ABSTRACT

Women comprise two-thirds of the global-health (GH) workforce but are underrepresented in leadership. GH departments are platforms to advance gender equality in GH leadership. Using a survey of graduates from one GH department, we compared women’s and men’s post-training career agency and GH employment and assessed whether gender gaps in training accounted for gender gaps in career outcomes. Master-of-Public-Health (MPH) and mid-career-fellow alumni since 2010 received a 31-question online survey. Forty-four per cent of MPH alum and 24% of fellows responded. Using logistic regression, we tested gender gaps in training satisfaction, career agency, and GH employment, unadjusted and adjusted for training received. Women (N = 293) reported lower satisfaction with training (M7.6 vs 8.2) and career agency (leadership ability: M6.3 vs 7.4) than men (N = 60). Women more often than men acquired methods-related skills (95% vs 78%), employment recommendations (42% vs 18%), and group membership. Men more often than women acquired leadership training (43% vs 23%), award recommendations (53% vs 17%), and conference support (65% vs 35%). Women and men had similar odds of GH employment. Accounting for confounders and gender-gaps in training eliminated gender gaps in five of six career-agency outcomes. Panel studies of women’s and men’s career trajectories in GH are needed.

Introduction

Women comprise two-thirds of the global-health (GH) workforce (Magar, Gerecke, Dhillon, & Campbell, Citation2016) and contribute US$3 trillion to GH care; however, nearly half of this care is unpaid (Berg & Woods, Citation2009; Dhatt et al., Citation2017; Magar et al., Citation2016; Morgan et al., Citation2018). Women also are under-represented in GH leadership positions across academic, governmental, and non-governmental institutions (Barry et al., Citation2017; Dhatt et al., Citation2017; Downs, Reif, Hokororo, & Fitzgerald, Citation2014; Talib, Burke, & Barry, Citation2017). Only one in four countries have a woman minister of health (Magar et al., Citation2016); less than one in four global-health-center directors of the top 50 medical schools are women (Downs et al., Citation2014); and, only two of six heads of health-related UN agencies are women (Morgan, Dhatt, Muraya, Buse, & George, Citation2017). In the Hubert Department of Global Health at Emory University, most undergraduate minors (91%) and masters students (84%) are women; however, a majority of mid-career fellows (60%), full and named professors (75%), and endowed professors (85%) are men. Women, including women of colour, sexual minority women, indigenous women, other minority women groups, and women from lower-income countries remain under-represented in GH leadership (American Association of University Women, Citation2016). The disparate barriers faced by women from different backgrounds must be addressed to ensure that their leadership capabilities are realised (Bowleg, Citation2012).

Beyond its relevance for gender equity and women’s rights, women’s leadership in GH matters for two reasons. First, women have unique health-related interests. They make up 50% of the world’s population, bear the unique burden of certain causes of death (Alkema et al., Citation2016), and experience more years than men of life lost due to disability (Vos et al., Citation2016). Empirically, women need to be in leadership positions to have their interests represented (Swers & Rouse, Citation2011). Second, women’s leadership in GH may benefit other marginalised groups. Having a higher share of women among community leaders has positively affected children’s learning and nutrition (Pathak & Macours, Citation2017), spending on family benefits (Ennser-Jedenastik, Citation2017), and spending for the poor (Courtemanche & Green, Citation2017). Women’s unique needs and contributions are strong rationales for gender equality in GH leadership. Equality in formal representation means having the same opportunities to participate in leadership, without discrimination on the basis of gender or other identities (Swers & Rouse, Citation2011). Equality in descriptive representation means occupying an equal number of positions of leadership (Swers & Rouse, Citation2011). Equality in substantive representation means that women’s interests are represented in decision-making circles (Swers & Rouse, Citation2011).

The 2017, 2018 Women Leaders in Global Health and 2019 Women Deliver conferences reconfirmed principles to advance women’s leadership, including in GH. These principles included ensuring gender balance in all spheres of academia, leadership mentoring, nominating and promoting women for important committees and awards, advocating for a culture that values work-life integration, eliminating gender gaps in pay, preventing sexual harassment in the workplace, cultivating thought leadership, collecting gender-disaggregated data to expose and to monitor trends in gender gaps, and promoting accountability (Dhatt et al., Citation2017; Mathad et al., Citation2019; Morgan et al., Citation2017; Talib et al., Citation2017).

