ABSTRACT

In this paper we draw on the concept of fantasy and the principles of political discourse theory to develop an analytical framework for the study of Veja's anti-populist discourse. As one of Brazil's most influential publications in elite policy-making circles, Veja exerts considerable influence over the way populist politics is portrayed and understood. By tracking the signifiers ‘populism’ and ‘populist’ in the pages of this weekly magazine, our study affirms the distinctive virtues of adopting a psychoanalytically-informed perspective on political antagonism and ideology, treating fantasy as a core concept in the study of polarizing discourses generally and discourses about populism in particular. Far from remaining above the fray in its opposition to the discourses of both Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (and the Workers’ Party) and Jair Bolsonaro (and the Social Liberal Party), our critical fantasy study shows how Veja's pronouncements were both ideologically invested and normatively inflected.

Introduction

‘Following the backlash against left-wing populism from the Lula-Chavez era, it is now the right that needs, like celebrities harassed following a silly scandal, to reinvent itself’. It is in this way that in its 02/24/2021 edition (p. 53), one of Brazil's most influential news magazines – Veja – highlighted the need for a non-populist movement that, in accordance with ‘the rules of the establishment’, would be capable of appealing to those angry sections of the population that are still ‘attracted to right-wing populism’. The crucial question for the magazine was: ‘Who will speak to those sections of Brazilian society to whom Bolsonaro was able to connect during his 2018 election campaign?’ (ibid.). Thus, it was by denouncing the ‘evil’ of left-wing populism and the ‘inconvenience’ of right-wing populism that Veja offered its anti-populist assessment of the battered state of world politics at the dawn of 2021 (ibid.).

The opening anti-populist ‘horseshoe’ pronouncement by Veja appears to indicate a rather even-handed, negative evaluation of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and the Workers’ Party (PT) on the one hand, and Jair Bolsonaro and the Social Liberal Party (PSL) on the other hand, casting them both as a populist menace.Footnote1 As we will see, however, this apparent even-handedness is not so even-handed after all. A closer analysis reveals how Veja's responses to the populist politics of Lula and Bolsonaro from 2015 until 2018 let slip its ideological and normative masks, revealing how Veja's affectively-invested attacks on populism served primarily as a discursive device to advance its own agenda while presenting itself as ‘above the fray’.

In this paper, we put forward an argument against the horseshoe thesis in four steps. First, we situate our study of Veja's anti-populist discourse within the broader context of populism studies. Here, we foreground the value of discourse-theoretical approaches to populism studies on account of both their focus on discourses about populism, and the role they attribute to psychoanalysis – and to fantasy in particular – in helping us gasp the emotional, ideological, and normative significance of these discourses. Second, we sketch out the research strategy and methods underpinning our case study, proceeding thereafter to conduct a chronologically-driven fantasmatic analysis of Veja's anti-populist discourse. In the fourth and final step, we draw out in a more systematic way the implications of our analysis, including how it contributes to existing studies of discourses about populism. Focusing on the role played by Veja, we argue that a critical fantasy studies (CFS) approach to discourse analysis can help make more visible the ideological and normative significance of its anti-populist discourse and potentially, by extension, other anti-populist or antagonistic forms of discourse.

Populism studies, discourse theory, and critical fantasy studies

Populism studies includes the study of populist discourses and the study of discourses about populism. The lion share of populism studies thus far is devoted to the former, where the focus has been on how best to conceptualize and evaluate different kinds of populism. The need to pay attention to passion and emotion has also been emphasized in this enterprise, and there have been productive efforts to deploy concepts from psychoanalysis to think about the affectively charged nature of populist discourse (Eklundh, Citation2019; Glynos, Citation2021; Glynos & Voutyras, Citation2016; Ronderos, Citation2021; Stavrakakis, Citation2004; Zicman de Barros, Citation2020; Kinnvall & Svensson, Citation2022; Stavrakakis, Citation2021). However, it is the merit of political discourse theory (DT) to have introduced a perspectival shift within the general field of populism studies, pointing also to the importance of studying discourses about populism (De Cleen et al., Citation2018; Stavrakakis, Citation2017; Nikisianis et al., Citation2019; Ronderos & Zicman de Barros, Citation2020; Goyvaerts & De Cleen, Citation2020; De Cleen et al., Citation2021; Brown & Mondon, Citation2021). In this view, it is important not only to engage in efforts to refine our understanding of the concept of populism and associated phenomena from a theoretical perspective (i.e. how should populism be understood: as fundamentally economic, nationalist, illiberal, minimal, strategic, formal-discursive, ideological, legal etc.?) but also to point to what the signifier ‘populism’ does when it is articulated in politics, the media, and even in academia. The literature has clearly shown how discourses about populism can produce anti-populist positions as well as pro-populist positions, depending on the positive and negative connotations attached to the term (Stavrakakis, Citation2017; Goyvaerts & De Cleen, Citation2020; Brown & Mondon, Citation2021; Ronderos & Zicman de Barros, Citation2020; de Zicman de Barros et al., Citation2022). Treating populism as a signifier thus enables scholars to better foreground how actors and contexts frame and evaluate different aspects of populist phenomena, and with what affects and effects. It is notable, however, that the use of psychoanalysis to tackle broader questions of affective investment in discourses about populism, as well as its relation to the normative and ideological valence of those discourses, is still rather thin, despite the importance attributed to psychoanalysis by DT (cf. Glynos & Mondon, Citation2016). Indeed, while the important role the signifier ‘populism’ plays in the critical analysis of discourses about populism has rightly been the subject of much discussion and empirical exploration, the corresponding role fantasy can play remains noticeably underdeveloped. We thus take seriously the call from scholars in this field to better integrate psychoanalytic categories into discourse studies, partly as a way to better grasp and understand the affective investment present in often polarized discourses about populism (De Cleen et al., Citation2021; Glynos, Citation2021; Ronderos, Citation2021; Stavrakakis, Citation2004; Zicman de Barros, Citation2020). In sum, while it is crucial to take note of the different meanings that attach to populism our focus in this paper is less about what its meaning should be and more about how the shifts in meanings and their inconsistencies can reveal underlying (fantasmatic) patterns and investments.

As noted above, DT's reliance on psychoanalytically-informed perspectives on identity and subjectivity opens up a pathway for the critical study of discourse organized around fantasy and the desire it stages. Here, ‘the logic of fantasy names a narrative structure involving some reference to an idealised scenario promising an imaginary fullness or wholeness (the beatific side of fantasy) and, by implication, a disaster scenario (the horrific side of fantasy)’ (Glynos, Citation2008, p. 283). Both beatific and horrific dimensions of fantasy rely on key elements through which the subject interprets the limits it encouters as a loss of enjoyment and its potential future recovery, often dramatized with reference to figures such as the ‘villain’, the ‘hero’ and the ideals at stake. For example, the villain (eg., thief) might threaten (or steal) something important to us (our enjoyment, our way of life, whether moral, political, economic, sexual, etc.), often deriving (sometimes excessive) pleasure at our expense. Villains tend to be portrayed in negative aesthetic terms (ugly, horrible, dirty, undesirable, and so on).Footnote2 On the other hand, the hero who comes to our rescue acts as guarantor of our ideals. ‘Hero-guarantors’ are often constructed in opposition to the villain (or thief) and are portrayed in positive aesthetic terms (beautiful, pretty, clean, sexy, and so on).Footnote3 A critical fantasy study thus seeks to unpack the way subjects affectively (over-)invest in certain discursive elements, which are ultimately sustained by the desire to overcome a perceived lack of enjoyment.

