ABSTRACT

The concepts Vivir Bien and Buen Vivir, often translated as ‘living well’ or ‘collective well-being,’ are central to contemporary social medicine reforms in Latin America. Owing to increasing social inequalities, notably in the public healthcare sector, Vivir Bien has regional significance as it redefines the neoliberal development goals from economic improvement to so-called post-neoliberal social goals of harmonious co-existence between society and the physical environment. To examine how this abstract concept is conceptualised, is incorporated into, and shapes state-sponsored public health strategies, I analyze the ‘Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien … !’ (‘Live Clean, Live Healthy, Live Beautiful, Live Well … !’) national campaign in Nicaragua that began in 2013. The campaign promotes normative socio-political ideals around environmental health citizenship, including the adoption of indigenous grammars and solidarity. However, analyses of dozens of interviews and 143 household surveys in four historically impoverished, untidy, and unhygienic communities suggest that the campaign’s discourses do not resonate with citizens or their socio-economic contexts. In highlighting discrepancies between state-sponsored normative sociopolitical ideals and citizens’ lived realities and perspectives, this paper introduces the term ‘post-neoliberal citizenship’ to reflect contemporary – and changing – conceptualizations of health, wellbeing, and citizenship in post-neoliberal Latin America.

Introduction

Governance is inextricably linked to population health and well-being, environmental matters, and development. In Nicaragua, as well as in other ‘New Left’ countries in Latin America (e.g. Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and El Salvador, among others), reducing social inequalities and reframing development discourses, particularly as they relate to health, well-being, and the environment, are at the core of progressive governance changes (see Nading, Citation2014). After nearly a two decades-long absence from office, during which time neoliberal discourses and policies firmly took root and drastically re-organized post-revolutionary Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega, who first governed the country from 1979–1990, was re-elected president in 2006 on a populist and self-described anti-neoliberal platform. In an attempt to move away from – but not entirely replace – neoliberalism, the Ortega administration has adopted several so-called ‘post-neoliberal’ ideals, including emphasis on equality and solidarity, an appreciation of indigeneity, and highlighting social over economic goals (Ettlinger & Hartmann, Citation2015).

This paper examines the emergence of the post-neoliberal concepts Vivir Bien and Buen Vivir, which are commonly translated from Spanish to English as ‘living well’ or ‘collective well-being,’ and the aesthetic concept Vivir Bonito, meaning ‘living beautiful’ or ‘living nice,’ in Nicaraguan state discourses. In particular, this study focuses on the ‘Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien … !’ (‘Live Clean, Live Healthy, Live Beautiful, Live Well … !’) national campaign, which began in 2013. The national campaign, hereafter referred to as Live Beautiful, Live Well,Footnote1 stresses transformation of the practices and ‘culture of everyday life, putting emphasis on the necessary consistency between what we are, what we think and what we do’ (Murillo, Citation2013). Besides focusing on Live Beautiful, Live Well’s practical and material implications (e.g. cleaning up urban environments in order to increase tourism) (Fisher, Citation2016), this study critically examines the socio-political discourses around environmental and public health as well as social life at the core of the campaign. Further, to examine how the national campaign is understood by citizens at the subnational and local spaces it intends to ‘beautify,’ this article analyzes household surveys from four historically impoverished, untidy, and unhygienic communities. In doing so, the article seeks to add to the literature which examines contemporary Latin American social medicine reforms by addressing the emergence of a new form of environmental health citizenship, what is termed here as ‘post-neoliberal citizenship.’

Post-neoliberalism and environmental health governance in latin america

Latin America is widely recognised as ‘the privileged birthplace of neoliberalism’ and ‘a laboratory for neoliberal experiments par excellence’ (Sader, Citation2009, p. 172). Around the world, neoliberalism is a political economic model that regulates economies in favour of free and open markets, liberalises trade, privatises state-owned corporations and services, and curtails social spending (particularly in the healthcare sector) (Harvey, Citation2006). Neoliberal policies have exacerbated social inequalities, notably in the public healthcare sector (Homedes & Ugalde, Citation2005; ISAGS, Citation2012).

In recent years, several countries in the region (e.g. Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Nicaragua, and El Salvador, among others) have proposed, to varying degrees, governance strategies that counter neoliberal hegemony; in response, some academics have coined this new epoch the ‘post-neoliberal’ era.Footnote2 To date, much focus has been paid to post-neoliberalism in terms of macroeconomic policies, including South-South cooperation (Muhr, Citation2013), the nationalisation of the hydrocarbon and mining sectors (Kennemore & Weeks, Citation2011), and the redistribution of capital surplus to social policies (Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009), as well as strengthened state-civil society relations and attempts to democratize decision-making from the bottom-up (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012). Little attention has been paid to the implications of post-neoliberal governance for transforming environmental health governance, of which individual and population behaviours are integral. Therefore, the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign provides an important opportunity to do so.

According to Gudynas (Citation2011b) and Walsh (Citation2010), the concept Vivir Bien ostensibly redefines the primary goal of state-sponsored development efforts from economic improvement to the social goal of ‘living well.’ Led by the political left and indigenous movements, post-neoliberal political economic discourses and strategies are framed by diverse orientations, including twenty-first century socialism and indigenous cosmovisions (Escobar, Citation2010). The concept Vivir Bien is central to the recently rewritten constitutions of Ecuador (2008) (‘Constitución del Ecuador,’ Citation2008) and Bolivia (2009) (‘Constitución de Bolivia,’ Citation2009). In these juridical documents, the Vivir Bien model is a relational vision in that individuals are inextricably linked to society, which is interconnected with broader socio-cultural and environmental processes per indigenous beliefs. For instance, the Preamble of the Ecuadorian Constitution States: ‘We decided to construct a new form of citizen coexistence, in diversity and harmony with nature, to reach buen vivir’ (‘Constitución de Ecuador,’ Citation2008, p. 15). Further, Vivir Bien is deeply tied to national development goals. In Ecuador and in Bolivia, meeting basic needs like access to a healthy environment, education, and housing, which have long been denied to the majority of citizens by colonial and more recently neoliberal development models, are fundamental to securing Vivir Bien and promoting political economic alternatives. Furthermore, Vivir Bien is central to the implementation of contemporary public health and social medicine reforms, including providing state-guaranteed public healthcare, promoting intercultural care, and democratising healthcare decision-making, to reduce long-standing health inequalities in Ecuador, Bolivia, and Venezuela (Hartmann, Citation2016). Despite the concept’s importance to modern governance in the region, our understanding of how Vivir Bien is woven into and alters environmental health discourses and strategies remains limited.

