ABSTRACT

Buyer’s clubs were first recognised during the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and focussed on knowledge curation and distribution of treatments. In the past decade, there has been a resurgence of buyer’s clubs, mostly focussed on hepatitis C treatment and PrEP. This paper aims to increase understanding of buyer’s clubs and stimulate discussion on their role in achieving equitable access to medicines. Our proposed definition of a buyer’s club is ‘a community-led organisation or group which seeks to improve an individual’s access to medication through knowledge sharing and/or distribution as its primary goal’. The logistical and relational infrastructures of buyer’s clubs have been mapped out. Networks and communities are integral to buyer’s clubs by facilitating practical aspects of buyer’s clubs and creating a sense of community that serves as a foundation of trust. For a user to receive necessary medical support, doctors play a crucial role, yet, obtaining this support is difficult. Whilst buyer’s clubs are estimated to have enabled thousands of people to access medicines, and they run the risk of perpetuating health inequities and injustices. They may have the potential to serve as a health activism tool to stimulate sustainable changes; however, this needs to be explored further.

Introduction

Despite formal recognition of the importance of access to medicines in achieving the human right to health (United Nations, Citation1966), there are nearly two billion people worldwide who lack access to essential medicines (World Health Organization, Citation2017). One key obstacle in achieving access is the pricing of medicines. Many medicines are being priced at levels unaffordable for payers, yet these increasing prices do not necessarily reflect an increased benefit (Morgan et al., Citation2020). A report commissioned by The Council for Public Health and Society in The Netherlands (Council for Public Health and Society, Citation2017) aimed to provide a comprehensive explanation as to why the current drug development process is resulting in excessively high-priced medicines and made suggestions as to how this can be tackled, (the report made six recommendations, these included; making using of legal instruments to strengthen negotiation, innovative negotiation strategies, giving research institutions more negation power over patents, creating a national Technology Transfer Office, utilising e-health and personal health dossiers to support medicine development and alternative models of research and development). One suggestion was to allow patients to purchase their medicines online through personal importation schemes. This suggestion, alongside the utilisation of the buyer’s clubs model, was also raised as a method of increasing access to direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) as a treatment for hepatitis C, a treatment which was even unaffordable for high-income countries (Douglass et al., Citation2018; Vernaz-Hegi et al., Citation2018). Subsequently, DAAs have become more affordable and accessible in high-income countries at least. However, given the increasing prices of medicines, it is feasible to expect a similar situation to occur in the not-so-distant future.

A short history of buyer’s clubs

Buyer’s clubs were first initiated during the HIV/AIDS pandemic of the 1980s. These groups referred to themselves as ‘the AIDS underground’ and were mostly concerned with disseminating information and analysis on existing treatment regimens alongside distributing treatments (Lune, Citation2007). It is the work of these health activists which became famous with the Hollywood movie ‘Dallas Buyer’s Clubs’, which told the story of Ron Woodroof, an American man who established his own buyer’s club in 1988 (IMDb, Citation2013). They again were brought to public consciousness with the establishment of several hepatitis C buyer’s clubs in response to the limited access to DAAs, attracting much media attention (Keep & Atkin, Citation2015; Woolveridge, Citation2015). Many other buyer’s clubs have been established, such as those focussed on the distribution of PrEP (Pre-exposure prophylaxis) to prevent HIV transmission and Orkambi, a cystic fibrosis treatment.

It is these cases of high-priced medicines being unaffordable for health services and therefore inaccessible for their patients, which exemplify the dilemma for health services as outlined by Daniels (Citation1979). For distributive justice or equity to be realised, then societies will need to regulate their share of resources in order to meet the healthcare needs of all (Daniels, Citation1979, Citation2001). High-priced medicines are then the locus of difficulties in the intersection between the right to health and distributive justice when a health system must deny people from realising their right to health due to issues of affordability. Could buyer’s clubs then be a method of rebalancing distributive justice when access to medicine is denied by a health system, or would Douglass et al. (Citation2018) be correct in their assertation that buyer’s clubs only offer short-term solutions and a more coordinated public health response is needed (Douglass et al., Citation2018)? From these perspectives, we should then question the role of buyer’s clubs in the wider access to medicines debate. Are they a sustainable method of rebalancing inequitable healthcare systems or do they only offer short-term benefits by offering immediate access to those able to utilise a buyer’s club?

