ABSTRACT

Introduction: The most commonly used treatment for advanced colorectal adenomas is endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). The increased number of EMRs since the introduction of the screening program for colorectal cancer has resulted in an increase in EMR-related complications. This review summarizes the current knowledge for the use of clips for the treatment and prevention of complications after EMR.

Areas covered: The historical development of clips is summarized and their properties are evaluated. An overview is presented of the evidence for therapeutic and prophylactic clipping for bleeding or perforation after EMR in the colon. Several clipping techniques are discussed in relation to the efficacy of wound closure. Furthermore, new techniques that will likely influence the use of clips in the future endoscopic practice, such as endoscopic full-thickness resection (eFTR) are also highlighted.

Expert commentary: Most research focuses on prophylactic clipping for delayed bleeding after EMR of large adenomas. We advocate a distance of 0.5–1.0 cm between aligning clips. This focus may likely shift from bleeding to perforation. Here, endoscopic treatment with through-the-scope clips and large-diameter clips may well replace surgery. The future role of clips will also depend on the further development of new endoscopic technologies, such as eFTR.

1. Introduction

Since the introduction of screening programs for colorectal cancer (CRC), the number of premalignant lesions diagnosed and removed during colonoscopy has increased [Citation1]. Most flat or sessile advanced adenomas can be removed endoscopically using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). Historically, several developments have led to EMR becoming the standard of care treatment of large pre-cancerous lesions in the colon, such as high-resolution imaging techniques, electrocoagulation, polyp snares, submucosal lifting techniques, and endoscopic clipping devices (ECDs).

In 1975 the first ECD, the staunch clip, was introduced in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy in Japan [Citation2]. After the development of an easy clip application system in the late 80s, ECDs were increasingly used to stop serious bleeding, treat intraprocedural perforation, anchor metal stents, and close fistula´s. Between 2002 and 2005, manufacturers introduced new clips with additional attributes, such as a pre-loaded ready to go mechanism, the ability to reposition the clip, rotatability and a larger opening spread of the prongs. Nowadays, ECDs can also be placed prophylactically to prevent delayed perforation or bleeding, especially after resection of a large polyp.

In 2008, the first large-diameter clip was introduced [Citation3]. This is a different type of ECD that is able to grab tissue from all angles, surrounding the lesion. So far, it has not been commonly used for prophylaxis of bleeding.

This review will focus on the use of ECDs and large-diameter clips for the treatment and prevention of bleeding and perforation during and after EMR of flat and sessile lesions with a diameter >20 mm. We summarize various clipping techniques that are used to close large EMR wound beds and perforations. Furthermore, we shortly discuss future perspectives of clipping.

2. ECD designs and manufacturers

The first modern ECD was the QuickClip (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). After introducing a reloadable clip system, it was presented as the first pre-loaded clip in 2002 [Citation4]. In the following years, multiple new clips were marketed with different mechanical properties. Since the three-pronged TriClip has been removed from the market, only two-pronged through-the-scope (TTS) clips have become available. Currently, there are three preloaded clip systems that are most often reported in the literature: the Resolution clip (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), the QuickClip, and the Instinct clip (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA). Since the introduction of the Resolution 360 (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), all available clips are rotatable and pre-loaded. Although these three clip designs are most frequently studied, there are now more clip designs available. An example is the EZ-clip (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), a reloadable clip system to reduce costs. In addition, several clip designs from Chinese manufacturers have recently been introduced for substantially lower prices than the known clips from Japan and the US, but these Chinese clips lack scientific reports regarding their efficacy.

Experience has taught us that most available clips are comparable in terms of safety and effectiveness for treatment and prevention of bleeding. The choice of clips depends mainly on mechanical properties, pricing, availability, and preference of the endoscopist. A recent study presented an overview of the in vitro mechanical characteristics of five commercially available ECDs in the US [Citation5]. In summary, the Resolution clip was reported to have a strong adherence to tissue, generally achieving a minimum adherence of 4 weeks. Some small studies have shown that the QuickClip stays in place between one and two weeks [Citation6,Citation7]. Considering that the majority of delayed bleeding cases occur within 48 h after EMR [Citation8], both these adherence rates should be sufficient to prevent bleeding. However, when the clip needs to stay attached to the mucosa for a longer time, for example, for marking purposes, then a preference may be given to the Resolution clip [Citation6,Citation9,Citation10]. Nonetheless, long-term retention rates of the Resolution clip and the Instinct clip at the first surveillance colonoscopy at 6 months after EMR have been reported to be low for both clips (4.2% after a mean follow up of 7 months vs. 8.6% after a mean follow up of 6 months, respectively), although this difference was found to be statistically significant [Citation11]. The retained clips did not in any case reduce the ability of scar inspection or treatment of residual adenomatous tissue. An overview of a selection of relevant clip characteristics for a number of available clips is shown in Supp. file 1.

