ABSTRACT

In this article, we suggest incorporating visual images into peace education through interactive peace imagery (IPI). We will show, and illustrate with examples from our work, that interactive teaching creates a space for students to reflect upon their socializations, including visual ones, without which image interpretation cannot be fully explained. We begin by exploring photojournalism as a media that, while providing raw material for peace education, does not serve as a model for image interpretation. Emphasizing images’ interpretive openness, we suggest an alternative approach (IPI) that unearths, (re)vitalizes, and capitalizes on the plurality of meanings images carry with them. We focus on digitization and active interaction (seeing – changing – sharing) in a non-hierarchic teaching environment. In IPI, the classroom becomes a network: students interactively engage with visual images by regarding existing images, elaborating on them, changing them, sharing the changed images with their fellow students, or producing original images. Students become involved in the production process and their responsibility for both the image and the knowledge claims attached to it increases. Critical reflections on the suggested procedure in terms of quantity, time, authority, and violence conclude the paper.

Introduction

Once again, politics and the media are dominated by images of confrontation, polarization, and armed aggression. War sidelines peace, war images sideline peace images, destruction and human suffering sideline human imagination and creativity. In consequence, peace education is once again asked to mobilize what John Paul Lederach calls ‘the moral imagination’ – ‘the capacity to imagine and generate constructive responses and initiatives that, while rooted in the day-to-day challenges of violence, transcend and ultimately break the grips of those destructive patterns and cycles’ (Lederach Citation2005, 29). Once again, in other words, we are asked to imagine – and to image – peace. In the visual arts, however, ‘aspirations for peace are often represented through depictions of war and violence’ (Richmond Citation2008, 2). Although exceptions exist (see Mitchell Citation2020), such works risk confirming the very conditions they wish to transcend. The news media and photojournalism, by documenting war and destruction, also produce a violent picture of the world. By so doing, they create, as Johan Galtung (quoted in Haagerup Citation2019) has put it, ‘a total[ly] biased picture of reality. The perception of reality in the public becomes overly negative’. ‘[W]hat initially meets the eye’ – literally – appears destructive and violent, necessitating (but simultaneously rendering difficult) development of the capability of perceiving things beyond what was initially seen (Lederach Citation2005, 26–27), moving our imagination from war to peace or to peace as a potentiality.

Peace images enable viewers to (re-)discover peace in established places, in new and unusual, mundane places, and in places where peace is conspicuous mainly by its absence. Such images can represent peace beyond negative peace images communicating the need for peace by showing its absence on which photojournalism and the media rely. However, images have social impact only when they are seen and shared and when observers have learned how to deal with them. Which is why visual literacy is an important part of peace education: we live ‘in a world saturated, no, hyper-saturated with images’ (Sontag Citation2003, 105) but the visual ingredients of peace and conflict are not always included in peace education.

Importantly, research on the visual dimension of peace is not only about images. It is about images of peace but it is also about images and peace, i.e. the complex relationship between images and peace. Images serve as vehicles with which to explore a wide range of subjects pertaining to peace and conflict including the construction of both sameness and otherness, gender relations, the everyday dimension of peace and conflict, human migration but also, obviously, armed aggression and its consequences, all of which are communicated to us through the media relying, to a large extent, on visual discourses, i.e. images plus accompanying texts (or the other way round: text accompanying images; see below). While we learn in peace education how to analyze written and verbal text, how to read documents and how to make sense of interviews, however, we do not always learn how to analyze images, although a huge repertoire of methodological tools is readily available. Thus, the very fact that images are ubiquitous and that we use them routinely in our daily communication makes us believe that dealing with them in peace education and peacebuilding were easy. It is not.

In this article, we want to suggest incorporating visual images into peace education through what we call interactive peace imagery (IPI). All terms are equally important here: interactive because the digital world cannot be thought of without interaction; peace because peace cannot be imagined by solely or primarily focusing on violence; imagery because images evoke imaginations and they do so differently from verbal or written texts. IPI is not the only way to use images in peace education; several scholars have described alternative approaches (Weber Citation2011; Bleiker Citation2015; Callahan Citation2015; Delgado Citation2015; Vastapuu Citation2017; 27–53; Särmä Citation2018; Harman Citation2019; Möller, Bellmer, and Saugmann Citation2022). Our approach is informed by knowledge produced in visual peace research and media and interaction studies and makes this knowledge available to peace education. We argue that in an era dominated by social media and the internet, peace education must take full advantage of the possibilities digitization offers, consciously inviting interaction among students and capitalizing on the plurality of meanings that all images carry with them. We will show, and illustrate with examples from our work, that IPI creates a space for students to reflect upon their social positions and their socializations including visual ones within a culture dominated by visual images. It helps students to understand how the way they see and think peace is influenced by their cultural and visual socializations and how, in turn, they can influence these socializations by seeing and thinking peace differently. Students as inter-actors are participants in visual peace politics, actively contributing to peace (even though the extent of such contribution cannot be established precisely).

We proceed as follows: first, we explore photojournalism as a genre that provides raw material in abundance for peace education; at the same time, standard photojournalistic procedures with regard to image interpretation do not serve as a model for visual peace education. We will show why this is so and suggest, secondly, an alternative approach that unearths and (re)vitalizes the plurality of meanings that images carry with them. Thirdly, we elaborate on images in peace education by focusing on digitization and interaction in terms of seeing – changing – sharing in a non-hierarchic teaching environment. In IPI, the classroom becomes a network: students interactively engage with visual images by regarding existing images, elaborating on them, changing them, sharing the changed images with their fellow students, or producing original images. We conclude the paper with self-critical reflections on the suggested procedure in terms of quantity, time, and authority.

