ABSTRACT

COVAX, the vaccines pillar of the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), has been promoted as ‘the only global solution' to vaccine equity and ending the Covid-19 pandemic. ACT-A and COVAX build on the public-private partnership (PPP) model that dominates global health governance, but take it to a new level, constituting an experimental form that we call the ‘super-PPP'. Based on an analysis of COVAX's governance structure and its difficulties in achieving its aims, we identify several features of the super-PPP model. First, it aims to coordinate the fragmented global health field by bringing together existing PPPs in an extraordinarily complex Russian Matryoshka doll-like structure. Second, it attempts to scale up a governance model designed for donor-dependent countries to tackle a health crisis affecting the entire world, pitting it against the self-interest of its wealthiest government partners. Third, the super-PPP's structural complexity obscures the vast differences between constituent partners, giving pharmaceutical corporations substantial power and making public representation, transparency, and accountability elusive. As a super-PPP, COVAX reproduces and amplifies challenges associated with the established PPPs it incorporates. COVAX's limited success has sparked a crisis of legitimacy for the voluntary, charity-based partnership model in global health, raising questions about its future.

Introduction

COVAX and the Covid-19 pandemic

COVAX was established as the vaccines pillar of the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), which describes itself as ‘a ground-breaking global collaboration to accelerate the development, production, and equitable access to Covid-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines’ (Gavi, Citation2020e). COVAX’s original aim was to secure access to a diverse portfolio of vaccine doses for at least 20% of participating countries’ populations, delivered as soon as they became available, in order to end the acute phase of the pandemic and rebuild economies (WHO, Citation2021a). Its leaders claimed it was ‘the only global solution’ for vaccine equity, i.e. the fair distribution of vaccines to all populations (Gavi, Citation2020e).

COVAX quickly helped establish normative acceptance of the need for a global collaboration to accelerate vaccine development and access, mobilising resources from government and philanthropic sources to stimulate research and development (R&D) and facilitating large-scale vaccine procurement and distribution. COVAX delivered its first dose in Ghana on 24 February 2021 – less than three months after the UK became the world’s first country to start a mass vaccination campaign. It reached over 100 countries with vaccine doses within 42 days, many of which would not otherwise have gained access to vaccines (WHO, Citation2021b).

However, COVAX soon turned out to be insufficient to bring about global vaccine equity. At the time of writing, in June 2021, COVAX had distributed less than 5% of its 2 billion target (89 million vaccine doses) (Covax, Citation2021). Meanwhile, 90% of Covid-19 vaccines had been administered in the richest G20 countries, leading Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), to conclude that, ‘the rapid development of Covid-19 vaccines is a triumph of science, but their inequitable distribution is a failure of humanity’ (UN, Citation2021).

In this paper, we argue that COVAX’s failure so far to ensure global vaccine equity is not merely the result of outside forces but results from limitations related to its governance structure. As we show, COVAX is not just another global ‘collaboration’; It is an extraordinarily complex multistakeholder public-private partnership (PPP), co-led by existing PPPs as one pillar of an even more complex PPP, ACT-A. We show that it constitutes an experimental institutional form for dealing with global health crises that we call the ‘super-PPP’, which structurally resembles a series of Russian Matryoshka dolls of decreasing sizes nested inside each other.

PPPs: The main governance mechanism for addressing global health challenges

PPPs can be thought of as lasting institutional arrangements in which private and public sector entities share decision-making power (Andonova, Citation2017; Buse & Harmer, Citation2004, Citation2007; Rushton & Williams, Citation2011). The rise of PPPs over the past two decades marks a revolution in the governance of global health, away from ‘international’ health cooperation between nation states through forums and channels set-up by multilateral organisations such as the WHO or the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), towards a much more fragmented field of ‘global’ health incorporating non-state actors (Brown et al., Citation2006). Philanthropic foundations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and businesses played a key role in implementing international health programmes in the twentieth century, yet overall responsibility and coordinating power lay with public entities (Birn, Citation2006). This was in line with the post-World War II multilateral cooperation system of the United Nations, centred on nation states. Yet, at the end of the 1990s, non-state actors radically gained power, their influence formalised through the establishment of global health PPPs. This shift was driven by the systemic underfunding of existing national and multilateral health institutions and the ideology of new public management, which promoted modelling public institutions on actual and perceived virtues of the private sector.

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and the Global Fund to fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, established in 2000 and 2002 respectively, quickly became models for public-private cooperation to address health challenges affecting poor countries, often with substantial philanthropic support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In Gavi’s own words, it ‘combines the technical expertise of the development community with the business know-how of the private sector’ (Gavi, Citation2020a). Today’s global health PPPs vary significantly in size, budget, and institutional structure. For example, both the Global Fund and Gavi are institutionalised as their own legal entities, with independent secretariats, a large degree of autonomy and substantial budgets, and influence rivalling that of the WHO. Other partnerships are less autonomous, and may be hosted by intergovernmental agencies, sometimes as mere programmes (Andonova, Citation2017). Though most focus on providing access to health technologies in low-income countries, newer partnerships, like CEPI, which funds vaccine development to stop future epidemics, espouse the notion of ‘global public goods’ to emphasise a joint benefit for countries everywhere.