3. Clipping for perforation after EMR

Perforation after colonic EMR of lesions >2 cm is reported to occur in only 1.5%, but is potentially a severe complication that may lead to peritonitis, sepsis, and even death [Citation12,Citation13]. Roughly three approaches are available for the treatment of gastrointestinal perforation: conservative (e.g. nil per mouth and wait-and-see), or endoscopic or surgical repair. Colonic perforations can less frequently be handled conservatively than upper gastrointestinal perforations, as bowel content cannot be diverted here as easily. Guidelines therefore advise prompt endoscopic or surgical closure [Citation12,Citation14]. The Sydney tool for deep mural injury has been developed to assist the endoscopist in the diagnosis of perforation depth during the procedure [Citation15]. Full-thickness perforation can be recognized by the ‘target sign’ (particularly type 4–5). Most endoscopists however already choose to place one or more clips over a mucosal defect in case of type 2 deep mural injury (focal loss of the submucosal plane raising concern for mucosal plane injury or rendering the mucosal plane defect uninterpretable) and higher. Endoscopic treatment options include TTS clips and large-diameter clips.

3.1. TTS clip

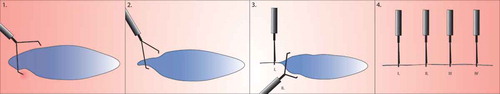

Small perforations <1 cm or near-perforations (type 2–3) can reasonably be treated with TTS clips in a zipper fashion (). In these cases, zipper clipping with TTS clips may be more cost effective than other closure modalities [Citation16].

Figure 1. Zipper closure. Small or oval elongated lesions are clipped in a zipper fashion (30), starting in one corner and working clip by clip to the other corner. With every clip that is placed, the edges close to the clip are pulled a bit closer to each other, so the subsequent clips will easier reach the opposite wound margins.

Larger lesions can often not easily be closed by TTS clips, as the clips have an average opening span between 11 and 15 mm and only have enough reach and strength to approximate the mucosal layers of the four-layered intestinal wall. For larger perforations up to 3 cm, an alternative solution for clipping can be found in a large-diameter clip system [Citation14].

3.2. Large-diameter clip

A large-diameter clip is a large-sized clip that can be used for the endoscopic treatment of large deep or perforating GI wall defects that would otherwise need surgery. Currently, the most commonly used large-diameter clip is the Over-The-Scope Clip (‘OTSC’, Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tübingen, Germany). This Ovesco clip is a circular bear trap imitating construction that is mounted onto a cap on the tip of the endoscope and is available with spiked or rounded clip teeth. Another large-diameter clip system, the Padlock Clip (Aponos Medical, Kingston, NH, USA), is currently under evaluation. Compared to the more concave Ovesco clip, the Padlock clip has a flat design aiming to improve snare resection after placing the clip. The first clinical data proving feasibility and safety of the Padlock clip have recently been published, but clinical data on its efficacy are scarce and large comparative studies are lacking [Citation17–Citation19].

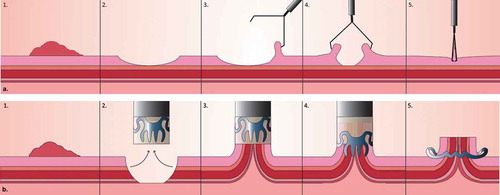

The Ovesco clip has been shown to be safe and effective for the closure of gastrointestinal perforations [Citation18]. It has the theoretical advantage over regular clips that it does not only clip the mucosa together but also closes the perforation in full-thickness (). Data from randomized controlled trials or prospective series confirming the superiority of the Ovesco clip over ECD is however lacking. A meta-analysis from 2015 showed a success rate of perforation closure with regular endoclips of 90.2% compared to 87.8% with the Ovesco clip [Citation20]. A careful interpretation of these closing rates is warranted, because selection bias (i.e. bigger perforations in the Ovesco group) was likely to be present [Citation21]. The ESGE guideline recommends the use of TTS clips for small holes and OTSCs for larger ones. In case an OTSC is not sufficient to close a large perforation, immediate surgical intervention is warranted [Citation14].

Figure 2. Mechanism of action of TTS clip and Ovesco clip. (a). Endoscopic clipping of the mucosal layer with regular clips. (b). 3. The target tissue is sucked in the cap. The Twingrasper or Anchor devices (Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tübingen, Germany) can be used to grab the target tissue and pull the margins into the cap, especially in case of tissue induration. 4–5. When the Ovesco clip is deployed, the clip teeth may slightly push the tissue out of the cap. If the margins of the lesion are not completely inside the cap, this may result in incomplete closure.

Practical drawbacks and complications should be considered before applying the Ovesco clip. The Ovesco clip is placed with a cap placed onto the tip of the scope, which makes re-insertion of the endoscope necessary. This is especially inconvenient in situations where reaching the lesion and/or maintaining a stabile working position is difficult, e.g. in a patient with perforation. Furthermore, clip retention and treatment outcome may be negatively influenced when less tissue is included, but also when the lesion borders are further apart or when grabbing the tissue is impaired because of tissue induration or fibrosis [Citation18]. A technical limitation is that the clip, once deployed, cannot be easily removed. The strength of the clip claws is 8–9 Newton [Citation3].

