ABSTRACT

Diabetes has become a leading cause of death in Belize, making this Central American country emblematic of challenges amplified by a growing global diabetes epidemic. The struggles people face as they seek care for chronic conditions like diabetes (and its complications such as kidney failure) are bringing citizens and institutions alike to revisit longstanding norms about the terms through which healthcare is accessed. Ethnographically tracing Belize’s first patient-driven healthcare protests and activism – an ad hoc movement for public dialysis that began over a decade ago – this paper examines patients’ and caregivers’ struggles to probe and shape a legacy of social justice health activism, drawing on perspectives from an often-overlooked part of Central America where basic healthcare access has not historically been framed as a right of citizens. It considers these dilemmas in relation to much larger chronic struggles ‘to maintain’ and repair bodies, medical technologies, and health systems in the aftermath of colonial legacies – with special attention to the challenges posed for small countries now facing rising issues of diabetes injuries and chronic complications – and the role of civic media and citizen activism in this context.

A global epidemic as seen from Belize

‘We have a list of people waiting,’ the nurse at the Belize City dialysis centre told me when I arrived in September 2010. ‘Here, you will only meet the lucky ones.’

Most of the people I met with end-stage kidney disease during a year of chronicling diabetes experiences in Belize had been spread out, but in the dialysis centre they sat chair after chair. Many of them were restless during the hours-long treatment and full of things they wanted to say into my tape recorder: whether or not they received partial state support for this session; the ways they earned money to take the bus here; whatever they knew about the person whose death it was that opened a spot for them this room. I recognised some of their faces and names from news stories about the recent protests, including a Kriol woman who waved me over. She introduced herself as Ms. C and asked me to use a version of this name as the Belizean newspapers had; she was strategically trying to turn herself into a public figure. With changes on the horizon in partial response to their media work, the room’s group of patients were learning to leverage the stories of their plights in new ways. ‘Share the story when you go home. Diabetes,’ Ms. C said. If it wasn’t for the dialysis, she added, ‘I would have died already.’

I had the sense of stepping straight into the news cycle stories that brought me to that room:

[Ms. C] … told our newspaper that February 2009 will mark one year since she has been taking dialysis treatments. She, too, is concerned about the lack of a doctor at the dialysis unit.

‘I know that it’s hard, because we don’t have a doctor. When our pressure goes up, God is the doctor. When my pressure goes up high I pray God please help me and I beg him because I don’t have any money for any doctor,’ [she] shared … .

Fighting back her tears, C. complains of having an extremely difficult time even affording the transportation expenses to get to Belize City for dialysis treatments three times a week (Ramos, Citation2009, p. 1; Citation7 News Belize, Citation2009, December Citation30).

It felt intense to enter a space where people regarded storytelling with this sense of potential existential stakes. On a Monday morning, after visiting the week before, I heard the news alongside the room of patients that one of the country’s 21 dialysis patients had died over the weekend. Someone waiting would be bumped up the list kept on a paper taped to the desk near the phone, a list which easily fit on one page. A new regular would be sitting in his chair by Wednesday. ‘I was just talking with him on Friday,’ reflected one man getting dialysis. ‘You can be walking today and by tomorrow morning you are … not here.’ The unit’s patients on once-weekly treatment were dying so quickly that it created a palpable sense that everyone was sitting in someone else’s former place, and that someone new would occupy their blue chair once they were gone.

I felt myself being immediately enrolled into some much more fortunate transient rotation, one in a long line of past and future storyteller-witnesses visiting that room. At times I stopped writing in my notebook because I was listening so intently that I knew each word would be imprinted on my mind later anyway. Other times I would stop writing for the opposite reason, because bodily I just could not take in any more. Both limits left me feeling dizzy and spilling over. It was at times a physical relief to have a tape recorder rolling on those days, to think it would be possible to process later whatever could not be absorbed in real time. But later I found the tapes almost unbearable to listen to – piercing machines, background televisions, and bits of hardship coming from all sides that I found no way to pass along on a relevant interval. Many of those who were sitting in one of those chairs that day died many years ago. Others have survived against all odds.

For all the hardship assembled in one room, the stories of those waiting were also on my mind, people I’d spoken with in hospitals across the country. Some of them make the exhausting journey by school buses to Mexico for dialysis three times a week in hopes that something might change, or waited hoping for a phone call.

This was the broader backdrop when I met Jose Cruz in Belize City. By that time, he had already reached a certain level of national celebrity, after initiating the first rights-based patient activism movement in the history of Belizean national medicine. Together with his wife Mileni and a group of patients and their families from the Kidney Association of Belize, and joined by caregivers, their collective organised civic protests and eventually gathered support among the government for partnering with a U.S.-based NGO to build the country’s first public dialysis centre. Since Belize does not have a constitutional right to health, Cruz’s actions were not played out on judicial fronts, but rather through the national media that covered his activism. He began organising media conferences and issuing press releases about each part of his body that got amputated within a health system unable to support patients like him (). For a time, he boycotted his own dialysis treatment until the government took steps to offer the same to other patients on the waiting list. As Cruz put it in a 2009 media interview (7 News Belize, Citation2009, July 1):

I am willing to stop doing my dialysis. I am willing to die for it …

This is nonsense. People are dying for God’s sake … We have people dying, literally dying and nobody’s paying attention. So I am making a stand today.

