ABSTRACT

We examine the typologies of workplaces for sex workers in Dnipro, Ukraine as part of the larger Dynamics Study, which explores the influence of conflict on sex work. We conducted a cross-sectional survey with 560 women from September 2017 to October 2018. The results of our study demonstrate a diverse sex work environment with heterogeneity across workplace typologies in terms of remuneration, workload, and safety. Women working in higher prestige typologies earned a higher hourly wage, however client volume also varied which resulted in comparable monthly earnings from sex work across almost all workplace types. While sex workers in Dnipro earn a higher monthly wage than the city mean, they also report experiencing high rates of violence and a lack of personal safety at work. Sex workers in all workplaces, with the exception of those working in art clubs, experienced physical and sexual violence perpetrated by law enforcement officers and sex partners. By understanding more about sex work workplaces, programmes may be better tailored to meet the needs of sex workers and respond to changing work environments due to ongoing conflict and COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Workplaces for sex workers are meeting places where sex workers connect with clients, either in physical spaces such as hotels, brothels, massage parlours, highways, truck-stops, or strip clubs – or virtual spaces where sex workers may connect with clients and/or engage in online sex work. These workplaces have distinct physical, social, political and economic conditions which create different contexts for practicing sex work (Aral et al., Citation2003; Argento et al., Citation2019). The different workplace conditions in turn give rise to differences in risks, such as sexually transmitted and blood borne infections (STBBI) transmission and acquisition, violence, police maltreatment, violations of social and labour rights, and experiences of stigma and discrimination (Belmar et al., Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2015; Duff et al., Citation2015; Lewis et al., Citation2005; Szwarcwald et al., Citation2018).

Efforts have been made to define distinct typologies of workplaces for sex work. Some studies have examined associations between structural, social and economic features of workplaces and STBBI risk factors for sex workers (Argento et al., Citation2019; Goldenberg et al., Citation2011; Hong & Li, Citation2011; Yi et al., Citation2010) and others have explored and described workplace typologies (Aral et al., Citation2003, Citation2006; Aral & St Lawrence, Citation2002; Buzdugan et al., Citation2009, Citation2010; Lorway et al., Citation2017). One such study conducted in Santiago, Chile developed a comprehensive typology of workplaces for female sex workers using mapping and qualitative methods, arguing that the characterisation of different workplace types is an essential step to supporting future research on STBBI surveillance and prevention efforts (Belmar et al., Citation2018). Another study in Indonesia using mixed methods found that the typologies of sex work (categorised by urban/rural milieu, direct/indirect operation, and venue/non-venue-based) were more closely related to non-condom usage than the awareness or availability of condoms, highlighting the significance of considering context and work environments when designing HIV intervention programming (Puradiredja & Coast, Citation2012).

Two important factors that lead to workplaces contributing negatively to sex workers’ health and safety are the criminalisation of sex work in many settings, and the stigmatisation of people who practice sex work (Benoit et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Bruckert et al., Citation2003; Lazarus et al., Citation2012; Lowman, Citation2000; NSWP, Citation2017; Van der Meulen, Citation2010). For instance, criminalisation of sex work has been shown to limit access to sexual health information and STBBI prevention services (Anderson et al., Citation2016). Similarly, occupational stigma has been associated with barriers to access for services for sex workers (Lazarus et al., Citation2012) as well as violence, traumatic stress, and burnout (Alschech, Citation2019). Other studies have shown the protective effect that organised workplaces for sex work and third parties, such as managers or security, can have for sex workers. In workplaces with an organisational structure, established policies and protocols including security measures, client screening and offering information on STBBI prevention have been shown to increase occupational health and safety, and improve economic agency (Goldenberg et al., Citation2015, Citation2018; McBride et al., Citation2019).

In Ukraine there are an estimated 86,600 female sex workers working in a variety of sex work environments (UNAIDS, Citation2018). Selling sex services is considered an administrative offense (Article 181.1, Ukrainian Code on Administrative Offenses), while managing or organising sex work is a criminal offense however, the purchase of sex services is not criminal in any form (Articles 302 and 303, Ukrainian Criminal Code, Citation2001; Pyvovarova & Artiukh, Citation2020). Ukraine has higher HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) prevalences than the European average, and has the second largest HIV epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia after Russia (Maistat et al., Citation2017; UNAIDS, Citation2018). HIV transmission in Ukraine is largely attributed to unsafe injecting practices and condomless sex (Rhodes et al., Citation2002; Tokar et al., Citation2019), with the latter risk largely concentrated among female sex workers and their clients, and among men who have sex with men (Tokar et al., Citation2019; Vitek et al., Citation2014). The HIV prevalence among female sex workers in Ukraine is approximately five times that of the adult general population (UNAIDS, Citation2018). This paper exists within a larger project which aims to assess the influence of conflict on the dynamics of sex work and the HIV and HCV epidemics in Dnipro, Ukraine (Becker et al., Citation2019).

The conflict, located in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, arose in the spring of 2014 on the tails of the political upheaval of the Maiden Revolution, or Revolution of Dignity, and the annexation of Crimea. At the same time, Ukraine was facing a serious macroeconomic crisis which continued to devolve in response to the conflict and did not begin to show improvement until 2016, due in large part to the assistance of several multi-billion-dollar loans (Havlik et al., Citation2020). Ukraine has experienced a series of macro-level structural changes which modified its socio-political and economic context (Nizhnikau & Moshes, Citation2016; Novakova, Citation2017). Concern exists over whether the HIV epidemic will worsen in the wake of enduring conflict, given the associations with the consequences of conflict and HIV risk factors (Holt, Citation2018; Kazatchkine, Citation2017; Vasylyeva et al., Citation2018). Since the conflict’s onset, approximately 1.5 million people in Ukraine have been internally displaced (UNHCR, Citation2020); 13,000–13,200 people have died; and 29,000–31,000 others have been injured (OHCHR, Citation2020). Violence and population movement are well known HIV risk factors (Durevall & Lindskog, Citation2015; McGrath et al., Citation2015; Olawore et al., Citation2018; Pannetier et al., Citation2018) as well as common consequences of conflict (IOM UN Migration, Citation2019; Mock et al., Citation2004). Sex workers’ capacities to engage in STBBI prevention and sexual and reproductive health services can be severely limited during times of conflict (Ferguson et al., Citation2017). The shifting social, political, and economic pressures brought on by conflict may subject the social organisation of sex work, including the workplace, to change (Aral et al., Citation2003, Citation2006). Furthermore, presently layered atop the changes engendered by conflict are those suddenly brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic which has likely also incurred great change in the sex work industry (Platt et al., Citation2020).

Understanding workplace typologies for sex work is important to inform and support overall workplace health and safety for sex workers (Aral et al., Citation2003, Citation2006; Belmar et al., Citation2018; Buzdugan et al., Citation2009; Harcourt & Donovan, Citation2005). Different workplace typologies require different programmatic support, and it is important to understand where women work and how their workplaces differ in order to adapt programmes appropriately to their needs (Ikpeazu et al., Citation2014). Given sex work exists in the informal economy there is a gap in knowledge about the sex work industry in Ukraine. In this paper, we aim to fill this gap by exploring workplace typologies for sex work in Dnipro, Eastern Ukraine, by examining the organisation and patterns of workplaces and their impact on the safety and well-being of sex workers, during the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. We describe the main typologies of workplaces for sex work, the profile and earnings of women working at the different typologies, as well as their client volume, experiences of violence and perceptions of safety.