Photojournalism, interpretive interventions, and the classroom

Images can serve as vehicles with which to elaborate on essential political, aesthetic, and ethical questions that keep tormenting peace education: How and where do we see peace? How can we imagine peace in images conditioned by violence? Is it possible to utilize visual images in teaching without reproducing the violence that (some) images communicate? If violence is the condition for the possibility of some images, what does that mean for our use of these images: do we become complicit with violence or do we somehow manage to transcend it? Can we bear witness visually to violence without ourselves committing acts of visual violence? Can we use traumatic images of human suffering in teaching situations without traumatizing our students and contributing to the dehumanization of the subjects depicted? How can we look behind images to understand what they do not show? Visual peace research (see Möller Citation2013) reflects upon these and related issues from the perspective of what it means to be a spectator of images; educators and students are spectators, too, but no-one is only a spectator. Using images in peace education means thinking with images about peace and its conditions of possibility – most basically: how can peace be represented visually and how can such representation contribute to peace? – thus encouraging self-reflection about our subject positions as students of peace but also about our role as citizens. The use of images in peace education thus appeals to what Lederach calls ‘sensuous perception’ – the ‘capacity to use and keep open a full awareness of that which surrounds us by use of our complete faculties’ (2005, 108).

We suggest that it will be difficult to generate and communicate new knowledge on peace and new peace politics while looking exclusively at violence. It is no doubt true that the visual is strongly linked with violence, not only representing violence but also contributing to it. Subjects to the photography of others often feel violated in their privacy and dignity, especially when in pain. Photographs of human suffering ‘are performative artefacts that help to create or prolong the very suffering they document’ (Reinhardt Citation2007, 17). Can we regard the pain of others (Sontag Citation2003) without ourselves inflicting, as spectators, pain on others (or ourselves)? ‘Violence’, Mirzoeff (Citation2011, 292) argues, ‘is the standard operating procedure of visuality’. Photography, in particular, has often been accused of having had ‘an intimate relationship with violence’ since its inception (Reinhardt Citation2018, 321). Yet, it has also had an equally important and often ignored ‘role in civic life and democratic struggle’ (Reinhardt Citation2018, 321; see also Azoulay Citation2008; Brunet Citation2019) including the development of human rights discourses and practices (Sliwinski Citation2011). It is this tradition that visual peace research wishes to expand on and that we want to make available to peace education, approaching visual images pro-actively and interrogating their peace potentialities (see Allan Citation2010; Ritchin Citation2013, 122–141; Möller Citation2013, Citation2019;Mitchell Citation2020).

A good starting point for visual peace education is photojournalism. Photojournalistic images are readily available, they contribute massively to how we perceive the world, and they are closer linked in our perception to the real world which they claim to document than, for example, art photographs or paintings. Photo editors occasionally complain that they represent ‘a medium which is almost everywhere considered secondary to the text’ (Ritchin Citation1999, 99) with images merely illustrating what has already been established textually. However, it seems more appropriate to conceive of the word – image relationship in photojournalism in terms of an ‘intellectual stereoscopic effect: the image gains in profile through the verbal information conveyed in the caption; from the accompanying image this information gains persuasive power’ (Gilgen Citation2003, 56). Photojournalists want to be understood correctly and use both words and images to communicate their message. In other words, they want to exert control over meaning. Which is why in photojournalism, image-only forms of representation are the exception. Captions are the rule although ‘even an entirely accurate caption is only one interpretation, necessarily a limiting one, of the photograph to which it is attached’ (Sontag Citation1979, 109). Rather than limiting perception to the interpretation offered in the caption, exploring an image’s – any image’s – multiple interpretations is part of peace education, reflecting that ‘we still must learn how to become spectators of images’ (see Emerling Citation2012, 165) rather than (merely) readers of captions.

Regarding an image only in light of the interpretation suggested in the caption is problematic: it undermines images’ capability of inviting different interpretations simultaneously (depending on who regards them). Furthermore, words and images ‘not only tell us things differently, they tell us different things’ (MacDougall Citation1998, 257), identification of which, however, is not what photojournalism primarily aspires. Again, this is completely understandable: as the normal viewing relationship does not necessitate professional mediation in order for the viewer to make sense of a given image (any sense, any image), journalists worry that they might be misunderstood if they presented only images to readers. As the image may not give readers assurance as to the conditions depicted, words may – or at least invite comparison of the intended meaning with the perceived meaning.Footnote1

The classroom situation, however, is different. Here, images can be addressed visually by simply asking: ‘what do you see?’ before providing any background information about the conditions depicted or the photographer’s intentions. A professional mediator, an educator, may not be needed for the students to see something, but he or she is present all the same, facilitating the students’ multiple encounters with the image. Essentially, his or her facilitation differs from the procedures applied in photojournalism (fixing meaning) – which is why photojournalism, while often offering the raw (i.e. visual) material does not serve as a role model for IPI when it comes to image interpretation.

Once the basics of photojournalism and the word – image relationship are established, Interactive Peace Imagery can move on to:

develop a state-of-the-art agenda for visual peace education in terms of digitization, inter-activity, and audience participation;

interactively communicate this agenda to students;

invite students to produce peace images;

analyze both the process and the resulting images and explore how different cultural and visual socializations among students influence individual visualizations of peace; and

critically reflect upon the whole procedure.

Images in peace education

Interactive Peace Imagery takes advantage of the possibilities interaction offers: image users such as students interactively engage with visual material by looking at existing images, analyzing them, modifying them, and sharing the modified images with other users thus inviting them basically to do the same thing. Viewers morph into ‘co-authors’ (Emerling Citation2012, 67) of both a work’s meaning(s) and the work itself. More than ever before, then, viewing becomes a process of active meaning making in communication with others, based on image analysis and followed by the production of images, either as original or as appropriated images (Möller, Bellmer, and Saugmann Citation2022).

Following Audrey Bennett (see below), the basic, one-way, active mode of interaction includes looking at and interpreting an image. The two-way active mode of interaction requires changing and modifying images, removing or adding images. The three-way active mode, finally, requires users to share changed and added images with other users who, then, do the same thing in a process that is potentially infinite. Active interaction thus is a process of seeing – changing – sharing. When focusing on peace images or images of peace, it must be acknowledged that these concepts are open concepts, loosely defined, reflecting the absence of a universally agreed peace definition; visual peace education reflects this. Furthermore, it is an integral component of interactive visual work that, through narrative openness, plurality of meanings, and the absence of hierarchic ordering or other forms of ranking, it enables new forms of engagement thus envisioning new teaching formats.

