ABSTRACT

As part of a multisectoral response to gender-based violence (GBV), Nepal is testing the feasibility of having female community health volunteers (FCHVs) play a formal role in identifying GBV survivors and referring them to specialised services at health facilities. This study followed 116 FHCVs in Mangalsen municipality who attended a one-day orientation on GBV. Over the following year, data were collected from knowledge and attitude assessments of FCHVs, focus group discussions with FCHVs, and members of Mothers’ Groups for Health. Most Significant Change stories were collected from FCHVs, in-depth interviews with stakeholders, and service statistics. Results show that the FCHVs’ knowledge increased, attitudes changed, and confidence in addressing GBV grew. During the study period, FCHVs identified 1,253 GBV survivors and referred 221 of them to health facilities. In addition to assisting GBV survivors, FCHVs worked to prevent GBV by mediating conflicts and curbing harmful practices such as menstrual isolation. Stakeholders viewed FCHVs as a sustainable resource for identifying and referring GBV survivors to services, while women trusted them and looked to them for help. Results show that, with proper training and safety mechanisms, FCHVs can raise community awareness about GBV, facilitate support for survivors, and potentially help prevent harmful practices.

Background

Gender-based violence (GBV) is widespread globally and has numerous adverse health effects (Palmero et al., Citation2014). Global estimates suggest that one in three women (35%) worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner at some point in their lives (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2013a). In Nepal, more than one in five women have ever experienced physical violence since age 15, and 26% of women have experienced spousal violence by their current or most recent husband (Ministry of Health and Population [MoHP] et al., Citation2017). Although women who experience violence at home generally turn to friends or family for help, international research has consistently found that abused women use health care services for a constellation of complaints more often than non-abused women do, even if they do not disclose the violence or abuse (Bonomi et al., Citation2009). These interactions with health care providers offer a promising opportunity to reach out to survivors of GBV.

The Government of Nepal has been working to improve health services for GBV over the past decade, notably by establishing 55 one-stop crisis management centres (OCMCs) that provide multisectoral services for GBV survivors, including health care, psychosocial counselling, access to safe homes, legal protection, personal security, and vocational training. However, awareness and utilisation of these services remains low, nationally, only one in five Nepali women who have experienced violence sought help from anyone (MoHP et al., Citation2013; Government of Nepal, Citation2017). In 2016, a national workshop in Nepal to review OCMCs pointed out that female community health volunteers (FCHVs) were uniquely positioned to create awareness about GBV and available services (Nepal Health Sector Support Programme, Citation2016). FCHVs are trusted members of the community who have promoted positive behaviours related to safe motherhood, child health, family planning, and other community health concerns in all 77 districts of Nepal since 1988 (Ministry of Health and Population, Citation2019). As part of their role, they conduct household visits, provide counseling and referrals on maternal and child health, and work with community-based Mothers’ Groups for Health. Mothers’ Groups, each of which consists of 12–15 women, are active in various social and economic activities in the community and meet at least monthly to learn about diverse health topics from the FCHV.

Globally, there is growing, but still limited, peer-reviewed research on the role of community health workers (CHWs) or volunteers in responding to GBV. CHWs have expressed concerns about getting involved, including challenges in identifying and assessing GBV cases; not knowing how best to respond; not knowing how to initiate conversations about GBV, frustration and stress, and safety concerns (Davies et al., Citation1996; Eddy et al., Citation2008; Ved et al., Citation2019). In Nepal, a common concern is that FCHVs may be overwhelmed by the number of programmes that have called on them to participate (Khatri et al., Citation2017), and the global literature confirms that too many responsibilities may reduce CHW productivity and service quality (Jaskiewicz & Tulenko, Citation2012).

However, research from settings as varied as Brazil, Burma, and India has characterised CHWs as trusted members of the community to whom GBV survivors may more readily disclose violence and the need for help (Sarin & Lunsford, Citation2017; Signorelli et al., Citation2018; Ved et al., Citation2019). In Pakistan, GBV survivors experienced positive benefits from group counselling facilitated by CHWs who attended a short training on basic counselling skills (Karmaliani et al., Citation2012). However, a systematic review by Gatuguta and colleagues (Citation2017) focusing on whether CHWs should offer health services to survivors of sexual violence found that evidence was scanty and of uncertain quality. More recently, two randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that CHWs can play an effective role in preventing intimate partner violence through community sensitisation and facilitating access to services. In Ghana, physical violence reported by women decreased in communities where community-based action teams led dialogues at local events on women’s economic rights, equitable household practices, and non-violence and also counselled couples (Ogum Alangea et al., Citation2020). In the United States, study areas showed significant, sustained decreases in intimate partner violence in response to home visits to pregnant women during which a CHW or nurse reviewed information on the cycle of violence, danger assessments, safety planning, and available resources (Sharps et al., Citation2016).

This study in Nepal sought to gather evidence on the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a programme to orient FCHVs on how to identify and refer GBV survivors to facility-based health services. Findings from this one-year pilot programme in Mangalsen municipality will be used to inform government efforts to build the capacity of the health system in Nepal to respond to GBV.