In examining the deployment of the social goal of Vivir Bien alongside Vivir Bonito in Nicaragua, this paper heeds Radcliffe’s call to critically analyze ‘the discourses, institutions, rationales, practices, and forms of rule put into motion by anti-neoliberal political and electoral power’ (Radcliffe, Citation2012, p. 240; see also Ghertner, Citation2010). Hence, the paper investigates the emergence of purported post-neoliberal state ‘governmentalities,’ a term Foucault defines as the study of the mentalities by which governance of populations, their environments, and their relations occur (Foucault, Citation2003, p. 245). For Foucault, his interest lie in understanding the technologies of power that seek to configure the habits, aspirations, and beliefs of individuals and communities, in relation to their environments, with the objective of improving population health (Foucault, Citation2003). Under neoliberalism we see the ‘degovernmentalization’ of the state but not a decline in government (Rose, Citation1996, pp. 40–41). Yet, across Latin America and particularly in Ecuador, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, the post-neoliberal present is characterised by claims of the re-emergence of a strong state in terms of engineering economic policy to social policy (Bebbington & Humphreys Bebbington, Citation2011; Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2009, Citation2012; Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009), strengthening state-society relations through the promotion of democracy and increased involvement of civil society in decision-making (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012), and adopting and promoting alternative conceptualizations regarding well-being and development goals (Escobar, Citation2010; Gudynas, Citation2011b; Walsh, Citation2010).

In the post-neoliberal present, it is necessary to examine the re-‘“governmentalization” of the State’ (Foucault, Citation2000, p. 220) to understand how the state’s use of the concepts Vivir Bien and Vivir Bonito seek to ‘conduct the conduct’ of populations toward alternative social, political, and economic goals. From this perspective and in the context of Nicaragua, I ask: How do post-neoliberal governmentalities seek to alter local socio-political relations, particularly as they pertain to human-environment relations? What kind of citizen subjectivity is produced under contemporary governmentalities? How do persons living in targeted (i.e. impoverished, untidy, and unhygienic) communities perceive the Nicaraguan state’s campaign slogans of living beautiful and living well?

Methods

The evidence presented here draws from state-sponsored primary sources and peer-reviewed academic articles. Examples of official government documents include policy reports, speech transcripts, and development reports. Contemporary sources were located online from the website of the Government of Nicaragua (www.presidencia.gob.ni) as well as that of President Daniel Ortega and the Sandinista party (www.elpueblopresidente.com, www.el19digital.com). Secondary sources, including reports, analyses, and articles, were gathered from the two largest periodicals in Nicaragua – El Nuevo Diario and La Prensa.

In addition, this article draws from semi-structured interviews and household surveys completed during fieldwork stints of one month in 2013 and three months in 2015 in Managua, the capital city and political, cultural, and economic centre of Nicaragua. First, the analysis draws from more than 50 semi-structured interviews with community members and leaders, representatives of NGOs, and state officials. The purpose of the semi-structured interviews was to examine the role of community leaders in realising public health campaigns and changes to environmental health governance over time. Interviews were conducted in the native language of the interviewee (Spanish or English) and varied in length from 45–120 minutes.

Second, to understand citizens’ perceptions of the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign, the household survey was administered in four communities that, since the 1970s, have been heavily involved in the local recycling economy. In many respects, the four surveyed neighbourhoods exemplify the spaces targeted by the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign because the communities are impoverished, untidy, and unhygienic spaces (Hartmann, Citation2018). According to guidelines developed by the Nicaraguan Government and World Bank (INIDE, Citation2015), at the time of the household surveys, an estimated 39% of residents in the surveyed communities lived in poverty, one-half of which lived in extreme poverty; in comparison, 29.6% of all Nicaraguans lived in poverty and 8.3% in extreme poverty, whereas in Managua 11.6% of the population lived in poverty and 1.8% in extreme poverty (Guerrero, Citation2015). These neighbourhoods thus represent an ideal context in which to investigate the implementation of the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign.

In each neighbourhood, I approached homes selected by a computer-based random number generator. The survey addressed a range of topics including household composition, labour, and income; additionally, several open-ended questions gauged perceptions of what it means to live beautiful (vivir bonito) and live well (Vivir Bien). I administered the surveys in Spanish. One or two community residents accompanied me at all times to clarify key points and colloquialisms when pertinent and to assist in making contact with potential research participants. I handwrote survey responses, transcribed data verbatim, grouped responses by categories, and completed all Spanish-to-English translations.

I administered the household questionnaire survey to 146 households in March and April 2015; three participants did not respond to the open-ended questions. Surveys were completed in approximately one half-hour. The total participation rate was approximately 62% (n = 146); 13% of homes refused participation, and the head of household was absent in 25% of houses approached. Interviewees were more likely to be women (68.7%), and the average age of interviewees was 41.1 years. The majority of respondents reported being self-employed small business owners (21.0%), informal recyclers (20.8%), or public employees in the municipal recycling plant (16.9%); the remainder held other salaried jobs (11.2%), completed manual labour (8.1%), or were otherwise employed (8.8%) or self-employed (13.4%).

Results

State discourses & strategies

Environmental health discourses and strategies always are political insofar as they reflect current social and political economic framings, ideals, and goals (e.g. Evered & Evered, Citation2012; Nading, Citation2014; Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996). For example, during the revolutionary Sandinista period (1979–1990), health education materials explicitly supported the popular revolution and encouraged loyalty to the FSLN party. The educational materials aimed to increase health literacy and provide citizens with scientific knowledge to address health concerns (Donahue, Citation1986). Further, revolutionary health materials incorporated reflection and discussion, intending to ‘empower people rather than control them from above’ (Donahue, Citation1986, p. 64).

In the contemporary period, the concept Buen Vivir first appeared in written state discourses in the National Human Development Plan for 2012–2016. In the 203-page document, Buen Vivir is neither defined explicitly nor discussed at length; in fact, it is mentioned only five times and Vivir Bien appears zero times. Nor is the term mentioned in the Model of Family and Community Health, the conceptual and planning framework for the Sandinista Ministry of Health, written in 2007 (MINSA, Citation2007). As in Ecuador and Bolivia, Nicaragua’s human development plan discusses ‘living well’ in the context of social and environmental processes: ‘the ongoing search of constructing the Living Well (Buen Vivir) for each Nicaraguan and the Common Good (Bien Común) among and for all Nicaraguan women and men as a whole, in harmony with Mother Earth (Madre Tierra)’ (PNDH, Citation2012, p. 14). Buen Vivir is briefly discussed in relation to both population health and environmental education. To the former, the ‘main health policy’ is ‘to accomplish that people do not become sick, a healthy pueblo is happy within the framework of Buen Vivir’ (PNDH, Citation2012, p. 84); to the latter, the state takes it upon itself to communicate to all Nicaraguans the importance of preserving and protecting Mother Earth. Finally, Article 98 of the Nicaraguan Constitution, amended in 2014, declares that Buen Vivir is the primary economic goal of the State:

The principal function of the State in terms of the economy is to achieve human sustainable development in the country; to improve the conditions of the pueblo and to achieve a more just distribution of wealth in the search of buen vivir.