1) IPI, visuality and digitization

IPI takes advantage of the possibilities digitization and digital images offer in a classroom or digital teaching scenario. Digital images are fluid and malleable which can neither be grasped nor utilized in peace education by following, conventionally, a rather static understanding of the image and an understanding of the spectator as actively interrogating the meaning of a given image without contributing herself to this image’s generation or alteration. Images’ fluidity and malleability also influence how images operate in and on society. Digital images are hard to pin down, they are in flux and only loosely coupled to an ‘original’. Digital images are not just variations of their analogue predecessors, to be understood by means of the concepts developed to make sense of analogue images (see Ritchin Citation2009, 141–161). Indeed, relying on established theories and methods (derived from the work of, and inextricably connected with, such famous and authoritative scholars as Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Susan Sontag, to name but a few) when studying something that is essentially new is always problematic, inviting misinterpretation. The belief in photography’s objectivity and credibility, the belief in mechanical and, therefore, objective reproduction of that which is front of the lens, independent of the photographer and the technology used to produce an image, still governs to some extent our understanding of photojournalism. The history of photography is a history of photo manipulation (sometimes crude, sometimes more refined) but even without deliberate manipulation, images always tell different stories simultaneously and their relationship with that which they claim to represent is a tricky one, as Jacques Rancière explains:

The image is not a duplicate of a thing. It is a complex set of relations between the visible and the invisible, the visible and speech, the said and the unsaid. It is not a mere reproduction of what is out there in front of the photographer or the filmmaker. It is always an alteration that occurs in a chain of images which alter it in turn

It is certainly part of peace education to unweave this set of relations, carefully analyzing the legacy of photojournalism – documentation in terms of verisimilitude – and deconstructing the meanings and interpretations of individual images.Footnote2

To be sure, there is longing for (some degree of) assurance alleged to be found in images – assurance that analogue images, since photography’s inception, had always been tasked with delivering without ever having been capable of delivering it in fact. Pictures ‘alone cannot’ – and have never been able to – ‘make for us the discriminations that we might like to make’ (Hirsch Citation1997, 71). With digitization, the belief in photographic truth and verisimilitude is, once again, challenged. Now, photo-theoretical inertia is especially problematic (see Lister Citation2013, 3–8) because we are not dealing with mere variations in image making that could be addressed by mere variations in theory. Such inertia tends to result in ‘distortions, vast blind spots, and wild misinterpretations’ (Paglen Citation2016) based on a kind of visual phantom pain: even if it is not a photograph, conventionally understood, but a machine or computer generated image, ‘if you see an image as a photograph, it is a photograph – for you’,Footnote3 with all which that implies in terms of documentation, objectivity, verisimilitude, author – spectator relationship and so on. Lamenting about a golden age when a photograph still was a photograph does not help. What does help, however, is acknowledgement of the teaching possibilities the new digital world offers (without ignoring the risks).

The internet invites participation as never before, redefining the role of spectators and image producers. The classroom becomes a network; in online teaching, it already is a network. Today, ‘media participation can be seen as the defining characteristic of the internet in terms of its hyperlinked, interactive and networked infrastructure and digital culture’, Deuze (Citation2007, 245) observed fifteen years ago. Thus, the producer – observer – image triangle is different from established notions of ‘framed, fixed and stable images viewed (or “read”) by equally centred and motivated viewers’ (Lister Citation2013, 7).

Indeed, it is in the nature of digital networked images to exist in a number of states that are potential rather than actual in a fixed and physical kind of way. Such images are fugitive and transient, they come and they go, they may endure for only short periods of time and in different places

Already at this stage, IPI calls for cooperation between educators and students including mutual learning: educators, often puzzled by students’ activities on social media, have to understand that most students are quite capable users of current digital formats although they do not necessarily possess a sense of the conceptual and theoretical underpinnings of the technologies they use; students, largely unaffected by image theories and histories, have to understand that the conceptual baggage that the educators carry with them might help them, too, to better understand the technologies they are routinely using and to develop critical consciousness of the relationship among the visual, power, and knowledge.Footnote4

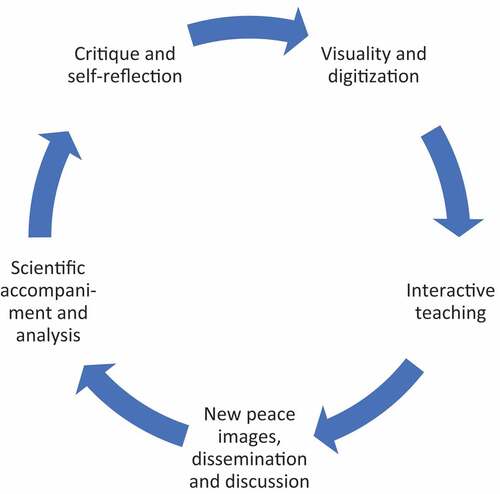

Engagement with digital images can take place both in the classroom and in online teaching. Digitization equals interaction and change: digital images are meant to be experienced, modified, and shared; they ‘can and will be linked, transmitted, recontextualized, and fabricated’ (Ritchin Citation2009, 141). IPI integrates the open-endedness of the production and reflection process of digital images into its approach to teaching, offering completely new possibilities for student participation (see below). As digitization constantly evolves, teaching has to evolve in parallel; to some extent, teaching always comes after, in response to technological innovations. Which is why in , the cycle begins anew after Critique.

2) Interactive teaching

Interactive documentaries anticipate the future of the documentary format and, perhaps, also the future of visual peace education: ‘new, creative, non-linear forms of engagement and interaction between viewers, authors and the material itself, [open] up the terrain for a new politics of viewing and meaning-making’ (Favero Citation2013, 260) and new teaching formats. ‘Today’, Bennett notes, ‘images communicate most effectively when they engage users in active interaction’ (Bennett Citation2012, 63) thus turning passive spectators (a myth anyway) into inter-actors. Active interaction turns students into image-makers, engaging with images rather than passively consuming them. How to interact actively? How to achieve interactivity? Different teaching scenarios require different approaches, given different visual socializations, experience, and sensitivities among students and educators. During teaching, we must interrogate habits of seeing which are always culturally embedded and, thus, more or less stable, and subsequently engage in different modes of active interaction, as developed by Bennett.