Methods

Study setting

This pilot study was implemented in Mangalsen municipality, a town of around 32,500 people that is the capital of Achham District in western Nepal, and the location of the district’s hospital-based OCMC. In addition to the district hospital, there are seven health posts in the municipality; nine to 31 FCHVs work in the catchment area of each health post.

The intervention

With funding from Swiss Development Corporation and Norwegian Embassy, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in collaboration with Jhpiego, aimed to reduce GBV through prevention and response interventions. These integrated interventions included development of a national clinical protocol, strengthening of OCMCs and peripheral health facilities, capacity building of service providers, provision of medico-legal services and shelter homes, security and legal support, psychosocial counselling, and mental health rehabilitation. Despite the creation of a national clinical protocol on GBV in 2015 and corresponding competency-based training for health care providers in seven UNFPA-supported districts in Nepal, service uptake remained low. In response, Jhpiego and UNFPA developed a new strategy to orient FCHVs on how, as part of their routine work in the community, to identify GBV survivors and refer them to health facilities for management, treatment, psychosocial counselling, legal advice, and safe shelter.

In 2017, Jhpiego and UNFPA trained 35 in-charges, including doctors and nurses from the Accham district hospital, and auxiliary nurse midwives from seven government health posts on a newly developed pictorial GBV toolkit that covered types and causes of GBV, health effects, signs and symptoms of GBV, counselling and services, referrals, and the role of FCHVs in bridging the gap between the community and the health facility. The package was field-tested with 10 FCHVs in Okhaldunga District and the tools were assessed for clarity and understanding. In August 2017, the 35 trainers used the toolkit to conduct one-day orientations on GBV for all 116 FCHVs working in Mangalsen municipality, including on the importance of privacy and confidentiality and how to keep themselves safe and report adverse events while working with survivors. More specifically, FCHVs were oriented on how to identify the survivors during the orientation and were instructed to identify potential survivors of GBV during their routine home visits – weekly or any time, as required. They were oriented to discuss the health issues as per their routine work with the potential survivors separately from the family members, and to prepare dummy questions (health related) if any of the family members raises concerns. FCHVs were asked to inform the survivors of the services available in health facility and OCMC, provide contact information of those services, and refer them to the health facilities but not record anything on the spot. FCHVs were further instructed that they were forbidden to escort the survivors to health facilities or try to resolve the issue by themselves.

Following the orientation, FCHVs worked to identify and counsel GBV survivors during routine household visits and community meetings. FCHVs identified women and girls showing signs of unusual behaviours, including signs of depression, alcohol and drug abuse, bruises and wounds, or women and girls who reached out themselves for help and support. FCHVs contacted women and girls individually only when they suspected potential GBV. In addition, they delivered sessions on GBV to Mothers’ Groups and the community to inform them about types of GBV and the help and support survivors could receive from legal, health, and other services, and how to access facility-based services at health posts and the district OCMC, while maintaining privacy and confidentiality. Some survivors were also identified from these sessions as well during discussions. FCHVs met monthly at health posts to report on their activities and discuss challenges with one another and with health facility in-charges and district coordinators employed by Jhpiego.

Study design

We used parallel mixed methods (Teddlie & Tashakkori, Citation2008) to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of FCHVs’ involvement in the identification and referral of GBV survivors (see for a list of study participants and data collection activities). To qualitatively assess feasibility and acceptability, we conducted two baseline and two endline focus group discussions (FGDs) with FCHVs regarding their knowledge of GBV, their role in supporting GBV survivors and linking them to services, and barriers and facilitators to working with GBV survivors in the community. One baseline and one endline FGD were conducted with Mothers’ Group members on barriers to accessing GBV support and services. We also conducted key informant interviews at baseline and endline with one doctor and one nurse from the district hospital, two police officers, and a safe house counsellor to examine their perspectives on FCHV involvement in the health sector response to GBV.

Table 1. Data collection activities, participants, and timeline.

To quantitatively assess the effect of the intervention on FCHVs’ knowledge and attitudes, we conducted knowledge and attitudinal surveys of FCHVs at baseline, immediately after the one-day GBV orientation, at midline, and at endline. The survey consisted of four questions that represent key initial knowledge and attitudinal shifts that need to happen to move people to action on GBV; namely, what constitutes GBV, signs that a woman may be experiencing GBV, where GBV survivors should be referred, and the key principles of privacy and confidentiality when counselling GBV survivors. Some questions and responses were drawn from the Demographic and Health Survey Woman’s Status Module while others were based on common myths and misconceptions about GBV drawn from the global literature and programme experience on changing social norms around GBV. The survey used pictorials to offer multiple choice options to account for the low literacy of FCHVs.

To assess whether FCHV referrals increased the number of GBV survivors accessing facility-based services, we compiled data from GBV service registers maintained at each health facility. The registers included demographic characteristics of survivors, types of services received, and whether the referral source was an FCHV, an organisation, a self-referral, or a health worker.