Figure 1. Jose Cruz holding an amputation press release (Photo Courtesy of Channel 5 Belize News. Used with permission).

Figure 2. One of Kolff’s kidney dialysis machine prototypes, made from an apricot can. (Science & Society Picture Library / Getty Images)

The first working dialysis machine was cobbled out of sausage casings, juice cans, and a clothes washing machine during the shortages of wartime, when Dutch physician Willem Kolff’s tinkering with his vision of the world’s first artificial organ in 1941 transformed the history of medicine. He never patented the invention (), hoping that keeping the technology open-access would make future machines more accessible to others (Blakeslee, Citation2009, p. 1). In the U.S., dialysis and kidney transplants have been legally provided by the national government since 1972 (Rettig, Citation2011). It took more than half a century for such devices to reach Belize, when in 2003 Guatemalan kidney specialist Dr. Miguel Rosado opened the first dialysis unit at a private hospital in Belize City. After Dr. Rosado died tragically three years later in a car accident in Belize, his dialysis centre remained intact but was missing its founder’s propelling vision (Belize News, Citation2003; 7 News Belize, Citation2009 July). This made for a difficult reality, because the skyrocketing diabetes rates across Central America have left an increasing number of patients in kidney failure and in need of dialysis in order to survive. But after Rosado’s death, there was no nephrologist or endocrinologist working in Belize, and no public dialysis unit in the country. By the time I began this project in 2009, dialysis sessions in the private hospital were exorbitantly expensive (costing $680 a week), and any participating patients had to sign a waiver acknowledging that they wanted to accept the risks of getting dialysis even though there was usually no doctor present.

In investigating how patients and physicians alike are navigating such gaps in state infrastructures, I join scholars who return to James Scott’s notion of ‘infrapolitics’ (Citation1990) from a somewhat different angle and era of global politics, focusing on moments where a public’s ordinary actions bear out in ways that at times unexpectedly intersect with – and may even expand or guide – directions of state development (Appel, Anand, & Gupta, Citation2015). This kind of ethnographic emphasis in turn ‘compels us to think of people not as problems or victims, but as agents of health’ (Biehl & Petryna, Citation2013, p. 11; see Hatch Citation2016; Hoover Citation2017; Montoya, Citation2013; Roberts Citation2017; Solomon, Citation2016; Yates-Doerr, Citation2015).

‘This is the first time in [Belizean] history we have a group of actual patients suffering from an ailment come together and demanding what they want,’ Cruz told one national news station. ‘I hope that the Belizean people are taking notice.’

Inventing a right to health

Belize’s first patient-driven healthcare protests and activism – a movement for public dialysis – thus began unfolding in 2009, over a decade ago. This article describes patients’ and caregivers’ struggles to probe and shape a legacy of social justice health activism, drawing on perspectives from an often-overlooked part of Latin America where basic healthcare access has not historically been framed as a right of citizens. In a country long marked by patchwork infrastructures, Belize’s diverse national population – speaking languages including Kriol, English, Spanish, Garifuna, Maya (Mopan, Yucatec, and Kekchi), and Chinese – is experimenting across registers with fragile forms of collective organising. By thinking about healthcare movements in Latin America in relation to a country frequently dismissed as marginal, this case from Belize invites comparative inquiry about the implications of particular colonial legacies for contemporary citizenship claims, as well as for reconsidering how labels like ‘Caribbean’ or ‘Latin America’ are defined and enacted in the first place (Wilk, Citation2006).

A few notes on regional background may be helpful as historical context for the exchanges that follow. While people often remark that Belize is ‘both Latin American and Caribbean,’ Michael Stone (Citation1994) has noted that scholarship frequently tends to treat it as neither, often falling between the cracks of both regions’ historiographies. But to call Belize an ‘exception’ in Latin America forces us to consider how we are defining the region’s norms. The country has been called many things over the years: a ‘colonial dead end’ (Clegern, Citation1967); ‘a meeting place for the strands of history’ (Grant, Citation1976, pp. ix–xi); a ‘strange little fragment of empire’ (Huxley, Citation1934). In all, Belize spent over two centuries as a squatter community of uncertain status – settled by unauthorised British rogues on Spanish-owned land, yet under the consolidated control of neither England nor Spain and largely inventing their own laws – before the Settlement finally became recognised as British land in 1850. This means that Belize did not even become a European colony until the countries surrounding (Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras) had already won their independence from Spain and became sovereign nations. Belize thus spent much more time in this liminal phase of its existence (230 years) than it did as an officially recognised British territory (21 years), a Crown colony actually being governed by England (110 years), or as an independent nation ruled by constitutional monarchy (with an elected Belizean Prime Minister and the official head of state remaining the Queen of England) from 1981 until the present (Bolland, Citation1977). The former British Honduras arranged for its colonial rulers to stay two extra decades due to threat of war from Guatemala. (Even today, a very common Guatemalan saying – based on an old colonial land dispute – claims that Belice es nuestro (Belize is ours), while the Kriol language counter-slogan holds instead that Da Fu Wi Belize (‘This is Our Belize’) reflecting tensions finally sent to the International Court of Justice in 2019). Yet even early in its origins, the people who lived in Belize wrote of ‘their country,’ although the place was part of no nation’s empire. When Clifford Geertz spoke of the ‘central interpretative issues’ raised by the ‘uncenteredness of modern times,’ he hit on a question that Belize has wrestled with continuously from its earliest history: ‘What is a Country if It Is Not [Only] a Nation?’ (Geertz, Citation2000, p. 228)

