ABSTRACT

FRIENDS for Life is an anxiety prevention programme that integrates cognitive behavioural approach with social and emotional learning. The current study examines the effects of the FRIENDS for Life programme in a school environment, with outcomes focusing on anxiety and aggression. The theoretical basis for the joint prevention and intervention of anxiety and aggression is based on their frequent simultaneous occurrence. Four classes of 4th-grade students (N = 85) were randomly assigned two to intervention and two to a no-treatment control group in a randomized control study. We measured the total anxiety and components of anxiety and the total of aggression and components of aggression with AN – UD and AG-UD aggression scale at pre-, post-, half-year, one-year and one-year-and a half follow-up. The results were inconclusive with regard to the effectiveness of the programme. However, there is some indication of possible effects on the reduction of anxiety and aggression in the boys’ sub-sample. This was also the sub-sample that showed higher levels of anxiety and aggression at baseline, suggesting possible difference in the effectiveness of the programme. Proposals are made to replicate the study in a larger format.

Anxiety is, by definition a combination of cognitive (e.g., worries), physiological (e.g., nausea), emotional (e.g., fear) and behavioural (e.g., avoidance) responses (Silverman and Treffers, Citation2001). Anxiety is widespread in childhood and is part of everyday life. The problems begin when anxiety becomes persistent, frequent and severe enough to hinder a child in its everyday (Weems & Stickle, Citation2005). There is a documented increase in anxiety in Slovenia (Kozina, Citation2014) and abroad (Twenge, Citation2000) and strong indication for early intervention – the typical onset of higher anxiety levels is in childhood.

Figure 2. Comparative means plot for the intervention (males and females) and control groups across the time points – general anxiety

Figure 3. Comparative means plot for the intervention (males and females) and control groups across the time points – general aggression

Table 1. Repeated measures ANOVA for testing the differences in anxiety and the anxiety components

Table 2. Repeated measures ANOVA for testing the differences in aggression and the aggression components

The FRIENDS programme (Barrett, Citation2005) is a structured cognitive behavioural intervention programme based on social and emotional learning for children and adolescents. The FRIENDS programme is developmentally adaptive, i.e., its modules are adapted to the developmental period in which the participants find themselves. FRIENDS for Life module is designed to address anxiety in middle and late childhood. It is based on a model that deals with cognitive, physiological and behavioural processes involved in the development and maintenance of anxiety (Barrett, Citation2005). The decision to use the FRIENDS programme in the study was based on its well-documented effectiveness and long-term positive outcomes. It is the only anxiety prevention programme supported by the World Health Organization (WHO – World Healh Organization, Citation2004). Numerous studies from English-speaking and other countries support the programme’s positive effects on anxiety reduction (e.g.,Barrett et al., Citation2006; Essau et al., Citation2012; Pereira et al., Citation2014), which mainly report small to medium effect sizes (Ahlen et al., Citation2015; Higgins & O’Sullivan, Citation2015) in samples with universal prevention. The reported effect sizes are higher in samples with children-at-risk (effect size = 0.44) or those children that are already diagnosed with anxiety (effect size = 0.84) (Briesch et al., Citation2010). A more recent meta-analysis (Higgins & O’Sullivan, Citation2015) was carried out on the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programmes (Fun FRIENDS, FRIENDS for Life, My FRIENDS) using several criteria: (a) evaluation of the FRIENDS programme; (b) appropriate age (4–16 years); (c) outcome measures of anxiety; (d) universal school-based intervention; (e) the study is randomizedcontrol trial; (f) the study is published in English language peer-reviewed journal. Seven papers met the criteria. The main findings were that all studies reported lower anxiety levels in their intervention groups with effects size ranging from small to moderate.

While difficulties related to anxiety are one of the most common psychological problems in childhood and adolescence (Barrett & Farrell, Citation2009; Neil & Christensen, Citation2009) and have negative effects on development, learning and interpersonal relationships (Barrett et al., Citation2005; Kozina, Citation2015) similar negative outcomes can also be attributed to aggression (Flannery et al., Citation2007). In addition to the negative effects on the individual, aggressive behaviour disrupts learning and teaching processes in schools, affects the school climate and reduces learning outcomes (Brown et al., Citation2004; Hoy et al., Citation1998). Although aggression is a relatively stable trait that manifests itself through aggressive behaviour (Huesmann et al., Citation1984; Olweus, Citation1979), there are children in whom decrease in aggression is observed during the course of development. However, the longer the aggressive behaviour persists, the more difficult it is to change it (Connor, Citation2002). It is therefore essential to address the problem of aggressive behaviour in childhood.