Most basically, there is the one-way, active mode of interaction, in which the user looks at the image to begin the process of interpretation and uses other senses, like her sense of touch, to interpret the image and complete the communication transaction (Bennett Citation2012, 62). Business as usual, independent of the character of an image (analogue or digital), following the educator’s question: what do you see in this image? As different students are likely to see different things and to value the things they see differently, already at this stage communication among students can start. The educator should assume a rather low profile, dispense with mediation in search of consensus, and facilitate the situation such that conversations can unfold smoothly. It is essential that the educator regards individual interpretations as equally valuable including interpretations such as ‘There is nothing to see’ or ‘I have no idea what I see’, encouraging students to articulate their perceptions without fear of being ‘wrong’.

‘I do not want to see this’ is a perfectly legitimate response, especially to images showing acts or consequences of violence, as many negative peace images do. Educators need to warn students if they are to show such images, giving them a chance to leave the room prior to the viewing experience without fear of discrimination. Starting with seemingly unproblematic images and subsequently moving on to more problematic ones may be a strategy but it risks succumbing to what James Elkins calls ‘the kitsch economy of perpetual inflation’ (Elkins Citation2011, 185), visual escalation and increase in the intensity of the viewing experience where every image is more shocking or more spectacular than the previous one. Furthermore, there is no universal standard for a ‘problematic’ image; what qualifies as such reflects who you are, your individual experience and socialization. A seemingly tranquil seascape image – ‘pure poetry’ in a writer’s words (Seidler Citation2020, 470) – may evoke peace of mind on the part of some people but, as one student remarked, traumatic memories on the part of those who had to cross the Mediterranean Sea on their journey to Europe.

The educator does not judge individual perceptions as appropriate or inappropriate but, rather, allows different interpretations to stand side-by-side. Indeed, educators have to unearth habits of seeing which are often taken-for-granted and unconscious. They aren’t really habits of seeing anyway but rather habits of listening to others telling us what we see (Berger Citation2013). It is the educator’s task, then, to encourage the students to become agents of their own image interpretation: to trust and believe in what they themselves see and to try to understand both why they see what they see and how they visualize what they see (see Pylyshyn, Citation2006, for the relationship between seeing and visualizing and Morris Citation2014, for the relationship between seeing and believing). Finally, educators should respect that there is ‘something in images that resists or eludes every effort to fix meaning through language’ (Reinhardt Citation2007, 25). As such, silence is a possible response to the encounter with an image; it should not be equated with passivity or lack of sensitivity. Some images do not operate on observers immediately but only with same distance or delay; others do operate immediately on observers, but observers may find it difficult to specify and articulate what these images do and how they do it.

In the two-way active mode of interaction, necessitating digital images, ‘the user looks at the image to begin the process of interpretation; however, she uses one or more of her other senses to modify the content and form and complete the process of interpretation’ (Bennett Citation2012, 63). Modifying images is easier today than ever before. Thus, users move from seeing to changing. Changes may include cropping or digitally altering images or highlighting what appears in a photograph’s background (which may tell a story other than that told by the central figures). Older images designated as representations of peace can be modernized and adapted. Black-and-white photographs can be colorized (or vice versa) to explore how change in color affects perception. Original images can be produced from scratch. All of this can be fun but in addition to fun it also helps students understand their individual relationships to images and how they see things.

In the three-way active mode of interaction, finally,

the user looks at the image to begin the process of interpretation, uses one or more of her other senses to access the information, modifies the content or form and either completes the process of interpretation or optionally shares it with others by redirecting distribution of the image to others (e.g. through social networking venues)

Thus, users progress from changing to sharing (see ):

Sharing images with others is an integral component of IPI: it reflects the basic operating procedures of digital images (see above) and opens a conversation about individual peace images and the producer’s conception(s) of peace. Such conversations must observe everything that has been said above about the viewing experience. They will never be only about images; they will also shed revelatory light on a person’s individual and collective identity which condition their conceptions of peace. In our course, for example, one of the students chose three images and altered them by cropping them and changing color saturation. She was interested in ‘how differently people react to the various versions of the images’ and hypothesized that the answer to this question would reflect ‘age, gender, and study field’ – a hypothesis partially confirmed in the study she conducted among her peers after sharing the altered images with them (Mikkonen Citation2019).

Some students will be more willing, and others will be less willing, to contribute to such an auto-ethnographic exercise, and no-one should be forced to reveal more of themselves than they want to. It is particularly important to free students from the fear of images, especially the fear that one’s image interpretation might be ‘wrong’. Images carry with them ‘excess meaning’ (MacDougall Citation1998, 68) that IPI acknowledges because it serves a conversation about images, cultures, politics, and peace. Some students, looking for assurance, may feel confused, at least initially; others will feel liberated from authoritative designations of meaning. Appreciating interpretive ambiguity is part of an interactive experience. It must be approached very carefully indeed as it challenges conventional habits of seeing and meaning making.

In our teaching experience we have learned that today many young people are very skilled image actors, very eager to engage with images, and ready to adapt to new challenges and unfamiliar instructions once encouraged to do so and liberated from the restrictions of a normal classroom scenario. Yet, students do not normally reflect upon what they are doing when they operate with visual images in their daily performances. Thus, interactive teaching begins with awareness-raising exercises so as to establish the basic operating procedures of visual images as outlined above.

3) New peace images

In addition to negative peace photographs, photojournalism conventionally documents formal peace negotiations, victory celebrations, and the signing of peace accords. Examples of such images can easily be found and problematized; they can be regarded and interpreted from different perspectives and temporalities. Meaning(s) assigned to images change(s); such changes can be identified through critical, discursive, interpretive interventions into meaning making processes, capitalizing on temporal distance. Such changes are always more than just changes in meaning; they always reflect wider political and cultural configurations which can be visually-discursively explored. More ambitiously, photographers can try to contribute to peace pro-actively (Allan Citation2010; Sliwinski Citation2011; Ritchin Citation2013), understanding peace as a visual subject in its own right, shaping understandings of peace among viewers beyond established ones and undermining the simple but often misleading war – peace binary. Problematically, peace becomes invisible the longer it persists; it is taken-for-granted, unquestioned and disqualified as subject of photojournalistic representation which emphasizes what is new, unusual, and unexpected, dangerous, dramatic, and unpredictable.

