ABSTRACT

The genesis of the concept of intersectionality was a call to dismantle interlocking systems of oppression – racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class-based – in order to realise liberation of Black women and other women of colour. Intersectionality holds the radical potential to amplify collective efficacy, community solidarity, and liberation. The extension of intersectionality into stigma research has resulted in an increased focus on intersectional stigma in quantitative research. This raises questions regarding how the radical and liberatory potential of intersectionality is applied in stigma research. Specifically, empowerment-based perspectives may be overlooked in quantitative intersectional stigma research. We conducted a scoping review to document if and how empowerment-based perspectives were included in intersectional stigma quantitative studies. We identified and included 32 studies in this review that examined varied stigmas, most commonly related to race, gender, HIV and sexual orientation. In total 13/32 (40.6%) of these studies reported on empowerment-based factors; most of these examined social support and/or resilience. Taken together, findings suggest that the quantitative intersectional stigma research field would benefit from expansion of concepts studied to include activism and solidarity, as well as methodological approaches to identify the protective roles of empowerment-based factors to inform health and social justice-related programmes and policy.

Introduction

Merely naming the pejorative stereotypes attributed to Black women (e.g. mammy, matriarch, Sapphire, whore, bulldagger), let alone cataloguing the cruel, often murderous, treatment we receive, indicates how little value has been placed upon our lives during four centuries of bondage in the Western hemisphere. We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation is us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and our work. (Combahee River Collective, Citation1977)

There has been an evolution in stigma research over the last half century, from one rooted in Goffman’s (Citation1963) conceptualisation of social processes that oppress persons associated with the moral, disabled or racialized ‘other’, towards social psychological perspectives focused on the health impacts of stigma (e.g. Meyer, Citation1995), to structural analyses of the ways in which stigma (re)produces social inequities grounded in class, race, gender, and sexual dominance and oppression (Parker & Aggleton, Citation2003). Stigma is conceptualised as multi-level, spanning intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, legal and other institutionalised processes. There are expansive literatures documenting stigma pertaining to particular groups and communities, including individual and structural racism, sex work stigma, sexual stigma, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT)-related stigma, among others. There are also bodies of literature examining health-specific stigma, particularly regarding mental health and HIV. Interest in, and application of, intersectionality as an approach to assess multiple stigmatised identities is becoming more prevalent in stigma research (e.g. Logie et al., Citation2011; Stangl et al., Citation2019; Turan et al., Citation2019). Intersectional stigma refers to the ‘interdependent and mutually constitutive relationship between social identities and structural inequities’ (pg. 9; Logie et al., Citation2011). Converging experiences of stigma may target social identities (e.g. race, gender and class), practices (e.g. drug use, sex work), and/or health statuses (e.g. HIV serostatus) of individuals, groups and communities. Intersectional stigma occurs across social ecological levels, spanning intrapersonal, interpersonal, community and institutional dimensions; across these same dimensions, people can strive for positive change, exhibit coping, acquire support, and challenge stigma (e.g. Baral et al., Citation2013; Logie et al., Citation2011; Turan et al., Citation2019).

The resonance of intersectionality with a growing number of stigma scholars may be explained by sociology of science perspectives. As elegantly argued in ‘Intersectionality as Buzzword’ (Davis, Citation2008), it may in fact be intersectionality's ambiguity and lack of prescriptiveness pertaining to the methods that has enabled it to be taken up and applied to a range of research disciplines. While there is a growing body of quantitative intersectional stigma research, there is no consensus in the ways that intersectionality theory can be applied in its design, analysis, or interpretation (Logie et al., Citation2019; Turan et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, stigma researchers are currently engaging in myriad innovative approaches to integrating intersectionality into their quantitative studies.

The application of intersectionality theory to quantitative stigma research is rapidly growing, yet still nascent with regard to the development and integration of intersectional theoretical components, measurement, and methodologies (Turan et al., Citation2019). The increased visibility of intersectionality in the quantitative stigma field provides opportunities for advancing social justice and equity through focusing on the role of power in pathologizing stigmatised groups, and moving beyond a deficit-based perspective to amplify the agency of stigmatised groups in navigating systems of oppression via resilience, resistance and empowerment. Perhaps due to the emergent nature of quantitative intersectional stigma research there has been less attention to strengths in intersectional quantitative stigma research than in qualitative approaches (Turan et al., Citation2019).