Before acting upon recommendations of utilising the buyers’ clubs model, an increased understanding is required. Currently, minimal literature offering in-depth descriptions of buyer’s clubs exists – it is this literature gap which this paper aims to directly contribute to. HIV/AIDS buyer’s clubs have been referenced in discussions of how HIV/AIDS communities in New York City organised themselves in response to the pandemic (Lune, Citation2007). Vernaz-Heig et al. (Citation2018) suggested certain practical requirements which patients would need to meet to utilise a buyers’ club;

the patient is aware of his/her infection and that the patient is aware of a buyers’ club. It depends on the patient’s initiative to contact a buyers’ club, upload a medical prescription, pay with a credit card, provide the address where the drug will be delivered, sign a consent form, pay a minimum amount of CHF 1000, and be able to read English. (Vernaz-Hegi et al., Citation2018)

Consequently, the aim of this paper is two-fold; firstly, to increase understanding of buyer’s clubs by mapping their infrastructure, and secondly, to discuss their role in the access to medicines debate.

Methodology

Study design

To understand the infrastructure of buyer’s clubs, a qualitative design was chosen. This design allows the exploration of the phenomenon that is buyer’s clubs and takes the perspectives of participants into account.

Study setting and sampling methods

The data collection was conducted between June and July 2019. Due to the international nature of buyer’s clubs, no singular geographical location was selected as the research setting. A mixture of purposive and snowball sampling techniques was applied when identifying and recruiting participants to interview, participants were requested for an interview provided they met the inclusion criteria of having established or utilised a buyer’s club. Founders were contacted through direct e-mail via available contact details of buyer’s clubs found online. Several Facebook groups that served as platforms for buyer’s clubs were recommended by these founders as a method of recruiting users. User recruitment was achieved by making posts in these groups. Further participants were then recruited after being referred to by existing participants. A total of 15 participants were interviewed, seven buyer’s club founders, seven buyer’s club users, and one academic who broadly worked with buyer’s clubs and supported their mission. A founder was defined as an individual who had individually or as part of an organisation established a buyer’s club. A user was defined as an individual who had utilised a buyer’s club to purchase medication. The participants were based in one of the following countries: The United Kingdom, Singapore, the USA, Belgium, Bulgaria, and Australia. The buyer’s clubs involved in this research focussed on three different medication types, PrEP for HIV prevention, DAAs for hepatitis C treatment, and Orkambi for cystic fibrosis treatment. These categories were not purposefully selected, rather they are the categories that emerged from the data and are therefore not necessarily universal but reflect the characteristics of the study’s participants. A draft version of the research manuscript was shared with participants before submission, no major concerns or objections were raised.

Data collection

A scoping review of academic and grey literature was conducted, including scholarly papers and books, news articles, media interviews, social media (Facebook) pages, and websites of buyer’s clubs. Next, in-depth semi-structured interviews were held with 15 participants to confirm and deepen our current understanding of buyer’s clubs building upon the scoping review. All interviews bar one, which was conducted in person in The Netherlands, were conducted through an online communication platform. The interviews explored practical details of buyer’s clubs and how they functioned or were utilised, alongside an exploration of the experiences of participants. Considerations around sustainability and equity of buyer’s clubs were also explored during interviews.

Data analysis

The scoping review provided an overview of buyer’s clubs and their practicalities which provided a good grounding of understanding prior to the interviews and analysis. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and served as a basis for the thematic content analysis using a general inductive coding approach in order to summarise and convey the raw data into key themes as described by Thomas (Citation2006). This approach identified an initial 29 themes, the coding was then refined to remove overlaps and synthesise similar codes. This led to the resulting three themes; the logistical infrastructure, the relational infrastructure, and the impact of buyer’s clubs with more detailed sub-themes, which allowed a deeper understanding of buyer’s clubs in terms of how they work and what impact they have. They were then utilised to build a theoretical framework with the findings regarding impact contained in a separate section within the results.

Ethical considerations

Prior to data collection, ethical clearance was obtained with the identification number FHML/GH_2019.049. Upon agreement yet before the interview, participants were asked to read and sign an informed consent form. All interviews were taped and transcribed anonymously to ensure the confidentiality of all participants.