Methods

Study setting and population

The study took place in Dnipro, Dnipropetrovsk oblast, Ukraine, an industrial city of 1-million people located approximately 200 km from the conflict zone in the Donbas region of Ukraine. Dnipro has become a key destination for internally displaced persons, and a transit city for frontline forces (Becker et al., Citation2019; UNHCR, Citation2017). There are approximately 1087 (range 817–1357) sex workers in Dnipro (McClarty et al., Citation2018). Our study populations included cis-female sex workers aged 14 years and older who had engaged in sex work for at least 3 months. The age of majority in Ukraine is 18, the legal age for consent for marriage is 17 for women and the age of consent for sexual activity is 16. A previous study conducted in Ukraine identified female participants as young as 14 years of age who self-identified as sex workers (Becker et al., Citation2018). Participants in this study under the age of majority were treated as mature minors and therefore provided consent to participate themselves.

Study design and data collection

The project employed a cross-sectional design, which included mapping of workplaces, followed by a bio-behavioural survey among female sex workers. Data were collected from September 2017 to October 2018. Geographic mapping of workplaces provided information on sex work ‘hotspots’ (locations where sex workers solicit and/or provide services to clients) and estimated the population size of sex workers within hotspots and by workplace typology across the city (Cheuk et al., Citation2019; Emmanuel et al., Citation2013). Workplaces for sex work can also be virtual spaces such as websites where people engage in online sex work, however we have restricted our description to physical spaces. Sampling followed a two-stage sampling design: in the first stage, a representative sample of hotspots was randomly selected after stratifying the hotspots by administrative division and type of hotspot; in the second stage, sex workers at each hotspot were randomly sampled. The sample size for each selected hotspot was proportional to the size of the sex worker population estimated in the hotspot from the mapping (Becker et al., Citation2019).

A cross-sectional bio-behavioural survey was conducted among 560 female sex workers; 651 sex workers were approached, 91 declined to participate for a response rate of 86.0%. Participants were recruited from the selected hotspots by outreach workers who were members of the research team and connected to networks of female sex workers. Trained interviewers obtained written informed consent and administered a face-to-face structured questionnaire in Russian, the most common language for everyday communication in the region. The survey took approximately 45 min to complete and was conducted at the spot (either within the workplace or in a nearby project van). The survey consisted of questions around socio-demographic characteristics, numbers and types of sexual partners, HIV and HCV risk behaviours and experiences, programme/healthcare access, and questions specific to the influence of conflict on sex workers’ lives and livelihoods. Those who provided consent received HIV and HCV rapid testing conducted by a certified medical worker; pre- and post-test counselling were also provided (Becker et al., Citation2019). Participants were compensated with a 250 UAH ($9.20 USD) honorarium.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Manitoba Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba [HS20653(H2017:097)], Canada, the Ethical Review Committee of the Sociological Association of Ukraine, and the Committee on Medical Ethics of the L. Gromashevsky Institute of Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases at the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine.

Analysis

Data were analysed using Stata15 to present descriptive statistics and measures of central tendency outlining select workplace typologies.

Definitions

The definitions of workplace typologies for sex workers are presented in Box 1.

Workplace Typologies Definitions

‘Office’ Owned and operated by one or more managers who employ sex workers, and possibly other employees such as office administrators or security guards, and where owners take a portion of the revenue generated by sex work to cover their operating costs and make a profit

Apartment Generally include one or more women working out of an apartment which they might own or rent and where they may or may not also reside

Massage parlour/sauna A massage parlour where massage service can be purchased or sauna, both of which are not exclusively for sex work

Entertainment venue An adult entertainment venue such as a casino or dance club

Café/bar A café, bar or restaurant which is open to the public

Art club/strip club The venue may appear as more of a nightclub or strip club, with the understanding that additional sex services may be purchased there

Hotel/motel A hotel or motel

Public place An open-air space such as a public park or street

Highway/truck-stop Along a highway or at a truck stop which is along the highway, although services could be provided elsewhere such as in a car

Other A dormitory or boarding school

Variables of interest

Our variables of interest included those describing the organisation and practice of sex work, and experiences of violence and feeling of safety while doing sex work (grounded in our project’s conceptual framework, see Becker et al., Citation2019). Variables of interest included are: main workplace for meeting clients in the past 30 days, self-reported ‘prestige’ of primary workplace (derived from the question: ‘How would you rate the prestige of this place’ and referring to their main workplace), number of regular client (frequent and familiar clients with consistent and repeated encounters which become expected) and occasional client (unfamiliar or sporadic clients from which patronage is not expected) visits in a 30-day period, number of military clients in a 30-day period, hourly wage (derived from the question: ‘How much do you get paid for yourself per hour?’), proportion of monthly income from sex work, household income from sex work (obtained by multiplying proportion of household income derived from sex work by the total household income in the past 30 days), dependents supported with respondents total income, ever experienced physical or sexual assault by law enforcement, physical or sexual assault by a sex partner (clients and other intimate partners) in the past 3 months, and personal safety (derived from ‘On a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = completely unsafe and 5 = completely safe, how would you rate your personal safety as a sex worker?’). We also present data on other sex partners, these include transactional sex partners defined as partners with whom there is an expectation of receiving money, gifts or other resources in return for sex, but the price is not negotiated upfront rather implicitly understood; intimate partners, defined as those with whom there is no explicit expectation of receiving something for sex and an established (or anticipated) long-term relationship exists, such as husband, common-law partner or boyfriend; and casual sex partners defined as acquaintances with whom there is no expectation of receiving something in return for sex and no intention of establishing a long-term relationship.

Results

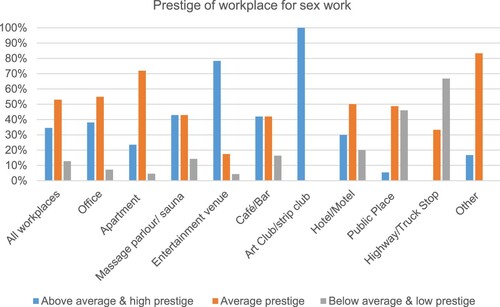

The median age of women we interviewed was 26 years old (interquartile range [IQR] = 22–30 years) (). Women self-reported an average socio-economic status (SES), a median of 4 (IQR = 3–5) on a 1–7 SES scale (7 being the highest), 93% of women had completed high school, and 53% reported having one or more dependents. Fifty-five per cent of the respondents were single and never married, 14.9% were living with a partner (married or otherwise), 6.3% were married not living with a partner, and 24.1% were widowed or divorced. Overall, participants reported engaging in sex work for a median of 5 years (IQR = 2–8). The majority of women named ‘offices’ (40.0%) or apartments (27.3%) as their main workplace. Fifty-nine per cent of respondents reported working in one workplace over the preceding 12 months. Art clubs/strip clubs were reported as having the highest prestige of the workplaces, and highways/truck-stops and public places were viewed as having the lowest prestige (). In the next sections, we describe offices, apartments, art clubs/strip clubs, public places and highway/truck-stops workplaces using descriptive statistics and measures of central tendency. We chose these workplaces as they represent the most common workplaces, as well as places ranked the most and least prestigious.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participantsa.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Socio-demographic characteristics are shown in . The youngest participants primarily worked at art clubs/strip clubs and the oldest worked on highways/truck stops. Participants working in art-clubs and offices self-identified the highest SES with a median of 5 (IQR = 4–6) and 5 (IQR = 4–5) respectively, while women working primarily on highway/truck stops had the lowest self-reported SES (median [IQR] = 2.5 [2–4]). Women who were art-club- and entertainment venue-based had been practicing sex work for the least number of years with a median of 2 (IQR = 1–8) and 2 (IQR = 1–9) years respectively. Hotel/motel followed by highway/truck stop-based had been practicing sex work the longest with a median of 8 (IQR = 5–15) and 6.5 (IQR = 4–9) years respectively.