This extension of intersectionality theory into stigma research raises questions regarding what and how intersectional perspectives are being applied to intersectional stigma research and what perspectives are missing. Stigma research has historically considered the ways by which persons understand, support one another, and navigate life and connections with others in the midst of stigma. For instance, Goffman (Citation1963) discussed managing the un/concealability of stigma, Meyer’s (Citation1995) minority stress model considered social support as a moderator between stigma and wellbeing, and Parker and Aggleton’s (Citation2003) discussion of power and dominance recommended that interventions focus on community mobilisation, social transformation, and resistance. These theoretical perspectives have helped to shift the focus from pathologizing stigmatised persons who experience health disparities to instead focus on the structural and social conditions that produce stress and reduce opportunities that in turn harm health outcomes (Earnshaw et al., Citation2013; Logie, Citation2012).

Stigma research often focuses on the harms of stigma to argue for social justice and equitable programmes and policies – yet when incorporating intersectionality theory, it is possible that researchers can lose sight of intersectionality's focus on strengths, resistance, and empowerment. Intersectional stigma has been conceptualised as creating the conditions for both marginalisation and opportunities across macro (advocacy), meso (social support and solidarity), and micro (resilience) levels (Logie et al., Citation2011). Other stigma researchers have proposed a multi-level stigma resilience agenda to build resources to mitigate health impacts of stigma (Earnshaw et al., Citation2013). For instance, structural level strategies can focus on empowerment via economic policy change, community education and mobilisation. Empowerment also includes nurturing pride and historical knowledge of stigmatised identities – such as among Black persons and/or LGBT persons – alongside socialising people with shared identities to recognise and navigate stigma (Earnshaw et al., Citation2013). At the interpersonal level, social support can help people impacted by stigma to reframe and make meaning of their experiences, engage in problem solving, and generate dialogue to process stigma experiences (Earnshaw et al., Citation2013).

These framings of people and their communities as more than vulnerable or passive recipients of stigma experiences reflect a nuanced perspective of power. For instance, Stangl et al.'s (Citation2019) Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework moves beyond a traditional conceptualisation of stigma ‘targets’ vs. ‘perpetrators’ to note the fluidity of power dynamics and the agency that persons have to navigate and effect change on their social contexts. Recognising that power is fluid and how persons enact relational, interpersonal and collective agency within contexts of structural inequities can challenge discourses of vulnerability (Ahmed, Citation2010; Logie & Daniel, Citation2016). It is key to move beyond a stigma=vulnerability focus; vulnerability framings are deficits-focused and can create false separations between persons and the environments they co-create, overlook social connections and relationships, and miss collective and community-based agency (Kippax et al., Citation2013).

The ways by which persons experiencing stigma navigate, mobilise, create communities of care, and resist stigma has been integrated in much qualitative intersectional stigma research. For instance, qualitative research studies have conceptualised intersectional stigma as inclusive of intrapersonal processes of resilience, interpersonal processes of solidarity and social support, and structural processes of resistance and challenging stigma (e.g. Holley et al., Citation2016; Levey & Pinsky, Citation2015; Logie et al., Citation2011; Rice et al., Citation2018).

There has not been the same level of integration of empowerment-based perspectives in intersectional stigma quantitative research (Turan et al., Citation2019). While there are contested definitions of empowerment (Cattaneo & Chapman, Citation2010), it can be understood as a non-linear, iterative and multi-level process that involves increasing ‘personal, interpersonal, or political power so that individuals, families, or communities can take action to improve their situations’ (p. 534; Gutiérrez et al., Citation1995). Multiple dimensions of empowerment include: intrapersonal, such as critical reflection, agency, self-efficacy and knowledge; interpersonal, for instance, negotiating and shifting power in relationship dynamics and acquiring social support; community, including collective agency and action; and institutional, transforming social and structural systems (Cattaneo & Chapman, Citation2010; Freire, Citation1972; Gutiérrez et al., Citation1995; Logie & Daniels, Citation2016). Whether empowerment perspectives are considered in intersectional research has theoretical and methodological implications. Merely naming and measuring ‘pejorative stereotypes’ could result in missing the lessons to be learned regarding how communities generate a ‘healthy love’ for self and others as discussed by the Combahee River Collective (Citation1977). Crenshaw (Citation1991), whose seminal work is referenced in intersectionality research, describes that researchers should not only focus on dominance but also on social empowerment associated with identities. Similarly, Davis (Citation2008) raises the same concerns as in the opening quotation by Combahee River Collective (Citation1977) regarding intersectionality's focus: ‘should it be deployed primarily for uncovering vulnerabilities or exclusions or should we be examining it as a resource, a source of empowerment’ (page 75)? In sum, applying strengths versus deficits perspectives reflects the power dynamics where researchers shape knowledge of intersectional stigma and health.

This manuscript aims to better understand the state of the quantitative intersectional stigma field. Specifically, we explored the quantitative intersectional stigma literature to understand to what extent empowerment-based aspects have been integrated and what strategies have been employed to apply empowerment-based perspectives. Synthesising this information can inform recommendations and strategies for intersectional stigma researchers to more effectively include empowerment-based perspectives in their research to align with the radical and liberatory potential of intersectionality.