In January 2013, First Lady Rosario Murillo invited all Nicaraguans to participate in the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign. The etho-politics orientation of the Basic Guide, the document written by the Nicaraguan government that outlines the campaign’s aims around fourteen themes, is diverse. According to Murillo, the campaign draws inspiration from ‘humanist, idealist, ethical, and evolutionary philosophies’ (Murillo, Citation2013). Further, Fisher notes that the campaign’s ‘language of “love,’ “care,” and “beauty,” (are) important elements in the FSLN’s re-visioned, 21st century political philosophy of sandinismo,’ a term used to connote the political ideology of early twentieth century Nicaraguan revolutionary fighter Augusto Sandino (Fisher, Citation2016). In the present day, critics suggest sandinismo represents a cultural as opposed to a political economic revolution (Kampwirth, Citation2008; Torres Rivas, Citation2007). At its core, contemporary sandinismo remains an appeal to the masses (el pueblo), as evidenced by its continued embrace of anti-imperialist rhetoric that characterised it in the 1970s and 1980s.

The origins of the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign are multifold. First, from a public health and urban planning perspective, the campaign responds to decades-long garbage mismanagement issues (e.g. lack of infrastructure, littering) in Nicaragua, particularly Managua and other urban areas (Nading & Fisher, Citation2017). Indeed, the country’s two largest periodicals – La Prensa and El Nuevo Diario – frequently highlight the country’s garbage woes and call attention to the connections among garbage mismanagement, public health concerns (e.g. mosquito-borne diseases and leptospirosis), and other crises such as flooding. Thus, the campaign’s focus on cleanliness is widely appealing to Nicaraguans (Envío Team, Citation2013). Second, the campaign seeks to galvanise support for the neighbourhood-level Cabinets of the Family, Community, and Life (CFCLs), which were announced in conjunction with the campaign and evolved out of the Citizen Power Councils (2007–2013), themselves a reincarnation of the Sandinista Defense Committees from the revolutionary period (Gertsch Romero, Citation2010; Potosme & Picón, Citation2013). Under Live Nice, Live Well, the barrio (neighbourhood) is the preferred ‘zone or space of governmental intervention’ (Osborne, Citation1997, p. 176). A major focus of CFCLs is to raise citizen ‘awareness’ (conciencia), and the campaign has been largely grounded in neighbourhood anti-littering campaigns and clean-ups. Third, from an economic perspective, the campaign expects that cleaning up Nicaragua will stimulate foreign investment and international tourism (El Citation19 Digital, Citation2013). Finally, the campaign solidifies Nicaragua’s sociocultural and political ties to other leftist Latin American countries – notably Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador – as mentioned above and as will be discussed further below.

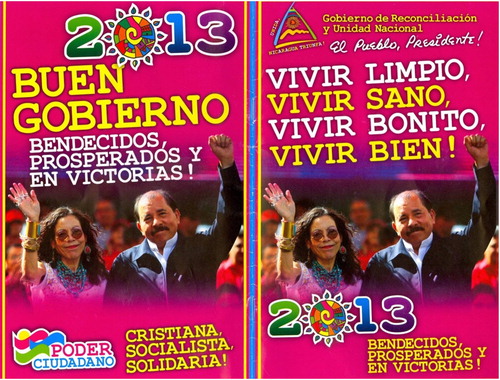

The campaign unites the Ministries of Health (MINSA), Environment and Natural Resources (MARENA), and Education (MINED), as well as the Nicaraguan Institute for Tourism (INTUR). Within weeks of its announcement, state institutions, along with volunteer members of CFCLs, distributed 500,000 copies of the Live Beautiful, Live Well Basic Guide () – in addition to ‘Yo Vivo Bonito’ (‘I Live Beautiful’) bumper stickers, posters, and other Live Beautiful, Live Well-themed propaganda – across Nicaragua, including in state-run schools (Envío Team, Citation2013). The CFCLs, other groups sympathetic to the FSLN party (e.g. Sandinista Youth), and state institutions led litter cleanups, educational workshops, and other activities to promote the national campaign. Further, the campaign received extensive attention in state-run media outlets and social media.

Figure 1. Front and back cover of the Live Beautiful, Live Well pamphlet distributed throughout Nicaragua by the national government in 2013.

Additionally, members of the FSLN party expect to rewrite Law 423, the General Health Law (Rugama, n.d.). It is plausible that the rewritten law will incorporate rhetoric from Live Nice, Live Well and the PNDH Citation2012–2016, thereby further linking Nicaraguan State discourses to indigeneity and the country’s unique blend of etho-politics.

The campaign, described as encompassing a set of ‘simple, easy, daily actions,’ covers fourteen wide-reaching topics around environmental stewardship, personal and collective health, and civic duties and state-civil society relations. Instead of recognising the heterogeneity of Nicaraguan citizens’ social, political, and ethnic identities, the Basic Guide homogenises them, preferring to use the singular in discussing ‘culture,’ ‘heritage,’ and ‘community identity.’ Despite the legal separation of state and Church per the Nicaraguan Constitution, it is not surprising that the Basic Guide references ‘Christian and family values’ given the Ortega administration’s alliance with the Catholic Church and the political currency of embracing Christianity in a country where citizens overwhelming identify as Christian.Footnote3 Live Beautiful, Live Well is not a juridical document and as such does not guarantee rights to human beings or nature as Buen Vivir does in the Ecuadorian constitution. Notably, neither Vivir Bien in Bolivia nor Buen Vivir in Ecuador tie ethical-moral values or rights to a specific religion.

In the following subsections, I examine specific themes of Live Beautiful, Live Well, including environmental health, pedagogy, the responsibilization of health and well-being, and indigeneity and environmental stewardship. Then, I examine lay perceptions of ‘live beautiful’ and ‘live well.’

Environmental health

In the contemporary period, Western public health discourses regularly reflect a broad understanding of the determinants of health, including social, psychological, and environmental elements (WHO, Citation2008). The same is true of the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign. The Basic Guide’s fourteen points reference health promotion and health education, nutrition, community participation, and hygiene, among others, as key factors contributing to individual and collective health and well-being. Commonly, modern public health campaigns conceptualise the physical environment as a biomedical risk or hazard to health and well-being (World Health Organization, Citation1989, p. 21). Live Beautiful, Live Well does this, too, though sparingly; for example, the risk posed by garbage to ‘natural, environmental, cultural, personal, familial, and community rights’ is the lone exception. Instead, the focus of the campaign – as evidenced by the Basic Guide and other state discourses – remains centred on altering the sociopolitical subjectivity of the Nicaragua population according to indigenous cosmovisions, as discussed below.