‘Offices’

Offices were most commonly identified by sex workers as their main workplace (n = 224, 40.0%; ). Fifty-five per cent of women described offices as being of average prestige and 38.0% described them as above average or high prestige (). The majority (90.2%) of participants reported that managers solicit clients for them, 20.1% had ‘middle people’ such as a taxi drivers or hotel workers solicit for them, and 42.4% indicated that they solicited their own clients, there was overlap in these responses as many women used more than one method for soliciting clients. Women reported a median of 35.5 (IQR = 26–52) client visits in a 30-day period. In the same timeframe, participants reported a median of 20 (IQR = 15–30) occasional client visits and 12 (IQR = 6–24) regular client visits; of those clients, 1 (IQR = 0–2) was a military client. In the past 30 days, 42.1% of the women who primarily worked out of an office reported one or more transactional sex partners, 34.4% reported intimate sex partners, and 21.4% had one or more casual sex partners.

Table 2. Main workplace for sex worka.

Seven per cent of office-based sex workers reported ever having been physically assaulted by law enforcement while practicing sex work, while 4.5% reported ever experiencing sexual assault. Two per cent of office-based sex workers reported being physically or sexually assaulted by a sex partner (clients or intimate/casual partners) in the past 3 months. Office-based sex workers rated their personal safety as a sex worker as reasonably safe (median score [IQR] = 4 [3–5]) on a 1 (completely unsafe) to 5 (completely safe) scale.

Office-based sex workers earned a median of 700 UAH per hour ($25.80 USD). Total monthly income from sex work was 11,400 UAH ($419.50 USD), which represented 75% of their total monthly household income. This is much higher than the Dnipro city mean monthly wage which was 6912 UAH (254.40 USD) in 2017 (Ukrstat.org, Citation2019). Forty-three per cent of women supported one or more dependents with their income: 23.7% supported children, 12.1% supported partners, 17.4% supported parents/grandparents, and 5.8% others.

Apartments

The second most common workplace setting was an apartment (n = 153, 27.3%). Seventy-two per cent of women described apartments as being of average prestige and 23.5% described them as above average to high prestige. The majority of apartment-based workers reported that managers solicit clients for them (91.5%), 28.7% reported using a middle person, and 73.9% of women reported soliciting on their own. Women reported a median of 35 (IQR = 28–48) client visits in a 30-day period, with 27 (IQR = 20–38) occasional client visits and 10 (IQR = 5–20) regular client visits; of those clients 2 (IQR = 0–2) were military clients. In the past 30 days, 68% of apartment-based workers reported having had transactional partners, 74.5% reported intimate partners, and 41.8% had casual partners.

Twenty per cent of apartment-based sex workers reported ever having been physically assaulted and 7.8% reported ever being sexually assaulted by law enforcement while doing sex work. Three per cent of apartment-based sex workers reported being physically or sexually assaulted by a sex partner in the past 3 months. The median rating for personal safety by apartment-based sex workers was 3 (IQR = 2–4).

Apartment-based workers reported earning a median wage of 700 UAH per hour ($25.80 USD). The median total monthly income earned from sex work was slightly less than office-based workers: 10,000 UAH ($368.00 USD), which represented 70% of total monthly household income. Sixty-three per cent of women had one or more dependents: 41.8% supported children, 16.3% supported partners, 30.7% supported parents/grandparents, and 3.3% others.

Art clubs/strip clubs

While only 4.8% (n = 27) of women reported working in art clubs/strip clubs, the art club was described as being the most prestigious workplace. All women who named art clubs as their main workplace described them as above average or high prestige. Clients were solicited by managers (44.4%), a middle person (48.2%) and on their own (22.2%). Women working at an art club saw fewer clients. They reported a median of 23 (IQR = 15–33) client visits in a 30-day period; with 13 occasional (IQR = 9–17) client visits and 12 (IQR = 4–20) regular client visits; of those clients 0 (IQR = 0–2) were military clients. In the past 30 days, 22.2% had transactional partners, and 29.6% had intimate partners.

None of the art club-based sex workers reported ever having been physically or sexually assaulted by law enforcement while doing sex work; none of them reported being sexually or physically assaulted by a sex partner in the previous 3 months. The median rating for personal safety by art club-based sex workers was 4 (IQR 3–4).

Women working primarily at an art club earned 1600 UAH ($58.90 USD) per hour and reported a total median monthly income from sex work of 11,525 UAH ($424.20 USD), which represented 80% of their total monthly household income. Twenty-six per cent of women had one or more dependents: 18.5% supported parents/grandparents.

Public places

A small group of respondents worked mainly out of a public place (n = 37, 6.6%). Forty-nine per cent of women who worked in public place-based locations felt that it was of average prestige and 46.0% reported their workplace to be of lower prestige. Nearly all women (97.3%) reported independently soliciting clients, while some used a middle person (37.8%), and a small number of women (5.4%) reported having a manager. Women working in public places saw fewer clients than those working in offices and apartments. In the past 30 days, they had a median of 28 (IQR = 20–44) client visits, with 12 (IQR = 4–18) occasional client visits and 18 (IQR = 11–30) regular client visits, of those clients 1 (IQR = 0–2) were military. For women who worked in public spaces, 51.4% reported transactional partners, 35.1% reported intimate partners and 32.4% reported having sex with casual partners in the past 30 days.

Nineteen per cent of the women working in public places reported ever having been physically assaulted and 14% had been sexually assaulted by law enforcement while doing sex work. Twenty-two per cent of public place-based sex workers reported being physically or sexually assaulted by a sex partner in the past 3 months. The median rating for personal safety by public place-based sex workers was 3 (IQR = 2–3).

People working primarily out of public places earned 300 UAH ($11.00 USD) per hour and a total median monthly income from sex work of 6150 UAH ($226.30 USD), which constituted 80% of their total household income. Fifty-nine per cent of women supported one or more dependents with their income: 29.7% supported children and 43.2% supported parents/grandparents.

Highways and truck-stops

Thirty women (5.4%) cited working at highways and truck-stops. Highways were viewed by the women who worked there as having the lowest prestige of all the workplaces. Two-thirds of women working in highway-based settings reported their workplace to be of below average to low prestige and one-third reported it as average prestige. Most women did their own soliciting (93.3%), almost half were assisted by a middle person (43.3%), and a few worked with managers (13.3%). Sex workers at this workplace had a median of 39.5 (IQR = 27–49) client visits in a 30-day period; with 20 (IQR = 13–25) occasional client visits and 19 (IQR = 12–31) regular client visits, of those clients 4 (IQR = 3–6) were in the military. For women working primarily at a highway-based, 33.3% reported having sex with a transactional partner in the past 30 days, 30% reported having intimate partners, and 23.3% reported having sex with a casual sex partner.

Seventeen per cent of the highway-based sex workers reported ever having been physically assaulted and 6.7% had been sexually assaulted by law enforcement while doing sex work. Thirty per cent of highway-based sex workers reported being physically or sexually assaulted by a sex partner in the past 3 months. The median rating for personal safety by highway-based sex workers was 2 (IQR = 2–3).

Highway-based sex workers reported earning 400 UAH ($14.70 USD) per hour from sex work and a total median monthly income from sex work of 10,000 UAH ($368.00 USD), which represented 96% of their total monthly household income. Seventy-seven per cent of women supported one or more dependents with their income: 40.0% supported children, 23.3% supported partners, and 53.3% supported parents/grandparents.