To identify notable changes at the community level that were experienced or observed by FCHVs, we used a participatory qualitative evaluation method originally developed in 1994 by Rick Davies called Most Significant Change (Davies & Dart, Citation2005). FCHVs were asked to share stories about their experiences identifying and linking GBV survivors to care during group discussions at monthly meetings at each health post. MSC story writers transcribed the stories and facilitated a monthly and quarterly selection process to identify the most important stories.

Sampling

Key informant interview (KII) participants were recruited purposively based on their knowledge of the system for providing GBV services and the FCHV programme. For the FGDs with FCHVs, two FCHVs from each facility within the study area were randomly selected by the health facility in-charge using a lottery method. One FGD was conducted with FCHVs attached to four remote facilities, and the other FGD included FCHVs attached to facilities within a one-hour drive from the district hospital. Mothers’ Group members were also randomly selected by the health facility in-charge using a lottery method.

Data collection

FGDs and KIIs. Two independent research consultants with advanced degrees conducted all KIIs and FGDs to provide a fresh and unbiased perspective. They used KII and FGD checklists prepared by the principal investigator and the Jhpiego research team. All responses were audio-recorded and transcribed in Nepali and then subsequently translated by the research team.

Referrals and health service utilisation. FCHVs tracked GBV survivors they identified and referred on tally forms. Health facility in-charges compiled data from these tally forms during monthly meetings and entered the information into a database.

Separately, service statistics on visits by GBV survivors to health facilities were collected monthly from GBV registers at each facility. Information on demographic characteristics, type of violence experienced, services received, and referral pathways of survivors were retrieved from GBV registers and analysed.

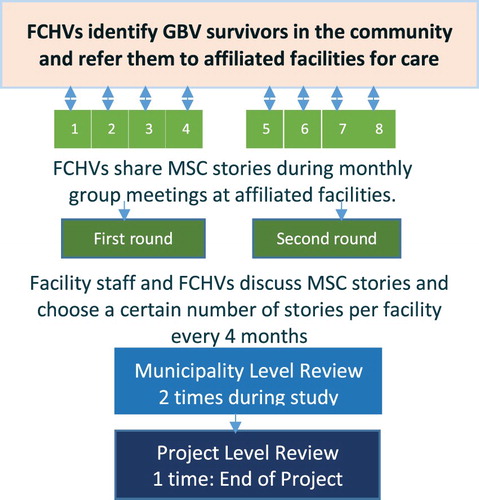

Most Significant Change (MSC). During monthly meetings at each health post, FCHVs shared stories and voted for two to be MSC stories; these were recorded by the health facility in-charge and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs). The stories were winnowed down during further rounds of selection, initially at the facility level and later at the municipal and project levels; this process resulted in six MSC stories at the end of the study (). As part of the MSC orientation, programme staff and FCHVs were encouraged to consider negative changes as well as positive changes when developing stories, as negative changes can provide important insights for programme improvement and to ensure that the programme does no harm. However, none of the stories from FCHVs included negative changes. After the MSC stories became repetitive, indicating saturation of the qualitative data, an institutional review board protocol amendment was submitted and approved to discontinue the final round of MSC story collection to save resources.

Data analysis

Mean scores of FCHVs on the knowledge assessment before the orientation, immediately following the orientation, six-months post-orientation, and one year after the orientation were calculated and compared. Competency of the FCHV was defined as 80% scores, which is the minimum competency score for all health topics in Nepal’s national system for health trainings, including the national competency-based training package on GBV for health workers. Data were analysed using SPSS version 25.

Data recorded by FCHVs in tally books on GBV cases were compared to GBV registers in health facilities to verify which GBV survivors that FCHVs referred actually accessed services at a health facility. Service statistics for GBV services at health facilities were analysed using SPSS version 25.

Two sets of researchers (an independent researcher and a co-researcher) were responsible for data collection and verbatim transcription and translation during both baseline and endline study, respectively. The qualitative study followed consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., Citation2007). Data analysis was done manually through thematic analysis in Word for the baseline while Dedoose software version 8.0.42 was used for the endline. In both instances, the audio records and field notes of all interviews were taken in Nepali language, which were then translated into English language during the process of transcription and annotated into a Word document. The transcripts were read and re-read by the independent researchers to identify the patterns and the key excerpts. For the endline study, the Word files of transcriptions were also uploaded to the Dedoose software for coding. The researcher identified categories from the coding of the transcripts, which were then organised into major themes based on the research question. In both instances, the preliminary subthemes were discussed and shared with the research team to put into the final themes to represent the overall objectives of the study.