In what follows we aim to show how such a fantasmatic analysis enables us to draw out the normative and ideological significance of Veja's discourse about populism. Our psychoanalytic perspective points to two things in particular. It points first to the ambiguity that attaches to loss. On one level this loss pertains to the (potential) loss of our way of life and its enjoyments, as threatened by a villain. But on another more disturbing level, the loss pertains to the (potential) loss of our bearings in a more general sense, foregrounding the idea of ‘ontological lack’, namely, that our way of life and its enjoyments are fundamentally contingent. This relativization of our enjoyment provokes an anxiety that we are tempted to flee from and it is this proximity to anxiety that accounts for the energy underpinning our ideological investment in those things that promise us protection from this anxiety. Second, psychoanalysis, allied to political discourse theory, points out how the threat of loss and its overcoming can be articulated in any number of ways and that these articulated contents are not innocent because they reflect very specific normative commitments. A critical study of discourse, informed by psychoanalysis, thus seeks to unpack the elements of fantasy in order to ascertain both the ideological and normative significance of political discourses, in this case Veja's anti-populist discourse.

Before presenting our fantasmatic narrative analysis of Veja's anti-populist discourse, however, we outline the research strategy and methods underlying our case study. In doing so we build on and extend literature that emphasizes the central role the media play in shaping the character, scope, and influence of discourses in the spheres of politics and academia, including discourses about populism (Goyvaerts & De Cleen, Citation2020; Carpentier & De Cleen, Citation2007; Carpentier, Citation2020).

Research strategy

Why Veja?

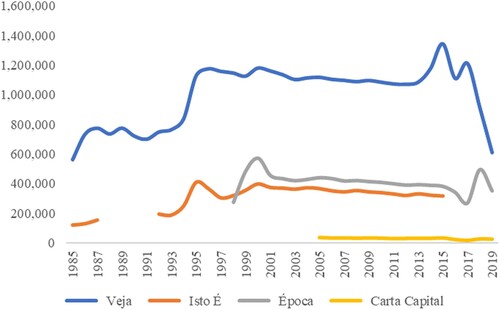

Although there is no doubt that the general public today reads fewer print newspapers and magazines, the traditional media's influence over policymakers, as well as financial and economic strategic players, continues to be considerable. This is how one should understand the significance attached to Veja as a weekly news magazine. Veja, since the 1980s, has targeted the Brazilian elite, aiming to exercise general influence over key decision-makers and discussion fora.Footnote4 Graph 1 plots the trends for Brazil's four news magazines with the highest circulation figures from 1985 to 2019. It shows that, although it targets an elite readership, Veja has managed, through a series of trickle-down effects, and within a highly concentrated media environment, to position itself as Brazil's most read news magazine.

Graph 1. Circulation 1985–2019. According to IVC Brasil, the figure for the reported ‘circulation’ of a publication is the gross number of printed copies. (IstoÉ magazine has not been affiliated to the IVC since mid-2015, for which there is therefore is no data from 2016 onwards.) While this is what appears on the graph, it is worth noting that this figure does not coincide with the number of copies that actually reach the hands of readers, whether through subscriptions, separate sales, targeted distribution, or indeed through shared use. Source: IVC – Circulation Verification Institute.

Of the four magazine weeklies, Veja is not only the most prominent in terms of distribution but also the oldest, being founded in 1968, followed by Isto É in 1976, Época in 1998, and Carta Capital in 1994. While both Isto É and Carta Capital came into being through the work of one of Veja's main founders, Mino Carta, Época was founded by the prominent multinational conglomerate Grupo Globo. Moreover, while Carta Capital is the only weekly that adopts a leftist editorial stance, Veja has the strongest appeal to the financial elites.

Interestingly, Veja's circulation attained historic peaks between 2014 and 2017, a period of intense social activity in which Dilma Rousseff's government and the PT influence over Brazilian politics was challenged. However, this feature of the graph is perhaps understandable given that Lula and the PT have been the magazine's favourite foes since the early 1980s, thus striking a chord with the rise of anti-PT sentiment from 2014 onwards. In this context it is worth noting that – buoyed by historically high approval ratings – president Lula served two consecutive terms (from 2003 to 2010), succeeded in 2011 by his chief-of-staff and party-political colleague Rousseff. However, though re-elected in 2014, Rousseff was impeached in 2016, accused of breaking the budgetary law, and Lula, the favourite in the 2018 presidential election, was cast as the mastermind of a nationwide corruption scandal and arrested on these grounds.

Mainstream media assumed a prominent role in laying the groundwork for public debate from 2014 to 2018 in the wake of the money laundering and political corruption scandal associated with Brazil's state-owned oil company Petrobras. Inspired by the Italian mani pulite (‘Clean Hands’) anti-corruption operation, and energized by the widespread mass-mobilisation protests across Brazil, the Lava Jato (‘Car Wash’) criminal investigation spear-headed by judge Sergio Moro forged a direct communication channel between his team and Brazil's media.Footnote5 Forging this alliance is now acknowledged to have been a key strategic move in winning over public opinion and taking down heavyweight public figures involved in corruption scandals. In particular, it facilitated the successful impeachment of Rousseff and the imprisonment of Lula (Almeida, Citation2019). However, on March 23, 2021, the Supreme Court (STF) deemed Lava Jato's prosecution of Lula to be biased, suspending Moro and overturning all charges against the PT leader. Lula subsequently challenged Bolsonaro successfully in the 2022 election, winning his third presidential mandate (2023–2026), while former judge Moro, having served as Bolsonaro's Justice Minister, was successful in securing a senate seat.

While the ubiquity of the signifiers ‘populis*’ have been evident in the Brazilian press since the early 1950s (Ronderos & Zicman de Barros, Citation2020; Zicman de Barros et al., Citation2022), with Lula receiving special attention from 2005 to 2010 (Pires & Castro, Citation2014), in this paper we follow these signifiers over the period 2015–2019 to generate a corpus with which to reconstruct the narrative presented in the pages of Veja in representing the more recent turns in Brazilian politics. In foregrounding the fantasmatic content and logic of its political commentary, and by implication the discourse of much mainstream discourse, we draw attention to how, from an elite policy-making perspective, Veja's anti-populism was not so evenly applied to Lula/PT and Bolsonaro/PSL, revealing its normative motivation and ideological investment.

