ABSTRACT

Michele Placido’s Pummarò (1990) and Carmine Amoroso’s Cover Boy (2006) bring the legal, economic, and social precarity of West African and East European migrants in Italy to the screen. This article examines, firstly, how subjects who come from the Global South, or who are marked as such, are framed in their precarity from a Eurocentric perspective and, secondly, how they exercise agency and break free of the colonial, racializing, gender-critical, or classist frames imposed on them. The ‘illegitimate art’ of photography is suited to reflect this two-sided process of precarization and empowerment because it is accessible to diverse social classes. This heterogeneous plurality that produces, mediates, and receives photographs also determines an intersection of gazes that emerge from divergent positionings before and behind the camera. To bridge professional with amateur approaches, my performative analysis combines Philippe Dubois’ artistic concept of the ‘photographic act’ with Ariella Azoulay’s critique to reconsider the contingent and civil potentiality of photography by reimagining the ‘event of photography’. A media-critical relation between photography and film ultimately reveals this interplay of gazes to be a meta-aesthetic gesture by the observing medium of film, which self-critically interrogates its own cinematographic modes of representing precarious subjects.

‘In someone else’s hands’: Pummarò (Citation1990) and Cover Boy (Citation2006)

By focusing on different geographic and temporal contexts, Michele Placido’s Pummarò (Citation1990) and Carmine Amoroso’s Cover Boy (Citation2006) reflect on two key aspects of mass immigration to Italy since the 1990s: Pummarò on migration from North and West Africa, Cover Boy on migration from Romania and Albania after the collapse of the Soviet Union (cf. Di Muzio Citation2012). Although a legal framework that permitted immigration to Italy from the Global SouthFootnote1 was created during this period by the Martelli Law (1990), after Silvio Berlusconi’s centre-right coalition came to power in 2001, the harsh Bossi-Fini Law (2002) reinforced a policy of ‘white continentalism’ (O’Healy Citation2019, 79). Looking further back in history, in Italy’s case the political goal of a homogenisation that protects a ‘Northern’ race from a ‘Southern’ one (Lombardi-Diop and Romeo Citation2016, 370) was not just linked to colonisation in East and North Africa (Eritrea, Somalia, parts of Libya, Ethiopia) as Southeastern Europe (the Dodecanese Islands; Albania). By the beginning of the 19th century, anti-Southern theories served to construct a White Italian race that was problematically interwoven into Italy’s founding process as a nation-state in 1861. This enshrined Southern Italians’ subaltern status relative to their Northern compatriots (ibid., 368–370). Compared with France and the UK, Italy still appears to be struggling to confront its colonial legacy, since – in large part due to the exclusionary policies that have dominated in Italy since the 1980s (ibid., 374) – there has been no ‘bottom-up’ process of decolonisation.

Pummarò and Cover Boy are situated within this conflict-driven context. Like many other films about migration set in Italy, they create a narrative of precarity that is materially framed by one or more of the following: illegal or time-limited immigration, having either forged visas or none at all, legally insecure, physically dangerous and desperately underpaid casual work with neocolonialist overtones, and racist othering and social exclusion. Pummarò’s frame story concerns the fate of Giobbe Kwala Toré from Ghana, pejoratively known as Pummarò, who as a Black tomato picker working in the Southern Italian hinterland has been ruthlessly exploited by the local mafia. He suddenly turns against them, and flees with a revolver and truck stolen from the mafia boss. As a result, his planned meeting with his younger brother Kwaku Toré, who is hoping Giobbe can help him with money for his studies, is postponed until the end of the film. In the main story, Kwaku (played by the professional drummer Thywill Abraham K. Amenya) follows his brother’s trail to Frankfurt. After facing significant discrimination, he and Giobbe’s pregnant girlfriend Nanou find Giobbe dead, the victim of a knife attack. Cover Boy, meanwhile, focuses on the fate of the Romanian car mechanic Ioan, who as a child witnessed his father being shot in the street during the turmoil of the Romanian Revolution. Years later, in search of a better future, Ioan (played by the performer and choreographer Eduard Gabia) secures a three-month visa to ItalyFootnote2 and moves to Rome. There, he befriends Michele, whose employment has been precarious for many years due to his Southern Italian background and who conceals his homosexuality from Ioan. Together, they attempt to overcome their shared precarity, until Ioan is suddenly lifted out of his precarious state by a job offer in Milan’s fashion industry. Unprepared for the humiliations he is subjected to, Ioan leaves Milan, but it is too late for his and Michele’s plan to open a pizzeria in Romania together: Michele has taken his life in despair and Ioan returns to Romania alone, accompanied by the ghost of his fondly remembered friend.

Apart from the plot, different political and economic structures have conditioned the films’ production and reception. Carmine Amoroso – already known for controversial topics like transgender – had to confront market censorship during the planning phase of Cover Boy in May 2004 due to the Urbani Law (cf. Fusco Citation2008). Initially, the low-budget film was only presented at film festivals until 2008, when thanks to Istituto Luce, it was shown in a few cinemas. The narrow distribution highlights the film’s difficult position with respect to its ability to penetrate national social discourses, in contrast with Pummarò which benefitted, from the beginning, from a wider national audience because of the director’s popularity as an actor and its high visibility at Cannes Festival in 1990. Placido’s drama had been an initial spark for migration cinema and a national debate about overdue immigration legislation in Italy since the film’s production coincided with the racially motivated killing of the South African tomato picker Jerry Essan Masslo in August 1989. Recognized by the United Nations as a political refugee who had fled his country’s apartheid regime only one year before, he was not granted asylum in Italy as an extracomunitario (cf. Ghirelli Citation1993, 30). High media coverage of the homicide and a mass protest widely supported by Catholic institutions, associations, and unions in the name of the non-citizens in Rome, led to the Martelli Law on 28 February 1990, legalizing the entry and stay of immigrants in Italy, as well as the right of asylum (cf. Camilli Citation2018). The release of Pummarò in September 1990 tragically culminated with a reality mirroring the full spectrum of extreme precarious entanglements affecting just those urgently seeking help foretold by the film.

Photography, migration, and the quest for agency

In mainstream media, photographs of migrating subjects take various functions (cf. Sheehan Citation2018, 1–2). They serve to frame a displaced, traumatized, or victimized subject generally arriving from the Global South that calls for our empathy if not represented in a dehumanizing way. During the challenging moments within the process of migration, photography simultaneously bears a documenting and controlling function if not surveillance per se. Meanwhile, (auto)portrays of migrants, asylum seekers or refugees in mainstream media underscore the desire for self-documentation and self-affirmation beyond a governmental apparatus. Yet, it is in circulation across time, space, and media that photographs of migration take an innovative function and meaning (ibid., 2) such is the case of Pummarò and Cover Boy. The two migration dramas lay bare the perception-conditioning frames of precarity that ultimately question an ethical code of photography (cf. Sheehan Citation2018, 13).

