ABSTRACT

A major attraction in Arctic tourism is the presence of indigenous cultures. However, many tourists have only limited opportunities to access indigenous culture and sites, as long as they are not spatially and temporally fixed. This puts museums at the center of attention and gives them a core role in portraying and interpreting indigenous heritage. A dual role with the responsibility to collect, preserve, use, and develop heritage while at the same time appealing to various visitor groups is challenging, not least in a time of Arctification, luring new visitor groups with various touristic imaginaries to the North. This article reports on an assessment of two indigenous museums in Arctic Sweden. The research reveals that the responsible managers at the museums are aware of the dual role of museums, and need to navigate in a complex environment of local and global expectations based on preconceived notions. The museums are important nodes, and contribute to place-making in peripheral localities in the North.

Introduction

The relationship between tourism and indigenous peoples has been a focus of academic research for quite a while, having been reviewed in numerous articles, book chapters, and several major book publications (e.g. Butler & Hinch, Citation1996, Citation2007; de Lima & King, (Citation2018; Ryan & Aicken, Citation2005). In this context, indigenous tourism has been seen as the ‘ … integration of indigenous people into a global culture on the one hand, while encouraging indigenous communities to protect and enhance local advantages that may give them a competitive advantage […] on the other … ’ (Hinch & Butler, Citation2007, p. 2). This dual role comes at a price. Debates in the above-mentioned academic publications indicate that tourism is seen both as a threat to indigenous peoples’ cultures and environments, and as an opportunity for economy, cultural rejuvenation, and empowerment (Müller & Huuva, Citation2009). However, global generalizations should be made with care, as the preconditions for indigenous peoples to achieve a desired future vary greatly among different countries around the world. This has been addressed by Smith (Citation1996), for example, who argues in her 4H approach that the varying preconditions, experiences, and access to history, heritage, habitat, and handicrafts (i.e. the 4Hs) influence why and how indigenous peoples engage in and get involved in tourism. In a similar mission, Hinch and Butler (Citation2007) suggest an indigenous tourism system model that acknowledges the global variety. In accordance, indigenous tourism is embedded in complex physical, political, economic, and social environments, and is influenced by indigenous and non-indigenous stakeholders on different geographical scales with various ambitions and aspirations. Particularly tourism trade, government, and media are identified as powerful forces influencing how cross-cultural interactions unfold.

Another important element in an indigenous tourism system is indigenous tourism attractions. Although the availability of these attractions is often taken for granted and is rather discussed in relation to how to limit access (Zeppel, Citation2006), this is not the case everywhere. For example, Müller and Pettersson (Citation2001) argue that the availability of indigenous tourism resources to a generalist audience is limited, particularly when including interpretation for tourists. This applies not least in their studies of the Sámi, a largely well-integrated indigenous minority culture in the Nordic countries and Russia. Historically, many Sámi have been involved in nomadic reindeer husbandry and, thus, built and preserved material cultural expressions that can be presented on site are limited (Ljungdahl, Citation2012; Sametinget, Citation2022). In such a context, museums become important touristic attractions since they make a culture often hidden for the tourist gaze accessible at predetermined venues and opening hours (Müller & Pettersson, Citation2001). However, museums usually do not define themselves as primarily tourist attractions or even tourism stakeholders; instead, their role entails collecting, preserving, and presenting material evidence of the historical development of people and environment. This assignment is related to the overall idea of emancipation and popular education (Bennett, Citation2018; Hooper-Greenhill, Citation1992). It has sometimes entailed an uneasy relationship between museums and tourism, whereby non-commercial popular education and documentation ambitions collide with commercial and at least superficially hedonic tourist consumption (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Citation1998). This becomes particularly obvious in a context in which this relationship is overlaid with a post-colonial situation; here, museums not only portray indigenous peoples but also try to deal with a history of uneven relations, exploitation, violence, and cultural repression. Global tourists may themselves hold such historical, or even current, experiences from the same or a different cultural context.

While studies on the role of museums in relation to indigenous heritage are widely available (e.g. Horwood, Citation2018; Johansson & Bevelander, Citation2017; Magnani et al., Citation2018; Spangen, Citation2015), this is less often the case in relation to tourism. Thus, this article contributes a critical assessment of the role of indigenous museums as part of regional tourism supply. The purpose of the article is to analyze how indigenous museums cope with seemingly diverging expectations and translate this into exhibitions and strategies. Here, this is done focusing on two indigenous Sámi museums in northern Sweden, a recently rapidly developing peripheral destination with increasingly global appeal (Müller, Citation2015; Varnajot, Citation2020).

As institutions, museums are inevitably political and ideologically charged places that communicate through symbolic representation and targeted messages (Bennett, Citation1995, Citation2004; Gray, Citation2015; Karp & Lavine, Citation1991). For the visitor, the entire museum, regarding environment, place, building and exhibition, can be interpreted as a staged story or a narration (MacLeod et al., Citation2012; Psarra, Citation2009). We have to some extent been inspired by such theoretical approaches for this study. From that point of view, who controls the museum agenda becomes pivotal and indeed, even in relation to indigenous tourism, an indigenous control is considered as crucial (Hinch & Butler, Citation2007). Hence, as Weaver (Citation2010) notes, the taking over of touristic resources by indigenous peoples contributes to alter coloniality, or the patterns of a colonial relationship. However, in strategic theoretical terms, we have deliberately left out the phenomenological museum analysis, which is based on factors such as spatiality, modality, and semiotics, as well as own sense experience as an empirical base for contextualized conclusions. We acknowledge, however, that even intangible cultural heritage is increasingly utilized for touristic commodification, which contests authenticity and consecutively sustainable development (Kim et al., Citation2019). For this study, we are working more in a museum studies tradition directed towards analyzing factors that include cultural politics, spatial and symbolic narration, as well as its cultural theoretical implications.

Indigenous tourism and peripheries

Tourism is frequently identified as a potential livelihood, particularly in peripheral areas suffering from structural challenges related to economic and demographic development (Hall, Citation2007a; Hall & Boyd, Citation2005; Müller, Citation2011). It has been portrayed, albeit not without criticism, as an opportunity for indigenous populations to partake in business and, in addition to providing direct economic incomes, it has been argued that it could benefit indigenous peoples through the dissemination of knowledge about indigenous issues to interested tourists (Ruhanen & Whitford, Citation2019; Walker & Moscardo, Citation2016). In many cases, members of indigenous communities have embraced this idea and public schemes have supported indigenous tourism ventures in various ways to diversify indigenous and peripheral economies (Leu, Citation2019; Leu et al., Citation2018; Whitford & Ruhanen, Citation2010, Citation2016). This has created indigenous and non-indigenous expectations regarding the impact of tourism on local livelihoods.