Pedagogy

The contemporary health discourses of the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign are distinct from those of the revolutionary period in that power is rigidly hierarchical. Power is unidirectional (top-down) and citizens do not collaborate with state entities in any meaningful manner; instead citizens – collectively or individually – alone are expected to meet the ‘fulfillment of … all the plans, campaigns, and norms related to health, healthy living spaces, citizen education, environmental restoration, cleanups, and beautification’ (Point 6). Consequently, such realities call into question the notion that post-neoliberalism signals the state’s intention to democratize governance and ‘make the state public’ (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012, p. 15). Whereas revolutionary health material encouraged discussion around a specific health issue or environmental health problem (e.g. preventing diarrhea, illnesses linked to inadequate garbage management), the focus of the Basic Guide is broad, and its utility for addressing specific environmental health risks is extremely limited. Moreover, the campaign does not itself represent a transfer of medical knowledge as did revolutionary health materials. Finally, in a departure from traditional leftist-led social medicine efforts in Latin America (Waitzkin, Iriart, Estrada, & Lamadrid, Citation2001) and prior Sandinista discourses, Live Beautiful, Live Well eschews attention to economic class differences; instead, it homogenises citizens. In sum, seemingly the campaign reflects hierarchical and populist underpinnings over a radical and revolutionary approach to environmental health governance.

Responsibilizing ‘Health’ and ‘Well-being’

Collective action is germane – or ought to be (Beaglehole, Bonita, Horton, Adams, & McKee, Citation2004; World Health Organization, Citation1978) – to definitions of ‘public health.’ During the revolutionary years (1979–1990), citizens assisted in the development, planning, and carrying out of ambitious social welfare projects in consultation with the state (e.g. neighbourhood-level Popular Health Councils and Popular Health Work Days) (Donahue, Citation1986). Collective and solidarity action was a fundamental organising principle of the revolutionary Ministry of Health, which stated ‘Health is a right of every individual and a responsibility of the State and the Popular organizations’ (Donahue, Citation1986, p. 25), and was institutionalised in the Constitution in 1987. In the contemporary period, Live Beautiful, Live Well strategically uses collective rhetoric to spur individual action to secure health and well-being to ‘promote the Beautiful and better Nicaragua that we all want’ (Point 9). To incite and promote collective action, Murillo uses the ‘we’ verb tense. Additionally, the Basic Guide uses key concepts like ‘unity’ to speak of Nicaraguan citizens as a collective whole and citizens are expected to work with State institutions, neighbourhood groups, and religious leaders to prevent certain social problems.

In the Basic Guide of Live Beautiful, Live Well, collective responsibility slips into individual responsibility for securing health and well-being. Live Beautiful, Live Well outlines several sets of specific duties, including keeping a tidy home, maintaining clean and beautiful neighbourhoods and public spaces, and caring for Mother Earth. The individual responsibilization exhibited by the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign exemplifies the notion that in the neoliberal present ‘the individual has never been more important’ as the individual citizen is germane to health governance and takes on an increasing number of responsibilities for their health and well-being (Brown & Baker, Citation2012, p. 1; Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996). Article 60 of Nicaragua’s Constitution from 1987 guaranteed the right to a healthy environment and declared that the State would ‘preserve, conserve, and rescue’ the physical environment. In contrast, the new version of the constitution, which was rewritten in 2014, proclaims that ‘Nicaraguans have a right to inhabit a healthy environment, (and) it is their obligation to preserve and conserve it’ (emphasis added). Thus, in devolving juridical responsibility to citizens, the recent amendment dropped entirely language obligating the State to preserve and conserve the environment, which ironically was amended to the Constitution in 1987 under President Daniel Ortega.

In addition, in Live Beautiful, Live Well, references to indigeneity overlap with and are entangled in solidarity principles, other humanistic values, and neoliberal values, producing a uniquely Nicaraguan set of discourses. For instance, Point 11 seeks to produce ‘good environmental citizens’ who recognise their duties and responsibilities in relation to consumer activities: ‘We promote the efficient use of water, energy and services that others still lack’ and ‘We promote a culture of simple living and without waste or ostentation, that hurts, excludes, or limits other citizens.’ As such, Point 11 recognises the need for solidarity in the face of market inequalities.

Indigeneity and environmental stewardship

Live Beautiful, Live Well departs from dominant public health discourses in its visible embrace of indigeneity and deep ecology. Here, ‘indigeneity’ is understood as the ‘social, cultural, economic, political, institutional, and epistemic processes through which the meaning of being indigenous in a particular time and place is constructed’ (Radcliffe, Citation2017). Indigenous knowledges often contrast with Western knowledges in that the latter are largely technocratic and science-oriented (Gregory, Johnston, Pratt, Watts, & Whatmore, Citation2009). Latin American indigenous conceptualizations of health, though numerous and diverse, often view individual life in harmony with community, the environment, and the universe (Montenegro & Stephens, Citation2006; WHO, Citation2007).

The Basic Guide of Live Beautiful, Live Well demonstrates the Nicaraguan State’s attempt to ‘speak like an indigenous State.’ Zimmerer developed this concept to describe the Bolivian State’s usage of indigenous grammars such as Living Well and Mother Earth, which he argues ‘[are] centred on widely common linguistic terms, rather than bureaucratic State-speak’ (Zimmerer, Citation2015, p. 315). Regarding Nicaragua, indigeneity is invoked on the cover of the Basic Guide booklet through the use of the serpent feather deity, Quetzalcoatl (). Since less than 9% of the national population identifies as indigenous (INIDE, Citation2005), the inclusion of the symbol, which also appears in a large memorial to the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez in the heart of Managua, is curious. Ettlinger and Hartmann (Citation2015) suggest the deployment of the symbol is intended to connect Nicaragua to pink tide Latin American governments, including Bolivia and Ecuador.

Second, Live Beautiful, Live Well uses the terms Mother Earth (Madre Tierra), Mother Nature (Madre Naturaleza), and Nature (Naturaleza). The Nicaraguan campaign uses these indigenous terms for nature differently than the term ‘environment’ (ambiente), which it uses in discussing environmental hazards and risks. The campaign uses the terms Mother Earth, Mother Nature, and Nature in stating that nature must be cared for and in discussing the relationship between human beings and the physical environment. To the latter, Live Beautiful, Live Well conceives of the individual body, families, and communities as interconnected and coexisting with Mother Earth.