As a governance ‘innovation’, PPPs have raised unprecedented political will and resources to address neglected health challenges, bringing with them a focus on individual diseases, a business ethos prioritising measurable results and a penchant for technological solutions such as vaccines (Birn, Citation2005). While also associated with the promotion of ‘vertical’ disease-specific initiatives that erode broader health system development and donor-driven decision-making challenging ‘country ownership’, they are generally considered an efficient way of achieving health targets (WHO, Citation2009). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 called for more multi-stakeholder partnerships (goal #17), providing the PPP model with even greater international endorsement (UN, Citation2015). It is thus not surprising that it became the blueprint for global cooperation during the Covid-19 pandemic too.

The Covid-19 pandemic as the age of the super-PPP

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck, global health policy makers deployed considerable political and diplomatic efforts to institute global coordination mechanisms. From the start, the Gates Foundation and the World Bank argued that this could not be achieved without the close involvement of existing global health PPPs and the private sector (Yamey et al. Citation2020). This led them to draft plans for another global PPP for Covid-19 medical technologies, ACT-A, which was announced at a G20-meeting on 24 April 2020, by the European Commission (EC) and the Gates Foundation, with separate pillars for diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines and a health systems ‘connector’. Many world leaders quickly embraced this development. Writing in The Guardian in June 2020, Gro Harlem Brundtland, former Director General of the WHO, and Elizabeth Cousens, President of the UN Foundation, called for us ‘to embrace the unprecedented scale of partnership between governments, business, international organisations such as the UN and WHO, non-profits, and scientists and researchers’, seeing them as essential to ending the pandemic (The Guardian, Citation2020).

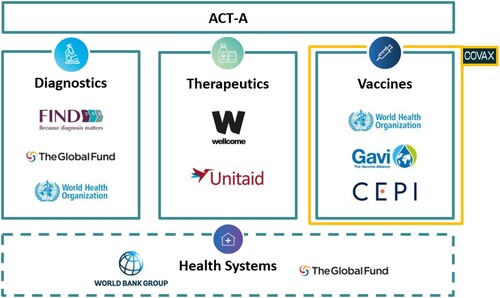

In bringing together actors from the public and private sectors to focus squarely on technological solutions (diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines) for a single disease, ACT-A has the key features normally associated with PPPs. However, we argue that its creation signals a new phase or iteration of this model, as the first example of an ‘alliance’ of major established PPPs intended to benefit not just developing countries, but the entire world. Under ACT-A’s umbrella structure, several established PPPs have responsibility for overseeing different pillars, drawing on their established ‘comparative advantage’: Gavi and CEPI the vaccines pillar; Unitaid the therapeutics pillar; Find the diagnostics pillar; and The Global Fund the crosscutting health systems connector. These PPPs work alongside multilateral organisations (WHO, UNICEF, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Bank), as well as the largest global health philanthropic foundations (the Wellcome Trust, the Gates Foundation) and governments to ‘accelerate’ the development and equitable distribution of Covid-19 tools ().

Figure 1. COVAX within ACT-A’s structure (simplified). Source: ACT-A Accelerator Impact Report Summary, available at https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/act-accelerator-impact-report-summary.

How does global governance change when various PPPs are combined and set to work together at this unprecedented scale and scope? Which dilemmas arise? What are the strengths and weaknesses of the experimental form we call a super-PPP? Below, we address these questions by honing in on ACT-A’s vaccines pillar COVAX, its most prominent and best-funded pillar. Based on an analysis of COVAX’s governance structure as a super-PPP, we unpack how this structure has enabled national and corporate interests to take precedence over genuine ‘partnership’, challenging COVAX’s vision of global cooperation. Specifically, we discuss how COVAX failed to institute safeguards against its government partners pursuing policies that directly undermine its goals, namely ‘vaccine nationalism,’ i.e. privileging vaccination on a national scale to the detriment of multilateral vaccine efforts, and ‘vaccine diplomacy’, sharing excess vaccine doses in the pursuit of direct political gains. Moreover, we show how its voluntary, partnership-based model has given too much power to pharmaceutical companies, doing little to dissuade them from using their privileged position to boost profit and shareholder value by keeping vaccine supply limited. Rather than constituting mere outside forces, however, we argue that these challenges were enabled by COVAX’s institutional design and the nature of the super-PPP model itself.

Based on this, we identify core features of the super-PPP model. First, it aims to coordinate a fragmented global health field by bringing together existing PPPs under one umbrella, making public representation, transparency, and accountability elusive. Second, it attempts to scale up a governance model designed for donor-dependent countries to tackle a health challenge affecting the entire world, pitting it against the immediate self-interest of its wealthiest partners. Third, it is so complex that it obscures the vast differences in mandate and public accountability between its constituent partners, imbuing corporate partners with substantial power.