Results

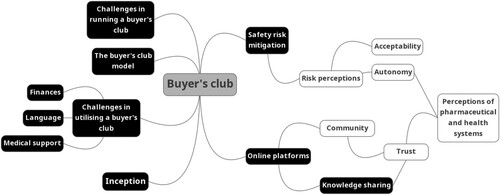

The initial scoping review provided insights mostly into the practicalities of buyer’s clubs, then the interviews served to confirm these observations and provided insights more phenomenological in nature not provided through the scoping review. This has been reflected in the employment of a dual-layered framework to map buyer’s clubs, the first pertaining to the more logistical aspects of buyer’s clubs, and the second pertaining to the more relational and less tangible aspects which involve the relationships between stuff, space, people, and system (Street, Citation2014). These two layers and their intersections have been mapped visually in , which represents the complexity of buyer’s clubs and the important nuances to be considered in discussions beyond the act of purchasing medicine online.

Figure 1. Visual representation of the logistical (black background) and relational (white background) infrastructure of buyer’s clubs.

The logistical infrastructure of buyer’s clubs

There is a spectrum of models and levels of the organisation across buyer’s clubs. Despite these differences, they were founded under similar circumstances and motivations to advocate for greater access to a particular medicine, with the formation of a buyer’s club being an unexpected consequence. Buyer’s clubs and users do not exist in a vacuum and rely upon knowledge sharing between one another. The internet and various online platforms are key in facilitating buyer’s clubs today, the type of platform and its utility depends on a buyer’s club’s way of working. Despite the casual format of some buyer’s clubs, all founders took the safety of users seriously. Whilst personal importation is legal, there are several logistical obstacles a buyer’s club must overcome, including credit facilities and customs control. Whilst a user might feel the impact of these obstacles in the service received, they face different obstacles to founder’s, including language and financial capabilities and obtaining support from a medical professional to provide a prescription and medical monitoring.

The buyer’s club model

It appeared that many individuals who set up buyer’s clubs did not identify themselves as following the ‘traditional model’ of direct importation of medicines, particularly those who focussed on PrEP. For example, one founder described their work solely as ‘helping with facilitating the individual legal purchases of PrEP … we’re not taking money from anyone’ (Founder 4). In contrast to other founders who described their work as being ‘more of a classic buyer’s club model’ (Founder 7), whereby upon receiving payment from a user, the order would be passed onto a supplier who dispatches the medication either directly to the user or to the buyer’s club who then sends it on to the user. Some are run using a more casual format, such as a Facebook group, where an individual can make a post or send a direct message to the group administrator who will send them the medicine via their supplier. Some have a more polished and professional approach with websites not dissimilar to an online shopping platform with a more traditional business structure.

Inception

Whilst buyer’s clubs took on different models, and they were often founded under similar circumstances. None of the founders had begun with the intention of establishing a buyer’s club. Rather, it was often the case that they were advocating for access to the medicine at a national level before learning of importation from overseas or were seeking the medicine for themselves and decided to disseminate this information. ‘My original intention was to provide a road map for other people wanting to get their treatment from India’ (Founder 7).

Knowledge sharing

Buyer’s clubs themselves formed networks which facilitated learning and knowledge, with the more experienced buyer’s clubs offering advice to the less experienced, ‘we took the legal and professional advice we’ve gathered … and sent it over to them’ (Founder 4). This same knowledge sharing was seen across users who would share their experience and knowledge with others either through local or social media channels or their social circles. Some were requested by their doctors to share their information with other patients, ‘he [my doctor] calls me every once in a while, and says listen, I have a gentleman that came in to see me, he has hepatitis C and I told them about your story. Do you mind coming in to do the consult with me?’ (User 4).

Online platform

All buyer’s clubs included in the research were run online through a variety of different platforms, these include websites, blogs, online merchant sites, and Facebook pages or groups. The type of platform utilised was interdependent on the formality a buyer’s club assumed and the early motivation of the founder. For example, one founder initially set up a blog to share their personal story of purchasing DAAs abroad, and this then expanded to include a Facebook group that facilitated the informal one-on-one contact with users to purchase DAAs via the buyer’s club. Whereas a founder whose primary aim had been to advocate for wider access to PrEP using their organisation’s formalised platform was able to then add information for users on how to purchase the medication. It is often through these online platforms that a user first discovers a buyer’s club, ‘I went onto Facebook and I searched hepatitis’ (User 4). These Facebook groups are extremely active, with members asking for advice after just being diagnosed or whilst taking their treatment, alongside sharing media stories related to their situations. Perhaps the most surprising type of post made in these groups is when members post a picture of their recent test results asking for help in deciphering its meaning.

Safety risk mitigation

Founders of buyer’s clubs took safety risks seriously with many conducting extensive therapeutic drug monitoring or bioequivalence testing on the imported medications. In some cases, founders even took the time to understand the personal circumstances of a user ‘I always check which other medications they’re on … I don’t take any chances with people health’ (Founder 3). The results of some of these studies have been published in scientific journals (Hill et al., Citation2018).