Ambiguous manifestations of class had already been identified as a contributing factor in the social uses of photography in 1965. On the one hand, a missing academic or other qualification for becoming a legitimated photographer had led to a perceived levelling between professionals and amateurs (cf. Boltanski and Chamboredon Citation1990, 152; 159–160). Photography turns into an ‘legitimizable’ (Bourdieu Citation1990, 96), if not ‘illegitimate art’Footnote3 in the consequence of its “social use as a democratic medium of objectivism” (Behnke Citation2008, 135) ceasing Kantian disinterestedness. In-between the users, on the other, this urgently claimed for other ways of distinction marked by their own “class ethos” (Bourdieu Citation1990, 98, emphasis in original) as, e.g., the self-arranged middle-brow family photo (ibid., 28). While displaying the petty bourgeois’ grouping and inscribed family roles (ibid., 19–28), the photo mirrors the traditional class structure and unified nation in a medium of ‘social memory’ (ibid., 30–31). There is also the possibility for transgressing this middle-brow norm in a creative way which according to Bourdieu’s conception relies on the subjects’ status of inclusion into society depending on age, matrimonial status, or professional situation (cf. ibid., 39) not yet intersecting with race. Nevertheless, Bourdieu interprets the quarrel of legitimacy as a consequence of a merely uncontrolled network of agencies whose potentialities are yet to be discovered (cf. Azoulay Citation2012, 22–26). Agency within photography allows to take different position(ing)s as photographer and photographed person, sometimes even simultaneously. Examples of amateur photography in Pummarò and professional digital photography in Cover Boy will uncover different ways to respond or oppose to the zoom of ‘visual exploitation’ (O’Healy Citation2019a, 133).

When representation becomes precarious: Pummarò (Citation1990) and Cover Boy (Citation2006)

Socially restrictive frames that are able (with connotations of criminal justice) to accuse and judge a person of something (Butler Citation2016, 11) are key aspects to both films’ style. Behind these frames are reductive narrative processes that determine the representation of precarity at a material and perceptual level (ibid., 25). Subjects are stereotyped, objectified and, in the most extreme cases, dehumanised (Butler Citation2020, xvi). Since the frames are generally imposed from the outside, the subject is placed in a relation of dependence. This is the basic experience of precarity: to be ‘in someone else’s hands’ (Berlant Citation2011, 192). Nevertheless, representations of precarity structured by iterative frames are fragile, so that ‘a taken-for-granted reality’ can be ‘called into question’ and ‘the orchestrating designs of the authority who sought to control the frame’ exposed (Butler Citation2016, 12). By contrast with Cover Boy (Citation2006), which alternates aesthetically between ‘spectacle’ (Bardan and O’Healy Citation2013, 70) and ‘spectre’ (ibid., 80), thereby addressing the ways in which old and new colonialisms are interwoven, Pummarò largely fails to break with racialising frames, because inequalities are not marked but ‘papered over’ (Forgacs Citation2001, 93), for instance using techniques of mimicry (O’Healy Citation2019, 85). A fundamental problem is posed by the dominant White apparatus (Forgacs Citation2001, 86), which through a primarily external rather than internal focalisation constructs the Black body as an object (ibid., 87) and an ‘erotic spectacle’ (Mulvey Citation1989, 19) for the gaze of a White audience. Through a media-reflexive lens, it will, however, appear in a different light. I will show that photographic acts (cf. Dubois Citation1983, 57) as the historical a priori to film manifest a mode of self-reflection inherent to film, providing a counternarrative to the politics of representation that have previously been identified. As the ‘other’ medium, film cinematographically translates the photographic practices in a certain way. Through a medial process of self-other differentiation, it inquires into the mediatisation of migrants in film. The focus shifts to the historical conditions

in which something appears in film as a medium, opening up the possibility of media reflexivity. … On this view, analysing media [Medienbeobachtung] means inquiring into forms’ conditions of possibility – and thereby outlining the horizon of alternative possibilities for generating meaning. (Kirchmann and Ruchatz Citation2014, 18-19, emphasis in original)

The photographic act as a frame in Italy’s postcolonial cinema

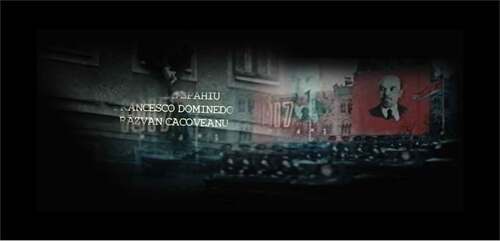

Both films deal with various aspects of Italy’s colonial legacy and critically explore how historical and present-day power relations are interwoven (Ponzanesi and Waller Citation2012, 7; 9). One especially striking phenomenon is the various mechanisms of exclusion, which are still historically rooted in racialising arguments and a colonial logic (Lombardi-Diop and Romeo Citation2016, 370). Techniques of othering are used to make certain features visible or audible, such as Giobbe’s, Kwaku’s and Nanou’s dark skin, Michele’s dark hair or Ioan’s green and yellow ‘Brasil’ T-shirt.Footnote4 They are thus subjected to a ‘segmentation [Rasterung] and division of precarity into relations of inequality’ (Lorey Citation2012, 26). It is not only in late capitalist commodification of precarious bodies as slave or sex workers that signs of a political colonisation are to be found, but also in the context of Romania’s communist government, which opens fire on its own population to maintain its grip on power. Through the internal focalisation on Ioan, whose experience of the capitalist world in the present is repeatedly interrupted by the communist spectre, the two systems are critically juxtaposed and their futures left open (cf. Derrida Citation1994, 45–46).Footnote5 An example can be seen in Cover Boy’s elaborate opening credits, which feature anachronistic visual references to media coverage of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Romanian Revolution and the Tiananmen Square protests. Thanks to the rapidly changing size and shape of the frame and the alternating play of light and shadow on the images and words, the documentary footage straddles the divide between visible and invisible, creating a spectral ‘visor effect’ (ibid., 6) () that anticipates the film’s critique of an economic logic of representation.

Besides historically, economically and politically conditioned legacies, postcolonial cinema is also distinguished by a high degree of aesthetic self-reflexivity, which shifts the focus to the ‘cinematic tools, media technologies, and distribution networks through which we receive images and information’ (Ponzanesi and Waller Citation2012, 7).In this respect, the cinematographic representation of the photographic act in Pummarò and Cover Boy is of particular relevance. Dubois is one of the first to problematize the temporal and contingent dimensions of photography conceptualized as a performative act in which a bundle of factors come into play before and after the shutter is released (Dubois Citation1983, 83–84). From his professional point of view, the photographic act encompasses the operator (photographer), the camera type, the selection and framing of the subject, the scene or setting, the type of photo paper, the communication and distribution channels and the photograph’s intended use, e.g. for advertising or documentation (ibid.). These factors also bring the additional influence of the apparatus to bear, which in a Western central perspective masks differences between multiple perspectival loci (Baudry and Williams Citation1975, 42–44). Dubois’s aesthetic wording though still reveals the photographer’s prioritized position, whereas the staged object to be framed remains passive. The spectator is able to read, analyse and interpret a ‘picture’ which in nearly all cases indexically captures the photographer’s previous ‘setting’ as long as the photographic act did not fail.