Methods and sources

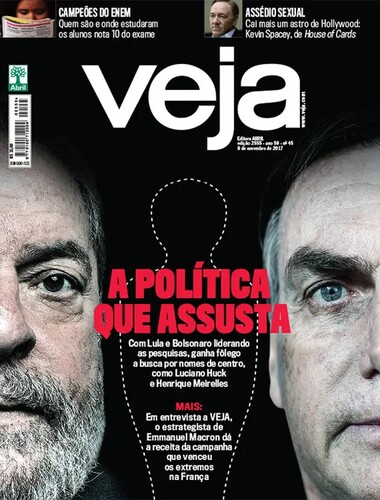

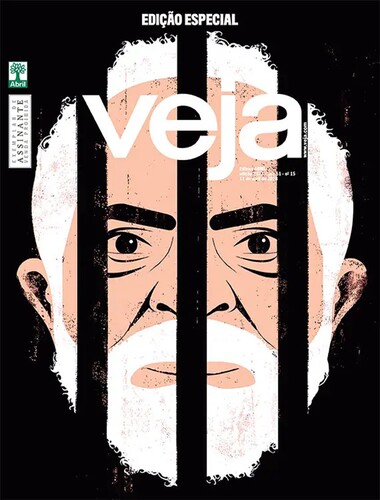

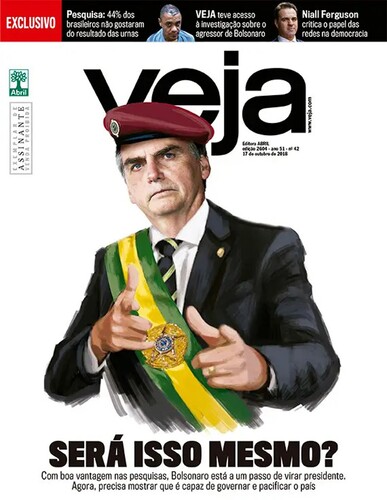

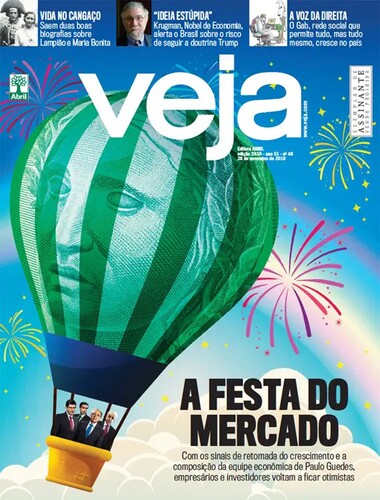

In constructing the narrative accompanying occurrences of ‘populis*’ through Veja's archives, we immersed ourselves in all relevant editorial and opinion content from the third quarter of 2015 to the end of 2018, comprising a database of 248 ‘populis*’ occurrencesFootnote6, amounting to 113 issues from 01/08/2015–31/12/2018. The key elements of fantasy outlined earlier provide a ‘macro-textual’ grammar with which to organize the material (Carpentier & De Cleen, Citation2007, p. 277). These include the villain, the hero, as well as the implied ideals and obstacles. But while such ‘macro-textual’ grammars tend to be used to facilitate text-based interpretations, we also analysed the magazine covers of Veja. More specifically, we included in our analysis the magazine covers that corresponded to issues with higher occurrences of ‘populis*’ because their images tended to dramatize in a particularly effective way the elements of fantasy, integrating the role of the villain and hero into the drama that structure our desires and enjoyments. In short, visual rhetoric, ‘with its layers, images, and … pervasive affectivity’ (Carpentier, Citation2020) offer a particularly apposite means of instantiating the ‘over-invested’ character of Veja's attachment to these figures. In what follows, therefore, we present a multi-modal analysis focusing on both text and image.

Constructing Veja's populis*-centric narrative

In order to help us better explore the normative and ideological significance of Veja's references to populism we need to first identify the key elements of fantasy. In this section, then, we aim to track the evolution of Veja's narrative by focusing on the villains and heroes in its storyline and the way they dramatize the ideals at stake and the obstacles that obstruct their realization. This section is divided into three parts. The first part focuses on Veja's anti-populist attack on Lula and his proxies, among them Rousseff and PT itself, covering the demonstrations leading to Rousseff's eventual impeachment (April 2015 to September 2016). The second focuses on Veja's anti-populist attack on both Lula and Bolsonaro, covering a period from the rise of Bolsonaro to Lula's imprisonment (April 2016 to April 2018). And the final part runs through the presidential campaign up to the election and its immediate aftermath (June 2018 to November 2018). Although the sequencing of the three sub-sections is chronological, it is important to point out that the description and analysis within each is thematic. The aim of this exercise is to draw attention to the highly charged character of its descriptions and images; to trace the meanings associated with the signifiers ‘populis*’; and to identify the fantasmatic elements of the narrative constructed by Veja (the villains, heroes, and ideals).

Veja attacks the populism of Lula

From mid-2015 to the dawn of 2016, Veja's storyline narrates a story of national crisis. Its narrative construction is propelled by growing anti-PT sentiment, enabling Veja's opposition to populism to assume a central role in explaining this period's social and political predicament. Depicting the populist villain (Lula, and Rousseff as proxy) as a parasitic, state-interventionist and corrupt political agent, Veja creates the space for a moral hero to emerge (judge Sergio Moro), capable of keeping the populist menace at bay. In what follows, we chart these discursive turns, paying special attention to the meanings attached to the signifiers ‘populis*’ and the affective investments in the characters – both villainous and heroic – constructed by Veja.

Seen as a ‘rickety’ political force in 1980 (23/01/1980, 27), PT was described in 2015 by Veja as the ‘Brazilian people's foremost enemy’ (12/08/2015a, p. 42 and 43), vividly portrayed under the cover headline ‘Brazil calls out for help’ (12/08/2015). Warning its readers about Rousseff's credibility deficit, Veja announced that the Lava Jato investigation would soon bring to light extraordinarily incriminating evidence, and pointed to ‘the beginning of the end of a cycle of populism and corruption that devastated Brazil’ (12/08/2015b, 51).

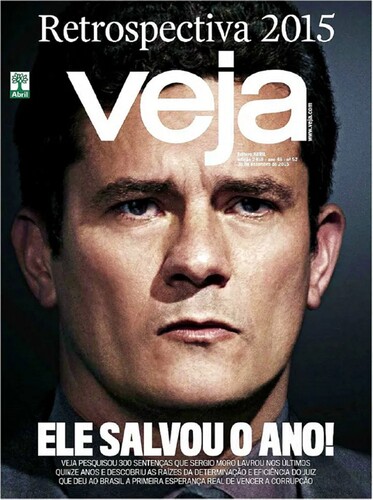

The Lava Jato investigative task force was based in Curitiba and headed by judge Sergio Moro. Its anti-corruption efforts had featured prominently in the press since March 17, 2014, with Moro being hailed as a ‘popstar’ and a ‘hero’ ever since (07/10/2015, 40). In a nine-page special report Veja paid tribute to Moro’s audacious crusade against corruption and crime, listing the 300 sentences that made this young judge a ‘national celebrity’ (30/12/2015, 50). In fact, the last printed edition of 2015 (30/12/2015) was dedicated to Moro under the hyped headline: ‘He saved the year!’ ().

Here it is crucial to note how the rhetorical reference to ‘populis*’ in Veja's pages often appeared in close proximity with the signifier ‘corrupt[ion]’. In so doing, the ‘populis*’ reference served as an indirect way of describing how the common wealth – embodied in the state-owned oil company Petrobras – was placed at the service of personal interests, enabling widespread, endemic corruption.

Corruption, however, quickly became synonymous also with public spending and state intervention more generally. In fact, like the oil industry, other segments of the energy sector were described as being exposed to the vagaries of state intervention, understood not as a means of correcting or softening the excesses of the market but as interference with the market, ushering in potentially tragic outcomes: ‘the populism of Dilma's government has disastrous consequences for the electricity sector and the consumer’ (10/02/2016, 78). Lula had based his ‘distributive populism’ on the commodity boom, but Rousseff would have to make use of different means to keep her ‘foolish [interventionist] measures’ afloat (03/02/2016, 10). According to the magazine, not only did these measures go against the laws governing the ‘creation of wealth’, but they proved that ‘populist regimes last only as long as other people's money’ (ibid.).

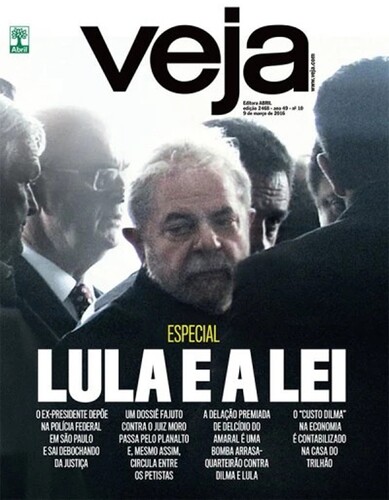

Under the headline ‘Lula and the law’, the special issue 09/03/2016 detailed the many scandals plaguing Lula, Rousseff and PT. The account, however, centred on Lava Jato's 24th phase, involving the so-called federal police operation Aletheia (a transliteration of the Greek word for ‘truth’ or ‘unconcealedness’), spearheaded by judge Moro and a 200-person strong force. It led to Lula being detained on March 4, 2016, at 8:40 am, taken from his home in São Bernardo do Campo to be questioned by the Federal Police in an effort to gather evidence of kickbacks and bribes channelled from inflated Petrobras contracts ().