In conclusion, we discuss how the limited success of COVAX has created a crisis of legitimacy for the notion that voluntary partnership between public and private actors is the obvious solution to global health crises. A growing contingency of civil society actors and world leaders reject its charity-based model as a sign of complicity between wealthy country governments and ‘Big Pharma’, and advocate instead for alternative solutions, including for a ‘People’s Vaccine’. While focused on the governance of global health, our analysis holds lessons for other highly fragmented and partnership-dominated governance fields such as nutrition and environment (Andonova, Citation2017).

Methods

This paper is part of a Research Council of Norway-funded project that examines the rise of new forms of cooperation between public authorities and private actors in pandemic preparedness and response, focusing on Norway. Norway plays an important role in promoting such cooperation. It hosts CEPI and was central to forming the COVAX initiative and co-leads (with South Africa) the ACT-A Facilitation Council, and plays a significant role in Gavi, with the current Norwegian Ambassador of Global Health being a Gavi Board member. We draw on data from three main sources: an analysis of COVAX’s governance structure; a literature and media review; and in-depth interviews with individuals associated with COVAX.

Our quantitative analysis of the institutional and demographic make-up of COVAX was conducted in March 2021, using publicly available datasets from Gavi’s website on COVAX, notably COVAX’s Structures and Principles document (Gavi, Citation2021b). We analysed the level of representation of different institutions and countries across COVAX’s workstreams and committees. To identify whether a country was self-financing, ‘potentially self-financing’ or eligible for donor subsidy, Gavi’s source was used (Gavi, Citation2021a). Where individuals or countries were listed as representatives of certain workstreams, we conducted a Google search to identify individuals’ roles, for example, whether a representative was an MP, a health minister, or a private businessperson in their country.

Our media and literature review focused on COVAX documents and press reports, and expert analysis of COVAX published between May 2020 and July 2021 in leading international newspapers and periodicals (e.g. The New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, Le Monde, The Atlantic), editorials in scientific journals (e.g. The Lancet) and specialist online reporting (e.g. Geneva Health Files, Development Today, Devex). We also observed evolving debates about COVAX, gleaned from expert and public consultations, webinars, exchanges with civil society organisations and social media discussions.

We interviewed 26 prominent actors involved in COVAX or in the wider global pandemic response between September 2020 and February 2021. Interviewees included CEPI, Gavi and COVAX staff, government ministers and diplomats involved in ACT-A, public health authorities, pharmaceutical company representatives and members of international civil society organisations involved in debates about vaccine equity. This includes 10 Norwegian actors directly involved in ACT-A and COVAX. All interviews were recorded with interviewees’ consent and transcribed verbatim. We approached the Gates Foundation multiple times for an interview given their significant role in shaping both ACT-A and COVAX (The New Republic, Citation2021) but were denied and only received a succinct email reply to our questions.

Our sources allow us to provide a first overview of the emergence of COVAX and its super-PPP structure, but it is beyond the scope of the paper to consider in-depth the internal political processes within each constituent organisation, or the interaction between ACT-A’s different pillars.

COVAX’s governance structure as a super-PPP

Fifteen years ago, Buse and Harmer identified as a key shortcoming of global health PPPs their contested legitimacy, due to private sector involvement, and failure to provide legitimate stakeholders a voice in decision-making, most notably constituencies from low- and middle-income countries (LMICS) and civil society, who are under-represented on governing bodies relative to the corporate sector (Buse & Harmer, Citation2004, Citation2007). In the years since, PPPs have made piecemeal efforts to redress some of these imbalances by increasing the diversity of board members and enlisting civil society ‘engagement’ through formal representation for example (Puyvallée & Storeng, Citation2017; Storeng, Citation2014; Storeng & de Bengy Puyvallée, Citation2018). Nevertheless, our analysis shows that COVAX reproduces at the super-PPP scale many of the issues identified in previous analyses of the PPPs it incorporates, including dominance by wealthy governments and philanthropic foundations, significant pharmaceutical company influence, and circumscribed roles for the WHO or other UN agencies (Shiffman, Citation2017). It even amplifies these challenges, because they are in part hidden within an overly complex governance structure.

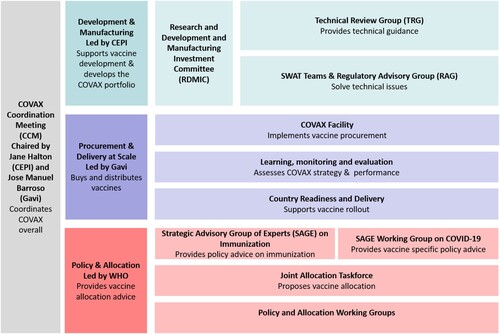

COVAX is loosely organised but institutionally complex (). Its structure is in flux, and we describe its makeup at the time of writing, in June 2021, roughly one year after its formation. It combines Gavi, CEPI and the WHO as ‘co-leads’, with UNICEF and PAHO as ‘implementing partners’. It does not have its own board or its own budget. Instead, donations to COVAX are funnelled to its leading entities, most notably Gavi and CEPI, who by late June 2021 had received 80% and 13% of its mostly public donations respectively (WHO, Citation2021). COVAX’s main decision-making forum is the ‘COVAX Coordination Meeting’ (CCM), co-chaired by CEPI and Gavi board chairs Jane Halton and Jose Manuel Barroso. Halton and Barroso are formally accountable to their respective boards rather than to COVAX partners. Permanent CCM members include the co-leads’ executive directors (CEPI’s Richard Hatchett, Gavi’s Seth Berkley and WHO’s Chief Scientist Soumya Swaminathan); workstream leaders (listed below), two representatives of the pharmaceutical industry, a member of UNICEF and a civil society representative.