Point 1: “We learn together … simple and practical norms of coexistence among us, between us and Mother Earth, and between family, community, public, and private spaces around cleanliness, hygiene, order, aesthetics, respect, loving care, and permanent solidarity.”

Point 10: “We learn to see in Nature and in natural environments, which we safeguard, as Gifts from God, temples of energy replacement, renewing our physical and spiritual strength and well-being in harmony and human comprehension.”

The inclusion of indigenous discourses in Live Beautiful, Live Well seems to be influenced by the Universal Declaration of the Common Good of the Earth and Humanity and the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia. To the latter, concepts of citizen coexistence and harmony with nature, which are discussed in Live Beautiful, Live Well, are of particular importance in the Bolivian (Article 403) and Ecuadorian constitutions (Article 275) (Gudynas, Citation2011a; Walsh, Citation2010). The similarities in indigenous grammars demonstrate the transnational and networked flows of (indigenous) cultures and rhetoric among leftist governments in Latin America (Andolina, Laurie, & Radcliffe, Citation2009).

Lay perceptions

To understand the ways in which government discourses align with and diverge from lay perceptions of ‘live beautiful’ (Vivir Bonito) and ‘live well’ (Vivir Bien), I asked heads of households in four communities in Managua to define each concept in their own words. As previous research elsewhere on views of health and well-being has found (Izquierdo, Citation2005; Richmond, Elliott, Matthews, & Elliott, Citation2005), it is not surprising that lay perceptions of ‘living beautiful’ and ‘living well’ varied widely.

Most definitions of ‘live beautiful’ fit into one of three categories: 1) cleanliness and the aesthetic environment, 2) social factors, and 3) economic factors (). First, many respondents equated ‘live beautiful’ with general cleanliness, tidiness, and orderliness (44.1%), as well as in the streets (27.3%) and in homes (25.2%) more specifically. For instance, a respondent, looking at her humble, government-provided home, stated:

If you clean the house, even if it isn’t a mansion, is to live beautiful, to live clean and orderly. (Woman, 40 years old)

Table 1. Lay perceptions of definitions of Live Beautiful (Vivir Bonito).

Second, many community members linked social features, such as getting along with neighbours (25.9%) – sometimes discussed as living in harmony with their community – as well as collective participation and solidarity (5.6%), to ‘living beautiful.’ Being in good health and having health (20.3%), which were nearly always discussed in relationship to cleanliness, were key to being able to ‘live beautiful.’ For example, a 42-year-old woman who was relocated by the government from a flood-prone squatter settlement to new government housing shared:

Live tidy. If … you don’t live like a pig and if we clean our house there won’t be any illnesses. Flies come … and then you get vomiting.

Definitions of ‘live well’ () differed from live beautiful in that descriptions largely revolved around economic and social factors. For example, respondents most frequently equated having a decent job, salaried position, or improved economic condition (29.4%) with living well. Moreover, several respondents defined living well as the ability to eat everyday (23.1%), meet their basic needs (e.g. afford housing and food) (18.2%), or live in a decent house (16.8%). For example, two men who previously worked informally in the garbage dump and secured salaried positions in the new municipal recycling plant shared similar sentiments:

(To live well) is to not lack anything. At times, I don’t live well because I lack food … I only eat beans.” (Man, 54 years old)

It is not only living beautiful (and) we would live not only rich, but be able to provide for us and other children.” (Man, 63 years old)

Table 2. Lay perceptions of definitions of Live Well (Vivir Bien).

Respondents also equated ‘living well’ with being in good health and having health (23.1%). In this context, however, healthiness was not tied to cleanliness like it was for ‘living beautiful’; rather, to ‘live well’ was described as a general state of well-being dependent on economic factors and social relations. Respondents believed getting along and living in harmony with neighbours (19.6%) and family (7.0%) as well as the ability to live in peace (e.g. tranquility, without fear of gangs or crime) (11.9%) to be key components of ‘living well.’

It is notable that respondents were less likely to offer definitions for ‘live well’ (9.8%) than ‘live beautiful’ (4.9%); relatedly, several respondents described ‘live well’ as ‘a huge word’ and ‘a very broad word’ and, thus, difficult to define. Further, some participants equated ‘live well’ with ‘live beautiful,’ suggesting that there was not a difference between the two terms (7.7%). Finally, ‘live well’ was less likely than ‘live beautiful,’ albeit it slightly, to be linked to solidarity and community participation (4.2% vs. 5.6%) and environmental stewardship (2.8% to 6.3%).

Respondents had mixed feelings when asked whether they thought that they could ‘live beautiful’ and ‘live well’ in their neighbourhood. Most agreed that it was possible, but believed it depended on an individual person’s demeanour and behaviours:

Depends on the people themselves. (Woman, 18 years old)

If one wants to, yes. If one doesn’t want to, then no. (Man, 26 years old)

Moreover, many respondents stated that the solution to improving the quality of life among households and in the community was to make people aware of (concientizar) and change personal behaviours instead of addressing contextual, sometimes systemic factors.

In contrast, other respondents spoke about the importance of shared collective responsibility:

Yes (I can live beautiful and live well) because of neighborhood solidarity. There are many compañeros. There is good communication among people. We support each other; not only Sandinistas. (Woman, 33 years old)

Some—not all—participate in clean-ups of public areas and streets. We have to get people involved, meet with them regularly. (Woman, 31 years old)

In referencing neighbourhood solidarity, these responses echo Sandinista discourses of the revolutionary and contemporary periods.

Still other respondents tied health and well-being to structural processes not discussed in the Basic Guide of Live Beautiful, Live Well. Participants indicated that their ability to ‘live beautiful’ and to ‘live well’ was determined by political economic issues out of their control. Specifically, many participants referenced their lack of employment or underemployment and its impact on their ability to ‘live well’:

Yes, but we have to have a good job. Yes, here we live beautiful, but we do not live well. (Woman, 34 years old, 3 members of her 9-person household work in informal recycling economy)

There has to be a wage that conforms to the basic food basket, (if not) we can’t live well.

In summary, the data yield several noteworthy patterns. Survey responses are similar to the Nicaraguan state’s key discourses about ‘live beautiful,’ as reflected by each mentioning cleanliness, tidiness, and living in social harmony with neighbours and families. Also, lay perspectives rarely associate environmental stewardship with conceptualizations of ‘live beautiful’ and ‘live well.’ Finally, several principal concerns that Nicaraguan citizens expressed – employment, income, meeting basic needs – are not discussed at all in the Basic Guide of Live Beautiful, Live Well, evidence of a potential disconnect between this national campaign and on-the-ground realities of everyday life in Nicaragua.