The theoretical basis for joint prevention and intervention lies in the simultaneous occurrence of aggression and anxiety. In studies on both non-clinical samples (Tanaka et al., Citation2010) and clinical samples (Furr et al., Citation2009; Levy et al., Citation2007; Mullin & Hinshaw, Citation2007; Phillips & Giancola, Citation2008), increased aggression often coincides with increased anxiety (Delfos, Citation2004). This relationship is of great interest for research and at the same time opens up the possibility of addressing anxiety and aggression, together with the same prevention and intervention programmes. This is also interesting because programmes for anxiety reduction programmes are empirically supported to a larger scale, i.e., there is a larger number of proven effects, including long-term effects, compared to programmes for aggression prevention and reduction (Marcus, Citation2007).

Although most studies on the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme are concerned with prevention of anxiety, to our knowledge there are no studies to date that have tested the effectiveness of the aggression reduction of the FRIENDS programme in a school setting. However, these effects have been studied in Slovenia on a sample of pupils in the 8thgrade who used My FRIENDS (FRIENDS module for adolescents) programme. The results indicate the effectiveness of the My FRIENDS programme for anxiety and also a possible buffer effect on aggression (Kozina, Citation2018). Due to the promising results of the sample of the 8thgrade, we wanted to test the effectiveness also in the 4th grade in order to plan prevention as early as possible. In addition, the joint administration allows a more economical use of time in schools and has a more far-reaching effect. In a school environment, it is well accepted to use programmes which, due to time constraints, could aim at several outcomes.

For this reason, we decided to examine the possibility of using the anxiety reduction programme FRIENDS for Life to reduce the aggression of the pupils at the same time. In the study, we will compare the anxiety and aggression levels of the pupils (outcome variables) who participated in the FRIENDS for Life programme (intervention) with the control group before the intervention. We are also interested in the persistence of possible effects. Therefore, a number of follow-up studies will be included in the analyses: 6 months, 1 year and one and a half year follow-up. Due to the significant gender difference in anxiety (Feingold, Citation1994) and aggression (Bettencourt & Miller, Citation1996), we will also investigate the gender interaction effects.

Method

Participants

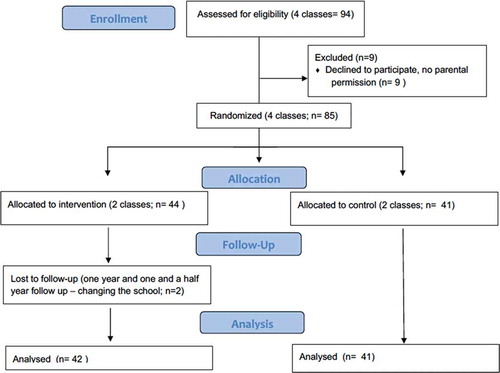

Fourth-grade students (aged 9–10 years) from two schools (convenience sample) in Slovenia were invited to participate in the study. In each school there were two classes of 4th-grade students; one of them was randomly selected (by draw by the fist author) into the intervention group and the other class into the no-treatment control group – a parallel randomized trial (). We have taken steps to assure that the intervention and control groups are as similar as possible in all relevant characteristics. Therefore, some of the variables of the participants were the same, i.e., the intervention groups and the control groups were from the same two schools (with the influence of school factors – e.g., school climate – on anxiety and aggression being controlled); on average, both groups were of the same age (between 9 and 10 years of age; the intervention groups and the control groups were at the same educational level, e.g., grade 4a and grade 4b); the gender ratio was sufficiently similar in both groups. A total of 44 students (24 girls and 20 boys) participated in the intervention group (group 1: 10 boys and 10 girls; group 2: 10 boys, 9 girls) and 41 (17 girls and 24 boys) in the control group (group 1: 11 boys and 9 girls; group 2: 9 boys and 13 girls). Another aim of the measurements carried out before the programme was to check whether the groups were sufficiently similar in both measured characteristics, i.e., anxiety and aggression (the so-called group equality test), in order to allow us to draw conclusions about the effect of the independent variables on the measured outcome.