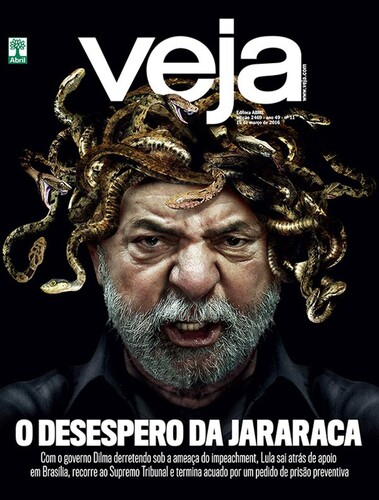

In a public speech, alluding to Moro's taskforce, Lula hit back, savaging the operation: ‘If they wanted to kill the jararaca [pit viper], they didn't hit the head but its tail’. Echoing Lula's defiant statements, Veja's 16/03/2016 issue ran with the headline ‘The desperation of the jararaca’, portraying Lula as an enraged, dangerous, and frantic Medusa figure (). In so doing, the magazine claimed that those who followed ‘simplistic and populist measures’ could only end up cornered by history's judgment (ibid., p.60).

For Veja, Lula's allegations were nothing but a populist sham, used in a despicable attempt to place himself above the law. Like other ‘populist experiences creating consumption bubbles’, PT's ‘disdain for the rich can only be explained by profound economic ignorance and unusual political autism’. Painting an unambiguously horrific fantasy scenario, Veja warned that if Lula were to prevail, the ‘social chaos [in Brazil] will be enormous’ (09/03/2016, 24). An opportunity to amplify this horrific dimension emerged soon enough, following the leaking by Moro of a ‘revealing’ phone call between Lula and Rousseff, which appeared to suggest that Lula would be appointed as the new chief of staff. The news had a striking impact and was splashed across Veja's pages. Alarming its readers with the significance of such a move by Rousseff's government, the magazine announced the regrettable beginning of ‘Lula's third presidential mandate’ (23/03/2016a, 49).

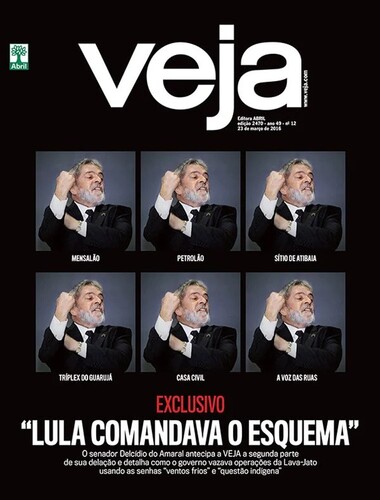

Lula's public reappearance signalled the comeback of ‘left populism’ and it could not but ‘awaken profound fears over the populist mismanagement of the public machine’. Strictly speaking, it is not the voice of Veja that should be heard but rather the ‘growing number of businessmen saying there is no way out for the economy with Rousseff in the Planalto [government palace]’ (23/03/2016b, 75). Rousseff's impeachment was thus necessary to stop the ‘return of populist politics’ (ibid, 76), awakened by Lula's desperate effort to re-enter the political fray (). In the end, Lula's nomination only lasted a couple of days, it being overturned by the Supreme Court (STF) on March 17, 2016. Worried entrepreneurs and economists now appeared in Veja's pages, claiming that ‘Rousseff is flirting with populism in order to survive’. As Rousseff's interventionism was disrupting the market, it was only through impeachment that the Brazilian economy could move forward (13/04/2016, 71–72).

Veja depicted the decline and fall of populist forces as the beginning of a new prosperous economic cycle, whose benefits would be seen in due course. ‘[P]opulism's impact on oil prices ruined the ethanol industry but now, without direct political interference at Petrobras, the sector is starting to rebuild itself’ (13/04/2016, 92). Such a principle was well-affirmed within financial sectors, leading brokers and investment firms to make deals to profit from Rousseff's downfall.

There is a direct dependence. The weaker Rousseff's government is, the more valuable Brazilian shares become, especially those in state-owned companies, as they are most affected by populist interventionism (20/04/2016, 67).

In a newly added special issue (20/04/2016), Veja celebrated the impeachment vote in the plenary session of the Chamber of Deputies. Rousseff was accused of breaking the budgetary law through so-called ‘tax pedaling’ and the process moved up to the Senate. Lacking the allies needed and losing the private sector's confidence, it was declared that ‘Dilma no longer commands Brazil’, expelling her from the game of politics for putting ‘populism and corruption at the centre of the nation's worries’ (07/09/2016, 49), and thus justifiably wiping her sinister smile from her face ().

The analysis above shows how the Brazilian ‘populis*’ villain, chiefly embodied by Lula's fearful figure (with Rousseff and the PT serving as proxies), embodied a parasitic and corrupt agent in Veja's narrative, the cause of social lack, draining economic wealth through state interventionism. We thus witness how Veja plays on a crucial ambiguity in the meaning that attaches to populism. While corruption appears at a frequent collocate of ‘populis*’, it is clear that it mobilizes the term in a way that targets public spending and state interventionism more generally. Elevating corruption as a key constituent of populism, however, makes it possible for a moral guarantor to appear in the heroic form of judge Moro, to challenge the corrupt populist villains of our common wealth (and our capacity to enjoy it). Veja portrays Moro as a stoic, handsome and tenacious saviour, a righter of wrongs, opposing widespread corruption and heroically defending the interests of the Brazilian people against the left-populist menace. Moreover, the highly charged character of the descriptions and images related to the construction of villains and hero through the signifiers ‘populis*’ is palpable. The affective over-investment in these signifiers and their associations with moral corruption and immature profligate spending of others’ money indicates that something more is at stake beyond a perceived threat to principles of free market economy, namely, an enjoyment linked to an ontology of lack (to be discussed further later). In what follows, we explore how the appearance of Jair Bolsonaro on the scene gives Veja the opportunity to affirm an anti-populist horseshoe hypothesis.

Veja attacks Lula and Bolsonaro (Veja affirms the horseshoe hypothesis)

In this subsection, our narrative construction draws on Veja's ‘populis*’ storyline following the impeachment process of Rousseff's government. At first it may appear surprising that Rousseff's impeachment sparks Veja's further preoccupation with, and discursive investment in, the signifiers ‘populis*’. With Lula remaining Brazil's most popular politician and favourite candidate for the 2018 election, it is nevertheless understandable that Veja's anti-populist anxiety remains high and even rises. Such concerns are turbocharged by the appearance of Bolsonaro on the political scene, depicted and constructed by Veja as yet another populist villain who places Brazil's economy at risk. As we will see, however, this anxious concern is appeased eventually by two developments: the appearance of a new heroic figure (Michel Temer) to act as guarantor of our way of life; and the much-anticipated imprisonment of Lula, Veja's main villain. In what follows, we highlight key strands of this storyline.