Discussion and conclusion

The Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign aspires to a reformulated environmental health governance model to change the ‘culture of everyday life’(Murillo, Citation2013) in Nicaragua. As a governmental technique (Ghertner, Citation2010), the campaign appeals to the masses with its focus on urban aesthetics (i.e. urban hygiene) while simultaneously instilling much broader socio-political and environmental expectations of a unique subjectivity, what I term ‘post-neoliberal citizenship.’ ‘Post-neoliberal citizenship’ demonstrates the complex and not-quite-neoliberal forms of idealised citizenship envisioned by the Nicaraguan state, or rather President Daniel Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo. Moreover, at a time when questions have arisen elsewhere in Latin America regarding the point of emergence of the concepts Vivir Bien and Buen Vivir (Hidalgo-Capitán, Arias, & Ávila, Citation2014), this study provides some evidence that Vivir Bien and Vivir Bonito, at least as framed by the Nicaraguan state, may be best understood as an ‘invention’ by those in power rather than the product of social movements from below.

In comparison to campaigns from the revolutionary period, Live Beautiful, Live Well highlights several changes to how environmental public health is conceptualised and practiced. First, key determinants of health are absent in Live Beautiful, Live Well, and its utility as an environmental health campaign, outside of encouraging citizens to tidy up their homes, is questionable. Specifically, critics point out that Live Beautiful, Live Well ‘disguises,’ or covers up, economic realities of Nicaragua’s poor majorities (Potosme & Picón, Citation2013). Similarly, one survey participant, stated ‘only in Rosario (Murillo)’s illusion and mind do people live beautiful because there are people that don’t eat.’ Second, the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign is not, nor does it strive to be, liberating and empowering as was the objective of popular health education pedagogy of the revolutionary era. Neither does the campaign celebrate nor recognise the plurality of Nicaraguan citizenship, as guaranteed in the constitution. Instead, the campaign represents a set of top-down discourses aimed at normalising society (Foucault, Citation1980a) through a particular ‘regime of truth’ (Foucault, Citation1980b, p. 131). State discourses demand citizens adopt a particular set of normative etho-politics (Rose, Citation1999) focused on indigenous grammars and logics around nature-society relations applied to health and well-being. Taken as a whole, the Basic Guide of Live Beautiful, Live Well falls into a similar normalising trap as Buen Vivir / Sumak Kawsay in Ecuador: ‘it unthinkingly reproduces a form of elite post-colonial modernity that continuously denigrates other ways of knowing and practicing development’ (Radcliffe, Citation2012, p. 247).

This study examined whether state discourses around social, health, and environmental matters match perceptions of citizens living in communities targeted by the campaign. Notably, not one of the 146 surveyed participants spoke of the indigenous grammars discussed in the campaign. The results are not unexpected: incorporating indigeneity in everyday governmentalities may seem out of place in Nicaragua, since less than 9% of Nicaraguans identify as indigenousFootnote4 (INIDE, Citation2005). References to indigeneity extend the perception that the Ortega administration is sensitive to inclusivity of diverse cultures and may assist in redirecting attention away from Nicaragua’s continued involvement in environmentally destructive and neoliberal development projects (e.g. mining concessions, the proposed interoceanic canal), which negatively affect local populations, indigenous and non-indigenous alike (Hartmann, Citation2013). At the regional scale, sensitivity to indigeneity buys Nicaragua socio-political currency with other Latin American nations, notably Ecuador and Bolivia, where indigenous groups compose much larger percentages of national populations (Ettlinger & Hartmann, Citation2015; Gudynas, Citation2011a; Radcliffe, Citation2017; Walsh, Citation2010; Zimmerer, Citation2015).

Also, Live Beautiful, Live Well propagates notions of individual responsibility for health, a hallmark of neoliberal health governance in Latin America and globally. In Nicaragua, citizen participation is key for securing health and well-being in the contemporary period. Under the discourses of solidarity, individual citizens are made responsible for their health and well-being as well as that of their families, communities, and Mother Nature (Envío Team, Citation2013). Furthermore, citizens are expected to care for public and private spaces alike – while the role of the state is neither questioned nor discussed at any significant length – in the name of solidarity and shared responsibility. On one hand, participants’ responses reflect revolutionary and contemporary Sandinista discourses that stated change begins at the household and street level (Donahue, Citation1986). On the other hand, reducing issues of health and well-being to personal (i.e. individualised) responsibility call to mind neoliberal rhetoric (Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996) that the Ortega administration often speaks against. Indeed, Dora Maria Tellez, former Minister of Health during the revolutionary period and historian, expressed concern that the campaign’s slogan seems to be ‘Don’t ask me to solve your problems, change your attitude’ (del Cid, Citation2013). Such mentalities, which permeated Nicaraguan society from 1990 to 2006, failed to take into consideration other contributing factors such as social, economic, and political determinants of health. Thus, the data demonstrate the difficulty in determining the origin(s) and entanglement of diverse governmentalities concerning environmental health citizenship. In sum, new duties and ways of thinking, which are expressed in the Basic Guide of Live Beautiful, Live Well, through state propaganda, and by members of neighbourhood-level CFCLs, communicate the expectations of ‘post-neoliberal citizenship’ to Nicaraguans.

In contemporary Nicaragua, post-neoliberal citizenship demands by the state demonstrate the tensions and contradictions between neoliberalism, socialism, and post-neoliberalism. On one hand, state discourses are centred around socialist notions of ‘solidarity’ and ‘shared responsibility.’ This matches the definition of liberal citizenship in the first half of the twentieth century: ‘a social being whose powers and obligations were articulated in the language of social responsibilities and collective responsibilities’ (Miller & Rose, Citation1993, p. 97). In the case of Nicaragua – as well as Ecuador and Bolivia – social/collective responsibility is paired with post-neoliberal indigenous grammars depicting harmonious nature-society relations whereby citizens are made responsible for the care of Mother Earth. Amidst liberal and post-neoliberal duties, the latter overlaps with neoliberal expectations of citizenship, too. Live Beautiful, Live Well discusses environmental duties such as water and energy conservation in relation to the market economy (and social solidarity), thereby exemplifying neoliberal rationalities (Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996). Thus, in being made responsible for individual health and well-being as well as that of their neighbours and community, ‘citizenship is (understood) to be active and individualistic rather than passive and dependent’ (Miller & Rose, Citation1993, p. 98). Survey data, too, indicate that consideration of social responsibilities, to which CFCL members in particular ascribe, is largely overshadowed by notions of individual responsibilization for personal health. While contemporary governance in Nicaragua seemingly grants citizens freedom and autonomy in a manner characteristic of neoliberal governmentalities (Miller & Rose, Citation1993; Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996), the state’s normative ethos-politics simultaneously seeks to inculcate various post-neoliberal moral and political values, including solidarity, socialism, environmental stewardship, and indigeneity.