Belizeans have not had a constitutional right to health in the history of their nation, nor a patient activist group that had come together to leverage a particular policy demand from the state. People I spoke with seemed generally unsure what to expect from their country, in terms of health or institutional care. The public health system relies largely on rotating physicians, especially from Cuba. The expectations and norms I encountered in the national system shaped by these histories proved quite different, for example, from what Sherine Hamdy has described in her work with dialysis and transplant patients in Egypt, where people expressed an idea that both their state and their kidneys had failed (Hamdy, Citation2008). Yet such charges and protests in the Egyptian case that Hamdy observed also animated future demands, and spoke of a responsibility (if a largely unfulfilled and highly contested one) that the state was widely understood to have toward its citizens in the first place (see Benton, Citation2015).

In Belize, I struggled to understand why I never heard anything like this during my research. With so many people with diabetes dying preventable deaths and sustaining other losses all around me, patients seemed to mostly implicate themselves and to take the limits of the state system in measured stride. Some people called the opportunity to get one subsided dialysis session a week (although three were recommended to survive) a ‘scholarship.’ People in crisis largely focused on getting to other places they could receive the sessions, especially if they had some kind of mobility – some even making the three-times a week trip to Chetumal in Mexico, or more affluent citizens trying to find a route to Miami, LA, or Chicago – rather than agitating for infrastructural change within their state. Economist Albert O. Hirschman (Citation1972) famously described the channels through which people respond to local injustices: voice, loyalty, exit. Perhaps it would be fair to say that many Belizeans facing trouble (health or otherwise) have historically been in the habit of focusing on exiting their tiny country when infrastructures become strained.

One of the key places that diabetes complications were most dramatically surfacing in Belize was around rising anxieties about injured limbs and the threat of amputations. Wear on the vascular system due to complications of high blood sugar over time can de-capacitate the body’s ability to heal itself, and also contribute to the painful nerve damage of neuropathy. One U.S. study about the causes of diabetes limb amputation found at least 23 unique causal pathways in play (including 46% lost to ischemia, 59% to infection, 61% to neuropathy, 81% to faulty wound healing, 55% to gangrene, and 81% to initial minor trauma). Those numbers add up to 383% instead of 100% because most amputations are caused by several mechanisms simultaneously – which is also why remediating any one pathway will not necessarily save a limb. The biggest pattern this study found was that up to 80% of amputations were proceeded by a ‘pivotal event,’ usually a minor cutaneous injury (Pecoraro, Reiber, & Burgess, Citation1990). Tiny catastrophes such as a pebble in a shoe, an ingrown toenail, or stepping on a seashell can easily lead to a lost limb for someone with advanced diabetes, particularly once kidney complications were at play.

In ‘What Wounds Enable,’ anthropologist Laurence Ralph describes a phenomenon of people impacted by specific kinds of patterned injuries finding ways of ‘living through injury,’ allowing for fuller description of ‘contexts in which it becomes politically strategic to inhabit the role of a ‘defective body’ in order to make claims’ about connections between bodily injury and social injury (Ralph, Citation2012). I find this ethnographic concept work useful for grappling with these health struggles ongoing in Belize, and in particular the willingness of patients like Cruz to at times make their intimate injuries public in order to bring attention to wider social issues around their pending amputations.

The relaxed atmosphere in Belize often noted by tourists can easily be misrecognised for an absence of social problems in the country, rather than a hard-won effect of the way people absorbed hardship and undertook the labour of transmuting it for those around them. Yet many Belizeans also struggle with the stresses of embattled issues that adjacent countries like Guatemala and Mexico are well-known for in U.S. media – including income inequalities and persistent poverty, insecurities and traumas, murder rates that regularly rank as the leading causes of death among men and further deplete overstrained health systems (Anderson-Fye et al., Citation2010; Gayle et al., Citation2010). The normalisation of various forms of structural violence, it seemed to me, had complexly become part of ‘what it means to be human in a place advertised as paradise’ (Rodriguez, Citation2007, p. 221). There was often little opening to talk about such everyday stressors on bodies, or to probe the transnational contours of a system where healthy food and preventative care were difficult for many people to consistently access. Missing fingers, toes and limbs became a haunting endpoint of ongoing colonial legacies and at times occasioned rare discussions about the role of larger systems in shaping the choices available to people. This opened space for discussions about often-inchoate forms of ‘slow violence’ (Nixon, Citation2012; see Adams, Burke, & Whitmarsh, Citation2014) in the country, reflections on a system leading increasing numbers of people to need dialysis for survival in the first place (). According to these voices, responding to compounding chronic realities would require not only maintaining but reinventing existing public infrastructures for care.