Empowerment-based training models for gender equality in global health leadership

Sustainable Development Goal five (United Nations, Citation2015) identifies women’s empowerment as a pathway to achieve gender equality. Thus, empowerment-based educational models may be needed to advance gender equality in GH leadership (Downs et al., Citation2014; Talib et al., Citation2017). Kabeer (Citation1999) defines women’s empowerment as the process by which women claim new resources, which enhance their agency, or ability to make strategic life choices that advance their achievement of self-defined goals, in all domains. Research from LMICs (Cornwall, Citation2016) focuses on how women’s resources and agency may affect women’s nutrition (Sinharoy et al., Citation2018), mental health (Yount et al., Citation2018), sexual and reproductive health (James-Hawkins et al., Citation2016), and freedom from violence (Yount, Citation2005), as well as the health and nutrition of their children (Smith et al., Citation2002). The effects of women’s empowerment (resources and agency) on their career trajectories and leadership in applied and academic GH is understudied. Researchers and practitioners tend to operationalise women’s leadership as a domain of women’s empowerment rather than an achievement of this process (Alkire et al., Citation2013). An exception is research on women’s political participation, which Kabeer (Citation2005) has modeled as an outcome of women’s resources and agency. Political participation, however, does not capture political leadership.

Research mainly from higher-income countries focuses on the determinants of women’s leadership in education (Knipfer, Shaughnessy, Hentschel, & Schmid, Citation2017), healthcare (Levine, González-Fernández, Bodurtha, Skarupski, & Fivush, Citation2015), and business (Saleem, Rafiq, & Yusaf, Citation2017). Women leaders are lacking across disciplines, including GH (Dhatt et al., Citation2017; Rohde, Wolf, & Adams, Citation2016; Talib et al., Citation2017). Social inequalities and rigid gender roles help to explain the unequal treatment of women due to gender discrimination (National Academies of Sciences & Medicine, Citation2018) and masculinised leadership roles (Eagly & Karau, Citation2002). Institutional barriers, such as wage gaps (World Economic Forum, Citation2018), limited or no parental leave, and child-care costs can hinder women’s professional advancement (Carr, Gunn, Raj, Kaplan, & Freund, Citation2017). This deficit approach reveals the constraints on women’s opportunity to envisage themselves as leaders.

In the Hubert Department of Global Health at Emory University, we are asking a solution-oriented question: ‘Can empowerment-based models enable more women to attain leadership positions in GH?’ Training the next generation of women leaders in GH is one of three strategic priorities of departmental faculty who have developed an empowerment-based model to advance gender equality in GH leadership (Yount et al., Citation2018).

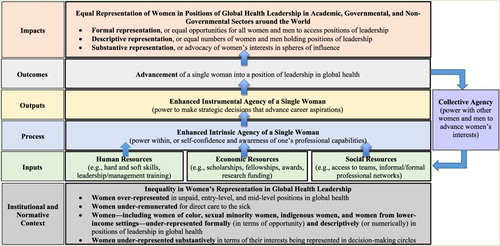

Drawing on Kabeer’s (Citation1999) framework, women’s empowerment in GH is the process by which women claim new human, economic, and social resources, enabling them to exercise agency, or the capacity to make strategic life choices to enhance their careers where these choices once were denied (). Human resources include theoretical and methodological training to acquire new knowledge and skills; opportunities to author publications with network affiliates; in-country practicums to strengthen experiential learning; guidance on building effective teams; discussions on emotional intelligence, such as negotiating one’s interests and managing professional conflicts; and training on ethics in GH. Economic resources include nominations for scholarships, fellowships, and awards; mentorship on grant writing; participation on funded team projects; and financial support to attend professional conferences. Social resources include integration into interdisciplinary, project-based teams; exposure to formal and informal professional networks; opportunities to attend professional conferences; introductions to professionals with similar career interests; and in-country internships to widen global networks. Social resources also include the amplification of professional accomplishments via social media, press releases, webinars, electronic newsletters, and blog posts.

Figure 1. Empowerment-based model to advance women’s leadership in global health.

Source: Adapted from Yount et al. (Citation2018).