The MSC process was designed to document changes within the FCHVs and their communities from the perspective of the FCHVs themselves. In the first round of review, FCHVs used their own experiences and personal criteria to evaluate the stories shared by their colleagues and select two most significant stories. The MSC stories were read out loud and discussed in groups. The participants were given the options for open or closed voting; or choosing the most significant story via discussion. Except for two stories in the entire MSC process, there were no disagreements among participants in selecting the most significant change. The stories were chosen by ultimately arriving at a consensus on which represented the most significant change. After the selection, a facilitated discussion examined the reasons for choosing the selected stories; in all but two cases, FCHVs unanimously agreed on the selected stories based on the strength of the change detailed in the stories. In the remaining cases, consensus was not reached and FCHVs cast votes to make their final selections. Later rounds of review divided the stories into domains of change that were defined by the FCHVs. At the end of the study period, the project team translated the stories into English and conducted a secondary analysis using Dedoose software version 23. Additional analysis explored how story themes, domains, or criteria for story evaluation evolved over the life of the project.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the guidelines of the World Health Organization (Citation2001, Citation2016) for research on violence against women to ensure the safety and confidentiality of study participants and mitigate possible distress. Ethical approval was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council (study number 295/2018) and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (study number 8571) institutional review boards. In Mangalsen municipality, approval for conducting the study was given by the health office and the municipality office. Health coordinators representing the municipality and focal persons from the district health office participated in the study during GBV orientation, MSC methodology orientation, monitoring of activities, and MSC story selection. The trained health facility in-charges were tasked with notifying FCHVs about the GBV orientation and making clear that FCHV participation was voluntary. Verbal consent was obtained from all FCHVs to participate in the intervention study. We anticipated that some FCHVs could be survivors of GBV themselves; hence, they were given the option to opt out of participating in the intervention. However, all FCHVs gave their consent to participate. Written consent was obtained from the respondents to baseline and endline FGDs and KIIs.

Results

Characteristics of FHCVs

The 116 FCHVs were a diverse group, ranging in age from 29 to 53 years, with 4 to 22 years of experience as an FCHV. Most FCHVs could read and write and had formal education between grades 8 and 10. During the course of FGD, some of the FCHVs shared that they were survivors of GBV themselves.

Knowledge and attitudes of FCHVs

The orientation on the GBV toolkit improved FCHVs’ understanding and attitudes regarding GBV and empowered them to advocate for change in the community. In their own words:

Before, we had no training. We did not understand much either. We did not know what GBV is. How would we have known that chaupadi [menstrual isolation] is a form of GBV too? (FCHV 8/FGD 3)

Average scores on the knowledge assessments increased from 71% correct at baseline to more than 97% with all correct scores at endline. There was also a shift in attitudes. During the pre-test, 51% of FCHVs agreed that ‘GBV is a private matter; outsiders should not intervene'; by the end of the study that figure decreased to 7%. Likewise, the proportion of FCHVs who agreed that ‘a husband is justified in beating his wife under certain conditions’ fell from 44% to 4%.

During endline FGDs, FGHVs acknowledged improvements in their knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in addressing GBV and credited the intervention. For example, one FCHV explained that:

People used to think that just hitting and killing is violence … we too thought the same, so how would others know. Later after this training, we came to realize that those little things behind were also violence. Fight between husband-wife is a violence too … Little did we know that sending daughters to cowshed is a violence too … (FCHV 7, FGD 3)

Another FCHV shared how the intervention empowered FCHVs:

Since the GBV program has been implemented, there’s been big changes. … let’s say our courage has increased … we can speak … we are not scared of [threats] … we can work without worrying. (FCHV 4/FGD 1)

At baseline, FCHVs were not clear about referral pathways. At endline, they identified the health facility/OCMC as the place where they should refer GBV survivors, per guidance received during orientation. Despite this knowledge, however, some FCHVs mentioned referring survivors directly to a safe house, the police, or the municipality office rather than a health facility, based on the survivor’s needs.

Some of the FCHVs shared their personal experiences of violence during the baseline FGDs and expressed concerns about potential threats they might receive while working with survivors. Although no severe adverse events were reported during the project, some FCHVs did describe receiving verbal resistance from perpetrators:

Why do you bother, it’s not your headache. It’s between husband and wife. Why do you have to come in the middle? Disagreements are like fire and water; we fight we patch up. What’s your problem? (FCHV 5/FGD 1)

Cases were resolved with support from the community through Mothers’ Group meetings, which FCHVs facilitate, and the ward office. Meeting members, including ward leaders, social workers, Mothers’ Group members and representatives from local welfare groups, listened to arguments of both parties and discussed their concerns. The cases were resolved by issuing a written mutual agreement signed by the two parties and warning the perpetrator of future legal consequences upon repetition of such behaviour.

Stakeholders’ and women’s perspectives

Stakeholders viewed FCHVs as a sustainable workforce for the identification and referral of GBV cases to formal services. The medical officer said:

It is good to make a program related to GBV sustainable, and it requires a workforce on a regular basis. FCHVs will always be there [within the community]; in that case I feel that this program will last for a long time. (Service provider district hospital/KII)

Members of Mothers’ Groups expressed positive perceptions of FCHVs, identifying them as providers that women trust and look to for help. They also saw them as important information sources. As one explained: ‘The more new things they [FCHVs] learn, we get to learn about it too'. Mother Group 5/FGD 2.