Methods

The purpose of this study is to document empowerment-based perspectives included in research measures in quantitative stigma studies that identified intersectionality as a theoretical and/or methodological approach. To this end, we conducted a scoping review of the literature to identify quantitative studies that applied the concept of intersectionality across a broad range of disciplines to assess if and how empowerment-focused factors were included and how they were measured. Scoping reviews are a method that provides a broad overview of the literature to explore a general question to inform a higher level examination of a topic; while covering a broader conceptual range, they also go less in-depth into a particular literature than systematic reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). A scoping review also addresses theory and complex topics, thus is well suited for this investigation. We followed Arksey and O’Malley's framework for a scoping study, including: (a) identifying the research question (if and how have empowerment-perspectives been included in intersectional stigma research?); (b) identifying relevant studies; (c) selecting studies; (d) charting the data, and (e) summarising and reporting results (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

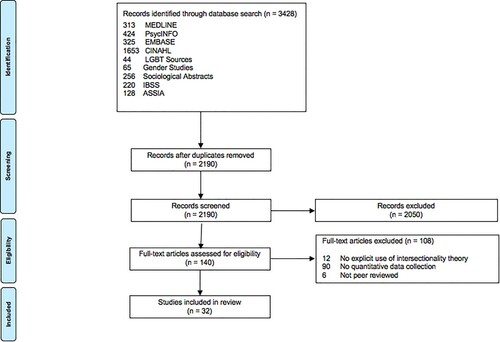

The search of English language peer-reviewed journal articles was conducted in September of 2020, and completed in consultation with an information specialist. We searched MEDLINE (313), EMBASE (325), PsycINFO (424), CINAHL (1653), LGBT Source (44), IBSS (International Bibliography of Social Sciences) (220), Gender Studies (65), Sociological Abstracts (256), and Applied Social Sciences and Index (ASSIA) (128). Search terms included (1) ‘intersectionality’ or related terms and (2) ‘social stigma’ and related terms (social stigma was a Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] term). For example, we searched intersectionality, intersection, intersecting, intersection* and stigma. The search was not time restricted.

References from this search were entered into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org), a systematic review web-based management platform, and underwent two stages of screening. First, references were screened by title and abstract by two team members with the following exclusion criteria: (a) not peer reviewed, (b) not assessing stigma, and (c) not using intersectionality theory. In the second stage, full text screening was completed by the same two team members with the following exclusion criteria: (a) not peer reviewed, (b) not a quantitative study, (c) not assessing more than one type of stigma or stigma and its intersection with health/social categories, and (d) authors not explicitly stating use of intersectionality theory in the background, methodology, or data analysis. We extracted key themes and findings pertaining to the ways in which empowerment-reated factors were (or were not) assessed.

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocols guideline (Tricco et al., Citation2018):

Population: This quantitative study review concerns studies that have examined stigma and applied an intersectional framework/approach to study design, theoretical framework, or analysis.

Intervention: Studies were included if they measure stigma and mention being informed/guided by an intersectional conceptual/theoretical approach.

Comparison or comparator: We included studies regardless of whether or not they included a comparison group. We only included quantitative studies, or mixed-methods studies with a quantitative component (and only included the quanitative data in the analysis).

Outcomes: We examined how studies report: (a) stigma, (b) intersectionality of stigma (what types of stigma or social categories are measured), and (c) empowerment perspectives associated with living, coping with, and/or managing stigma and/or marginalised identities (including but not limited to social support, solidarity, resilience, resistance).

Results

Our initial search resulted in 2122 references without duplicates. One hundred and forty references were then moved to the second, full-text screening stage and thirty two references were selected from this second stage for inclusion in this review. ().

The types of stigma measured in the 32 studies of focus in this review are varied. As detailed in , the five most commonly examined types of stigma were: race and racism (n=19); HIV serostatus and HIV-related stigma (n=17); sexual orientation and related stigma (n=15); sex, gender, gender identity and related stigma (n=13); and substance use and substance-use related stigma (including alcohol, smoking and general substance use) (n=5).