A core message of Smith’s (Citation1996) 4H approach and Hinch and Butler’s (Citation2007) system model is the stress on the complexity and multiplicity of stakeholders involved in the formation of indigenous tourism. Hinch and Butler characterize this by highlighting the role of the physical, political, economic, and social environment framing the indigenous tourism production, and even in Smith’s 4H approach, this is recognized as part of the habitat and history of a destination. This contrasts with a previous situation in which indigenous attractions were available at ethnographic museums in urban cores. Today, improved transport opportunities enable tourists to visit even remote indigenous homelands, a step that Weaver (Citation2010) sees as a stage of a development away from a purely colonial relationship. In the following stage, Weaver argues, indigenous people take control over tourism, which is currently an ongoing albeit thorny process, even in the Arctic regions (Olsen et al., Citation2019; Viken & Müller, Citation2017; Zhang & Müller, Citation2018). For example, analyzing a market fair in northern Sweden, Müller and Pettersson (Citation2006) noted that it was an important arena for negotiating what is and is not acceptable in indigenous tourism. In this context, mediation contributes to objectifying and stereotyping indigenous peoples. Similarly, debates on authenticity in indigenous tourism further underline the contested nature of indigenous tourism (de Bernardi, Citation2019; Kramvig, Citation2017; Viken & Müller, Citation2017). To explain this, Smith (Citation1996) points to indigenous peoples’ sometimes agonizing relationships with the dominant society, implying a shifting willingness to engage in tourism business. While this affects the overall availability of indigenous tourism products, even different kinds of limitations constraining access to indigenous attractions and topics in time and space serve as strategies for balancing diverging expectations and desires among stakeholders (Zeppel, Citation2006).

Consequently, indigenous tourism products are not always available. Applying Smith’s typology, Müller and Pettersson (Citation2001) argue that habitat is the most accessible dimension of indigenous tourism. This is followed by variations of staged experiences that are available at predetermined places and times (Hinch & Delamere, Citation1993; Vladimirova, Citation2017). Few tourists access more exclusive products focusing on the everyday life of indigenous peoples. Instead, attractions that are available at fixed venues and times are preferable to a generalist audience that sees the indigenous as an integrated part of a wider tourism product that, in a peripheral context, often contains various kinds of wilderness experiences (Hall & Boyd, Citation2005). However, this should not be misinterpreted: Even tourists who consume tours and shows may have a contemporary perception of indigenous cultures (Abascal, Citation2019).

The peripheral locations of indigenous tourism mirror the pathways of colonial processes, integrating previously ‘empty’ territories into global economic and political networks, and in doing so, defining indigenous areas or their remains as peripheries. As such, these areas are typically disadvantaged because of, for example, a lack of power over decision-making, dependence on a small number of extractive industries, or a lack of infrastructure, capital, and educational facilities (Botterill et al., Citation2000; Hall & Boyd, Citation2005; Hall, Citation2007a; Müller & Jansson, Citation2007). Furthermore, distance decay implies that tourist trips to the periphery require time and money, resulting in small tourist volumes (Hall, Citation2005). Thus, a livelihood can be made by offering high-quality products with great revenues or by having tourism as just one of several occupations. Despite this, tourism development has often been a government response to and remedy for peripheral challenges (Jenkins & Hall, Citation1998). This applies to indigenous peoples in peripheries as well, particularly since traditional livelihoods are contested by modern development and alternative occupations in situ are rare (Heldt Cassel & Maureira, Citation2017; Müller & Hoppstadius, Citation2017). Hence, government and development agencies have pushed indigenous peoples toward displaying and commodifying indigenous cultures for tourism and development purposes (Niskala & Ridanpää, Citation2016). Indigenous culture has also sometimes been used by others to sell the periphery, which has triggered a debate on the ethical aspects of indigenous tourism development as well (Belder & Porsdam , Citation2017; Olsen et al., Citation2019).

It should be mentioned that diverging experiences can be seen in different geographical settings. In the Nordic case, where indigenous Sámi are not excluded from other labor markets, a recent OECD report (Citation2019) identifies tourism development as a means for diversifying indigenous economies and improving livelihood opportunities. While Leu and Müller (Citation2016) show that tourism is indeed a prominent diversification strategy among Swedish Sámi reindeer herders, Müller and Hoppstadius (Citation2017) point out that employment in tourism is far from being the sole option for indigenous people in the Nordic welfare states. Considerations involving cultural survival, as well as an interest in working with hospitality and in being able to use indigenous skills, were other reasons given for working in the tourism industry (Leu, Citation2019; Leu et al., Citation2018). Hence, one can note that indigenous peoples do not need to be targets of a deterministic development. Instead, they have the agency to choose whether and how to engage in tourism (Müller & Hoppstadius, Citation2017; Viken & Müller, Citation2017).

In an indigenous tourism system, museums play several important roles (Timothy & Boyd, Citation2003). Fraser (Citation2022) demonstrated these multiple roles in relation to an ethnic museum in China. For example, he notes that the establishment of an ethnic museum entailed increased minority participation, a genuine cultural engagement also among young people, as well as new livelihood opportunities related to tourism. Furthermore, museums are attractions accessible at predetermined places and times, offering ready-made interpretations of indigenous culture to generalist as well as specialized tourists (Pettersson, Citation2002). At the same time, they are important elements of the destination’s supply, contributing to its overall attractiveness. Museums are influential in the social construction and representation of the destination and its (indigenous) population as well, and are thus also of interest to local populations and other indigenous and non-indigenous stakeholders with a vested interest in the region. This is not without risk, as public funding obviously influences how heritage is constructed and communicated (de la Maza, Citation2016; Hall, Citation2007b). However, the core assignment of museums is to collect, document, research, manage, and display the history of a region, people, time, or phenomenon, and contribute to heritage (Macdonald, Citation2011). But, as for example the Canadian anthropologist and museologist Ryker-Crawford points out, this heritage is also a plastic tool for identity formation amongst the displayed culture itself:

Indigenous peoples are becoming active participants in museums and cultural centers across the world. They are utilizing these spaces as strategic tools for community building, group support and cultural engagement, as well as arenas to convey their stories and histories. (Ryker-Crawford, Citation2017, p. 161)

Combining this with the seemingly more hedonic aspirations of tourism may be a challenge to be considered and dealt with. Hence, as Ryker-Crawford notes, the inclusion of indigenous stakeholders is more than a superficial adaptation. Instead, it is

… a fundamental shift in the philosophical mind-set of museums, away from the idea that museums have the legal authority to hold their collection for the benefit of the broader public, and towards the idea that museums have an ethical trust obligation to the cultures and peoples whose material they collect and exhibit, and that this obligation includes support, collaboration, and interaction with these peoples. (Ryker-Crawford, Citation2017, p. 20)

How this unfolds in the case of two indigenous museums in Sweden will be presented in the remainder of the article.

