ABSTRACT

The China National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC), which produces one-third of the world’s cigarettes, is the largest tobacco company in the world. Over the past 60 years, the CNTC has been focused on supplying a huge domestic market. As the market has become increasingly saturated, and potential foreign competition looms, the company has turned to expansion abroad. This paper examines the ambitions and prospects of the CNTC to ‘go global’. Using Chinese and English language sources, this paper describes the globalisation ambitions of the CNTC, and its global business strategy focused on internal restructuring, brand development and expansion of overseas operations in selected markets. The paper concludes that the company has undergone substantial change over the past two decades and is consequently poised to become a new global player in the tobacco industry. This article is part of the special issue ‘The Emergence of Asian Tobacco Companies: Implications for Global Health Governance’.

Introduction

With nearly one-third of the world’s smokers (300 million), and 40% of global tobacco production (2.5 trillion cigarettes), China has the largest tobacco industry in the world (Li, Citation2012). The state monopoly China National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC) is the fourth largest Chinese company in terms of profit (Li, Citation2012), employing 510,000 people across 33 provinces (China Tobacco, Citationn.d.), and contributing 7–11% of government tax revenues annually (Han, Citation2013). On a global scale, CNTC profits exceed British American Tobacco (BAT), Philip Morris International (PMI) and Altria combined (Bloomberg News, Citation2012). Despite the size of the Chinese industry, given its domestic orientation, analyses of tobacco industry globalisation to date have focused on leading transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) (Lee, Eckhardt, & Holden, Citation2016).

Following accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, and facing growing saturation of the domestic market (Zhou & Cheng, Citation2006), the CNTC declared ambitions to ‘go global’ (Euromonitor, Citation2008). The limited scholarly attention to globalisation and the CNTC to date has come largely from business studies (Wang, Citation2009). This paper examines the global business strategy of the CNTC as a global public health challenge. Using Chinese and English language sources, this paper describes the globalisation ambitions of the CNTC, its global business strategy focused on internal restructuring, brand development and expansion of overseas operations in selected markets. The paper assesses the extent to which this strategy has been successful to date, the likely prospect that China will join the ranks of existing TTCs, and the implications for tobacco control worldwide.

Background

Tobacco was brought to China by trading merchants during the sixteenth century. Leaf cultivation was firmly established by the mid-1800s, and smoking from the late nineteenth century with the automation of cigarette manufacturing. During the first half of the twentieth century, the industry was dominated by BAT with 82% of market share (Tong, Tao, Xue, & Hu, Citation2008), and a handful of domestic companies (Benedict, Citation2011). Political instability and conflict over decades undermined attempts to regulate the industry (STMA, Citation1997).

BAT was required to leave China in 1953 given the industry’s nationalisation following establishment of the People’s Republic of China (Lee, Gilmore, & Collin, Citation2004). The domestic industry grew rapidly, with the building of many small factories, increasing annual cigarette production on average 11% annually between 1949 and 1958 (Benedict, Citation2011). However, the industry was also highly uncoordinated, controlled at the provincial level by local monopoly offices reporting to ministries of light industries, commerce and other financial entities (STMA, Citation1997). The Great Leap Forward (1958–1960) and ensuing famine (1959–1961) slowed production to 5.1% annually (Benedict, Citation2011). In 1963, the China Tobacco Industrial Corporation was established to try to achieve greater efficiencies through centralised management of procurement, production and sales (STMA, Citation1997). Production and revenues rose dramatically, and tobacco taxes remitted increased from 4.1 billion RMB during 1958–1962, to 5.6 billion RMB during 1963–1966 (STMA, Citation1997). The corporation was dismantled in the wake of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 (STMA, Citation1997) and the industry reverted to its former fragmented structure.

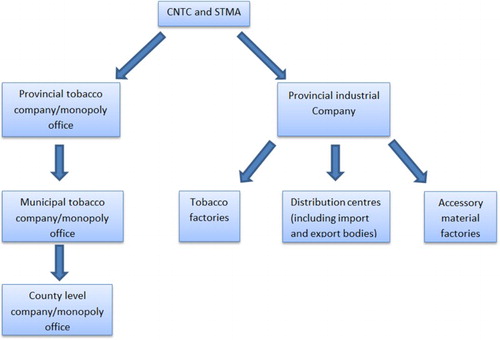

Economic reforms under the Open Door Policy, from the late 1970s, allowed imports of new technology and knowhow (STMA, Citation1997). To reassert central control, the CNTC was formed in 1981 to manage the 28 provincial companies (State Council, Citation1981). Profits and tax revenues were distributed among the central and provincial governments, CNTC and various subsidiaries (State Council, Citation1981). In 1983, the State Council established the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (STMA) as the industry’s administrative and regulatory body (State Council, Citation1983). Formally separate entities, in practice the CNTC and STMA are ‘one institution with two name plates’ (STMA, Citation1997) governing the industry through a vertical bureaucracy (Wang, Citation2009). The CNTC undertakes central planning, manages raw materials, sets regional production quotas for leaf and products, and is the umbrella company for provincial firms. The STMA administers and regulates the national monopoly (STMA, Citation1984), with parallel structures at the provincial level governed by municipal and provincial authorities (Zhou, Citation2004) ().

Figure 1. Structure of the Chinese tobacco industry. Source: Compiled from STMA (Citation1997) and Zhou (Citation2004).

Methods

The paper adopts the framework set out in Lee and Eckhardt (2016) to organise and analyse the factors assessing the global business strategy of CNTC including the key factors driving the strategy, key tactics used, and the extent to which the company has succeeded to date. The primary and secondary data sources were compiled into a chronological narrative according to these three questions.

We began by searching Google Scholar and Baidu Scholar to review the limited scholarly literature on the Chinese tobacco industry from public health, business studies and other relevant fields. Chinese-language secondary literature (dissertations, articles and industry reports) was identified through the China Knowledge Network. These sources were used to map the industry’s history and changes to its structure over time.

To understand the global business strategy of the Chinese industry, we searched the websites of the CNTC (http://www.tobacco.gov.cn), and industry news sites, Tobacco China (http://www.tobaccochina.com), Tobacco Market (http://www.etmoc.com) and China Tobacco (http://www.echinatobacco.com). The China Tobacco Yearbook (1981–2014) was reviewed for information on key strategies and annual industry performance. The China Law Education website was searched for official decrees and statements related to the tobacco industry.

To triangulate Chinese source data, we searched Google and Baidu for news on the globalisation ambitions of the Chinese industry. We also searched other English-language business news sources, notably Euromonitor, Tobacco Journal International and Tobacco Reporter. We sought information on industry restructuring, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), joint ventures (JV), foreign direct investment (FDI), target markets and product development. The searches used the keywords ‘China National Tobacco Corporation’, ‘Chinese tobacco industry’ and specific company names combined, using Boolean terms, with such terms as ‘global*’, ‘strategy’, ‘foreign’, ‘trade’ and ‘investment’. The international database UN Comtrade (http://comtrade.un.org/) was used to compile Chinese tobacco trade data.