Table 1. Studies addressing intersectional stigma included in scoping review (n=32).

details the varied objectives that researchers applied in their intersectional stigma work. For instance, some examined combinations of devalued group identities with experiences of different types of stigma, including HIV-related stigma, sexual and gender orientation-related stigma, and mental illness stigma (e.g. Algarin et al., Citation2019; Bouris & Hill, Citation2017; DuPont-Reyes et al., Citation2020). Others examined multiple combinations of stigma on particular outcomes, such as race, class, gender and/or sexuality-related stigmas on healthcare barriers and health outcomes (e.g. Bastos et al., Citation2018; English et al., Citation2018; Logie et al., Citation2019). Many studies examined the ways in which different stigma types interacted with or exacerbated one another, such as HIV-related stigma and substance use stigma (e.g. Earnshaw et al., Citation2015), chronic pain stigma and HIV-related stigma (e.g. Goodin et al., Citation2018), racial discrimination and HIV-related stigma (Ion et al., Citation2017; Logie et al., Citation2016), and homelessness stigma and racial stigma (Weisz & Quinn, Citation2018). Some looked at specific social categories, such as race, gender, and socio-economic status, and if those influenced outcomes of racism (Haile et al., Citation2014), fat phobia (Makowoski et al., Citation2019), alcohol self-stigma (Moore et al., Citation2020), or sexual and gender minority stressors (Shangani et al., Citation2020). Together, approaches signal innovation and creativity in thinking through the various ways that social categories (e.g. race) intersect with social inequities (e.g. racism) with wide ranging health effects (e.g. mental health, physical health, healthcare engagement).

In we summarise the 13/32 (40.6%) quantitative intersectional studies that reported assessing any empowerment-based factors. Some studies examined associations between stigma and reduced levels of empowerment-based factors, while others examined if empowerment-based factors mediated or moderated the pathways from stigma(s) to wellbeing. Empowerment-based factors spanned intrapersonal (n=6 studies) (e.g. resilience), interpersonal (n=9 studies) (e.g. social support), community (n=2 studies) (e.g. LGBT connectedness), and institutional (n=3 studies) (e.g. women-centred healthcare, integrated substance use and HIV treatment) levels. Four studies looked at empowerment-based factors spanning more than one socio-ecological level.

Table 2. Quantitative intersectional stigma studies that included empowerment-based factors (n=13).

Intrapersonal resources were explored in different ways. For instance, positive intersectional experiences based on race or sexual orientation were associated with positive affect among Black sexual minorities, signalling the role that identity-related support plays in psychological wellbeing (Jackson et al., Citation2020). Self-esteem and mastery were associated with reduced depressive symptoms among men with physical disabilities (Brown, Citation2014). HIV-related stigma and sexual orientation stigma interacted to reduce psychological resilience among MSM living with HIV (Yang et al., Citation2020). These signal that resilience-related factors can promote wellbeing in stigmatising contexts, while also being depleted by the effects of stigma.

Social support was the most commonly studied interpersonal-level empowerment factor and was examined in a similar way, as a resource that could mitigate the harmful effects of stigma on wellbeing as well as be dimished by stigma. For instance, social support mediated the relationship between gender discrimination, HIV-related stigma, and mental health-related quality of life (Logie et al., Citation2018b). In another example with gender minority youth, positive maternal relationships were associated with positive sexual and mental health outcomes (Bouris & Hill, Citation2017). Others reported associations between HIV-related stigma and lower social support (e.g. Ion et al., Citation2017).

The two studies that explored community-level empowerment factors both assessed LGBT connectedness/inclusion but employed different approaches. The first did not find LGBT connectedness was associated with youth health outcomes (Bouris & Hill, Citation2017). The second found that Black MSM reported less racial inclusivity, and less positive affiliation, in the gay community than white MSM (Haile et al., Citation2014). Three studies examined institutional factors. For instance, a study reported women-centred HIV healthcare mediated the relationship between intersectional stigma and depression among women living with HIV (Logie et al., Citation2019). In another study, however, offering co-located HIV and substance use treatment with people living with HIV who used drugs did not reduce stigma, yet it increased quality of HIV care (Sereda et al., Citation2020). The small number and heterogenous nature of the community and institutional level factors signals the importance of future research on these and other topics.

Discussion

To sum up, the quantitative intersectional stigma field is growing, spanning marginalisation based on race, HIV, sexual orientation, substance use, and gender. More recently, there has been inclusion of experiences of homelessness, sex work, and socioeconomic status. Future intersectional stigma research can expand to examine multiple and less studied experiences of marginalisation and structural oppression. Less than half (13/32, 40.6%) of the studies included in this review measured empowerment-based factors in addition to stigma. This is an area for growth in the intersectional stigma field, as identifying what factors can mitigitate stigma's impacts on wellbeing can inform future intervention development and policy. Findings suggest that the current field of quantitative intersectional stigma research could expand both the concepts that are studied to include more empowerment-based factors, as well as build methodological roadmaps for testing the protective roles of empowerment-based factors in contexts of intersectional stigma.