Methodology

Methodologically, the study is based on a hermeneutic interpretation of observations, conversations, information materials, and field notes collected primarily during a field visit in October 2020. A hermeneutic approach accepts subjectivity as a tool to enrich seemingly objective observations and facts (Babich, Citation2017; Shapin, Citation2012). Accordingly, past and present are constantly negotiated in relation to temporal and cultural conditions. This does not imply a rejection of systematic application of various methods but, highlights that such investigations always are dependent on individual assessment and interpretation. Hence, the focus of a hermeneutic approach is interpretation for understanding rather than measuring data.

Observation is an important research method in social sciences and simultaneously one of the most diverse. Ciesielska and colleagues (Citation2018) distinguish three types of observation, namely participant observation, non-participant observation, and indirect observation. These types can be used in different ways and even be combined with each other. Here, a participant observation has been applied. Being researchers and museum visitors at the same time underlines that the different roles occur simultaneously, which implies the hermeneutic characteristics of the chosen approach.

The involved researchers have during the recent decade on several occasions visited the surveyed museums and even the communities where they are located. During the field visits in 2020 one day was spent at each museum. After having gained an overall understanding of the museums, the researchers went individually through the exhibitions and observed and documented their impressions through notes and photographs. The result of the data collection were more than 120 photographs and related field notes. This allowed for interpreting not only texts but also artefacts exhibited in the museums. Even the placement and spatial compilations of artefacts provided information for interpretation. The procedure enabled independent assessment of the exhibitions allowing the researchers to compare impressions and interpretations after the visit when common observations were identified. The observations and the following interpretation were done in line with established methods where observations were compared and categorized inductively (Hodder, Citation1994). Furthermore, the researchers engaged in conversations with museum curators and administrators at the two sites as an additional source of information, and documented this with field notes as well.

The researchers also benefitted from previous visits to the museums and an overall knowledge of the places and environments they are imbedded in as well as previous studies of indigenous tourism and museums. This deeper understanding of the broader context of this study has been important in the interpretation of the results. Finally, the manuscript was shared with the managers of the museums to ensure the correctness of facts and the appropriateness of interpretations.

The geographical setting

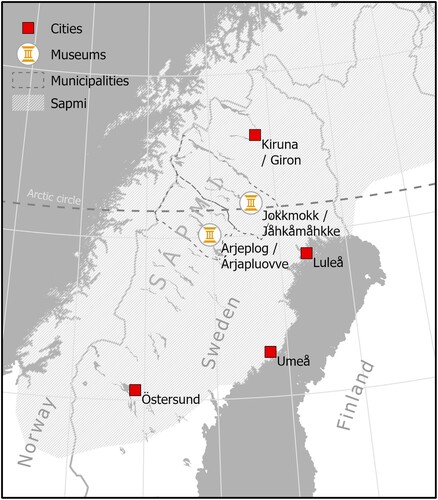

The chosen museums are both located in the inner parts of northern Sweden, a region referred to as Lapland and today, with recognition of the longstanding indigenous presence, also as Sápmi, the Sámi word for the region (). Long having been populated, the region attracted national interest in the nineteenth century when natural resources such as fur, timber, and minerals became accessible (Keskitalo, Citation2019). The resulting development has been characterized as colonization, though it is important to note that, in contrast to elsewhere, this has not been in the form of a frontier colonization. Instead, Bylund (1954) labels the process internal colonization, acknowledging the fact that it predominantly implied an economic-geographical transition from Sámi nomadic reindeer herding to sedentary livelihoods and settlements based on farming, hunting, and industrial work. Hence, most of the settlers were of Sámi descent, but eventually a Swedish policy deprived most of them of their Sámi identity (Lundmark, Citation2008). This created a schism between reindeer-herding Sámi and those not involved in reindeer herding, which is still prevalent in Sámi society today. It also created a dynamic, heterogenous population in which ethnicity and identity are far from being clear-cut categories. This makes even questions related to indigenous tourism complex matters, as it is not necessarily appreciated by everyone (Müller & Huuva, Citation2009).

Figure 1. The geographical location of Ájtte in Jokkmokk/Jåhkåmåhkke and Silvermuseet in Arjeplog/Árjapluovve.

Ájtte is a public museum in Jokkmokk/Jåhkåmåhkke, a small town located on the Arctic Circle. The museum opened in June 1989, and has just over 20 employees. It is run by a foundation formed in 1983 by the Swedish state, the Norrbotten County Council, Jokkmokk Municipality, the Swedish Sámi National Association, and Same Ätnam, a Sámi cultural organization. Originally, the Swedish state had intended to open a museum focusing on national parks, but the municipality wanted a museum focused on the Sámi. The ultimate result was a compromise, with Ájtte being financed by compensatory funds from hydropower generation in the region, due to their destruction of historical migration routes for Sámi reindeer herding. The official mandate of the museum is to specialize in the mountain world’s culture and nature, and it is the main museum of Sámi culture in Sweden (SOU, Citation2009). Today, the national park focus has been toned down since a nature interpretation center has opened at the park’s entrance.

Silvermuseet (Eng. Silver Museum) is a municipal museum in Arjeplog/Árjapluovve, a neighboring town roughly 200 km west of Jokkmokk/Jåhkåmåhkke. The museum’s major feature is a collection of Sámi silver assembled by Einar Wallquist, a twentieth-century provincial physician in the area. However, the museum does not identify itself as a primarily indigenous museum; rather, it aims to represent Arjeplog/Árjapluovve as a place where different cultures meet. Hence, even the settler culture has been given a prominent place on the premises.

Both Jokkmokk/Jåhkåmåhkke and Arjeplog/Árjapluovve have recently experienced population decline, an aging population, and selective outmigration of the young (Müller & Brouder, Citation2014). This has caused the local government to seek alternative sources of livelihood, identifying not least nature-based tourism as a promising sector. The designation in 1996 of parts of the area, Laponia, as a combined nature/culture World Heritage Site, recognizing the Sámi heritage and the outstanding mountain landscape, further contributed to this ambition. Indeed, Laponia is co-managed by Sámi organizations and the public sector, indicating attempts to increase official Sámi control over the Sámi homelands (Stjernström et al., Citation2020).