However, stakeholders considered the older age and illiteracy of some FCHVs to be potential barriers to performing their role effectively.

Health service utilisation by GBV survivors

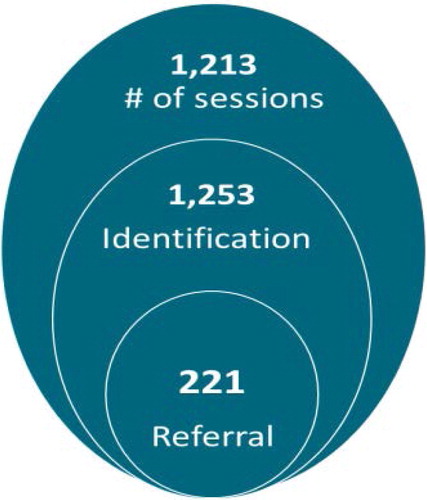

During the study period, 116 trained FCHVs conducted 1,213 sessions on GBV with Mothers’ Groups and at community gatherings, reaching more than 2,000 women. On average, each Mothers’ Group held 10 sessions (range: 8–12) on GBV throughout the study period. FCHVs identified 1,253 GBV survivors during their routine work and reported referring 221 of them to health facilities for further services ().

The number of GBV survivors visiting health facilities – regardless of referral source – rose to 251 during the study period (August 2018 to July 2019) from 81 the year before (July 2017 to June 2018). Of the 251 GBV cases during the study period, 22 (9%) were listed as FCHV referrals in facility records. Of these 22, all were female, 36% reported psychological and emotional abuse, and 36% reported physical assault. Although relatively few GBV cases were identified as FCHV referrals, key informants felt that the community activities of the FCHVs – especially the discussion sessions in the Mothers’ Group meetings – contributed to the sharp increase in GBV visits to health facilities. Half of the GBV cases seen at study facilities during the duration of the project were listed as ‘self-referred' or ‘health worker-identified', and it is possible that FCHV activities prompted some of these visits.

During the endline FGDs, FCHVs offered several hypotheses regarding why the number of GBV referrals they made to health facilities might be lower than expected, given the number of cases they identified. However, the study was not designed to be able to follow-up with GBV survivors that did not access health services when referred by FCHVs. Still, FCHVs cited a number of reasons that survivors may not have accessed services. They acknowledged first trying to resolve issues within the community and only referring GBV survivors to health facilities when they considered the situation to be more serious:

Like when there is injury, there’s a lot of mental problems. When our counselling doesn’t work, we send them to health facility in those situations. (FCHV 8/FGD 1)

In addition, FCHVs sometimes referred women to sites other than health facilities to meet women’s immediate needs, for example, for legal assistance or protection:

They need an immediate place to stay … they come to us suffering … If we take them to health facilities and if they are sent back home immediately after the treatment, she might go through more problems … so we need to take them to safe house too. (FCHV 8/FGD 3)

Finally, some survivors do not act on referrals to a health facility for fear that it will escalate the violence. As most perpetrators come from the family and/or community, survivors fear retaliation for breach of confidentiality in the form of more beatings or being separated from their children:

The fear that she wouldn’t be allowed to stay with her children, the husband might say –‘what were you thinking that you’d get? And look what you got!’ (FCHV 6/FGD 1)

Most significant changes

A total of 267 MSC stories were collected during the project; 9% were related to changes in knowledge, 21% to changes in attitude, and 70% to changes in behaviour. These stories show that FCHVs went beyond raising awareness and making referrals to play a more active role in addressing GBV. FCHVs also worked to transform community attitudes toward harmful practices, mediate conflicts, and mitigate drivers of violence, like alcoholism. Although these activities were outside the scope of what was asked of them, FCHVs perceived that the most significant changes came about as a result of their work as change agents, encouraging individuals, families, and entire communities to stop violent or harmful practices. MSC stories also highlighted changes in the FCHVs’ themselves, largely related to beliefs and practices around menstrual isolation.

The final six MSC stories – selected by consensus – illustrate what FCHVs consider the most significant changes resulting from the project. Two stories demonstrate how the GBV orientation empowered FCHVs to advocate for community-wide changes in attitudes and behaviours related to harmful practices like forcing women to seclude themselves in a chhaugoth (menstrual hut) during menstruation. In one story, the FCHV described how she led repeated discussions of this issue during meetings of the Mothers’ Group until they recognised the dangers and concluded ‘we need to unite and declare this area as shed (chhaugoth) free’. The other story recounts how a FCHV was motivated to take action personally and then became a role model for the community:

… I used to stay in chhaugoth during menstruation. After orientation on GBV toolkit, I understood that it is not safe to stay in chhaugoth, and it is one of the types of GBV. This touched my heart, so I built a room near my house and started to stay in that room instead of staying in chhaugoth … Later five or six people also demolished their chhaugoth and built similar room in their house … Now the trend of avoiding menstrual sheds during menstruation is increasing. (FCHV, Mangalsen)