COVAX has three main workstreams each overseen by a co-lead organisation and with both direct and indirect ties to the pharmaceutical industry (). CEPI oversees the ‘Development and Manufacturing’ workstream that decides which vaccine candidates are worthy of financial support and subsequent procurement. This workstream is led by CEPI’s Melanie Saville, who previously worked for the UK’s National Health Service and various pharmaceutical companies. Voting members in this workstream’s main decision-making body, called the ‘Research and Development and Manufacturing Investment Committee’, include representatives of Gavi, CEPI, the Gates Foundation and the Africa CDC, as well as five individuals who are venture capitalists and current and former pharmaceutical company executives. Civil society is not represented on this committee.

Gavi leads COVAX’s second workstream for vaccine ‘Procurement and Delivery at Scale’ with Aurélia Nguyen, a former pharmaceutical executive and subsequent Gavi employee as managing director. It is based within the Gavi Secretariat and the Gavi Board has ultimate responsibility for the decisions and implementation of this workstream. The final workstream, which focuses on vaccine ‘Policy and Allocation’, is led by WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization. The workstream advises other workstreams, as well as the WHO and its member states on vaccine science and ethics. It consists of members of universities, public health bodies, UN organisations, CEPI, Gavi, the Gates Foundation and NGOs. COVAX’s three workstreams are further divided into 31 sub-committees or working groups. The top five institutions represented as chairs of these committees are WHO, CEPI, Gavi, UNICEF and the Gates Foundation.

Figure 2. COVAX’s three workstreams (simplified & subject to change due to COVAX’s evolving nature). Source: Gavi (Citation2021b).

Publicly available documents list 464 individuals as part of COVAX’s governance structure (Gavi, Citation2021b). Only 63 (14%) of these represent governments. Remarkably, an overwhelming majority of country representatives (81%) are from self-financing countries (HICs and UMICs). Industry representatives account for 6% of COVAX listed participants, and only 16 individuals (3.4%) represent NGOs or civil society. There is no publicly available information about how committee members are selected, and several sub-committees have been established on paper only, as their membership is yet ‘to be determined’.

While Gavi, CEPI and the Gates Foundation strongly influence decision making within COVAX by leading and dominating the key working groups where decisions are taken, UN agencies widely populate working groups and sub-committees, but seem to hold more marginal normative and technical roles. Like the PPPs it incorporates, COVAX was also initially reluctant to include civil society in its decision-making structures. Ahead of Gavi’s board meeting on 30 July 2020, over 175 civil society organisations and individuals, including the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access Campaign, wrote an open letter to the Gavi board noting the complete absence of civil society in COVAX and demanding better representation (MSF, Citation2020). By end of October 2020, however, Gavi welcomed civil society representatives to COVAX working groups, including from MSF, Save the Children, the International Rescue Committee (Gavi, Citation2020b).

In the next section, we analyse how despite COVAX’s efforts to improve representation, its complex and fragmented governance structure has enabled national and corporate interests to take precedence over the genuine partnership.

COVAX and vaccine nationalism

Trying to cater to wealthy and poor countries alike, COVAX invited HICs and UMICs to join a ‘buyers’ club’ called the COVAX Facility and purchase a shared portfolio of vaccines (Eccleston-Turner & Upton, Citation2021). This promised them lower vaccine prices and a reduction of all kinds of risks to do with vaccine development and procurement (Stein, Citation2021). 92 low income and lower middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs) were grouped into a separate purchasing club called the COVAX Advance Market Commitment (Gavi COVAX AMC), subsidised by donors’ overseas development budgets, a model originally developed for purchasing pneumococcal vaccines for low-income countries eligible for Gavi support.

Although public funders have supported COVAX generously, COVAX simultaneously allowed its members to strike bilateral vaccine purchase agreements that undermined its supply and reduced its purchasing power. Shortly after COVAX was created, the US, Canada, the EU (European Union), the UK, Israel, and oil-rich Gulf countries engaged in a race to sign bilateral deals with Western pharmaceutical companies, while China, Russia and India secured early contracts with their own domestic vaccine industries. As in previous pandemic outbreaks (Eccleston-Turner & Upton, Citation2021), COVAX’s high-income country partners used advance purchase agreements to secure early and extensive vaccine access for domestic populations. They paid higher prices per vaccine dose than COVAX was able to, often combined with legal concessions, vast corporate subsidies, unforeseen public data provision to vaccine companies and sometimes export restrictions. They bought up global vaccine production capacity even before COVAX secured its first financial instalments and was fit to start negotiation with industry. By November 2020, a widely reported analysis found that HICs and UMICs had already reserved 3.8 billion doses, with options for 5 billion more, even before any vaccine candidates had been approved (Duke Global Health Innovation Centre, Citation2021). This was rapidly condemned by global health leaders within the WHO and the African Union as a form of ‘vaccine nationalism’ and a betrayal of COVAX’s vision of vaccine equity.