‘Dr. Cruz’

‘It is open for us to affect human history,’ Jose Cruz had told me on the morning we met. By that time, in September 2010, he had already gone blind and was missing one leg and several fingers. Cruz had been holding a poster in the same injured hand the first time I had seen a picture of him in the newspaper. Cruz’s unnervingly modest message scrawled on yellow posterboard – WE DON’T WANT TO DIE – could be read with different inflections against this presumed fatalism on the part of such patients. In this context of normalized deaths, what gets branded as fatalism? What are the circumstances in which someone has to announce on a poster their wish to live on? Realism about the actual proximity of death could easily blur into what could be read as a certain resignation to it. It therefore became a major feat of advocacy just to counter the assumptions about diabetes and dialysis patients that were so often repeated.

On one hand, the extreme time and travel commitment required of rural patients needing dialysis meant some people did not consider the benefits worth the costs in their particular case, a deeply personal choice that many patients uneasily faced. On the other hand, some individuals’ difficult decision to forgo spottily accessible dialysis (given the numerous costs and obstacles of various kinds) certainly did not apply to everybody in Belize – an inaccurate assumption that I heard many patients worry had come to be accepted, in ways that normalised not providing dialysis to those people who did want and urgently need it in order to live.

‘I’m a young man trapped in an old man’s body,’ Cruz told me with a laugh. He was first diagnosed with diabetes when he was 28 years old. ‘The problem with diabetes is that it has different effects,’ he said slowly. ‘For example, because they did not diagnose the problem in time, I suffer retinopathy in both eyes … my vision went in a span of about two years.’ It turned out that Cruz lived for many years with the diagnosis of diabetes, before finally learning that his high blood sugar was actually rooted in a deeper pathology: polycystic kidney disease. This genetic disorder causes constant little cysts on the kidneys to grow and burst, causing infection that in turn triggered Cruz’s high blood sugars. ‘Over 500,’ he said of his glucose during times of infection. ‘When that happens, it makes dialysis … complicated.’ (Dialysis can also raise the sugar of the blood being returned to the body.) He preferred to arrive shirtless for his sessions and then be covered with a sheet. He was famous for making other patients laugh with his overdone singing during the awkward first part of treatment while their fistulas get connected to the machine, mostly Spanish ballads learned from his grandfathers. ‘It kills the time a little faster.’

‘There is going to be a lot more, because of the erasure of diabetes and hypertension,’ Cruz said of kidney failure cases ahead. He described how in his western home district of Cayo, patients still had to pay for insulin and antidiabetic medications themselves, or go without them. He worried that many Belizeans accepted the fragility of healthcare system – they are ‘used to it,’ in his words – and often asked for nothing more. ‘Because, they determine, because we’re in a third-world country. That’s the reason I am so much an advocate of critical dialysis,’ he told me. Their advocacy had gained a powerful immediate goal when the group learned about a letter from a U.S.-based organisation, which had offered to supply dialysis machines and train personnel if the Belizean government agreed to refurbish two unit locations and commit to certain care criteria over time. Cruz called the U.S. organisation himself when he learned that the letter had gone unanswered. He recalled their office hung up the first time he telephoned, suspecting a prank because they were unfamiliar with his accent.

Cruz called back. ‘I was told it couldn’t be done,’ he said, flashing a mischievous grin. ‘We deserve to have good healthcare in this country … .For the individual … in the population, no? As part of the population.’ At some point, fellow kidney patients and their families began calling him ‘Dr. Cruz,’ a striking nickname to emerge from a context where patients were getting dialysis without a physician. Cruz became both patient in and doctor of the system. ‘But you can see the doctors are circling up already. That is what I’m doing. Despite the fact that I’m always fighting with them. That is part of it, fighting all the time or it is never going to happen.’

One young woman a few years older than me, who I'll call Katherine, said the chances this opened had changed her life. She wore her long dark hair straight down her shoulders, and travelled 250 miles each week for the sessions. Her son loved Spiderman, she smiled. In her late twenties, Katherine said, the diabetes and kidney troubles developed during pregnancy. Her son was five by the time we met, and lived far south with her parents in Toledo; Katherine didn’t want him to move to Belize City because so many children had been caught in the violence, and she worried about putting him in danger. Her strategy, instead, was to arrive with her suitcase packed at every Friday session, ready to undergo the trip to her parents’ village to see him for the day on Saturday before making the return trip on Sunday to be back in Belize City for Monday dialysis.

