ABSTRACT

McKerrell, in ‘Towards Practice Research in Ethnomusicology’, advocates for performance to be used as ‘a central methodology’, as a ‘translation of artistic performance aesthetics’ and as a ‘research outcome sited in original performance’ (Citation2019). The translational role for performance is demonstrated in this article through a practice-led investigation into the dynamic relationship between improvised music and dance. The research is based on the analysis of a live performance on Cuban television of ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ by Orquesta Aragón in the early 1960s, where musical gestures are shown to be embodied in the flute and dance solo ‘duet’ performed by Cuban flautist Richard Egües and dancer Rafael Bacallao, revealing the shared memories of a community bound by common cultural experience. Interdisciplinary in nature, analysis is undertaken by a musician-scholar, a film scholar-practitioner and a professional Cuban dancer-animator in order to unearth details of this embodied repertoire, thus translating and making overt culturally implicit knowledge for those outside of the artistic community of practice, and, in some cases, within it. Through re-performance and re-presentation in the form of a recording and animations, the many meanings embodied in the original performance are examined through analytical text, musical notation, visuals, recordings and animation film.

Introduction

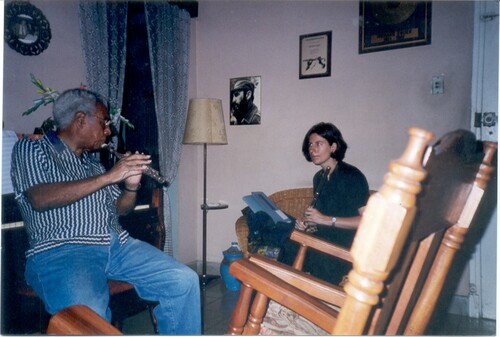

Drawing on Robin Nelson's multi-mode epistemological model for Practice-as-Research (Citation2013: 37), experiential knowledge of Cuban popular music and dance is drawn upon to demonstrate how tacit embodied knowledge can be made more overt through a process of analysis and practical engagement.Footnote1 The music analysis presented here involves detailed transcriptions of flute player Richard Egües’ improvisations by Sue Miller in order to illustrate the musical gestures which accompany the physical gestures of the dancer Rafael Bacallao in the Orquesta Aragón television performance of ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ (shown using video timecode and screenshots). In this way, musical gestures are shown to correspond kinetically to the dance gestures and embodied cultural aspects of the performance. As a past flute student of Richard Egües in Havana, Miller has also had the benefit of first-hand experience of Egües’ approach to Cuban flute improvisation, and this fieldwork informs her analytical approach ().Footnote2

This study has involved practical engagement with the song via the creation of a new recording of the piece ‘Atilana’ by Sue Miller's Cuban music dance band, Charanga del Norte, which, in turn, contains an extended flute improvisation by Miller that is closely related to the original solo by Egües. This recording was created to engage with the musical material and also to provide the soundtrack to a future animation film by Cuban dancer-animator Guillermo Davis based on the research findings presented here; short treatments of these dance moves set to the music on this recording have been created by Davis as part of the initial film project and are available to view online.Footnote3 Through analysis and practical engagement with this eclectic and embodied repertoire, the many social, embodied and cultural meanings in the original televised performance by Orquesta Aragón are made explicit.

Guillermo Davis is a professional dancer with extensive experience in Cuban dance forms and culture, and he is well versed in Afro-Cuban dance and culture, popular Cuban dance styles, ballet and contemporary dance forms. He brings this extensive knowledge of dance and movement to his recent second career as an animator and to this collaborative project. He thus, in Robin Nelson's terms (Citation2013: 37), contributes insider knowledge, experiential, and performative knowledge to the study.Footnote4 Similarly, as a professional performer and Cuban music specialist, Miller brings her academic, experiential and performative knowledge to the musical analysis and has an understanding of the various musical codes which translate to dance movements that are often culturally embodied within this idiom.Footnote5 Miller and Davis have a long artistic relationship and have performed together for many years with Miller's flute improvisations accompanying Davis’ spontaneous choreography, following the model set by Orquesta Aragón's flute player Richard Egües and dancer Rafael Bacallao ().Footnote6

Figure 2. Sue Miller (on flute) and her Charanga del Norte with dancer Guillermo Davis (centre in white) performing at Victoria Park, London supporting Orquesta Aragón, 21 June 2009.

Sarah Bowen, as Davis’ animation mentor, contributes her knowledge of film animation in the final section of this article, adding more theoretical knowledge on visual music and on animating musical movement, suggesting further developments to the work presented here regarding stylised and realistic approaches to animating musical movement. The stylised approach of Davis’ animation work poses interesting questions regarding the value of re-presentation in visual music research.

The televised performance of ‘Atilana’ by Orquesta Aragón

The choreographed flute and dance ‘duet’ performed on Cuban television by Richard Egües and Rafael Bacallao demonstrates the dynamic relationship between musical performance and dance. The Aragón performance on video can be viewed online on YouTube under the title ‘Los Problemas de Atilana – Nostalgia Cubana-Orquesta Aragón’. The outline and analysis that follow will be based on this video.Footnote7 We commence with a description of the original live performance of the song ‘Atilana’ by Orquesta Aragón before specific musical gestures are analysed using musical notation, video timecode, screenshots, photographs and text ().

Figure 3. A video frame of the musico-choreographic duet in the song ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ featuring Richard Egües on five-key wooden flute and dancer Rafael Bacallao.