Although no formal studies of retention of large-diameter clips have been performed, long retention times of several months have been seen for the Ovesco clip in clinical practice [Citation18,Citation22]. But even though the clip is designed as a durable implanted device, removal may be necessary in case of incomplete resection, misplacement, or signs of potential complications. Possible complications include wrong clip placement and clip insufficiency (i.e. the clip cannot hold the targeted tissue together or falls off leading to a perforation), difficult treatment of the remaining perforation after a misplaced clip, luminal stenosis, clipping not only the tissue but also the tissue grasper, and clipping structures adjacent to the gastrointestinal lumen, such as one of the ureters or large vessels [Citation23]. Damage to the abdominal wall has been reported as an adverse event during introduction of the cap-mounted OTSC. However, visual monitoring of the introduction of the cap and taking the individual anatomy of the patient into account when choosing from the available OTSC types and sizes can prevent these injuries [Citation23]. Local ulceration and abdominal pain have also been reported as reasons for OTSC removal [Citation24]. A special cutting device has been developed for the fragmentation and removal of the Ovesco clip, the remOVE DC Cutter (Ovesco, Tübingen, Germany). Successful removal is accomplished in 85–92.9%, but complications such as bleeding and mucosal tearing occur in 4.1–9.5% [Citation24,Citation25]. Overgrowth of tissue over the clip teeth may make fragmentation impossible.

4. Clipping for bleeding in EMR

4.1. Immediate bleeding

Acute intraprocedural bleeding is defined as a non-self-limiting bleeding with a duration of at least 60 s and occurs in approximately 10% of patients [Citation13,Citation26]. The risk is known to be increased in large polyps (>10 mm, with an increasing risk with increasing size of the lesion), proximal location in the colon, flat or sessile morphology, older patients (>65 years old), use of anticoagulant medication and endoscopist experience [Citation26–Citation28]. Other reported risk factors are a tubulovillous or villous histology [Citation26], male sex and type of current used for resection [Citation26,Citation28]. Pure-cut current may promote acute bleeding, while coagulation current may predispose to delayed bleeding. Importantly, these risk factors have not been confirmed in all studies.

Since acute intraprocedural bleeding occurs regularly and endoscopic management with soft tip snare coagulation is often successful, this is generally not seen as a complication, but as a side effect of EMR [Citation29]. However, in <10% of thermal therapies fail to achieve hemostasis and other hemostatic techniques such as clipping are warranted.

4.1.1. TTS clip

Clipping after EMR in the upper GI tract has been shown to be as effective as thermal therapy for the treatment of acute bleeding. Nevertheless, clipping is deemed safer because of the lower risk of perforation [Citation30,Citation31]. These results have been translated to EMR in the lower GI tract. Although the efficacy of clipping for DB in this location is mainly based on case series [Citation32,Citation33], clinical practice worldwide has demonstrated the successful use of clips for bleeding in de colon.

Roughly two approaches can be applied to achieve hemostasis with TTS clips: clipping the bleeding vessel or closing the entire wound area. Clipping the specific bleeding vessel is usually opted as it is faster and generally requires less clips. The disadvantage of placing a clip in the resection ulcer when targeting a bleeding vessel is that it may cause a perforation or a new bleeding at the attachment site of the clip in the ulcer [Citation34]. Due to induration around the placed clip, a delayed bleeding in the same resection area is often challenging to treat as scarring granulation tissue is notoriously difficult to clip.

Clipping the entire wound can be done with the zipper method () or with an adapted method of the zipper closure technique, in case of large or round surface areas ().

Figure 3. Approximating the peripheral wound edges prior to Zipper closure. Larger or round lesions, where the edges are further apart, can benefit from placing a clip in two opposite peripheries of the wound surface, making it more almond-shaped. After doing this, clipping can be continued between the clips in a zipper fashion.

4.1.2. Large-diameter clip

Various studies have reported on the use of the Ovesco clip for the treatment of colonic hemorrhage caused by a variety of underlying problems, varying from a diverticulum, to an EMR or polypectomy scar [Citation35,Citation36]. Hemostasis was almost always achieved, but there is a risk of overtreatment and adverse events. One randomized trial compared Ovesco clips with TTS clips for hemostasis in recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding. Treatment with OTS clips was considered superior to standard treatment with TTS clips for initial hemostasis, but there was no significant difference in recurrent bleeding within 7 days [Citation23,Citation37]. Comparative trials between different clip systems in the colon are not available. Nevertheless, one Ovesco clip is usually sufficient to close the wound, whereas often multiple TTS clips would be needed. Considering the costs in the Dutch health-care situation, one Ovesco clip costs around €300 and is, therefore, more expensive than one or more TTS clips (€60–90 per clip).