From her Visual Studies background, Azoulay reverses the traditional premise of the photographer’s sovereignty, speaking of a network of human and non-human agents determining the event of photography ‘operating in public, in motion’ (Azoulay Citation2012, 18). This brings attention to the general overestimation of the ‘photographed event’ (ibid., 21) in comparison to the often neglected ‘event of photography’ (ibid., 25–27) that never can be said to be completed. Rather, the political potential of photography can only be discovered with the help of the spectator’s transhistorical and translocal ‘civil gaze [that] investigates the context within which the photograph was taken and tries to reconstruct it’ (ibid., 76). This means also to break up long-established one-sided gaze schemata of appropriation that follow a ‘victim-and-perpetrator’-structure such as the isolating ‘frontal view’ (Sontag Citation2003, 70). Instead of bypassing the photographed persons, the ‘citizenry of photography’ (ibid., 77) presupposes the photographed persons’ agency as purposely addressed to the observer:

Spectators predate the moment of photography and are, in fact, taken into consideration in advance by the people photographed – individuals who have come to understand both the form of action in which they participate and the nature of the tool that makes it possible, through actually using photography in their own right. (Azoulay Citation2012, 78)

Reconstructing the event of photography, the spectators are called upon to make use of their own ‘civil imagination [a]s a tool for reading the possible within the concrete’ (ibid., 234) that transgresses the frame of the photographed event. It is enriching to combine the two divergent approaches because they clarify photography’s immanent struggles with agency and sovereignty that ultimately relate to the questions of precarity displayed in both films. In the following, I use Dubois’ descriptive concept of the photographic act but in Azoulay’s broader and contingent sense referring to an uncompleted event of photography and its corresponding implications for analysis.

A frame without justice: Kwaku’s photograph of his brother Giobbe

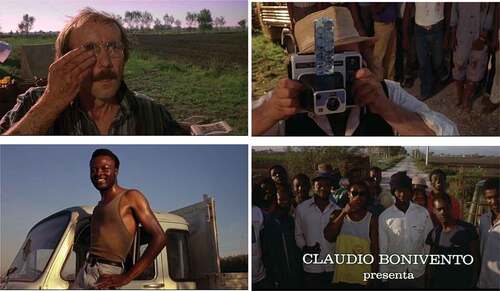

Several photographic acts occur over the course of Pummarò. The first draws particular attention to itself, because it is the only one shown out of chronological order. The establishing shot lingers on a colour photo of Kwaku’s brother Giobbe next to a white truck (), angled diagonally against the backdrop of Kwaku’s brown travel bag. The photo paper is curled slightly inwards, emphasising its ephemeral materiality. The low resolution makes the photo look dark and blurred, which is attributable to the (somberly depicted) situation of Kwaku.

The film’s protagonist is hidden in a dark room on a steam ship on which he has stowed away. He is making the illegal crossing to Italy so he can meet his brother and collect the money he has promised him for his studies. As Kwaku looks at the picture, he listens to an audio cassette on which his brother Giobbe has left him a message. Boastfully, he explains that he has bought a truck with his earnings from working as a tomato picker in Southern Italy. The photo is bordered in the shot by a Ghanaian coin, part of which protrudes over the lower edge and on which the words ‘freedom’ and ‘Ghana’ can be indistinctly made out. The combination of this inscription and Giobbe’s victorious pose in the photo suggest a symbol of freedom – at least for the moment. Correspondingly, the framing of the photo captures its indexical nature only in interfuit as if to question its reality:What I see has been here, in this place which extends between infinity and the subject (operator or spectator); it has been here, and yet immediately separated; it has been absolutely, irrefutably present, and yet already deferred. (Barthes Citation1981, 77)

The ambivalence of visibility and invisibility inscribed in photography prompts us to ask what can and cannot be seen in this photo. Although the protracted shot allows the audience to carefully study every detail of the photo, it does not tell us anything about the event of photography or rather the different conditions of its production in a certain context. It is notable that the word ‘justice’ on the lower edge of the coin is hidden, cut out of the film’s close-up on the photograph. The symbolic figure of freedom is made porous by the uncanny framing (ephemeral materiality, low resolution, darkness, reference to absence) whose figurative meaning for Giobbe’s precarious life only becomes clear retrospectively. It is only in the subsequent flashback that light is shed on the actual, turbulent circumstances behind the photo’s production, which the photo itself is silent about. Giobbe has defied the exploitation and humiliation inflicted by the mafioso landowners by stealing the boss’s gun and truck. He is posing in a moment of rebellious triumph, standing on a step on the side of the truck and ringed by a semicircle of other Black fieldhands. He asks his White colleague and friend, the professore, to capture the ‘historic’ moment on his Polaroid. Astonished, the professore photographs the scene from a low angle, while the other Black fieldhands observe Giobbe’s position of superiority over the angrily staring White mafia boss with amused, sceptical or anxious expressions.

In the intersection of these different gazes (), the photographed event can no longer be understood as a coherent reference to the event of photography and admits of multiple interpretations (Lutz and Collins Citation1991, 135). It can either be read as a sign of self-empowerment, in which history and image archive are redefined from a subversive, Black perspective, or as an attempt to rob the Black subject with his ‘shining surface of black skin’ (Mercer Citation1994, 183–184) of his voice and movement, as ‘a form of second-order objectification’ (Forgacs Citation2001, 88).

This ambiguity is also suggested by the inversion of the photographic act in the film. Showing Kwaku’s perception of Giobbe’s triumphant moment of freedom before going on to retrospectively tell the story behind it changes the audience’s perspective through a media-reflexive juxtaposition of still and moving image. For, while film ‘is protensive, hence in no way melancholic’, a photograph ‘breaks the “constitutive” style (this is its astonishment); it is without future (this is its pathos, its melancholy); in it, no protensity’ (Barthes Citation1981, 90). Accordingly, the extended static shot of the photograph at the start of the film presents the audience only with the illusion of Giobbe’s abiding triumph; by showing the photographic act in moving images, it reveals that Giobbe, who is actually a victim of racist discrimination, is only pretending to have achieved his ‘good-life fantasy’ (Berlant Citation2011, 194). That is why the word ‘justice’ drops out of the cinematographic frame. Giobbe is only spectrally present to his brother and the audience through a medial ‘visor effect’ (Derrida Citation1994, 6). The photo showing him as a Black man triumphing over the White mafia boss is understood right from the outset as a ‘living image’ (Barthes Citation1981, 79), in which Barthes locates the punctum of photography:

He is going to die. I read at the same time: This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. By giving me the absolute past of the pose (aorist), the photograph tells me death in the future. (ibid., 96)

Kwaku and the audience are thrown into a time-out-of-joint, rooted in a multilayered experience of time in which the passage from ‘disadjusted’ to ‘unjust’ (Derrida Citation1994, 20–23) is revealed only by a continuous shift to a later uncertain point in time. By interweaving the media of photography and film, Pummarò seeks to reflect on presence and absence in temporal, phenomenological, epistemological, and justice-related respects. So even if Barthes’ transient conception of photography promises no future, Giobbè’s gaze captured by the photo is still addressing his spectators claiming for more justice. The inquiry into what is visible and what remains invisible reveals the colonial legacies inscribed in photographs in various ways, both in the past and in the spectator’s present.Footnote6