The paper does not draw on industry documents held in the Truth Tobacco Documents Library. These were previously searched to understand market access strategy by TTCs into China (Holden, Lee, Gilmore, Fooks, & Wander, Citation2010; Lee et al., Citation2004; Lee & Collin, Citation2006; Zhong & Yano, Citation2007). While mentioning CNTC as a TTC competitor, the collection is limited to TTC documents dating primarily before the mid-2000s. Thus, they do not cover the CNTC’s expansion plans.

While English and Chinese language sources are consulted, the available data have three limitations. First, as a government-controlled monopoly, the CNTC is not required to report as a public company (e.g. annual report to shareholders). Chinese data are thus limited in scope and content. Second, official Chinese data are government controlled and not verified by independent sources. Much secondary analyses, in turn, are based on official sources. Third, we found inconsistencies in data on key indicators from different sources. To address these three caveats, triangulation of multiple data sources was undertaken where possible. The compiling of trend data drew on the same sources where available for consistency.

Findings

What are the key factors behind the CNTC’s global business strategy?

China’s export-led growth, and status as the ‘world’s factory’ (Zhang, Citation2013), faced growing competition from lower-wage emerging economies by the late 1990s. In 1998, President Jiang Zemin called on Chinese companies (including state-owned enterprises) to improve product development, pursue foreign markets, and establish manufacturing abroad (CCPIT, Citation2007). This policy was named the ‘Go Global’ strategy in 2000 (CCPIT, Citation2007).

Tobacco industry interest in foreign expansion was first raised following China’s signing of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1993. As stated by STMA Director Jiang Ming, to ensure long-term development of the tobacco industry, ‘we must follow a “Big Tobacco” strategy’ (Huang, Citation1993). He envisioned the establishment of overseas companies and diversification into non-tobacco sectors (Huang, Citation1993). Similarly, CNTC Director Xun Xinghua declared that the industry was ‘seizing all opportunities to expand and occupy foreign markets’ (Anon, Citation1993). Given continued exclusion of TTC competition by the Chinese import quota system (Lee et al., Citation2004), and size of the domestic market, initial industry efforts were limited.

The industry anticipated change following WTO accession. As Holden et al. (Citation2010) describe, TTCs pressed hard to access the closed Chinese market during accession negotiations. Import quotas remained in place, but import tariffs were reduced from 70% in 1996 to 25% in 2004, along with opportunities for wider distribution of foreign brands. Tobacco imports rose in value and quantity from 2001 (). Given potential erosion of domestic market share, as in Japan and Taiwan, along with China’s signing and later ratification of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), firmer plans were made to ‘make up for domestic losses overseas’ (Zhou & Cheng, Citation2006). In 2003, the industry was called upon to ‘actively implement the “go global” strategy to establish stable international markets’ (STMA, Citation2004), coinciding with the removal of the requirement for retail permits to sell foreign cigarettes in China (Tong et al., Citation2008).

Table 1. Value and quantity of tobacco product imports 2001–2015.

Applying Dunning and Lundan (Citation2008), the industry can be seen to have shifted sharply since the mid-2000s, from largely domestic focused, to increasingly outward looking in four ways. First, CNTC is a ‘natural resource seeker’, as the industry aims to source quality leaf to bring its products in line with TTC brands. Establishing local leaf procurement companies in key tobacco growing regions of Brazil, Zimbabwe and the USA ensures a steady supply to feed growing industry needs both domestically and abroad. Second, CNTC is a ‘market seeker’. CNTC has been exporting since the 1980s, but the scale and reach of exports since the late 2000s suggests a more concerted strategy. Third, CNTC is an ‘efficiency seeker’, setting up overseas operations in key strategic areas to target-specific markets. Seeking to further decrease operational costs for greater profit margins, CNTC’s overseas operations strive to use locally grown tobacco leaf and hire locals where possible, thereby increasing efficiency through removing cultural and language barriers. The strategic location of major offshore production bases in each region is a clear indication of efficiency seeking. Fourth, CNTC is a ‘strategic asset seeker’, as it monitors foreign markets seeking investment opportunities for business growth through M&A. The CNTC’s globalisation efforts are expected to intensify.

Which global business strategies have CNTC pursued?

The restructuring of the Chinese tobacco industry

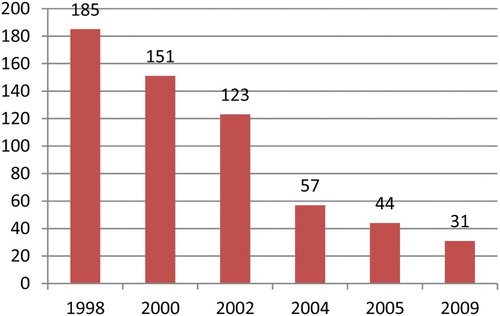

High profits and tax revenues sustained government support in China for cigarette manufacturing at the provincial, municipal and county levels over many decades. Provincial governments also introduced protectionist measures in the 1990s, including near monopolies, to protect local companies regardless of productivity and efficiency (Wang, Citation2009). The result, a crowded and fragmented industry, was seen by the STMA as problematic ahead of WTO accession and foreign competition. Structural reforms, described as ‘grasping the large and letting go of the small’ (Wang, Citation2009), were introduced to boost efficiency, productivity and product quality. Tobacco companies were put into four categories (STMA, Citation1998a):

large firms with annual profits >RMB 100 million (US$12.08 million) and production >500,000 casesFootnote1 of cigarettes (major inter-provincial/regional enterprises);

medium firms with potential production of >300,000 cases annually (major provincial/regional companies);

small firms with production of 100,000–300,000 cases annually (to merge with other firms or close depending on performance); and

poorly performing firms with production of <100,000 cases annually (to declare bankruptcy).

Between 1998 and 2009, this consolidation reduced the number of companies to one-sixth ().

Figure 2. Total number of Chinese tobacco companies (1998–2009). Source: Compiled from Liu and Ren (Citation2009) and STMA (Citation2000, Citation2002, Citation2003, Citation2005, Citation2006).

The industry at the provincial level was also restructured into three distinct entities – industrial companies, tobacco companies and local monopoly bureaus (Zhou, Citation2004). Industrial companies centralise the management of manufacturing and allow pooling of resources among factories (Tong et al., Citation2008). Tobacco companies are concerned with the sale and distribution within the province of all tobacco products regardless of where they are produced. Local monopoly bureaus regulate and administer the industry at the provincial level (Xu & He, Citation2003). This restructuring supported the STMA’s vision of fostering ‘large-scale enterprises, big brands and large markets’ (Zhou, Citation2004). For example, the removal of provincial protectionism allowed provincial manufacturers to sell their brands nationally, fuelling domestic competition and, in turn, product and brand development, and the expansion of successful companies (Wang, Citation2009). Provincial tobacco companies, delinked from manufacturing and now reliant on sales, only purchased products that sold well (Xie, Citation2003). Corporate governance reforms were also accelerated in 2005, with manufacturing facilities becoming limited liability companies led by boards of directors (Liu, Citation2006).