4.2. Delayed bleeding prophylaxis

Delayed bleeding (DB) is the most prevalent complication after EMR and may occur up to a month after EMR, but 90% will occur within 48 h [Citation8]. Delayed bleeding can be defined in terms of hemoglobin drop of 2 g/dL or more, bright red rectal blood loss, etc. A more general definition, which is often used in clinical studies, states that delayed bleeding is any anal blood loss occurring after the completion of the procedure necessitating emergency room consultation, blood transfusion, prolongation of hospital stay, re-hospitalization, or re-intervention (either repeat endoscopy, angiography, or surgery) [Citation12,Citation26,Citation38–Citation40]. The incidence of delayed bleeding for large colonic lesions >2 cm is approximately 12% in the cecum, 10% in the proximal ascending colon, 7% at the hepatic flexure, and 2–3% in the left colon [Citation8]. Identified risk factors of DB after EMR include anticoagulant drug use within 7 days after the procedure (OR 6.3; P= 0.005), piecemeal resection, increasing polyp size, proximal location in the colon and intraprocedural bleeding [Citation26,Citation27]. Other reported risk factors are endoscopist experience, liver cirrhosis, obesity, and male gender [Citation39,Citation41–Citation43].

4.2.1. TTS clip

Multiple studies have suggested that prophylactic clipping may be effective to prevent delayed bleeding after EMR of large (>20 mm) flat and sessile polyps in the proximal colon, as these are associated with a high risk of bleeding [Citation44–Citation46] (see ). The hypothesis of prophylactic clipping for delayed bleeding prevention is currently being studied in several studies (see ).

Table 1. Overview of studies on prophylactic clipping.

Table 2. Clinical trials on prophylactic clipping after EMR.

Complete closure for prophylactic clipping is defined as the approximation and compression of resection margins using one or more clips to prevent delayed bleeding. In addition, clipping may treat oozing bleeding. The degree of approximation of the resection margins is generally not specified. Although most studies report a distance of several millimeters between the clips, up to 1-cm spacing between clips has been reported to be effective in achieving complete closure [Citation38]. This practice may greatly decrease the costs of clipping. In the same study, complete clipping resulted in a significant decrease in delayed bleeds from 9.7% to 1.8%, leaving the control group 6 times more likely to develop delayed bleeding (95% CI 2.0–18.5; P = 0.002) [Citation38]. The authors did not observe a difference in effectiveness between complete and partial closure of the resection wound (5.8% vs. 9.7%; p = 0.17).

Nevertheless, complete closure should be attempted, as the risk for delayed bleeding after EMR seems unaffected when only prominent visible vessels in the resection area are clipped (1.4% vs. 5.9%, respectively; p = 0.041) [Citation50]. Standard techniques may not always suffice to close large lesions (>2 cm). For large round resection surfaces, various additional techniques such as clips combined with an endoloop have been reported [Citation51–Citation55]. These techniques should only be used in complex clipping cases by expert endoscopists.

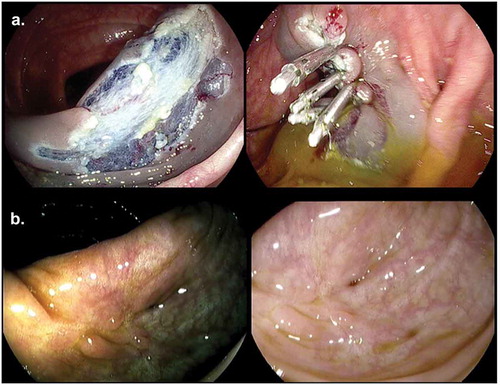

The drawback of complete closure for prophylactic clipping is an aberrant appearance of the EMR scar due to tissue traction by the clips, the clip artifact. It has been reported in approximately a third of clipped patients, especially after prophylactic clipping [Citation56]. It is characterized by mucosal nodules and granular tissue with notches (see ). Distinguishing a clip artifact from a polyp residue or recurrence can be challenging. Where possible, retained clips should be removed in order to optimize endoscopic visibility. A biopsy should be taken in case of uncertainty of the diagnosis.

Figure 4. (a). Prophylactic clip closure of resection field after piecemeal EMR. (b). Clip artifact in scar after EMR with HDWLE and Iscan.

Parallel to the question of effectiveness of prophylactic clipping is the question of cost-effectiveness. Based on the average number of placed clips and estimated average clip cost prices, a rough estimation of the cost-effectiveness of clipping can be made. Bahin et al. calculated with an economic model for prophylactic clipping that an average cost price of €15,57 per clip is necessary to offset the costs of delayed bleeding therapies (average costs per bleed of €2445) when it is applied selectively to proximal lesions [Citation39]. However, this price could be higher when fewer clips are needed to achieve effective prophylaxis.

5. Future concepts

Looking at the future, a different focus for research seems upcoming, responding both to the issue of prophylactic clipping as to new developments in polyp removal and cancer prevention. Future concepts can roughly be captured in three words: improvement, expansion, and competition.

