Hanson K. Managing the public–private mix to achieve universal health coverage. Lancet. 2016;388:622–630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00344-5

- Derakhshani N, Doshmangir L, Ahmadi A, et al. Monitoring process barriers and enablers towards universal health coverage within the sustainable development goals: a systematic review and content analysis. Clin Outcomes Res. 2020;12:459–472. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S254946

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 PubMed PMID: 19622551; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2714657. Epub 2009/07/23.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 PubMed PMID: 19621072; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2707599. Epub 2009/07/22.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 PubMed PMID: 20171303. Epub 2010/02/23.

- Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Grbich C. Qualitative data analysis: an introduction. Sage; 2012.

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

- Ejughemre UJ. Accelerated reforms in healthcare financing: the need to scale up private sector participation in Nigeria. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;2:13–19. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.04 PubMed PMID: 24596895; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3937949. Epub 2014/03/07.

- Roy B. Aspiring for universal health coverage through private care. Econ Political Wkly. 2017;52:15–18.

- Hallo De Wolf A, Toebes B. Assessing private sector involvement in health care and universal health coverage in light of the right to health. Health Hum Rights. 2016;18:79–92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001244 PubMed PMID: 28559678; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5394993. Epub 2017/06/01

- Iyer V, Sidney K, Mehta R, et al. Availability and provision of emergency obstetric care under a public-private partnership in three districts of Gujarat, India: lessons for universal health coverage. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1:e000019. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000019 PubMed PMID: 28588914; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5321320. Epub 2016/04/13.

- Iyer V, Sidney K, Mehta R, et al. Characteristics of private partners in Chiranjeevi Yojana, a public-private-partnership to promote institutional births in Gujarat, India – lessons for universal health coverage. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185739

- Cowley P, Chu A. Comparison of private sector hospital involvement for UHC in the western pacific region. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5:59–65. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2018.1545511 PubMed PMID: 30924748. Epub 2019/03/30.

- Rao KD, Paina L, Ingabire MG, et al. Contracting non-state providers for universal health coverage: learnings from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:127. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0846-5 PubMed PMID: 30286771; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6172768. Epub 2018/10/06.

- Maluka S. Contracting out non-state providers to provide primary healthcare services in Tanzania: perceptions of stakeholders. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7:910–918. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.46

- Maluka S, Chitama D, Dungumaro E, et al. Contracting-out primary health care services in Tanzania towards UHC: how policy processes and context influence policy design and implementation. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:118. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0835-8 PubMed PMID: 30286767; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6172831. Epub 2018/10/06.

- Lu JFR, Chiang TL. Developing an adequate supply of health services: Taiwan’s path to universal health coverage. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.017

- Olu O, Drameh-Avognon P, Asamoah-Odei E, et al. Correction to: community participation and private sector engagement are fundamental to achieving universal health coverage and health security in Africa: reflections from the second Africa health forum. BMC Proc. 2019;13:11. doi: 10.1186/s12919-019-0182-9 PubMed PMID: 31827602; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6889179. Epub 2019/12/13.

- Ssennyonjo A, Namakula J, Kasyaba R, et al. Government resource contributions to the private-not-for-profit sector in Uganda: evolution, adaptations and implications for universal health coverage. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:130. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0843-8 PubMed PMID: 30286757; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6172798. Epub 2018/10/06.

- Wadge H, Roy R, Sripathy A, et al. How to harness the private sector for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2017;390:e19–e20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31718-X

- Wong EL, Yeoh EK, Chau PY, et al. How shall we examine and learn about public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the health sector? Realist evaluation of PPPs in Hong Kong. Soc Sci & Med (1982). 2015;147:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.012 PubMed PMID: 26605970. Epub 2015/11/26.

- McPake B, Hanson K. Managing the public-private mix to achieve universal health coverage. Lancet. 2016;388:622–630. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00344-5 PubMed PMID: 27358252.

- Shroff ZC, Rao KD, Bennett S, et al. Moving towards universal health coverage: engaging non-state providers. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:135. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0844-7 PubMed PMID: 30286766; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6172788. Epub 2018/10/06.

- Nabyonga-Orem J, Nabukalu JB, Okuonzi SA. Partnership with private for-profit sector for universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities and caveats. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4:e001193. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001193

- Kumar R. Public–private partnerships for universal health coverage? The future of “free health” in Sri Lanka. Globalization Health. 2019;15. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0522-6

- Ota MOC, Kirigia DG, Asamoah-Odei E, et al. Proceedings of the first African Health Forum: effective partnerships and intersectoral collaborations are critical for attainment of universal health coverage in Africa. BMC Proc. 2018;12:8. doi: 10.1186/s12919-018-0104-2 PubMed PMID: 29997696; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6031170. Epub 2018/07/13.