In the live televised performance of the song ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ by Orquesta Aragón, Cuban five-key flute improviser Richard EgüesFootnote8 performs a flute solo which synchronises with a dance solo performed by the band vocalist and dancer Rafael Bacallao.Footnote9 According to Gaspar Marrero in his book La Orquesta Aragón (Citation2001: 106), televised performances such as this one took place in Havana on a programme called ‘Un Millón de Lunes’ [A Million Mondays].Footnote10 The presence of Tomás Valdés on cello suggests this performance was in 1965 when the band added Valdés to the string section (German Citation2004: 83). Written by Pedro Aranzola Mesa (see Marrero Citation2001: 108), ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ is performed in a light-hearted way by Rafael Bacallao who sings about a Cuban woman called Atilana upset at the appearance of her white hairs; he describes her husband Cirilo's frantic attempts to find hair dye to cover the offending signs of her aging (hair dye was apparently in short supply in Cuba at this time). The piece falls into the category of a guaracha or humorous song and reflects the social mores of its day. The charanga band consists of Pepito Palma on piano and Joseíto Beltrán Guzmán on double bass on the left-hand side of the stage (facing in), Guido Sarría on congas, Francisco Arboláez Valdés (Panchito) on güiro and Orestes Varona on timbalesFootnote11 placed on a raised platform at the back of the set. Singers Pepe Olmo and Rafael (Felo) Bacallao are at the front with the bandleader, Rafael Lay, who is also the first violinist and a coro singer. Next to the three front musicians are Dagoberto González, Celso Valdés (violins) and cellist Alejandro Tomás Valdés who has abandoned his chair and propped up his cello in order to play standing up at the end of this row of strings. Richard Egües is on the wooden five-key charanga flute and situated on the far right of the stage on a raised platform. All the musicians are wearing dark suits with white shirts and pencil-thin black ties. The stage is decorated with flowers which surround the large lettering of the band's name: ARAGON.

Following the verses and their choruses of ‘Ay Atila, Ay Atilana’ Rafael Bacallao moves to the front of the band and the camera moves from Richard Egües (soloing on flute at the side) to Bacallao's dancing which is now centre-stage. The respectably suited Bacallao then performs a variety of movements which map on to the musical ideas played by Egües. The way the band is filmed makes clear that both Rafael Bacallao and Richard Egües are the featured two soloists in the performance of this piece. The split screen used as the solo develops from 2:22 (on the Nostalgia Cubana video) highlights the synchronicity of music and dance gesture. The dance steps would seem here to follow the flute ideas rather than vice-versa, as for example in the mambo steps at 2:56 where Bacallao misses an accent the first time it is played but not on the repeat of the motif (see example 3). Both artists were well known for their creativity in live performance and deviance from any prepared routines would depend on the level of formality. Certainly, this one missed quaver note step is a very small mistake which will not have been obvious to most in the audience within an otherwise seamless performance. Richard Egües, one of the most famous twentieth century improvisers in Cuban popular dance music, was able to develop melodic material sequentially and creatively and therefore his ability to improvise is not in question. Similarly, Bacallao's inventive dance moves were legendary so although specific ideas for this flute solo and dance would have been worked out in rehearsal, these would almost certainly have been varied in less formal performances and in any case improvised at their inception. The nature of the collaboration between Egües and Bacallao has yet to be fully researched however. Bacallao's inventiveness may rest in how he interpreted these melodic-rhythmic ideas played by Egües although it is likely to have been mutual interchange of ideas in rehearsal. Although Egües did not dance on stage (perhaps due to the need to be in the same position for microphone pick-up), his improvisations and compositions were very popular with dancers and were often combined with Bacallao's solo dance performances.

An accomplished vocal improviser and a versatile multi-talented performer, Bacallao's dancing combined many dance styles with both Afro-Cuban and Hispanic-Cuban influence, again often set to Richard Egües’ flute solos. According to musicologist and charanga flute player José Loyola Fernández, Bacallao was the ‘showman’ of charanga but not the first músico bailerín [musician dancer] or cantante-bailerín [singer dancer]; major figures in Cuban popular music such as Dámaso Pérez Prado, Miguelito Valdés, Benny Moré and Orlando Guerra (Cascarita) had set a precedent for this style of musico-choreographic stage performance.Footnote12

The flute and dance performance by Egües and Bacallao forms the basis for the following analysis which looks at these synchronicities in more detail. As to what elements came first – dance movement or musical gesture – that can only be answered by the musicians present at that time in the group and it is likely that their collaborative process would have entailed more of a creative interchange of ideas drawing on a shared culture and a repertory of dance moves and musical gestures developed over time.Footnote13 Certainly, the sequential and motivic nature of the musical tradition draws on stylistic vocabulary and a clave timeline as demonstrated in Miller's book Cuban Flute Style where Egües’ improvisational style is shown to incorporate motivic development, clave feel and sequential virtuosity (Miller Citation2014: 99–129). This easy matching of dance and flute phrasing is possible because of this shared stylistic vocabulary which was developed from the late nineteenth century and through to the present via the orquesta típicas and charangas performing danzón, mambo, chachachá and other Cuban popular dance styles such as the guaracha, son, guajira and bolero.Footnote14

Analysis of the musico-choreographic routine

In the following analytical breakdown of the musical gestures and dance movements in the Orquesta Aragón video, annotated transcriptions and visual descriptors are employed to form the basis of the music/dance research methodology, in order to reveal specific correlations between musical phrasing and dance movement. Research findings are presented as annotated scores, video timecode, video stills and photographs of the dance movements, together with accompanying text. Timecode from the original performance on video is used to highlight exact points of interest in the Orquesta Aragón video recording of ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ so that readers can cross reference this analysis with the filmed performance. The ensuing analysis is a breakdown of the main movements from the flute/dance solo with an examination of Afro-Cuban and Hispanic-Cuban influence alongside a consideration of social and stage dance traditions and other sociocultural influences. Dance movements are individually described alongside the musical gestures that accompany them to demonstrate the symbiotic nature of the auditory and the visual.