The photographic act as a form of black agency in Pummarò

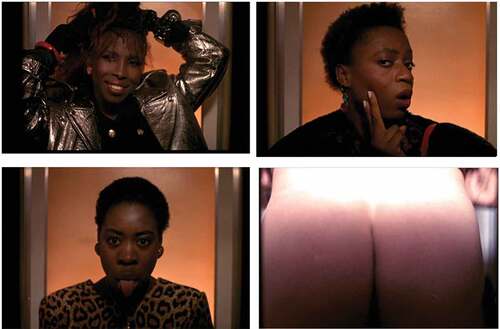

Contrary to what one might expect, it is in marginal spaces on the periphery of Pummarò that Black migrants are able to develop agency through the photographic act. One example occurs on a small piazza in Rome where a White pimp sells the services of his three Black sex workers, hidden behind the curtain of a photo booth, who are cherished by his White male clients for their exoticism. The first thing the audience sees is three flashes of light () as Giobbe’s girlfriend Nanou () and her two flatmates take three photos just for fun. These snapshots are accompanied by ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (1970) by the Jamaican band The Melodians, a song with a Rastafarian background. Rastafarianism, a religious movement of the ‘Black Israelites’, began in Jamaica in the eighteenth century and resists the colonial, ‘Babylonian’ practices of Whites towards local Black populations, for instance by reading the Bible ‘through Black eyes’ (Ebbinghaus Citation2021). This song also covertly expresses a postcolonial critique directly addressed at the former colonial power of Italy, for the ‘King Alpha’ mentioned in the song is the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (1930–1974), who Rastafarians regard as the redeemer whose return will bring salvation.

The photo booth offers a shelter where Nanou and her flatmates can pull a cheeky face at the colonial gaze. Although the three young Black women’s conspicuously styled clothing, make-up and jewellery do not disguise the true reason for their presence, two of the photographs that they take, rather than showing the sex workers as we might expect, instead expose the White buttocks of a middle-aged Italian man (). These snapshots, taken deliberately or accidentally by the three young women, reverse the White male gaze (cf. Ponzanesi Citation2016, 378), which sought in the photo booth to fragment the Black female body en détail and in close-up for its own sexual gratification (cf. Mulvey Citation1989, 20; Fanon Citation2008, 89). The White male body is mockingly reduced to a richly symbolic body part that connotes the satisfaction of needs and drives. This counteracts the reduction of the colonised Black man to his phallus by the White coloniser (Fanon Citation2008, 140).

Embedded in a series of ‘still-moving-images’ (Campt Citation2019, 80) that flash by ‘at the rate of the blink of an eye’ (ibid., 81), this unmasking briefly and without notice turns the course of the narrative up to this point on its head, as if we had had a momentary lapse of vision. Accompanied by ‘Rivers of Babylon’, the interweaving of still and moving image can, like at the start of the film, be understood as an embedded contemporary Black artistic practice that resists by negating. It disrupts the frequency of images (ibid., 81–82) so that the visual flow of the White apparatus and its ideological effects are broken (cf. Baudry and Williams Citation1975, 42). Moreover, motif and snapshot technique significantly deviate from the conventional (self-)arranged petty bourgeois or peasant family photograph. Due to their illegal status in Italy with no residence nor work permit, all non-citizens in Pummarò are formally excluded from a typical working class, bourgeois, or national frame (cf. Bourdieu Citation1990, 39; 44).

Just before the final credits of the film, a similar gesture of Black subversion can be seen in the final photographic act. After Kwaku and Nanou have identified Giobbe’s body in Frankfurt, they walk arm in arm through the city’s Christmas market. In a medium shot, the White apparatus captures their pain-stricken faces, which in the dark December night become almost invisible to the audience. The camera keeps following them in a wide shot that opens up the space into the distance. We witness the final events from a transcendent bird’s-eye perspective. As the credits are about to roll, the film grabs the audience’s attention again when the vivid red of Kwaku’s jacket and the white of Nanou’s, which gleams in the darkness, are mirrored by the colours of a Father Christmas costume worn by a man holding a Polaroid. He points the camera at their faces without asking permission. Kwaku and Nanou lower their heads slightly, turn their backs to him and disappear into the crowd ().

Denied a portrait of these characters’ souls, the audience beholds merely a ‘fantasme d’image’ (Dubois Citation1983, 89) that rearticulates the discrepancy between visibility and invisibility, the photographer’s imaginary gaze at their fleeting subject.

The final photographic act once again marks a hegemonial and (thanks to the reference to Christmas) explicitly moral conflict. Having been repeatedly ‘fixed’ by the White gaze as ‘Negroes’ (Fanon Citation2008, 95) devoid of autonomy, Kwaku and Nanou now deliberately turn their back on the White apparatus, which they are no longer willing to subjugate themselves to. The interdependence between White subject and Black object, historically marked by mutual alienation (ibid., 12), is subverted one last time. The characters’ refusal to be photographed in their moment of suffering directs the audience’s attention to the voyeuristic attitude inherent to the Eurocentric gaze at the ‘Other’. With a last but failed photographic act right at the end, the film casts a critical self-reflection back on its immanent White apparatus. Focused on ‘the pain of others’, it brings to mind the enduring colonialism that determines the conditions in which images of people of colour are produced and received. At the same time, the ‘oppressed’ photograph invites the audience for a ‘civil imagination’ (cf. Azoulay Citation2012, 231–234) by envisioning the event of photography ‘from the other side’ by once walking in Kwaku’s and Nanou’s non-citizen shoes: Which emotions from Kwaku and Nanou could the camera not capture? Where is their gaze now directed to, where are they heading to? What in their mind needs to be changed? What will they wish for their future and where can they find it?

So far, film and Polaroid cameras are mainly in the hands of a professional as Michele Placido or rather privileged White people like the professore. Viewed through a postcolonial lens, however, critique of and resistance to this lopsided state of affairs is still possible through embedded forms of Black agency thanks to amateur photography: the initiation of a self-stylized portrait from a superior position (see ), the rebellious, nonconformist and anti-bourgeois snapshots against the White appropriation of the Black body (see ), and, eventually, the Black refusal to the White gaze (see ).

Photographic acts as representation of a white male gaze in Cover Boy

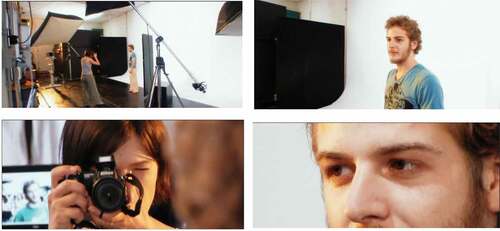

The suggestive title Cover Boy: L’ultima rivoluzione (Citation2006) already anticipates the photographic act: the production and reception of advertising photos. This theme dominates the second half of the film, when the Romanian immigrant Ioan, until that point living in very precarious circumstances in Rome, is discovered by a fashion photographer in the middle of the shopping streets. Initially, the photographer is anonymous and the camera develops an agency on its own (cf. Azoulay Citation2012, 18–19) ().