In 2003, Anhui became the first province to implement these reforms by establishing Anhui Tobacco Industrial to manage the assets of five manufacturers (Zhou, Citation2004). The same year the first inter-provincial industrial company was formed, between Sichuan Province and Chongqing city, consolidating their manufacturing into Chuanyu Industrial. In 2004, sixteen industrial companies were established (Li, Citation2006). In 2003, the Beijing Cigarette Factory split from Beijing Tobacco Company to merge, along with the Tianjin Cigarette Factory, with the Shanghai Tobacco Group (STG) (Zhou, Citation2004). In 2008, a ‘merger of two giants’ occurred between Yunnan’s Hongyun and Honghe Groups, forming the Hongyun Honghe Tobacco Group. With annual sales of over 4 million cases, Hongyun Honghe is the world’s fourth largest by sales volume after PMI, BAT and Japan Tobacco International (JTI) (Anon, Citation2008).

The overall vision of provincial reforms has been to establish a three-tiered system, with municipal factories becoming subsidiaries (with legal authority) or branches (without legal authority) of provincial industrial companies, and the latter acting as CNTC subsidiaries (Liu, Citation2006). The aim has been to reduce local government power over the industry, and increase competition across the same tiers in the industry, by dismantling its vertical structure and bureaucracy (Wang, Citation2009). Further reforms under discussion include reduced political involvement from the commercial side of the industry, as opposed to its regulation and administration, and even privatisation (Liu, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2015). However, given the economic and political importance of the industry, including its significant contribution to public revenues, wholesale privatisation is unlikely to precede the pursuit of a global business strategy in the near future (Wang, Citation2015).

Overall, restructuring of the Chinese tobacco industry since the early 2000s has been seen by industry sources as a key strategy for CNTC to become globally competitive. It is believed that CNTC may follow in the footsteps of JTI, eventually pursuing public listing for the most successful firms, but remaining part owned by government (Anon, Citation2003). Five domestic giants from three regions have emerged through these reforms: Hongta Group and Hongyun Honghe Tobacco Group in Yunnan Province; STG; and Changsha Tobacco Group and Changde Group in Hunan Province (Wang, Citation2009).

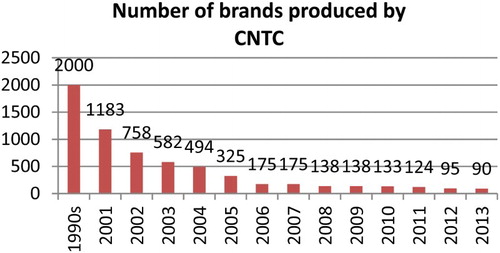

Product development: brand consolidation and premiumisation

To enhance global competitiveness, Chinese product development involved three strategies: consolidation of brands into a smaller number with mass appeal; adaptation to appeal to foreign markets; and higher value-added premium products. First, historically, a large number of Chinese companies manufactured thousands of local brands at many different price points (Anon, Citation2014). The number of brands was dramatically reduced, to a few with broader appeal, to improve economies of scale and enable marketing abroad. In 2001, STMA selected 36 brands to support through advantageous policies such as priority access to raw materials and technology. The result was an increase to 11% market share within two years (Zeng, Citation2010).

In 2004, STMA announced plans to limit mid- and higher-priced brands to one hundred within three years (STMA, Citation2004). In 2006, this became known as the ‘two by ten’ strategy with plans to have ten large-scale manufacturers produce ten key brands. In 2007, the so-called ‘two leaps’ was emphasised whereby leading provincial brands were encouraged to enter the national market, and strong national brands to enter the global market (Zeng, Citation2010). This was followed in 2010 by the ‘235’ strategy, to develop two brands selling over five million cases; three brands selling over 3 million cases; and five brands selling over 2 million cases (Zeng, Citation2010), and the ‘461’ strategy, with 12 brands to earn revenues over RMB 40 billion (US$5.87 billion), 6 brands over RMB 60 billion (US$8.80 billion) and 1 brand over RMB 100 billion (US$14.7 billion) by 2015 (Zeng, Citation2010).

In 2013, consolidation had reduced cigarette brands from around 2000 in the late 1990s to 90 (). These remaining brands held larger domestic market share. In 2010, seven brands exceeded US$4.4 billion in annual sales, with five brands – Hongtashan, Baisha, Double Happiness, Furongwang and Chungwa, seeking to sell over 5 million cases (US$14.7 billion) annually (Zeng, Citation2010). As well as fending off global brands such as Marlboro in the domestic market, consolidation aimed to create global Chinese brands for foreign markets. In 2013, CNTC sold 70 billion sticks overseas comprising 74 brands. This was reduced to 30 brands by 2014, with many tailored to key markets (Feng, Citation2014a).

Figure 3. Number of CNTC brands (1990s–2013). Source: Anon (Citation2014).

Alongside consolidation, CNTC has pursued a strategy of premiumisation since 2008. In China, luxury brand cigarettes are an important currency of guanxi (a system of social networks and influential relationships to facilitate business and other dealings). Premium brands enjoyed rising sales, as the economy boomed, with manufacturers releasing luxury versions of familiar brands or new brands. In 2012, luxury brands sold over 2 million cases and enjoyed a 20% increase from the previous year (Anon, Citation2013a). Despite an STMA price cap, anti-corruption measures and public smoking ban for government officials (China News, Citation2014), production and sale of luxury brands continued to rise (Feng, Citation2014b). Market share grew, from 6% in 2007 to 25.2% in 2014, the only segment to see growth in 2014. Mid-priced products saw modest growth, while the economy segment fell dramatically from 59.7% to 28.3% during the same period (Euromonitor, Citation2013, Citation2015). Overseas, premium brands are seen as key to efforts to improve the perceived quality of Chinese products (Feng, Citation2014b). CNTC documents suggest that it will seek to establish global brands comparable in quality and price to TTCs brands (Lu, Citation2014).

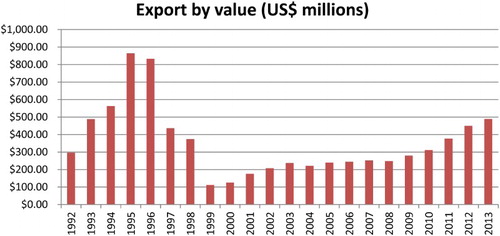

Expansion of Chinese cigarette exports

Chinese cigarette exports date from the creation of the China Shenzhen Tobacco Trading Centre in 1984. In 1985, the China National Tobacco Import Export Corporation (CNTIEC) was then formed to oversee trade of tobacco products, technology and accessories, as well as international economic cooperation (STMA, Citation1997). However, exports remained small-scale and distributed across many different companies. From 1991 to 1995, CNTC exported over 100 brands to 37 countries including Virginia (flue-cured) cigarettes to Southeast Asia; blended cigarettes to Europe, the USA, Russia and Africa; and herbal cigarettes to Korea and Japan (STMA, Citation1996). The restructuring of the industry from the mid-1990s saw the closure of several export arms of provincial companies (STMA, Citation1998b). Focusing on quality over quantity, underperforming brands and markets were subsequently dropped, and exports declined to an all-time low in 1998–1999 (STMA, Citation2000).