Multiple workplaces

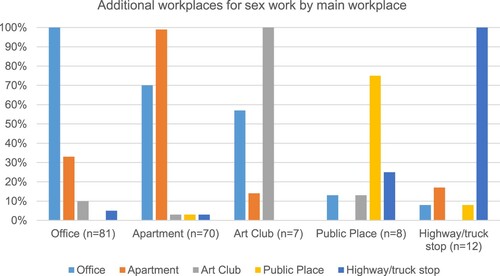

Two-fifths (n = 228, 40.2%) of the women interviewed reported working in more than one workplace, among them 132 (58.7%) worked in 3 or more places (). Women working at multiple places were slightly older (median [IQR] = 27 [23–31] years) than those working at one place (median [IQR] = 25 [22–29.5] years). Forty-eight per cent of women working in multiple places were single and never married versus 59.6% in single workplaces; 13.6% of women in multiple workplaces were living with a partner (versus 15.7% in single place); 7.9% were married not living with spouse (versus 5.1% in single place); and 30.7% widowed or divorced (versus 19.6% in single place).

Sex workers working at multiple workplaces had a higher number of client visits in a 30-day period, with a median of 40 client visits (IQR = 28–60 visits) versus those working at one place who saw a median of 31 client visits (IQR = 23–43 visits) (). Similarly, women working at multiple workplaces had more occasional client visits than those working in a single workplace, with a median of 24.5 client visits (IQR = 15–41 visits) and 18 client visits (IQR = 13–26 visits) respectively. Regular client visits were also higher, with a median of 16 client visits (IQR = 8–24 visits) versus 10 client visits (IQR = 6–20 visits). The number of military clients seen by sex workers working at multiple workplaces was 0 (IQR = 0–2) in the past 30 days and in a single workplace was 1 (IQR = 0–2). A higher proportion of women working in multiple workplaces had transactional partners (57% versus 43%); slightly more had intimate partners (49% versus 43%), and far more had casual sex partners (45% versus 20%).

Twenty per cent of women working at multiple workplaces versus 8% of those at single workplaces reported ever having been physically assaulted by law enforcement; 11% of women working at multiple workplaces versus 3% had been sexually assaulted by law enforcement while doing sex work. The median rating for personal safety by women working at multiple workplaces was 3 (IQR = 2–4) and for women at single workplaces was 4 (IQR = 3–4).

Total monthly income from sex work was almost the same between women working at multiple workplaces versus single workplaces. Women working at multiple workplaces made 10 500 UAH (IQR = 8000–12,800 UAH) per month ($386.40 USD [IQR = $294.40–471.00 USD]) compared to women working at one place who reported making 10 000 UAH (IQR = 8000–13,000) per month ($368.00 USD [IQR = $294.40–478.40 USD]); sex work made up 70% (IQR = 60–85%) of household income for people at multiple workplaces and 80% (IQR = 60–100%) for people at single workplaces. A higher proportion of women working in multiple workplaces had dependents (61% versus 48%): 36.4% supported children (versus 25.6% of women working at one workplace), 18.4% supported partners (versus 10.8%), 29.4% supported parents (versus 26.2%), and 7.0% supported others (versus 4.8%).

Table 3. Single workplace versus multiple workplaces.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate a diverse sex work environment in Dnipro, Ukraine, with heterogeneity across workplace typologies in terms of remuneration, workload, and safety. Experience of violence and feelings of safety varied across workplaces. Sex workers in all workplaces, with the exception of those working in art clubs, experienced physical and sexual violence perpetrated by law enforcement officers and sex partners. Highway and public place-based sex workers reported more violence compared with sex workers at offices and art clubs. In our study, women across workplaces, with the exception of those working in public places, reported earning more money than the Dnipro city mean monthly wage of 6912 UAH (254.40 US$) in 2017 (Ukrstat.org, Citation2019). Women working in higher prestige places earned a higher hourly wage, however client volume also varied which resulted in comparable monthly earnings from sex work across almost all workplace types. Highway-based sex workers had the most client visits in a 30-day period.

A cross-sectional survey of sex workers in 27 cities across Ukraine conducted in 2015–2016 paints a somewhat different picture of workplace typologies. The predominant workplaces were streets, roads or highways (35.7%), ‘via intermediaries’ (25.8%) and apartments/via internet (19.4%) (Sereda & Sazonova, Citation2016). A preceding study conducted in 2013 included a breakdown of workplaces for sex work in Dnipro. The proportion of sex workers who called street/highway/motorway their main workplace was much higher (11%) than this study and those who said flats/virtual were their main workplace to connect with clients was much lower (8%). Similarly, to sex workers who were office-based in this study, ‘via intermediaries’ was the largest group, although it was much larger than in our study (61%) (Balakirieva et al., Citation2014). The differences in workplace typologies in the various studies illustrate how sex work industries differ across the country; Dnipro’s sex work industry is largely based on managerial-style establishments, such as offices or via intermediaries. The studies also demonstrate how the landscape of workplaces for sex work can change over time. Compared with the previous surveillance study, the proportion of sex workers in Ukraine who work through intermediaries and in apartments has increased overtime (Sereda & Sazonova, Citation2016).

Exposure to violence has been associated with other STBBI risk behaviours (Choi et al., Citation2008; Decker et al., Citation2010; Deering et al., Citation2013; Wirtz et al., Citation2015), and higher client volume has been associated with STBBI prevalence, which can increase risk due to more exposure (Decker et al., Citation2012; Mishra et al., Citation2009). Offices were most frequently named by sex workers as their main workplace, a sex work venue which was ranked as one of the safest work environments by the women in this study. Offices and apartments appeared to share many characteristics; however, apartment-based sex workers reported far more violence from law enforcement officers. Many studies have documented that third parties have protective effects in criminalised sex work contexts for sex workers’ health, safety, rights, and agency to negotiate condoms as well as enabling economic agency, because organisational structures often have established policies and protocols around security measures, client screening, and STBBI prevention (Goldenberg et al., Citation2015, Citation2018; McBride et al., Citation2019). Yet, as described in a systematic review of sex work environments, HIV prevention and occupational safety remains largely dependent upon the legal context of sex work (Goldenberg et al., Citation2018).

The largest groups of women supporting children were apartment- and highway-based sex workers. With apartments and offices appearing to share many workplace characteristics with the exception that offices offer a safer working environment, it raises the question as to why women opt to work in these places? Studies in other contexts have found that some women prefer to work in independent work environments because of a desire for flexibility and autonomy, fear of managerial exploitation and economic independence, despite the physical and psychosocial vulnerability trade-off (Goldenberg et al., Citation2015). Additionally, women’s complex pragmatic decision-making in managing sex work and parenting has been explored in a qualitative study conducted in Mysore, India. Sex workers who became mothers shifted work hours to accommodate caring for their children while continuing to practice sex work so as to financially provide for their children, and save for their future financial needs, such as education (du Plessis et al., Citation2020). Despite their contextual differences, these studies share a commonality, that women doing sex work with financial and familial responsibilities continue to make decisions which best suit their needs within an environment of constraints. As Bruckert and Parent (Citation2013) have pointed out ‘sex workers, like any other workers, are selecting their labour location with the context of a constrained range of options’ (p. 62). Although there may be certain drawbacks to working in these workplaces – for instance both apartments and highways provide a less safe work environment – workplace flexibility and autonomy, especially for someone who has dependents to support, may be considered a worthwhile trade-off.