Instruments

The AN-UD Anxiety Scale (Kozina, Citation2012) measures general anxiety and the three anxiety components with 14 self-report items: emotions – eight items (e.g., I suddenly feel scared and I don’t know why.), worries – three items (e.g., I am very worried about my marks.) and decisions – three items (e.g., I have difficulties making decisions.). Students indicate the frequency on the scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). The scores of components can be summed up to give an overall anxiety score. The herarhical three-factor structure was confirmed with the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on samples of students at primary and lower secondary level (RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.06; CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.95; TLI (Tucker Lewis Index) = 0.93; SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) = 0.033) and students in upper-secondary education (RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.04). The scale has proven to be psychometrically appropriate for the sample of lower secondary students (reliable: 0.70 < α > 0.84; sensitive: raverage = 0.60; valid:rANUD-STAI-X2Footnote1= 0.42) and upper-secondary students (reliable: 0.72 < α > 0.88; sensitive: raverage = 0.60).

The AG-UD aggression scale (Kozina, Citation2013) with 18 self-report items measures general aggression (composite scale of four components) and four components of aggression (physical, verbal, inner aggression and aggression towards authority) in the population of primary school students, students of lower secondary education and students in upper-secondary education. Students indicate the degree of their agreement with the following points: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral; 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree. The hierarchical four-factor structure was confirmed using the CFA on samples of primary/lower secondary students (RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90; SRMR = 0.05) and upper-secondary students (RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.88; SRMR = 0.05). In terms of function it measures reactive aggression and in terms of expression it measures direct aggression. The scale has proved to be psychometrically adequate in the sample of primary and lower secondary pupils (reliable: 0.72 < α > 0.84; sensitive: raverage = 0.56; valid: rAGUD – BDHIFootnote2= 0.69), and upper-secondary students (reliable: 0.70 < α > 0.80; sensitive: raverage = 0.43).

The FRIENDS programme (Barrett, Citation2005) consists of 10 workshops, which took place once a week (45 minutes each), two booster sessions and two parents meetings. The 45-minute time frame was used to test the feasibility of the programme for an educational environment where each lesson is 45 minutes. For the 4th-grade age group (9 to 10-year-olds), the programme The FRIENDS for Life was used. The content of the workshops includes: presentation of the programme and getting to know the group; feelings (understanding feelings in ourselves and others, developing empathy); body awareness and relaxation; self-talk (recognizing helpful and unhelpful self-talk); transforming unhelpful thoughts into helpful (powerful) ones; step-by-step problem-solving; role models and support networks; 5-step problem-solving plans; applying the skills in everyday life; a summary and a party.

Procedure

The parents of all participants gave a signed informed consent prior to the study as advised by the ethical guidelines of the Slovenian Psychological Society. The intervention group was then subjected to the FRIENDS for Life programme (10 sessions once a week + two booster sessions 1 month and 2 months after the end of the programme) which was conducted by the author of the manuscript (a researcher, psychologist). At the end of the programme, self-reported evaluation of anxiety and aggression was collected. Two parent meetings were organized and held – one at the beginning of the programme and one in the middle of the programme. A follow-up was planned after the intervention, 6 months after, year after, year and a half after the intervention. The periods of the follow-up studies were chosen taking into account the follow-up studies of other research in the field of anxiety prevention (Dadds et al., Citation1999).

Results

The effect of the programme was evaluated by analysing differences in the levels of degree of anxiety (AN-UD total score and components: worries, decision, emotions), aggression (AG-UD total score and components: physical, verbal, inner aggression, aggression towards authority) before and after the programme and in follow-up measurements (after, 6 months after, year after, year and a half after) compared to the control group. Repeated measure mixed ANOVA was employed as two independent groups (intervention and control) were subjected to repeated measurements over five points in time: before the intervention, after the intervention, a six month follow-up, a one year follow-up, a one and a half year follow-up. No significant differences in the degree of anxiety and aggression were found before intervention. Due to significant gender differences in anxiety and aggression, gender was used as an additional between-subject factor.

The time of measurement had a significant effect on general anxiety (η2 = 0.048) and on the components of anxiety: emotions (η2 = 0.070) and decisions (η2 = 0.130) (). The level of anxiety decreased from before the measurement to the follow-up in the control and the intervention groups. The only significant interaction effect (p < 0.10) is the effect of time of measurement, condition and gender on general anxiety (η2 = 0.026). Bonferroni post hoc tests comparing the level of general anxiety over different time points showed significant differences between the time before measurement and 6 months after measurement (mean difference = 3,555, p = 0.064) and between the time before measurement and a one year follow-up (mean difference = 3,461, p = 0.021). No other pairwise comparisons were significant. Using the comparative means plot, we can observe the decrease in anxiety from before to after and 6 months after the measurements. The decrease was slightly greater in intervention group compared to control groups and in boys sample compared to girls’ sample ().