Looming WTO access prompted a more strategic approach to exports. In 2000, the CNTIEC was reorganised and renamed the China Tobacco Import Export Group (CNTIEG). CNTIEG became the parent company of all CNTC overseas operations and export branches of provincial companies (STMA, Citation2005). In 2008, CNTIEG became China Tobacco International (CTI), focused on supporting ‘CNTC’s strategic need to “go global”’ (Wang, Citation2008). In 2011 the first annual meeting on tobacco market expansion was held which adopted a three-step strategy for export growth: (a) market entry and establishment of a distribution network; (b) licensed production by local manufacturers; and (c) establishment of local production facilities (Ju, Citation2011). At the 2013 meeting, five export manufacturing facilities in Shanghai, Guangdong, Yunnan, Hunan and Zhejiang, and Jilin were announced (Anon, Citation2013b), each focused on nearby regions and ‘cultural advantage’. For example, Yunnan Tobacco would target Southeast Asia (Zhu & Tian, Citation2007).

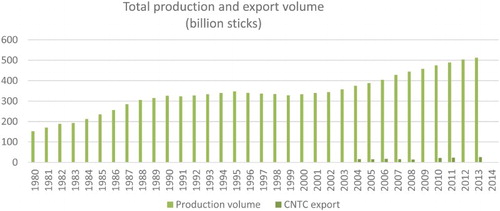

Chinese exports, as a proportion of total production, remain relatively small but rising since 2004, from 4.35% to 5.08% by 2013. However, by volume this represents a 60% increase from 16.3 to 26 billion sticks (STMA, Citation2005, Citation2014), surpassing Korean company KT&G to become the world’s fifth largest exporter (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2013). Export value (unadjusted) has also increased, from US$100 million in 1999 to US$500 million in 2013 (). In 2015, a link between the ‘One Belt, One Road’ and ‘Go Global’ strategy was announced to improve CNTC’s access foreign markets (Qing, Citation2015). This initiative refers to the extension of the so-called Silk Road Economic Belt, linking western China with Europe through Central Asia, to the new Maritime Silk Road from China’s southern coast to Europe via North Africa and Southeast Asia (Knowler, Citation2015).

Figure 4. Value of tobacco exports, 1992–2013 (US$ millions). Source: Compiled from UN Comtrade Database (Citation2015).

Gaining access to foreign technology and knowhow

TTCs sought to negotiate a return to the Chinese market, as the ‘ultimate prize’, from the 1980s (O’Sullivan & Chapman, Citation2000). While they pressed for full or part-ownership of local manufacturing, the STMA limited JVs to leaf production and licensed manufacturing of foreign brands by Chinese companies (Lee et al., Citation2004). For example, RJR licensed the Xiamen Cigarette Factory to produce Camel cigarettes in 1980 (Lin, Citation1984). In 1991, BAT agreed to license manufacturing of Derby by the Wuhu Cigarette Factory, while Rothmans was licensed by the Shandong-Rothmans JV (Lai, Citation2009). In 1993 PMI signed licensing agreements for Marlboro (Shanghai Cigarette Factory) and other brands (Lai, Citation2009; PMI, Citation1993). In 1999, JTI licensed production of Mild Seven to Shanghai Gaoyang International Tobacco Company (Lai, Citation2009). Imperial Tobacco’s West brand was licensed to Hongta Group in 2003 (Hongta Group, Citation2014).

From a Chinese perspective, licensing allowed local firms to access new technology and knowhow (Lai, Citation2009), while keeping the industry under Chinese control. This strategy is evident in agreements with TTCs supporting the development of Chinese brands. In 1986, Huamei was established in Xiamen’s Special Economic Zone (SEZ) as an equity JV between Xiamen Cigarette Factory and RJR, developing Golden Bridge as a leading brand by 1989 (Lai, Citation2009). In 1996 BAT agreed to support brand development (Lovell White Durrant, Citation1996) of Guangzhou Cigarette Factory’s Cocopalm and Guiyang Cigarette Factory’s Huangguoshu Waterfalls (Lai, Citation2009). BAT and Yunnan Tobacco Company agreed in 1999 to ‘jointly develop and produce blended cigarettes’, in addition to leaf cultivation and training (BAT, Citation1999). In 2000 RJR agreed to develop a jointly-owned brand for sale in China and the US (RJR, Citation2000). TTC hopes that these agreements would lead to greater market access were disappointed in 2006 when the government announced a ban on all new manufacturing facilities, including JVs with foreign companies, as part of stronger tobacco control measures (Ding, Citation2006). As PM realised, CNTC only wants ‘to acquire foreign technology and management skills without giving away much to foreigners’ (PM, Citation2002).

Establishing foreign-based operations

Foreign operations established during the early 1990s were limited in scope and focused on Asia, notably Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar. Hong Kong and Macau received substantial investment due to their SEZ status and proximity to the mainland. This began to change in the mid-2000s as the CNTC looked to expand foreign production and distribution of Chinese brands. Lacking its own networks, JVs were formed with TTCs to produce and distribute Chinese cigarettes abroad (CTI, Citation2014a; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2013). In 2003, STG and Gallahers signed reciprocal trademark license agreements and, the following year, launched each other’s brands in China and Russia (Gallaher, Citation2004). A ‘long-term strategic cooperative partnership’ with PMI agreed in 2005 involves licensed production and distribution of Marlboro in China, and the establishment of jointly-owned China Tobacco Philip Morris International (CTPMI) to launch and distribute Chinese brands in foreign markets. Based in Switzerland, CTPMI launched three so-called ‘heritage brands’ (RGD, Dubliss, and Harmony) in 2008, using PMI’s distribution networks in Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America (Tobacco Free Kids, Citation2010). In 2012, CTPMI opened an office in the Democratic Republic of Congo to launch heritage brands (CTI, Citation2014c). Similarly, CNTC partnered with BAT to form China Tobacco British American Tobacco (CTBAT) International in 2013, with worldwide rights to BAT brand State Express 555, and Chinese brand Double Happiness outside of China (BAT, Citation2013). Shanghai Tobacco licensed production of Zhongnanhai, Golden Deer and Red Double Happiness to JTI for distribution in Russia (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2013). Joint brands include Win and Xingxin, developed by Hongyun Honghe Group and Myanmar’s Fu Xing Brothers Group (Lei, Citation2013), and Zhongnanhai (Totem) developed by Shanghai Tobacco and the Chinese-Mongolian JV (CTI, Citation2014a). At the time of writing there are negotiations for a similar JV between Yunnan Tobacco Industrial and Imperial Tobacco (Yu, Citation2015).