As part of our project Peace Videography, we invited young visual artists to make an image of peace. We locate IPI within the tradition in peace education of attempts to ‘imagine, invent, and create cultures of peace and build spaces for others to do so’ (Lehner Citation2021, 144) by means of artistic re-imagining, acknowledging that ‘[p]eace and peacebuilding are not just skills and knowledge, but also art, a creative process that originates in our imagination’ (Lehner Citation2021, 147; see also Lederach Citation2005).Footnote5 Indeed, ‘creative skill-building’ is seen in peace education as an important ingredient of ‘process oriented’ youth development – a ‘journey of learning, trying, thinking, failing, and succeeding’ (Jacobs Citation2008, 2) and, in IPI, of sharing artistic experience with others in interactive formats. Empowerment and community participation are among the objectives of many participatory photography projects involving young people (see Delgado Citation2015, 80–85). Such projects aim to improve both technical and creative skills among participants. As Carter and Benza Guerra (Citation2022) note with regard to performance art as part of peace education, the ‘ability to create is a core skill of making a means of bringing about peace where it has been lost as well as where peace needs to be built stronger for its durability’. This applies to theatre, dance, and performance just as it does to the visual arts including non-artistic and non-professional approaches to the visual, all understood here as creative, collective endeavors with which to generate counter-images – literally and figuratively – to the temporalities (Baker and Mavlian Citation2014), visualities (Mirzoeff Citation2011) and choreographies (Morris and Giersdorf Citation2016) of war and violence.

We provided very little in terms of instruction, thus ‘provid[ing] a framework that [did] not explicitly define a preferred outcome for what learners will think and do’ (Bajaj Citation2008, 4). We wanted the artists to illustrate their own visions of peace rather than visualizing ours and emphasized only a few things: we were interested neither in a standard photojournalistic approach depicting peace negatively nor in landscape images representing peace of mind; the participants’ peace image had to include a social, human component. The artists acknowledged that the task was interesting and challenging; most of them had not thought about visualizations of peace before (while one artist had participated in our course). The results were stunning, both visually and theoretically,Footnote6 contributing to the generation of a tentative typology of peace images (see above, ). This typology helps us guide our facilitation and our – and our students’ – analysis of images in the classroom. As such, we integrate our experience with one group of students (outside the classroom) into our work with another group of students (inside the classroom), capitalizing on synergy effects.

Table 1. Cumulative typology of peace images, incomplete © Frank Möller & Rasmus Bellmer.

We were impressed by the extent to which the artists engaged with rather sophisticated concepts such as interaction. Sheung Yiu and Samra Šabanović looked at and for images on the internet (mode 1), changed them by recontextualizing and assembling them in an original manner (mode 2) and shared them with others by publishing the resulting video on our website (mode 3). They produced a 22-minute video comprising of stock images from the internet and spoken commentary presenting established critiques of photojournalism and rethinking them in light of the specific conditions of the digital age. For example, in an age of facial recognition software, every image of human beings, regardless of the photographer’s intentions, can put the subjects depicted at risk. In the video, the relationship between text and image is not always obvious; the resulting tension makes viewers reflect upon the intricacies of the text – image relationship. Furthermore, Yiu and Šabanović show in their work that what you see in an image inevitably reflects, and makes you think about, who you are: the title of their work, Sarajevo Roses and Clouds of June, cannot be understood as intended by the artists without knowledge of the specific circumstances referenced in their work. In their voice-over, they explain:

Hong Kong artist Jennifer Lai’s work titled ‘The Truth is Out there’

consists of 240 photos of clouds spanning across two exhibition walls.

Upon a closer look, however, it was revealed that the clouds are tear gas

with their background edited out and replaced with the colour of the sky.

The number of the photos matched the number of tear gas that the police

reportedly deployed during the June-twelfth mass protest.

The idyllic photos conceal the police brutality inflicted on protesters,

but once you live through a conflict, the conflict follows you everywhere.

(…)

In the Bosnian capital Sarajevo, people commemorate the bloody civil war by

covering the scar left by explosives on concrete pavements with red candle wax.

The melted candle wax takes the shape of the wound,

forming abstract patterns all over the city.

The memorial is given a beautiful name: Sarajevo Roses.

Besides the obvious symbolism, when asked to imagine an image of peace,

we often envision a serene landscape or a picturesque sky;

some are reminded of their families, others of nature.

But in every image, the ghost of war and conflict still lingers.

Trauma does not just go away.

We all carry a community of photographs within us.

Every photograph I took and will take contains of a particular disaster.

Now in every cloud, I see the shape of tear gas;

in every roses, explosions; in every prairie, trenches;

in every ocean, the floating body of Hong Kong protesters in black

and in every family portrait taken at the seashore, Alan Kurdi, the drowned

three-year old Syrian boy washed ashore on his tumultuous boat ride to Europe.Footnote7

Our project, thus, helps participants to understand how the way they see and think peace is influenced by their individual cultural and visual socializations and how, in turn, they can influence these socializations by seeing and thinking peace differently. Yiu and Šabanović, for example, suggest understanding peace not in terms of absence of war but rather in terms of implausibility of war and ask if an image can ever embody that implausibility. That conflict follows them everywhere, and in every image, does not, however, exclude other interpretations of the same images by viewers who do not share the artists’ experience.

Ana Catarina Pinho, in a photograph and a 6-minute video, deconstructs archival photographs in search of new meanings thus treating archives as ‘structures of meaning in process’ (Roberts Citation2014, 114) that can be discursively reconstructed and reordered. In a series of eleven photographs, Shihab Chowdhury visualizes the temporalities of war and peace. He took pictures of ordinary people doing ordinary things in a community center in Finland. Such centers had originally been built at the end of the 19th/early 20th century as meeting places for workers. During the Finnish Civil War, however, they were often used for military purposes, in which function they have become ingrained in people’s memories. Only recently, local people rediscovered these centers as community centers, and this is what Chowdhury’s photography documents (see ), visually exemplifying the step from aftermath to peace as recommended in the literature (Möller Citation2017).

