ABSTRACT

This article critically reflects on the implementation of participatory video (PV) to explore the perspectives of 14 refugee participants regarding their place-making strategies in the Netherlands. The insights here derive from the experience of co-designing and implementing the Digital Place-makers program: a filmmaking course that relies on basic editing training and story-telling. PV has been strongly criticized for its attendance to researchers’ output requirements during the production process. We address this issue by focusing on our role as facilitators in acquiring editing skills and capacities that allow participants to produce their films as autonomously as possible. In doing so, we found that engaging in editing techniques during PV had multiple benefits for the refugees, such as enabling a pathway for regaining confidence and highlighting social injustice in their communities. We also argue that knowledge co-production in refugee research must question labels of vulnerability that prevent participants from enjoying authorship of their productions.

Introduction

As digital participatory methods continue to expand and technologies become increasingly accessible, so does their potential to have a profound impact on research. From a general perspective, participatory methods have been celebrated for facilitating the production of knowledge in a collaborative way as these offer opportunities to create spaces for ‘dialogical teaching and learning’ emphasizing knowledge exchange rather than knowledge extraction (Marzi Citation2021, 5). In migration research, the approach of knowledge exchange and co-production is increasingly at the center of ethical debates, especially when involving forced migrant communities and refugees. Issues of knowledge extraction have been flagged as part of ethical considerations of power inequities in the process of collecting and disseminating data without considering migrants’ autonomy and expertise in their own experiences, livelihood, and trajectories (Bloemraad and Menjívar Citation2021). In response to these concerns, participatory methods in refugee-focused research recognize that participants hold unique knowledge and should adopt a role beyond being mere research subjects (Robertson and Simonsen Citation2013). However, it is not sufficient to involve vulnerable migrant populations in decisions of data analysis or dissemination; participatory methods call for researchers to ground their study in a commitment to understand the participants’ context vis-à-vis the research design and implementation processes.

Now, with increasingly accessible and widespread digital technologies – but also increasingly necessary, as evidenced in the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic – participatory methods in migration research encounter new opportunities, but also face new challenges. Digital technologies have been studied in conjunction with forced migration in both transnational (Fiedler Citation2019; Gillespie, Osseiran, and Cheesman Citation2018) and localized practices (Sarria Sanz and Alencar Citation2020; Alencar and Tsagkroni Citation2019), with concepts such as ‘mediatized migrants’, ‘digital diasporas’ or ‘connected migrants’ being used more and more frequently (Leurs and Smets Citation2018). However, the use of digital technologies for knowledge co-production with vulnerable populations is still at a very early stage (Marzi Citation2021). Consequently, our understanding of the benefits and challenges this might bring is limited and the ethics in practice for navigating them still require much work (Grabska Citation2022; Ratnam and Drozdzewski Citation2021). For example, power inequities between researchers and participants, the negotiation of the goals of the project, and issues associated with participant’s trust, agency, or ownership, are challenges that we are only beginning to understand considering digital participatory methodologies. In addition, digital participatory methods can play at odds with issues of connectivity, access, and media literacy skills, which can represent important obstacles among forced migrant populations (Alencar Citation2020).

Joining this growing interest in leveraging participatory methods in migration research, this article reflects on the process of using participatory video to explore the perspectives of 14 participants with refugee background regarding their place-making process in the Netherlands. This methodology is embedded in a larger research project called Translocal Lives, a multi-stakeholder study that aims to understand the various ways in which refugee migrants creatively and/or effectively use technologies, and how this affects their social participation in the host society. The project was funded by the Erasmus Trustfunds Foundation and carried out at Erasmus University Rotterdam from January 2021 to March 2022. Within this larger project, several stages were developed, including in-depth interviews, media-mapping, and a hybrid (online/in-presence) program called Digital Place-makers for experimenting with amateur filmmaking and story-telling. The insights in this paper derive from the experience of designing, implementing and reflecting on the Digital Place-makers program that took place during 7 weeks between September and October 2021 and that relied heavily on digital participatory video to co-produce 11 short films in collaboration with refugee participants. The relevance of reflecting on our experience with participatory video is twofold: on the one hand, we recognize the relevance of continuing to shed light on the voices and perspectives of refugees, who have not only been systematically removed from media-making (Bruinenberg et al. Citation2021) but who increasingly face a problem of research fatigue and knowledge extraction (Bloemraad and Menjívar Citation2021; Vera Espinoza Citation2020). On the other hand, we aim to provide critical methodological insights into participatory video with refugees, as we believe that this method offers much-needed opportunities to engage with social impact-oriented research in the field of forced migration studies.

In what follows, we outline the research context and explain how the Digital Place-makers program was co-design and implemented. Next, we reflect on the use of participatory video to co-produce knowledge with refugees while highlighting its potential to empower their communities. Last, we turn to ethical considerations regarding ownership, confidentiality and vulnerability that were central to our experience.