We observed that the majority of sex workers had few visits from military clients, with highway-based workers reporting seeing the highest number of these clients. Historically conflict, and therefore military presence, has created growth in demand for sex work (see for example, Brodeur et al., Citation2018; de Wildt, Citation2019). Our results do not illustrate a large increase of sex work demand in the city by military personnel at the time of the survey. It is possible that the presence of military ebb and flow and therefore was not captured, or that their position as military personnel remained hidden from the women in our study over time. Women working on highways had the highest number of military clients, conceivably seeing military clients as they travel to and from the conflict zone.

Our results corroborate work done in Côte d’Ivoire, which observed that violence against sex workers was associated with features of work environments. Police refusal to provide protection, as well as harassment or intimidation by police, were associated with physical and sexual violence against sex workers. The authors argued for the need for structural interventions and policy reforms to improve workplace health and safety (Lyons et al., Citation2017). In Ukraine, as in other contexts, much of the violence sex workers experience is committed by law enforcement officers (see for example, Demchenko et al., Citation2019; Lyons et al., Citation2017; Platt et al., Citation2018; Rhodes et al., Citation2008; Sereda & Sazonova, Citation2016; Sherman et al., Citation2015). A 2016 study found that almost half (46.6%) of female sex workers in cities across Ukraine had experienced violence while doing sex work. Comparable with our results, violence was more common among street-based sex workers. The majority of sex workers (82.1%) experienced violence from customers and more than 1 in 10 respondents (12.4%) reported cases of violence by law enforcement officers. Approximately half of those who had experienced violence during commercial sex had sought help (Sereda & Sazonova, Citation2016). Physical and sexual violence are important determinants of STBBI risk for women in sex work (Decker et al., Citation2010, Citation2012; Pando et al., Citation2013; Peitzmeier et al., Citation2020; Swain et al., Citation2011) and violence against sex workers is enabled by the criminalisation of sex work (Deering et al., Citation2014; Shannon & Csete, Citation2010). A qualitative study of sex work in Nigeria found that sex workers experienced multiple forms of violence (physical, emotional, sexual, and economic violence) perpetrated by partners, clients, other sex workers, and law enforcement which the author linked to the criminalisation and stigmatisation of sex work (Nelson, Citation2020). Sex workers globally argue for the decriminalisation of sex work and acceptance of sex work as work, pointing to the evidence that criminalisation and other forms of legal oppression negatively impact the safety and health of sex workers, including their risks of contracting STBBIs (Benoit et al., Citation2019; Bruckert et al., Citation2003; Demchenko et al., Citation2019; Lazarus et al., Citation2012; Lowman, Citation2000; Lyons et al., Citation2020; NSWP, Citation2017; Platt et al., Citation2018; Shannon et al., Citation2015; Van der Meulen, Citation2010). In one meta-analysis, the authors concluded that repressive policing of sex workers was associated with increased risk of violence from clients or other parties, STBBI infection, and condomless sex (Platt et al., Citation2018).

The decriminalisation of sex work is urgently needed to increase the safety of sex work, especially as the women in our study experienced high rates of violence at the hand of law enforcement officers. By highlighting the differences between sex work workplaces and the versatility offered by different work environments, the decriminalisation of sex work would likely improve workplace safety such as it has in New Zealand (Abel et al., Citation2009; Abel & Fitzgerald, Citation2012). A draft law was submitted to the Ukrainian government in 2015 to consider the legalisation of sex work–which included the provision of social guarantees and labour protectionisms for sex workers however it was withdrawn due to ‘massive outcry’ from the public (Pyvovarova & Artiukh, Citation2020). It is important to note the distinction between the legalisation and the decriminalisation of sex work: decriminalisation is used to describe ‘opposition to all forms of criminalisation and other legal oppression of sex work and sex workers’ (NSWP, Citation2014, p. 2), while the legalisation of sex work generally means that although it is not illegal to practice sex work various aspects of sex work might be limited or controlled by state regulation and enforced by police (NSWP, Citation2014). Sex workers in Ukraine have reported that if sex work were decriminalised, they would expect the following: safer working conditions and lower risk of violence; legal protection from the police; decreased levels of societal stigmatisation and self-stigmatisation; reduction of health risks, including STBBI infection; the ability to determine the conditions for communicating with clients and the ability to access healthcare without fear (Demchenko et al., Citation2019; Pyvovarova & Artiukh, Citation2020).

In this study a large number of sex workers reported working in multiple locations; further analysis of these networks might help in understanding the interconnections of spaces and their overlapping risks, thus informing where and when to implement relevant preventative programming. Women working in multiple workplaces frequently worked in a space of the same typology, or one with a comparable prestige level and possibly similar earning expectations. Heterogeneous sex work typologies have been observed in other studies conducted around the world which concluded that work environment features blended with context shaped sex worker experiences with negotiating HIV and STBBI prevention (Argento et al., Citation2019; Goldenberg et al., Citation2015; Puradiredja & Coast, Citation2012). The varying features across workplace typologies for sex workers may speak to the different needs and experiences of women in choosing these spaces as their main workspace. By enhancing our understanding of workplaces for sex work, programmes may be better tailored to meet the needs of sex workers.

Limitations

This study is cross-sectional, and the results of this paper are descriptive in nature. We therefore cannot infer causality between workplace typologies and our variables of interest. The study also relies on self-reported data. Sensitive variables, such as violence, may be subjected to underreporting through social desirability bias. Experiences of violence may have been underreported as is often the case with accounting for violent experiences (Femi-Ajao et al., Citation2020; Fisher et al., Citation2003). Other variables of note which were self-reported and may be subject to recall, social desirability, and misclassification biases were experiences of assault, prestige of workplace, SES, solicitation method, and client visits.

In this study we cannot infer how much time is spent doing sex work. We have measured workload by client visits in the past 30-days, however women likely do far more work related to sex work than their time spent with clients: advertising, communicating, scheduling, waiting on no-show clients, et cetera. It is also likely that time spent with clients varied considerably, which was not captured in our survey. Further qualitative research into the features of the work environment would shed light on the more nuanced differences of workplace features.

There are limitations with how we measured income from sex work. The way sex workers set prices can be elastic. Depending on the workplace environment, sex workers may have some control over price setting and adjust according to transaction conditions. We reported average earnings per hour because the majority of women (87.9%) reported being paid per hour, but sex workers may charge a flat fee per client visit or per type of service, or use a combination of these methods. It is important to note that earnings from sex work can fluctuate depending on the individuals’ circumstances and on the season. In Ukraine, sex work can be seasonal, especially for those who work outdoors. Self-reported income is accompanied with a broad range of possibilities for bias and measurement error: incentives to underreport, difficulties for respondents or people to estimate their income due to lack of knowledge, misunderstanding, recall problems, confusion and sensitivity to the topic (Moore et al., Citation2000). Studies have shown that self-reported income for self-employed people is often under-reported (Cabral & Gemmell, Citation2018; Hurst et al., Citation2014; Pissarides & Weber, Citation1989).