Ioan does not know that he is been photographed without his consent; a distant spectator of the photograph can only guess so as Ioan is photographed through the rear window of a car and turns the head in the opposite direction of the camera’s eye. Later, it becomes clear that dissimulation is a paradigmatic feature of the event of photography in Cover Boy. Through the round aperture of a digital camera, the audience sees the cross-shaped cursor point at Ioan’s face, digitally measuring the distance to its object as though hunting a wild animal. The clicking sound that follows as the shutter is released marks it as a camera. Only in the next shot the spectator realizes the person operating it: a professional Italian photographer with a camera under her arm, who walks quickly to try and catch up with Ioan. When she reaches him, she grabs his left shoulder from behind without saying a word, bringing him to a stop. After getting his consent, she takes the first pictures right there on the street, capturing Ioan’s face as he looks directly into the camera. When she offers him a new job modelling for a fashion label, he accepts without hesitation.

In this use of technology to ‘capture’ Ioan, and the photographer’s subsequent physical approach to her model, we can already see a gesture of appropriation that is also characteristic of the following professional photo studio shoots. A crucial aspect is the intersection of different gazes that are linked together by the use of shot/reverse shot: ‘the photographer’s gaze’ (Lutz and Collins Citation1991, 134) at Ioan’s body and face and the medially doubled ‘returned or refracted [gaze] by the mirrors or cameras’ (ibid.) behind the photographer, which show the pictures she has just taken of Ioan, intersect with Ioan’s ‘non-Western subject[’s] gaze’ (ibid.), which focuses on the photographer (). In this intersection, which includes the audience’s gaze, the object of the image is constructed as feminised and orientalised (Said Citation1985, 103). As the gaze ‘is by no means coterminous with any individual viewer, or group of viewers’ and ‘issues “from all sides”’ (Silverman Citation1992, 130), the male (‘maker’) and female (‘bearer’) roles in the production of meaning (cf. Mulvey Citation1989, 15–16) can also be reversed and differentiated. When the fashion photographer’s male desire to see meets Ioan’s feminised, receptive gaze, it breaks the heterosexual gender logic and rearranges the material positions between male and female (cf. de Lauretis Citation1987, 2). Ioan’s traumatic loss of his formative political and personal father figures leads him to a crisis of masculinity (Silverman Citation1992, 52–53); an ‘ideological fatigue’ (ibid., 54) and loss of power that symbolically implies a castration (ibid., 4). His humble non-Western gaze is addressed to the photographer who, for a moment, sets down the camera and holds a direct eye contact with Ioan but eventually does not probe for its civil claim.

Compensating for this loss, the photographer instead uses her Nikon Coolpix 5700 (admired at the time for its exceptional zoom performance) to easily gain power over Ioan’s body, which is photographically dissected into and appropriated by fragments (cf. Mulvey Citation1989, 20): from wide to medium shots, to a close-up of his face and finally an Italian shot of his eyes (). Although Ioan is not a person of colour, his framing as exotic and mysterious Caucasian race resembles the alienation of the colonised object in the Eurocentric White gaze (Fanon Citation2008, 95), which Frantz Fanon experienced as a fragmenting of his self:

And the Other fixes me with his gaze, his gestures, and attitude, the same way you fix a preparation with a dye. I lose my temper, demand an explanation … Nothing doing. I explode. Here are the fragments put together by another me. (ibid., 89)

Cast as a Southeaster European in a green and yellow T-shirt emblazoned with the word ‘Brasil’ (), he is ‘screened’ for his qualities as a model of the Global South and his value for possible marketing strategies in the Western world is assessed. This is also evident when the photographer, fetishising his extremely White skin (a typical Far Eastern (beauty) feature), uses photographic lamps to illuminate it. Later, she praises Ioan’s face for being very ‘pulito’, revealing her (albeit unconscious) racist attitude to Ioan, whose naive nature has to be ‘domesticated’ for Western needs (cf. Hall Citation2003, 239–242). These cinematographic ‘technologies of gender’ (de Lauretis Citation1987, 18) accentuate Ioan’s naive, feminine, oriental aspects, which in the gendered visual logic assign Ioan to a lower social position than the photographer.Footnote7 Unaware of this, Ioan grants the photographer his ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ (Mulvey Citation1989, 19): Her inner world remains hidden, while his, in accordance with a ‘code of social inferiority’ (Tagg Citation1988, 37) is fully exposed when he faces the camera and allows himself to be photographed (). We observe another instance of the asymmetric, commodified ‘looker-lookee relationship’ (Lutz and Collins Citation1991, 145), which during the whole event of photography () involves a class dimension due to the nearly always hierarchical perspective that hinders an approximation at eye level.

Before and throughout the fashion show, Ioan finally recognises the framing he has allowed himself to be forced into due to his dire financial straits. From his perspective, we see him critically studying his fellow models one by one. In line with an ‘ethno-marketing’ (Ponzanesi Citation2016, 381) that embraces diversity for calculated, strategic reasons, they have been cast from lightest to darkest skin, which in combination with other presentational devices such as clothing, lighting, props, movement and music promises big business. As Ioan parades before the audience, the flashes of the press photographers’ cameras are timed to coincide with Nancy Sinatra’s refrain: ‘Bang bang, he shot me down. Bang bang, I hit the ground.’ Bardan and O’Healy (Citation2013, 78–79) suggest that while this song plays Ioan is remembering his father, who was shot dead. The synchronisation of the lyrics with the flashing cameras also signals the exotic and erotic framing of the Other in the photo shoot, which robs him of his own identity and moulds him to Eurocentric fantasies. The doubling of Ioan’s ‘returned or refracted’ gaze (Lutz and Collins Citation1991, 134) achieved by combining the video footage of one of the journalists at the fashion show with that of the film camera results in several very blurred images. As a mise-en-abyme, it self-reflexively draws attention to the construct of the exotic Other. Ioan’s actual otherness, meanwhile, like that of all the other models, is negated in the photo shoot.Footnote8 The director Carmine Amoroso probably refers to Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (Citation1966), a film set in the 1960s that tells the story of the young British fashion photographer Thomas. Blowup plays with the relation between ‘photography’ and ‘shooting’ in a number of different ways. For instance, it draws a parallel between Thomas secretly photographing a couple having an affair and the man then being shot dead shortly after. It also brings attention to gendered framings in a fashion world ordered along heterosexual, androcentric lines.

The appropriative function of the photographic acts depicted in Cover Boy resonates at an intermedial level with the contemporary paintings that Ioan looks at in the photographer’s luxury apartment. One of these is a portrait in red and black tones. His eyes travel up the painting in unconventional fashion from bottom to top, fragmenting the image into its individual parts. He realises that it is not an image of Christ on the cross, but an artistic transposition of this motif to the idealised communist freedom fighter Che Guevara (). Both his attention and the audience’s are drawn to two red rings painted around his stigmata and his head. These rings can later be recognised as a leitmotif of the photographic act, framing a Western aesthetics of suffering used to generate media attention for commercial ends. In the photographer’s orientalist gaze at Ioan, this circular selection pattern recurs at the end of the film.