The museums

For an overwhelming majority of tourists, the first physical encounter with an indigenous culture – in this case, the Sámi – is mediated through museum exhibitions. Therefore, museums are of great importance as a ‘guide’ for the visitor’s first impression of and continued relationship with the culture. The two prominent museums in this study are pivotal regarding Sámi representation: Ájtte in Jokkmokk/Jåhkåmåhkke, and Silvermuseet in Arjeplog/Árjapluovve. Both hold eminent positions in the local built environment, due to their architecture and location (). There are, of course, different criteria for determining a museum’s prominence in relation to the studied theme and field. However, in terms of the size of the collections when it comes to inventory numbers related to Sámi objects, our selected museums are first and third nationally, while Nordiska museet (‘the Nordic Museum’) in Stockholm can be found in second place (Kuoljok, Citation2008). The selected museums have a pronounced, though not exclusive, profile involving specific Sámi culture, which means that together they should be regarded as the main Swedish museums for the dissemination of Sámi cultural heritage.

What does the visitor encounter, with an expectant tourist gaze in her luggage, when visiting these museums? It should be clarified at the outset that the two museums differ in terms of profiling: Silvermuseet has gone from a lay-focused local history museum to an expanded and gradually professionalized museum, where academic research as well as guided tours and cultural environment activities are now on the agenda. Nevertheless, its appearance as an integrative museum of the local area and environment remains very clear (which is professionally intended). The museum’s mission and didactic focus are thus calibrated on the site as an arena for dynamic cultural activity, from ancient times to the present.

Ájtte, on the other hand, is the main museum of Sámi culture in Sweden. The museum also functions as an information center for mountain tourism, and includes a botanical mountain garden in Jokkmokk/Jåhkåmåhkke as well. With this, Ájtte has said that its primary focus and mission is to represent Sámi cultural heritage and to work for a deeper and nuanced picture of the Sámi, seen both outward in relation to the general visitor and inward in relation to their own ethnicity. The latter is not an easy balancing act, as Sámi ethnicity and culture throughout the twentieth century have been shaped by both a colonial distinctive rhetoric from state and classical academia as well as by an internal activist identity policy and lately a decolonial activist academia, both of which have emphasized nomadic reindeer husbandry and the image of the Sámi (Andresen et al., Citation2021). This is the case, even though all parties are now aware that Sámi culture and identity are also shaped and have been characterized by other forms of livelihood, such as hunting, fishing, and farming. As a result, a large part of Sámi culture and cultural heritage has been mutilated and distorted. Ájtte has now, likely for this reason, significantly toned down its focus on reindeer husbandry as the prescribed singular culture-bearing factor – today, its exhibitions convey a more complex picture of a close-to-nature and multifaceted culture, in which reindeer husbandry has certainly always been central.

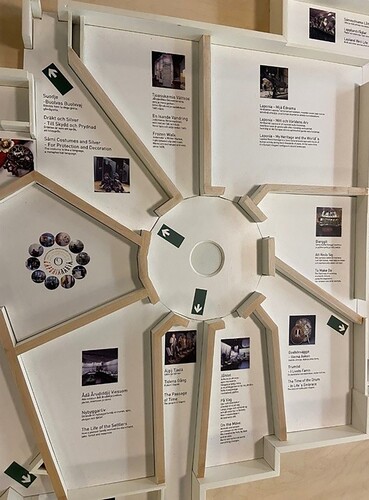

As Ájtte has Sweden’s largest collection of deposited Sámi objects, its curators have good opportunities to convey the intended breadth and complexity. The solution has therefore been to offer the visitor many thematically constructed exhibition sections, all of which can be reached via a circular hub of optional entrances. In this way, one has avoided locking the visitor into following a singular, teleological development history, which is typically reproduced in national museums around the world (Knell et al., Citation2011). At the same time, the spatial setup resembles the organization of a reindeer corral ().

Figure 3. Scheme of Ájtte’s exhibition halls resembling a reindeer corral (Photo: Richard Pettersson).

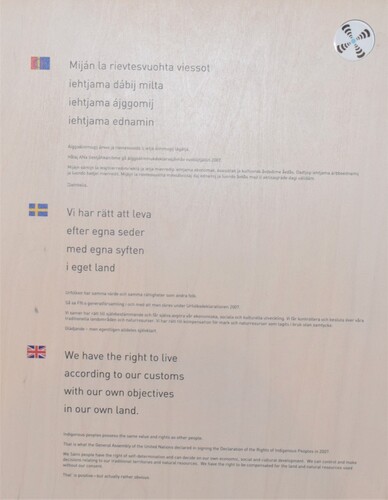

The form of address at the museum is a welcoming personal pronoun: It is ‘we’ (the Sámi) who invite ‘us’ (visiting tourists) to take part and learn. Alternatively, if the visitor himself is Sámi, the museum works for cultural empowerment and enlightenment (Kuoljok, Citation2008). Hence, interpretation in Lule Sámi, the regional Sámi language, is equally available despite the relatively small number of Sámi who are able to speak this language (). Ájtte’s no less than 18 exhibition sections reflect industry and technology, crafts and costumes, trade, geography and landscape, as well as anthropological culture. As with Silvermuseet, Ájtte has a clear awareness of the complexity of categorizations; Sámi are also Swedes, and are today typically as modern as all other Westerners. But conveying such nuance is a challenge both internally to one’s own ethnicity and externally to visiting tourists, who expect representations of the Sámi cultural character. Too great a focus on distinctiveness and cultural exclusivity (Scylla) thus risks striking back at the ambition to also anchor the Sámi in our time. And too great a focus on the resemblance to the global modernity of the ‘majority culture’ (Carybdis) risks diluting the museum’s core mission.

Correspondingly, Silvermuseet has chosen to tone down overly obvious references to specifically Sámi culture where the ground-floor exhibition ‘Traces’ about Arjeplog/Árjapluovve’s prehistory is depicted. The brochure states: ‘In Traces, messages are conveyed through thousands of years. Stories about the lives, insights, and experiences of the hunters and fishermen who came here when the ice sheet retreated.’Footnote1 The narrative grip here is to poetically convey the stories the objects tell: ‘The stone spearhead can tell about the hunter’s agile leap toward his prey or the stonemason’s insight into the hidden properties of the stones.’ The museum’s mission requires the visitor to engage. The brochure assures and urges: ‘You can choose which story you want to listen to.’ Still, as the museum’s management is aware of the role of Sámi heritage for the museum and community, an ambition is thus to focus on and portray the Sámi heritage in the Pite River valley, which also results in interpretation being available in the local Pite Sámi language. Overall, interpretation signage is more limited here, which creates a certain risk that exhibitions are only experienced bodily and visually. However, as the management noted, it is challenging to provide texts for diverging target groups and to do so on a level that conveys the complexities of heritage, including to tourists with a non-specialist interest, without becoming too generalizing or shallow.