It is expected that CNTC will soon progress to M&As of small and medium-sized foreign tobacco companies, mimicking TTCs such as JTI and Imperial Tobacco (Qing, Citation2015). For example, there were negotiations between Hongta Group and Donskoy Tabak in 2012 for Hongta’s purchase of 0.5% share of Russia’s largest national tobacco manufacturer. This would permit entry of Hongta brands into the Russian market, produced and distributed by Donskoy Tabak (Anon, Citation2012). While negotiations appear to have been unsuccessful, industry analysts predict that the CNTC’s ‘massive current account surplus built up over years means that no company is too large to be purchased for cash’ (Euromonitor, Citation2008), a sentiment echoed by others (The Economist, Citation2014).

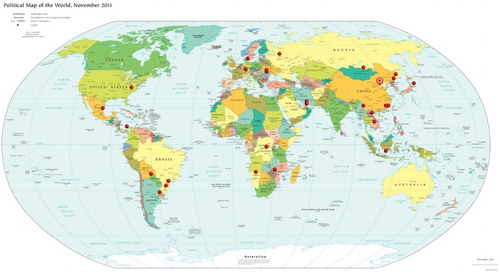

By the late 2000s, Chinese overseas supply chain has also improved. Foreign operations have been established to secure tobacco leaf from Brazil, USA and Zimbabwe. For example, land in the Zambezi region, Namibia has been leased to Namibia Oriental Tobacco to grow tobacco leaf for China, generating much controversy in a country with high levels of food insecurity (Dlamini, Citation2015). Shanghai Tobacco is opening a distribution centre in Singapore, with initial duty-paid target markets of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore, and select duty-free markets within the region (CTI, Citation2014b). There is also rapid growth of Chinese offshore production with over half of the 50.4 billion sticks of Chinese cigarettes sold internationally (2011) produced overseas (STMA, Citation2012). This increased to 44 billion sticks (two-thirds of global sales) in 2013 (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2013). Located in strategically important geographical regions, these facilities (marked with asterisk in ) reflect expansion plans in Latin America, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. For instance, Viniton Group and Lao Liaozhong Hongta Fortune Tobacco have established production and distribution bases in Southeast Asia. The CTIEC targets Europe, while United Overseas (Panama) produces Chinese brands for the Americas (CTI, Citation2014, Citation2014c). The industry’s focus on expanding overseas production is expected to continue, encouraged by favourable government policies (Feng, Citation2014a).

Table 2. Tobacco-related foreign-based operations by China, 1989–2015.

lists CNTC’s portfolio of foreign operations which include distribution offices, manufacturing plants, production and distribution bases, tobacco leaf procurement, and machinery and accessory materials. Led by China Tobacco International, each investment is affiliated with a provincial industrial company (Guangdong Tobacco Industrial and Viniton Group), or municipal subsidiary (Hongyun Honghe Group and Myanmar Kokang Factory). The foreign operation produces brands of the respective parent companies or licensed production of other companies. Importantly, FDI has been coordinated to minimise competition among Chinese companies on the global market (CTI, Citation2014c).

How globalised is CNTC to date?

Using indicators set out in Lee and Eckhardt (Citation2016), and Lee et al. (Citation2016), for which there is available data, CNTC appears poised to ‘go global’, but its global business strategy is unlikely to follow the pattern of existing TTCs. Most notable has been the domestic restructuring of the industry, as a whole, and of individual firms. There has been substantial consolidation, to transform a highly fragmented and inefficient industry, into fewer, larger and more competitive firms with clearer geographical (national, provincial and municipal), functional (manufacturing, sales and administration) and regulatory (central and provincial STMAs) delineation. Supported by favourable government policies and substantial resources, the restructured domestic industry has achieved greater economies of scale. Moreover, while consolidating to compete with TTCs, the Chinese industry has been reconfigured in ways that minimise competition among domestic firms. The resultant structure potentially dwarfs existing TTCs and serves as a springboard for globalisation.

Changes to ownership structure do not appear to be part of Chinese global business strategy for the tobacco industry. The industry is likely to remain state-owned and controlled for the foreseeable future. As observed by industry analysts,

As domestic firms in China mainly dominate the local cigarette industry, the industry’s globalization level is relatively low and is expected to remain low in the future … .The industry’s globalization level is low due to the low foreign ownership levels of the industry’s firms in China. In 2014, the share of revenue contributed by foreign-funded enterprises (including those from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan) is expected to be only 0.1% of the industry’s total. The Chinese Government largely controls China’s tobacco sector and limits the investment of foreign manufacturers in China. (IBIS World, Citationn.d.)

Figure 5. Map of distribution of CNTC’s foreign-based operations. Source: Compiled from BAT (Citation2013), Hongta Group (Citation2010), STMA (Citation2006, Citation2009, Citation2012), Tobacco-free Kids (Citation2010).

Another indicator of globalisation is product development to promote a small number of Chinese ‘heritage’ brands overseas, as well as premium brands. These are likely to appeal to overseas Chinese, rather than serve as global brands, given their close affinity with Chinese cultural tastes and practices. The development of new brands, to appeal to a wider global market beyond Chinese diasporas, is likely to increase via JVs with existing TTCs.

Finally, trends in exports suggest an increasingly outward looking Chinese industry. Exports have grown rapidly by volume () following the establishment of five export manufacturing facilities in 2013. A target of 8 million cases by 2020 was declared in 2014 with the aim of catching the sales volumes of leading TTCs (Anon, Citation2013b; Lu, Citation2014). This data exclude overseas production which has also risen sharply since 2008, reaching 1.57 million cases in 2014 (Qing, Citation2015). Export markets have also begun to diversify beyond Asia. While Asia remains a priority region, with the largest number of overseas operations, markets in Latin America, Eastern Europe and the Middle East are clear targets.

Figure 6. CNTC annual production and export in billions of sticks (1980–2013). Source: Compiled from STMA (Citation1996–2014).

Discussion

Previous analyses of the global tobacco industry recognise the importance of, but generally exclude, the CNTC because of its strong domestic focus. The findings of this paper suggest, however, that the Chinese industry has been steadily positioning itself to become a global player since the late 1990s. While the Chinese tobacco industry is likely to remain, in the medium term, primarily dependent on its huge domestic market of 350 million smokers, indicators suggest the emergence of a new Chinese TTC in the next decade.