The use of participatory video in refugee-focused research

Participatory video is a collaborative technique that aims to involve a community or group in the co-creation of their own film(s) (Lunch and Lunch Citation2006). Central to Participatory Video is the challenging of ‘traditional filmmaking practices that narrate stories about rather than create stories with protagonists’ (Lenette Citation2019, 202). Notably, Participatory Video stems from Participatory Action Research and has been increasingly adapted by researchers collaborating with vulnerable communities, especially with the advent of digital technologies: smartphone cameras, freely available editing software, and social media platforms for dissemination, have unlocked the potential of amateur filmmaking to various communities in limiting contexts (Lenette Citation2019). Lenette (Citation2019) suggests a growing interest in the field of forced migration in Participatory Video methodologies, although these are still under-explored. More common is the implementation of digital story-telling or photovoice (see, e.g., Fish and Syed Citation2021; Liegghio and Caragata Citation2021; Humpage et al. Citation2019), two closely related methods. Such interest in Participatory Video, however, has been fueled by the rise of a number of documentaries, short movies, and films directed and produced by amateur filmmakers with a refugee background that has drawn significant attention during different well-known film festivals, for example, ‘Nauru Refugee Voices’ or ‘Chauka, Please Tell Us The Time’.

Many Participatory Video studies in refugee-related research argue that the method has an enormous potential to empower individuals by equipping them with skills to ‘show and tell’ their needs and hopes situated in their local context (Lunch and Lunch Citation2006, 14). For example, the project Cross-Marked: Sudanese Australian Young Women Talk Education captures the educational experiences of Sudanese women as they cope with motherhood. The result was the co-production of seven short documentary films that seek to counter the imposed narratives that oversimplify experiences of refugee women in their trajectories of belonging and becoming (Harris Citation2010). Similarly, the Home Lands project led by Gifford and Wilding (Citation2013) discusses the relevance of participatory filmmaking in bringing to the fore the tensions of intersectional identities that refugees negotiate. In this case, 34 Karen Burmese refugees collaborated to produce different digital outputs during the project. Refugee-related studies do not only highlight the relevance of Participatory Video to advance counter-narratives or voice refugee communities’ concerns about specific topics; it has also been discussed as a method with transformative potential for the participants (Lenette Citation2019). An example is the Visualizing the Voices of Migrant Women Workers project led by Lin et al. (Citation2019), where the research team concludes that the creative space enabled by the method was beneficial to catalyze and reflect on emotions related to discomfort, gratitude, and trepidation triggered during the workshops. In fact, story-telling – a key component of filmmaking – has been implemented consistently in (mental) health research because the ‘process encourages protagonists to work through their experiences and reflect on and deepen their understandings of what really matters in their lives’ (Lenette Citation2019, 124). Vasudevan and Riina-Ferrie (Citation2019), for instance, applied story-telling as a research tool to examine issues of identity, civic participation and creative practices among youth participants by engaging them in reflections about their experiences of a participatory video project.

Despite the efforts of implementing Participatory Video in the field of forced migration as illustrated above, we noted that a less explored part of the methodology is the editing process. In general, Participatory Video studies adopt a No Editing Required (NER) approach in which participants can create a video but do not engage in editing training or need a digital editing suite. The NER approach has been argued to respond to different issues associated with Participatory Video: editing can be technically challenging and time-consuming for participants (Mak Citation2012) and, in addition, can yield power imbalances and impose top-down views on the participants’ films (Blomfield and Lenette Citation2018; Grabska Citation2022; Marzi Citation2021). We argue, however, that a NER format can sometimes mask an approach to vulnerability rooted in colonizing research practices and labeling discourses involving refugee communities. Instead, we propose that more efforts should be made to engage with (semi)participatory editing (Lockowandt Citation2013) as this not only brings important benefits to participants, but also, can become a key starting point to reflect on the tensions that the editing process brings about. As Parr (Citation2007, 126) puts it, collaborative editing ‘throws up a difficult range of issues about endurance, representation, ethics and inclusion’. We will explore this issue in depth later in the article by providing empirical examples drawn from our own experience in engaging with editing training and production.

Research context and the co-design of the Digital Place-makers program

In migration studies, a significant effort to emphasize issues of place-making, resettlement, and belonging has gained important traction in recent years (Alencar Citation2020). Migrant and refugee populations are increasingly studied through the lenses of translocality – a conceptual approach that highlights the agency of refugees in their own settlement processes (Jean Citation2015). This major shift away from an essentialist perspective on places (Brun Citation2001) has also been accompanied by the use of communication and information technologies. Increasingly, we observe place-making processes where digital technologies play an important part, for example, in the creation of local support networks, the search for relevant information on work, education or health, or the sharing of learned experiences with the refugee community (Sarria Sanz and Alencar Citation2020). Digital technologies allow migrants to establish relationships with their local environment without losing connection with their places of origin and with the global context.

In the Translocal Lives Research Project, we not only aimed to identify the various ways in which refugee migrants use technologies to create a sense of place, but we also delved into how digital technologies provide new opportunities to access refugee ‘in situ and in real-time’ experiences (Marzi Citation2021, 3). Particularly, we explored the potential of participatory video to tap into issues of belonging, identities, aspirations, sociabilities, and well-being. To this end, we co-designed the Digital Place-makers program, a 7-week hybrid (online/in-person) filmmaking course that involved 14 newcomers with refugee background, a media artist, and the researchers, who had long experience in developing educational initiatives aimed at social inclusion of refugee communities and marginalized groups. The participants had diverse socio-economic backgrounds and had been living in the Netherlands between one and seven years. There was also significant diversity regarding their countries of origin, including Syria, Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, and Eritrea. Among the participants, 7 were women and 7 were men and their ages varied from 24 to 47 years old. All the participants were recruited through snowball sampling and established connections with refugee-led associations and social media platforms (e.g., LinkedIn and Instagram).