Some high- and middle-income countries (e.g. Canada, New Zealand, Japan, Australia South Africa, and Mexico) bought vaccine options from COVAX’s self-financing window alongside their bilateral deals. Within Europe however, only the UK and Norway did. ‘Team Europe’ (the European Commission (EC) and some EU member states) approached vaccine procurement in a paradoxical manner by first taking the initiative to launch COVAX, but then deciding not to buy their vaccines through the global procurement mechanism. Opting instead to develop a joint EU procurement mechanism in June 2020 (Schaik et al., Citation2020), ‘Team Europe’ only supported the COVAX Gavi AMC fund for LICs and LMICs. In the words of a middle-income country diplomat whom we interviewed in the summer of 2020:

[Europeans] made a huge effort in this pledging event in May [2020] […] with all heads of state and everybody giving this declarations or solidarity, pledging millions and billions of dollars. This whole event was based on this idea of solidarity and equitable universal access to the vaccine. And very soon after that, the very same countries that led that pledging event broke the agreement and went their own way. I mean they betrayed their own leadership […] in my opinion that was very serious, that was a big treason, a big betrayal of multilateralism.

The concessions that COVAX made to its self-financing country members must be seen in light of its struggle to garner support from the world’s major geopolitical powers. ‘Team Europe’ was an early sponsor and promoter, along with Japan, the UK, Canada, and Norway, which was appointed co-chair of ACT-A’s Facilitation Council together with South Africa. However, the US under President Donald Trump refused to join COVAX, pursuing instead an ‘America First’ policy to vaccine development and procurement through its own domestic PPP, Operation Warpspeed. It was only once President Biden was inaugurated in 2021, that the US joined COVAX and became its single biggest donor, followed by ‘Team Europe’, Japan, the UK, Canada, and Norway. Together they account for around 89% of ACT-A’s public funding commitments (WHO, Citation2021).

Individual countries justified their decision to purchase vaccines directly from manufacturers rather than through COVAX with reference to the initiative’s slow start (it took over four months for contract negotiations to begin as countries first had to join and fund COVAX), their responsibilities to prioritise their own populations, and claims that doing so was not at odds with showing global solidarity. ‘Team Europe’, for example, defended itself against accusations of vaccine nationalism by pointing to its substantial financial pledges to the Gavi COVAX AMC and to the fact that it had exported over half of the vaccines produced in its territory by mid-2021 (EEAS, Citation2020). This contrasts with the US, which only lifted export bans on vaccines and essential vaccine components in May 2021, and the UK, which, at the time of writing, has not exported any domestically produced vaccines (Development Today, Citation2021a).

In practice, wealthy countries' vaccine purchasing outside of COVAX meant that the initiative quickly became, in the eyes of global health leaders, commentators and its European founders, reduced from a global procurement mechanism to an aid project for subsidising vaccine purchase for poor countries. This helps to explain why Canada, as the first G7 country to purchase vaccines through COVAX in February 2021, was branded a ‘vaccine pirate’ stealing from the poor, even though it was purchasing doses it was technically entitled to as a self-financing member (Toronto Sun, Citation2021; Usher, Citation2021).

Combined with trade restrictions that constrained manufacturing and supply to COVAX, high- and middle-income countries’ hoarding of vaccine doses is now widely acknowledged to have undermined COVAX’s capacity to secure timely access to vaccine doses in sufficient quantities. In January 2021, COVAX nevertheless forecasted that it would roll out 2.3 billion vaccine doses in 2021, with an expected 1.8 billion doses for the 92 lower-income economies (the Gavi COVAX AMC-eligible countries), at least 1.3 billion of these being offered at no cost to their governments (Gavi, Citation2021d). During the spring of 2021, however, COVAX faced huge supply issues after the Serum Institute of India (SII), which it had been heavily relying on for delivery of AstraZeneca vaccines, diverted doses to deal with India’s domestic Covid-19 crisis. Even with large parts of their populations vaccinated, wealthy governments continue to sign advance purchase agreements with vaccine manufacturers for the delivery of booster shots in 2022 and 2023 that compete with COVAX for supply (Reuters, Citation2021b). To our knowledge, these confidential agreements, which are treated as trade secrets still do not include clauses on equitable access.