This analysis shows that the ‘go global’ ambitions of the Chinese tobacco industry have been spurred by both internal and external forces. Domestically, the market has neared saturation among adult males with 53% smoking prevalence rates. Future growth is likely to come from population growth and increasing female smoking rates (currently 2.4% for adult females). However, ratification and implementation of the FCTC since 2005 has increased support for the adoption of stronger tobacco control measures, albeit tempered by weak political will and enforcement. Although important changes have been made to strengthen tobacco control legislation, ‘major gaps still exist compared with FCTC requirements’ (Li, Ma, & Xi, Citation2016).

Externally, following WTO accession in 2001, it was anticipated that market opening would bring greater foreign competition like in other Asian countries. This, in turn, would lead to a gradual shrinking of domestic market share. To date, however, the Chinese government has retained a firm grip on the industry and market access, limiting JVs to technology transfers and leaf development and, more recently, reciprocal production and distribution agreements. More influential has been the broader support, in Chinese economic policy, for the ‘go global’ strategy as key to the country’s emergence as a global economic superpower. The sheer size of the Chinese tobacco industry compared to existing TTCs, and thus its potential to generate significant foreign earnings, has prompted the government to promote the industry’s expansion overseas.

If even partially realised, the global ambitions of the Chinese tobacco industry will have profound impacts for public health. The Chinese industry is advantaged by sheer size, weak domestic regulation and government support for overseas expansion. If successful, this will lead to increased global competition on price, new products and intensified marketing, all resulting in increased tobacco consumption. Beyond the WTO, there is much uncertainty to how tobacco will be handled in key negotiations for major trade and investment agreements such as the Trans Pacific Partnership. As CNTC increasingly mimics the globalisation strategies of TTCs, there is a need to now include China, along with other emerging TTCs, into global tobacco control efforts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jennifer Fang http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2676-8571

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. One case contains 50,000 sticks of cigarettes

References

- Anon. (1993, April 1). 寻兴华同志在全国烟草工作会议上的总结讲话(摘要) [Summary of Xinghua Xun’s speech during the National Tobacco Working Meeting]. Retrieved from http://www.echinatobacco.com/101588/102220/102455/102459/36131.html

- Anon. (2003, April 22). Breaking up tobacco monopoly. Tobacco Journal International. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccojournal.com/Breaking_up_tobacco_monopoly.X3113.0.html

- Anon. (2008, November 3). Merger of tobacco giants approved. Tobacco Journal International. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccojournal.com/Merger_of_tobacco_giants_approved.49303.0.html

- Anon. (2012, June 27). Hongta eyes expansion into Russian market through Donskoy tie-up. Tobacco Campaign. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccocampaign.com/hongta-eyes-expansion-russian-market-donskoy-tie-up

- Anon. (2013a, November 23). 从价格标榜到价值标杆:高端品牌的成长解构与发展预期 [From price to value: the growth and development outlook on luxury brands]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/news/analysis/wu/201311/20131119154531_595262.shtml

- Anon. (2013b, December 23). 2013年烟草行业拓展国际市场工作会议在北京召开 [2013 tobacco industry working meeting on global market expansion held in Beijing]. Retrieved from Government of PRC http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2013-12/23/content_2552890.htm

- Anon. (2014, August 6). 中国卷烟品牌市场竞争分析 [Analysis of market competitiveness of Chinese cigarette brands]. Tobacco Market. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/market/looklist.asp?id=31733

- BAT. (1999, May 18). Difficulties encountered in economic development of Yunnan Province. Retrieved from Legacy Tobacco Documents Library http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yjk23a99/pdf

- BAT. (2013, August 30). CTBAT International Limited has officially commenced business operations. Retrieved from BAT http://www.bat.com/group/sites/UK__9D9KCY.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO9B3BUY?opendocument

- Benedict, C. (2011). Golden-silk smoke: A history of tobacco in China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bloomberg News. (2012, March 6). China’s tobacco monopoly bigger by profit than HSBC. Bloomberg News. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-06/china-s-tobacco-monopoly-bigger-by-profit-than-hsbc.html

- China Council for the Promotion of International Trade. (2007, January). 我国‘走出去’战略的形成 [Formation of China’s ‘Go Global’ strategy]. Retrieved from http://oldwww.ccpit.org/Contents/Channel_1276/2007/0327/30814/content_30814.htm

- China News. (2014, March 6). 国家烟草专卖局局长谈”禁烟令”:高端烟价位下降 [STMA director on Smoking ban: declining prices of luxury brands]. Tobacco Market. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/gedi/gedilist.asp?news_id=62289

- China Tobacco. (n.d.). 中国烟草行业概况 [Profile of the Chinese tobacco industry]. Retrieved from http://www.tobacco.gov.cn/html/10/1004.html

- CTI (2014a). 境外卷烟产销基地建设季报 (第四期) [Establishing offshore cigarette production bases: quarterly report (fourth issue)]. Retrieved from http://www.cntiegc.com/src/ewebeditor/uploadfile/20150122102319140.pdf

- CTI (2014b). 境外卷烟产销基地建设季报(第三期) [Establishing offshore cigarette production bases: quarterly report (third issue)]. Retrieved from http://www.cntiegc.com/src/ewebeditor/uploadfile/20141023075648497.pdf

- CTI (2014c). 境外卷烟产销基地建设季报(第二期) [Establishing offshore cigarette production bases: quarterly report (second issue)]. Retrieved from http://www.cntiegc.com/src/2014-08/10006913.jsp?purview=1,2,3,

- CTIEC. (n.d.). 中烟国际欧洲有限公司 [China Tobacco International Europe Company]. Retrieved from http://www.ctiec.cc/Default-1.aspx

- Ding, X. (2006, February 8). 中国正积极实施⟪烟草控制框架公约⟫ [China is actively implementing the FCTC]. Retrieved from http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/fztd/fzsh/2006-02/08/content_344513.htm

- Dlamini, M. (2015, July 28). Tobacco Farm: what’s in it for Namibians? The Namibian. Retrieved from http://www.namibian.com.na/indexx.php?archive_id=139937&page_type=archive_story_detail&page=1

- Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy (2nd ed.). London: Edward Elgar.