Agency, an intermediate outcome, may arise from the above enabling resources. Intrinsic agency, or power within, entails self-confidence and awareness of one’s professional capabilities. Instrumental agency, or power to, entails the enactment of strategic decisions that advance one’s career aspirations. Collective agency, or power with, entails a group's shared belief in its joint capabilities to execute mutually agreed actions that advance shared interests. More than the sum of individual agencies, collective agency emerges from synergy within the group (Bandura, Citation2000). Intrinsic and instrumental agency, as individual-level outcomes, are rarely examined in mentoring models (Hopwood, Citation2010), and collective agency has never been conceptualised or measured as an outcome of network-based mentorship models.

Here, we report findings from a cross-sectional survey of departmental graduates undertaken to test core elements of this model. The survey allowed us to address three research questions: Are there gender gaps in the resources that men and women receive during GH training?; Do women report lower post-training career agency than men?; and Do any gender gaps in resources acquired during GH training account for any gender gaps in post-training career agency and employment in GH?

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

We conducted an online, cross-sectional survey of master-of-public health (MPH) alumni and non-degree-seeking mid-career fellows who completed their GH training since 2010. MPH training typically involves two years of coursework, a field practicum in the United States or abroad, and a thesis or special project. For dual-degree and executive MPH students, coursework typically is condensed into one year. Mid-career fellows include MPH degree-seeking and non-degree seeking students across a range of fellowship programmes, some of which also involve leadership training. The study team received a human-subjects exemption from the Emory University IRB before study commencement. An initial email invitation to participate was distributed to MPH alumni and mid-career fellows on February 5, 2018. The survey procedures were described, and written informed consent to participate was obtained before the survey was administered. Three reminders were sent 12–18 February 2018 to those who had not responded to the survey. Of 762 MPH alumni invited to participate, 334 (or 43.83%) took part. The response rate for non-degree-seeking fellows was 24.28%.

The survey (Supplemental Table A.1) was administered using SurveyMonkey, a HIPAA-compliant online platform, and included 31 questions about demographics (country of upbringing/residence, gender, age, racial/ethnic heritage, contact details); dates of training and highest degree attained; leadership experiences before and during GH training; human, social, and economic resources received during training; satisfaction with GH training; post-training career agency; and current employment in GH.

Outcomes

We explored seven outcomes. Six outcomes captured satisfaction with GH training and post-training career agency. These outcomes were derived from questions originally scored on a 10-point scale, measuring how much (not at all = 0, moderately = 5, extremely = 10) the respondents were (1) satisfied with their GH training and perceived that their training (2) enhanced their professional confidence, (3) prepared them for their current professional role, and enhanced their abilities to (4) negotiate their professional interests, (5) advance professionally, and (6) lead. We dichotomised these outcomes to distinguish the highest tertile from the lower two tertiles, as we were interested in the differences between these two score levels. To evaluate how robust the results were to a different classification scheme, we dichotomised the variables differently (highest quartile vs three lowest quartiles) and re-ran the models. We reached the same inferential conclusions about the structural relationships between the predictors and the outcomes (available on request). The last binary outcome captured whether or not the alum was working in GH.

Statistical analysis

Stata 15.0 statistical software was used for all analyses (StataCorp, Citation2017). Our main exposure variable was the trainee’s gender identity. The original question allowed respondents to self-identify as a woman, man, transgender woman, transgender man, other non-conforming gender, other, or no response. No respondents self-reported to be transgender, and two respondents preferred not to report a gender identity, so gender identity was collapsed according to self-identification as a woman or man (n = 351) or ascribed woman/man gender based on respondent’s name (n = 2).

Resource-related exposure variables captured the human, economic, and social resources depicted in . These resource variables included leadership experience during GH training (a focal human resource, coded 0 = none, 1 = group member, 2 = group leader) as well as summative scores for the number of other human resources (0–10), the number of economic resources (0–9), and the number of social resources (0–11) received during GH training. Potential confounders included leadership experiences before GH training (0 = none, 1 = group member, 2 = group leader), highest degree attained at Emory University (0 = MPH only, 1 = MPH with other degree, 2 = non-degree fellow), and racial or ethnic heritage (0 = White/European American, 1 = African/Afro-Caribbean/African American, 2 = Asian/Asian American, 3 = Arab/Arab American, 4 = Other).