Most of the intersectional stigma studies that included empowerment-based factors examined interpersonal and intrapersonal level factors. Stigma was often reported to be associated with lower social support and/or resilience, and at times social support and resilience mitigated the effects of stigma on health outcomes. Future studies could more consistently test the mediating and moderating roles of social support and resilience to inform programming. ‘Main effects model’ approaches to social support point to its health benefits via social integration, self-esteem and self-worth (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985). Social support also has a buffering role for stress, whereby it can shift coping strategies and self-esteem, particularly if this support is high quality and salient to the lived experiences of the person (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985; Lakey & Cohen, Citation2000). Researchers can more fully explore the dimensions of social support including quality and quantity, sources of social support including from family, friends, and significant other(s), and its role in helping people navigate intersectional stigma. Similarly, a recent review of resilience among people living with HIV calls for multi-level approaches to resilience (Dulin et al., Citation2018). Multi-level resilience (individual, relational, collective) is underexplored in relation to intersectional stigma.

There are other factors that warrant further attention in intersectional stigma quantitative research. These include collective empowerment, resistance, solidarity, and community mobilisation and transformation. Learning from the rich body of qualitative intersectional stigma research could inform the application and adaptation of varying measures and would also point to the need to develop tools where there are none available. For instance, building community solidarity and activism networks could have ripple effects for funding advocacy, community-level stigma reduction strategies, as well as health benefits. It is plausible that there is a need for a blueprint for intersectional stigma quantitative research with measures for multi-level empowerment-based factors congruent with intersectionality's liberatory potential. To illustrate, Earnshaw et al. (Citation2016) examined HIV activism among persons living with HIV. Their study revealed that higher enacted HIV-related stigma was associated with increased HIV activism, and that HIV activists also reported higher social network integration, social wellbeing, life meaning, and active coping with discrimination. Yet they also caution that HIV activists had higher depressive symptoms than non-activists, calling for future nuanced explorations of stigma, activism and wellbeing (Earnshaw et al., Citation2016). Structural racism and other forms of intersecting structural stigma require urgent focus.

An increasing number of quantitative studies are assessing multiple forms of stigma and their intersection, with debates over whether there are more appropriate analytic methods than others (for instance, Bauer, Citation2014; Harnois et al., Citation2019; Logie et al., Citation2019; Turan et al., Citation2019). The purpose of this paper is not to serve a gatekeeping role or argue for one particular analytic approach. Turan et al. (Citation2019) provide multiple possibilities for measurement and analyses of intersectional stigma. Indeed, our review of how intersectionality is being applied in quantitative stigma research in shows the multitude of possibilities for integrating an intersectional approach into stigma research.

Based on our findings, we provide some recommendations for considering multi-level empowerment perspectives to enhance the liberatory potential of applying an intersectionality approach to stigma research. Researchers can theoretically situate their study in a comprehensive intersectionality framework. They may wish to revisit the Combahee River Collective Statement (Citation1977) to consider the ways that their study can address multiple, interlocking systems of oppression, as well as assess empowerment related to intersecting identities. They can identify what systems of oppression they will be measuring, and if they will be assessing social categories (e.g. ethnoracial identity) and/or systemic oppression (e.g. racism). Researchers can consider integration of multi-level empowerment perspectives into studies and explore how study findings could advance larger social justice and equity initiatives. Documenting community and structural strengths can be leveraged in practice, programming and policy.

A few limitations should be mentioned. We included studies that addressed stigma based on multiple identities/ stigma types and mentioned being informed by intersectionality. Perhaps this broad inclusion criteria captured studies that were too different to compare. It may also be that intersectionality was peripheral to the study. These exclusion criteria, while helpful in producing a manageable sample of intersectional stigma quantitative studies to review, may have inadvertently moved the analysis from intersectionality's critical race feminist roots. Future studies could use a wider inclusion criteria to encapsulate such studies. There was a MeSH term for social stigma but not intersectionality, which made it more challenging to identify relevant studies. The exclusion of non-peer reviewed reports may have missed a broader knowledge base on empowerment-based approaches to intersectionality from the community. Finally, we focused on the budding quantitative intersectional field in order to produce more precise analyses, but there is a much larger body of qualitative intersectional stigma research that was beyond the scope of this paper that could inform future quantitative research.