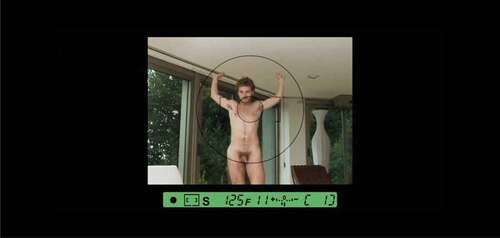

Still in bed after spending the night together, the photographer bends over Ioan, points the camera at him and, completely unannounced, photographs him naked. He is still half-asleep and unable to fend her off in time. Her powerful pose again recalls Antonioni’s Blowup, which was advertised with a film poster showing the young fashion photographer Thomas in the same pose, bent over his female model and forcing her to submit to photographs and other acts. When Ioan expresses unease with what she is doing, stands up and turns away, the photographer is unperturbed. Under the pretext of his contract, she gives him further instructions, ordering to bend his arms over his head in a pose of surrender and to slowly walk towards her. The audience takes the photographer’s perspective one last time: looking through her camera’s circular cursor, she orders Ioan to walk towards her. The cursor moves from Ioan’s head to his chest, and she shoots the photo, striking him right in the heart (). This is not the usual cliché of someone being struck by Cupid’s arrow, but something far more negative; this image of suffering, in which his genitals are visible, is later used to frame Ioan repeatedly without his knowledge as a surrendering male victim (cf. Silverman Citation1992, 3).

A dehistorized frame: Ioan’s commodification as victim of an ideology

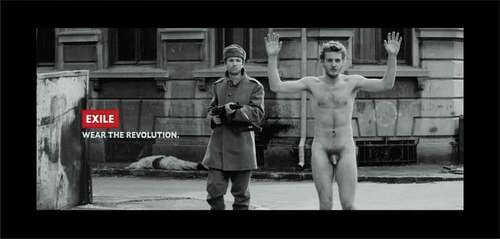

Ioan is unpleasantly surprised when he sees his nude photo at a vernissage for the fashion label ‘Exile’. The photograph, taken in an intimate context, has been overlain in multiple ways by an invisible hand with a famous black and white photograph of the Romanian Revolution () and the brand’s name plus the slogan ‘Wear the revolution’. Contextualised in the revolution against the communist regime, the picture also reflects the idealized black and white vanitas Ioan had recognized in the photographer’s paintings of Che Guevara as Christ (). The original photo shot by Camil Dumitrescu shows a uniformed Romanian soldier standing behind an impoverished middle-aged man, whose hands are raised, and threateningly pointing a Kalashnikov at him. In the background of the photograph two anonymous murdered persons are lying on the sidewalks who in the process of photo design are bypassed as two ‘present absentees’ (Azoulay Citation2012, 47). Beforehand, Ioan had found this and other photos of the ‘Final Revolution’ on the photographer’s desk, which caused him to relive in moving images the traumatic memory of his father being shot. As the two photographs’ differential traces are suppressed (cf. Baudry and Williams Citation1975, 42), it is impossible for the spectator to deduce two instead of one photographed events. The same supplies for the two different events of photography underlying the picture. The digitally processed image does not anymore correspond to a photo that indexically refers to a single event of photography even if its black-white colouring pretends to be documentary. A reference to a disadjusted (‘désajusté’), unjust (‘injuste’) time (cf. Derrida Citation1994, 22) is inscribed into the dissimulated photographic act, which then recurs in media-reflexive form in the two freeze frames from the resulting fashion photograph that are shown immediately afterwards. It echoes the violence Ioan, his family and conations have experienced in Romania by the communist regime but also the injustices he has encountered as a non-citizen in Italy, especially the regular bypassing of his agency and personal background by the photographer.

While in the first frame, notably an American shot, Ioan is frozen in the Romanian war scene for several seconds, emphasising the brutality of the Romanian soldier pointing his Kalashnikov at the back of the naked, surrendering Ioan (), the second, longer shot is a medium close-up of the same fashion photograph lingering on the punctum: Ioan’s petrified face. Unlike in the previous photographic acts, Ioan is no longer looking straight into the camera. His absent ‘out-of-frame look’ (Lutz and Collins Citation1991, 141) towards the bottom right corner of the frame is averted away from any spectators and towards an off-screen space as if to invite the spectator’s civil imagination to investigate what contextually lies beyond the frame. This turn inwards, or to a point outside the scene, implies ‘a view from “elsewhere” … in the margins of hegemonic discourses’ (de Lauretis Citation1987, 25). The morbid or even bizarre, extra-terrestrial framing of the freeze frames is reinforced by a blue light and space-age electronic music. Significantly, one of the photographer’s older colleagues praises the poster as ‘fantastico!’

In the reception of the advertising photo, the intersection of Ioan’s dismayed, non-Western gaze, the likewise horrified Western gazes of three other young reflector figures at the bar next to Ioan and the older man’s appreciative comment invite the audience to reflect critically on a visual construct that has lost all coherence (ibid., 135–136). What for some of the viewers is a cool, superficial image that can be used for fashion marketing is for Ioan a source of emotional distress due to his deep-rooted psychological trauma. The photographer’s underhand photographic practice appears to be reflected in an image of war. A parallel is drawn between the practices of the (communist) war – shooting and killing with a rifle – and those of (capitalist) guerrilla marketing – shooting photos and stealing identities. Like Kwaku and Nanou in Pummarò, but with more control over his destiny, Ioan finally steps out of the Western zoom. On the street outside, Ioan denounces the photographer’s unethical gaze by subjecting her to a repugnance-filled ‘return gaze’ and exclaiming ‘vergognati!’ (shame on you!). She responds only with a lascivious, nonchalant stare. He does not meet her gaze but turns around and walks swiftly away. While heading towards the Danube valley on a car ferry and gazing at the blank horizon, Ioan visualizes his dead friend Michele and the plans he once envisioned with him. By finally leaving his process of migration and his past behind, Ioan returns ‘home’ with an own future destination that again bestows a dignified face upon him (cf. Sheehan Citation2018, 13).