The flute solo takes place over the 2–3 clave-organised montuno pattern of the piano and tumbao pattern of the bass combined with the violin guajeos as shown in example 1 below:

Table

Example 1. 2–3 clave-governed melo-rhythmic patterns underpinning the flute solo (clave super-imposed).

These textures outline the guaracha I-V-V-I chord progression and delineate a 2–3 clave timeline (which is not stated only implied through the ties in to the 3-side of the clave through to the second bar). The violin guajeo pattern outlines the timbale cascara pattern which is also drawn upon in Egües’ solo. The flute and step accentuations relate to this clave feel with percussion patterns underlying these melo-rhythmic textures, some of which are shown in example 2:

Table

Example 2. Timbale bell, güiro and chachachá conga marcha pattern in ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’.

The song is in 4/4 with a cut common feel and, due to the fast tempo of crotchet = 188, the güiro plays the machete rhythm shown in example 2 rather than the busier chachachá pattern, as used by Egües in example 6 where the flute imitates the machete sound. These melo-rhythms underpin the Cuban flute style of improvisation and inform the shared vocabulary of musical gesture and dance movement in this routine.

Rafael Bacallao's staged dance performance draws on a set of moves derived from a variety of traditional dance styles, including Afro-Cuban rumba and religious forms, social dances such as son, chachachá and mambo, bailes de salón such as the danzón and staged dance performance practices. As Loyola Fernández has pointed out, choreographed performances in the Cuban charanga tradition evolved in the cabarets and dancehalls; Bacallao, the main innovator in the charanga format, adopted this style of performance initially while performing with Fajardo's charanga in the 1950s. As one of the innovators of this style, he drew inspiration from the work of showman musicians such as Pérez Prado, Benny Moré (a rumba dancer as well as a singer), and from the routines of 1940s star Cascarita. The synthesis of Afro-Cuban cultural elements with vernacular styles is not new to 1950s and ‘60s performance in Cuba therefore and is an eclectic combination of spiritual and secular music and dance, which in this performance reveals syncretised and synchronised ingenuity.

Throughout the dance Bacallao maintains an erect body posture with very little movement of his upper torso simultaneously reflecting the secular Afro-Cuban rumba and the charanga danzón tradition of the semi-closed hold posture.Footnote15 The corresponding musical phrases of Egües’ flute are similarly based on the charanga flute tradition, forged in conversation with a dancing public and drawing on toques and motifs common to Afro-Cuban drumming, and to instrumental soloing (e.g. flute, trumpet, piano, tres and timbales). Perhaps the most obvious correlations in this performance are the sequences using the mambo steps which match the flute accentuations exactly as demonstrated in the following example.

Social dance steps in creative combination

Mambo step synchronicity

Of all the social dance steps drawn upon by Bacallao, the mambo steps are the most utilised when synchronising with the flute rhythms and accentuations. At 2:46 in the video, for example, Bacallao synchronises his mambo steps with Egües’ notes, building from one to two to four extra taps, as demonstrated in musical example 3.

Table

Example 3. Mambo Step Synchronicity with the Flute.

At 02:46 Bacallao performs outward accents to synchronise with the flute using tapped mambo steps which finish with an accent on the front shoulder – he accents firstly with his shoulder and then with his foot (alternating). Mambo steps are then later tapped out with a double accent on the front foot, as the flute motif is developed rhythmically by Egües. He misses the two-step in bar 158 but otherwise executes the double and quadruple accented notes with mambo steps.

Similarly, the timbales cascara drum pattern outlined by the flute break in example 4 is a 2–3 clave-organised pattern played on the side of the drums (itself derived from an Afro-Cuban toque or call to the orisha deities present in Afro-Cuban styles such as the güiro); it is played by the flute and synchronised with Bacallao's mambo tapped steps. This rhythm is also present in the violin 2-bar guajeo pattern as shown in example 1.

Table

Example 4. Afro-Cuban toque/timbales cascara on flute and rhythmically matched by Bacallao’s steps.

La Suiza or ‘The Skipping Rope Dance’ in Chachachá

The mix of son, mambo and chachachá steps in Bacallao's dance routine is not surprising given that these styles formed a large part of the band's repertoire. These dance steps combine in this choreographed dance with gestures designed to accentuate the musical accents of the flute. One example of the mix of son and chachachá steps is a movement Davis terms ‘El Baile de la Suiza’ or ‘Skipping Rope Dance’ where Bacallao combines the cross-step footwork of this chachachá variant with a danzón-styled upper body position. The ‘skipping rope’ dance is often performed in chachachá performances of ‘El Bodeguero’ or danzón-chá versions of ‘Osiris’ or whenever the coro/melody of ‘Mambrú Se Fue A La Guerra’ is played. It entails the cross steps that Bacallao uses here but most often utilises the arms moving as if using a skipping rope (something that Bacallao does not duplicate here).Footnote16 According to Davis this is a variant of a chachachá step, as he states ‘el chachachá es donde se usa ese baile y una de las variaciones del chachachá es precisamente la suiza’. [the chachachá is where this dance is used and one of the variations of the chachachá step is precisely the ‘suiza’] (Davis 2017). Davis has said that this dance was known as ‘la suiza’ [skipping rope] and attributes this skipping dance to Enrique Jorrín, the bandleader of Orquesta América, one of the leading innovators of the chachachá music and dance style in the 1950s. At 02:42 there is a reversal of the paso zapateo where the cross-step is made to the front rather than behind – un escobilleo por detras (a brushing of the floor behind). The musical gestures are synchronised with these steps in that an axis note of c3 (the dominant note in the key of F major) runs throughout as it is ‘bounced on’ in time with the steps from a sixth, seventh or octave above, which could be seen as mirroring the rise and fall of a skipping rope or the raised cross steps of Bacallao as shown in example 5.