The goal of the program, shaped together with the participants, was the production of individual amateur short films where each newcomer explored their perspective on place-making as autonomously as possible. To achieve this, the program included training in basic video and editing tools as well as in story-telling and creative writing. Both smartphones and laptops were used. The design phase of the Digital Place-makers program was assisted by two key informants of the refugee community, Adel AlBaghdadi and Jaber Mawazini. Adel is the founder of WE Organization, an initiative that addresses issues of xenophobia and social inclusion among refugees in the Netherlands. Adel was key to understanding participants’ motivations for enrolling in a program like the Digital Place-makers and helped us emphasize the pedagogical component that later would be central to address our concerns regarding research fatigue among the refugee community (Bloemraad and Menjívar Citation2021; Vera Espinoza Citation2020). On the other hand, Jaber joined us as a researcher and cultural advisor and assisted us in the recruitment of participants and in building trust among the group. Having experienced forced migration himself, Jaber is actively involved in refugee-related issues in the Netherlands, particularly, regarding the Syrian community. He provided important insights into ethical considerations during the implementation of the program. For instance, his perspective was crucial in assessing better our approach to the vulnerability of the participants (a topic that will be discussed later). In addition, Jaber accompanied us in several interviews and provided crucial support in both linguistic and cultural translation. Both Adel and Jaber’s involvement helped us engage in a better co-design process and consider deeply our participants’ needs and constrains, core principles of participatory research (Fish and Syed Citation2021).

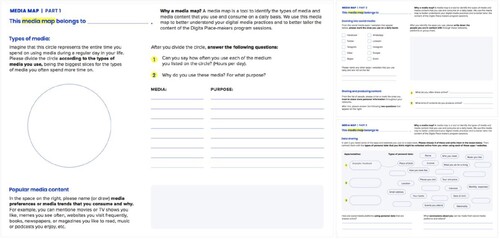

In line with our participatory approach, media maps were developed with the participants prior to the start of the program. The media maps were part of the in-depth interviews conducted between May and July of 2021 with the purpose of identifying the participants’ media preferences and consumption habits, sharing practices, privacy concerns, data management, among others. More importantly, these media maps helped us evaluate the feasibility of the program in terms of access to devices (smartphones and laptops), but also it helped us grasp the different media literacy skills of the group.

Consequently, we developed important insights into how comfortable the participants were in using their smartphones to engage with filmmaking and story-telling workshops. In fact, the diversity among the participants in terms of socio-economic background, age, country of origin, time living in the Netherlands, and strategies for place-making, signaled important differences to consider regarding how they would feel while learning new digital skills during the program and engaging in creative exercises. For example, Ibrahim,Footnote1 a 26-year-old Syrian participant, showed remarkable knowledge of several digital media skills but struggled with the creative aspect of the activities. As a result, he decided to get involved in helping others to realize their film projects by providing technical assistance but not in producing his own film. In contrast, Farah, a 38-year-old Iranian woman, did not feel confident in the technical aspect of video editing at the beginning. However, her determination to learn new skills together with the assistance of the media artist, helped her to produce two short films shot and edited by herself entirely. In her own words:

The first sessions I didn’t know what would happen, but step by step I learned something so I became so happy because I can make some movies now. Before I couldn’t. And I thought this is a way to show your feelings, your thoughts, what you do. And when you can make it, you can share it with other people and that gives you energy. (Farah, 38, Iran)

After several iterations in the design of the program, Digital Place-makers began on 4 September of 2021 and spanned during the following 7 weeks. Every week, on Saturdays, we would meet with the participants in-person on the Anonymous University campus for a three-hour workshop session. We were fortunate that by this time, cases of COVID-19 had decreased sufficiently in the Netherlands, and restrictions had been eased for a period of approximately 3 months. Therefore, we were able to conduct the program in a hybrid format, adhering to the biosecurity measures implemented on campus and recommended for small-sized groups such as ours during in-person meetings. An important note in this respect is that we noticed that Saturdays became an extremely valuable ludic space for the participants, many of whom had come to the Netherlands during the pandemic or just prior to the intense first lockdown. As a result, participants were not only eager for physical interactions with others but were also keen to be stimulated through creative learning. Aida, a 35-years-graphic designer from Iran said: ‘We had a very good relationship with each other, I was very comfortable, I had no stress. I really played during this course and I enjoyed that’. Other studies using participatory methods during the COVID-19 pandemic have accounted for similar experiences. For instance, researching strategies of resilience among women in poor neighborhoods in Medellín, Marzi (Citation2021, 11) explains how the routine meetings even though online, gave the participants a ‘sense of normality’ and helped them create a community to share experiences of injustice and inequality. In a similar way, Liegghio and Caragata (Citation2021, 153) highlight how their remote research using photovoice among low-income youth in Canada became a way for ‘interrupting the negative effects of the pandemic in “real time”’. Like many other research studies designed before the pandemic but implemented in a context of great uncertainty after COVID-19 hit (see Hall, Gaved, and Sargent Citation2021), we had to constantly adapt our work plan to the fluctuating circumstances and government restrictions ().

Figure 1. Media map developed during the online individual interviews.