Exploratory data analyses included methods to assess the central tendency, variability, distribution, and proportion of missing values for each variable. We applied t-tests and chi-square tests for independence to assess the significance of the relation between gender and continuous or categorical exposure, covariate, and outcome variables, respectively. Logistic regression models were used to assess the significance of gender differences in the odds of each outcome, unadjusted (Model 1) and then adjusted sequentially first for potential confounders (prior leadership roles and race/ethnic descent, Model 2) and then the resources received during GH training (Model 3). This sequential modeling approach allowed us to observe whether there were significant gender gaps in outcomes before and after adjustment for confounders, and whether any residual gender gaps in outcomes were eliminated with adjustment for gender differences in resources received during GH training. Less than one percent of participants had missing values on five outcome variables, and one participant had no information on gender. We excluded these surveys (N = 15) from the logistic regression models. To assess the robustness of our findings, we ran linear regression models on six of the outcomes in their original metrics as well as logistic regression models with different dichotomous categorisation schemes of these outcomes. We have focused on results for logistic regression models of the dichotomous outcomes described above because the effects expressed in the odds ratio of attaining a high level of each outcome were more intuitive and familiar to the public-health audience than those expressed in the original units.

Role of funding source

The home department provided support for research assistance and the online survey. Seven of the ten authors are faculty, students, or staff of the home department in which the survey was conducted.

Results

Quantitative findings

Women accounted for nearly 80% of the 353 respondents (). Women more often had completed the MPH programme (90% vs 63% for men); whereas, men more often had completed a non-degree fellowship (30% vs 5% for women). About half of women and men were employed in a GH-related field at interview (44% and 52%, respectively). Women largely self-identified as non-Hispanic white (67%); whereas, men were equal parts non-Hispanic white (32%); African, Afro-Caribbean, or African American (32%); and Asian or Asian American (27%). Less than 6% of women and men were of Latino, Arab, or other descent.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of alumni participants, global health leadership and empowerment survey.

presents the resources acquired through GH training, overall and by gender. On average, respondents received 4.5 human resources of ten listed, 2.0 economic resources of nine listed, and 3.5 social resources of 11 listed. Mean summative scores for human, economic, and social resources acquired during GH training were similar across gender. However, important differences were apparent in the specific resources that women and men received. Among the human resources, a higher percentage of women than men reported receiving skills-related training, including in research methods (95% vs 78%), evaluation design (72% vs 53%), authorship of a publication (42% vs 27%), and in-country practicum experience (69% vs 50%). By contrast, a higher percentage of men than women reported receiving training in GH ethics (27% vs 13%), leadership (43% vs 23%), and other topics (47% vs 18%). Among the economic resources, men reported more often than women to have been recommended for a fellowship or award (53% vs 17%) and to have received school-level funding for research assistantships (28% vs 12%); whereas, women reported more often than men receiving employment-related recommendations (42% vs 18%). Among the social resources, men reported more often than women to have attended professional conferences (65% vs 35%); whereas, women reported more often than men being members of project teams (46% vs 30%) and student organisations (53% vs 35%), leading student organisations (35% vs 18%), and completing in-country internships to extend global networks (45% vs 28%).

Table 2. Resources acquired during training in global health, global health leadership and empowerment survey.

On average, women and men reported higher than moderate (score = 5) satisfaction with GH training and career agency (). However, mean scores for these outcomes were consistently lower for women than men. Compared to men, women reported lower mean satisfaction with GH training (7.6 vs 8.2), as well as lower mean professional confidence (7.5 vs 8.2), ability to negotiate professional interests (6.4 vs 7.6), ability to lead (6.3 vs 7.4), professional advancement (7.7 vs 8.3), and preparation for their current professional role (7.1 vs 7.8). About half of women (44%) and men (52%) were employed in GH at interview.

Table 3. Satisfaction with GH training, career-related agency, and employment in global health, global health leadership and empowerment survey.

Consistent with findings in , women had consistently lower unadjusted odds than men of reporting higher satisfaction with training and post-training career agency (, Panel 1). These differences were attenuated with adjustment for prior leadership experience and race/ethnic heritage (, Panel 2). Accounting also for leadership experience and resources received during GH training (, Panel 3), women remained less likely than men to report higher satisfaction with GH training (aOR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.98) and marginally less likely than men to report higher professional preparation for their current employment (aOR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.29, 1.06); however, women were as likely as men to report higher career agency with respect to professional confidence (aOR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.34, 1.53), ability to negotiate professional interests (aOR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.37, 1.60), leadership ability (aOR: 0.61; 0.28, 1.34),and professional advancement (OR: 0.62; 95% CI 0.31, 1.27). Women and men had similar unadjusted and adjusted odds of being employed in GH (e.g. 0.98; 95% CI 0.51, 1.86 in Panel 3).