Implications

The study of the integration of empowerment-based perspectives in intersectional stigma studies has practical implications. This work can inform policy recommendations to address stigma and promote health equity. Without attending to strengths and the ways that communities are navigating inequalities, interventions may not realise their potential in ‘unleashing the power of resistance on the part of stigmatized populations and communities’ (Parker & Aggleton, Citation2003, p. 21). Yet, empowered communities acting in solidarity have the power to change policies that derive from and reproduce intersectional stigma. Moreover, empowerment-based perspectives encourage policies that truly shift power to stigmatised groups. Historically, efforts to address stigma have centred on prohibiting discrimination. For example, civil rights legislation passed in the U.S. in the 1960s banned discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex, and national origin in employment, housing, public accommodations, and federally funded programmes. The Black Lives Matter and other activist communities also teach the importance of moving beyond these ‘do no harm’ policies that risk maintaining the status quo to those that sustainably transform power structures within society (Black Lives Matter, Citationn.d.). In essence, an empowerment-based perspective calls for a fundamental re-envisioning of how stigma is addressed via policy. Policies should not only protect stigmatised groups from devaluation and disempowerment, but invest in valuing and empowering them.

Findings can inform the way that researchers design studies, and the very questions that are asked. Most quantitative stigma studies guided by intersectionality are not employing a radical perspective of intersectionality that addresses multi-level empowerment and the potential of individuals and communities to create a more equitable and just society. There is the possibility that by focusing only on marginalisation, researchers could inadvertently perpetuate stigmatising and hopeless perspectives regarding marginalised communities that they are studying. Tuck (Citation2009) described that the repercussions of damage-centred research include communities ‘thinking of ourselves as broken’ (p. 409). Alternatively, studies could produce valuable knowledge of marginalisation, while simultaneously signalling the ways in which people are navigating, coping, and resisting intersecting forms of stigma. This knowledge can be leveraged to attain funding to support and grow community level activism, wisdom and strength. Such an approach aligns with Tuck’s (Citation2009) invitation to research desire, a concept that encapsulates complexity, nuance, and self-determination. Community mobilisation, solidarity, resources and knowledge can be integrated into the development of health and social justice-related programmes and services.

We call for the examination of stigma based on marginalised identities, practices and health statuses, alongside the exploration of the myriad ways that people and communities are working to support themselves and one another and transform society. Measuring activism, stigma resistance, solidarity, social support, and multi-level resilience – among other empowerment indicators – has the potential to transform our knowledge base as researchers and in turn produce evidence to support policies and programmes to fuel social change and social justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, S. (2010). Forward: Secrets and silence in feminist research. In R. Ryan-Flood & R. Gill (Eds.), Secrecy and silence in the research process: Feminist reflections (pp. xvi–xxi). Routledge.

- Algarin, A. B., Zhou, Z., Cook, C. L., Cook, R. L., & Ibañez, G. E. (2019). Age, sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation: Intersectionality of marginalized-group identities and enacted HIV-related stigma among people living with HIV in Florida. AIDS and Behavior, 23(11), 2992–3001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02629-y

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(19), e32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Baral, S., Logie, C. H., Grosso, A., Wirtz, A. L., & Beyrer, C. (2013). Modified social ecological model: A tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 482. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-482

- Bastos, J. L., Harnois, C. E., & Paradies, Y. C. (2018). Health care barriers, racism, and intersectionality in Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.010

- Bauer, G. R. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022

- Black Lives Matter. (n.d.). #BlackLivesMatter: About. Downloaded January 21, 2021 from https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/

- Bouris, A., & Hill, B. J. (2017). Exploring the mother-adolescent relationship as a promotive resource for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 618–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12234

- Brown, R. L. (2014). Psychological distress and the intersection of gender and physical disability: Considering gender and disability-related risk factors. Sex Roles, 71(3), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0385-5

- Calabrese, S. K., Earnshaw, V. A., Magnus, M., Hansen, N. B., Krakower, D. S., Underhill, K., Underhill, K., Mayer, K. H., Kershaw, T. S., Betancourt, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2018). Sexual stereotypes ascribed to black men who have sex with men: An intersectional analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0911-3

- Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018854

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Combahee River Collective. (1995). Combahee River Collective statement. In B. Guy-Sheftall (Ed.), Words of fire: An anthology of African American feminist thought (pp. 232–240). New Press. Original work published 1977.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700108086364

- Dulin, A. J., Dale, S. K., Earnshaw, V. A., Fava, J. L., Mugavero, M. J., Napravnik, S., Napravnik, S., Hogan, J. W., Carey, M. P., & Howe, C. J. (2018). Resilience and HIV: A review of the definition and study of resilience. AIDS Care, 30(Suppl. 5), S6–S17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1515470

- DuPont-Reyes, M. J., Villatoro, A. P., Phelan, J. C., Painter, K., & Link, B. G. (2020). Adolescent views of mental illness stigma: An intersectional lens. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(2), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000425

- Dyar, C. E., Feinstein, B., Stephens, J., Zimmerman, A. R., Newcomb, M., & Whitton, S. W. (2020). Nonmonosexual stress and dimensions of health: Within-group variation by sexual, gender, and racial/ethnic identities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000348