Conclusion

In this paper, we explore the sex work industry in Dnipro, Eastern Ukraine, by examining the typologies of workplaces for sex work and the safety of sex workers, to understand the industry context during the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. While sex workers in Dnipro earn a higher monthly wage than the city mean, they also report experiencing high rates of violence and a lack of personal safety in their workplaces. The decriminalisation of sex work in Ukraine and globally has the potential to minimise the risks and harms experienced by sex workers, regardless of which space women practice sex work. By understanding more about workplaces, programmes may be better tailored to meet the needs of sex workers as the context within which they work shifts and respond to changing work environments due to ongoing conflict and COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgements

This work is conducted in partnership with the Ukrainian Institute for Social Research after Oleksandr Yaremenko (UISR), the Alliance for Public Health in Ukraine, the Dnipro Oblast AIDS Centre and the Center for Public Health, the Ministry of Health in Ukraine. We thank all of the Dynamics Study Participants for sharing their time and experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ukrainian Code on Administrative Offenses. Article 181.1 “prostitution”. (The Code is supplemented by Article 181-1 in accordance with the Decree of the JHA № 4134-11 of 12.06.87, as amended in accordance with the Law № 55/97-ВР of 07.02.97.) Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/cgi-bin/laws/main.cgi?nreg=80731-10#Text

- Criminal Code of Ukraine. (2001, April 5). № 2341-III (as amended and supplemented on 23.11.2018 г.). Article 302 “Establishment or maintenance of premises and procuration” and article 303 “Sex trafficking or enticement into prostitution”. http://continent-online.com/Document/? doc_id=30418109#pos=1;-77

- NSWP. (2014). Sex work and the law: Understanding legal frameworks and the struggle for sex work law reforms. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://www.nswp.org

- NSWP. (2017). Policy brief: Sex work as work. Retrieved June 17, 2019, from https://www.nswp.org

- UNHCR. (2017). Evaluation of UNHCR’s Ukraine country programme. Retrieved November 8, 2019, from https://www.unhcr.org/5a182d607.pdf

- UNAIDS. (2018). Global AIDS monitoring 2018: Ukraine summary. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/UKR_2018_countryreport.pdf

- IOM UN Migration. (2019). World migration report 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020, from https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/wmr_2020.pdf

- Ukrstat.org: State Statistics Service of Ukraine documents publishing. (2019). Time series of average monthly wages by region (1995–2018). Retrieved January 23, 2020, from https://ukrstat.org/en/operativ/operativ2006/gdn/prc_rik/prc_rik_e/dszpR_e.htm

- OHCHR. (2020). Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 November 2019 to 15 February 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://www.ohchr.org/en/countries/enacaregion/pages/uareports.aspx

- UNHCR. (2020). Ukraine: Internally displaced persons (IDP). Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://www.unhcr.org/ua/en/internally-displaced-persons

- Abel, G., & Fitzgerald, L. (2012). ‘The street’s got its advantages’: Movement between sectors of the sex industry in a decriminalised environment. Health, Risk & Society, 14(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2011.640664

- Abel, G., Fitzgerald, L., & Brunton, C. (2009). The impact of decriminalisation on the number of sex workers in New Zealand. Journal of Social Policy, 38(3), 515. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279409003080

- Alschech, J. (2019). Predictors of violence, traumatic stress, and burnout in sex work [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Toronto. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/97315

- Anderson, S., Shannon, K., Li, J., Lee, Y., Chettiar, J., Goldenberg, S., & Krüsi, A. (2016). Condoms and sexual health education as evidence: Impact of criminalization of in-call venues and managers on migrant sex workers access to HIV/STI prevention in a Canadian setting. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-016-0104-0

- Aral, S., & St Lawrence, J. (2002). The ecology of sex work and drug use in Saratov Oblast, Russia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 29(12), 798–805. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-200212000-00011.

- Aral, S., St Lawrence, J., Tikhonova, L., Safarova, E., Parker, K., Shakarishvili, A., & Ryan, C. (2003). The social organization of commercial sex work in Moscow, Russia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 30(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-200301000-00009

- Aral, S., St Lawrence, J., & Uusküla, A. (2006). Sex work in Tallinn, Estonia: The sociospatial penetration of sex work into society. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(5), 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2006.020677.

- Argento, E., Goldenberg, S., & Shannon, K. (2019). Preventing sexually transmitted and blood borne infections (STBBIs) among sex workers: A critical review of the evidence on determinants and interventions in high-income countries. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3694-z

- Balakirieva, O., Bondar, T., Loktieva, I., Sazonova, Y., Sereda, Y., & Hudik, M. (2014). Summary of the analytical report “Monitoring the behaviour and HIV-infection prevalence among female sex workers as a component of HIV second generation surveillance”. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://aph.org.ua/

- Becker, M., Balakireva, O., Pavlova, D., Isac, S., Cheuk, E., Roberts, E., Forget, E., Ma, H., Lazarus, L., Sandstrom, P., Blanchard, J., Mishra, S., Lorway, R., & Pickels, M., on behalf of the Dynamics Study Team. (2019). Assessing the influence of conflict on the dynamics of sex work and the HIV and HCV epidemics in Ukraine: Protocol for an observational, ethnographic, and mathematical modeling study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 19(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-019-0201-y

- Becker, M., Balakirieva, O., Isac, S., Cheuk, E., Pavlova, D., McClarty, L., Mishra, S., Pickles, M., Lorway, R., Sandstrom, P., Blanchard, J., & Nugent, Z. (2018). Estimating early HIV risk among at risk adolescent girls and young women in Dnipro, Ukraine. 2018 соціологія ISSN 1681-116X. Ukr. socìum, 4(67), 80–102.

- Belmar, J., Stuardo, V., Folch, C., Carvajal, B., Clunes, M. J., Montoliu, A., & Casabona, J. (2018). A typology of female sex work in the metropolitan region of Santiago, Chile. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(4), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1355478

- Benoit, C., Jansson, S. M., Smith, M., & Flagg, J. (2018). Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652

- Benoit, C., Maurice, R., Abel, G., Smith, M., Jansson, M., Healey, P., & Magnuson, D. (2019). ‘I dodged the stigma bullet’: Canadian sex workers’ situated responses to occupational stigma. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1576226

- Brodeur, A., Lekfuangfu, W. N., & Zylberberg, Y. (2018). War, migration and the origins of the Thai sex industry. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(5), 1540–1576. https://doi-org.uml.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx037

- Bruckert, C., & Parent, C. (2013). The work of sex work. In C. Parent, C. Bruckert, P. Corriveau, M. N. Mensah, & L. Toupin (Eds.), Sex work: Rethinking the job, respecting the workers (pp. 57–80). UBC Press.

- Bruckert, C., Parent, C., & Robitaille, P. (2003). Erotic service/erotic dance establishments: Two types of marginalized labor. The Law Commission on Canada.

- Buzdugan, R., Copas, A., Moses, S., Blanchard, J., Isac, S., Ramesh, B. M., Washington, R., Halli, S. S., & Cowan, F. M. (2010). Devising a female sex work typology using data from Karnataka, India. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(2), 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp351

- Buzdugan, R., Halli, S., & Cowan, F. (2009). The female sex work typology in India in the context of HIV/AIDS. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 14(6), 673–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02278.x

- Cabral, A., & Gemmell, N. (2018). Estimating self-employment income-gaps from register and survey data: Evidence for New Zealand (Working Paper Series 7625). Victoria University of Wellington, Chair in Public Finance. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/7625

- Chen, Y., Li, X., Shen, Z., Zhou, Y., Tang, Z., & Huedo-Medina, T. (2015). Contextual influence on condom use in commercial sex venues: A multi-level analysis among female sex workers and gatekeepers in Guangxi, China. Social Science Research, 52, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.01.010

- Cheuk, E., Isac, S., Musyoki, H., Pickles, M., Bhattacharjee, P., Gichangi, P., Lorway, R., Mishra, S., Blanchard, J., & Becker, M. (2019). Informing HIV prevention programs for adolescent girls and young women: A modified approach to programmatic mapping and key population size estimation. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(2), e11196. https://doi.org/10.2196/11196

- Choi, S., Chen, K., & Jiang, Z. (2008). Client-perpetuated violence and condom failure among female sex workers in southwestern China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 35(2), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815407c3