In conclusion, contemporary environmental health governance in Nicaragua, as examined through the lens of the Live Beautiful, Live Well national campaign, is entangled in specific normative socio-political agendas, representing an amalgam of diverse socio-political orientations. Under the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign, health and well-being – both broadly defined – come under the purview of the modern state, which attempts to shape the habits, aspirations, and beliefs of citizens toward particular post-neoliberal goals. In doing so, the campaign – and the state more broadly – seeks to produce a normalised post-neoliberal citizenry that reflects the diverse antecedents of contemporary governance in Nicaragua and Latin America. Finally, the Live Beautiful, Live Well campaign demonstrates the diversity of conceptualizations of health, wellbeing, and citizenship in contemporary and post-neoliberal Latin America.

Acknowledgements

Becky Mansfield, Kendra McSweeney, Nancy Ettlinger, and Jennifer Hartmann provided valuable feedback on this research. This research was made possible with the financial support from Ohio State University, Tinker Foundation, and Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Chris Hartmann http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8947-205X

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The state and popular media outlets commonly refer to the campaign using the shorthand Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien. ‘Bonito’ may be translated as ‘pretty,’ ‘beautiful,’ or ‘nice.’

2. Still other academics consider recent changes as representing the rise of a socially conscious and aware variant of neoliberalism—labeled as ‘inclusive neoliberalism,’(Craig & Porter, Citation2003) ‘social neoliberalism,’(Andolina et al., Citation2009, p. 8) or ‘adjustment with a human face’(Radcliffe, Laurie, & Andolina, Citation2004, p. 398).

3. In fact, Vice-President Murillo stated that she was ‘very proud’ that Nicaragua ‘is the only country in the world that declares itself Christian’ (Envío Team, Citation2013).

4. In contrast, more than 70% of Bolivians identify as indigenous; thus, invoking indigeneity-laden grammars is a way to consolidate the political and moral support of the masses (Zimmerer, Citation2015).

References

- Andolina, R., Laurie, N., & Radcliffe, S. (2009). Indigenous development in the Andes: Culture, power, and transnationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Beaglehole, R., Bonita, R., Horton, R., Adams, O., & McKee, M. (2004). Public health in the new era: Improving health through collective action. The Lancet, 363(9426), 2084–2086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16461-1

- Bebbington, A., & Humphreys Bebbington, D. (2011). An Andean avatar: Post-neoliberal and neoliberal strategies for securing the unobtainable. New Political Economy, 16(1), 131–145. doi: 10.1080/13563461003789803

- Brown, B., & Baker, S. (2012). Responsible citizens: Individuals, health, and policy under neoliberalism. London: Anthem Press.

- Constitución de Bolivia. (2009). Ministerio de la Presidencia, Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. 178 pp.

- Constitución del Ecuador. (2008). Asamblea Constituyente. 218 pp.

- Craig, D., & Porter, D. (2003). Poverty reduction strategy papers: A new convergence. World Development, 31(1), 53–69. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00147-X

- del Cid, A. (2013, February 11). Batalla digital “vivir bonito.” La Prensa. Retrieved from http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2013/02/11/nacionales/134201-batalla-digital-vivir-bonito.

- Donahue, J. (1986). The Nicaraguan revolution in health: From Somoza to the Sandinistas. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, Inc.

- El 19 Digital. (2013, February 5). Companera Rosario invita a familias nicaraguenses a enfrentar juntos el desafio de vivir en una Nicaragua mejor (Companera Rosario invites Nicaraguan families to confront together the challenge to live in a better Nicaragua). Retrieved from http://www.elpueblopresidente.com/EL-19/15136.html.

- Envío Team. (2013). Is it a bird? A plane? A cultural revolution … ? Revista Envío, (379).

- Escobar, A. (2010). Latin America at a crossroads: Alternative modernizations, post-liberalism, or post-development? Cultural Studies, 24(1), 1–65. doi: 10.1080/09502380903424208

- Ettlinger, N., & Hartmann, C. D. (2015). Post/neo/liberalism in relational perspective. Political Geography, 48, 37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.05.009

- Evered, K. T., & Evered, EÖ. (2012). State, peasant, mosquito: The biopolitics of public health education and malaria in early republican Turkey. Political Geography, 31(5), 311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.05.002

- Fisher, J. (2016). Cleaning up the streets, Sandinista-style: The aesthetics of garbage and the urban political ecology of tourism development in Nicaragua. In M. Mostafanezhad, R. Norum, E. J. Shelton, & A. Thompson-Carr (Eds.), Political ecology of tourism: Community, power and the environment (pp. 231–250). London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (1980a). Two lectures. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977 (pp. 78–108). New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. (1980b). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977 (pp. 109–133). New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. (2000). Governmentality. In J. Faubion (Ed.), Michel foucault, power (pp. 201–222). New York: The New Press.

- Foucault, M. (2003). 17 march 1976. In “Society Must be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France 1975-1976 (pp. 239–264). New York: Picador.

- Gertsch Romero, E. (2010, May 16). De los CDS a los CPC (From the CDS to the CPC). La Prensa. Retrieved from http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2010/05/16/politica/24768-de-los-cds-a-los-cpc.

- Ghertner, A. (2010). Calculating without numbers: Aesthetic governmentality in Delhi’s slums. Economy and Society, 39(2), 185–217. doi: 10.1080/03085141003620147

- Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M., & Whatmore, S. (eds.). (2009). The dictionary of human geography (5th ed). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Grugel, J., & Riggirozzi, P. (2009). Conclusion: Governance after neoliberalism. In Governance after neoliberalism in Latin America (pp. 217–230). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grugel, J., & Riggirozzi, P. (2012). Post-neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and reclaiming the state after crisis. Development and Change, 43(1), 1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01746.x

- Gudynas, E. (2011a). Buen vivir: Germinando alternativas al desarrollo. América Latina En Movimiento, 462, 1–20.

- Gudynas, E. (2011b). Buen vivir: Today’s tomorrow. Development, 54(4), 441–447. doi: 10.1057/dev.2011.86

- Guerrero. (2015, October 7). Nicaragua es menos pobre, asegura BCN. El Nuevo Diario. Retrieved from http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/372748-nicaragua-reduce-pobreza-aumenta-consumo/.