5.1. Improvement

Multiple clips are often needed to close a defect and/or establish endoscopic hemostasis. Application systems for placing multiple clips are currently being developed to save time. The advantage of these systems is that subsequent clips no longer need to be separately advanced through the working channel of the scope. An example is the ClipMaster3 system (Medwork, Höchstadt, Germany), a prototype multiple clip application system that is able to place three clips in a single pass. In a pilot study, no relevant complications were reported and a substantial reduction in treatment time was achieved [Citation57].

Not only clip material, but also clipping techniques will develop in the future. Advanced clip closure techniques to allow adequate closure of large lesions will likely become standard practice, competing with the expensive treatment with large-diameter clips. Case reports and series have reported several of these techniques, using clips in combination with snares and nylon lines [Citation51–Citation53,Citation55,Citation58].

5.2. Expanded use of clips

New techniques and methods to treat large premalignant adenomas and early carcinomas are advancing. Although not yet widely implemented in Europe to date, several advanced endoscopists in expert centers are now performing novel endoscopic procedures such as FTR and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

5.2.1. Clipping in FTR

Full thickness resection (FTR) is a procedure for the endoscopic removal of invasive adenomas with all layers of the abdominal wall becoming included in the excision specimen. First, the adenoma is pulled into the cap and a large-diameter full-thickness clip, currently the OTSC, is placed. Then, full-thickness snare resection is performed of the tissue containing the adenoma. Perforation is prevented by the clip. FTR can also be done with the recently developed FTR Device (FTRD), which combines these two steps [Citation59]. Further development and application of this technique is expected.

5.2.2. Clipping after ESD

In case of suspicion of neoplastic growth into the submucosa, adenoma removal should preferably be performed with ESD [Citation60]. Compared to EMR, ESD achieves a higher rate of en bloc resection and curative resection (46.2% and 42.3% vs 91.7% and 80.3%, respectively). Additionally, recurrence rates are much lower (12.2% vs 0.9%) [Citation61]. These results were achieved in hospitals with experienced endoscopists and state-of-the-art equipment and devices. However, the incidence of delayed bleeding complications are similar to those in EMR and perforation risk is even increased compared to EMR (4–10%) [Citation13,Citation61,Citation62]. This incidence may increase in less experienced hands. Prophylactic clipping may be valuable after ESD to prevent these complications, but large randomized trials are needed to determine efficacy for bleeding prophylaxis specifically [Citation58,Citation63,Citation64].

5.3. Competition

5.3.1. Suturing devices

Endoscopic suturing is a technique that closely resembles surgical stitching and largely has the same indications as clipping. A suturing device that is mounted onto the tip of the scope sutures the lesion margins together with needle and thread. Contrary to clips, endoscopic sutures provide an airtight full thickness closure and are able to close larger lesions [Citation62]. The OverStitch endoscopic suturing device (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tex, USA) is currently the only device approved for clinical use to place running or interrupted sutures. Although current research heavily focuses on suturing for treatment of upper GI surgical complications and obesity treatment, some experience in the lower GI tract has been reported [Citation65–Citation67]. Multiple technical limitations have been noted, among which the need of a double-channel endoscope, the need of an overtube and the lack of easy maneuverability [Citation65]. An endoscopic suturing device for a single channel endoscope has been developed in Japan, but is currently not commercially available [Citation68,Citation69]. Although suturing devices seem promising, further development and studies are needed in order to become truly competitive with clips.

5.3.2. Topical hemostatic agents

Clips are certainly not the only tool made for the treatment and prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding. A variety of other hemostatic products is available on the market. Topical hemostatic agents designed for endoscopic use include Hemospray (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA), Endoclot (EndoClot Plus, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), Purastat (3-D Matrix Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and Ankaferd (Immun İlaç Kozmetik Ltd. ŞTI., Istanbul, Turkey). Unfortunately, these agents have so far not been evaluated in large studies or compared head-to-head with clipping. Future research should determine the role of these topical agents in bleeding prevention and management.

6. Expert opinion

The development of ECDs has dramatically changed the approach to endoscopic hemostasis. The clip has made its way from the upper GI tract to the colorectum, where it has improved EMR safety by treatment and – potentially – prevention of complications. This has resulted in a reduced need for surgery for advanced adenomas. Its application is now being further expanded.