Participatory video to co-produce knowledge with refugee migrants

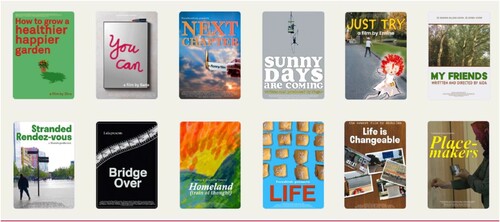

Central to participatory video is the meaningful and active participation by those most affected by an issue. Adopting this approach helped us understand filmmaking and story-telling as tools to empower individuals in sharing their accounts on place-making. Rather than specific guidelines, we focused on providing a broad outline for the creation and curation of content. This allowed participants to feel in charge of their voice and to make autonomous decisions about the pieces most relevant to them in relation to their individual and collective place-making strategies. As Fish and Syed (Citation2021, 273) argue, ‘marginalized and underserved communities are not monolithic or one-dimensional, but rather, represent a diverse range of experiences’. Under this perspective, we focused on delivering the conceptual guidance and technical tools recognizing the learning pace and motivations of each participant. We observed that the Digital Place-makers program became relevant to each of them as long as they were able to focus their efforts on pursuing personal and/or professional goals associated with their aspirations beyond their condition as refugees. Enabling the space to explore their individual motivations and answer the question of ‘why do I want to learn how to create a film?’, was a key starting point of our program and utterly relevant in the role and attitude that participants adopted during the workshops. To respond to the variety of motivations and needs, we implemented two main strategies. First, we offered one-to-one support sessions between Saturdays (when the group sessions took place), to follow participants’ progress more closely and to focus on the challenges they identified in moving forward with their films, both in a technical and conceptual level, but also at an emotional one. In turn, this allowed us to adopt the second strategy. While learning about their individual struggles and achievements, it became necessary to implement a methodology in which each week, the team (media artist, cultural advisor, and us, researchers) would review the contents of the program and tailor the sessions on a weekly basis. In doing so, we aimed to attend in the best way possible to what the participants expected to achieve through the course. The result were 11 amateur short films that reflect their perspectives on belonging, identity, well-being, memory, and resilience, among other topics. Concretely, four themes were preliminarily identified in the films (see ):

Challenges and resilience: in this theme, the films show the stark reality of the refugee journey emphasizing the challenges of leaving home and stepping out into the unknown. The participants, however, also stress their resilience in overcoming the various obstacles they face. The films ‘Sunny Days are Coming’, ‘Next Chapter’, and ‘Life is Changeable’ are examples.

Motivation and opportunities: in this theme, the narrative focuses on the opportunities that participants identify upon arrival in the Netherlands and the relevance of different actors, from family and friends to organizations and institutions, for their place-making process. The main argument is the search for the skills that help them to recognize themselves as valuable individuals in the new society. The films ‘You Can’, ‘Just Try’, ‘Bridge Over’, and ‘How to Grow a Healthier and Happy Garden’ are some examples of this theme.

Memories and connection to home: in this theme, participants explore questions about how to connect with their country of origin, their culture, and their family left behind. In the film ‘Homeland’ Hamoud questions if and how to replace his home, while in the film ‘Life’ Fereshteh shows how a family recipe connects her to memories of her childhood.

Belonging and relation to the city: in this final theme, participants use metaphors to narrate the tensions in the relationship between their identity as refugees and their sense of belonging to the city. In tandem, the films account for some strategies that they develop to better connect with the host society and what questions this process brings about. ‘My Friends’ and ‘Stranded Rendez-vous’ are two examples in this theme.

Figure 2. Posters of the 11 films and the documentary (bottom right) co-created with participants.

Participatory editing

Placing participants at the center of the process allowed us to address critiques of power imbalances between researcher and researched that are discussed within participatory video methods and that particularly focus on the interference of the researchers and filmmakers in the curation of material in the final films (Grabska Citation2022). To safeguard against this pitfall, we not only kept revising and adapting the program on a weekly basis, but we also focused on teaching participants editing skills. In participatory video studies, editing is often the part where participants have less agency and autonomy due to the technical challenges that this skill presents (see Marzi Citation2021). In fact, the majority of studies implementing Participatory Video opt to take a No Editing Required (NER) approach, where participants do not engage themselves in editing. This alternative offers great advantages to the overall project as it brings less complexities at a technical and financial level, and it is also less time-consuming (Mak Citation2012). However, we believe that the lack of engagement in editing training can also risk missing important opportunities for meaning-making and agency-building for the participants (Vasudevan and Riina-Ferrie Citation2019). After all, it is precise during the editing process that crucial decisions are made regarding the composition and framing of a narrative. As Lenette (Citation2019, 216) argues, ‘principles of participatory research should extend to the editing phase so that Knowledge Holders have more control over the way their clips and narratives are constructed in the “final cut”’. Under this perspective, we followed a participatory editing approach in which participants learn the skills necessary to take charge of the editing process under the guidance of a professional (Lockowandt Citation2013). To do so we used ShotCut, a freely available software and in total, we dedicated 9 hours to train participants in editing during group sessions, and 1 extra hour of individual training on average per person under the guidance of the media artist. In what follows, we present three important benefits of participatory editing during the Digital Place-makers program ( and ).

Figure 3. Participants learn and practice editing skills during the workshops.

Figure 4. To understand the logics of editing, participants write their script (visuals and audio) on post-its to play with different types of narratives.