Table 4. Adjusted odds of scoring in upper tertile on satisfaction with training, career agency, and career outcomes, global health leadership and empowerment survey (N = 353).

In robustness checks (results available on request), we obtained similar inferential conclusions based on different metrics and thresholds regarding the unadjusted and adjusted gender gaps for five of six outcomes. Namely, for the dichotomous models based on tertiles, one gender gap (in training satisfaction) remained significant after adjustment. For the continuous models, two gender gaps (in training satisfaction and negotiation skills) remained significant after adjustment. For the dichotomous models based on quartiles, all gender gaps became non-significant after adjustment.

Qualitative findings

To contextualise these findings, we synthesised women’s and men’s responses to three open-ended questions in the survey capturing their greatest professional accomplishment attributed to GH training, recommendation of GH training (or not) to others, and anything else about their experience with GH training. A total of 368 participants answered these questions (292 women, 61 men, 15 others). We compared the responses of women and men for salient themes related to the resources they received during GH training and their career advancement.

Gendered reasons to recommend GH training

Overall, women recommended GH training slightly more often than men (70% vs 63%). Women and men, respectively, identified the strong network and community (31%, 28%) and coursework and skills developed (22%, 23%) as reasons to recommend GH training. Some women (6%) and men (8%) did not recommend GH training because of the financial costs of the degree programme.

Women and men expressed some differences in why they recommended GH training. Women (18%) more often than men (12%) recommended GH training for the practical experience and job opportunities, and men (28%) more often than women (15%) recommended GH training for the University’s, department’s, and faculty’s strong reputations. Slightly more women (5%) than men (2%) discussed the need for training in leadership and global programme management. According to one woman,

Project management and leadership … should be offered for … students … many brilliant researchers … [are] hampered by their lack of knowledge in organizational or project management. (female, South Asian or Indian American, MPH alumni, employed in global public health field)

Gendered professional accomplishments and reasons for them

Overall, most women (95%) and men (95%) attributed positive professional accomplishments to their GH training. Women (7%) and men (7%) attributed equally often authorship in a peer-reviewed journal to their training; however, four times as many women (21%) as men (6%) attributed being employed in public health to their training, and only women (4%) mentioned going on to receive a PhD or MD degree. According to one woman,

As a direct result of my training and opportunities … , I obtained a … fellowship at CDC upon graduation. That position, along with the foundation laid at Emory University, allowed me to get into the Epidemiology PhD program at Johns Hopkins with a full-funded scholarship. (female, non-Hispanic White, MPH alumni, employed in global public health field)

Women (26%) more often than men (21%) attributed their professional accomplishments to applying their coursework in professional settings; whereas, men (15%) more often than women (11%) attributed their professional accomplishments to networking and mentorship. Women uniquely mentioned that having women role models showed them that working in GH was not incompatible with marriage and family. According to one woman,

Having female role models [showed] me that working in global health was not incongruent with having a family, a marriage, and the life I wanted. (female, non-Hispanic White, MPH alumni, employed in global public health field)

Discussion

Summary of findings

Women’s under-representation in GH leadership is well-documented. Different groups of women – including women of colour, sexual minority women, and women from low-income countries – face unique barriers to cultivate their capabilities as GH leaders. Each barrier should be addressed to ensure women’s full representation in the highest ranks. Pilot data suggests that empowerment-based mentorship is a promising strategy to advance all women in GH (Yount et al., Citation2018).

The present study offered a cross-sectional assessment of this empowerment-based conceptual model. On average, respondents attributed high satisfaction and career agency to their GH training. Women reported more often than men acquiring human and social resources (skills, employment recommendations, and membership in student-based organisations); whereas, men more often reported acquiring human, economic, and social resources (leadership training, recommendations for awards, and opportunities to attend conferences). Women reported lower post-training satisfaction than did men; however, accounting for confounders and resources received during training largely eliminated gender gaps on five of six career-agency domains (professional confidence, negotiation skills, leadership ability, career agency, and professional advancement). Women and men had similar unadjusted and adjusted odds of employment in GH, although the type of employment (e.g. technical, team member, team leader, or director) was unknown. In qualitative interviews, women underscored the need for leadership training and valued having women role models, who showed that having a family and work in GH were possible.