Novel advances in clipping during and after EMR will not only impact the approach in expert centers. EMR of large adenomas are increasingly part of standard care performed in non-expert hospitals. Therefore, there is a broadly shared interest in EMR-related issues such as the usefulness of prophylactic clipping after EMR of high-risk adenomas in the colon. This is illustrated by the various trials worldwide that are currently being conducted on this topic. We believe that prophylactic clipping has a definite role in daily practice in preventing delayed bleedings in high-risk EMRs, characterized by large flat or sessile lesions of more than 2 cm in the proximal colon, especially in case of anticoagulant use. Nevertheless, even when the evidence is in favor of prophylactic clipping, strict criteria for appropriate and safe use should be applied. For example, prophylactic clipping should only be performed after radical resections, in order not to bury leftover adenomatous tissue. Furthermore, the efficacy of clipping goes hand in hand with the used technique for clip placement. Targeted clipping of visible vessels for preventive reasons should be discouraged based on the available literature. Instead, the resection wound should be closed entirely when clipping prophylactically. From a technical point of view, we advise to keep a distance of 0.5–1.0 cm between adjacent clips. Cost-effectiveness studies are important in order to assure feasibility of implementation of this preventive measure. Based on the number of clips needed for effective closure, the number needed to treat and the prevented treatment costs for delayed bleeding, a more accurate calculation of the total costs of this intervention can be made. Ideally, endoscopists, health insurance companies, clip manufacturers and governmental agencies should collaborate in order to achieve optimal price models for clips and further optimize the adoption of PC in clinical practice. Currently, cheaper clips from Chinese manufacturers are increasingly being used, especially in low-income countries. Although this may be a good development, more data on these clips are desirable to ascertain if they are technically comparable to the mainstream clips and are of adequate quality and safety.

Additionally, an interesting question is whether clipping is always the best approach to achieve hemostasis and prevent delayed bleeding after EMR. Many other hemostatic agents and devices are currently being developed that could potentially compete with clips for bleeding treatment and prevention. A range of topical agents is available, such as Purastat gel, Hemospray, and Endoclot. As these agents are in various stages of testing, a head-to-head comparison with clips has not (yet) been performed. Currently, we believe that clips are superior to these topical agents for bleeding treatment and prophylaxis in high-risk large lesions. Nonetheless, a future role may certainly be anticipated for these agents in small lesions and in cases where clipping is challenging.

Lastly, current trends suggest that the focus of colorectal clipping research may shift from bleeding to perforation. The coming five years will determine if PC will be implemented in daily practice on a large scale and if this will have an effect on pricing of TTS clips. This may result in a new interest for closure techniques of large EMR-lesions and perforations with TTS clips. Simultaneously, novel closure techniques such as large-diameter clips and suturing devices will be further studied in the future. We believe that in the decades to come, a selection of these advanced endoscopic treatments will replace surgical closure of large EMR-related perforations in most cases.

Article Highlights

Clips are used after endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for the treatment and prevention of bleeding and perforation.

Complete closure of EMR lesions with TTS clips for the prevention of DB is possible with a distance between clips of 1 cm.

Although different TTS clips are comparable in terms of effective closure, Resolution clips (Boston scientific, USA) seem to have the longest retention duration.

Endoscopic closure of perforations should be attempted with TTS clips for small perforations and an OTSC for larger perforations up to 3 cm to prevent the need for surgical intervention.

In the next 5 years, daily practice of (prophylactic) clipping and subsequently clip pricing may change, which will likely determine the playing field for the new development of competing devices.

Declaration of interest

P. Siersema, A. Turan, and E. van Geenen are currently performing the CLIPPER trial on prophylactic clipping after EMR in the colon. P. Siersema also receives research support from Pentax (Japan) and is on the advisory board of MicroTech (China). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

One peer reviewer is a member of the Board of directors of Ovesco Endoscopy. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (124.5 KB)Supplementary Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Kretschmann J, et al. Trends in adenoma detection rates during the first 10 years of the German screening colonoscopy program. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):356–66.e1.

- Hayashi T, Yonezawa MTK. The study on staunch clip for the treatment by endoscopy. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1975;1975:92–101.

- Schurr MO, Hartmann C, Kirschniak A, et al. Experimental study on a new method for colonoscopic closure of large-bowel perforations with the OTSC (R) clip. Biomedizinische Technik. 2008;53(2):45–51.

- Carr-Locke DL. The history of clips in endoscopy. 2013. [cited 2019 Jan]. Available from: https://www.cookmedical.com/endoscopy/the-history-of-clips-in-endoscopy/.

- Wang TJ, Aihara H, Thompson AC, et al. Choosing the right through-the-scope clip: a rigorous comparison of rotatability, whip, open/close precision, and closure strength (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89(1):77-86.e1.

- Swellengrebel HA, Marijnen CA, Vincent A, et al. Evaluating long-term attachment of two different endoclips in the human gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2(10):344–348.

- Shin EJ, Ko CW, Magno P, et al. Comparative study of endoscopic clips: duration of attachment at the site of clip application. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(4):757–761.

- Bourke M. Endoscopic mucosal resection in the colon: a practical guide. Tech Gastrointest Endoscopy. 2011;13(1):35–49.

- An SB, Shin DW, Kim JY, et al. Decision-making in the management of colonoscopic perforation: a multicentre retrospective study. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2016;30(7):2914–2921.

- Saxena P, Ji-Shin E, Haito-Chavez Y, et al. Which clip? A prospective comparative study of retention rates of endoscopic clips on normal mucosa and ulcers in a porcine model. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(6):360–365.

- Ponugoti PL, Rex DK. Clip retention rates and rates of residual polyp at the base of retained clips on colorectal EMR sites. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(3):530–534.

- Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, et al. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49(3):270–297.

- Kantsevoy SV, Adler DG, Conway JD, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(1):11–18.

- Paspatis GA, Dumonceau JM, Barthet M, et al. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) position statement. Endoscopy. 2014;46(8):693–711.

- Burgess NG, Bassan MS, McLeod D, et al. Deep mural injury and perforation after colonic endoscopic mucosal resection: a new classification and analysis of risk factors. Gut. 2017;66(10):1779–1789.

- Tang SJ. Zipper clip closure of colonoscopic perforations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(4):867–869.

- Backes Y, Kappelle WFW, Berk L, et al. Colorectal endoscopic full-thickness resection using a novel, flat-base over-the-scope clip: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2017;49(11):1092–1097.

- Weiland T, Fehlker M, Gottwald T, et al. Performance of the OTSC system in the endoscopic closure of iatrogenic gastrointestinal perforations: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(7):2258–2274.

- Dinelli M, Omazzi B, Andreozzi P, et al. First clinical experiences with a novel endoscopic over-the-scope clip system. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5(3):E151–e6.

- Verlaan T, Voermans RP, van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Endoscopic closure of acute perforations of the GI tract: a systematic review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(4):618–28.e5.

- Voermans RP, Le Moine O, von Renteln D, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic closure of acute perforations of the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(6):603–608.

- Schmidt A, Riecken B, Damm M, et al. Endoscopic removal of over-the-scope clips using a novel cutting device: a retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2014;46(9):762–766.

- Weiland T, Rohrer S, Schmidt A, et al. Efficacy of the OTSC System in the treatment of GI bleeding and wall defects: a PMCF meta-analysis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2019;1–19.

- Bauder M, Meier B, Caca K, et al. Endoscopic removal of over-the-scope clips: clinical experience with a bipolar cutting device. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(4):479–484.

- Caputo A, Schmidt A, Caca K, et al. Efficacy and safety of the remOVE system for OTSC((R)) and FTRD((R)) clip removal: data from a PMCF analysis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2018;27(3):138–142.

- Burgess NG, Metz AJ, Williams SJ, et al. Risk factors for intraprocedural and clinically significant delayed bleeding after wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection of large colonic lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):651–61.e1-3.

- Metz AJ, Bourke MJ, Moss A, et al. Factors that predict bleeding following endoscopic mucosal resection of large colonic lesions. Endoscopy. 2011;43(6):506–511.

- Kim HS, Kim TI, Kim WH, et al. Risk factors for immediate postpolypectomy bleeding of the colon: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(6):1333–1341.

- Fahrtash-Bahin F, Holt BA, Jayasekeran V, et al. Snare tip soft coagulation achieves effective and safe endoscopic hemostasis during wide-field endoscopic resection of large colonic lesions (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(1):158–63.e1.

- Anastassiades CP, Baron TH, Song L. Endoscopic clipping for the management of gastrointestinal bleeding. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2008;5(10):559–568.

- Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Lai LH, et al. Endoscopic clipping versus injection and thermo-coagulation in the treatment of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2007;56(10):1364–1373.

- Binmoeller KF, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Endoscopic hemoclip treatment for gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 1993;25(2):167–170.

- Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima T, et al. Hemoclipping for postpolypectomy and postbiopsy colonic bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(1):37–41.

- Chou KC, Yen HH. Combined endoclip and endoloop treatment for delayed postpolypectomy hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(1):218–219.

- Wedi E, Gonzalez S, Menke D, et al. One hundred and one over-the-scope-clip applications for severe gastrointestinal bleeding, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(5):1844–1853.

- Kirschniak A, Falch C, Kirschniak N, et al. Clinical applications and experimental experiences - a systematic review. Endoskopie Heute. 2011;24(3):195–200.

- Schmidt A, Golder S, M G, et al. Over-the-scope clips are more effective than standard endoscopic therapy for patients with recurrent bleeding of peptic ulcers. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):674–86.e6.

- Liaquat H, Rohn E, Rex DK. Prophylactic clip closure reduced the risk of delayed postpolypectomy hemorrhage: experience in 277 clipped large sessile or flat colorectal lesions and 247 control lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(3):401–407.

- Bahin FF, Rasouli KN, Williams SJ, et al. Prophylactic clipping for the prevention of bleeding following wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection of laterally spreading colorectal lesions: an economic modeling study. Endoscopy. 2016;48(8):754–761.

- Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(3):446–454.

- Choung BS, Kim SH, Ahn DS, et al. Incidence and risk factors of delayed postpolypectomy bleeding: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(9):784–789.

- Matsumoto M, Fukunaga S, Saito Y, et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic resection for large colorectal tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(11):1028–1034.

- Kwon MJ, Kim YS, Bae SI, et al. Risk factors for delayed post-polypectomy bleeding. Intest Res. 2015;13(2):160–165.