First, we observed that engaging in editing as part of the program provided the opportunity to learn skills and competences that were valuable for the participants beyond the duration of the project. Some participants explained how being trained in editing was relevant to their professional development and aligned with their goals. For Zina, a 25-year-old recently graduated student, the new learnt skills were a relevant addition to her CV while looking for jobs in the marketing and communication field. In another example, Hamoud, a 47-year-old architect from Syria, had already basic training in editing prior to the program but explained how engaging with the process helped him reconnect with skills that he had been struggling to practice since he arrived in the Netherlands one year ago. The fact that participants saw value in learning a new skill that can be used beyond the timeframe of the project was crucial to respond to issues of research fatigue. Research fatigue emphasizes the ‘extractive nature of research’ (Vera Espinoza Citation2020) and signals participants’ discomfort with a lack of retribution or benefits for partaking in a research project (Karooma Citation2019). That is not to say that for all participants receiving editing training was associated with their professional goals. For the majority, retribution was perceived through the impact that learning digital skills and engaging in creative exercises had on their individual well-being. The program enabled a pathway for regaining the confidence that many newcomers have lost due to the traumas associated with the loss of place, identity, or culture (Jean Citation2015). For example, Emine, a 41-year-old woman from Turkey, expressed on many occasions how participating in the workshops made her feel young and capable again. During the follow-up interviews held after the program, she said: ‘It was a really great experience for me, I enjoyed it. I have now a lot of motivations because when I came here I lost all the trust in myself, but this program gave me trust again’. Similarly, Sana, from Pakistan, also expressed the relevance of learning new skills as a strategy for motivation and place-making. This issue was so important to her that it became the central theme of her film titled ‘You can’. In fact, many of the films tap into the theme of motivation and opportunities and describe from first-hand accounts how for refugee newcomers, it is vital to feel valuable to the host society, by for example, finding way to use their skills to contribute in diverse fields. The impact on well-being was not only evident from the perspective of inner self-confidence and reassurance. Throughout the workshops, all the participants decided to focus on the positive aspects of their experiences in the Netherlands, considering their films as instruments that could inspire others in similar situations. The fact that participatory video enables pathways to contribute to the well-being of participants cannot be understated, especially when research among refugee populations often leads to reviving experiences of trauma and distress associated with displacement and loss (Humpage et al. Citation2019; Ratnam and Drozdzewski Citation2021).

Second, we observed how developing autonomy over the narrative through the control of editing choices was crucial for many participants to feel like owners of their films, a core tenet in the co-production of knowledge approach. In turn, this led them to adopt a sense of responsibility to shed light on matters of social injustice in their communities. In this sense, we argue that participatory editing has the potential to empower members of vulnerable communities, like forced migrants and refugees, as agents of change (Fish and Syed Citation2021).

Refugees are a big part of the Netherlands, but they have many problems. I always wanted to show their problems to find a solution, but I couldn’t, I didn’t know a good way to show this. But with this technique, with an efficient film, I managed to show some of these problems. (Negar, 42, Iran)

You never get the chance to share your thing. People are not interested in listening to you because everyone has the same problem (…) but now I got a chance, I want to show them what I have to say.

Third, we found that by understanding the logics of editing, even when the technical skills were not fully mastered, the participants were able to conceive new possibilities for expressing their thoughts through the films. A clear example is the case of Abdullah, a 27-year-old lawyer who fled his country alone in 2017. His film ‘Life is Changeable’ narrates his journey from Turkey to the Netherlands by sequencing photos that he had saved on his phone and adding titles to explain to the audience what each picture was depicting. In one of the final sessions of the program, Abdullah explained that learning how to put voice and music on a video was useful for expressing more clearly how he felt at different times during his journey. An important note here is that we did not pursue high-quality aesthetic production; this was not the goal of the editing training during the program. Participants were able to decide the depth in which each of them engaged with editing tools and how far they explored different options in the editing software.

As we have seen, the multiple advantages of participatory video and editing at individual and collective levels are significantly associated with the impact of the films being shared and watched by a specific audience, including other refugees or members of their communities, decision-makers at a policy level, as well as potential employers in the labor market. The relevance of these audiences for the participants implies that engaging in knowledge co-production cannot be considered separately from a thorough analysis of ethical implications related to the dissemination of their films. In the following section, we turn to the intricacies between ownership and confidentiality in the framework of digital participatory methods for migration research.

Migrant vulnerability: the negotiation of confidentiality versus ownership

The concept of vulnerability is central to understanding ethical practices in studies focused on refugees. Vulnerable populations are those considered to experience a ‘particularly difficult set of life-chances’ (Brown Citation2011, 314). In migration research, refugee communities are considered vulnerable populations and therefore special attention is required to assess risks of emotional and social harm. In addition, refugee-focused research needs to consider the potential experiences of surveillance and persecution that many refugees endure, and the possible implications for their legal status for partaking in research. In this regard, issues of confidentiality, anonymity and privacy are crucial and constitute a central component in ethical considerations. However, as Ratnam and Drozdzewski (Citation2021) argue, researching refugee populations often reveals a mismatch between procedural ethics and its actual fieldwork application. This calls for a more ‘reflexive, situated and transformative research, ethical engagement with research participants and environments, and knowledge production that is participatory, collaborative, and more widely accessible’ (Caretta and Faria Citation2020, 172). We were acutely aware of the power relations underpinning our positionality as privileged migrant women researchers in the Netherlands working with people who experienced forced displacement and had to negotiate their belonging and legal situation in Dutch society in completely different ways. This reinforced our commitment to incorporating the principle of ‘do no harm’ that is guided by the ethics of care and respect (Grabska Citation2022). Following this perspective, a key aspect in the implementation of the Digital Place-makers program was the establishment of ethical guidelines with the participants. To do so, we facilitated a conversation during the welcoming session of the program to decide what was important in order to guarantee a safe and comfortable space throughout the workshops. As a result of the activity, several ethical guidelines were collectively produced in a shared document easily accessed by the group at any time. Concretely, the ethical guidelines considered four main points:

Collection of material and identification: Each participant has the autonomy to decide what content is included in their final film. In line with this, participants can decide if they want to appear in the films or if they will remain completely unidentifiable. This decision pertains to the participant only and will not be questioned by the team or by anyone in the group. In addition, participants have the autonomy to decide whether and how to be involved in the audio-visual documentation of the program.