Challenges of running a buyer’s club

Despite the shipment of a small package of medicines for personal use being legal under international law, issues often arise over payments. Many major banks do not allow their services to be used for the selling of medicines, ‘they will cut off your credit card facilities instantly … we were cut off 2 days ago’ (Founder 2). It is not always feasible for a buyer’s club to provide the level of customer service a user might expect when they make a purchase, with buyer’s clubs described as being ‘not wonderfully easy to use … it can take 2 or 3 weeks to get a response to an email’ (User 6). Another challenge is the importation of medicines to certain countries with some custom regulations being stricter than others, which can require complex arrangements. ‘I send the medicine to people in Austria or UK and then he would travel to Austria and pick up the medication and then take it back to Serbia’ (Founder 7).

Challenges of utilising a buyer’s club

All buyer’s clubs included in the study were run by native speakers resulting in information being made available in English only. One non-native speaker described the downsides of this, ‘it’s very complicated if you don’t speak English so you will never have access to it’ (User 7).

Despite the relatively lower price of generic medicines available via a buyer’s club, affordability remains a challenge for users, ‘if I had the money, I would have done it sooner’ (User 1). Highlighting that acquiring medications through buyer’s clubs is still not a possibility for many, particularly if from a lower-income country as described by a Bulgaria-based user, ‘I would say that 95% of the people who are interested in the medication cannot afford it’ (User 7).

The challenge of ensuring that the medication could be available to all those who needed it was a recurring theme for founders, with it being acknowledged that they were ‘a really iniquitous solution’ (Founder 5). Consequently, founders described their attempts to address accessibility by providing the medication at no or reduced cost to certain groups, such as those on a low income. The financial resource to do this was generated through attaching an extra, often optional fee or through charitable partnerships.

Whilst buyer’s clubs allow a patient to effectively bypass their national healthcare system, a certain level of support from the health system is required in terms of prescribing and monitoring. This can vary across medication types as users with hepatitis C, for example, require viral load monitoring. All participants who utilised a hepatitis C buyer’s club spoke of some difficulty in finding a doctor, ‘my original physician who diagnosed me with hepatitis C in 2008 was not willing to risk his licence by providing me with a prescription’ (User 4). Ultimately all participants were successful, but in some cases, this took months to achieve, and one user had to sign a liability waiver. Users often utilised medical connections or were able to persuade doctors using their research on buyer’s clubs. Several participants believed that this difficulty in gaining support was due to doctors’ concerns of risking support from pharmaceutical companies or being held liable for medical malpractice.

The relational infrastructure of buyer’s clubs

The type of risk perception of buyer’s clubs varies between founders and users, but ultimately these risks are deemed worth taking. Participant’s perceptions of pharmaceutical and health systems were largely negative, with a strong sense of autonomy over healthcare decisions evident in participants. However, participant’s decisions to run or utilise a buyer’s club often faced challenges from others, yet this did not undermine the strong sense of trust user’s put in buyer’s clubs. Additionally, buyer’s clubs themselves provided a sense of community where one can connect and share with others in similar circumstances.

Risk perceptions

Upon first consideration of establishing or utilising a buyer’s club, users and founders alike were required to process their perceptions of risk. A key concern for users was that the medicine would be fake, and they would be at a financial loss. From the founder’s perspective, there were other legal concerns, ‘how much trouble can we get into for advocating this? Who’s going to come after us?’ (Founder 6). Nevertheless, the risk perception of buyer’s clubs was outweighed by the posed benefits, ‘I’m not averse to go to prison … I think it’s a greater need’ (Founder 3).

Perceptions of pharmaceutical and health systems

A strong sense of anger towards the pharmaceutical industry was often expressed by participants, ‘we’re dealing with monsters; we’re dealing with like vile corporate greed that’s beyond even pharma greed, it's honestly a whole new level’ (Founder 6). This anger had often grown in tandem with their experience of not accessing the medicine they required as they began to believe the industry was prioritising profit over health.

Many participants expressed negative perceptions of their national healthcare service, often pinpointed to specific instances where individuals felt their concerns were ignored by their doctor. As such, there was a shared sentiment that healthcare professionals were allied with the pharmaceutical industry, an alliance prioritised above patients ‘they’re going to push whatever the pharma rep has just been in their office with and paid them off for’ (User 3).