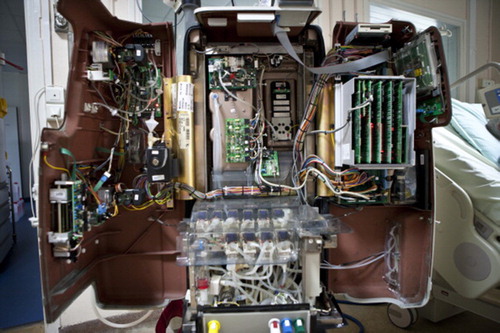

As Katherine told me this, intricate feats of fluid mechanics were occurring in tubes inside the machines around us. Blood flowed in one direction, and clear dialysate fluid (technically, ‘a buffered electrolyte solution’) in the other. The liquids were being brought together inside an encased plastic cylinder about a foot long, which is the dialyzer cartridge that actually serves as ‘artificial kidney,’ dwarfed and fed by the larger mechanical apparatus. The cartridge simulates the work of a glomerulus (Latin meaning ‘little ball of yarn’) – the knotted balls of vessels and fibres that make up the kidney’s semi-permeable membrane for filtering toxins. Today most semi-permeable membrane simulations use a new mechanism, a far cry from the original sausage casings model: Blood is channelled inside tiny hollow fibres, each only about the width of three human hairs, capillaries submerged in a bath of dialysis solution inside the cartridge’s inner chamber. Very small pores in the fibres’ walls keep larger molecules, such as blood cells and proteins that need to be returned to the body inside the filtering membrane. But smaller molecules of accumulating toxins, including chemicals like potassium, sodium, and bicarbonate that can rise to dangerous levels in the blood without a kidney, spin out through the tiny pores and dissolve into the chamber’s fluid. Invisibly laden with waste, salt, and extra water from the blood, the used dialysis solution drains into the wall behind the machine.

When I left the dialysis centre the last time we spoke, Cruz was belting out I’m Singing in the Rain in a comedic operatic voice, the patients around him laughing with a shake of their heads. The image of him waving goodbye with a three-fingered hand while singing so theatrically stuck with me. His routine performances’ feeling of a serious joke remained larger than life in my memory. And so did the first picture I had seen of him on the news in 2009. Cruz had both legs then, marching in the midst of a protest in Belize City. One of his hands still had all the fingers. But he held the sign in the other side, and the missing few read as part of his message: A PROMISE IS A CONSOLATION TO A FOOL.

Pressure and the press

João Biehl (Citation2016) describes two ways that patient-citizens in Brazil are learning, in their words, ‘to enter justice’ around their state’s constitutional right to health: one can either enter through the court’ (by filing a lawsuit for access to medications), or ‘enter through the press’ (by getting media coverage about missing rights that puts public pressure on the state for upholding them). In some ways, the press side of this work reminds me of Jose Cruz’s press releases. But in a country like Belize without any right to health written into a constitution or otherwise legible in a court of law, what do such tactics become when they rely on media outlets alone? What bodies are they meant to put pressure on?

People in Belize spoke constantly of rising ‘pressure,’ which commonly went hand in hand with high sugar (especially when diabetes complications such as kidney failure begin to show their signs). Indeed, in the common phrasing (‘I have pressure’) it was often literally impossible to tell if someone meant high blood pressure or escalating social pressure, or simply both at the place where they could not be separated (Banerjee, Citation2013). The work of transforming it from lethal blood pressure straining individual biologies, to creating ‘fields of pressure in public consciousness’ (Fischer, Citation2003, p. 265) that might drive state institutions toward building a healthcare or regulatory system that could potentially redress these risks, required a bold experiment in collective solidarity.

Cruz’s strategy of leveraging media publicity began as something improvised, rather than planned in advance. When Cruz’s foot became infected, the dialysis nurse ‘complained to management that she needed a doctor but could not get one’ (Ramos, Citation2009, p. 1). As a consequence, Cruz lost part of his foot. National papers covered the story. One article quoted the patient: ‘“I’m gonna be having a toeless Christmas. It’s sad,” said Cruz, laughing to lighten the mood.’ Shortly afterwards, the only dialysis nurse in Belize quit, saying she would come back only if a doctor was also on staff. ‘Only in Belize can you get dialysis without a nephrologist present, only in Belize. That is not right,’ Cruz said; the patients had joined together refused to sign the permanent waiver that a doctor need not be present for patients on the dialysis machine. ‘When our pressure goes up, God is the doctor,’ added Jose’s cousin [Ms. C] (Ramos, Citation2009). Cruz campaigned the Belizean media, calling into radio and TV stations: ‘From a patient standpoint we want a doctor, if it’s even a General Practitioner … along with our nurse. We want our nurse back’.

In the wake of public protest, the hospital accepted the dialysis collective’s terms. Their momentum grew. Shortly afterward, another story about Cruz appeared in the paper. ‘I need $150,000 by Monday because I could lose my whole hand,’ Cruz told the media; his left foot had been amputated only the month before (Citation7 News Belize, Citation2010, January Citation15). The papers ran his bank account number and cell, for Belizeans to contact him directly. Support poured in from around the country. Amazingly, he got the large sum (though it took costly time), and departed for Guatemala on 10 February 2010. With this medical intervention, Cruz lost two fingers but kept the rest of his hand. Even after his leg was later amputated, he continued leading protests in his wheelchair. In another photo, the stump of his leg still wrapped in a fresh bandage, Cruz holds another handprinted sign painted with a skull and crossbones.