Silvermuseet’s exhibition departments, however, are generally divided more traditionally according to a segregated order between, for example, everyday Sámi tools versus the equivalent from new settlers. But for both museums, the historical perspective tends to stop at the transition to late modern society. Developments since the 1970s, with industrial, cultural, and geopolitical change characterizing and contesting indigenous issues and debate, are themselves likely still too charged to be portrayed more permanently at either of the museums.

Regarding the Sámi as indigenous peoples, both museums have a delicate task, balancing between an over similarity and thus flattening relationship with the majority culture on the one hand and an overly strong emphasis on distinctiveness on the other, which creates a risk of locked-in essentialism. Conceptually, and from old tradition, the Sámi are distinguished from ‘Swedes’ in references. There is obviously an inevitable didactic need to, after all, highlight ethnic distinctiveness, not least in the exhibitions. As the historian Bruyoni Onciul has pointed out: ‘If essentialism is a given, then it can be useful to use it consciously and strategically to achieve certain goals’ (Onciul, Citation2015, p. 165). But at both museums, one is fully aware of the complexity of the references; not least when the chronology approaches modern times.

From previously conveying a rather sharp distinction between settlers and Sámi, the representations are now balanced by a conscious hybridization. In a brochure from Silvermuseet, for example, the historical narrative is nuanced: It is suggested here that the porous category ‘Swedes’ did not become permanent settlers in Arjeplog/Árjapluovve until the end of the eighteenth century; but at the same time, the brochure clarifies that such new settlements, starting in 1720, initially had Sámi origins – simply consisting of Sámi who converted to settlers to be able to enjoy 15 years of tax exemption (one of the conditions for settling) – ceased nomadic reindeer husbandry, and conducted some cultivation. In the same way, the texts in Ájtte’s corresponding section Nybyggarliv (Eng. Settler life) state that many Sámi also chose the livelihood of a settler as a way of life. The exhibition brochure tells us:

For several thousand years the people lived here as hunters, fishermen, and reindeer herders. But about 300 years ago, something new began. Some settled down, tried to grow grain and potatoes, and got cows, goats, sheep, and maybe even a horse. The settlers were Sámi, Swedes, or Finns, and a mixed culture arose.

The category of settlers therefore appears as a hybridization or creolization between the Sámi and the majority Swedish. The settlers appear as the link between a tradition-driven indigenous culture versus generally modern Swedishness, lacking clear identity. For both museums, the exhibition spaces about the Sámi that are dedicated to conveying ethnic distinction are thereby calibrated. What is clear about the Sámi is that the chronological determinations seldom follow a linear account. The Sámi, as an ethnic cultural quality, appears to be immersed in a pre-industrial deep and somewhat ‘timeless’ history. This also suggests an inevitable dramaturgy: The Sámi, because of their pre-modern character and distinctiveness, have become increasingly threatened and corrupted by the onset of modernity. In ethnology, this relationship has been referred to as deevolutionism; that is, the analytical view of culture is juxtaposed against origin and pre-modernity (Lilja, Citation1996). At the same time, at least Ájtte has consciously worked to counteract such logic, for example by reproducing Sámi reindeer herders dressed in modern work clothes and using modern means of transport. The mission here seems to be to show how traditions, crafts, and not least language as ‘the central marker of identity/ethnicity’ have survived but have also been modified in late modern society (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Citation2008, p. 82). This is in line with previous studies where the use of indigenous language has been shown to challenge otherwise existing language hegemony (Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2016).

Present and history

Indeed, both museums rather skillfully balance between genre-specific expectations of ethnic distinctiveness and the obvious fact that the Sámi in today’s everyday life, in many ways, can hardly be distinguished from the majority culture.

Not least Ájtte’s extensive and well-developed multimodal exhibition sections are likely to provide the visiting tourist with experiences that generate both learning and continued curiosity about perhaps also seeing and experiencing Sámi culture up close. Whether this leads to a greater interest in encountering Sámi culture even outside the museum premises, though, is beyond the scope of this study. It can be noted, however, that Silvermuseet hosts the local tourist information center, offering further guidance to Sámi companies in the vicinity. Very well-assorted museum shops offer popular and scientific literature for further studies of the culture and history of the region.

The complexity of representing and nuancing the images of Sámi culture also loads the inevitable binary contrast against a majority culture. What do the Sámi, the settler culture, and the Swedish majority culture mean in these relational contexts? Hence, both museums have to contend with a two-part logic of time, whereby the representation of the Sámi tends to reproduce a cyclical conception of time while the corresponding representation of settlers and contemporaries follows common linear development logic, from older and more primitive to younger and more advanced. The Sámi-linked cyclical time logic is linked to nature and the seasons, as well as the instinct-driven existence of animals (especially reindeer). The indigenous Sámi people are thus a ‘natural’ people, portrayed in accordance with the animals’ and nature’s deep time-historical, almost geologically situated logics. As a result, the Sámi appear as almost timelessly static. What is deliberately missing here is the common genesis-driven narration and reverence for the very oldest, the originals – the cultural seeds that initiated evolutionary development. The Sámi exhibition departments consistently lack the showpiece object, the Mona Lisa, that must be regarded and revered as a materialized petrification of cultural essence. Instead, the intangible tradition, know-how, and succession are celebrated. The cultural heritage does not lie as much in designated material archetypes and authentic originals as in insights and knowledge for carrying on traditions and knowledge from pre-industrial times. Because of this, exhibition sections on contemporary Sámi handicrafts coexist, without a change of context, in direct connection with the corresponding historical ones. Also, the costumes, which are displayed at both museums according to classical ethnographic typology, could just as easily be reproductions. These artefacts have a liminal status between the unique and the representative, which makes them both detached signs of tradition and objects of ethnography (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Citation1991). Where Western national museums’ reproduced copies of prehistoric artifacts are found as souvenirs and kitsch in their shops, the Sámi handicrafts that are similarly sold in our two selected museums therefore have a different, more amorphous charge. On one level, the craftsmanship on the shop’s shelves is ‘only’ newly made souvenirs, but from a parallel point of view, they are also in themselves materialized history and cultural heritage. The visiting tourist, who initially spends time in the museums’ exhibition sections, is socialized to realize the latter intangible cultural heritage-charge more deeply (see Kim et al., Citation2019).

As long as these logics between time horizons and cultures can be kept separate, no acute anomalies arise. However, our two museums are also tasked with depicting settler life and contemporary Sámi culture. And with that, two seemingly incompatible modes are forced into conflict (). The Sámi are also late modern citizens, living in and after Western materiality and mentality. This is why a distortion arises that is difficult to handle and is likely as mentally challenging to the most traveled tourist as to the professional exhibition curator.