Cloud-storage: The recorded material will be stored in a private server, only accessible to the participants and the research team. Once the project ends, this material will be deleted, and access accounts will be terminated.

Circulation of content: The content created individually or collectively during the sessions cannot be circulated outside of the program without the consent of its owner/s. This includes the content and conversations held through the WhatsApp group (created with participants to facilitate communication).

Dissemination of the films: Each participant is autonomous in deciding how to disseminate their final film and to which audience. Possibilities for collective dissemination (e.g., screening nights, websites, online exhibitions) were discussed as a group at the end of the program.

We decided to engage in the co-design of ethical agreements stemming from concrete concerns of the group rather than implementing a set of standardized guidelines that oftentimes do not reflect the realities of the research (Ratnam and Drozdzewski Citation2021; Bloemraad and Menjívar Citation2021). By doing so, we were careful to consider the particular concerns of each participant, an essential practice to guard against a label approach to vulnerability (Luna Citation2009) that is prevalent in refugee-focused research (Humpage et al. Citation2019). Under this approach, participants not only end up being stripped of their autonomy, but they are not recognized as experts in their context and the challenges they or their communities face. Thus, the label approach to vulnerability contradicts the core principles of participatory methods and can disempower the individuals that partake in research. On the contrary, as Luna (Citation2009) explains, a layered approach allows one to consider the dynamic character of vulnerability and to understand the specificities of the environmental and personal circumstances of each individual. While recognizing the complexities of the ongoing debate on migrant vulnerability (La Spina Citation2021), the layered approach provides an important framework for reflecting on the intricacies of the relation between confidentiality and ownership that emerged as part of the dissemination of the films.

In refugee-focused research, safeguarding confidentiality can be crucial to protect not only the individual, but also their family or loved ones left behind (Bloemraad and Menjívar Citation2021). During the program, we evidenced that many participants were aware of the implications of being identified through their films and approximately half of the participants chose not to be identified through the audio-visual content. The other participants adopted varying degrees of exposure, ranging from including some biographical information, to describing specific lived experiences, and in few cases showing their faces and those of family members. This range of outcomes underpins the pertinence for a layered approach to a vulnerability that recognizes the particularities of each case and their autonomy in making such decisions, while enabling constant (re)negotiations regarding the identification of participants and their visual projects. Therefore, our role here was limited to ensuring that everyone understood and carefully assessed the implications of identification, rather than determining the ‘correct’ type of content included in their films.

Within participatory video, this discussion is even more necessary due to the methodological approach and outcomes of the program. In this case, authorship implies a concrete source of identification, especially when participants are interested and wish to disseminate their films to different audiences. During informal conversations we had with them, particularly in individual online sessions, many expressed the relevance of sharing their creations with others. On an individual level, being identified as the author addresses considerations of ownership and credit that they see beneficial, particularly those concerned with showcasing media skills for potential jobs, like Hamoud or Zina. For others, authorship is more focused on feeling proud and capable, as in the case of Emine or Ronny. Nevertheless, at a collective level, the group also expressed the relevance of circulating their films beyond academia. For many, the opportunity to put their films out there is related to the possibilities of impacting not only how Dutch society perceives refugees, but how refugee communities perceive themselves. Sana’s words reflect this perspective: ‘You can. That is the main goal of what I want to say. That sometimes you are stuck in a difficult situation where you can’t find the ways to get out, but you have the ability and you can’. While we are aware that confidentiality is crucial in research with migrant populations and refugees, we cannot fail to include them in the conversation, as they constantly challenge research practices and institutional ethical guidelines.

Concluding points

Throughout this article, we have sought to highlight the relevance of participatory video as a creative research method with much to offer to the field of forced migration. Prompted by the growth in the study of the role of digital technologies in the lives of refugees, we have sought to understand how such technologies are not only key to develop place-making strategies (Alencar Citation2020) but are also means for co-producing knowledge. Our reflection on the co-design and implementation of the Digital Place-makers program highlights several important points that have also been stressed in other studies that use participatory video to better understand the migratory trajectories of refugee communities. The most relevant, perhaps, is the impact of this method on the individual well-being of participants who have endured traumatic experiences related to their displacement and loss of identity (Jean Citation2015). As we discussed earlier, well-being is associated with the regained confidence and assertiveness that comes with learning new skills such as story-telling, creative writing, and editing. The latter, however, remains an unexplored phase in most projects implementing participatory video (Marzi Citation2021). We argue that integrating participatory editing can also have an important social impact on communities at the collective level. Therefore, the relevance of the method is not just that we can co-produce more authentic stories that better reflect a community’s perspective; beyond that, it is to provide communication tools to a community that has been systematically sidelined from producing its own discourses, imaginaries and aspirations. As Fish and Syed (Citation2021) recognize, when implemented right, participatory video (and participatory editing) is a powerful tool for equipping agents of social change.