While Rousseff's impeachment seemed to offer grounds for optimism, political developments continued to upset the country's economic prospects, according to Veja. Not only was Lula's popularity still growing, making him the favourite candidate for the 2018 elections, but a right-wing populist rival had started to make advances in the electoral race:

The rise of populists and radicals in moments of crisis … is a classic tragedy in the history of democracies, and this could not be better represented than by the figure of Bolsonaro (20/04/2016, 67)

Bolsonaro's prospects were good given ‘the overwhelming fiscal imbalances bequeathed by Dilma Rousseff on account of populist spending sprees that drained public finances’ (15/03/2017, 61). The economic collapse caused by corrupt left-populist interventionism made right-wing protectionist populism appear preferable, thus sowing the seeds for an era of prolonged political polarization and social anger. According to Veja, if liberals were to blame for Bolsonaro's rise, it was only because they had not sufficiently challenged PT's radicalism from the outset (11/05/2016, 72).

Nevertheless, with Dilma's replacement by her vice-president, Michel Temer, a window of opportunity presented itself. Although ‘there is still a bit of populism in the air’, the investment prospects noticeably improved (15/03/2017, 62). Temer appeared to ‘distanc[e] himself from PT's radical agenda’, assuming a well-thought-out and steady reformist agenda, thereby emerging as the political guarantor of future market stability. In Temer's own words: ‘I want to go down in history as a reformist president … I am not a populist’ (15/03/2017, 65). As elections approached, Veja went on the offensive. To offset the very real populist danger of Lula's credible chance of winning the 2018 elections (19/07/2017, 67), demands for reform were made to bring fiscal order and prevent further chaos.

Without reforms, there will be no confidence in the economy, and public finances will fail, putting the state's own control apparatus at risk and making room for populist leaders who sell illusions (and benefits) in exchange for support. We already know how that all ends (12/07/2017, 56).

However, while the electoral campaign was in full swing, a special issue, which had been announced by Veja as early as 2014 (29/10/2014) was published (). On April 7, 2018, Lula was sentenced to prison for twelve years and one month. Veja gleefully presented some of the 144 issues dedicated entirely to denouncing Lula's anti-democratic tendencies (in about 6% of the overall number of issues, 11//04/2018b, 93–94). With Brazil's biggest populist out of the political arena, a ‘Trump-like figure with opposite ideological tendencies’, it was now time to think carefully about the political prospects for the upcoming elections (11/04/2018a, 59).

By following the signifiers ‘populis*’ we have identified the main elements of Veja's fantasmatic narrative of this period, supplementing our account with references to selected cover images that demonstrate the highly charged investment in key villains (Lula, Roussef, Bolsonaro) and hero-guarantors (Moro and Temer). Moral corruption and state interventionism remain central meanings associated with the signifiers ‘populis*’, employed as a means of elevating the market-rule principle and ideal in Veja's storyline. However, we have also seen how the attachment to this ideal was strengthened by the threat Bolsonaro posed, whose alleged interventionism rested less on redistributive than on protectionist mechanisms, thereby erecting a different set of political barriers to market dynamics.

Bolsonaro calls Veja’s bluff (Horseshoe hypothesis rejected)

Up to Lula's much-awaited imprisonment, the even-handedness of Veja's anti-populist discourse seemed consistent. However, Bolsonaro's explicit embrace of a reform agenda, including anti-protectionist free-market, anti-corruption and austerity measures, forced Veja to put its anti-leftist cards on the table. In other words, its normative commitments could no longer hide behind its anti-populism, which was now more clearly revealed to be a cover for its anti-leftism. As we will see Veja's moves were facilitated by turning to hero-guarantors, on both moral grounds (Moro) and economic grounds (Paulo Guedes). Suddenly and remarkably the threat of Bolsonaro's populism appeared to dissolve. In what follows, we chart some of these turns in Veja's storyline.

Already in August Bolsonaro was talking ‘about privatisation, even defending a social security reform agenda, to which he was opposed’ in earlier stages of the campaign (19/08/2018, 27). Originally sympathetic to trade protectionism and wary of foreign capital, Bolsonaro's economic stance had changed quickly under the guidance of his Chicago School economic adviser, Guedes, Bolsonaro's newly appointed future Minister of Finance.

With Lula playing an electoral role through his proxy candidate, and Bolsonaro's more orthodox market stance safeguarded by the economic guarantor, Paulo Guedes, Veja's reference to ‘populis*’ in characterizing Brazilian political actors dropped dramatically. Not only were there fewer references but they became somewhat circumstantial and vague. While the populist menace was still something to be resisted, the reformis*/populis* antagonism seemed far less important while Lula was ‘off stage’.

The solution to Brazil's problems is not simple, and the temptation of populist promises grows in the final stretch of campaigns. However, regardless of who wins, the next occupant of the Palacio do Planalto is expected to be responsible with the economy (17/10/2018, 47)

[Bolsonaro's] commitments to reduce the fiscal deficit and the public debt itself are hopeful, and explain the euphoric joy of the market in recent weeks given the growing chances that the right-wing candidate will receive the presidential sashFootnote7 (17/10/2018, 44)

The protectionist menace had dissolved amidst the country's newly ‘ultraliberal’ prospects, boosting the Real (Brazilian currency) and heralding a festive era for the Brazilian market (). And, as we will now see, with the dissolution of the protectionist threat the threat that Bolsonaro's populism represented was also decisively downgraded.

Already amidst Bolsonaro's victory, Veja struck a much more optimistic tone in offering its assessment of Brazil's political and economic prospects. It was keen to point out, for example, that while Bolsonaro's figure may ‘resemble that of Silvio Berlusconi, a right-wing populist’, the Italian and Brazilian conditions were completely different. This was because the mani pulite operation failed to punish corrupt politicians in Italy, allowing populist sentiments to fester and grow in strength (07/11/2018, 43).

However, not everything was different in the Italian and Brazilian cases. Just as the Italian prosecutor of mani pulite, Antonio di Pietro, entered politics, Moro now made a bold move (). With Moro as the new Justice Minister, ‘Bolsonaro formed an absolutely unique’ government by ‘betting on superministers’, bringing credibility to his anti-corruption mandate (07/11/2018, 47).

Unsurprisingly, it is at this point that we find the only positive valence accorded to the signifiers ‘populis*’ in Veja’s pages. In an interview with The New School professor James Miller, Veja produced a special article dedicated to populism. Under the headline ‘Light at the end of the tunnel’, the piece noted how populist actors could often invigorate liberal democracy (14/11/2018, 17–19). Thus we see not simply a shift of meanings associated with populism but also a shift in the valence attached to populism, as it becomes clear that certain forms of populism (pro-market, anti-leftist) are more tolerable than others, and even serve to re-invigorate democracy. Bolsonaro's dramatic shift on the economic front thus calls Veja's bluff, at least as regards its apparent horseshoe stance on populism, laying bare the affectively-endowed normative preferences underlying Veja’s anti-populist discourse.