The repeated measures ANOVA showed a statistically significant effect of the time of measurement on aggression towards authority (η2 = 0.029) and at a risk level of 10% also on general aggression (η2 = 0.026) and inner aggression (η2 = 0.020) (). We can observe the decrease in aggression from before the measurement to after the measurement in both groups, control and intervention and the subsequential increase in the intervention group, although not to the level before measurement. The gender effect is also evident, with the decrease being more pronounced in boys than in girls ().

Discussion

In the present study, we tested the effectiveness of the FRIENDS for Life programme (Barrett, Citation2005) for the prevention of anxiety and aggression in school setting. Due to the importance of early intervention and the onset of anxiety-related problems in childhood (Kessler et al., Citation2005), the programme was implemented in 4thgrade and in a universal setting.

Concerning anxiety, the results obtained were inconclusive regarding the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme in reducing anxiety (at the general anxiety level and at the component level). There was a significant interaction effect (time x condition x gender) on the general anxiety level. The decrease in general anxiety was observed in both groups, intervention and control. Nevertheless, it was somewhat stronger in the intervention group that had been subjected to the FRIENDS for Life programme, which might indicate the effectiveness of the programme in the boys’ samples compared to the samples of girls’.

The effect sizes are small with interaction effects (time x condition x gender) for general anxiety accounting for 2.6% of the variance, but they are consistent with similar studies that reported small to medium effect sizes at least at the universal level (Ahlen et al., Citation2015). The detected effects are more significant in samples with indicated and selective interventions (Briesch et al., Citation2010). Since this is a universal study, the lack of effects could be attributed to the selection of the sample, and possibly more significant effects could be detected when a more selective sample is selected (e.g., students with higher levels of anxiety and/or aggression). An indication for this assumption can also be obtained from our sample, where the most significant decrease in general levels of anxiety and general aggression is observed in the boys’ sample, the boys’ sample has at the same time reported higher levels of general anxiety and at baseline. Similarly, the results of the study conducted by Iizuka et al., (Citation2014)showed that the children that were most responsive to the effects of the FRIENDS for Life programme were the ones with higher initial levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties, indicated as at-risk children. This was also well documented in studies that investigated the aggression as an outcome measure (Spence et al., Citation2003; Stoolmiller et al., Citation2000). The Higgins and O’Sullivan (Citation2015)meta-analyses did not reveal gender effects, with one exception (Lock and Barrett, Citation2003) which reported significant gender effects, the effects were greater in for females compared to males. In our case, the opposite was true, but we must point out that in the study mentioned above, girls were the one who scored higher on baseline measurements of anxiety.

Interestingly, the results are also very similar for aggression. Although the results showed no significant interaction effect (time x condition x gender) for the general aggression or for its components, there was a significant time effect indicating a decrease in general aggression in both groups, intervention and control, and a larger decrease in the sample of boys compared to the sample of girls. In more detail, just as with anxiety the boys scored higher on general aggression than the girls on baseline. More precisely the data have showed a reduction in the boys’ aggression immediately after the end of the FRIENDS for Lifeprogramme, but in the follow-up measurement, the aggression increased again significantly, although not to the level of the pre-test. The effects – if they can be attributed to the effects of the FRIENDS for Life programme in the first place – are therefore short-lived. Overall, no significant impact of the FRIENDS for Life programme on the general aggression and aggression components of the students was found. In the meta-analyses of Higgins and O’Sullivan (Citation2015), the age proved to be a significant factor, with younger children showing effects immediately after the intervention, while older children showed the effects at follow-up measurements. This is consistent with our results, which showed only immediate effects. The complexity of the school environment and the factors influencing each student (at the school and class levels) are likely crucial.