Limitations and strengths

A response rate of 44% for MPH alum and 24% for non-degree-seeking fellows prevents us from drawing inferences to the population of GH trainees graduating since 2010. Also, small sample size precluded disaggregation of the mid-career fellows. This caveat is important because women and men are equally represented among some non-degree-seeking fellows and receive leadership training in their programme; whereas, the other fellows are MPH-degree-seeking. Small sample size also prevented us from exploring differences in training-related resources received and career outcomes for more differentiated gender-race-ethnic groups. Moreover, many graduates in the study sample, were still relatively early career at the time of the survey (), so would not have had opportunities for major leadership roles in GH. For this reason, the survey asked alumni about employment in GH, to measure gender gaps/equity in ‘retention’ in the field. Longitudinal follow-up of these graduates could assess career trajectories and long-term leadership roles in GH. Finally, the survey was cross-sectional, so findings should be interpreted as associational and not causal.

The study’s unique strengths are notable. To our knowledge, this is the first mixed-methods study by a multi-disciplinary team in an academic department of GH to assess gender differences in: the resources received during graduate and mid-career fellow training, satisfaction with GH training, post-training career agency, and employment in GH. Findings suggest that a resources-agency-achievements framework is useful to understand the mechanisms by which empowerment-based training for women in GH could enhance their capabilities for leadership in GH.

Implications for research and training

Our focus here on MPH graduates from an academic department of GH can be extended to include undergraduate minors in GH, pre- and post-doctoral fellows in GH, and other non-degree seeking fellows. A randomised controlled trial is needed to test the impacts of empowerment-based training models that invest human, economic, and social resources to advance women’s leadership in GH. Such a trial might compare self-reported career agency and objective outcomes, such as starting salary, raises, time to promotion, perceived work–family balance, managerial/leadership positions, and career satisfaction between (1) men who receive standard GH training versus women who are randomised to either (2) standard GH training or (3) supplemental empowerment-based training involving leadership development and resource-based mentoring from women role models. If effective, this empowerment-based model to advance women’s careers in GH could set the standard for graduate training in academic departments of GH and other disciplines.

Supplemental_Table_A1.pdf

Download PDF (210.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The Hubert Department of Global Health provided in-kind support from staff for the data collection. No one was paid by a pharmaceutical company or other agency to write this article. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

- Alkema, L., Chou, D., Hogan, D., Zhang, S., Moller, A.-B., Gemmill, A., … Say, L. (2016). Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: A systematic analysis by the UN maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. The Lancet, 387(10017), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7.

- Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development, 52, 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007.

- American Association of University Women. (2016). Barriers and bias: The status of women in leadership. Washington DC.

- Bandura, A. (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(3), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1111 doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00064

- Barry, M., Talib, Z., Jowell, A., Thompson, K., Moyer, C., Larson, H., & Burke, K. (2017). A new vision for global health leadership. The Lancet, 390(10112), 2536–2537. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33101-X.

- Berg, J. A., & Woods, N. F. (2009). Global women’s health: A spotlight on caregiving. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 44, 375–384. DOI:10.1016/j.cnur.2009.06.003.

- Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality – an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750.

- Carr, P. L., Gunn, C., Raj, A., Kaplan, S., & Freund, K. M. (2017). Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: How institutions are addressing gender disparities. Women’s Health Issues, 27(3), 374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.003.

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works. Journal of International Development, 28, 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3210.

- Courtemanche, M., & Green, J. (2017). The influence of women legislators on state health care spending for the poor. Social Sciences, 6(2), 40. DOI: RePEc:gam:jscscx:v:6:y:2017:i:2:p:40-:d:95937 doi: 10.3390/socsci6020040

- Dhatt, R., Theobald, S., Buzuzi, S., Ros, B., Vong, S., Muraya, K., … Lichtenstein, D. (2017). The role of women’s leadership and gender equity in leadership and health system strengthening. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics, 2. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2016.22.

- Downs, J. A., Reif, L. K., Hokororo, A., & Fitzgerald, D. W. (2014). Increasing women in leadership in global health. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(8), 1103–1107. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000369.