Autonomy

For all participants, there was evidence of strong self-advocacy when it came to health decision-making, ‘I want to have autonomy over my own healthcare’ (User 5). It was this wish for greater autonomy that drove users to look for alternative ways to access the medicine they need. It is this same autonomy and desire to make informed choices over their lives that provides the foundation for individuals to question the intentions of pharmaceutical and health systems.

Acceptability

Many funders and users alike spoke of challenges posed by others who did not easily accept the work of buyer’s clubs, which questions the acceptability of buyer’s clubs on a societal level. These challenges included others being upset at the accessibility of buyer’s clubs or being afraid a buyer’s club would undermine access by impeding the progress of pricing negotiations between their national government and a pharmaceutical company, ‘some patients in the community have got this massive fear that if you push [the pharmaceutical company] too hard, they will walk away’ (Founder 6). As such, others felt that efforts would be better focussed solely upon advocating for the medication to be accessible on a wider level, rather than on establishing or supporting buyer’s clubs.

Trust

All participants referenced the importance of trust in their experience with buyer’s clubs. As described prior, many buyer’s clubs ran tests on the medication to help build trust, but users often required further proof, ‘the kind of elements of trust I needed was social proof’ (User 5). Seeing a buyer’s club featured in mainstream media was often very persuasive for users as it legitimised the concept of buyer’s clubs, ‘he’d been on TV, so I saw him as genuine’ (User 2). The period it took for sufficient levels of trust to be developed varied across users, spanning weeks to months.

Another prominent aspect was the lack of trust individuals expressed in their governments and health systems and the shared sentiment that they had been let down. Consequently, they placed their trust instead in buyer's clubs who they felt prioritised their health, ‘I trusted him because someone's being honest and kind and true and not ripping you off’ (User 3).

Community

A sense of community was apparent in many users’ stories, and often individuals expressed the feelings of support they were able to gain from this community, alongside it being a source of knowledge and advice. Even when medicine became more accessible, as with DAAs, this community continued, ‘it is now not so much a buyer’s club, rather a support group’ (Founder 7). However, this sense of comradery and support was not expressed by a participant in the cystic fibrosis community who described the buyer’s club as worsening an already divided community.

The impact of buyer’s clubs

It appears that buyer’s clubs have a dual-pronged aim; firstly, to achieve more immediate access to medicines on an individual level and secondly, to disrupt the bigger system to have a more sustainable and wide-reaching impact whereby medicines are made accessible through their national health service. However, a user’s experience of utilising buyer’s clubs impacts other areas of their life, particularly their perceptions of and trust in health systems. Many founders utilise their knowledge and experience and apply it to buyer’s clubs for different conditions or in other parts of the world. This diversification is seemingly needs-driven; thus, founders of buyer’s clubs expressed a belief that their model was a sustainable one, which will only become more prevalent.

It was difficult to obtain specific numbers or a demographic breakdown of people who had utilised a buyer’s club, as this information was not often collated by founders. However, some estimated tens of thousands of people had accessed a medicine through a buyer’s club. As highlighted by one founder, many more people went to directly purchase medicines for themselves, informed or inspired by a buyer’s club but not directly utilising the buyer’s club service. Additionally, some founders spoke of assisting individuals in setting up their own local or national buyer’s clubs.

Discussion and conclusion

Mapping of buyer’s clubs

A key aim of this study was to improve the understanding of buyer’s clubs through mapping their infrastructure.

One key finding was the differences in the models that buyer’s clubs follow. One participant suggested that only those who serve as financial middlemen and are directly involved in the ordering and shipment of medications meet the definition of buyer’s clubs. However, this would then be contradictory to the original HIV/AIDS buyer’s clubs in the 1980s and other groups who conduct knowledge curation and dissemination on available treatment options and how they can be obtained. Therefore, a proposed definition of buyer’s clubs is as follows; a community-led organisation or group which seeks to improve an individual’s access to medication through knowledge sharing and/or distribution as its primary goal. The definition consequently offers a distinction to online pharmacies or other online importation schemes as it notes that the main purpose of a buyer’s club is to facilitate access through more grass-roots initiatives versus being driven by the commercial opportunity to produce profits.