COVAX and vaccine diplomacy

Without the means to stop its wealthy country partners from pursuing vaccine nationalistic policies, COVAX asked countries who had ‘hoarded’ vaccines to at least share excess vaccine doses with it. The COVAX secretariat developed ‘principles’ for how countries could do so shortly after the first vaccines had been approved for use, in December 2020. These principles entailed five main requirements: vaccines should be safe and efficacious (WHO approved); available early on (preferably first half of 2021); rapidly deployable; unearmarked (to comply with COVAX’s equitable allocation mechanism); and available in high quantities. COVAX also expected donor countries to finance vaccine donations (Gavi, Citation2020d). However, complying with these principles was voluntary, as COVAX lacked any enforcement mechanism and has had to rely on the variable goodwill of its wealthiest partners.

In December 2020, EU countries tried, but failed, to reach agreement on how to implement a plan to share 5% of their reserved doses (Reuters, Citation2020), In January 2021, Norway became the first country to transfer its options to buy vaccines through COVAX to the Gavi COVAX AMC, though this fell short of transferring vaccine doses from its own vaccination programme (Development Today, Citation2021b). In April 2021, France decided to proceed independently despite the absence of a joint EU sharing scheme, announcing an initial donation of 105,600 vaccine doses taken from its vaccination programme to the Gavi COVAX AMC and committing to share 500,000 doses by mid-June, and up to at least 5% of its total doses by the end of 2021 (Gavi, Citation2021c). Throughout spring 2021, the US was heavily criticised for having millions of unused doses in storage (including the AstraZeneca vaccine that was not authorised by the US regulator) (The New York Times, Citation2021). At the G7 meeting of June 2021, President Biden announced that the US would be purchasing 500,000 Pfizer doses to donate to COVAX (The White House, Citation2021) – more than half of the 870 million doses pledged by G7 countries. Critics derided the G7, claiming their pledges were just a drop in the ocean (Buse & Bertram, Citation2021), and noted that the US donation of Pfizer-doses was partly financed by USD 2 billion already pledged to COVAX in February 2021 (Reuters, Citation2021c).

Vaccine donations have been difficult for three main reasons. First, domestic political pressure on leaders to prioritise their own population has been a major impediment. In Norway, for example, the news in early 2021 that the government had transferred its COVAX options to the Gavi COVAX AMC led opposition politicians to argue that these options should have been used for Norway’s domestic vaccination programme (Development Today, 2021). Second, in some cases vaccine producers have imposed contractual conditions and other legal barriers preventing resale or donations of doses. The US decision to ‘loan’ doses of AstraZeneca vaccine to Canada and Mexico in March 2021 for example was reportedly a workaround to evade such conditions (Vanity Fair, Citation2021). Third, and most importantly, countries have opted to donate vaccine doses bilaterally instead of through COVAX to reap diplomatic and geopolitical benefit, an approach that has been coined ‘vaccine diplomacy’ and that directly competes with COVAX. Although initially used as a pejorative term to describe Russia, China, and India’s vaccine donation policies, vaccine diplomacy is also practiced by COVAX’s largest funders – including the US and EU. Besides pledging to channel excess doses through COVAX, the EU has also set up its own vaccine sharing mechanism for allied and neighbouring countries. Potentially in breach of its principles for vaccine donations, COVAX has been forced to accept smaller donations made at the latest stages of wealthy countries’ vaccination programmes and has allowed individual donor countries branding visibility through, for example, national flags on shipments.

Accommodating corporate interests

The lack of safeguards within COVAX against participating countries pursuing policies that undermine its goals is reproduced in its voluntary approach to ‘partnership’ that has struggled to enlist for-profit pharmaceutical companies as genuine ‘partners’. COVAX has accommodated corporate concerns for profit and shareholder value, providing major pharmaceutical companies with a range of push and pull subsidies and amplifying the already substantial public sector financing for R&D and manufacturing both before and during the pandemic (Stein, Citation2021). Public subsidies are widely understood to have been a major driver of the impressive innovation that resulted in several safe and effective vaccines being developed at record speed. According to interviewees, the unprecedented levels of public sector support and the scale of the crisis had led many to hope that ‘industry partners’ would, at least temporarily, forfeit established profit-maximising business practices in the interest of equitable access to the gains of vaccine innovation and marketing. Doing so would strengthen their brands, improve their research, and live up to their frequently altruistic rhetoric.

However, the pharmaceutical industry has not fulfilled these expectations. Oxford University, which developed the vaccine produced by AstraZeneca, originally pledged ‘to donate the rights to its promising coronavirus vaccine to any drugmaker’ through open licensing (Medscape, Citation2020). In the end, AstraZeneca obtained exclusive rights to produce the vaccine, facilitated by the Gates Foundation who provided substantial funding to expand manufacturing capacity and technology transfer to SII, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer (Gavi, Citation2020c, Citation2021e). Although Astra-Zeneca had pledged that it would make its vaccine available ‘at cost’ during the pandemic, its commitment to vaccine equity took a blow after leaked revelations that South Africa has paid more than double the EU price for the AstraZeneca Vaccine, in a bilateral deal outside of the COVAX Facility (The Guardian, Citation2021a). Campaigners who gained access to Astra-Zeneca's contracts have shown that its claim to provide fair prices to developing countries ‘in perpetuity’ is ‘full of holes’ (Fortune, Citation2020).