In trying to puzzle out what such media images might ask of us, I remembered Ariella Azoulay’s notion that some photographs might act as ‘civil contracts’ (Citation2012) that at times capture specific injustices that cannot be addressed in their own context or political moment. Maybe it is possible, she writes, that they will make a claim on people in another place or time. Perhaps it was in a similar spirit to Azoulay’s hope for images that Cruz organised these impromptu press conferences for his amputations, or that so many patients I met wanted people in other countries to see their pictures. Photographs of these street protests, strategic press releases, and personal stories became the vital materials through which patients like Cruz were attempting to cobble an alternative possibility of politics or reassemble future visions of rights, at times choosing to publicly share and reconceive of their hardships – even seeking out public platforms to actively perform and display them – as they tried to press for a different future.

The doctors, nurses, family members and policy makers who eventually came to join in this struggle recognised that this particular struggle contained larger questions: How does a body extend into structures around it? Where does an injury begin or end? Organs, limbs, and senses will wear down without care. A common answer to How are you doing? in Belizean Kriol is ‘trying to maintain.’ Treating the complications of diabetes has long entailed what E. Brown calls ‘halfway technologies’ (Citation1996; see also Feudtner, Citation2003) – devices that help address ‘symptoms or manifestations of disease, rather than the underlying pathogenesis.’ Such halfway technology ‘does not treat the underlying disease itself, but reflects the absolute failure of all efforts at medical and conservative therapy and is a last ditch, gerry-rigged lifesaving solution.’ And yet, Brown adds, ‘when a ‘halfway’ technology is also lifesaving, its value cannot be underestimated by the individual patient.’ Preventative and prosthetic devices might allow health to be extended, but requires that bodies and infrastructures be maintained together (Russel & Vinsel, Citation2018).

Holding measures

Annemarie Mol describes ‘tinkering’ around chronic conditions as ‘an open-ended process: Try, adjust, try again. In dealing with a disease that is chronic, the care process is chronic, too. It only ends the day you die’ (Citation2008, p. 20). Because Cruz’s work to create an idea of rights took place largely through the news stories written about him, I am trying to take seriously the different work of narrating them myself. As anthropologists have shown in thinking with Stanley Cavell’s ‘active awaiting’ to reexamine care relations, time is a key horizon, and the centre of gravity shifts depending on where you stop or start the story (Han, Citation2012). I could choose to end here, for example, by telling you about people I knew who died over the years tinkering and waiting for the dream of dialysis to become a reality – like Sulma, whose daughter once called me at midnight to come over, but there was nothing either of us could really do as we stood together while her fifty-year-old mother ran frenetically around the house. She was flailing but unable to breathe as her lung condition was exacerbated by the sequelae of kidney damage, appearing to choke on the air as if underwater. Or Jordan, whose organs failed for the last time at the age of twenty one, after a brief lifetime as a Type 1 patient unable to consistently access insulin. There was nothing really to say when he showed me his bloated feet and said that he was not even on the dialysis waiting list; apparently his kidneys were so badly damaged that he was considered a poor candidate for the costly treatment.

But I could also tell a more heartening story about what I saw when I returned to Belize and saw the same location where, almost five years before, Ethan had shown me around the hospital’s garage of abandoned machines and the old watchman’s quarters being converted to make space for the newly arriving dialyzers they hoped to install. He was gone by the time I returned, moved on to mission work elsewhere. Jose Cruz died on a December morning, three months after I interviewed him in 2010. But there it was on the hill, landscaped with dirt rumoured to come from recently dug oil wells: a low building and a small sign directing patients into a Memorial Dialysis Unit.

It took me a minute to compose myself enough to take a picture of the open clinic, thinking of the past lives its sign marked and ongoing ones it might now extend. But I suppose you can’t freeze-frame a happy ending any more than a tragic one. Inside the unit, two visiting dialysis nurses bustled around, reflecting the transnational circuits of dialysis nursing expertise. Later that week, a government official worried aloud that the U.S. donor who had originally funded the centre had now withdrawn after three years of training and support (as had been planned), leaving the machines to the state for maintenance. A significant percentage of Ministry’s entire operating budget was being spent to keep the dialysis centres running, leaving nationwide limitations in more basic technologies – such as glucometers and strips for home testing (which were too expensive to be provided by the state) and insulin (now provided in 3 of its 6 districts) – which will mean more Belizeans needing dialysis in years ahead. Government officials are now looking for investors to help them maintain the units, and hoping to find a partner state abroad. Some in the Ministry of Health have become key dialysis advocates themselves, while balancing tough resource issues of scaling up (7 News Belize, Citation2011, February 4). By 2018, the programme’s coverage expanded to reach 25% of patients on the waiting list.

Among this number, getting dialysis in the room that morning I checked back in, was my old friend Guillerma. We had first met many years ago when her mother, a renowned midwife and herbalist, had hosted an ancestral ritual for health and protection during a time when she worried Guillerma might be dying from diabetes complications and could not get dialysis at all. The last time I had seen Guillerma was in a Belize City hospital in fall of 2010, when she had just started getting one of the three dialysis sessions that she needed each week, due in large part to Jose Cruz’s advocacy. It was a fraction of the care she needed, but had still opened some precarious margin of survival.