Table

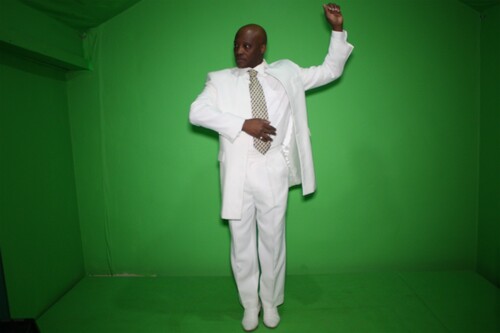

These chachachá cross-steps are accompanied by a closed hold position of the arms common in many early social dances such as the Cuban danzón as demonstrated in .

Figure 4. Guillermo Davis in traditional danzón attire demonstrating the semi-closed hold danzón posture.

European court dances were performed with a stiff upper body and Rafael Bacallao references these bailes de salón styles by often positioning his arms in semi-closed hold position, or with arms behind while performing zapateo tapped steps, drawing simultaneously on rumba and música campesina (rural Hispanic) traditions. The pasos cruzados or ‘cross-leg’ steps involve tapped steps to the side rather than behind in Bacallao's dance.

Afro-Cuban cultural references

Cutting the sugar cane: Makuta and Ogun ()

An example of embodied cultural history can be seen in the hand gesture and spiral movement by Bacallao from 3:12 in the performance video; these movements correspond to the plantation-based cutting of the sugar cane and are represented in sound by a crushed note figure on the flute.Footnote17 This musical gesture corresponds to the sound of the machete going forwards and back, with the longer note corresponding to the second stroke and the crushed note to the short attack representative of a short, sharp-cutting movement.Footnote18 This figure also mirrors the underlying güiro machete pattern as shown in example 2. This cutting gesture is captured musically through the use of a crushed note (acciaccatura) of c#3 cutting into the fuller note of d4, as shown in example 6.

Table

Example 6. Acciaccatura Figure on the Flute: Cutting The Cane.

This cutting movement in sound is mirrored by Bacallao as he starts to turn, bending his knees as he gradually moves round and down in a spiral whilst simulating the cutting of the sugar cane with one hand. Davis describes these turning and twisting movements in Spanish as an ‘espiral caracol simulando el corte de caño con una mano’ [a snail-like spiral simulating the cutting of the cane with one hand]. The sounds and moves of the sugar cane cutting actions reflect the history of slavery and colonialism, a history which continues to haunt the Americas and the Caribbean. Viewed from an alternative perspective, however, these movements could be seen to reference the Makuta dance from the Palo Monte religion (Kongo-derived)Footnote19 and also reference the warrior orisha Ogún from the Santería religion (Yoruba). Through the lens of black cultural theory as put forward by Henry Louis Gates (Citation1989) and Samuel Floyd Junior (Citation1995) in Signifyin(g) theory, these movements could also be seen as manifesting the power of subversion and resistance.Footnote20 The Makuta dance has associations with the machete signifying strength in adversity, protection and spiritual freedom. Footnote21 As Davis explains:

Que es el baile de la Makuta?

El baile de la Makuta es otro baile Kongo y es un baile guerrero. Se baila en parejas sueltas y los movimientos son frenéticos

Que significa el baile de la Makuta

Bueno significa fuerza, el destreza, poder

What is the Makuta Dance?

The Makuta dance is another type of Kongo-derived dance and is a warrior dance. It is danced in open (separate) pairs and the movements are frenetic.

What is the significance of the dance?

Well it signifies force, dexterity and power]

(Davis 2017)

Rumba, Makuta and the Yuka fertility dance ()

At 3:38 Bacallao performs a small jump on the spot, shifting weight from one hip to another, arms outstretched to the front with palms facing down. These movements, according to Davis, reference Kongo-derived dances, including the Makuta warrior dance. The hip movements also mimic the fertility dance ‘El Gallo’ (the rooster), also known as the Yuka dance,Footnote22 via the relaxed hip movement from side to side. As Davis explains:

Hay un saltico en el lugar cambiado el peso de la cadena hace los lados, las manos extendidas al frente, con palma hace al suelo – como el baile de la Makuta, un baile Kongo. El movimiento de cadera puede ser un paso Yuka con cadera relajada con cambios de peso.

[There is a little jump on the spot as he [Bacallao] changes the weight between the hips from one side to the other with the hands extended, palms facing down - like a Makuta dance from the Kongo. The hip movements suggest a Yuka step where the hips are relaxed with changes in weight].

Figure 6. Rafael Bacallao: arms outstretched with palms facing down, showing influence of the Makuta warrior dance and Yuka fertility dance movements.

The oscillations or ‘hoverings’ of the flute (in example 7) create the expectation of a descent and could be seen as reflecting the movements of the feet hovering just above the ground, as in the Makuta dance. Guillermo Davis has made a short animation of the Makuta warrior dance illustrating these arm movements and the hovering footwork to illustrate this.Footnote23

Table

Example 7. Hovering between d4 and b flat3 and d4 and a4 in the flute line creating the expectation of a descent (which follows in example 8).

Afro-Cuban influence – skating and sliding ()

In an interview with Rafael Lam, Bacallao relates that many people assumed he put something on the soles of his shoes to do his skating steps ‘Siempre me preguntan intrigados qué material me echo en los pies para patinar sobre la pista’ [People were always asking me what I put on my feet in order to skate across the stage.] (Interview with Rafael Lam 1988 cited in Marrero Citation2001: 97). It is interesting that Bacallao uses the word ‘patinar’ [skate] here as many of the dance movements in this piece involve sliding or skating steps, together with movements associated with rumba and Kongo-derived dance gestures.Footnote24

Figure 7. Bacallao's signature ‘skating’ step.Footnote32

Table

Example 8. Bacallao’s ‘sweeping the floor’ steps at 3:46 to the musical descent from top d4 to an octave below d3.