Figure 3. Shihab Chowdhury, Concert (from the series Between violence and peace #8) © Shihab Chowdhury.

In a painting simply titled Peace, Sebastian Schultz alludes to the fragility of everyday peace and, by implication, to the fragility of every kind of peace (see ). What, only moments ago, was a peaceful summer garden party (or so we suspect) has now morphed into something else. We, the painting’s viewers, do not know what caused the change of atmosphere; we do not know, either, how and if the conflict will be resolved. Inspired by Galtung’s work and social conflict theory, the artist (in written commentary) asks: ‘Can peace and conflict coexist simultaneously? Can social conflict play a role in establishing or maintaining peace? Are we currently experiencing peace? If so, what kind of peace?’ These questions are at the core of peace education, visual and otherwise.

Students aren’t artists but they are image makers all the same. Their situation is slightly different because students of peace and conflict research have a basic knowledge on peace theories and practices. Still, the variety of definitions of peace and the different socializations students bring with them imply that hugely different peace images will be produced (just as our artists produced different images in different media). In a hierarchy-free learning environment, educators are in no position to ‘correct’ the students’ peace imaginations.

Traditionally, ‘art worlds situated knowledge in the object and accustomed audiences to passivity – purportedly experiencing what the creator intended’ (Sutherland and Krzys Acord Citation2007, 127). Through interaction, students change from spectators to producers. By doing so, they do not only become more involved in the production process; their responsibility, too, increases – responsibility for the image and for the knowledge claims attached to this image. Becoming part of the process of knowledge production enables students to understand both the constructedness of all such processes and the contingency of the resulting knowledge claims (including their own). It also facilitates critical engagement with others’ knowledge claims and the processes through which such claims gain legitimacy. As IPI is an open-ended method, new peace images will travel among students and each student might adapt or further develop them, thus producing peace images that the original image’s producer can neither predict nor influence. Interaction includes a surprise element.

4) Scholarly accompaniment and analysis

Educators guide, structure, and accompany interactive teaching inspired and informed by both their earlier work experience and the existing literature. The issue here is one of acknowledgement rather than judgment – acknowledgement of the plurality of peace images reflecting the plurality of identities and socializations that the students inhabit. The issue here is also one of grasping that what an image seems to show changes in parallel with information about its context. A seemingly simple sentence such as ‘This is an image of peace’ demands contextualization and deconstruction of the process of coming into being of both the image and the subject depicted. For example, the peace dimension of Chowdhury’s work, showing people listening to a concert, becomes clear only when the historical conditions of the main subject of his photography – the community center – are shared with the viewers (which Chowdhury does in written commentary on the website).

We use the images to construct a typology of peace images. In the classroom, the typology structures the viewing experience, helps viewers navigate the huge number of images they are regularly exposed to, and helps them to see peace in unusual places. Indeed, peace images are everywhere but often we do not recognize them as images of peace. shows a cumulative and (necessarily) incomplete typology of peace images.

The above categories, presented in arbitrary order, do neither imply ranking nor claim completeness. Ultimately, there may be as many categories as there are images. In the teaching context, none of them is more important or more appropriate than are others because all of them help students to envision peace.

5) Critical assessment

Every approach to peace education requires self-reflection on the part of educators. Since the inception of photography, critics regularly complained that there are too many images. Frederick Douglass wrote already in the mid-19th century about the planet’s conversion into a ‘picture gallery’ (quoted in Rogers Citation2010, 11); Siegfried Kracauer, in 1927, linked what he called ‘the blizzard of photography’ to ‘indifference toward what the things mean’ (Kracauer and Levin Citation1993, 432); Sontag, writing in 2003, suggested a connection between hyper-saturation with images and neutralization of photography’s ‘moral force’ (Sontag Citation2003, 105). The reiteration of the quantity argument shows that there have always been more photographs than any individual could possibly regard, let alone analyze. Thus, using photography has always required – and will always require – choices. In the context of IPI, the capability of choosing the right image for teaching purposes must be acquired: some choices will turn out to be fruitful and inspiring whereas others will not. Using images in an IPI context requires spending some time with them. For many students, this may be unusual, given the very short attention span nowadays devoted to individual images in our rapid-pace consumer culture. IPI necessitates slow looking, recommended by Mieke Bal especially in connection with images of suffering (Bal Citation2007, 113–115). Every image demands time to see what there is to see, to change it, and to share it with others.

Because images are seductive and engaging (MacDougall Citation1998, 68) conversations about images can easily be initiated. Accepting their narrative plurality, which is at the core of IPI, implies loss of ‘control of meaning’ (MacDougall Citation1998, 68) on the part of the educator. Indeed, image interpretation in IPI does not require ‘professional mediation’ (MacDougall Citation1998, 68) aiming to reach consensus about what an image ‘really’ shows. Educators are supposed to be in an advantageous position vis-à-vis students as regards the knowledge they bring with them to the classroom, enabling them to establish with some degree of authority that things are so and not otherwise. Such knowledge does not really help them in IPI, save for the theoretical and conceptual background that helps them structure and facilitate classroom encounters with images. Instead, their authority emerges from their capability to arrange IPI as an interactive, non-hierarchic conversation among equals – from mediation to facilitation – and the courageous and unusual renunciation of claims to intellectual superiority. Educating without mediating between different positions in search of consensus and making value judgements about these positions reflects an approach to culture – and, by implication, to education – that operates ‘in a non-dominative way’ in ‘a space of multiple voices or forces’ (Couldry Citation2000, 4). This is easier said than done; preparing such a space is difficult and maintaining it is perhaps even more difficult. Non-dominative, interpretive openness can easily morph into indifference devoid of moral standards.