On the ideological and normative significance of Veja's anti-populist discourse

So far, we have not simply drawn attention to the ubiquitous character of the words ‘populis*’ in the corpus of this study. In re-presenting Veja's narrative, we have also demonstrated the pivotal role these signifiers play in the construction of political antagonism. We did so by treating populism not so much as a frame of analysis but as an entry point (De Cleen & Glynos, Citation2021), following the ‘populis*’ signifiers as a means of unpacking the basic elements of its underlying fantasmatic narrative. In this final section we turn to the explanatory and critical implications of this analysis. We return to our theoretical discussions of fantasy to foreground the ideological and normative dimensions underlying Veja's anti-populist discourse and explain how we contribute to the debates around the critical study of discourses about populism. In particular, we argue that Veja's opposition to populism is driven by an ideologically invested normative commitment to an anti-leftist free market economy. By turning to the ideas of loss and lack, we foreground how these key references to ‘populis*’ fantasmatically inflect normative responses to perceived problems and invite distinctive forms of enjoyment that underpin its ideological investments.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, the figure of the villain in the narrative serves to do two things. First, it transforms ontological lack into an empirical loss. Second, it attributes blame for this loss (whether this loss is realized or threatened) to an ‘other’, conceptually embodied in the villain. In Veja's fantasmatic narrative, Lula serves as the prime embodiment of this horrifying ‘other’, giving Rousseff and PT a more subordinate status in constructing the villain. Moreover, Lula was described as a lazy worker attaining unearned political power, with Veja presenting him as an immoral thief of economic enjoyment who, in his depraved overspending state, would enjoy excessively at the expense of others:

He fits perfectly into the definition of bon-vivant: a person who does not work, living on privileges and perks … [N]ot being of rich origin, these types acquire access to luxuries through profitable contracts and by wielding power, but without subscribing to the values needed to distinguish the acceptable from the undesirable (26/04/2017, 63)

The construction of the villain in Veja's storyline depicts a parasitic agent feeding on the wealth (enjoyment) of others; an outsider who benefits, but does not create, the nation's wealth; someone who cannot tell the difference between right and wrong; and an operator who uses political mechanisms to interfere with the ‘proper’ way of organizing social life. In this way, Veja discursively places itself as part of an elite ‘above the fray’ by appealing to a technical, market-oriented expert knowledge that casts all political (populist) interventions as arbitrary and dangerous. It celebrates the (fantasmatic) ideal of a depoliticized consensus democracy undergirded by a dispassionate elitist expertise, even leading the magazine, at times, to question whether democracy itself might too precious to be left in the hands of lay voters (e.g. 20/07/2016, 73). This shows that Veja's narrative construction is not only invested in market economy principles but also in the idea that expert professionals can serve as guarantors of their realization. Veja not only defers to such expert knowledge, it also professes insight into what constitutes ‘proper’ enjoyment (as implied by the above reference to ‘bon vivant’), laying bare Veja's elitism and overall commitment to and investement in the status quo.

Against the background of Veja's elitist market-economic fantasy, PT's public spending and redistributive policy aims thus appeared to threaten in a fundamental way the normative interests the magazine represented. And yet, when Rousseff appointed the market-friendly Chicago school economist Joaquim Levy as finance minister in her second term, the magazine's anti-PT rhetoric appeared – if anything – to have been stepped up rather than softened, thus revealing Veja's highly invested anti-leftist stance. In other words, Veja opposed not just any form of public spending and state intervention but only those forms – however market-friendly – that decrease inequality and threatened the interest of the wealthy and the status quo more generally. Making corruption the central characteristic of populism through its discursive articulations enabled Veja's anti-left-populism to appear simply as anti-populism. In doing so, Veja presents public spending and state intervention as a form of corruption, carving out the space for an extra-economic moral guarantor to appear on the scene in order to rescue Brazil from this predicament, namely, Moro.

Initially, of course, Bolsonaro's protectionist plans also fitted Veja's populist corruption frame, thereby appearing to confirm the horseshoe hypothesis (that Veja would be equally opposed to left and right wing populism). However, as soon as Bolsonaro's rhetoric shifted, Veja let slip its ideologically-invested normative agenda. Despite Bolsonaro's equivalentially linked reactionary anti-elitist right-wing views regarding religion, gender, sexuality, and the nation, Veja came round to the view that he was not really a populist after all. Veja deployed its villain-and-hero macro-textual grammar and narrative, alongside highly charged image-based representations, to make the contrasts between left and right enjoyments accessible to its readership. First, Bolsonaro matched Veja's rhetoric that public meddling in the private sector (‘the market’) would only produce and exacerbate corruption, ushering in the prospect of the appointment of Moro as Justice Minister and moral guarantor. Second, the appointment of the pro-market Chicago-school economic conservative (Guedes) as his future Minister of Finance enabled the latter to play the role of economic guarantor of the nation's wealth.

While Veja's support for Bolsonaro effectively called its anti-populist bluff, unmasking its anti-leftist normative commitments, Veja's highly charged anti-populist rhetoric is equally revealing. In particular, it points to its ideological investment in this normative agenda. As we noted in our theoretical discussion earlier in the article, we can make sense of the over-invested (ie., ideological) character of its rhetoric if we see it as a means of coming to terms with ‘ontological lack’. From this point of view, Veja's extreme anti-populism serves as a way to avoid confronting the ineradicability of value-pluralism and the contingent character of identity construction. It is not just that Veja prefers anti-leftist forms of governance that protect the ‘natural’ market and status quo, it is also invested in the idea that this is the only rightful way of organizing the polity, as revealed by particular elite, financial-technocratic, experts. In this regard, it is worth drawing attention to how the profound enjoyment-euphoria brought about in the aftermath of the 2018 elections in Veja's storyline would eventually dissipate. Moro's figure crumbled () and Bolsonaro's market-liberal mask, embodied by Guedes, slipped (), registering the re-emergence of the spectre of populism.

We have thus argued that paying close attention to the constructions of fantasmatically invested villains and heros in Veja's narrative, help to make more visible the implicit normative and ideological aspects of its anti-populism. The elements and logic of fantasy help account not only for the affects linked to the way subjects are ‘gripped’ through enjoyment; but also the effects produced by these enjoyments, as they interact, reinforce, or contest wider discursive representations of social reality linked to norms, ideas and identities.

It is of course true that there is nothing intrinsic to the hero/villain narrative structure that predetermines its political expression as necessarily populist or indeed anti-populist. In other words, the link between hero/villain narrative structure on the one hand, and populist/anti-populist political expressions on the other hand, is contingent. And yet under some contextual conditions one of these polarized oppositions may resonate and reinforce the other. In this vein we have sought to unpack the underlying dynamics and contingencies underlying Veja’s anti-populist account of Brazilian politics, pointing, for example, to the metonymic transfer of a negative valence associated with the ‘threat of Lula’ to the ‘threat of populism’ to the ‘threat of Bolsonaro’. The contingency of these links is made visible in a number of ways, for example, by highlighting how the ‘threat of populism’ appears to evaporate suddenly with a shift in Bolsonaro’s expressed economic policy orientation.

Before we conclude it is worth highlighting how our argument resonates with, and contributes to, other key aspects of the scholarship on discourses about populism. As we noted early on in this paper, a growing number of scholars have rightly identified the need to unpack political, academic and journalistic discourses which make the signifiers ‘populis*’ central signifying references. Indeed, as we show elsewhere (Zicman de Barros et al., Citation2022), the signifying processes animating many populism discourses in Brazil have come about through the dynamic interaction of academic and non-academic discourses, by which we mean that the way concepts are academically defined can often shape the way lay actors speak about populismFootnote8, and vice versa. In some cases, scholars might be accorded greater authorative status, thus playing a key role in setting debates around populism in other spheres of discourse. In other cases, however, politicians might play a more prominent role in exerting influence over the dynamics animating populism discourses. In our case we have trained our attention on Veja, a particularly influential actor in the media sphere, whose pronouncements we critically examined to reveal important dynamics of the period at stake.

Our paper seeks to contribute to the literature on discourse about populism in another way too of course. The literature has rightly insisted that discourses about populism comprise not only anti-populist instances, but also pro-populist and non-populist instances, thus helping to reinforce the insight that contingency is the very condition through which the politics of discourses about populism get articulated. However, while these studies provide valuable insights in helping understand how populism is signified via antagonism and how it is integrated into broader social representations, accounts of why such discourses exert such ‘gripping’ appeal remain underdeveloped. In drawing on insights associated with psychoanalysis, the critical fantasy studies strand of discourse theory offers a means to grasp the affective dimension underlying political discourses, and thus help advance the study of discourses about populism, and antagonistic discourses more generally.