This musical descent mimics the sliding movements of the dancer with the descending figures aligning with the shifting of weight between the feet. The final descending phrase played by the flute corresponds with the skating steps, sliding down in a lower line from a3→g3→f3→e3→d3, completing the stylistic octave tessitura of fourth register d4 to third register d3. There is a convergence of an upper and lower descending line: with a stepwise inner line of a3→g3→f3→e3→d3, and an upper descending line of d→-c→b-flat3→ a3→g3→f3→e3→d3 as shown in example 8. These examples reveal physical correspondences (or multi-domain mappings) between the musical contours and rhythmic patterns in the flute lines and the sliding dance movements of Bacallao.

According to Davis, Bacallao's movements draw on the Kongo traditional dances of Palo, Makuta and Yuka where Palo influence is seen in the arms and elbows, and Yuka influence in the hip movements:

el baila Makuta tiene movimientos del Yuka, muchos elementos con la cadera, y tambien se puede encontrar elementos del baile de palo, tal vez en la forma de mover los brazos e codos.

Los brazos al frente, con palmas al suelo?

Al suelo si, porque cuando se hace el gesto del brazo de arriba al bajo termina aqui y lo pone aqui y mueve la cadera. Tiene los movimientos de cadera que se ven en el video … tiene mucho más elementos del Yuka.

He dances the Makuta ..he uses Yuka movements, a lot of hip movement, and also you can find elements of Palo maybe in the way he sometimes moves his arms and elbows.

With arms out front and palms facing down?

Towards the floor, yes because when he makes the gesture with his arm from the top to the bottom, it stays there while he moves his hips. He has the hip movements as seen in the video – he uses the Yuka elements the most.

Generalmente se baila mucha seguidilla en los bailes campesinos – e por ejemplo el zapateo cubano tiene seguidilla e es la misma seguidilla que puede ser parte del improvisación en un baile de rumba – que son dos generos totalmente diferente pero ya puede ver como a la hora de improvisar en un baile se puede transmitir en otro genero bailable.

In general seguidilla [the step] is danced a lot in country dances – and, for example, the Cuban zapateo has seguidilla, the same seguidilla steps that can form part of a rumba dance improvisation – they (rumba and zapateo) are two totally different genres but when the time comes for improvisation, the seguidilla step can be utilized in another dance form.

(Davis 2017)

Embodied history

When conceived as a repository of cultural meanings both past and present, the moving body may be a source to be observed and documented from the outside. Traces of the past may be discovered in the ways in which people execute particular movements and use their bodies. (Buckland Citation2006: 13)

Animating musical movement

Animation scholar and practitioner, Sarah Bowen notes that both dance and animation are visual interpretive forms that are focused on the time-based abstraction and re-presentation of movement. Bowen has underlined the fact that animation and dance both communicate with an audience through movement, syncopation, shape, and rhythm (Brennan and Parker Citation2014); similarly Miller has demonstrated here that there are auditory parallels in music. As a secondary part of the research, mapped dance movements in relation to musical gestures from Egües’ flute solo were applied to a human form representing both the protagonist of the song ‘Cirilo’ [Cyril] and the dancer Rafael Bacallao, enabling the musical dance to be re-presented in cinematic and digital spaces. Initial short animations have been made by Davis and a longer animation film is planned. Shown below is a still of Guillermo Davis’ animation character of Cirilo/Bacallao ().

Figure 8. The human form of ‘Cirilo’ in the animation shorts ‘Los Bailes de Cirilo’ [Cyril's Dances] by Guillermo Davis. (With permission from Guillermo Davis.)

![Figure 8. The human form of ‘Cirilo’ in the animation shorts ‘Los Bailes de Cirilo’ [Cyril's Dances] by Guillermo Davis. (With permission from Guillermo Davis.)](/cms/asset/4387baec-0eef-4d9c-8e54-858412648027/remf_a_1978305_f0008_oc.jpg)

As Bowen observes, the animations created by Davis include his own embodied experience of each step and he distils their forms, particularly the extensions of each step, through the re-presentation of them as key frames, marking the full extensions and contractions of each movement. The animated character of Cirilo simplifies and clarifies the dance sequence where the cut-out animation style makes explicit each movement through its visual stylisation. There is, however, a disconnect between notation of fine dance movements and the limited animation (less than 12 frames per second or fps) that is Davis’ signature style. While realism in animation, (including full animation at 12–24 fps for persistence of vision and conformity to laws of physics in terms of representation of weight and mass), can be seen as more helpful for dance notation purposes, there is interesting potential in ideas around layers of media (style) in the visual re-presentation of fine dance movement that take us away from realism. Davis’ animation is highly stylised which is what is so delightful artistically. Bowen notes that it might nevertheless be clearer if we could break down specific dance movements/phrases using realism (traditional cartoon style animation with its 12 principles; exaggeration, squash and stretch etc.). In terms of purpose and application of animation in this context, movement represented in animation form can exaggerate the fine movements and communicate their key elements more clearly. Embodied dancer-knowledge can inform the re-presentation of fine dance movement through animation. The interesting thing is to see how far these characterisations can go, through the mediations of animation and design, and still maintain and communicate the essence of the dance movement in combination with musical gesture.