Conclusion

Owing to our socialisation and culturalization, when looking at a photograph we are tempted to say ‘This is … ’ referring to its indexical or documentary nature but in most cases, this turns out to be an illusion as photography is not subsumable under this idea of representation (cf. Azoulay Citation2012, 222–223). As the case studies Pummarò (Citation1990) and Cover Boy (2005) have shown, the temporal and spatial distance between the event of photography and the photographed event have by no means revealed a consistent reality but diverging ones depending on a whole network of agencies embedded in intersecting power structures like racism, classism, and patriarchy. Just the latter ones are less visible than assumed and it is quite impossible to dissect them at first glance, if at all, as they are unconsciously inscribed not only in our perception of world but also in the different ways we use media. Art and cinema, which refer to documentary strategies like photography, increasingly reflect this fluent transition between ‘factual and imaginary registers’ (Demos Citation2013, xvi) since the 1990s. By leaving behind ‘post-Enlightenment paradigms of truth’ (ibid.), they strive for an authentic political use of documentary. Passing from Pummarò (Citation1990) to Cover Boy (Citation2006), this tendency literally becomes obvious without pigeonholing each film into only one category. Subsequently, a pluralistic mode of reception is promoted that goes beyond the visible, back to the investigation of the event of photography, uncovering the ‘excess or lack inscribed in photograph’ (Azoulay Citation2012, 25), while challenging the spectators’ imagination. This way, I was able to identify alongside the dominant White apparatus spaces where precarious subjects could exercise an (albeit limited) agency freeing themselves from ossifying gaze structures.Footnote9 It is only thanks to the reflection about multiple agencies that the precarious framings of Global South subjects can be dismantled to renegotiate every ‘truth’ and ‘ethos’ that is at stake as

[t]he struggle between the different modes of using a photograph is not a struggle over the visible, over the ‘truth’ as if the latter were ever simply given in the photography, but a struggle over the mode of being with others – a struggle motivated by concern for the truth reformulated as concern for the possibilities open to other participants to partake in the game of truth. (Azoulay Citation2012, 224)

Even if the White apparatus is of historical and contemporary significance for Italian (migration) cinema, as Fred Kuworno observes in BlaxploItalian (Citation2016), this apparatus is never able to fully appropriate vulnerable Global South subjects (cf. Azoulay Citation2012., 27) – neither within Eurocentric frames, nor within ones embedded in their own religious or cultural perspectives, as Corazones de mujer (2008, Kiff Kosoof) likewise demonstrates (Mazzara Citation2013, 42). As in Pummarò and Cover Boy, it articulates the possibility of a transgressive form of photographic representation ‘which is able to constitute us [people of colour] as new kinds of subjects, and thereby enable us to discover places from which to speak’ (Hall Citation1994, 402).

However, the fact that the self-representative acts of agency by precarious subjects are relegated to the easily overlooked margins of Pummarò and to the very end of Cover Boy reveals the unequal distribution of possibilities for representing self and others – a ‘symbolic bordering’ (Chouliaraki Citation2017, 19). Similarly, attempts at genuine self-representation by migrants using selfies have been undermined by their remediatisation in European news media, and so this representation migrates into subcultural formats. Still the influence of colonialism is persistent that ‘the epistemologies, stories, and cultures of the Global North crowd out the voices of the Global South.’ (Risam Citation2018, 69). A democratic society that identifies itself with values of dialogue, freedom of expression and political self-determination is incompatible with these divided, hegemonically structured strata of representation and communication. For a society to be democratic in a proper sense, all the (precarious) subjects living in it must be legally afforded the possibility of an independent form of self-representation to secure their agency.

Disclosure statement

I confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stella Lange

Stella Lange has been a postdoctoral researcher within the FWF project Cinema of Migration in Italy since 1990 at the Department of Romance Studies, University of Innsbruck. She is currently a Max Kade Visiting Research Scholar at the Department of Comparative Studies at Harvard University.

Notes

1. Unlike Ghana, a Global South country in the strict sense (see N. N. 2023, World Population Review), Romania and Albania – which both in migration cinema and in reality are situated in a ‘deterritorialized geography of capitalism’s externalities’ (Mahler 2017) – can be understood as part of the Global South on an extended definition that also includes ‘subjugated peoples within the borders of wealthier countries, such that there are economic Souths in the geographic North and Norths in the geographic South’ (ibid.).

2. He is only able to get a three-month visa because the film is set before Romania joined the EU (January 2007).

3. Eine illegitime Kunst (1981) – ‘an illegitimate art’ – is the translated short title in German of Pierre Bourdieu’s original short title Un art moyen (1965) which refers to the classes moyennes, the rising lower middle class; the petty bourgeoisie in new service professions (cf. Behnke 2008, 131).

4. Bardan and O’Healy (2013) and O’Healy (2019a) have shown how the migrantized Southern Italian Michele is used to parodically break these colonial frames. Fully invisible, Michele is placed not in the photographic act but next to his barely functioning, literally and figuratively ‘broken’ TV set. It represents Berlusconi’s commercial, politically slanted television whose presence just comes into being in the moment of Michele’s suicide.

5. ‘At a time when a new world disorder is attempting to install its neo-capitalism and neo-liberalism, no disavowal has managed to rid itself of all of Marx’s ghosts. Hegemony still organizes the repression and thus the confirmation of a haunting. Haunting belongs to the structure of every hegemony’ (Derrida 1994, 45–46).

6. The inscription of (neo)colonial legacies in photographs can also be detected in the black and white pictures of African migrants in the professore’s ‘family album’. Its content and function deviate from the White middle-brow model which archives social memory (Bourdieu 1990, 30) because, instead of reinforcing the continuity and unity of a group in present and past (ibid., 31), it rather commemorates single Black non-citizens for the most part dead. The photograph of a white-skinned woman at the home of Giobbe’s friend Isidoro represents a further deviance. Placed out of focus in the background, this photo (presumably of Isidoro’s late wife) remains a lacuna, signalling the taboo of interethnic relationships concerning their right to frame themselves in a working class or middle-brow family photo.

7. ‘The sex-gender system … is both a sociocultural construct and a semiotic apparatus, a system of representation which assigns meaning (identity, value, prestige, location in kinship, status in the social hierarchy, etc.) to individuals within society. If gender representations are social positions which carry differential meanings, then for someone to be represented and to represent oneself as male or female implies the assumption of the whole of those meaning effects’ (de Lauretis 1987, 5).

8. The collocation ‘to shoot a photo’, used in the professional context of the fashion industry, has been metaphorically translated for the critique of images inscribed into the film: the production of a fixed image is associated with the metaphorical ‘shooting’ or objectification of the subject (cf. Forgacs 2001, 88).

9. Bardan and O’Healy (2013, 81) have bestowed their civil gaze upon Ioan, amongst others, by noting the intermedial, transhistorical and translocal reference to the photograph of the ‘Warsaw Ghetto boy’.

References

- Azoulay, A. 2012. Civil Imagination. A Political Ontology of Photography, New York: Verso[2010].

- Bardan, A., and A. O’Healy. 2013. Transnational Mobility and Precarious Labour in Post-cold War Europe: The Spectral Disruptions of Carmine Amoroso’s Cover Boy (2006). In The Cinemas of Italian Migration: European and Transatlantic Narratives , S. Schrader and D. Winkler. ed., 69–90. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Barthes, R. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, New York: Hill and Wang[1980].

- Baudry, J.L., and A. Williams. 1975. Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus. Film Quarterly 28, no. 2: 39–47. [1970]. 10.2307/1211632.

- Behnke, C. 2008. Fotografie als illegitime Kunst. Pierre Bourdieu und die Fotografie. In Nach Bourdieu. Visualität, Kunst, Politik , B. von Bismarck, T. Kaufmann, and U. Wuggenig. ed., 131–42. Vienna: Turia + Kant.