- Decker, M., McCauley, H., Phuengsamran, D., Janyam, S., Seage, G., 3rd, & Silverman, J. (2010). Violence victimisation, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection symptoms among female sex workers in Thailand. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 86(3), 236–240. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2009.037846

- Decker, M., Wirtz, A., Baral, S., Peryshkina, A., Mogilnyi, V., Weber, R., Stachowiak, J., Go, V., & Beyrer, C. (2012). Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 88(4), 278–283. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2011-050171

- Deering, K., Amin, A., Shoveller, J., Nesbitt, A., Garcia-Moreno, C., Duff, P., Argento, E., & Shannon, K. (2014). A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. American Journal of Public Health, 104(5), e42–e54. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301909

- Deering, K., Lyons, T., Feng, C., Nosyk, B., Strathdee, S., Montaner, J., & Shannon, K. (2013). Client demands for unsafe sex: The socio-economic risk environment for HIV among street and off-street sex workers. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63(4), 522. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182968d39

- Demchenko, I., Bulyha, N., Pyvovarova, N., Artukh, O., Yaremchuk, M., Dorofieieva, N., & Isaieva, N. (2019). Decriminalization of sex work in Ukraine: Public opinion analysis, estimation of difficulties and possibilities. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https://legalifeukraine.com/en/sexwork-en/decriminalization-of-sex-work-in-ukraine-public-opinion-analysis-estimation-of-difficulties-and-possibilities-3420/

- de Wildt, R. (2019). Post-war prostitution: Human trafficking and peacekeeping in Kosovo (Vol. 17). Springer.

- Duff, P., Shoveller, J., Dobrer, S., Ogilvie, G., Montaner, J., Chettiar, J., & Shannon, K. (2015). The relationship between social, policy and physical venue features and social cohesion on condom use for pregnancy prevention among sex workers: A safer indoor work environment scale. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(7), 666–672. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204427

- du Plessis, E., Chevrier, C., Lazarus, L., Reza-Paul, S., Rahman, S. H. U., Ramaiah, M., Avery, L., & Lorway, R. (2020). Pragmatic women: Negotiating sex work, pregnancy, and parenting in Mysore, South India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(10), 1177–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1662946

- Durevall, D., & Lindskog, A. (2015). Intimate partner violence and HIV in ten sub-Saharan African countries: What do the demographic and health surveys tell us? The Lancet Global Health, 3(1), e34–e43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70343-2

- Emmanuel, F., Isac, S., & Blanchard, J. (2013). Using geographical mapping of key vulnerable populations to control the spread of HIV epidemics. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy, 11(5), 451–453. https://doi.org/10.1586/eri.13.33

- Femi-Ajao, O., Kendal, S., & Lovell, K. (2020). A qualitative systematic review of published work on disclosure and help-seeking for domestic violence and abuse among women from ethnic minority populations in the UK. Ethnicity & Health, 25(5), 732–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1447652

- Ferguson, A., Shannon, K., Butler, J., & Goldenberg, S. (2017). A comprehensive review of HIV/STI prevention and sexual and reproductive health services among sex workers in conflict-affected settings: Call for an evidence- and rights-based approach in the humanitarian response. Conflict and Health, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-017-0124-y

- Fisher, B., Daigle, L., Cullen, F., & Turner, M. (2003). Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: Results from a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30(1), 6–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854802239161

- Goldenberg, S., Duff, P., & Krusi, A. (2015). Work environments and HIV prevention: A qualitative review and meta-synthesis of sex worker narratives. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2491-x

- Goldenberg, S., Jiménez, T., Brouwer, K., Miranda, S., & Silverman, J. (2018). Influence of indoor work environments on health, safety, and human rights among migrant sex workers at the Guatemala-Mexico border: A call for occupational health and safety interventions. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0149-3

- Goldenberg, S., Strathdee, S., Gallardo, M., Nguyen, L., Lozada, R., Semple, S., & Patterson, T. (2011). How important are venue-based HIV risks among male clients of female sex workers? A mixed methods analysis of the risk environment in nightlife venues in Tijuana, Mexico. Health & Place, 17(3), 748–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.01.012

- Harcourt, C., & Donovan, B. (2005). The many faces of sex work. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81(3), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2004.012468

- Havlik, P., Kochnev, A., & Pindyuk, O. (2020). Economic challenges and costs of reintegrating the Donbas region in Ukraine (wiiw Research report, no. 447). Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/223097

- Holt, E. (2018). Conflict in Ukraine and a ticking bomb of HIV. The Lancet HIV, 5(6), e273–e274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30106-1

- Hong, Y., & Li, X. (2011). Typology of female sex workers and association with HIV risks: Evidence from China. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 87(1), 233–233. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050108.311

- Hurst, E., Li, G., & Pugsley, B. (2014). Are household surveys like tax forms? Evidence from income underreporting of the self-employed. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00363

- Ikpeazu, A., Momah-Haruna, A., Mari, B., Thompson, L., Ogungbemi, K., Daniel, U., Aboki, H., Isac, S., Gorgens, M., Mziray, E., & Njie, N. (2014). An appraisal of female sex work in Nigeria – Implications for designing and scaling up HIV prevention programmes. PLoS One, 9(8), e103619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103619.

- Kazatchkine, M. (2017). Towards a new health diplomacy in eastern Ukraine. The Lancet HIV, 4(3), e99–e101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30019-X

- Lazarus, L., Deering, K., Nabess, R., Gibson, K., Tyndall, M., & Shannon, K. (2012). Occupational stigma as a primary barrier to health care for street-based sex workers in Canada. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.628411

- Lewis, J., Maticka-Tyndale, E., Shaver, F., & Schramm, H. (2005). Managing risk and safety on the job: The experiences of Canadian sex workers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 17(1-2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v17n01_09

- Lorway, R., Khan, S., Chevrier, C., Huynh, A., Zhang, J., Ma, X., Blanchard, J., & Yu, N. (2017). Sex work in geographic perspective: A multi-disciplinary approach to mapping and understanding female sex work venues in Southwest China. Global Public Health, 12(5), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1123748

- Lowman, J. (2000). Violence and the outlaw status of (street) prostitution in Canada. Violence Against Women, 6(9), 987–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778010022182245

- Lyons, C., Grosso, A., Drame, F., Ketende, S., Diouf, D., Ba, I., Shannon, K., Ezouatchi, R., Bamba, A., Kouame, A., & Baral, S. (2017). Physical and sexual violence affecting female sex workers in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: Prevalence, and the relationship with the work environment, HIV and access to health services. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 75(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001310

- Lyons, C., Schwartz, S., Murray, S., Shannon, K., Diouf, D., Mothopeng, T., Kouanda, S., Simplice, A., Kouame, A., Mnisi, Z., & Tamoufe, U. (2020). The role of sex work laws and stigmas in increasing HIV risks among sex workers. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi-org.uml.idm.oclc.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14593-6

- Maistat, L., Kravchenko, N., & Reddy, A. (2017). Hepatitis c in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A survey of epidemiology, treatment access and civil society activity in eleven countries. Hepatology, Medicine and Policy, 2(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41124-017-0026-z

- McBride, B., Goldenberg, S. M., Murphy, A., Wu, S., Braschel, M., Krüsi, A., & Shannon, K. (2019). Third parties (venue owners, managers, security, etc.) and access to occupational health and safety among sex workers in a Canadian setting: 2010–2016. American Journal of Public Health, 109(5), 792–798. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.304994

- McClarty, L., Balakireva, O., Pavlova, D., Cheuk, E., Nguien, N., & Pickles, M. (2018). Estimating female sex workers’ early HIV and hepatitis C risk in Dnipro, Ukraine: Implications for epidemic control (transitions study): Summary report of early findings.