People will always want to know what the point of animating the movements is when we only need a vocabulary of movement. Won't live-action recordings be enough one might ask? Which leads us to the benefits of the virtual performer and projections during on-stage performance and the possible different characterisations for different client groups in pedagogic scenarios. Breaking down each movement to 12 / 24(5) fps, for example, can help to clarify movements and aid with the timing of dance movements in educational settings. A follow-on project building on this analysis and the initial animations by Davis is planned to include additional professional animators working in more traditional realism styles for comparison with Davis’ more cut-out stylised representations. We also intend to include dance scholars in a larger scale project to work with Miller, Bowen and Davis on an expanded visual music project. Examples of realism animation styles include Elroy Simmons’ Dance Swine Dance and Ged Haney's Rocket Freudental.Footnote27 Animated dance that is the most realistic is rotoscoped (draw over live-action) as in Jan Fleisher's Citation1933 Walt Disney version of Snow White.Footnote28 Two versions of Cab Calloway performing ‘St James Infirmary Blues’ are combined with visuals from Fleischer studios’ 1933 version of Snow White and indicates a further avenue for exploration building on the practice research presented in this article.Footnote29

Conclusions

This study of one specific performance by a mid-twentieth century Cuban dance band has revealed several cultural particulars within the context of Cuban vernacular music and dance traditions. Making embodied and tacit knowledge explicit using different modes of investigation within an interdisciplinary framework has provided insights into the interconnectedness of music and dance in vernacular performance, demonstrating the usefulness of a translational approach to practice research. The analysis of these music and dance elements and their re-performance and re-presentation through practical engagement has provided new knowledge about eclectic embodied repertoire within Cuban popular culture.

This case study might also provide a methodological template for examining the histories and performance practices of other forms of vernacular dance music, ones which have their own associated improvisations, compositions, performance aesthetics and transnational relationships. This performance-informed approach would certainly favour musical forms with strong oral traditions, and improvisation traditions which build on motivic variation and development.Footnote30

Analytical case studies such as this one can therefore help to shed light on the embodiment of social and cultural history in general and this translational approach may have further benefits in terms of pedagogical application. The production of a new recording and short animations were undertaken in order to engage practically with the analysis of the Orquesta Aragón performance and make tacit embodied knowledge more overt; they are not intended as endpoints in themselves as they have been specifically designed for this research project.Footnote31 Using the knowledge (scholarly and artistic) of the research team, Cuban artistic performance aesthetics have been translated for those mostly outside of the community of practice although these are also articulated for those from within the culture who understand many of these meanings implicitly but are not necessarily able to articulate them verbally. The originality of this project, therefore, lies in the use of interdisciplinary artistic practice to uncover the embodied meanings in musico-choreographic performance. Our practice is part of the methodology; the findings from this project have, to date, been shared within the academic community through conference presentations and in the public domain through talks, live music performances and film showings at Hyde Park Picture House in Leeds and Lawrence Batley Theatre in Huddersfield in 2019, linking to the UK's Research Excellence Framework 2021 guidance on how practice research findings and insights can be effectively shared within and beyond academia. In McKerrell's words ‘the research aspects’ of this project lie ‘in the translational value and communication in text to outsiders beyond the tradition’ (McKerrell Citation2019: 14). We have shown that through practical interdisciplinary research, the embodied meanings in musico-choreographic performance can be demonstrated in detail by combining ethnomusicological scholarship with embodied music and dance experience and practice.

Interviews and translations by Sue Miller

Davis, Guillermo. Leeds, 3 November 2014.

Davis, Guillermo. Leeds, 4 June 2017.

Transcriptions

All annotated transcriptions and musical examples are by Sue Miller.

Figures

Animations and animation frames by Guillermo Davis.

Photographs of dance postures by Guillermo Davis.

Frames taken from the online video performance by Orquesta Aragón are fair use.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the musicians and engineers who recorded the Charanga del Norte version of ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ for this project (musicians Kim Burton, Nick Williams, Ruth Bitelli, Ravin Jayasuriya, Matty Shallcross, Andy Warner, Yuiko Asaba, Jon Lindh, Angela Antwi Agyei, Guillermo Monroy, and sound engineers John Ward and Bill Campbell). Thanks also to Linda Petty for all the animation production support. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions and to the special issue editors Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg and Brett Pyper for their timely editorial work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sue Miller

Sue Miller is a Professor of Music at Leeds Beckett University. She completed her practice-led PhD in 2011 on flute improvisation in Cuban charanga performance at the University of Leeds having previously studied charanga flute improvisation with Richard Egües from Orquesta Aragón in Havana in 2000 and 2001. Her books Cuban Flute Style: Interpretation and Improvisation (Scarecrow Press Citation2014) and Improvising Sabor: Cuban Dance Music in New York (University Press of Mississippi Citation2021) combine the fields of performance, music analysis and ethnographic fieldwork to document and re-evaluate the history of Cuban music performance practice and history in both Cuba and the USA. Her recent British Academy funded practice research project employed experimental archaeology approaches to live studio performance. She is also a professional flute player and musical director of the band Charanga del Norte, which she founded in 1998.

Guillermo Davis

Guillermo Davis is a creative artist based in Leeds. He completed a BA in Animation at the Northern Film School, Leeds Beckett University in 2013 following a long career as a professional dance performer, choreographer and teacher. In Cuba he was a dance teacher from the age of 18, initially teaching amateur and carnival groups. Later he joined the dance company Companía Danza Libre in Guantánamo city, working there for 12 years. In 2000 Davis formed an Afro-Cuban Carnival group and a cabaret dance group in London and later became a dancer with Sue Miller and her Charanga del Norte (2008–2011). He has a wide and deep knowledge of Cuban and Latin American dance and music.

Sarah Louisa Bowen

Dr Sarah Louisa Bowen, filmmaker and moving image theorist, has made several films including Walking Albion in California (Installation/screening, Ferndale, CA, 2017). She has received awards from the University of California for practice-based doctoral research and from BBC Wales for three years of postgraduate study at the National Film & Television School.