Table 1. Musealized connotations of Sámi and Swedish culture.

Touristic dimensions

Today, both museums are important nodes in their small local communities, and both play important though somewhat diverging roles in local tourism. A joint characteristic is their positive take on tourism, however, seeing it as an asset that needs to be managed carefully. Both museums cooperate with the regional tourism association, the Swedish Lapland Visitors Board, which promotes not least the Sámi dimension of the region as a major attraction. Museums as institutions have high levels of trustfulness among visitors; they are usually regarded as fairly objective mediators of historical interpretation and representation. This therefore works to strengthen their credibility in relation to tourists seeking existential authenticity, as studies have shown that such perceived quality increases in relation to alleged objectivity (Domínguez-Quintero et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2019)

Ájtte is a popular hangout for the local youth and has a close collaboration with Sámij åhpadusguovdásj, the Sámi Education Center, offering courses in reindeer herding, Doudji (Sámi crafts), and the Sámi language. The museum has thus become an important node for Sámi craftsmen, empowering the Sámi population even beyond the local community. The recently added exhibition of Sámi crafts has further contributed to increasing its touristic attractiveness (). The museum is now the most visited place in Jokkmokk municipality, with more than 30,000 visitors annually, many of them from central Europe but with a majority from Sweden. Particularly during the annual winter market, the museum becomes an important node and stakeholder in the local tourism system, providing information on Sámi culture to a global crowd of visitors (Pettersson, Citation2003). Ájtte embraces its touristic potential. Indeed, the museum has offered to allow the municipality to open the local tourist information center on the museum’s premises. While this has not happened yet, the museum already functions as a stop for tourists, and its staff advise them about other Sámi attractions and the few Sámi companies offering further interpretations of their culture. Regarding the museum’s shop, locally produced quality products and books are offered as souvenirs, and it is reported that tourists interrogate the staff about the Sámi authenticity of the products on offer. A museum restaurant, offering local food including reindeer, is a popular gathering place for locals and tourists alike.

Even Silvermuseet plays an important role in the local community. In addition to numerous programs offered to schools, it also offers a program to the public including lectures by INSARC, the Institute for Arctic Landscape Research, the research section of the museum. However, the dominant group of tourists in the municipality, i.e. central European staff of the car testing industry utilizing the cold climate and staying during the winter, does not play a core role for the museum. Even Norwegian tourists passing through on their way to the coast of the Bothnian Sea are seldom among visitors. Instead, individual travelers form the museum’s main visitor group. These visitors are often part of the grey fleet, and are well traveled. As the museum is strategically located and also houses the local tourist information office, it is the self-evident point of entry for visitors to Arjeplog/Árjapluovve. Around 40,000 visitors are counted annually. The municipality’s limited overall touristic supply implies that the museum has little to recommend when it comes to cultural activities and particularly Sámi attractions, and for local acceptance of the museum it is also important that it not channel tourists to sensitive areas for reindeer herding. The museum’s shop offers an attractive supply of books and local produce, but does not focus on traditional souvenirs. Seeing its role as complementary to other local shops, the museum does not offer a café, to avoid competition with local enterprises.

Conclusions

The museums discussed in this article are important elements of the tourism system in northern Sweden, offering food for thought for specialist and generalist tourists alike. They obviously balance between the museal assignment of collecting and their touristic assignment to entertain and contribute to regional development, and they are highly aware of these dual roles. The study has revealed that a potential conflict between the different assignments is not a particular challenge for the museums’ management; tourism is embraced as an opportunity to disseminate the museums’ activities to a wider and international audience. This is in line with previous research on the intersection of tourism and indigenous peoples (Ruhanen & Whitford, Citation2019; Walker & Moscardo, Citation2016).

This positive inclination toward tourism, however, does not imply a total adaptation to the needs of tourists. Certainly, interpretation is offered in multiple languages and exhibitions are designed with a touristic target group in mind. Still, the exhibitions convey the complex realities of the indigenous past and present. Even in the museum shops, typical tourist offers are somewhat absent. Instead, books, food items, and design products, always with high-quality and ecological ambitions, dominate. In one case, a clear touristic supply is disregarded in deference to other business interests in the community. This reflects a modest strategy that is well in line with tourist perceptions of the northern periphery as a wilderness and frontier hitherto largely untouched by mass consumption (cf. Hall & Boyd, Citation2005).

Overall, it can be argued that the museums apply an almost inverted version of the limitation strategies proposed by Zeppel (Citation2006). They provide fixed opening hours at fixed places, and guarantee access to indigenous resources in a regional tourism system characterized by long distances, sparse population structures, and a limited commercial touristic supply. Hence, rather than limiting indigenous tourism supply, they aim to guarantee a basic supply that is of high educational quality. They are thus important anchors for tourism in the region, and particularly individually traveling international tourists attracted by an Arctic imagination of the region seem to embrace the museums to get into contact with an otherwise seemingly non-material and non-visible indigenous heritage. From this perspective, the museums can be seen as a way of decolonizing indigenous tourism, by taking control over the narratives and imagery (Weaver, Citation2010). Further, the authoritative setting of a museum counteracts a commodification of indigenous culture into the sometimes comic, frivolous experiences and products observed in more commercial settings (Kramvig, Citation2017; Müller & Pettersson, Citation2006).

Hence, being predetermined entry points into small communities, indigenous museums can take a core position in indigenous tourism systems, as a readily available touristic supply. They can be combined with commercial offers at the destination; this is particularly true when museum funding schemes do not directly depend on tourism incomes. Here, museums are enabled to seriously engage with indigenous heritage without considering success merely in terms of visitor numbers or ticket incomes. Thus, tourism does not force museums to compromise with tourism requirements; rather, tourists’ requirements to undertake activities can be seen as an opportunity to fulfill the museums’ ambitions to convey knowledge about the often complicated indigenous history and heritage. While this study addressed this topic from a supply-side perspective, future studies assessing the visitor experience at indigenous museums could indicate how tourists perceive and cope with these institutions and the messages they convey.

Acknowledgment

We would like to highlight the contributions of our informants at the museums, who generously shared with us their knowledge about museums and tourism. Furthermore, we acknowledge that this research was conducted within the FORMAS-funded project ‘Climate Change and the Double Amplification of Arctic Tourism: Challenges and Potential Solutions for Tourism and Sustainable Development in an Arctic Context’ (2018-02228).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Pettersson

Richard Pettersson is a research associate professor and senior lecturer in museology at the Department of Culture and Media Sciences, Umeå University. His research radiates together on the overall subject of Swedish memorial care during the twentieth century, towards the present. This has lately involved themes on cultural heritage management, tourism and entrepreneurship, the role of museums in society and the new arenas of cultural heritage rhetoric.