- Suchman L, Hart E, Montagu D. Public-private partnerships in practice: collaborating to improve health finance policy in Ghana and Kenya. Health Policy Plann. 2018;33:777–785. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy053 PubMed PMID: 29905855; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6097457. Epub 2018/06/16.

- Tsevelvaanchig U, Narula IS, Gouda H, et al. Regulating the for-profit private healthcare providers towards universal health coverage: a qualitative study of legal and organizational framework in Mongolia. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33:185–201. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2417

- WHO. Role and contribution of the private sector in moving towards universal health coverage. 2016.

- Stallworthy G, Boahene K, Ohiri K, Pamba A, et al. Roundtable discussion: what is the future role of the private sector in health? Globalization Health. 2014;10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-10-55

- Clarke D, Doerr S, Hunter M, et al. The private sector and universal health coverage. Bullet World Health Organ. 2019;97:434–435. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.225540

- Grieve A, Olivier J. Towards universal health coverage: a mixed-method study mapping the development of the faith-based non-profit sector in the Ghanaian health system. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:97. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0810-4 PubMed PMID: 30286758; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6172851. Epub 2018/10/06.

- Perumal-Pillay VA, Suleman F. Understanding the decision making process of selection of medicines in the private sector in South Africa – lessons for low-middle income countries. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13:17. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00223-5 PubMed PMID: 32477570; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7240914. Epub 2020/06/02.

- Sieverding M, Onyango C, Suchman L, et al. Private healthcare provider experiences with social health insurance schemes: findings from a qualitative study in Ghana and Kenya. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192973

- Meliala A, Hort K, Trisnantoro L. Addressing the unequal geographic distribution of specialist doctors in Indonesia: the role of the private sector and effectiveness of current regulations. Soc Sci & Med (1982). 2013;82:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.029 PubMed PMID: 23453314. Epub 2013/03/05.

- Onoka CA, Hanson K, Mills A. Growth of health maintenance organisations in Nigeria and the potential for a role in promoting universal coverage efforts. Soc Sci & Med (1982). 2016;162:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.018 PubMed PMID: 27322911. Epub 2016/06/21.

- Doherty J, editor. Achieving universal health coverage in East and southern Africa: what role for for-profit providers. International Conference on Public Policy, Panel session T03P13, Milan, Italy; 2015.

- Titoria R, Mohandas A. A glance on public private partnership: an opportunity for developing nations to achieve universal health coverage. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6:1353. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20190640

- Shah U, Thakur H. Achieving universal health coverage through public private partnerships: a study of trends in the public private partnerships in India.

- Roland J, Bhattacharya-Craven A, Hardesty C, et al. Healthy returns - the role of private providers in delivering universal health coverage. Report of the WISH role of the private sector in healthcare forum 2018. 2018.

- Appleford G. Private sector accountability for service delivery in the context of universal health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Hung YW, Klinton J, Eldridge C. Private health sector engagement in the journey towards universal health coverage: landscape analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization Unpublished manuscript; 2020.

- Js K. Engaging the private health sector to advance universal health coverage: a case study from the WHO regional office for Eastern Mediterranean Region. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Hellowell M, O’Hanlon B. Principles for engaging the private sector in universal health coverage: a background report for the advisory group on the governance of the private sector for UHC. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- WHO. Private sector engagement for advancing universal health coverage. World Health Organization. 2018.

- Wu R, Li N, Ercia A. The effects of private health insurance on universal health coverage objectives in China: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2049. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062049

- UHC2030. Private sector contributions towards universal health coverage UHC2030 private sector constituency statement. 2019. Available from: https://wwwuhc2030org/fileadmin/uploads/uhc2030/Documents/Key_Issues/Private_Sector/UHC2030_Private_Sector_Constituency_Joint_Statement_on_UHC_FINALpdf

- Asiabar AS, Azami-Aghdash S, Rezapour A, et al. Economic consequences of outsourcing in public hospitals in Iran: a systematic review. J Health Adm. 2021;24:68–83. doi: 10.52547/jha.24.1.68

- WHO. Health systems strengthening in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean region: challenges, priorities and options for future action. 2012.

- Clarke D, Rajan D, Schmets G. Creating a supportive legal environment for universal health coverage. Bullet World Health Organ. 2016;94:482–. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.173591

- Widdus R. Public-private partnerships for health require thoughtful evaluation. SciELO Public Health; 2003.

- Kumaranayake L, Lake S. Regulation in the context of global health markets. Health policy in a globalising world. Cambridge University Press; 2002. p. 78–96.

- Perrot J. Different approaches to contracting in health systems. Bullet World Health Organ. 2006;84:859–866.

- WHO. Assessing the regulation of the private health sector in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Egypt. 2014.

- Derakhshani N, Maleki M, Pourasghari H, et al. The influential factors for achieving universal health coverage in Iran: a multimethod study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06673-0 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC34294100.