Sitting there years later in the new dialysis unit, where Guillerma was now getting between two and three weekly sessions, these histories meant something different already. But they were also part of the repair work (Schubert, Citation2019) that had sustained her until now. I showed Guillerma the picture I had taken during my last visit, when she had been sitting in the same chair in Belize City where Jose Cruz once received treatment; though the two had never met, she told me. ‘Tell them, I am still right here fighting it,’ she said, many years later then. Three days every week, she woke up at 4am and took a taxi and then a public school bus three hours in each direction in order to receive her hard-won session.

The dialysis machine whirred and beeped next to us the entire time we spoke, like a shrill but persistent third voice in our conversation, as it removed accreted toxins from Guillerma’s blood. In many parts of the world, dialysis is considered a ‘holding measure’ (Mitaishvili, Citation2010) until renal transplant becomes possible. But in Belize, where no renal transplant has yet been performed in the country’s history, dialysis instead became a ‘holding measure’ against death. It is waiting in this holding measure with Guillerma that I want to end here, trying to co-envision how to remain with these long-term maintenance projects – including ethnographic ones – now unspooling further contingencies ahead.

I remember how mechanical those exact machines had looked back in 2010, still stiffly wrapped in factory plastic, when I had photographed them in their storage room with the AC blasting to preserve their delicate parts. Seeing them surrounded by people and care, it was somehow comforting that the medical tubes carrying her blood into the machine for cleansing looked more pliable than I expected: less the electrical circuitry of a cyborg, more like an umbilical cord (). Guillerma followed my eyes. ‘Still alive,’ she smiled. The electrodes and wires thread the air between us, awkward and alive, into its tenuous machinery. Together we watched the centrifuge wheel her blood backwards like a wildly broken clock, trying to turn back enough time for the week ahead.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to all of those who spoke with me in Belize, and hope this is a gesture of recognition both for those ‘still fighting it’ and those ‘not here.’ Special thanks are also due to the Belize Institute for Social and Culture Research (ISCR) and the Belize Ministry of Health for their collaborative input and research approvals that launched this project, and the guidance of patients, families, and physicians in Belize. The complexities described offered here are offered here in the spirit of mutual care and critical inquiry, with much respect for all of these actors’ difficult work. Thanks to the institutional funders below that generously supported this project; to my great teachers in the Department of Anthropology at Princeton and to my wonderful colleagues in MIT Anthropology; and to Emily Vasquez for her exceptionally caring editorial work on this special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Amy Moran-Thomas http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5411-1046

Additional information

Funding

References

- 7 News Belize. (2009, December 30). Dialysis patients protest. Retrieved from http://7newsbelize.com/sstory.php?nid=15872

- 7 News Belize. (2009, July 1). Jose Cruz refuses dialysis in protest. Retrieved from http://www.7newsbelize.com/sstory.php?nid=14397

- 7 News Belize. (2010, January 15). Jose Cruz needs $15,000 to save his fingers. Retrieved from http://www.7newsbelize.com/sstory.php?nid=15995

- 7 News Belize. (2011, February 4). Dialysis, finally a public health reality. Retrieved from http://7newsbelize.com/sstory.php?nid=18867

- Adams, V., Burke, N. J., & Whitmarsh, I. (2014). Slow research: Thoughts for a movement in global health. Medical Anthropology, 33(3), 179–197. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2013.858335

- Anderson-Fye, E., et al. (2010). Cultural change and posttraumatic stress in the life of a Belizean adolescent girl. In C. Worthman (Ed.), Formative experiences: The Interaction of caregiving, culture, and developmental psychobiology (pp. 331–343). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Appel, H., Anand, N., & Gupta, A. (2015). Introduction: The infrastructure toolbox. Cultural Anthropology online series, “Theorizing the Contemporary”. Retrieved from https://culanth.org/fieldsights/714-introduction-the-infrastructure-toolbox

- Arredondo, A., Azar, A., & Recamán, A. L. (2017). Diabetes, a global public health challenge with a high epidemiological and economic burden on health systems in Latin America. Global Public Health. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17441692.2017.1316414

- Azoulay, A. (2012). The civil contract of photography. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Banerjee, D. (2013). Writing the disaster: Substance activism after Bhopal. Contemporary South Asia, 21(3), 230–242. doi: 10.1080/09584935.2013.826623

- Belize News 5. (2003). First dialysis centre opens in Belize. Retrieved from http://edition.channel5belize.com/archives/15509

- Benton, A. (2015). HIV exceptionalism: Development through disease in Sierra Leone. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Biehl, J. (2016). Patient-citizen-consumers: Claiming the right to health in Brazilian courts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Global Health and Medical Humanities Colloquia. April 14, 2016.

- Biehl, J., & Petryna, A. (Eds.). (2013). When people come first: Critical studies in global health. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Blakeslee, S. (2009, February 12). Williem Kolff, doctor who invented kidney and heart machines, dies at 97. New York Times, online edition. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com.

- Bolland, N. O. (1977). The formation of colonial society: Belize, from conquest to crown colony. Johns Hopkins Studies in Atlantic History and Culture. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Brown, E. 1996. Halfway technologies. Physician Executive, 22(12), 44–45.

- Bukhman, G., Bavuma, C., Gishoma, C., Gupta, N., Kwan, G. F., Laing, R., & Beran, D. (2015). Endemic diabetes in the world’s poorest people. The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology, 3, 402–403. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00138-2

- Clegern, W. (1967). British Honduras: Colonial dead end, 1859–1900. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana University Press.