- Earnshaw, V. A., Bogart, L. M., Dovidio, J. F., & Williams, D. R. (2013). Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: Moving toward resilience. American Psychologist, 68(4), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032705

- Earnshaw, V. A., Reed, N. M., Watson, R. J., Maksut, J. L., Allen, A. M., & Eaton, L. A. (2021). Intersectional internalized stigma among Black gay and bisexual men: A longitudinal analysis spanning HIV/sexually transmitted infection diagnosis. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(3), 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318820101

- Earnshaw, V. A., Rosenthal, L., & Lang, S. (2016). Stigma, activism, and well-being among people living with HIV. AIDS Care, 28(6), 717–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1124978

- Earnshaw, V. A., Smith, L. R., Cunningham, C. O., & Copenhaver, M. M. (2015). Intersectionality of internalized HIV stigma and internalized substance use stigma: Implications for depressive symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(8), 1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313507964

- English, D., Rendina, H. J., & Parsons, J. T. (2018). The effects of intersecting stigma: A longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 669–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000218

- Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster Inc.

- Goodin, B. R., Owens, M. A., White, D. M., Strath, L. J., Gonzalez, C., Rainey, R. L., Okunbor, J. I., Heath, S. L., Turan, J. M., & Merlin, J. S. (2018). Intersectional health-related stigma in persons living with HIV and chronic pain: Implications for depressive symptoms. AIDS Care, 30(Suppl. 2), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1468012

- Gutiérrez, L. M., Delois, K. A., & Glenmaye, L. (1995). Understanding empowerment practice: Building on practitioner-based knowledge. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 76(9), 534–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/104438949507600903

- Haile, R., Rowell-Cunsolo, T. L., Parker, E. A., Padilla, M. B., & Hansen, N. B. (2014). An empirical test of racial/ethnic differences in perceived racism and affiliation with the gay community: Implications for HIV risk. Journal of Social Issues, 70(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12063

- Harnois, C. E., Bastos, J. L., Campbell, M. E., & Keith, V. M. (2019). Measuring perceived mistreatment across diverse social groups: An evaluation of the everyday discrimination scale. Social Science & Medicine, 232, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.011

- Himmelstein, M. S., Puhl, R. M., & Quinn, D. M. (2017). Intersectionality: An understudied framework for addressing weight stigma. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.003

- Holley, L., Tavassoli, K., & Stromwall, L. (2016). Mental illness discrimination in mental health treatment programs: Intersections of race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-9990-9

- Ion, A., Wagner, A. C., Greene, S., Loutfy, M. R., & HIV Mothering Study Team. (2017). HIV-related stigma in pregnancy and early postpartum of mothers living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Care, 29(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1211608

- Jackson, S. D., Mohr, J. J., Sarno, E. L., Kindahl, A. M., & Jones, I. L. (2020). Intersectional experiences, stigma-related stress, and psychological health among Black LGBQ individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(5), 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000489

- Kippax, S., Stephenson, N., Parker, R. G., & Aggleton, P. (2013). Between individual agency and structure in HIV prevention: Understanding the middle ground of social practice. American Journal of Public Health, 103(8), 1367–1375. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301301

- Lakey, B., & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support theory and measurement. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 29–52). Oxford University Press.

- Levey, T. G., & Pinsky, D. (2015). ‘A world turned upside down’: Emotional labour and the professional dominatrix. Sexualities, 18(4), 438–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460714550904

- Lipperman-Kreda, S., Antin, T. M. J., & Hunt, G. P. (2019). The role of multiple social identities in discrimination and perceived smoking-related stigma among sexual and gender minority current or former smokers. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 26(6), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2018.1490391

- Logie, C. (2012). The case for the World Health Organization’s commission on the social determinants of health to address sexual orientation. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1243–1246. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300599

- Logie, C. H., & Daniel, C. (2016). ‘My body is mine’: Qualitatively exploring agency among internally displaced women participants in a small-group intervention in Leogane, Haiti. Global Public Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 11(2), 122–134. doi:10.1080/17441692.2015.1027249

- Logie, C., James, L., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. (2013). Associations between HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and depression among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2012.0296

- Logie, C. H., James, L., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. R. (2011). HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and Sex work: A qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in ontario, Canada. PLoS Medicine, 8(11), e1001124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124

- Logie, C. H., Jenkinson, J. I. R., Earnshaw, V., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. R. (2016). A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, housing insecurity and wellbeing among African and Caribbean black women living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE, 11(9), e0162826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162826