- Berlant, L. 2011. After the Good Life, an Impasse. Time Out, Human Ressources, and the Precarious Present. In Cruel Optimism, L. Berlant. ed., 191–222. Durham: Duke University Press.

- BlaxploItalian. 100 Years of Blackness in Italian Cinema (2016). Directed by Fred Kuwornu. United States/Italy: Blue Rose Films.

- Blow-Up (1966). Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni. United Kingdom/Italy: Carlo Ponti Production.

- Boltanski, L., and J.-C. Chamboredon. 1990. Professional Men or Men of Quality: Professional Photographers. In Photography. A Middle-brow Art, P. Bourdieu. ed., 150–73. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Cult of Unity and Cultivated Differences. Part 1. In Photography. A Middle-brow Art, P. Bourdieu. ed., 13–98. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Butler, J. 2016. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?, London/New York: Verso.

- Butler, J. 2020. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Justice, London/New York: Verso [2004].

- Camilli, A . 2018. La lunga storia dell’immigrazione in Italia. Internazionale 2018, October 10.https://www.internazionale.it/bloc-notes/annalisa-camilli/2018/10/10/storia-immigrazione-italia (2023-20-02).

- Campt, T . 2019. Black Visuality and the Practice of Refusal. Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory 29, no. 1: 79–87. 10.1080/0740770X.2019.1573625.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2017. Symbolic Bordering: The Self-representation of Migrants and Refugees in Digital News. Popular Communication 15, no. 2: 78–94. 10.1080/15405702.2017.1281415.

- Corazones de mujer [Woman’s Hearts] (2007). Directed by K. Kosoof [Davide Sordella, Pablo Benedetti]. Italy: Movimento Film.

- Cover Boy. L’Ultima Rivoluzione [Cover Boy … Last Revolution] (2006). Directed by Carmine Amoroso. Italy: Cinecittà Luce.

- de Lauretis, T. 1987. Technologies of Gender. Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction, Bloomington/Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Demos, T.J. 2013. The Migrant Image. The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis, Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- Derrida, M. 1994. Specters of Marx. The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, New York/London: Routledge [1993].

- Di Muzio, G. 2012. Historische Entwicklung der Migration. In Länderprofil Italien. Focus Migration. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 23 (online) 2012, October 8. https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/laenderprofile/145669/historische-entwicklung-der-migration (2023-20-02).

- Dubois, P. 1983. L’acte photographique, Paris/Brussels: Editions Labor.

- Ebbinghaus, U. 2021. An den Wassern von Babylon. Interview with the religious scholar Andreas Grünschloß. FAZ online 2021 March 25, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/pop/pop-anthologie/pop-anthologie-113-rivers-of-babylon-von-boney-m-17259563.html. (2021-20-08)

- Fanon, F. 2008. Black Skin. White Masks, New York: Grove Press [1952].

- Forgacs, D. 2001. African Immigration on Film: Pummarò and the Limits of Vicarious Representation. In Media and Migration: Constructions of Mobility and Difference , R. King and N. Wood. ed., 83–94. New York: Routledge.

- Fusco, M.P. 2008. Cover Boy. Sogni e dolori dei nuovi precari. In Repubblica 2008 March 19, https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2008/03/19/cover-boy-sogni-dolori-dei-nuovi-precari.html (2023-09-02).

- Ghirelli, M. 1993. Immigrati brava gente. La società italiana tra razzismo e accoglienza, Milan: Sperling & Kupfer Editori.

- Hall, S. 1994. Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory , P. Williams and L. Chrisman. ed., 392–403. New York/London et al: Harvester Wheatsheaf [1990].

- Hall, S. 2003. The Spectacle of the ‘Other’. In Representation. Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, S. Hall. ed., 223–90. London/Thousand Oaks et al: Sage [1997].

- Kirchmann, K., and J. Ruchatz. 2014. Einleitung. Wie Filme Medien beobachten. Zur kinematographischen Konstruktion von Medialität. In Medienreflexion im Film. Ein Handbuch, K. Kirchmann and J. Ruchatz. ed., 9–42. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Lombardi-Diop, C., and C. Romeo. 2016. Italy’s Postcolonial Question: Views from the Southern Frontier of Europe. Postcolonial Studies 18, no. 4: 367–83. 10.1080/13688790.2015.1191983.

- Lorey, I. 2012. Die Regierung der Prekären, Vienna: Turia + Kant.

- Lutz, C., and J. Collins. 1991. The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes: The Example of National Geographic. Visual Anthropology Review 7, no. 1: 134–49. 10.1525/var.1991.7.1.134.

- Mahler, A.G. 2017. Global South. In: Oxford Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory (online) 2017 October, 25, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0055.xml?rskey=XwMWu3&result=1&q=Global+South#firstMatch (2023-20-02)

- Mazzara, F. 2013. Performing Post-migration Cinema in Italy: ‘Corazones de Mujer’ by K. Kosoof. Modern Italy 18, no. 1: 41–53. 10.1080/13532944.2012.743740.

- Mercer, K. 1994. Welcome to the Jungle. New Positions in Black Cultural Studies, New York/London: Routledge.

- Mulvey, L. 1989. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In Visual and other Pleasures, L. Mulvey. ed., 14–26. Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave [1975].

- N.N., 2023. Global South Countries. World Population Review (online) https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/global-south-countries (2023-20-02).

- O’Healy, A. 2019. African Immigration in the 1990s. In Migrant Anxieties. Italian Cinema in a Transnational Frame, A. O’Healy. ed., 78–107. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- O’Healy, A. 2019a. Migration, Masculinity, and Italy’s New Urban Geographies. In Migrant Anxieties. Italian Cinema in a Transnational Frame, A. O’Healy. ed., 108–35. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Ponzanesi, S. 2016. Edges of Empire: Italy’s Postcolonial Entanglements and the Gender Legacy. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 16, no. 4: 373–86. 10.1177/1532708616638692.

- Ponzanesi, S., and M. Waller. 2012. Introduction. In Postcolonial Cinema Studies, S. Ponzanesi, M. Waller ed., 1–16. London/New York: Routledge.

- Pummarò [Tomato] (1990). Directed by Michele Placido. Italy: Cineuropa 92/Numero Uno Cinematografica S.r.l./RAI Radiotelevisione Italiana.

- Risam, R. 2018. Now You See Them: Self-representation and the Refugee Selfie. Popular Communication 16, no. 1: 58–71. 10.1080/15405702.2017.1413191.

- Said, E. 1985. Orientalism Reconsidered. Cultural Critique 1, no. 1: 89–107. 10.2307/1354282.

- Sheehan, T. 2018. Photography and Migration. Keywords. In Photography and Migration, T. Sheehan. ed., 1–21. London/New York: Routledge.

- Silverman, K. 1992. Male Subjectivity at the Margins, New York/London: Routledge.

- Sontag, S. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others, New York: Picador.

- Tagg, J. 1988. The Burden of Representation, Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press.