As evidenced throughout the article, we have sought to implement the principles of participatory research at all stages of the project: the co-design of the program with key informants, the establishment of ethical guidelines with participants, the negotiation of workshop objectives and content, and collective decision-making about the dissemination of the resulting films were all key aspects of our participatory approach. Doing so has brought about important reflections on ethical concepts that are central to refugee research. On the one hand, a reflection on the research fatigue that persists in studies implementing more conventional methodologies to research the levies of refugees (Bloemraad and Menjívar Citation2021; Vera Espinoza Citation2020). While we acknowledge that not all studies at the intersection of forced migration and digital technologies can integrate a creative methodology, we do argue that a participatory approach is a crucial starting point for better understanding communities’ motivations for getting involved in any proposed study. And, moreover, we see significant potential in participatory video particularly as a transformative and even fun tool that can be highly motivating for newcomer participants. As Lenette (Citation2019) pointed out after reviewing several studies implementing this method, the therapeutic potential of arts-based methods cannot be ignored, especially considering its implementation in contexts of high uncertainty and limited social contact, such as the current pandemic (Liegghio and Caragata Citation2021; Hall, Gaved, and Sargent Citation2021).

On the other hand, this project also led us to reflect on the mismatch between the ‘ethics on paper’ and the ethics put into practice during a participatory project, which requires a great degree of flexibility and care to respond to the circumstances of each participant. Some inconsistencies were already pointed out by Bloemraad and Menjívar (Citation2021) in an extensive reflection on the requirements of an open-science research approach. In this regard, we argue that the field of forced migration research must commit more consistently to challenge the labels of vulnerability (Luna Citation2009) that prevent refugees from making autonomous decisions about how and to what extent they wish to be identified in a project that aims to produce knowledge collaboratively. In participatory video, such identification is intrinsically linked to the enjoyment of their authorship of the films: how can we negotiate the risks of identification with the benefits of authorship is a question that cannot be answered without involving the participants in the conversation. It would be a mistake to assume their vulnerability without understanding the particularities on a case-by-case basis. We find it striking that this reflection has not been exhaustively explored before, and so we are very keen on pointing it out concretely to better understand how future studies using participatory video can follow-up and contribute greatly to the discussion on such relevant ethical issues.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants for their generosity, time and kindness during the research. We would like to acknowledge the support of Kevin van der Poel (Director of the Erasmus Preparatory Year Programme for Refugees), who believed in our project and supported the organization of the Digital Place-makers workshops and screening night event. The authors also benefited from valuable input during the 9th European Communication Conference (ECREA) in Aarhus, Denmark.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Most participants used their own names for their films; in one case, the participant opted for adopting a pseudonym.

References

- Alencar, A. 2020. “Digital Place-Making Practices and Daily Struggles of Venezuelan (Forced) Migrants in Brazil.” In The SAGE Handbook of Media and Migration, edited by Kevin Smets, Koen Leurs, Myria Georgiou, Saskia Witteborn, and Radhika Gajjala, 503–514. London: Sage.

- Alencar, A., and V. Tsagkroni. 2019. “Prospects of Refugee Integration in the Netherlands: Social Capital, Information Practices and Digital Media.” Media and Communication 7 (2): 184–194. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i2.1955.

- Bloemraad, I., and C. Menjívar. 2022. “Precarious Times, Professional Tensions: The Ethics of Migration Research and the Drive for Scientific Accountability.” International Migration Review 56 (1): 4–32. doi:10.1177/01979183211014455.

- Blomfield, I., and C. Lenette. 2018. “Artistic Representations of Refugees: What is the Role of the Artist?” Journal of Intercultural Studies 39 (3): 322–338. doi:10.1080/07256868.2018.1459517.

- Brown, K. 2011. “‘Vulnerability’: Handle with Care.” Ethics and Social Welfare 5 (3): 313–321. doi:10.1080/17496535.2011.597165.

- Bruinenberg, H., S. Sprenger, E. Omerović, and K. Leurs. 2021. “Practicing Critical Media Literacy Education with/for Young Migrants: Lessons Learned from a Participatory Action Research Project.” International Communication Gazette 83 (1): 26–47. doi:10.1177/1748048519883511.

- Brun, C. 2001. “Reterritorilizing the Relationship Between People and Place in Refugee Studies.” Geograbska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 83 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2001.00087.x.

- Caretta, M., and C. Faria. 2020. “Time and Care in the ‘Lab’ and the Field: Slow Mentoring and Feminist Research in Geography.” Geographical Review 110 (1–2): 172–182. doi:10.1111/gere.12369.

- Fiedler, A. 2019. “The Gap Between Here and There: Communication and Information Processes in the Migration Context of Syrian and Iraqi Refugees on Their Way to Germany.” International Communication Gazette 81 (4): 327–345. doi:10.1177/1748048518775001.

- Fish, J., and M. Syed. 2021. “Digital Storytelling Methodologies: Recommendations for a Participatory Approach to Engaging Underrepresented Communities in Counseling Psychology Research.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 68 (3): 271–285. doi:10.1037/cou0000532.