As in all aspects of our globalising world, the addition of the internet and social media into the fora of buyer’s clubs has stimulated an evolution in the working of buyer’s clubs compared to their 80s counterparts. Users often reported being part of online communities through which they found companionship and support from others in similar situations. The prominence of community and trust in buyer’s clubs is unsurprising when considered through a social theory lens. Carpiano (Citation2006) proposed a framework for understanding neighbourhoods and social processes as health determinants. Carpiano’s model outlines how an individual’s social capital- conceptualised as social support, social leverage, informal social control, and neighbourhood organisation participation; and social cohesion – conceptualised as connectedness and values, are influenced by neighbourhood factors, which in turn influences an individual’s attachment to their neighbourhood, health behaviour and health status. The community of buyer’s clubs could arguably be described as a form of neighbourhoods that seemingly provide the foundations of connectedness and trust between users and founders. It is from this foundation of social cohesion which social capital can arise, such as the support from which individuals can draw upon from buyer’s clubs which then influences their health behaviour and status.

The demand for a buyer’s club is created when a healthcare system cannot provide a necessary medicine. However, regular health services are still required to provide a prescription and medical monitoring. The experiences of users in accessing this care highlight the differences in doctors’ perceptions of buyer’s clubs as it appears that some doctors are more sympathetic to the cause than others. Additionally, users often described negative experiences with their healthcare system, which led to feelings of mistrust. It is this mistrust that creates space for buyer’s clubs, as users instead put their trust in the buyer’s club who they perceived as caring about their health and welfare more than their health system.

All participants, whether users or founders, appeared to retain a strong sense of autonomy and therefore were predisposed to searching for alternative methods of accessing their medicine. This exhibition of self-advocacy noted in participants is unsurprising as this is often something expressed by those with chronic conditions (Brashers, Haas, & Neidig, Citation1999). Interesting parallels can be drawn between buyer’s clubs and AIDs activist organisations, as individuals in buyer’s clubs also appear to match the traits seen in those with HIV/AIDS who join activist movements and have a self-advocacy orientation. These traits include having a problem-focussed coping strategy, greater knowledge of relevant information sources, and social network integration (Brashers, Haas, Neidig, & Rintamaki, Citation2002). However, the cause and effect of this trait development are unclear. Is it that individuals with these traits are more attracted to partake in activism or buyer’s clubs, or is it the experience itself that propagates these traits in an individual? Further investigation is required before any firm conclusions can be made concerning individual characteristics.

(In)equitability of buyer’s clubs

In their essence, buyer’s clubs challenge the concept of distributive justice in healthcare systems. They refute the notion that an individuals’ fair share of health resources has been pre-determined based on the affordability and thus the accessibility of medicines – which is an output of the price-setting by pharmaceutical companies and the subsequent decision by a state to purchase and make a medicine available through its health system. Instead, they have put in place or utilised a system that allows the individual to bypass this pre-determined resource distribution and still access the medicine, and one could argue they are an example of distributive subjectivism (Arneson, Citation1990).

Whilst the individual situation and health of the person using a buyer’s club improves, they do little to improve the situation of those who cannot utilise a buyer’s club in the short-term. To utilise a buyer’s club, an individual must have financial capability. Income is a well-known social determinant of health; those who belong to this relatively elite group and can utilise buyer’s clubs are inherently more likely to have better health outcomes than their more deprived counterparts (Adler et al., Citation1994). Furthermore, to find a doctor who would offer their support, participants often utilised their existing networks with members of the medical field or were able to persuade the doctor upon showcasing their research into buyer’s clubs. This again highlights the relevance of social capital in the buyer’s club sphere, to obtain medical support, they draw upon resources provided to them by their networks (Carpiano, Citation2006). Again, these are tools not available for all to utilise. Therefore, a major concern is that the benefits of buyer’s clubs can only be felt by those belonging to this elite group and thereby perpetuate existing health inequities.

However, the unjust nature of buyer’s clubs is something that prays heavily on the minds of founders, hence why many offer some discount or coupon schemes to increase accessibility. Another way in which buyer’s clubs could argue that they are indeed just is their activism efforts and aims of disrupting the system to stimulate more systemic changes at a policy level. As described previously, buyer’s clubs often began as groups of individuals working together to run advocacy campaigns before evolving into buyer’s clubs; as such, health activism is at their core.

If buyer’s clubs aim to disrupt the system and create sustainable changes, they could still serve to rebalance distributive justice in health systems by creating equitable access to medicines. For this, buyer’s clubs could function as an advocacy tool, as was ultimately the case for the Orkambi CF buyer’s club based in the UK which received significant media attention (Boseley, Citation2019; Cohen, Citation2019) and successfully created sufficient public and political pressure which resulted in the medication becoming available under the UK national health service (NHS England, Citation2019). In this instance, the buyer’s club, whilst initially only accessible for those with sufficient financial resources, led to the medication being available for all those who needed it in the UK.