- Boumitri C, Mir FA, Ashraf I, et al. Prophylactic clipping and post-polypectomy bleeding: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29(4):502–508.

- Shioji K, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Prophylactic clip application does not decrease delayed bleeding after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(6):691–694.

- Dokoshi T, Fujiya M, Tanaka K, et al. A randomized study on the effectiveness of prophylactic clipping during endoscopic resection of colon polyps for the prevention of delayed bleeding. Biomed Res Int. [Internet]. 2015; 2015:490272. Available from. : http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/361/CN-01110361/frame.html/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4332985/pdf/BMRI2015-490272.pdf

- Zhang Q, Han B, Xu J, et al. Clip closure of defect after endoscopic resection in patients with larger colorectal tumors decreased the adverse events. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015;82(5):904–909. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/268/CN-01258268/frame.html/https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0016510715023160/1-s2.0-S0016510715023160-main.pdf?_tid=6efef619-ee80-448a-9d21-0773e075b863&acdnat=1535113544_a6091286d4b9ff17eee05e6569c71619

- Feagins LA, Nguyen AD, Iqbal R, et al. The prophylactic placement of hemoclips to prevent delayed post-polypectomy bleeding: an unnecessary practice? A case control study. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(4):823–828.

- Feagins L, Harford W, Halai A, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of prophylactic hemoclipping for preventing delayed post-polypectomy bleeding in patients with large colonic polyps: an interim analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017;85(5 Supplement 1):Ab122–ab3. Available from http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/520/CN-01430520/frame.html

- Albeniz E, Fraile M, Ibanez B, et al. A scoring system to determine risk of delayed bleeding after endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(8):1140–1147.

- Matsuda T, Fujii T, Emura F, et al. Complete closure of a large defect after EMR of a lateral spreading colorectal tumor when using a two-channel colonoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(5):836–838.

- Sakurai T, Adachi T, Kono M, et al. Prophylactic suturing closure is recommended after endoscopic treatment of colorectal tumors in patients with antiplatelet/anticoagulant therapy. Oncology. 2017;93(Suppl 1):27–29.

- Ivekovic H, Vrzic D, Bilic B, et al. Release and re-hook: a novel method with combined use of clips and nylon snare to close a colonic defect after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2015;47(Suppl 1):E545–E546.

- Fujii T, Ono A, Fu KI. A novel endoscopic suturing technique using a specially designed so-called “8-ring” in combination with resolution clips (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(6):1215–1220.

- Lucchini C, Rosa-Rizzotto E, Guido E, et al. “Lucky loop”: a variant of an endoloop + clip wound closure technique after colonic defiant polyp removal. Digestive Liver Dis. 2015;2:e107.

- Pellise M, Desomer L, Burgess NG, et al. The influence of clips on scars after EMR: clip artifact. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(3):608–616.

- Bittinger M, Messmann H. Endoscopic therapy with a novel multiple clip applicator (ClipMaster3) in the upper and lower GI-tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(5):AB146–AB.

- Yamasaki Y, Takeuchi Y, Iwatsubo T, et al. Line-assisted complete closure for a large mucosal defect after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection decreased post-electrocoagulation syndrome. Dig Endosc. 2018;30(5):633–641.

- Wedi E, Orlandini B, Gromski M, et al. Full-thickness resection device for complex colorectal lesions in high-risk patients as a last-resort endoscopic treatment: initial clinical experience and review of the current literature. Clin Endosc. 2018;51(1):103–108.

- Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47(9):829–854.

- Fujiya M, Tanaka K, Dokoshi T, et al. Efficacy and adverse events of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of colon neoplasms: a meta-analysis of studies comparing EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(3):583–595.

- Kantsevoy SV, Bitner M, Mitrakov AA, et al. Endoscopic suturing closure of large mucosal defects after endoscopic submucosal dissection is technically feasible, fast, and eliminates the need for hospitalization (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(3):503–507.

- Fujihara S, Mori H, Kobara H, et al. The efficacy and safety of prophylactic closure for a large mucosal defect after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(1):85–90.

- Harada H, Suehiro S, Murakami D, et al. Clinical impact of prophylactic clip closure of mucosal defects after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5(12):E1165–e71.

- Pham BV, Raju GS, Ahmed I, et al. Immediate endoscopic closure of colon perforation by using a prototype endoscopic suturing device: feasibility and outcome in a porcine model (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(1):113–119.

- Sharaiha RZ, Kumta NA, DeFilippis EM, et al. A large multicenter experience with endoscopic suturing for management of gastrointestinal defects and stent anchorage in 122 patients: a retrospective review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):388–392.

- Stavropoulos SN, Modayil R, Friedel D. Current applications of endoscopic suturing. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7(8):777–789.

- Mori H, Kobara H, Kazi R, et al. Balloon-armed mechanical counter traction and double-armed bar suturing systems for pure endoscopic full-thickness resection. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):278–80.e1.

- Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, et al. Current status and future perspectives of endoscopic full-thickness resection. Digestive Endosc. 2018;30:25–31.