Conclusion

Despite Veja's apparently even-handed anti-populist stance targeting Lula and Bolsonaro, we argued that upon closer inspection, it turns out that Veja's anti-populism is actually an anti-left-populism. Treating Veja's anti-populism as a form of discourse about populism, we examined how the signifiers ‘populis*’ were articulated in Veja from the time the Petrobras scandal exploded in the media in 2015, which implicated Lula's PT, to Bolsonaro's victory in the Presidential elections of 2018. We deployed key concepts and principles of political discourse theory and critical fantasy studies in order to help make visible the way the signifier populism served as both cover and vehicle for its elite anti-leftism, pro-free-market normative messages. Moreover, we argued that the highly-charged character of its discourse betrayed an ideological investment that cannot be properly explained on normative grounds alone. The enjoyment evident in its attacks on Lula and PT were linked to an ontology of lack and its appearance as the possibility of loss – the loss of a way of life and the guarantees that support the status quo. Intimations of lack provoke anxiety because they point to the contingent character of social reality, including how there are different – more and less legitimate – ways of organizing the political economy of a polity. For Veja the signifier ‘populism’ marked a space in which this lack became articulated as an enjoyment whose loss was threatened by the populist agent qua villain. This articulation provoked an anxiety that prompted a powerful impulse to keep it at bay, reflected clearly in the way Veja's villains and heroes were affectively over-invested. By unpacking the fantasmatic elements that animated the drama of anti-populist discourse, our critical fantasy approach thus foregrounded the normative and ideological significance of Veja's anti-populist discourse.

By drawing on the concepts and principles of CFS and DT, and by applying it to the case of Veja we have sought to expand CFS and DT's field of application in the study of discourses about populism and polarized discourses more generally. While corpus linguistics facilitated the operationalization of our method of ‘following the signifier’ in the study of anti-populist discourse, we have shown how important it is to accompany this with thick qualitative description and interpretation, using both historical context and theoretical reflection as a way to make sense of the material. We suggest that a critical fantasy studies approach can advance the frontiers of political discourse theory by following the signifier ‘populism’ in order to go beyond populism. Treating populism as an entry point and ‘vanishing mediator’, rather than as a frame of analysis, enables us to use this approach to locate the source of ideological investments and the normative commitments for which populism serves as a vehicle.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sebastián Ronderos

Sebastián Ronderos teaches political theory and philosophy at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV/EAESP). He is also a research member of the DeSiRe research network (Democracy, Signification and Representation). His core research interests revolve around Latin American politics, populism, collective action, ideology and discourse analysis. His areas of expertise encompass Marxism, post-structuralism, Lacanian and post-Marxist discourse theory, and theories of democracy and ideology.

Jason Glynos

Jason Glynos teaches social and political theory at the Department of Government, University of Essex, where he is co-director of the Centre for Ideology and Discourse Analysis (cIDA) and Essex Chair of the DeSiRe network (Democracy, Signification and Representation). Through collaborative research projects he explores ways post-structuralist discourse theory and psychoanalysis can generate critical perspectives on topics related to alternative community economies, valuation practices, discourses about populism and democracy, and social science research methodology.

Notes

1 On 19 November 2019, months after winning the 2018 elections, Bolsonaro decides to part ways with the PSL, running for reelection in 2022 as a member of the Liberal Party (PL).

2 For other accounts of ‘theft of enjoyment’ see Žižek, Citation1989; Glynos, 2001.

3 For other accounts of the ‘guarantor’ see Chang & Glynos, Citation2011.

4 One such case was Veja's influence in constructing a business consensus over the need to impeach former president Fernando Collor de Mello in 1992 (see Chicarino et al., Citation2021).

5 Although the name Lava Jato (‘car wash’) derives from the way a petrol station in Brasilia was used to shift valuables of illicit origin, insofar as it is linked to the criminal investigation itself, it also suggests that Moro is engaged in a ‘cleaning’ exercise, aiming to rid the system of corporate and political corruption. A parallel can thus perhaps be drawn with Plato's pharmakon – as a name for both poison and cure.

6 The number of occurrences refers to the number of pages which include at least one reference to ‘populis*’.

7 The presidential sash is a decorative cross-body ornament, revered as a national symbol by the cultures that adopt it as a badge of the office of President of the Republic.

8 For instance, Veja’s treatment of populism as being largely ‘economic’ resonates with the Theory of Economic Populism (Aslanidis, Citation2022) while its Manichean, illiberal concepualization has roots often traced to modernization theory (Stavrakakis, Citation2017).

Bibliography

- Veja Archives (accessed 09 July 2021)

- Almeida, E. M. (2019). O papel do supremo tribunal federal no impeachment da presidente dilma rousseff. DESC-Direito, Economia e Sociedade Contemporânea, 2(1), 52–75. https://doi.org/10.33389/desc.v2n1.2019.p52-75

- Aslanidis, P. (2022). The Red herring of economic populism. In M. Oswald (Ed.), The palgrave handbook of populism (pp. 245–261). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, K., & Mondon, A. (2021). Populism, the media, and the mainstreaming of the far right: The Guardian ’s coverage of populism as a case study. Politics, 41(3), 279–295. http://doi.org/10.1177/0263395720955036

- Carpentier, N. (2020). Communicating academic knowledge beyond the written academic text: An auto-ethnographic analysis of the mirror palace of democracy installation experiment. International Journal of Communication, 14, 24. https://doi.org/10.46300/9107.2020.14.5

- Carpentier, N., & De Cleen, B. (2007). Bringing discourse theory into media studies: The applicability of discourse theoretical analysis (DTA) for the study of media practises and discourses. Journal of Language and Politics, 6(2), 265–293. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.6.2.08car

- Chang, W. Y., & Glynos, J. (2011). Ideology and politics in the popular press: The case of the 2009 UK MPs’ expenses scandal. In Lincoln Dahlberg & Sean Phelan (Eds.), Discourse theory and critical media politics (pp. 106–127). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chicarino, T. S., Segurado, R., & Ronderos, S. (2021). Impeachment! Em nome do povo: Uma análise discursiva da revista veja nos governos collor e rousseff. Mediapolis–Revista de Comunicação, Jornalismo e Espaço Público, 12(12), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-6019_12_8

- De Cleen, B., & Glynos, J. (2021). Beyond populism studies. Journal of Language and Politics, 20(1), 178–195. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.20044.dec

- De Cleen, B., Glynos, J., & Mondon, A. (2018). Critical research on populism: Nine rules of engagement. Organisation, 25(5), 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418768053

- De Cleen, B., Goyvaerts, J., Carpentier, N., Glynos, J., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2021). Moving discourse theory forward: A five-track proposal for future research. Journal of Language and Politics, 20(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.20076.dec

- Eklundh, E. (2019). Emotions, protest, democracy: Collective identities in contemporary Spain. Routledge.

- Glynos, J. (2008). Ideological fantasy at work. Journal of Political Ideologies, 13(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569310802376961

- Glynos, J. (2021). Critical fantasy studies. Journal of Language and Politics, 20(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.20052.gly

- Glynos, J., & Mondon, A. (2016). The political logic of populist hype: The case of right-wing populism’s ‘Meteoric Rise’and its relation to the status quo’. POPULISMUS Working Paper Series, 1–23. http://www.populismus.gr/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/WP4-glynos-mondon-final-upload.pdf (accessed 08 december 2022).