Limitations and recommendations

A key limitation of this study was the lack of interviews conducted with doctors, particularly as the findings of this study indicated the important role they have in the function of buyer’s clubs. Unfortunately, attempts at contact with doctors for this study were unsuccessful, and reasoning undisclosed. This might reflect the feared repercussions from supporting a buyer’s club as reported by users. Therefore, it is necessary for this group of actors to also be interviewed in future studies to understand their attitudes towards buyer’s clubs.

A methodological limitation of this study was the inclusion criteria for ‘users’. It was required that an individual has purchased a medicine through a buyer’s club to meet the definition of ‘user’. However, this study found that there are different spectrums along which a buyer’s club sat with some focussed on knowledge distribution as opposed to direct purchasing. As such, an individual who utilised a buyer’s club to obtain information on treatment options and how to obtain treatment could be defined as a ‘user’ but were not included in the sample. Similarly, due to the study design, only those who are part of these buyer’s club communities were interviewed. Therefore, little is known as to how these communities are perceived on the outside by those affected by the same access issues. Several participants reported the polarisation buyer’s clubs caused within patient communities. This indicates that the acceptability of buyer’s clubs may differ across patient communities and should be investigated further.

A further limitation is the very different cultural and regulatory contexts of participants. This is likely a result of the purposive sampling technique and the small number of buyer’s clubs in existence which creates a small sampling group. Despite the differences of participants, users and founders alike are brought together in this new transnational digital space of working, which enables them to find a regulatory and cultural setting that best fits their common needs.

There was potential selection bias of the researcher due to them being a native English speaker and therefore not having access to non-English platforms; as such only participants able to speak English could be recruited. It was noted that a key characteristic of participants was their strong initiative and risk-taking; however, this could be exaggerated due to participant personality bias of online recruitment. This may have resulted in participation bias as individuals recruited through online recruitment techniques are more likely to have a personality type that is more open to new experiences (Buchanan, Citation2018). More research is required into the individual traits of users and founders of buyer’s clubs.

The future of buyer’s clubs

Receiving medical support is a crucial aspect for a user of buyer’s clubs, but currently, there appears to be resistance coming from some doctors. Whilst this study is unable to provide definite reasons for this it was suggested by participants that doctors are unclear of the legalities and safety risks regarding buyer’s clubs. Therefore, if support for buyer’s clubs is integrated at the policy level, then it will provide doctors with space to openly support patients.

Presently, it appears that buyer’s clubs are only easily accessible for a somewhat elite group, those with a strong command of English and sufficient disposable income. Consequently, despite their intentions, buyer’s clubs are not able to achieve increased access for all in an equitable manner to ensure distributive justice. There are several routes buyer’s clubs can take to try and become more equitable. One way is to increase their charitable initiatives, whereby those without the financial capacity can still utilise a buyer’s club through coupon or discount schemes, as already seen in most buyer’s clubs. To stimulate greater systemic change, they would need to pool together their efforts and expertise to gain more comprehensive support across a range of stakeholders in the political and medical world. However, in The Netherlands, a letter from the Minister for Medical Care on online importation of medicines stated ‘the fact that Dutch patients can order prescription medicines online without the intervention of a doctor and pharmacist is worrying and undesirable’ (Minister voor Medische Zorg, Citation2019). This demonstrates that the earlier recommendation for buyer’s clubs in a report commissioned by the Dutch government (Council for Public Health and Society, Citation2017) has not been considered as a legitimate option. This raises concerns over how political support can be achieved on a wider scale if a country, such as The Netherlands, often considered progressive in its stance on access to medicines, does not openly support online importation, even following the recommendations of a report its government commissioned.

Conclusion

This paper builds upon a small pool of existing literature on buyer’s clubs and represents the first empirical study of buyer’s clubs using a qualitative approach. It does not aim to serve as an exhaustive analysis of buyer’s clubs; rather, its primary purpose is to improve understanding of the infrastructure of buyer’s clubs, thereby facilitating future analysis. Prior literature had focussed on what we have referred to as the logistical aspects of buyer’s clubs, whereas this paper has been able to contribute an understanding of the relational aspects and thus demonstrating a previously unrecognised complexity of buyer’s clubs. As this paper demonstrates, buyer’s clubs are a complex phenomenon containing an array of important themes, each deserving further exploration beyond the scope of this paper. Yet, arguably one of the most important questions regarding buyer’s clubs which this paper aimed to stimulate initial discussion on, is how successful they can be at achieving increased access to medicines. It appears that equity and sustainability are key challenges of buyer’s clubs and need to be reflected upon carefully. Yet, whilst they may or may not have the capability to increase access in an equitable manner, this paper does highlight the lived experience of an individual and the lengths they will go to when they are denied access to medicines.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all participants who took part in this research and shared their experiences with buyer’s clubs. The authors also thank Wilbert Bannenberg of Stichting Farma ter Verantwoording (Dutch Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation) for his early support and guidance during this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adler, N. E., Boyce, T., Chesney, M. A., Cohen, S., Folkman, S., Kahn, R. L., & Syme, S. L. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist, 49(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.49.1.15