Perhaps the most difficult question in IPI is the question of how to deal with representations of violence in the context of peace education. What to some students appears as an image of peace, others may regard as a representation of violence evoking traumatic memories. What appears to be a peace image to some may seem trivial to others, disregarding or perhaps even despising their own experience of suffering. While these are difficult questions requiring sensitivity on the part of the educator, they are not fundamentally different from questions pertaining to visual representation in viewing situations outside the classroom. While IPI cannot be expected to answer all the questions that are controversially debated elsewhere (see Sontag Citation2003; Bal Citation2007; Reinhardt Citation2007; Rancière Citation2009; Grønstad and Gustafsson Citation2012; Möller Citation2013), it can be expected to be aware of these questions. It is here that the educator’s background knowledge is most important in integrating the viewing experience into a conversation about the larger political, social, and cultural patterns within which this experience takes place. In other words, students must be addressed as citizens.

Conclusion

Visual peace education is about images of peace and about the relationship between images and peace. This relationship is not fixed but varies over time and across actors. While IPI cannot answer all the questions raised in the beginning of this paper, it can be said with some degree of assurance that it contributes to self-reflection among students regarding their own habits of seeing and the conditions in which these habits came into being. What you see reflects who you are, what experiences (and memories of experiences) you carry with you and how you are socialized into a world that is increasingly shaped and dominated by visual images. By engaging in conversations about images and by becoming image producers themselves, students in IPI may learn to deal with images reflectively and responsibly and accept (or at least critically engage with) the plurality of meanings they and their fellow students legitimately assign to any given image. In IPI, images serve as vehicles by means of which students think about politics, culture, society, and peace and the subject positions conditioning each person’s performance within these wider cultural and political configurations. Finally, IPI counter-acts upon feelings of helplessness and hopelessness resulting from overwhelmingly negative media reports on current events and the focus on violence in large parts of the literature on the visual construction of reality. Even if peace is absent in fact, it is always present as a potentiality and this potentiality can be visualized.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the journal’s anonymous reviewers for lucid, thoughtful and constructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper and to Kone Foundation for financial support of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Frank Möller

Frank Möller is a Docent in Peace and Conflict Research at Tampere University and a Docent in Political Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. From 2020 to 2022, he was leader of the project ‘Peace Videography’ funded by Kone Foundation and project researcher at the Tampere Peace Research Institute, Tampere University.

Rasmus Bellmer

Frank Möller is a Docent in Peace and Conflict Research at Tampere University and a Docent in Political Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. From 2020 to 2022, he was leader of the project ‘Peace Videography’ funded by Kone Foundation and project researcher at the Tampere Peace Research Institute, Tampere University.

Rasmus Bellmer currently works for ifa – Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen as part of the zivik Funding Programme where he coordinates the Advisory Board to the German Government for Civilian Crisis Prevention and Peacebuilding. From 2020 to 2022, he worked as a project researcher in the “Peace Videography” research project funded by Kone Foundation and was affiliated with the Tampere Peace Research Institute, Tampere University, Finland.

Notes

1. We are grateful to one reviewer for suggesting this function of captions.

2. This can be done with recourse to such critical writings on photography as Sontag (Citation1979), Burgin (Citation1982), Shapiro (Citation1988), Tagg (Citation1988), Solomon-Godeau (Citation1991), Rosler (Citation2006), Mirzoeff (Citation2011).

3. ‘Paradoxes of Photography’, curated by Mika Elo, The Finnish Museum of Photography, 13 May − 28 August 2022 (italics added).

4. Useful critical introductions into current technologies of image making include Bridle (Citation2018), Zuboff (Citation2019), Fuller and Weizman (Citation2021), and Rauterberg (Citation2021).

5. For examples of ‘arts-based approaches in peace education,’ see Lehner (Citation2021, 157–158); for the role of music in peace education and peacebuilding, see Ubaldo and Hintjens (Citation2020) and Journal of Peace Education 13 (3), 2016; for the role of the arts in peacebuilding, see Mitchell et al. (Citation2020).

6. See https://www.imageandpeace.com.

7. Italics indicate a female voice, normal font a male voice. See Sheung Yiu and Samra Šabanović, Sarajevo Roses and Clouds of June, at https://www.imageandpeace.com/sarajevo-roses.

8. Fred Ritchin explains that digital ‘proactive photography might show the future … as a way of trying to prevent it from happening’ (Ritchin Citation2009, 149–150), an important argument with regard to organized violence and climate change. It can be turned pro-actively towards peace by envisioning peaceful relations at some point in the future (for example, a digitally fabricated image of a Russian and a Ukrainian leader shaking hands).

References

- Allan, Stuart. 2010. “Documenting War, Visualizing Peace: Towards Peace Photography.” In Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches, edited by I.S. Shaw, J. Lynch, and R.A. Hackett, 147–167. Sydney: University of Sidney Press.

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York: Zone Books.

- Bajaj, Monisha. 2008. “Introduction.” In Encyclopedia of Peace Education, edited by M. Bajaj, 1–11. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- Baker, Simon, and Shoair Mavlian, edited by. 2014. Conflict – Time – Photography. London: Tate Publishing.

- Bal, Mieke. 2007. “The Pain of Images.” In Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain, edited by M. Reinhardt, H. Edwards, and E. Duganne, 93–115. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bennett, Audrey. 2012. Engendering Interaction with Images. Bristol: Intellect.

- Berger, John. 2013. Understanding a Photograph. London: Penguin.

- Bleiker, Roland. 2015. “Pluralist Methods for Visual Global Politics.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 43 (3): 872–890. doi:10.1177/0305829815583084.

- Bridle, James. 2018. New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. London and Brooklyn: Verso.

- Brunet, François. 2019. The Birth of the Idea of Photography. Toronto: Ryerson Image Centre.

- Burgin, Victor, edited by. 1982. Thinking Photography. London: Macmillan.

- Callahan, William A. 2015. “The Visual Turn in IR: Documentary Filmmaking as a Critical Method.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 43 (3): 891–910. doi:10.1177/0305829815578767.

- Carter, Candice C., and Rodrigo Benza Guerra. 2022. “Introduction: Peacebuilding Through Performance Art as Education.” In Education for Peace Through Theatrical Arts: International Perspectives on Peacebuilding Instruction, edited by C.C. Carter and R. Benza Guerra. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003227380.

- Couldry, Nick. 2000. Inside Culture: Re-Imagining the Method of Cultural Studies. London: Sage.