- Euromonitor International. (2008, November 20). China targets global expansion via acquisition and flagship brands. Retrieved from http://www.portal.euromonitor.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/portal/analysis/tab

- Euromonitor International. (2013, October). Cigarettes in China. Retrieved from http://www.portal.euromonitor.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/portal/analysis/tab

- Euromonitor International. (2015, August). Cigarettes in China. Retrieved from http://www.portal.euromonitor.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/portal/analysis/tab

- Feng, J. (2014a, February 19). 瞄准重点目标 全力谋求突破 - 就烟草行业拓展国际市场工作访国家局副局长李克明 [Focusing on key objectives to achieve breakthrough: an interview with State Tobacco Monopoly Administration’s Deputy-director Li Keming on the industry’s global market expansion]. East Tobacco New. Retrieved from http://www.eastobacco.com/zxbk/gjjdzcybdj/qt/201402/t20140219_318938.html

- Feng, W. (2014b, September 11). 中式高价位烟卷阵营的四大支柱力量 [The four pillars of the Chinese premium tobacco segment]. Tobacco Market. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/market/looklist.asp?id=31935

- Gallaher. (2004, May 27). Shanghai tobacco and Gallaher launch brands in China and Russia. News release. Retrieved from http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1037333/000102123104000366/b752037-6k.htm

- Han, Y. (2013, September 1). 烟草税利对国家财政贡献的分析 [An analysis of tobacco industry’s contribution to government revenue]. China Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.echinatobacco.com/zhongguoyancao/2013-09/01/content_416175.htm

- Holden, C., Lee, K., Gilmore, A., Fooks, G., & Wander, N. (2010). Trade policy, health, and corporate influence: British American Tobacco and China’s Accession to the World Trade Organization. International Journal of Health Services, 40(3), 421–441. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.3.c

- Hongta Group. (2010, November 22). Hongta Group is striving to establish world-leading brand. Tobacco Market. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/eng/looklist.asp?id=399

- Hongta Group. (2014). 大事记 [Major events]. Retrieved from http://www.hongta.com/cn/culture/history/chronicle/2003/

- Huang, Y. D. (1993, April 1). 适应市场经济发展 实行”五个转变” [Implementing five changes to adapt to market developments]. China Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.echinatobacco.com/101588/102220/102455/102459/36142.html

- IBISWorld. (n.d.). Cigarette manufacturing in China: Competitive landscape. Retrieved from http://clients1.ibisworld.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/reports/cn/industry/competitivelandscape.aspx?entid=167

- Ju, X. (2011, May 24). 姜成康在烟草行业拓展国际市场工作会议上要求进一步明确现阶段主要任务 增强拓展国际市场动力与活力李克明作工作报告 [Tobacco industry working meeting on global market expansion]. Retrieved from http://www.tobacco.gov.cn/html/30/3004/3768393_n.html

- Knowler, G. (2015, July 3). Investment floods into China’s One Belt, One Road strategy. Journal of Commerce. Retrieved from http://www.joc.com/international-trade-news/investment-floods-china%E2%80%99s-one-belt-one-road-strategy_20150703.html

- Lai, C. (2009, September 20). 华美:改革开放大潮中的中外合资卷烟企业 [Huamei: A tobacco industry joint venture during economic reforms]. China Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.echinatobacco.com/101588/102041/102524/43525.html

- Lee, K., & Collin, J. (2006). ‘Key to the future’: British American Tobacco and cigarette smuggling in China. PLoS Medicine, 3(7), 228–237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030228

- Lee, K., Eckhardt, J. (2016). The globalisation strategies of five Asian tobacco companies: An analytical framework. Global Public Health. doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1251604

- Lee, K., Eckhardt, J., & Holden, C. (2016). Tobacco industry globalization and global health governance: Towards an interdisciplinary research agenda. Palgrave Communications, 2, 16037. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2016.37.

- Lee, K., Gilmore, A., & Collin, J. (2004). Breaking and re-entering: British American tobacco in China 1979–2000. Tobacco Control, 13(Supp II), ii89–95.

- Lei, H. T. (2013, March 25). 红云红河集团WIN牌卷烟新品在仰光成功上市 [Hongyun Honghe Group launches new Win brand]. Retrieved from Tobacco China: http://www.tobaccochina.com/news/China/industry/20133/2013322154330_560563.shtml

- Li, C. (2006, June 13). 中国烟草行业改革进程的人事布局 [Progress of Chinese tobacco industry reforms, part 1]. Retrieved from Tobacco China http://www.tobaccochina.com/management/watch/enterprise/20066/2006613000_191333.shtml

- Li, C. (2012). The political mapping of China’s Tobacco industry and anti-smoking campaign. Washington, DC: Brookings.

- Li, S., Ma, C., & Xi, B. (2016). Tobacco control in China: still a long way to go. The Lancet, 387(10026), 1375–1376. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30080-0

- Lin, M. K. (1984). 引进国外先进技术的”窗口”——厦门卷烟厂与”雷诺士”合作生产”骆驼牌”香烟的启示 [‘Window’ of foreign technology transfer – lessons from Xiamen Cigarette Factory’s licensed production of Camel cigarettes]. Retrieved from http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-FLJS198402005.htm

- Liu, X. (2006, December 14). 卷烟工业企业公司法人治理结构初探 [Exploring the corporate governance structure of cigarette manufacturing firms]. Tobacco Market. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/look/looklist.asp?id=6303

- Liu, F. (2014, December 18). 关于新常态下烟草行业几个改革问题的思考 [Thoughts reforms of the tobacco industry]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/revision/takematter/wu/201412/201412884411_652574.shtml

- Liu, H., & Ren, X. (2009, September 4). 世界烟草企业兼并重组对中国烟草工业的机遇与挑战 [Merging and restructuring of the world tobacco industry and its opportunities and challenges to the Chinese industry]. Tobacco Market. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/look/looklist.asp?id=19779

- Lovell White Durrant. (1996, June 29). The China National Tobacco Corporation and BAT Far East Holdings Limited. Retrieved from Legacy Tobacco Documents Library: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nqo04a99/pdf

- Lu, Y. M. (2014, February 1). ‘ 三大课题’定音 [Setting the stage for ‘three subjects]’. China Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.echinatobacco.com/zhongguoyancao/2014-02/01/content_438225.htm

- MOFCOM. (2015, August 21). 王卫华代表考察湖南中烟公司巴拿马工厂 [Wang Weihua visits Hunan Tobacco Industrial’s Panama factory]. Retrieved from http://panama.mofcom.gov.cn/article/swfalv/201508/20150801087520.shtml

- Namibia Oriental Tobacco. (n.d.). 关于我们 [About us]. Retrieved from http://www.namtobacco.com/LM_gywm

- O’Sullivan, B. & Chapman, S. (2000). Eyes on the prize: Transnational tobacco companies in China 1976–1997. Tobacco Control, 9, 292–302. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.292

- Philip Morris. (2002, February 1). China-Vision 2000+. Retrieved from Legacy Tobacco Documents Library: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zoq19e00/pdf

- PMI. (1993, October 19). Board presentation – opening. Retrieved from Legacy Tobacco Documents Library: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zwd42e00/pdf

- Qing, H. (2015, August 6). 中国烟草”走出去”的文化自信与文化转型 [CNTC’s cultural confidence and cultural transformation to ‘go global’]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/revision/takematter/wu/20158/2015838234_686111.shtml

- RJ Reynolds. (2000, March 10). Memorandum of understanding. Party A: China National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC). Party B: RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJRT). Retrieved from Legaco Tobacco Documents Library: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kmf20d00/pdf

- State Council. (1981, May 18). 国务院批转轻工业部关于实行烟草专营的报告的通知 [State Council approves the Ministry of Light Technology’s tobacco monopoly]. Retrieved from http://www.chinalawedu.com/falvfagui/fg22016/12453.shtml

- State Council. (1983, September 23). 烟草专卖条例 [Tobacco Monopoly Regulations]. Retrieved from http://www.chinalawedu.com/falvfagui/fg22016/12441.shtml

- STMA. (1984, September 10). 烟草专卖条例施行细则 [Implementing Tobacco Monopoly]. Retrieved from http://www.chinalawedu.com/falvfagui/fg22016/54733.shtml

- STMA. (1996). 中国烟草年鉴1991–1995 [China Tobacco Almanac 1991–1995]. Beijing: China Economics Publishing House.