Dieter K. Müller

Dieter K. Müller is a professor of geography, Umeå University, with a research focus on tourism in northern peripheries. His interests include second homes, tourism labor markets and indigenous tourism in the European Arctic. Müller is the past chair of the International Geographical Union Commission of Tourism, Leisure and Global Change and an editor of the Springer book series Tourism and Global Change.

Notes

1 All citations have been translated from Swedish by the authors.

References

- Abascal, T. E. (2019). Indigenous tourism in Australia: Understanding the link between cultural heritage and intention to participate using the means-end chain theory. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1549053

- Andresen, A., Evjen, B., & Ryymin, T. (Eds.). (2021). Samenes historie fra 1771 til 2010. Cappelen.

- Babich, B. (Ed.). (2017). Hermeneutic philosophies of social science. de Gruyter.

- Belder , L., & Porsdam, H. (Eds.). (2017). Negotiating cultural rights: Issues at stake, challenges and recommendations. Edward Elgar.

- Bennett, T. (1995). The birth of the museum. History, theory, politics. Routledge.

- Bennett, T. (2004). Pasts beyond memory. Evolution, museums, colonialism. Routledge.

- Bennett, T. (2018). Museums, power, knowledge: Selected essays. Routledge.

- Botterill, D., Owen, R. E., Emanuel, L., Foster, N., Gale, T., Nelson, C., & Selby, M. (2000). Perceptions from the periphery: The experience of Wales. In F. Brown, & D. Hall (Eds.), Tourism in peripheral areas (pp. 7–38). Channel View.

- Butler, R., & Hinch, T. (Eds.). (1996). Tourism and indigenous peoples. International Thompson Business Press.

- Butler, R., & Hinch, T. (Eds.). (2007). Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Bylund, E. (1956). Koloniseringen av Pite lappmark t.o.m. år 1867. Geographica 30, Uppsala.

- Ciesielska, M., Wolanik Boström, K., & Öhlander, M. (2018). Observation methods. In M. Ciesielska, & D. Jemielniak (Eds.), Qualitative methodologies in organization studies: Volume II: Methods and possibilities (pp. 33–52). Palgrave Macmillan.

- de Bernardi, C. (2019). Authenticity as a compromise: A critical discourse analysis of Sámi tourism websites. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527844

- de la Maza, F. (2016). State conceptions of indigenous tourism in Chile. Annals of Tourism Research, 56(1), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.008

- de Lima, I. B., & King, V. T. (2018). Tourism and ethnodevelopment: Inclusion, empowerment and self-determination. Routledge.

- Domínguez-Quintero, A. M., González-Rodríguez, M. R., & Roldán, J. L. (2019). The role of authenticity, experience quality, emotions, and satisfaction in a cultural heritage destination. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5-6), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1554666

- Fraser, R. (2022). A museum in the taiga: Heritage, ethnic tourism and museum-building amongst the Orochen in northeast China. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(5), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2022.2083513

- Gray, C. (2015). The politics of museums. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hall, C. M. (2005). Tourism: Rethinking the social science of mobility. Pearson.

- Hall, C. M. (2007a). North-south perspectives on tourism, regional development and peripheral areas. In D. K. Müller, & B. Jansson (Eds.), Tourism in peripheries: Perspectives from the Far North and South (pp. 19–37). Cabi.

- Hall, C. M. (2007b). Politics, power and indigenous tourism. In R. Butler, & T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples (pp. 305–318). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hall, C. M., & Boyd, S. W. (Eds.). (2005). Nature-based tourism in peripheral areas: Development or disaster? Channel View.

- Heldt Cassel, S., & Maureira, T. M. (2017). Performing identity and culture in Indigenous tourism: A study of Indigenous communities in Québec, Canada. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 15(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2015.1125910

- Hinch, T., & Butler, R. (2007). Introduction: Revisiting common ground. In R. Butler, & T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications (pp. 1–12). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hinch, T. D., & Delamere, T. A. (1993). Native festivals as tourism attractions: A community challenge. Journal of Applied Recreation Research, 18(2), 131–142.

- Hodder, I. (1994). The interpretation of documents and material culture. In J. Goodwin (Ed.), Sage biographical research (pp. 171–188). Sage.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. (1992). Museums and the shaping of knowledge. Routledge.

- Horwood, M. (2018). Sharing authority in the museum: Distributed objects, reassembled relationships. Routledge.

- Jenkins, J. M., & Hall, C. M. (1998). The restructuring of rural economies: Rural tourism and recreation as a government response. In R. Butler, C. M. Hall, & J. Jenkins (Eds.), Tourism and recreation in rural areas (pp. 43–68). Wiley.

- Johansson, C., & Bevelander, P. (Eds.). (2017). Museums in a time of migration: Rethinking museums’ roles, representations, collections and collaborations. Nordic Academic Press.

- Karp, I., & Lavine, S. D. (Eds.). (1991). Exhibiting cultures. The poetics and politics of museum display. Smithsonian.

- Kelly-Holmes, H., & Pietikäinen, S. (2016). Language: A challenging resource in a museum of Sámi culture. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1058186

- Keskitalo, E. C. H. (ed.). (2019). The Politics of Arctic Resources: Change and Continuity in the “Old North” of Northern Europe. Routledge.

- Kim, S., Whitford, M., & Arcodia, C. (2019). Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: The intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5-6), 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1991). Objects of ethnography. In I. Karp, & S. D. Davis (Eds.), Exhibiting cultures: The poetics and politics of museum display (pp. 386–443). Smithsonian.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1998). Destination culture: Tourism, museums and heritage. University of California Press.

- Knell, S., Aronsson, P., & Amundsen, A. B., (Eds.). (2011). National museums: New studies from around the world. Routledge.

- Kramvig, B. (2017). Orientalism or cultural encounters? Tourism Assemblages in cultures, capital and identities. In A. Viken, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism and indigeneity in the Arctic (pp. 50–68). Channel View.

- Kuoljok, S. (2008). Att göra ett samiskt kulturarv synligt. Fataburen 2008, 253–267.

- Lantto, P., & Mörkenstam, U. (2008). Från “lapprivilegier” till rättigheter som urfolk: Svensk samepolitik och samernas politiska mobilisering. Fataburen 2008, 59–84.