- Delgado, Melvin. 2015. Urban Youth and Photovoice: Visual Ethnography in Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deuze, Mark. 2007. “Convergence Culture in the Creative Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 243–263. doi:10.1177/1367877907076793.

- Elkins, James. 2011. What Photography Is. London and New York: Routledge.

- Emerling, Jae. 2012. Photography: History and Theory. London and New York: Routledge.

- Favero, Paolo. 2013. “Getting Our Hands Dirty (Again): Interactive Documentaries and the Meaning of Images in the Digital Age.” Journal of Material Culture 18 (3): 259–277. doi:10.1177/1359183513492079.

- Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. 2021. Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. London and New York: Verso.

- Gilgen, Peter. 2003. “History After Film.” In Mapping Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Digital Age, edited by H.U. Gumbrecht and M. Marrinan, 53–62. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Grønstad, Asbjørn, and Henrik Gustafsson, edited by. 2012. Ethics and Images of Pain. New York and London: Routledge.

- Haagerup, Ulrich. 2019. “Academic Who Defined News Principles Says Journalists are Too Negative. Exclusive: Preoccupation with Conflict Fosters Insecurity, Populism and Trust Deficit, Says Johan Galtung.” In: The Guardian, 18 January (https://www.guardian.com/world/2019/jan/18/johan-galtung-news-principles-too-negative).

- Harman, Sophie. 2019. Seeing Politics: Film, Visual Method, and International Relations. Montreal: McGill Queens University Press.

- Hirsch, Marianne. 1997. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

- Jacobs, Adam. 2008. “Process Over Product: How Creative Youth Development Can Lead to Peace.” Afterschool Matters 29: 1–8.

- Kracauer, Siegfried., and T Y. Levin. 1993. “Photography.” Critical inquiry 19 (3): 421–436. doi:10.1086/448681.

- Lederach, John Paul. 2005. The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lehner, Daniela. 2021. “A Poiesis of Peace: Imagining, Inventing & Creating Cultures of Peace. The Qualities of the Artist for Peace Education.” Journal of Peace Education 18 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1080/17400201.2021.1927686.

- Lister, Martin. 2013. “Introduction.” In The Photographic Image in Digital Culture. Second Edition, edited by M. Lister, 1–21. London and New York: Routledge.

- MacDougall, David. 1998. Transcultural Cinema. Edited and with an Introduction by Lucien Taylor. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mikkonen, Sonja. 2019. “Reception Study on Visual Variations,” seminar paper, Tampere University.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2011. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Mitchell, Jolyon. 2020. “Peacebuilding Through the Visual Arts.” In Peacebuilding and the Arts, edited by J. Mitchell, G. Vincett, T. Hawksley, and H. Culbertson, 35–70. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mitchell, Jolyon, Giselle Vincett, Theodora Hawksley, and Hal Culbertson, edited by. 2020. Peacebuilding and the Arts. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Möller, Frank. 2013. Visual Peace: Images, Spectatorship and the Politics of Violence. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Möller, Frank. 2017. “From Aftermath to Peace: Reflections on a Photography of Peace.” Global Society 31 (3): 315–335. doi:10.1080/13600826.2016.1220926.

- Möller, Frank. 2019. Peace Photography. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Möller, Frank, Rasmus Bellmer, and Rune Saugmann. 2022. “Visual Appropriation: A Self-Reflexive Qualitative Method for Visual Analysis of the International.” International Political Sociology 16 (1). doi:10.1093/ips/olab029.

- Morris, Errol. 2014. Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography). New York: Penguin.

- Morris, Gay, and Jens Richard Giersdorf, edited by. 2016. Choreographies of 21st Century Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Paglen, Trevor 2016. Invisible Images Your Pictures are Looking at You. The New Inquiry. 8 December (https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you).

- Pylyshyn, Zenon W. 2006. Seeing and Visualizing: It’s Not What You Think. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press.

- Rancière, Jacques. 2009. The Emancipated Spectator. London and New York: Verso.

- Rauterberg, Hanno. 2021. Die Kunst der Zukunft: Über den Traum von der kreativen Maschine. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Reinhardt, Mark.2007Picturing Violence: Aesthetics and the Anxiety of CritiqueBeautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Painedited byIn M. Reinhardt and H. Edwards 13–36ChicagoThe University of Chicago Press

- Reinhardt, Mark. 2018. “Violence.” In Visual Global Politics, edited by R. Bleiker, 321–327. New York and London: Routledge.

- Richmond, Oliver. 2008. Peace in International Relations. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ritchin, Fred. 1999. In Our Own Image. New York: Aperture.

- Ritchin, Fred. 2009. After Photography. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Ritchin, Fred. 2013. Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen. New York: Aperture.

- Roberts, John. 2014. Photography and Its Violations. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rogers, Molly. 2010. Delia’s Tears: Race, Science, and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Rosler, Martha. 2006. Three Works. 2006 edition ed. Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

- Särmä, Saara. 2018. “Collaging Iranian Missiles: Digital Security Spectacles and Visual Online Parodies.” In Visual Security Studies: Sights and Spectacles of Insecurity and War, edited by J.A. Vuori and R. Saugmann Andersen, 114–130. London and New York: Routledge.

- Seidler, Lutz. 2020. Stern 111. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Shapiro, Michael J. 1988. The Politics of Representation: Writing Practices in Biography, Photography and Policy Analysis. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Sliwinski, Sharon. 2011. Human Rights in Camera. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 1991. Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sontag, Susan. 1979. On Photography. London: Penguin.

- Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Sutherland, Ian, and Sophia Krzys Acord. 2007. “Thinking with Art: From Situated Knowledge to Experiential Knowing.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 6 (2): 125–140. doi:10.1386/jvap.6.2.125_1.

- Tagg, John. 1988. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ubaldo, Rafiki, and Helen Hintjens, edited by. 2020. Music and Peacebuilding: African and Latin American Experiences. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Vastapuu, Leena. 2017. Hope is Not Gone Altogether: The Roles and Reintegration of Young Female War Veterans in Liberia. Turku: University of Turku.

- Weber, Cynthia. 2011. ‘I Am an American’: Filming the Fear of Difference. Bristol: Intellect.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books.