- McGrath, N., Eaton, J. W., Newell, M. L., & Hosegood, V. (2015). Migration, sexual behaviour, and HIV risk: A general population cohort in rural South Africa. The Lancet HIV, 2(6), e252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00045-4

- Mishra, S., Moses, S., Hanumaiah, P. K., Washington, R., Alary, M., Ramesh, B. M., Isac, S., & Blanchard, J. (2009). Sex work, syphilis, and seeking treatment: An opportunity for intervention in HIV prevention programming in Karnataka, South India. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 36(3), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d64e6

- Mock, N. B., Duale, S., Brown, L. F., Mathys, E., O'Maonaigh, H. C., Abul-Husn, N. K., & Elliot, S. (2004). Conflict and HIV: A framework for risk assessment to prevent HIV in conflict affected settings in Africa. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 1(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-7622-1-6

- Moore, J., Stinson, L., & Welniak, E. (2000). Income measurement error in surveys: A review. Journal of Official Statistics – Stockholm, 16(4), 331–362.

- Nelson, E. U. E. (2020). The lived experience of violence and health-related risks among street sex workers in Uyo, Nigeria. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(9), 1018–1031. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1648872

- Nizhnikau, R., & Moshes, A. (2016). Three years after Euromaiden: Is Ukraine still on the reform track? (FIIA Briefing Paper). https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/three-years-after-euromaidan

- Novakova, Z. (2017). Four dimensions of societal transformation An Introduction to the problematique of Ukraine. The International Journal of Social Quality, 7(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3167/IJSQ.2017.070202

- Olawore, O., Tobian, A. A., Kagaayi, J., Bazaale, J. M., Nantume, B., Kigozi, G., Nankinga, J., Nalugoda, F., Nakigozi, G., Kigozi, G., & Gray, R. H. (2018). Migration and risk of HIV acquisition in Rakai, Uganda: A population-based cohort study. The Lancet HIV, 5(4), e181–e189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30009-2

- Pando, M. A., Coloccini, R. S., Reynaga, E., Fermepin, M. R., Vaulet, L. G., Kochel, T. J., Montano, S. M., & Avila, M. M. (2013). Violence as a barrier for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Argentina. PLoS One, 8(1), e54147. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054147.

- Pannetier, J., Ravalihasy, A., Lydié, N., Lert, F., du Loû, A. D., & Group, P. S. (2018). Prevalence and circumstances of forced sex and post-migration HIV acquisition in Sub-Saharan African migrant women in France: An analysis of the ANRS-PARCOURS retrospective population-based study. The Lancet Public Health, 3(1), e16–e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30211-6

- Peitzmeier, S., Wirtz, A., Peryshkina, A., Sherman, S., Colantuoni, E., Beyrer, C., & Decker, M. (2020). Associations between violence and HIV risk behaviors differ by perpetrator among Russian sex workers. AIDS and Behavior, 24(3), 812–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02668-5

- Pissarides, C., & Weber, G. (1989). An expenditure-based estimate of Britain’s black economy. Journal of Public Economics, 39(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(89)90052-2

- Platt, L., Elmes, J., Stevenson, L., Holt, V., Rolles, S., & Stuart, R. (2020). Sex workers must not be forgotten in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet, 396(10243), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31033-3

- Platt, L., Grenfell, P., Meiksin, R., Elmes, J., Sherman, S., Sanders, T., Mwangi, P., & Crago, A. (2018). Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine, 15(12), e1002680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002680

- Puradiredja, D., & Coast, E. (2012). Transactional sex risk across a typology of rural and urban female sex workers in Indonesia: A mixed methods study. PLoS One, 7(12), e52858. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052858

- Pyvovarova, N., & Artiukh, O. R. (2020). Change of legal status of sex work in Ukraine: Public opinion, opinion of sex workers (sociological perspective). Ukr. socìum, 3(74), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.15407/socium2020.03.124

- Rhodes, T., Ball, A., Stimson, G., Kobyshcha, Y., Fitch, C., Pokrovsky, V., Bezruchenko-Novachuk, M., Burrows, D., Renton, A., & Andrushchak, L. (2002). HIV infection associated with drug injecting in the newly independent states, Eastern Europe: The social and economic context of epidemics. Addiction, 94(9), 1323. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913235.x

- Rhodes, T., Simić, M., Baroš, S., Platt, L., & Žikić, B. (2008). Police violence and sexual risk among female and transvestite sex workers in Serbia: Qualitative study. BMJ, 337(jul30 2), a811. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a811

- Sereda, Y., & Sazonova, Y. (2016). Monitoring of behaviour and HIV prevalence among sex workers: Analytical report. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://aph.org.ua/

- Shannon, K., & Csete, J. (2010). Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. JAMA, 304(5), 573–574. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1090

- Shannon, K., Strathdee, S., Goldenberg, S., Duff, P., Mwangi, P., Rusakova, M., Reza-Paul, S., Lau, J., Deering, K., Pickels, M., & Boily, M. (2015). Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. The Lancet, 385(9962), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4

- Sherman, S., Footer, K., Illangasekare, S., Clark, E., Pearson, E., & Decker, M. (2015). “What makes you think you have special privileges because you are a police officer?” A qualitative exploration of police's role in the risk environment of female sex workers. AIDS Care, 27(4), 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.970504

- Swain, S., Saggurti, N., Battala, M., Verma, R., & Jain, A. (2011). Experience of violence and adverse reproductive health outcomes, HIV risks among mobile female sex workers in India. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 357. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-357

- Szwarcwald, C., Damacena, G., de Souza-Júnior, P., Guimarães, M., de Almeida, W., de Souza Ferreira, A., da Costa Ferreira-Júnior, O., & Dourado, I. (2018). Factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers in Brazil. Medicine, 97(1), S54–S61. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009013

- Tokar, A., Osborne, J., Slobodianiuk, K., Essink, D., Lazarus, J., & Broerse, J. (2019). ‘Virus carriers’ and HIV testing: Navigating Ukraine’s HIV policies and programming for female sex workers. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0415-4

- Van der Meulen, E. (2010). Ten: Illegal lives, loves, and work: How the criminalization of procuring affects sex workers in Canada. Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, 8 (Fall 2010), 217–240.

- Vasylyeva, T. I., Liulchuk, M., Friedman, S. R., Sazonova, I., Faria, N. R., Katzourakis, A., Babii, N., Scherbinska, A., Thézé, J., Pybus, O. G., & Smyrnov, P. (2018). Molecular epidemiology reveals the role of war in the spread of HIV in Ukraine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(5), 1051–1056. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701447115

- Vitek, C., Čakalo, J., Kruglov, Y., Dumchev, K., Salyuk, T., Božičević, I., Baughman, A., Spindler, H., Martsynovska, V., Kobyshcha, Y., Abdul-Quader, A., & Rutherford, G. (2014). Slowing of the HIV epidemic in Ukraine: Evidence from case reporting and key population surveys, 2005–2012. PLoS One, 9(9), e103657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103657.

- Wirtz, A., Schwartz, S., Ketende, S., Anato, S., Nadedjo, F., Ouedraogo, H., Ky-Zerbo, O., Pitche, V., Grosso, A., Papworth, E., & Baral, S. (2015). Sexual violence, condom negotiation, and condom use in the context of sex work: Results from two west African countries. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 68(Supplement 2), S171–S179. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000451

- Yi, H., Mantell, J., Wu, R., Lu, Z., Zeng, J., & Wan, Y. (2010). A profile of HIV risk factors in the context of sex work environments among migrant female sex workers in Beijing, China. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 15(2), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548501003623914