- Hartmann, C. (2016). Postneoliberal public health care reforms: Neoliberalism, social medicine, and persistent health inequalities in Latin America. American Journal of Public Health, 106(12), 2145–2151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303470

- Hartmann, C. (2018). Waste picker livelihoods and inclusive neoliberal municipal solid waste management policies: The case of the La Chureca garbage dump site in Managua, Nicaragua. Waste Management, 71, 565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.10.008

- Hartmann, C. D. (2013). Garbage, health, and well-being in Managua. NACLA Report on the Americas, 46(4), 62–65. doi: 10.1080/10714839.2013.11721896

- Harvey, D. (2006). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Hidalgo-Capitán, A. L., Arias, A., & Ávila, J. (2014). El pensamiento indigenista ecuatoriano sobre el Sumak Kawsay [Ecuadorian indigenist thought about Sumak Kawsay]. In A. L. Hidalgo-Capitán, A. Guillén García, & N. Deleg Guazha (Eds.), Antología del Pensamiento Indigenista Ecuatoriano sobre Sumak Kawsay (pp. 29–73). Huelva y Cuenca: FIUCUHU.

- Homedes, N., & Ugalde, A. (2005). Why neoliberal health reforms have failed in Latin America. Health Policy, 71(1), 83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.01.011

- INIDE. (2005). Censo de población (Population census). Inistituto Nacional de Información de Desarrollo. Retrieved from http://www.inide.gob.ni/censos2005/resumencensal/resumen2.pdf.

- INIDE. (2015). Results of the national households survey on measurement of level of life, 2014. Instituto Nacional de Informacion de Desarrollo. Retrieved from http://www.inide.gob.ni/Emnv/Emnv14/Poverty%20Results%202014.pdf.

- ISAGS. (2012). Sistemas de salud en suramerica: desafíos para la universalidad, la integralidad y la equidad. Instituto Suramericano de Gobierno en Salud.

- Izquierdo, C. (2005). When “health” is not enough: Societal, individual and biomedical assessments of well-being among the Matsigenka of the Peruvian Amazon. Social Science & Medicine, 61(4), 767–783. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.045

- Kampwirth, K. (2008). Abortion, antifeminism, and the return of Daniel Ortega: In Nicaragua, Leftist Politics? Latin American Perspectives, 35(6), 122–136. doi: 10.1177/0094582X08326020

- Kennemore, A., & Weeks, G. (2011). Twenty-First century socialism? The elusive search for a post-neoliberal development model in Bolivia and Ecuador. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 30(3), 267–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9856.2010.00496.x

- Macdonald, L., & Ruckert, A. (2009). Post-neoliberalism in the Americas: An introduction. New York: Palgrave.

- Miller, P., & Rose, N. (1993). Governing economic life. In M. Gane, & T. Johnson (Eds.), Foucault’s New Domains (pp. 75–105). London: Routledge.

- MINSA. (2007). Modelo de Salud Familiar y Comunitario [Model of family and community health]. Nicaragua: Ministerio de Salud (Ministry of Health).

- Montenegro, R. A., & Stephens, C. (2006). Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Lancet, 367(9525), 1859–1869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68808-9

- Muhr, T. (2013). Counter-globalization and socialism in the 21st century: the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America. London: Routledge.

- Murillo, R. (2013, January 25). Estrategia Nacional para “Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien … !” [National strategy to “live clean, live health, live nice, live well … !”]. Retrieved from http://www.el19digital.com/articulos/ver/titulo:7428-estrategia-nacional-para-vivir-limpio-vivir-sano-vivir-bonito-vivir-bien.

- Nading, A. (2014). Mosquito trails: Ecology, health, and the politics of entanglement. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Nading, A., & Fisher, J. (2017). Zopilotes, Alacranes, y Hormigas (Vultures, Scorpions, and Ants): animal metaphors as organizational politics in a Nicaraguan garbage crisis. Antipode. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/anti.12376

- Osborne, T. (1997). Of health and statecraft. In A. Petersen, & R. Bunton (Eds.), Foucault, health, and medicine (pp. 173–188). London: Routledge.

- Petersen, A., & Lupton, D. (1996). The new public health: Health and self in the age of risk. London: SAGE Publications.

- PNDH. (2012). Plan nacional de desarrollo humano: 2012-2016 [National human development plan: 2012-2016]. Managua: Government of Nicaragua.

- Potosme, R., & Picón, G. (2013, February 8). Ven fascismo en doctrina de Murillo. La Prensa. Retrieved from http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2013/02/08/politica/133883-ven-fascismo-en-doctrina-de-murillo.

- Radcliffe, S. A. (2012). Development for a postneoliberal era? Sumak kawsay, living well and the limits to decolonisation in Ecuador. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 43(2), 240–249.

- Radcliffe, S. A. (2017). Geography and indigeneity I: Indigeneity, coloniality and knowledge. Progress in Human Geography, 41(2), 220–229. doi: 10.1177/0309132515612952

- Radcliffe, S. A., Laurie, N., & Andolina, R. (2004). The transnationalization of gender and reimagining andean indigenous development. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 29(2), 387–416. doi: 10.1086/378108

- Richmond, C., Elliott, S. J., Matthews, R., & Elliott, B. (2005). The political ecology of health: Perceptions of environment, economy, health and well-being among ‘Namgis First Nation. Health & Place, 11(4), 349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.04.003

- Rose, N. (1996). Governing “advanced” liberal democracies. In Foucault and political reason: Liberalism, neo-liberalism and rationalities of government (pp. 37–64). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rose, N. (1999). Inventiveness in politics. Economy and Society, 28(3), 467–493. doi: 10.1080/03085149900000014

- Rugama, H. M. (n.d.). Priorizarán reforma a Ley General de Salud en 2016 [They will prioritize a reform to the General Health Law in 2016]. El Nuevo Diario. Retrieved from http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/politica/380400-priorizaran-reforma-ley-general-salud-2016/.

- Sader, E. (2009). Post-neoliberalism in Latin America. Development Dialogue, 51, 171–179.

- Torres Rivas, E. (2007). El retorno del sandinismo transfigurado [The return of transfigured sandinismo]. Nueva Sociedad: Democracia Y Política En América Latina. Retrieved from http://nuso.org/articulo/el-retorno-del-sandinismo-transfigurado/.

- Waitzkin, H., Iriart, C., Estrada, A., & Lamadrid, S. (2001). Social medicine then and now: Lessons from Latin America. American Journal of Public Health, 91(10), 1592–1601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1592

- Walsh, C. (2010). Development as Buen Vivir: Institutional arrangements and (de)colonial entanglements. Development, 53(1), 15–21. doi:10.1057/dev.2009.93.

- WHO. (2007). Health of indigenous peoples. United Nations World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs326/en/.

- WHO. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on social determinants of health final report. Geneva: World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health.

- World Health Organization. (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR.

- World Health Organization. (1989). Environment and health: The European charter and commentary. Frankfurt-am-Main: WHO Regional Publications.

- Zimmerer, K. S. (2015). Environmental governance through “speaking like an indigenous state” and respatializing resources: Ethical livelihood concepts in Bolivia as versatility or verisimilitude? Geoforum, 64, 314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.07.004