Even if the results do not support the effectiveness of the FRIENDS for Life programme for anxiety and aggression prevention, we can see the similarities in the pattern that may reflect the joint prevention. This is the same small sub-sample, boys in the intervention group, who reported a decrease in the level of anxiety as well as aggression immediately after the FRIENDS for Life programme. This may indicate that some of the common characteristics of anxiety and aggression were addressed in the programme. However, this was not reflected in the overall sample and, more importantly, it has not persisted, and these need to be further investigated in additional, possibly larger, samples. The FRIENDS for Life programme includes activities that target several components that are primarily related to the development, maintenance and persistence of anxiety, but can also be associated with aggression. These components are emotions (attachment), physiological (body), cognitive (mind) and behaviour (learning) (Barrett, Citation2005). The emotions component refers to the importance of relationships, support groups, the importance of understanding the emotions of others and the self. The physiological component focuses on body signals, self-regulation and learning relaxation techniques. The cognitive component focuses on positive self-talk and the behavioural component on learning coping techniques step by step.

There are some limitations to the study that need to be considered. There are limitations in sample size and research design. The latter meets most of the criteria of quasi-experimental design, but not all criteria. The participants were not randomly selected from the population. It was also not possible to control all variables that influence the anxiety of students, e.g., personality traits, effects of the school environment, upbringing, etc. The sample size is small and not representative; therefore, the results are only preliminary and need to be repeated on a larger format. Another limitation is the use of self-report measures, a multi-method approach would be advisable in the future.

Even though our results are not so straightforward for us to make a recommendation for the further use of the FRIENDS for Life programme in Slovenia, early prevention and intervention and research on what works and what not is still highly supported. Of particular interest are the gender-specific effects, which require further research attention. As a final point, we would like to add that the prevention programmes can be implemented at a universal level (independent of the levels of anxiety or aggression) or at a selected level (only children with a higher level of anxiety and aggression are included in the programmes). There are many advantages of universal implementation, e.g., no stigmatization, avoidance of false-negative selections, but there are also disadvantages, which are that the intervention effects can be masked because the intervention has also been implemented in children who do not have problems related to anxiety or aggression (Barrett & Turner, Citation2001), which might be the case in our sample.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) would like to acknowledge also all the students participating in the study and in follow-ups as well as school coordinators that provided administrative support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 STAI-X2 = State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch & Lushene, Citation1970).

2 BDHI = Buss Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, Citation1957).

References

- Ahlen, J., Lenhard, F., & Ghaderi, A. (2015). Universal prevention for anxiety and depressive symptoms in children: A meta-analysis of randomised and cluster-randomised trials. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 36(6), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-015-0405-4

- Barrett, P. (2005). FRIENDS for life: Group leaders manual for children. Pathways Health and Research Centre.

- Barrett, P., & Turner, C. (2001). Prevention of anxiety symptoms in primary school children: Preliminary results from a universal school-based trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466501163887

- Barrett, P. M., & Farrell, L. (2009). Prevention of child and youth anxiety and anxiety disorders. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 497–512). Oxford University Press.

- Barrett, P. M., Farrell, L. J., Ollendick, T. H., & Dadds, M. (2006). Long-term outcomes of an Australian universal prevention trial of anxiety and depression symptoms in children and youth: An evaluation of the FRIENDS program. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_5

- Barrett, P. M., Lock, S., & Farrel, L. J. (2005). Developmental differences in universal preventive intervention for child anxiety. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(4), 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104505056317

- Bettencourt, B., & Miller, N. (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 119(3), 422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.422

- Briesch, A. M., Hagermoser Sanetti, L. M., & Briesch, J. M. (2010). Reducing the prevalence of anxiety in children and adolescents: An evaluation of the evidence base for the FRIENDS for Life program. School Mental Health, 2(4), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-010-9042-5

- Brown, K. M., Anfara, V. A., & Roney, K. (2004). Student achievement in high performing, suburban middle schools and low performing urban middle schools – Plausible explanations for the differences. Education and Urban Society, 36(4), 428–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124504263339

- Buss, A. H., & Durkee, A. (1957). An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(4), 343–349.

- Connor, D. F. (2002). Aggression and antisocial behaviour in children and adolescents. Research and treatment. Guilford Press.

- Dadds, M. R., Holland, D., Barrettt, P. M., Laurens, K. R., & Spence, S. (1999). Early intervention and prevention of anxiety disorders in children: Results at 2-years follow up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.145

- Delfos, M. F. (2004). Children and behavioural problems – Anxiety, aggression, depression and ADHD – A bio psychological model with guidelines for diagnostics and treatment. Jessica Kingsley.

- Essau, C. A., Conradt, J., Sasagawa, S., & Ollendick, T. H. (2012). Prevention of anxiety symptoms in children: Results from a universal school trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 450–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.003

- Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429

- Flannery, D. J., Vazsonyi, A. T., & Waldman, I. D. (2007). The Cambridge handbook of violent behaviour and aggression. Cambridge University Press.