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

- Ennser-Jedenastik, L. (2017). How women’s political representation affects spending on family benefits. Journal of Social Policy, 46(3), 563–581. DOI:10.1017/S0047279416000933.

- Hopwood, N. (2010). A sociocultural view of doctoral students’ relationships and agency. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.487482.

- James-Hawkins, L., Peters, C., VanderEnde, K. E., Bardin, L., & Yount, K. M. (2016). Women’s empowerment and its relationship to current contraceptive use in low, lower-middle, and upper-middle income countries: A systematic review of the literature. Global Public Health, doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1239270.

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125.

- Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal 1. Gender & Development, 13(1), 13–24. doi: 10.1080/13552070512331332273

- Knipfer, K., Shaughnessy, B., Hentschel, T., & Schmid, E. (2017). Unlocking women’s leadership potential: A curricular example for developing female leaders in academia. Journal of Management Education, 41(2), 272–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916673863.

- Levine, R. B., González-Fernández, M., Bodurtha, J., Skarupski, K. A., & Fivush, B. (2015). Implementation and evaluation of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Leadership Program for women faculty. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(5), 360–366. DOI: doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5092.

- Magar, V., Gerecke, M., Dhillon, I., & Campbell, J. (2016). Women’s contribution to sustainable development through work in health: Using a gender lens to advance a transformative 2030 agenda. In J. Buchan, I. S. Dhillon, & J. Campbell (Eds.), Health employment and economic growth: An evidence base (pp. 27–50). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Mathad, J. S., Reif, L. K., Seo, G., Walsh, K. F., McNairy, M. L., Lee, M. H., … Nerette, S. (2019). Female global health leadership: Data-driven approaches to close the gender gap. The Lancet, 393(10171), 521–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30203-X

- Morgan, R., Ayiasi, R. M., Barman, D., Buzuzi, S., Ssemugabo, C., Ezumah, N., … Liu, T. (2018). Gendered health systems: Evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0338-5.

- Morgan, R., Dhatt, R., Muraya, K., Buse, K., & George, A. S. (2017). Recognition matters: Only one in ten awards given to women. The Lancet, 389(10088), 2469. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31592-1

- National Academies of Sciences, E., & Medicine. (2018). Sexual harassment of women: Climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Presshttps://doi.org/10.17226/24994.

- Pathak, Y., & Macours, K. (2017). Women’s political reservation, early childhood development, and learning in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 65(4), 741–766. https://doi.org/10.1086/692114.

- Rohde, R. S., Wolf, J. M., & Adams, J. E. (2016). Where are the women in orthopaedic surgery? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, 474(9), 1950–1956. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4827-y.

- Saleem, S., Rafiq, A., & Yusaf, S. (2017). Investigating the glass ceiling phenomenon: An empirical study of glass ceiling’s effects on selection-promotion and female effectiveness. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 6(3), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-04-2016-0028.

- Sinharoy, S.S., Waid, J.L., Haardoerfer, R., Wendt, A., Gabrysch, S., & Yount, K.M. (2018). Women’s. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, e12489. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12489.

- Smith, L.C., Ramakrishnan, U., Naidye, A., Haddad, L., & Martorell, R. (2002). The importance of women’s status for child nutrition in developing countries. Washington, DC.

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Swers, M. L., & Rouse, S. M. (2011). Descriptive representation: Understanding the impact of identity on substantive representation of group interests. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199559947.003.0011.

- Talib, Z., Burke, K. S., & Barry, M. (2017). Women leaders in global health. The Lancet Global Health, 5(6), e565–e566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30182-1.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development A/RES/70/1. New York. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

- Vos, T., Allen, C., Arora, M., Barber, R. M., Bhutta, Z. A., Brown, A., … Coggeshall, M. (2016). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. The Lancet, 388(10053), 1545–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

- World Economic Forum. (2018). The global gender gap report 2018. Geneva, Switzerland. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf..

- Yount, K.M. (2005). Resources, family organization, and domestic violence against married women in Minya, Egypt. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00155.x.

- Yount, K.M., Miedema, S.S., Clark, C.J., Chen, J.S., & del Rio, C. (2018). GROW: A model for mentorship to advance women’s leadership in global health. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics, 3, e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2018.5.