Nevertheless, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, which signed an advanced purchase agreement with COVAX in May 2021, scored better than mRNA vaccine manufacturers Moderna and Pfizer on rankings such as the ‘vaccine access test’, which grades how world leaders and companies are improving access by supporting global cooperation, including COVAX, and increasing supply for all (One.org, Citation2021). Moderna reserved most of its doses for bilateral deals with wealthy countries, even though it received a grant from CEPI early in the pandemic (January 2020) that included provisions on equitable access, as well as substantial US public funding (The Washington Post, Citation2021). The company only entered a deal with COVAX on 3 May 2020, for up to 500 million doses to be delivered in the second half of 2021 through 2022 – and only after committing to delivering billions of doses first in bilateral deals (Gavi, Citation2021f).

Pfizer, in turn, initially claimed that its motivation for developing a Covid-19 vaccine was to find a medical solution to the crisis, rather than a return on investment. However, in July 2020, its CEO Albert Bourla was quoted saying it was ‘radical’ to suggest pharma should forego profits on future Covid-19 vaccines (Fierce Pharma, Citation2021). Pfizer subsequently reported to the US Securities and Exchange Commission that it expected a profit margin ‘in the high twenty percent’ on its Covid-19 vaccine and over USD 15 billion in revenues for 2021 only (Pfizer, Citation2021). The founders of Pfizer's biotech partner BioNTech became billionaires within just a few months, and BioNTech is reportedly ‘on track to give the German economy an extraordinary boost’, contributing about half a percentage point in German gross domestic product in 2021 (Bloomberg, Citation2021).

Pfizer has consistently prioritised bilateral deals with wealthy country governments and did not agree to supply COVAX before the end of January 2021, initially offering a meagre 40 million doses (2% of its projected 2021 supply) (Reuters, Citation2021a). Pfizer subsequently agreed to sell 500 million doses (for 2021 and 2022) to the US for donation to COVAX ahead of the G7 in June 2021, announcing in a full-page ad in the New York Times that equity was its ‘North Star’. This claim, however, is undermined by Pfizer’s negotiation tactics vis-a-vis poor and middle-income countries who have sought bilateral deals outside of COVAX. The company reportedly demanded that Latin American governments put up state assets, such as embassy building and military bases, as guarantee against the cost of any potential legal cases against the firm (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Citation2021). To justify its high prices relative to manufacturers of other WHO-approved vaccines, Pfizer denied that its vaccine has benefited from public investment, even though its biotech partner BioNTech received substantial EU funding to develop the mRNA technology, and advance purchase agreements offset the company’s risk of scaling up production (Storeng & de Bengy Puyvallée, Citation2020).

Overall, COVAX has had limited success in instilling a commitment among the major vaccine producers to the ideal of ‘partnership’. In fact, pharmaceutical companies have not only prioritised bilateral deals over COVAX but have also artificially constrained supply by refusing to share technology, e.g. via the WHO’s Covid-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) (Project Syndicate, Citation2021). They have exploited their powerful position as the suppliers of essential goods (The Loop, Citation2021) and engaged in rent seeking by lobbying to keep full patent protection despite WTO (World Trade Organization) emergency provisions that would suspend those and enable expanded production (Project Syndicate, Citation2021).

This helps to explain why growing criticism is being directed towards COVAX’s co-leads Gavi and CEPI – and the governments that fund and have a major influence within these institutions – for failing to exercise sufficient leadership in protecting the global public interest (Usher, Citation2021). They have accepted industry demands for secrecy around prices and contracts, making it difficult to ensure accountability for COVAX's spending. Wealthy countries who say they support COVAX have, at the same time, contributed billions in funding to R&D and advance market commitments that offset corporate risk, without imposing sufficiently strong conditions on companies for fair pricing or technology transfer necessary to expand production capacity (Storeng et al., Citation2021). In February 2021, for example, ACT-A co-lead Norway published ‘4 principles for urgent pharma action to combat Covid-19’ (World Economic Forum, Citation2021) that merely made non-committal recommendations for action, but no actual demands, on rapid registration, fair pricing, expanded production and transparency. The recommendations were largely unheeded. Strikingly, a year into COVAX’s existence, even CEPI’s CEO Richard Hatchett conceded that voluntary action is insufficient. At the COVID-19 Global Research & Innovation Forum in May 2021, he said that ‘the great missed opportunity of 2020 is that the funders of vaccine development did not include access provisions in their funding agreements’ and called for different funders to develop common approaches (Geneva Health Files, Citation2021).

Discussion: The rise of a new PPP model

The creation of COVAX – and the larger ACT-A structure of which it is part – shows the extent to which PPPs have become a default solution to fighting global health problems. However, COVAX and ACT-A do not simply replicate the existing PPP governance model, but also exemplify a new iteration of it: The super-PPP. The super-PPP is like established global health PPPs in many ways, which focus on a single disease, privilege technological solutions over attention to health systems and structural determinants of health, monitor themselves, and heavily advocate their own successes. At the same time, the super-PPP comes with distinct strengths and weaknesses, related to both scale and unprecedented institutional complexity.