- Logie, C. H., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Kenny, K. S., Levermore, K., Jones, N., Baral, S. D., Wang, Y., Marshall, A., & Newman, P. A. (2018a). Social-ecological factors associated with selling sex among men who have sex with men in Jamaica: Results from a cross-sectional tablet-based survey. Global Health Action, 11(1), 1424614. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1424614

- Logie, C. H., Wang, Y., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Wagner, A. C., Kaida, A., Conway, T., Webster, K., de Pokomandy, A., & Loutfy, M. R. (2018b). HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Preventive Medicine, 107, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.018

- Logie, C. H., Williams, C. C., Wang, Y., Marcus, N., Kazemi, M., Cioppa, L., Kaida, A., Webster, K., Beaver, K., de Pokomandy, A., & Loutfy, M. (2019). Adapting stigma mechanism frameworks to explore complex pathways between intersectional stigma and HIV-related health outcomes among women living with HIV in Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 232, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.044

- Lyons, C. E., Olawore, O., Turpin, G., Coly, K., Ketende, S., Liestman, B., Ba, I., Drame, F. M., Ndour, C., Turpin, N., Ndiaye, S. M., Mboup, S., Toure-Kane, C., Leye-Diouf, N., Castor, D., Diouf, D., & Baral, S. D. (2020). Intersectional stigmas and HIV-related outcomes among a cohort of key populations enrolled in stigma mitigation interventions in Senegal. AIDS, 34(1), S63–S71. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002641

- Makowski, A. C., Kim, T. J., Luck-Sikorski, C., & von dem Knesebeck, O. (2019). Social deprivation, gender and obesity: Multiple stigma? Results of a population survey from Germany. BMJ Open, 9(4), e023389. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023389

- Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286

- Moore, K. E., Stein, M. D., Kurth, M. E., Stevens, L., Hailemariam, M., Schonbrun, Y. C., & Johnson, J. E. (2020). Risk factors for self-stigma among incarcerated women with alcohol use disorder. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000182

- Orza, L., Bewley, S., Logie, C. H., Crone, E. T., Moroz, S., Strachan, S., Vazquez, M., & Welbourn, A. (2015). How does living with HIV impact on women’s mental health? Voices from a global survey. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(6Suppl. 5). https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.6.20289

- Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304-0

- Rice, W., Logie, C., Napoles, T., Walcott, M., Batchelder, A., Kempf, M., Wingood, G. M., Konkle-Parker, D. J., Turan, B., Wilson, T. E., Johnson, M. O., Weiser, S. D., & Turan, J. (2018). Perceptions of intersectional stigma among diverse women living with HIV in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.001

- Rosengren, A. L., Menza, T. W., LeGrand, S., Muessig, K. E., Bauermeister, J. A., & Hightow-Weidman, L. B. (2019). Stigma and mobile app use among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 31(6), 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2019.31.6.523

- Sereda, Y., Kiriazova, T., Makarenko, O., Carroll, J. J., Rybak, N., Chybisov, A., Bendiks, S., Idrisov, B., Dutta, A., Gillani, F. S., Samet, J. H., Flanigan, T., & Lunze, K. (2020). Stigma and quality of co-located care for HIV-positive people in addiction treatment in Ukraine: A cross-sectional study. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25492

- Shangani, S., Gamarel, K. E., Ogunbajo, A., Cai, J., & Operario, D. (2020). Intersectional minority stress disparities among sexual minority adults in the USA: The role of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(4), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1604994

- Stangl, A. L., Earnshaw, V. A., Logie, C. H., Van Brakel, W., Simbayi, L. C., & Barré, I., et al. (2019). The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med, 17(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3

- Stewart, C., Oga, E., Kraemer, J., Mbote, D., Stockton, M., & Nyblade, L. (2019). Measuring anticipated sex-work stigma: Scale validation and association with HIV and non-HIV service utilization. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25327

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

- Turan, J., Elafros, M., Logie, C., Banik, S., Turan, B., Crockett, K., Pescosolido, B., & Murray, S. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

- Varas-Díaz, N., Rivera-Segarra, E., Neilands, T. B., Pedrogo, Y., Carminelli-Corretjer, P., Tollinchi, N., Torres, E., Valle, Y. S. D., Díaz, M. R., & Ortiz, N. (2019). HIV/AIDS and intersectional stigmas: Examining stigma related behaviours among medical students during service delivery. Global Public Health, 14(11), 1598–1611. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1633378

- Weisz, C., & Quinn, D. M. (2018). Stigmatized identities, psychological distress, and physical health: Intersections of homelessness and race. Stigma and Health, 3(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000093

- Yang, X., Li, X., Qiao, S., Li, L., Parker, C., Shen, Z., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Intersectional stigma and psychosocial well-being among MSM living with HIV in Guangxi, China. AIDS Care, 32(Suppl. 2), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1739205