- STMA. (1997). 中国烟草年鉴1981–1990 [China Tobacco Almanac 1981–1990]. Beijing: China Economics Publishing House.

- STMA. (1998a, May 12). 国家烟草专卖局关于烟草行业卷烟工业企业组织结构调整的实施意见 [STMA’s statement on restructuring the of the tobacco industry]. China Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.tobacco.gov.cn/html/27/2701/270114/766153_n.html

- STMA. (1998b). 中国烟草年鉴1996–1997 [China Tobacco Almanac 1996–1997]. Beijing: China Economics Publishing House.

- STMA. (2000). 中国烟草年鉴1998–1999 [China Tobacco Almanac 1998–1999]. Beijing: China Economics Publishing House.

- STMA. (2002). 中国烟草年鉴2001 [China Tobacco Almanac 2001]. Beijing: China Economic Publishing House.

- STMA. (2003). 中国烟草年鉴 2002 [China Tobacco Almanac 2000]. Beijing: China Economic Publishing House.

- STMA. (2004, August 19). 国家烟草专卖局关于印发⟪卷烟产品百牌号目录⟫的通知 [STMA’s notice on the announcement of ‘One hundred brands list]’. Retrieved from http://www.chinalawedu.com/news/1200/22016/22032/22501/2006/3/zh30159194236002205-0.htm

- STMA. (2005). 中国烟草年鉴2004 [China Tobacco Almanac 2004]. Beijing: China Economic Publishing House.

- STMA. (2006). 中国烟草年鉴2005 [China Tobacco Almanac 2005]. Beijing: China Economic Publishing House.

- STMA. (2009). 中国烟草年鉴2008 [China Tobacco Almanac 2008]. Beijing: China Economics Publishing House.

- STMA. (2012). 中国烟草年鉴2011–2012 [China Tobacco Almanac 2011–2012]. Beijing: Science and Technology of China Press.

- STMA. (2014). 中国烟草年鉴2013 [China Tobacco Almanac 2013]. Beijing: Science and Technology Press of China.

- The Economist. (2014, July 19). An irresistible urge to merge. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/news/business/21607827-big-american-deal-has-global-implications-irresistible-urge-merge

- Tobacco-free Kids. (2010, April). China National Tobacco Corporation and Philip Morris International’s partnership. Retrieved from http://global.tobaccofreekids.org/files/pdfs/en/IW_cntc_pmi_bg.pdf

- Tong, E., Tao, M., Xue, Q., & Hu, T. (2008). China’s Tobacco industry and the world trade organization. In T. Hu (Ed.), Tobacco Control Policy Analysis in China (pp. 211–258). River Edge, NJ: World Scientific.

- Trade Map. (2016). China tobacco imports [data file]. Retrieved from: http://www.trademap.org/Product_SelCountry_TS.aspx

- UN Comtrade Database. (2015). China tobacco export [data file]. Retrieved from: http://comtrade.un.org/data/

- United Castle America. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved from: http://unitedcastle.com.mx/aboutus.html

- Wang, J. M. (2009). Global-market building as state building: China’s entry into the WTO and market reforms of China’s tobacco industry. Theory and Society, 38(2), 165–194. doi: 10.1007/s11186-008-9077-x

- Wang, X. (2008, August 7). 中国烟草国际有限公司揭牌仪式在京举行 [China Tobacco International unveiling ceremony takes place in Beijing]. China Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.tobacco.gov.cn/html/30/3001/643645_n.html

- Wang, K. G. (2015, March 4). 建议烟草行业政企分开 将国家烟草局转为国家控烟局 [Recommendation for removal of state ownership of the tobacco industry, restructuring the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration to National Tobacco Control Bureau]. Legal Daily. Retrieved from http://www.legaldaily.com.cn/index_article/content/2015-03/04/content_5987153.htm?node=5955

- Xie, J. (2003, September 30). 对工商分离改革的认识和思考 [Thoughts on the separation of commerce and manufacture]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/management/Industry/management/20039/2003930000_193484.shtml

- Xu, R., & He, T. (2003, May 27). 湖南烟草行业实现工商分离 [Hunan Tobacco achieves the separation of commerce and manufacture]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/management/Industry/management/20035/2003527000_193898.shtml

- Yu, Y. D. (2015). 把握新常态 立足新起点 努力打造国际市场新的增长点——云南中烟2015年全国会议经验交流材料 [Experience from Yunnan Tobacco Industrial]. Retrieved from http://www.cntiegc.com/src/2015-04/10007804.html

- Zeng, Y. (2010, May 19). 重点骨干品牌谋求”规模与效益”双突破 [Breakthrough in size and efficiency of key brands]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/news/analysis/wu/20105/20105198552_410313.shtml

- Zhang, Y. (2013, January 17). China Begins to Lose Edge as World’s Factory Floor. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323783704578245241751969774

- Zhang, Y., & Zhang, W. (2013, March 6). 树立三个雄心壮志 切实把”走出去”战略变成行动——访中国烟草国际有限公司总经理张本甫 [Interview with China Tobacco International’s CEO]. Retrieved from http://www.yntsti.com/news/Foreign/2014/36/122798.html#

- Zhejiang Tobacco industrial. (2015, July 2). 浙江中烟中印尼合资项目举行签约仪式 [Zhejiang Tobacco Industrial holds signing ceremony of China-Indonesia JV]. Retrieved from http://www.etmoc.com/Firm/looklist.asp?id=22705

- Zhong, F., & Yano, E. (2007). British American Tobacco’s tactics during China’s accession to the World Trade Organization. Tobacco Control, 16(2), 133–137. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018374

- Zhou, Y. (2004, August 10). 中国烟草的工商分离及其困境与根本出路 [Industrial and commercial separation of the Chinese tobacco industry, its challenges and the way forward]. Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/management/Industry/management/200410/2004108000_192491.shtml

- Zhou, R., & Cheng, Y. (2006). WHO 烟草控制框架公约对案及对中国烟草影响对策研究 [Countermeasures to WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and its effects on the Chinese tobacco industry]. Beijing: Economic Science Press.

- Zhu, L., & Tian, P. (2007, January 11). 云南烟草国际有限公司召开一届一次董事会议 (Yunnan Tobacco International holds first board meeting). Tobacco China. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccochina.com/news/China/highlight/20071/2007110161653_240386.shtml