Notes

1 See Robin Nelson (Citation2013). Page 37 shows his ‘Modes of Knowing’ model in diagram form.

2 This is documented in Miller's practice research-based PhD and first book. See Sue Miller (Citation2014, Citation2017).

3 These short video animations ‘los Bailes de Cirilo’ set to Charanga del Norte's version of ‘Atilana’ are available to view online via https://www.charangasue.com/2021/08/a-musico-choreographic-analysis-of-a-cuban-dance-routine-animation-demonstrations/

4 Davis is a professional performer but is not a dance scholar and ethno-choreological research is therefore not present in this article although the current authors are looking to include dance scholarship in future interdisciplinary work as we expand into visual music and animation research. Here the focus is on the musical, and the performative aspects, combining ethnomusicological scholarship with embodied music and dance experience and practice.

5 This ‘keying in to the dancer's feet’ is researched further in Sue Miller (Citation2021). See for example the interview with flute player Connie Grossman on page 224.

6 For example, see Davis performing to Miller's flute improvisations in a Charanga del Norte performance at The Civic Theatre, Barnsley on 7 November 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbsd_rZZA3s (accessed 1 September 2020).

7 See Nostalgia Cubana, Orquesta Aragon Atilana. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wobzR-aCm0o. The flute solo and dance starts at 1’43.

8 Richard Egües’ career as flute improviser, pianist, arranger, composer and musical director spanned over seventy years, with 30 years of that time as flute soloist and band arranger/composer with Orquesta Aragón from 1954 to 1984.

9 Rafael Bacallao (born in 1935 in Cienfuegos) started his career as a singer and dancer in José Fajardo's charanga before joining Orquesta Aragón in 1959. More on his career and influences can be found in La Charanga y Sus Maravillas Orquesta Aragón by José Loyola Fernández (Citation2015: 394–401).

10 The programme aired on Televisión Cubana, Canal 6 on Mondays at 8.30p.m. and was produced by Yin Pedraza Ginori. According to Ginori's website blog the programme aired live and only had 13 episodes. See http://elblogdepedrazaginori.blogspot.com/2013/08/television-cubana-como-entre-en-el-icrt.html

11 A type of Cuban drums mounted on a stand derived from the orchestral timpani.

12 See José Loyola Fernández (Citation2015: 395).

13 There are bootleg recordings of the band in less formal situations where different flute solos by Egües are played over the same repertoire and there are other commercial recordings of ‘Atilana’ featuring differently-styled flute solos such as the 1962 RCA Victor recording. Fernando Agüeros, an Orquesta Aragón aficionado living in the Havana suburb of Vibora, has recorded many of Aragón's live and radio performances from this time and has the collection on cassette tapes (see Miller Citation2014: 100).

14 Latin performance aesthetics are outlined in Miller's second book (Citation2021: 12–19).

15 This style of dancing has precedence in the Cuban contradanza/habanera, precursors to the Cuban danzón. In 1789, Moreau de Saint-Méry describes rumba as ‘a certain way of moving the hips, keeping the rest of the body immobile’. Cited in Alejo Carpentier (Citation2001: 102).

16 See Miller (Citation2014: 173–176) for more on the use of la suiza in chachachá.

17 The bass tumbao pattern is said by some to derive from the sound of the cane being cut.

18 Thanks to Dr Lara Pearson for an explanation of multi-domain mapping in relation to this gesture at the British Forum for Ethnomusicology annual conference in 2019.

19 The Kongo region covered Angola, the Congo and Gabon. Afro-Cubans descended from enslaved Africans from this region have specific cultures and religious practices. The dances of Palo, Yuka and Makuta are Kongo-derived.

20 In The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism, Henry Louis Gates puts forward a system of interpretation known as Signifyin’ or Signifyin(g) to examine the double voiced black tradition. Samuel Floyd in his The Power of Black Music applies Gates’ theories directly to music within an African American cultural framework.

21 At the end of a conference presentation of this work at the British Forum for Ethnomusicology conference at Kent University in 2016 one of the delegates, having observed this sugar cane cutting dance by Bacallao, commented that her salsa dance instructor in London referred to this move as the ‘slave step’. In later discussion with Davis, he told me that this move did indeed represent the enforced labour on the Cuban sugar plantations (thereby encoding the slave experience) but that it also represented Makuta – his strength and power. He also mentioned the Yoruba warrior orisha Ogún as also representing force and strength but said that as Makuta is always represented wielding a machete the more direct reference is a Palo Monte one.

22 Robin Moore describes the Yuka drumming as secular and developed out of slave traditions in the mid-nineteenth-century. See Moore (Citation2006: 316). The Yuka dance is performed by folkloric groups in Cuba but is not now a living tradition. Davis has been part of these folkloric staged performances as part of the dance company Companía Danza Libre in Guantánamo city.

23 Guillermo Davis’ animation of this Makuta warrior dance illustrating the arm movements and the hovering footwork is available to view via www.charangasue.com

24 Connections can be made between the African-American vernacular forms such as the backslide of the Electric Boogaloos, the ‘Buzz step’ of Cab Calloway, the gliding steps of Rafael Bacallao in Orquesta Aragón and finally the ‘Moonwalk’ of Michael Jackson but it is beyond the scope of this article to investigate these aesthetic resonances more fully.

25 This sweeping motion is found in the male dancer's steps in Cuban zapateo.

26 Compare for example the columbia rumba dancer's forward glides and shoulder moves from 20:26 in the video with those of Bacallao's performance. The Roots of Rhythm documentary is available on DVD and online https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWqvbY3XBuI

27 These are available online: Dance Swine Dance at https://vimeo.com/52487183 and Der Stuhlkreis by Rocket Freudental’ at https://vimeo.com/472319204 (accessed 5 April 2021). Elroy Simmons Dance Swine Dance is a more traditional realism style and Ged Haney's ‘Rocket Freudental’, while more stylised, is nevertheless also rooted in realism.