Two other MSC stories describe how FCHVs led multisectoral efforts to address the cultural practice of child marriage. After a 17-year-old girl eloped of her own accord, the FCHV joined with members of the Mothers’ Group to convince her husband’s family to return the girl to her mother’s home to continue her studies. In the second story, the FCHV engaged community leaders to address child marriage:

A man tried to forcefully marry a girl aged 14 years old … He tried to put Sindoor [red color, symbol of marriage] on the girl’s forehead. The girl shouted in fear and succeed in escaping from a window and went directly to her home, crying. She explained the incident to her parents … I also knew about the incident, so along with the girl and her family I went to the municipality. The mayor asked me [the FCHV] to take the case to the local ward office … I called the man and gathered community people, Mothers’ Group, and discussed the incident. The community declared the man a culprit … The man asked for forgiveness and is willing to accept punishment by law if he ever repeats … (FCHV, Bannatoli)

Another MSC story describes how a FCHV joined with a Mothers’ Group to tackle alcohol-related violence by establishing a system of fines for those who drink to excess and for shopkeepers who sell alcohol beyond the allowed time. According to the story:

… the Mother’s Group fined NRs 3,000 each of the three persons who were drunk and causing disputes. They deposited it in Mothers’ Group fund that will be used for women’s empowerment. Once everyone saw them getting charged, fear of fine and legal consequences, others have also started to avoid alcohol … (FCHV, Kalagau)

FCHVs engaged in identifying psychological abuse in the community and restoring peace in the family:

… one day, I [FCHV] saw her taking shower with her clothes on. I asked her, what she was doing. She replied, ‘Nobody loves me, I don’t have house to stay, nobody gives me food and my family members don’t even support me’. Feeling pity upon her, I took her home … the woman’s in-laws knew about me supporting her. They came to my house and started arguing … I took the woman to OCMC and was further referred to safe house. Currently, she is at safe house and improving. (FCHV, Mangalsen)

Discussion

This study found that FCHVs in Nepal are capable, willing, and motivated to raise awareness about GBV in their communities and help survivors. Due to their longstanding roles as health promoters as well as their participation in this intervention, FCHVs were viewed as powerful change agents in the community. Community members and leaders viewed them as individuals that women can trust to speak to about their GBV experiences. These overall findings are consistent with research and documentation, albeit limited, from other countries that CHWs can play a positive role in responding to GBV (Gatuguta et al., Citation2017; National Health Systems Resource Centre, Citation2011).

The work of the FCHVs contributed to a threefold increase in the number of GBV survivors reaching health facilities. In addition, FCHVs referred some GBV survivors to other sources of support to meet their expressed needs, including safe houses, municipal authorities, and the police. In still other cases, they were able to mediate solutions in the community, thus avoiding referrals altogether. While their efforts sometimes contradicted the guidance issued during the GBV orientation, which limited their role to health facility referrals, they reflect a survivor-centred approach that has been widely adopted internationally. In a survivor-centred approach to GBV, a survivor’s wishes are supposed to determine the care offered, in recognition that she is the most expert regarding her own needs (WHO, Citation2013b) This may mean that a woman decides not to access services or report GBV or that she seeks services that are outside the scope of what the health sector offers. The study team and Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population originally wanted to limit referrals from FCHVs to health facilities because FCHVs are part of the health system. As the experience of this pilot project demonstrates, however, GBV must be recognised as a multisectoral issue and survivors’ wishes should be prioritised. Therefore, any future work on involving FCHVs in responding to GBV should orient FCHVs to the full range of services available to GBV survivors and include guidelines on maintaining a survivor-centred approach that respects survivors’ wishes, privacy, and confidentiality at all times.

The expanded role assumed by FCHVs should be carefully considered and clearly delineated before scaling up the deployment of FCHVs to address GBV. Some FCHVs reported receiving verbal threats from GBV perpetrators when trying to assist survivors. Ultimately, these cases were resolved, sometimes through the support of the wider community. However, safety concerns of FCHVs should be paramount, and clear protocols are needed on what to do in case of threats or retaliation by perpetrators. Safety measures implemented for ASHAs (accredited social health activists), India’s equivalent of FCHVs, may be worth replicating. These include overnight rest rooms for ASHAs who accompany patients, monthly staff meetings that include discussion on sexual harassment, intervention by higher-level staff where threats or harassment are reported, and grievance and redress mechanisms (Ved et al., Citation2019).

MediationFootnote1 or intervention by FCHVs may not only lead to increased risk of harm for themselves, but may also increase the risk that survivors do not access formal services or get justice. While there is some evidence that formal mediation by local authorities and community bodies, such as the victim/offender programme in South Africa (Heise, Citation2011) and the Sajhedari Bikaas Project in Nepal (McGrew, Citation2013), have benefited survivors by letting their voices be heard, there are concerns that mediation – especially if conducted by non-trained individuals through informal processes, as is the case with FCHVs – may lead to survivors not receiving due justice and being coerced back into violent situations (Heise, Citation2011). Even where mediation has been recognised as a means for accessing justice, where formally studied, the legal system remains the preferred way for GBV survivors to obtain justice, such as compensation or punishment of the perpetrator (Scott et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, basic counselling skills, including active listening and social support, are an important first-line support that CHWs can provide (WHO, Citation2013b, Citation2014). Thus, future interventions should establish protocols that clearly delineate parameters for the FCHVs role in intervening in GBV cases (namely, that any conflict resolution they attempt should always be accompanied by information about the law and the rights of survivors as well as available services), while also providing additional training to enable FCHVs to adequately play this role.