- de-Graft Aikins, A., Addo, J., Ofei, F., Bosu, W., & Agyemang, C. (2012). Ghana’s burden of chronic non-communicable diseases: Future directions in research, practice, and policy. Ghana Medical Journal, 46(2S), 1–3.

- Feudtner, C. (2003). Bittersweet: Diabetes, insulin, and the transformation of illness. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Fischer, M. M. J. (2003). Emergent forms of life and the anthropological voice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Gayle, H., Mortis, N., Vasquez, J., Mossiah, R. J., Hewlett, M., & Amaya, A. (2010). Report: Male social participation and violence in urban Belize. Belize City: Belize Ministry of Education.

- Grant, C. H. (1976). The making of modern Belize: Politics, society and British colonialism in Central America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Geertz, C. (2000). Available light: Anthropological reflections on philosophical topics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gough, E., Emmanuel, E., Jenkins, V., Thompson, L., et al. (2011). Survey of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic disease risk factors: CAMDI survey of Central America. Washington, DC: PAHO/WHO. Retrieved from http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6345%3A2012-camdi-survey-diabetes-hypertension-chronic-disease-risk-factors-centro-america-2012&catid=4045%3Achronic-diseases-news&Itemid=40276&lang=en

- Hamdy, S. (2008). When the state and your kidneys fail: Political etiologies in an Egyptian dialysis ward. American Ethnologist, 35(4), 553–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1425.2008.00098.x

- Han, C. (2012). Life in debt: Times of care and violence in neoliberal Chile. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hatch, A. R. (2016). Blood sugar: Racial pharmacology and food justice in Black America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1972). Exit, voice, and loyalty. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hoover, E. (2017). The river is in us: Fighting toxics in a Mohawk community. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Huxley, A. (1934). Beyond the Mexique Bay. London: Chatto & Windus.

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). (2017). Diabetes atlas (8th ed.). Retrieved from https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/2017-atlas.html

- Manderson, L., & Smith-Morris, C. (Eds.). (2010). Chronic conditions, fluid states: Chronicity and the Anthropology of Illness. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Mendenhall, E., & Norris, S. (2015). When HIV is ordinary and diabetes new: Remaking suffering in a South African Township. Global Public Health, 10(4), 449–462. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.998698

- Mitaishvili, R. (2010). Dialysis: Complete textbook of dialysis. Los Angeles, CA: RM Global Health.

- Mol, A. (2008). The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Montoya, M. (2013). Potential futures for a healthy city: Community, knowledge, and hope for the sciences of life. Current Anthropology, 54(S7), S45–S55. doi: 10.1086/671114

- Narres, M., Claessen, H., Droste, S., Kvitkina, T., Koch, M., Kuss, O, & Icks, A. (2016). The incidence of end-stage renal disease in the diabetic (compared to the non-diabetic) population: A systemic review. PLoS One, 11, e0147329. Retrieved from http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0147329

- Nielson, J., Bahendeka, S. K., Bygbjerg, I. C., Meyrowitsch, D. W., & Whyte, S. R. (2017). Accessing diabetes care in rural Uganda: Economic and social resources. Global Public Health, 12(7), 892–908. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1172100

- Nixon, R. (2012). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pecoraro, R., Reiber, G., & Burgess, E. (1990). Pathways to diabetic limb amputation: Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care, 13(5), 513–521. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.5.513

- Ralph, L. (2012). What wounds enable: The politics of disability and violence in Chicago. Disability Studies Quarterly, 32(3). Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/lauralph/publications/what-wounds-enable-politics-disability-and-violence-chicago

- Ramos, A. (2009). Dialysis patients, kidney association cry for help. Amandala, December 15.

- Rettig, R. A. (2011). Special treatment—The story of Medicare’s ESRD entitlement. New England Journal of Medicine, 364, 596–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1014193

- Roberts, E. (2017). What gets inside: Violent entanglements and toxic boundaries in Mexico City. Cultural Anthropology, 32(4), 592–619.

- Rodriguez, R. (2007). Disappointment. In D. F. Wallace (Ed.), Best American essays (pp. 221–233. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

- Russell, A., & Vinsel, L. (2018). After innovation, turn to naintenance. Technology and Culture, 59(1), 1–25. doi: 10.1353/tech.2018.0004

- Sanal, A. (2011). New organs within us: Transplants and the moral economy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Scott, J. (1990). Domination and arts of resistance: Hidden transcripts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Schubert, C. (2019). Repair work as inquiry and improvisation. In I. Strebel, A. Bovet, & P. Sormani (Eds.), Repair work ethnographies: Revisiting breakdown, relocating materiality. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Solomon, H. (2016). Metabolic living: Food, fat, and the absorption of illness in India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stone, M. (1994). Caribbean nation, central American state: Ethnicity, race, and national formation in Belize, 1798–1990 ( PhD diss.). University of Texas, Austin.

- Wilk, R. (2006). Home cooking in the global village. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Global report on diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf

- Yates-Doerr, E. (2015). The weight of obesity: Hunger and global health in postwar Guatemala. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.