- Arneson, R. J. (1990). Liberalism, distributive subjectivism, and equal opportunity for welfare. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 158–194.

- Boseley, S. (2019). Families create buyers club for cut-price cystic fibrosis drug. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jun/04/families-create-buyers-club-for-cut-price-cystic-fibrosis-drug

- Brashers, D. E., Haas, S. M., & Neidig, J. L. (1999). The patient self-advocacy scale: Measuring patient involvement in health care decision-making interactions. Health Communication, 11(2), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1102_1

- Brashers, D. E., Haas, S. M., Neidig, J. L., & Rintamaki, L. S. (2002). Social activism, self-advocacy, and coping with HIV illness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(1), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502191006

- Buchanan, T. (2018). Personality biases in different types of ‘internet samples’ can influence research outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.002

- Carpiano, R. M. (2006). Toward a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: Can bourdieu and sociology help? Social Science & Medicine, 62(1), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.020

- Cohen, D. (2019). Inside the UK's drug buyers’ clubs. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-48357762

- Council for Public Health and Society. (2017). Development of new medicines. https://www.raadrvs.nl/documenten/publications/2017/11/09/development-of-new-medicines—better-faster-cheaper

- Daniels, N. (1979). Rights to health care and distributive justice: Programmatic worries. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 4(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/4.2.174

- Daniels, N. (2001). Justice, health, and healthcare. American Journal of Bioethics, 1(2), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1162/152651601300168834

- Douglass, C. H., Pedrana, A., Lazarus, J. V., ‘t Hoen, E. F. M., Hammad, R., Leite, R. B., Hill, A., & Hellard, M. (2018). Pathways to ensure universal and affordable access to hepatitis C treatment. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1162-z

- Hill, A., Tahat, L., Mohammed, M. K., Tayyem R. F, Khwairakpam, G., Nath, S., Freeman, J., Benbitour, I., & Helmy, S. (2018). Bioequivalent pharmacokinetics for generic and originator hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals. Journal of Virus Eradication, 4(2), 128–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30257-0

- IMDb. (2013). Dallas Buyers Club. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0790636/?ref_=tt_ch

- Keep, J., & Atkin, M. (2015). Hepatitis C sufferer imports life-saving drugs from India, takes on global pharmaceutical company. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-20/hepatitis-c-sufferer-imports-life-saving-drugs-from-india/6712990

- Lune, H. (2007). Urban action networks: HIV/AIDS and community organizing in New York City. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Minister voor Medische Zorg. (2019). Kamerstuk 29477, nr. 565. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-29477-565.html.

- Morgan, S. G., Bathula, H. S., & Moon, S. (2020). Pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems. BMJ, 368, l4627.

- NHS England. (2019). NHS England concludes wide-ranging deal for cystic fibrosis drugs [Press release]. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2019/10/nhs-england-concludes-wide-ranging-deal-for-cystic-fibrosis-drugs/

- Street, A. (2014). Rethinking infrastructures for global health: A view from West Africa and Papua New Guinea. http://somatosphere.net/2014/12/rethinking-infrastructures.html

- Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx

- Vernaz-Hegi, N., Calmy, A., Hurst, S., Jackson, Y. L. J., Negro, F., Perrier, A., & Wolff, H. (2018). A buyers’ club to improve access to hepatitis C treatment for vulnerable populations. Swiss Medical Weekly, 148, w14649.

- Woolveridge, R. (2015). Real life Dallas Buyers Club operation helps hepatitis C patients with free drugs. The Sydney Morning Herlads. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/real-life-dallas-buyers-club-operation-helps-hepatitis-c-patients-with-free-drugs-20151129-glamtm.html

- World Health Organization. (2017). Access to medicines: making market forces serve the poor. https://www.who.int/publications/10-year-review/chapter-medicines.pdf?ua=1