Based on this experience in Mangalsen municipality, the most significant role FCHVs can play in addressing GBV at the community level appears to fall more along the lines of prevention than response. Stories of FCHVs leading their communities to abandon menstrual isolation, impose fines on excessive alcohol use, and not marry off their daughters early clearly demonstrate the role that FCHVs can play as agents of change. Similar findings on the positive role community health workers and volunteers can play in preventing GBV have been documented in other settings (Gatuguta et al., Citation2017; Ved et al., Citation2019). Further capacity building on gender transformative dialogues and community mobilisation can enhance this work. Studies in Ghana and the United States have demonstrated the effectiveness of interventions to reduce intimate partner violence by raising awareness about violence, counselling couples experiencing violence, conducting safety planning, and providing referrals (Ogum Alangea et al., Citation2020; Sarin & Lunsford, Citation2017). However, these interventions involved considerable investments in training and support and raise concerns about overburdening FCHVs with too many responsibilities. Further research on feasibility is needed before formalising the role of FCHVs to mobilise communities against GBV in Nepal.

The study contributes to the growing body of evidence that community engagement is an important dimension of a health system response to violence against women (Colombini et al., Citation2019; García-Moreno et al., Citation2015). In settings where there is strong stigma attached to women speaking out against the abuser because of the shame it brings to their family, community engagement through CHWs, for example, the FCHVs in Nepal, can strengthen the health system response to violence against women.

Limitations

Despite being a small-scale pilot, this study provides important insights into the potential role of FCHVs in addressing GBV in Nepal and similar low-resource settings and valuable information for the design of future interventions. However, we must acknowledge some important limitations, notably regarding the small number and lack of diversity of participants. Due to limited resources, only one focus group was conducted with Mothers’ Groups, so the study lacked the perspective of other important elements of the community, such as younger women, men, and mothers-in-law, and perhaps most significantly, the actual survivors who were referred or supported by FCHVs. We posited that some of the Mothers’ Group members participating in the FGDs were likely survivors of violence. However, without specifically selecting GBV survivors due to ethical and privacy considerations, we could not probe specifically about their perspectives. Likewise, we conducted FGDs with just two groups of FCHVs. Responses varied between the two groups, and information did not quite reach the point of saturation with respect to perspectives on challenges or opportunities relating to their role in responding to GBV. Another important limitation was the fact that our study only tracked referrals to health facilities, while FCHVs also referred survivors to other sources of support. Finally, the study took place in just one municipality and therefore, may not be generalisable to other provinces in Nepal.

Conclusions

This pilot study found that involving FCHVs in the response to GBV through awareness raising, counselling, and referral to services is feasible and acceptable from the perspective of FCHVs and stakeholders involved in the GBV response in Mangalsen. Scale-up is warranted in other districts of Nepal with careful monitoring and adaptation according to cultural variations in those contexts, given that the intervention was piloted in just one district, as well as institution of systems to maximise safety for FCHVs and survivors reporting cases. There is a promising role for FCHVs to play in preventing GBV through social change interventions, but further studies are needed that involve adequate training and tracking of the acceptability and effectiveness of FCHVs playing this role formally.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the coordinators of the study at the district level, Surya Prasad Poudyal and Ramesh Thapa. We also appreciated the work of Hannah Tappis and Adrienne Kols who reviewed manuscript drafts and provided invaluable feedback to strengthen the manuscript. Finally, we are grateful to all the study participants, in particular the FCHVs of Mangalsen. MB, AS, RA, KT, and EAP conceptualised the study design. All authors contributed to the design of the study tools. AT and MTC conducted the literature search. MB analysed literature. AT conducted the data extraction. PR collected and analysed the baseline qualitative data. RD collected and analysed the endline qualitative data. AT, EAP, MB, KT, and MTC contributed to data analysis and interpretation. MB and AT led the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, MB. The data are not publicly available as it contains personal quotes from the key informant interviewees, which may be identifiable.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Mediation is defined as a voluntary, confidential, informal, non-binding process whereby an impartial third party/parties (mediator(s)) help those involved in a dispute to resolve it, by helping them to reach their own agreed-upon resolution. The goal is for the parties to come up with a win-win solution, to save time and money by avoiding costly, lengthy court procedures. Mediation is not the same as giving advice, punishment, or counseling.