28 Jan Fleisher's version of Cab Calloway – ‘St James Infirmary Blue’ (Extended Betty Boop Snow White Version) (starts 00:58) is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bFBx3qYGxL8 (accessed 5 April 2021).

29 Cab Calloway live action https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EcXSbCXxGzw (accessed 5 April 2021).

30 Indeed this methodology could be useful for demonstrating intangible cultural heritage and for providing insights into how orality works (see Ong Citation2012). See also Tola Dabiri's (Citation2020) recent work on UK Caribbean Carnival culture.

31 Miller created a new arrangement of ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’ with her band Charanga del Norte and developed her own solo using the main motifs from the original solo by Egües (for the research project) and created the new recording of the whole song for Guillermo Davis to use for the animation shorts (the research project) and for a later longer animation film for which Davis has artistic goals rather than research ones.

32 Bacallao's gliding steps reference the Makuta dance movements and could also be seen to be similar to the earlier African American ‘Essence’ dance, described by ragtime composer Arthur Marshall as looking like the dancer ‘was being towed around on ice skates … the performer moves forward without appearing to move his feet at all, by manipulating his toes and heels rapidly, so that his body is propelled without changing the position of his legs’ (cited in Stearns and Stearns Citation1994: 50).

References

- Brennan, C., and Parker, L. 1 Aug 2014. ‘Animating Dance and Dancing with Animation: A Retrospective of Forever Falling Nowhere’. In Electronic Visualisation and the Arts: EVA, 63–70. London: BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

- Buckland, Theresa Jill. 2006. ‘Dance, History, and Ethnography: Frameworks, Sources, and Identities of Past and present’. In Dancing from Past to Present: Nation, Culture, Identities, edited by Theresa Buckland, 3–24. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Carpentier, Alejo. 2001. Music in Cuba. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Charanga del Norte. 2015. Atilana—Sue Miller and her Charanga del Norte. CDN00CD11.

- Dabiri, Tola. 2020. ‘Decoding Twenty-First Century Carnival: Orality and British Caribbean Carnival’. Ph.D. diss., Leeds Beckett University, Leeds.

- Davis, Guillermo. 2019. Los Bailes de Cirilo and Makuta. https://www.charangasue.com/2021/08/a-musico-choreographic-analysis-of-a-cuban-dance-routine-animation-demonstrations/.

- El Blog de Pedraza Ginori (known as Yin, ex TV Cubana producer). http://elblogdepedrazaginori.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/television-cubana-como-entre-en-el-icrt.html (accessed 4 March 2017).

- Fernández, Loyola J. 2015. La Charanga y sus Maravillas Orquesta Aragón. Havana: Ediciones Museo de la Música.

- Fleisher, Jan. 1933. Snow White.

- Fleisher, Jan. Cab Calloway Performing ‘St James Infirmary Blues’ to Fleisher’s 1933. Snow White Animations.

- Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. 1995. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 1989. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- German, Héctor Agustín Ulloque. 2004. Orquesta Aragón. Havana: Editorial Unión de Periodistas de Cuba.

- Haney, Ged. 2020. ‘Der Stuhlkreis by Rocket Freudental’.

- Marrero, Gaspar. 2001. La Orquesta Aragón. First Edition. Havana: Editorial José Martí.

- McKerrell, Simon. 2019. ‘Towards Practice Research in Ethnomusicology’. Pre-publication draft research article, published 10 August 2019. https://simonmckerrell.com/2019/08/10/towards-artistic-research-in-ethnomusicology-draft-for-comment/ (Accessed 4 September 2020).

- Miller, Sue. 2010. ‘Flute Improvisation in Cuban Charanga Performance: With a Specific Focus on the Work of Richard Egües and Orquesta Aragón’. Ph.D. thesis and recordings portfolio, University of Leeds.

- Miller, Sue. 2014. Cuban Flute Style: Interpretation and Improvisation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

- Miller, Sue. 2021. Improvising Sabor: Cuban Dance Music in New York. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Moore, Robin D. 2006. Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Nelson, Robin. 2013. Practice as Research in the Arts – Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ong, Walter. 2012. Orality and Literacy. 30th Anniversary Edition. Oxford: Routledge.

- Orquesta Aragón. ‘Los Problemas de Atilana’. ‘Nostalgia Cubana-Orquesta Aragón Atilana’. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wobzR-aCm0o (accessed 15 July 2021).

- Orquesta Aragón 1962. Los Problemas de Atilana – Cójale el Gusto a Cuba con la Orquesta Aragón. RCA Victor label LPD 567.

- Orquesta Aragón 1965. Los Problemas de Atilana—’Un Millón de Lunes’ (‘A Million Mondays’).

- Orquesta Aragón 2004. Los Problemas de Atilana—Orquesta Aragón. LP MUSART EDC- 60393, 3 disc album made in Mexico (German 192).

- Orquesta Aragón 1997. Los Problemas de Atilana—El Mambo Me Priva! Cuban Gold 3 the 60s: 20 Hits Direct From Havana: QBADISC QB-9024. Reissue compilation CD.

- Pugh, Margaret. 2015. America Dancing – from the Cake-Walk to the Moon-Walk. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Routes of Rhythm with Harry Belafonte, Volumes 1–3. 1989 and 1991. Dir. Eugene Roscow and Howard Dratch (Cultural Research and Communication, Docurama DVD NVG – 9476).

- Simmons, Elroy. 2011. Dance Swine Dance.

- Stearns, Marshall, and Jean Stearns. 1994. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Macmillan. Reprint, Da Capo Press.