- Furr, J. M., Tiwary, S., Suveg, C., & Kendall, P. C. (2009). Anxiety disorders in children in adolescents. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 636–656). Oxford University Press.

- Higgins, E., & O’Sullivan, S. (2015). “What Works”: Systematic review of the “FRIENDS for Life” programme as a universal school-based intervention programme for the prevention of child and youth anxiety. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(4), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1086977

- Hoy, W. K., Hannum, J., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (1998). Organisational climate and student achievement: A parsimonious and longitudinal view. Journal of School Leadership, 8(4), 336–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268469800800401

- Huesmann, L. R., Eron, L. D., Lefkowitz, M. M., & Walder, L. O. (1984). Stability of aggression over time and generations. Developmental Psychology, 20(6), 1120–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.20.6.1120

- Iizuka, C. A., Barrett, P. M., Gillies, R., Cook, C. R., & Marinovic, W. (2014). A combined intervention targeting both teachers’ and students’ social-emotional skills: Preliminary evaluation of students’ outcomes. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 24(2), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2014.12

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627.

- Kozina, A. (2012). The LAOM multidimensional anxiety scale for measuring anxiety in children and adolescents: Addressing the psychometric properties of the scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282911423362

- Kozina, A. (2013). The LA aggression scale for elementary school and upper secondary school students: Examination of psychometric properties of a new multidimensional measure of self–reported aggression. Psihologija, 46(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI130402003K

- Kozina, A. (2014). Developmental and time-related trends of anxiety from childhood to early adolescence: Two-wave cohort study. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11(5), 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2014.881284

- Kozina, A. (2015). Aggression in primary schools: The predictive power of the school and home environment. Educational Studies, 41(1–2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2014.955736

- Kozina, A. (2018). Can the “My FRIENDS” anxiety prevention programme also be used to prevent aggression? A six-month follow-up in a school. School Mental Health, 10(4), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9272-5

- Levy, K., Hunt, C., & Heriot, S. (2007). Treating co-morbid anxiety and aggression in children. Journal of American Academy for Children Adolescence Psychiatry, 46(9), 1111–1118. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e318074eb32

- Lock, S., & Barrett, P. M. (2003). A longitudinal study of developmental differences in universal preventive intervention for child anxiety.Behaviour Change, 20(4), 183–199.

- Marcus, R. F. (2007). Aggression and violence in adolescence. Cambridge.

- Mullin, B. C., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2007). Emotion regulation and externalising disorders in children and adolescents. In J. J. Gros (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 523–541). Guilford Press.

- Neil, A. L., & Christensen, H. (2009). Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.002

- Olweus, D. (1979). Stability of aggression patterns in males: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 86(4), 852–875. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.4.852

- Pereira, A. I., Marques, T., Russo, V., Barros, L., & Barrett, P. (2014). Effectiveness of the FRIENDS for life program in Portuguese schools: Study with a sample of highly anxious children. Psychology in the Schools, 51(6), 647–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21767

- Phillips, J. P., & Giancola, P. R. (2008). Experimentally induced anxiety attenuates alcohol related aggression in men. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.16.1.43

- Silvermann, W. K., & Treffers, P. D. A. (2001). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Research, assessment and intervention. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Spence, S. H., Sheffield, J. K., & Donovan, C. L. (2003). Preventing adolescent depression: An evaluation of the problem solving for life program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.3

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R. E., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1979). Manual for the state-trait inventory. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists.

- Stoolmiller, M., Eddy, J. M., & Reid, J. B. (2000). Detecting and describing preventive intervention effects in a universal school-based randomised trial targeting delinquent and violent behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.296

- Tanaka, A., Raishevich, N., & Scarpa, A. (2010). Family conflict and childhood aggression: The role of child anxiety. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(10), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509354516

- Twenge, J. M. (2000). The age of anxiety? Birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 1007–1021.

- Weems, C. F., & Stickle, T. R. (2005). Anxiety disorders in childhood: Casting a nomological net. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(2), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-4751–2

- WHO – World Healh Organization (2004). Prevention of mental disorders: Effective interventions and policy options. Geneva: World Health Organisation. http://FRIENDSrt.com/Content/Uploads/Documents/prevention_of_mental_disorders_sr.pdf.