- Leu, T. C. (2019). Tourism as a livelihood diversification strategy among Sámi indigenous people in northern Sweden. Acta Borealia, 36(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003831.2019.1603009

- Leu, T. C., Eriksson, M., & Müller, D. K. (2018). More than just a job: Exploring the meanings of tourism work among Indigenous Sámi tourist entrepreneurs. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(8), 1468–1482. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1466894

- Leu, T. C., & Müller, D. K. (2016). Maintaining inherited occupations in changing times: The role of tourism among reindeer herders in northern Sweden. Polar Geography, 39(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1148794

- Lilja, A. (1996). Föreställningen om den ideala uppteckningen: En studie av idé och praktik vid traditionssamlande arkiv. Uppsala: Dialekt- och folkminnesarkivet.

- Ljungdahl, E. (2012). Kulturmiljöarbete i praktiken. In P. Sköld, & K. Stoor (Eds.), Långa perspektiv: Samisk forskning & traditionell forskning (pp. 146–157).

- Lundmark, L. (2008). Stulet land: Svensk makt på samisk mark. Ordfront.

- Macdonald, S.2011). A companion to museum studies. Wiley-Blackwell.

- MacLeod, S., Hourston Hanks, L., & Hale, J. (Eds.). (2012). Museum making: Narratives, architectures, exhibitions. Routledge.

- Magnani, M., Guttorm, A., & Magnani, N. (2018). Three-dimensional, community-based heritage management of indigenous museum collections: Archaeological ethnography, revitalization and repatriation at the Sámi Museum Siida. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 31(3), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2017.12.001.

- Müller, D. K. (2011). Tourism development in Europe’s “last wilderness”: An assessment of nature-based tourism in Swedish Lapland. In A. A. Grenier, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Polar tourism: A tool for regional development (pp. 129–153). Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Müller, D. K. (2015). Issues in Arctic tourism. In B. Evengård, J. Nymand Larsen, & Ø Paasche (Eds.), The New Arctic (pp. 147–158). Springer.

- Müller, D. K., & Brouder, P. (2014). Dynamic development or destined to decline? The case of Arctic tourism businesses and local labor markets in Jokkmokk, Sweden. In A. Viken, & B. Granås (Eds.), Destination development in tourism: Turns and tactics (pp. 227–244). Ashgate.

- Müller, D. K., & Hoppstadius, F. (2017). Sami tourism at the crossroads: Globalization as a challenge for business, environment and culture in Swedish Sápmi. In A. Viken, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism and indigeneity in the Arctic (pp. 71–86). Channel View.

- Müller, D. K., & Huuva, S. K. (2009). Limits to Sami tourism development: The case of Jokkmokk, Sweden. Journal of Ecotourism, 8(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040802696015

- Müller , D. K., & Jansson, B. (2007). The difficult business of making pleasure peripheries prosperous: Perspectives on space, place and environment. In D. K. Müller, & B. Jansson (Eds.), Tourism in peripheries: Perspectives from the Far north and south (pp. 3–18). CABI.

- Müller, D. K., & Pettersson, R. (2001). Access to Sami tourism in northern Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250127793

- Müller, D. K., & Pettersson, R. (2006). Sámi heritage at the winter festival in Jokkmokk, Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600560489

- Niskala, M., & Ridanpää, J. (2016). Ethnic representations and social exclusion: Sáminess in Finnish Lapland tourism promotion. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(4), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1108862

- OECD. (2019). Linking the indigenous Sami people with regional development in Sweden. Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/19909284.

- Olsen, K., Abildgaard, M. S., Brattland, C., Chimirri, D., De Bernardi, C., Edmonds, J. …, & Viken, A., (2019). Looking at Arctic tourism through the lens of cultural sensitivity: ARCTISEN – A transnational baseline report. Multidimensional Tourism Institute.

- Onciul, B. (2015). Museums, heritage and indigenous voice: Decolonising engagement. Routledge.

- Pettersson, R. (2002). Sami tourism in northern Sweden: Measuring tourists’ opinions using stated preference methodology. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840200300407

- Pettersson, R. (2003). Indigenous cultural events: The development of a Sami winter festival in Northern Sweden. Tourism, 3(4), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840200300407

- Psarra, S. (2009). Architecture and narrative: The formation of space and cultural meaning. Routledge.

- Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2019). Cultural heritage and Indigenous tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1581788

- Ryan, C., & Aicken, M. (Eds.). (2005). Indigenous tourism: The commodification and management of culture. Elsevier.

- Ryker-Crawford, J. (2017). Towards an indigenous museology: Native American and First Nations representation and voice in North American museums. University of Washington.

- Sametinget. (2022). Samer.se – Allt om Sveriges ursprungsfolk och deras land Sápmi, Sábme, Sábmie, Saepmie. Östersund: Samiskt informationscentrum. Available at http://www.samer.se.

- Shapin, S. (2012). The sciences of subjectivity. Social Studies of Science, 42(2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312711435375

- Smith, V. L. (1996). Indigenous Tourism–the 4 H’s. In R. Butler, & T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples (pp. 283–307). International Thompson Business Press.

- SOU. (2009). Kraftsamling! - Museisamverkan ger resultat 2009:15. Fritze Stockholm.

- Spangen, M. (2015). Without a trace? The Sámi in the Swedish history museum. Nordisk Museologi, 2015(2), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3045

- Stjernström, O., Pashkevich, A., & Avango, D. (2020). Contrasting views on co-management of indigenous natural and cultural heritage – Case of Laponia World Heritage site, Sweden. Polar Record, 56, E4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247420000121

- Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2003). Heritage tourism. Prentice Hall.

- Varnajot, A. (2020). Rethinking Arctic tourism: Tourists’ practices and perceptions of the Arctic in Rovaniemi. Geographical Society of Northern Finland.

- Viken, A., & Müller, D. K. (eds.). (2017). Tourism and Indigeneity in the Arctic. Channel View.

- Vladimirova, V. (2017). Sport and folklore festivals of the North as Sites of indigenous cultural revitalization in Russia. In A. Viken, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism and indigeneity in the Arctic (pp. 182–204). Channel View.

- Walker, K., & Moscardo, G. (2016). Moving beyond sense of place to care of place: The role of Indigenous values and interpretation in promoting transformative change in tourists’ place images and personal values. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8-9), 1243–1261. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177064

- Weaver, D. (2010). Indigenous tourism stages and their implications for sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903072001

- Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2016). Indigenous tourism research, past and present: Where to from here? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8-9), 1080–1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1189925

- Whitford, M. M., & Ruhanen, L. M. (2010). Australian indigenous tourism policy: Practical and sustainable policies? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003602325

- Zeppel, H. (2006). Indigenous ecotourism: Sustainable development and management. Cabi.

- Zhang, J., & Müller, D. (2018). Tourism and the Sámi in transition: A discourse analysis of Swedish newspapers, 1982–2015. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 163–182. doi:10.1080/15022250.2017.1329663