- Gifford, S. M., and R. Wilding. 2013. “Digital Escapes? ICTs, Settlement and Belonging among Karen Youth in Melbourne, Australia.” Journal of Refugee Studies 26 (4): 558–575. doi:10.1093/jrs/fet020.

- Gillespie, M., S. Osseiran, and M. Cheesman. 2018. “Syrian Refugees and the Digital Passage to Europe: Smartphone Infrastructures and Affordances.” Social Media + Society 4: 1. doi:10.1177/2056305118764440.

- Grabska, K. 2022. “In Whose Voice? And for Whom? Collaborative Filming and Narratives of Forced Migration.” In Documenting Displacement. Questioning Methodological Boundaries in Forced Migration Research, edited by Katarzina Grabska and Christina Clark-Kazak, 201–223. Québec: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Hall, J., M. Gaved, and J. Sargent. 2021. “Participatory Research Approaches in Times of Covid-19: A Narrative Literature Review.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20. doi:10.1177/16094069211010087.

- Harris, A. 2010. “Race and Refugeity: Ethnocinema as Radical Pedagogy.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (9): 768–777. doi:10.1177/1077800410374445.

- Humpage, L., F. Fozdar, J. Marlowe, and L. Hartley. 2019. “Photovoice and Refugee Research: The Case for a ‘Layers’ Versus ‘Labels’ Approach to Vulnerability.” Research Ethics 15 (3-4): 1–16. doi:10.1177/1747016119864353.

- Jean, M. 2015. “The Role of Farming in Place-Making Processes of Resettled Refugees.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 34 (3): 46–69. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdv007.

- Karooma, C. 2019. “Research Fatigue among Rwandan Refugees in Uganda.” Forced Migration Review 61: 18–19. https://www.proquest.com/openview/c663a48a99e46dfb32d1579035c00ce6/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=55113

- La Spina, E. 2021. “Migrant Vulnerability or Asylum Seeker/Refugee Vulnerability? More Than Complex Categories.” Oñati Socio-Legal Series 11 (6(S): S82–S115. doi:10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1225.

- Lenette, C. 2019. Arts-based Methods in Refugee Research. Singapore: Springer.

- Lenette, C., L. Cox, and M. Brough. 2015. “Digital Storytelling as a Social Work Tool: Learning from Ethnographic Research with Women from Refugee Backgrounds.” The British Journal of Social Work 45 (3): 988–1005. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct184.

- Leurs, K., and K. Smets. 2018. “Five Questions for Digital Migration Studies: Learning from Digital Connectivity and Forced Migration In(to) Europe.” Social Media + Society 4 (1). doi:10.1177/2056305118764425.

- Liegghio, M., and L. Caragata. 2021. “COVID-19 and Youth Living in Poverty: The Ethical Considerations of Moving from In-Person Interviews to a Photovoice Using Remote Methods.” Affilia 36 (2): 149–155. doi:10.1177/0886109920939051.

- Lin, V. W., J. Ham, G. Gu, M. Sunuwar, C. Luo, and L. Gil-Besada. 2019. “Reflections Through the Lens: Participatory Video with Migrant Domestic Workers, Asylum Seekers and Ethnic Minorities.” Emotion, Space and Society 33: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2019.100622.

- Lockowandt, M. 2013. “Inclusion Through Art: An Organizational Guideline to Using the Participatory Arts with Young Refugees and Asylum Seekers.” Accessed February 10, 2022. https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2013-Inclusion_Through_Art_-1.pdf.

- Luna, F. 2009. “Elucidating the Concept of Vulnerability: Layers not Labels.” International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 2 (1): 121–139. doi:10.3138/ijfab.2.1.121.

- Lunch, N., and C. Lunch. 2006. Insights into Participatory Video: A Handbook for the Field. Oxford, UK: InsightShare.

- Mak, M. 2012. “Visual Postproduction in Participatory Video-Making Processes.” In Handbook of Participatory Video, edited by E.-J. Milne, Claudia Mitchel, and Naydene de Lange, 194–207. New York: Altamira Press.

- Marzi, S. 2021. “Participatory Video from a Distance: Co-Producing Knowledge During the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Smartphones.” Qualitative Research. doi:10.1177/14687941211038171.

- Parr, H. 2007. “Collaborative Film-Making as Process, Method and Text in Mental Health Research.” Cultural Geographies 14 (1): 114–138. doi:10.1177/1474474007072822.

- Ratnam, C., and D. Drozdzewski. 2021. “Research Ethics with Vulnerable Groups: Ethics in Practice and Procedure.” Gender, Place & Culture 29 (7): 1009–1030. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2021.1994932.

- Robertson, T., and J. Simonsen. 2013. “Participatory Design: An Introduction.” In Routledge Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson, 1–18. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sarria Sanz, C., and A. Alencar. 2020. “Rebuilding the Yanacona Home in the City: The Role of Digital Technologies for Indigenous Place-Making Practices in Bogota, Colombia.” Global Perspectives 1 (1): 13403. doi:10.1525/gp.2020.13403.

- Vasudevan, L., and J. Riina-Ferrie. 2019. “Collaborative Filmmaking and Affective Traces of Belonging.” British Journal of Educational Technology 50 (4): 1560–1572. doi:10.1111/bjet.12808.

- Vera Espinoza, M. 2020. “Lessons from Refugees: Research Ethics in the Context of Resettlement in South America.” Migration and Society 3 (1): 247–253. https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/60683.