- Glynos, J., & Voutyras, S. (2016). Ideology as blocked mourning: Greek national identity in times of economic crisis and austerity. Journal of Political Ideologies, 21(3), 201–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2016.1207300

- Goyvaerts, J., & De Cleen, B. (2020). Media, anti-populist discourse and the dynamics of the populism debate. In B. Krämer & C. Holtz-Bacha (Eds.), Perspectives on Populism and the Media (pp. 83–108). Nomos, Baden-Baden.

- Kinnvall, C., & Svensson, T. (2022). Exploring the populist ‘mind’: Anxiety, fantasy, and everyday populism. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 24(3), 526–542. http://doi.org/10.1177/13691481221075925

- Nikisianis, N., Siomos, T., Stavrakakis, Y., Markou, G., & Dimitroulia, T. (2019). Populism versus anti-populism in the Greek press: Post-structuralist discourse theory meets corpus linguistics. In T. Marttila (Ed.), Discourse, culture and organization (pp. 267–295). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pires, T., & Castro, M. (2014). Lulismo: Entre o popular e o populismo. Revista Contracampo, 30(30), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v0i30.683

- Ronderos, S. (2021). Hysteria in the squares: Approaching populism from a perspective of desire. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 26(1), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41282-020-00189-y

- Ronderos, S., & Zicman de Barros, T. (2020). Populismo e antipopulismo na política brasileira: Massas, Lógicas Políticas e Significantes em Disputa. Aurora. Revista de Arte, Mídia e Política, 12(36), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.23925/v12n36_dossie2

- Stavrakakis, Y. (2004). Antinomies of formalism: Laclau's theory of populism and the lessons from religious populism in Greece. Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(3), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356931042000263519

- Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). How did ‘Populism’ become a pejorative concept? And why is this important today? A genealogy of double hermeneutics. POPULISMUS working paper 6. www.populismus.gr/wpcontent/uploads/2017/04/stavrakakis-populismus-wp-6-upload.pdf (accessed 8 December 2022).

- Stavrakakis, Y. (2021). Freud’s mass psychology today: Psychoanalysis, politics and populism in the age of post-truth. In A. Miller (Ed.), Psychoanalytische perspectives (Vol. 39, pp. 555–576). https://www.psychoanalytischeperspectieven.be/vol-39-3-2021/freuds-mass-psychology-today-psychoanalysispolitics-and-populism-in-the-age-of-post-truth (accessed 08 December, 2022).

- Veja. (02/03/2016). ‘O dinheiro dos outros’, Veja, pag. 10, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2463?page = 10§ion = 1

- Veja. (07/09/2016). ‘O Pecado Original’, Pereira, Daniel & Bronzatto, p. 49, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2494?page = 48§ion = 1

- Veja. (07/10/2015). ‘Moro, pop star’, Veja, p. 40, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2446?page = 40§ion = 1

- Veja. (07/11/2018). ‘Triplo cardapio’, Borges, Laryssa, p. 45, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2607?page = 44§ion = 1

- Veja. (09/03/2016). ‘Sem espaco para guinada’, da Nobrega, Mailson, p. 24, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2468?page = 24§ion = 1

- Veja. (10/02/2016). ‘No limite da imprudencia’, Alvarenga, Bianca, p. 78, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2464?page = 78§ion = 1

- Veja. (11/04/2018a). ‘Ele não e o primeiro’, Teixeira, Duda, p. 59, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2577?page = 60§ion = 1

- Veja. (11/04/2018b). ‘Vies autoritario’, Bronzatto, Thiago, p. 93-95, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2577?page = 72§ion = 1

- Veja. (11/05/2016). ‘Quem criou Bolsonaro’, Wolf, Eduardo, p. 72, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2477?page = 72§ion = 1

- Veja. (12/07/2017). ‘Não pedale, Meirelles’, Sakate, Marcelo, p. 56, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2538?page = 56§ion = 1

- Veja. (12/08/2015a). ‘O Brasil perde a calma’, Veja, p. 42-43 https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2438?page = 42§ion = 1&word = 2438

- Veja. (12/08/2015b). ‘O fim da farsa’, Veja, p. 51, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2438?page = 50§ion = 1&word = 2438

- Veja. (12/09/2017). ‘Da para ser optimista’, Padua, Luciano, p. 72-73, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2547?page = 72§ion = 1

- Veja. (13/04/2016). ‘O governo repete seus erros’, Sakate, Marcelo, p. 70-72, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2473?page = 70§ion = 1

- Veja. (14/11/2018). ‘Luz no fim do tunel’, Paduani, Roberta and Miller, James, p. 17-19, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2608?page = 17§ion = 1&word = James

- Veja. (15/03/2017). ‘Temer, o reformista’, Junior, Policarpo, p.65, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2521?page = 64§ion = 1

- Veja. (15/03/2017). ‘Um sinal de luz’, Alvarenga, Bianca, p. 61, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2521?page = 60§ion = 1

- Veja. (16/03/2016). ‘Macri tem pressa’, Guandalini, Giuliano, p. 60 https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2469?page = 60§ion = 1

- Veja. (17/10/2018). ‘Da para cumprir?’, Alvarenga, Bianca, p. 47, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2604?page = 46§ion = 1

- Veja. (19/07/2017). ‘Eles não estão nem ai’, Guandalini, Giuliano, p. 67, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2539?page = 66§ion = 1

- Veja. (19/08/2018). ‘a ameaça e real’, Veja, p. 27, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2593?page = 36§ion = 1

- Veja. (20/04/2016). ‘Fazendo historia’, Bronzatto, Thiago, p. 67, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2474?page = 67§ion = 1

- Veja. (20/07/2016). ‘‘‘nos’’ contra ‘‘eles’’’, Gryzinski, Vilma, p.73, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2487?page = 73§ion = 1

- Veja. (22/06/2016). ‘Uma safra de retomadas nas usinas’, Sakate, Marcelo, p. 92, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2483?page = 92§ion = 1

- Veja. (23/01/1980). ‘Longe da praia’, Veja, p. 27, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/594?page = 26

- Veja. (23/03/2016a). ‘A exploacao da crise’, Veja, p. 49, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2470?page = 48§ion = 1

- Veja. (23/03/2016b). ‘A economia a deriva’, Sakate, Marcelo, p. 74, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2470?page = 74§ion = 1

- Veja. (24/02/2021). ‘A direita pos-Trump’, Veja, 24 February 2021, p. 53. https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/186694?page = 52§ion = 1

- Veja. (26/04/2017). ‘Gato por lebre’, Kramer, Dora, p. 63, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2527?page = 63§ion = 1

- Veja. (28/12/2016). ‘A revolta nas urnas’, Veja, p.67, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2510?page = 66§ion = 1

- Veja. (29/10/2014). ‘Eles sabiam de tudo’, Veja, p. 1, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2397?page = 1§ion = 1

- Veja. (30/10/2015). ‘As trevas contra a luz’, Veja, p. 85, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2458?page = 84§ion = 1

- Veja. (30/12/2015). ‘A cabeça de Moro’, Petry, Andre, p. 50, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2458?page = 50§ion = 1

- Veja. (31/10/2018). ‘Há um risco claro’, Costa, A.C., p. 46, https://veja.abril.com.br/acervo/#/edition/2606?page = 46§ion = 1

- Zicman de Barros, T. (2020). Desire and collective identities: Decomposing Ernesto Laclau's notion of demand. Constellations, (4). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12490

- Zicman Barros, T., Glynos, J., & Ronderos, S. (2022). Populism in the making: A multi-sited discursive approach to Brazil’s fourth republican period (1946–1964). POPULISMUS Working Papers No. 15. http://www.populismus.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/wp-15-upload8.pdf (accessed December 2022)

- Žižek, S. (1989). The sublime object of ideology. Verso.