References

- Bonomi, A. E., Anderson, M. L., Rivara, F. P., & Thompson, R. S. (2009). Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research, 44(3), 1052–1067. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x

- Colombini, M., Alkaiyat, A., Shaheen, A., García-Moreno, C., Feder, G., & Bacchus, L. J. (2019). Exploring health system readiness for adopting interventions to address intimate partner violence: A case study from the occupied Palestinian Territory. Health Policy and Planning, 35(3), 245–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz151

- Davies, R., & Dart, J. (2005). The ‘most significant change’ (MSC) technique: A guide to its use. Care International.

- Davies, J., Harris, M., Roberts, G., Mannion, J., McCosker, H., & Anderson, D. (1996). Community health workers’ response to violence against women. Australian New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 5(1), 20–31.

- Eddy, T., Kilburn, E., Chang, C., Bullock, L., & Sharps, P. (2008). Facilitators and barriers for implementing home visit interventions to address intimate partner violence: Town and gown partnerships. Nursing Clinics of North America, 43(3), 419–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2008.04.005

- García-Moreno, C., Hegarty, K., D’Oliveira, A. F. L., Koziol-McLain, J., Colombini, M., & Feder, G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 5(9977), 1567–1579. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7

- Gatuguta, A., Katusiime, B., Seeley, J., Colombini, M., Mwanzo, I., & Devries, K. (2017). Should community health workers offer support healthcare services to survivors of sexual violence? A systematic review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 17(1), 28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-017-0137-z

- Government of Nepal. (2012). A study on gender-based violence conducted in selected rural districts of Nepal.

- Heise, L. L. (2011). What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. STRIVE Research Consortium.

- Jaskiewicz, W., & Tulenko, K. (2012). Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: A review of the influence of the work environment. Human Resources for Health, 10(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-10-38

- Karmaliani, R., Pasha, A., Hirani, S., Somani, R., Hirani, S., Asad, N., Cassum, L., & McFarlane, J. (2012). Violence against women in Pakistan: Contributing factors and new interventions. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(12), 820–826. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.718046

- Khatri, R. B., Mishra, S. R., & Khanal, V. (2017). Female community health volunteers in community-based health programs of Nepal: Future perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00181

- McGrew, L. (2013). The role of community mediation in addressing gender-based violence: Assessment and recommendations on the role of community mediation in addressing gender-based violence in Sajhedari Bikaas project districts in Nepal’s Far-West and Mid-West regions. United States Agency for International Development.

- Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal. (2019). Annual report of department of health services 2074/75 (2017/2018).

- Ministry of Health and Population, United Nations Population Fund, & Nepal Health Sector Support Programme. (2013). Assessment of the performance of hospital-based one stop crisis management centres.

- Ministry of Health, Nepal; New ERA; and ICF. (2017). Nepal demographic and health survey 2016.

- National Health Systems Resource Centre. (2011). ASHA: Which way forward? Evaluation of the ASHA Programme.

- Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP). (2016). Innovative good practices in Nepal’s health sector: 3. Hospital-Based One-Stop Crisis Management Centres (Pulse Report). Nepal Health Sector Support Programme.

- Ogum Alangea, D., Addo-Lartey, A. A., Chirwa, E. D., Sikweyiya, Y., Coker-Appiah, D., Jewkes, R., & Adanu, R. M. K. (2020). Evaluation of the rural response system intervention to prevent violence against women: Findings from a community-randomised controlled trial in the Central Region of Ghana. Global Health Action, 13(1), 1711336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1711336

- Palmero, T., Bleck, J., & Peterman, A. (2014). Tip of the iceberg: Reporting and gender-based violence in developing countries. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179(5), 602–612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt295

- Sarin, E., & Lunsford, S. S. (2017). How female community health workers navigate work challenges and why there are still gaps in their performance: A look at female community health workers in maternal and child health in two Indian districts through a reciprocal determinism framework. Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0222-3

- Scott, J., Polak, S., Kisielewski, M., McGraw-Gross, M., Johnson, K., Hendrickson, M., & Lawry, L. (2013). A mixed-methods assessment of sexual and gender-based violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo to inform national and international strategy implementation. International Journal of Health Planning & Management, 28, 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2144

- Sharps, P. W., Bullock, L. F., Campbell, J. C., Alhusen, J. L., Ghazarian, S. R., Bhandari, S. S., & Schminkey, D. L. (2016). Domestic violence enhanced perinatal home visits: The DOVE randomized clinical trial. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmont), 25(11), 1129–1138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5547

- Signorelli, M. C., Taft, A., & Pereira, P. P. G. (2018). Domestic violence against women, public policies and community health workers in Brazilian Primary Health Care. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 23(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018231.16562015

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (Eds.). (2008). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage Publications.

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32- item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Healthcare, 19, 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Ved, R., Scott, K., Gupta, G., Ummer, O., Singh, S., Srivastava, A., & George, A. S. (2019). How are gender inequalities facing India's one million ASHAs being addressed? Policy origins and adaptations for the world's largest all-female community health worker programme. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0338-0

- World Health Organization. (2001). Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women.

- World Health Organization. (2013a). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence.

- World Health Organization. (2013b). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines.

- World Health Organization. (2014). Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence: A clinical handbook.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Ethical and safety recommendations for intervention research on violence against women.