Coordinating global health governance?

We propose that a distinctive feature of the experimental institutional super-PPP form is the ambition to unite several global health PPPs within a single institutional frame, as ACT-A and COVAX illustrate. In this respect, the super-PPP model constitutes a remarkable attempt to coordinate what has become a highly fragmented, competition-driven and frequently ineffective governance field, in which multiple PPPs develop ‘investment cases’ presented at ‘replenishment events’ to convince donors to continue their support. Gavi, the Global Fund and the like compete against each other to attract the largest possible share of donor countries’ official development assistance and philanthropic and corporate donations. Their narrow focus has created blind spots, redundancies and overlapping mandates.

There have been previous attempts to coordinate this fragmented field. For example, the International Health Partnership (IHP+), which has since developed into UHC2030, brings global health PPPs together in a multi-stakeholder discussion forum that aims to support health system strengthening (Bartsch, Citation2011; Holzscheiter et al., Citation2016). However, COVAX and ACT-A, within which it is embedded, are qualitatively different. They are not only a platform for discussion and advocacy but work towards a single operational mandate by ‘harnessing’ each constituent PPP’s distinct ‘comparative advantage’. It is thus a more tightly institutionalised attempt to coordinate what has been coined ‘market multilateralism’ (Bull & McNeill, Citation2007, Citation2019). The model draws on the democratic and procedural (input) legitimacy of the WHO, and the results and metrics oriented (output) legitimacy of existing PPPs. Their coordinating role at the highest level of governance puts the super-PPP model in direct competition with the UN and its specialised health agency the WHO, which finds itself relegated as one of many super-PPP parts and partners, and with no direct authority over them.

So far, the super-PPP model has not resolved core global health governance challenges. Established PPPs still compete against each other through investment cases, fund raising, and replenishment events. ACT-A’s different pillars received widely different degrees of support, the vaccines pillar being by far the most successful at attracting funding. In fact, as a governance approach, the super-PPP model appears chaotic, extraordinarily complex, and lacks transparency and accountability mechanisms. Whereas established PPPs are composed of mostly distinct entities like governments, philanthropic foundations, industry, NGOs and UN agencies, the super-PPP consist of other PPPs. This adds a layer of complexity (as PPPs themselves are heterogeneous), and it means that the super-PPP represents various organisations twice or even three times over. For instance, the WHO and the Gates Foundation are described as ACT-A partners but are also partners within each of the established PPPs like Gavi, CEPI, the Global Fund etc. ‘Partners’ therefore have several channels of influence – both within the super-PPP coordinating mechanism and within the boards and committees. Therefore, we say the super-PPP structure resembles a series of Russian Matryoshka dolls.

Scaling up partnerships to the global level

Another important feature that defines the super-PPP model is the vast scale of its mandate, geography, and available financing. It emerges out of an ongoing qualitative shift from traditional charity-based PPPs that aim to solve health challenges in poor countries with support from donors (e.g., Gavi) to an attempt to tackle global challenges in ways that benefit wealthy and poor countries alike. This shift is exemplified by the creation of CEPI in 2017 to tackle epidemic diseases in poor countries with the potential to spread worldwide, but the super-PPP model takes this a step further by targeting an acute global health crisis affecting rich and poor countries alike.

The effort to scale-up PPPs to the global level, however, has reinforced power-asymmetries already present in the traditional aid and charity-based model. Wealthy countries’ immediate self-interests, which are in traditional PPPs at least partly attenuated by charitable intentions, have moved centre stage, as COVAX internalised the international competition for the same scarce commodities – vaccines. To appeal to wealthy governments, COVAX did not implement the safeguards necessary to prevent self-financing countries from operating outside of it, and effectively competing with it for vaccine supplies. Despite high-level political pledges to support COVAX, these countries have adopted inward-oriented and diplomatic strategies that benefit their national interests and are at odds with COVAX’s commitment to global collaboration. Pharma partners’ profit-maximising strategies are also at odds with COVAX’s aim of globally equitable vaccine access.

In response to these challenges, COVAX has gradually lowered its ambition. From being a global procurement mechanism providing access to all countries simultaneously, COVAX has become in practice an aid-funded scheme primarily providing a limited number of vaccines to protect a small proportion of the population of its AMC-eligible countries (Usher, Citation2021). This makes it now functionally similar to Gavi’s traditional focus on subsidising childhood immunisations for countries unable to afford them.

This narrowing of COVAX’s raison d’être has been buttressed by the skewed representation of stakeholders in its governance structure. As we have shown, LICs, LMICs and civil society voices are marginal, whereas governments, organisations and individuals from the global North dominate COVAX. It is thus not surprising that COVAX has overly accommodated wealthy country and corporate interests. This issue of skewed representation reproduces shortcomings of the PPP model identified over 15 years ago that remain unresolved to date (Buse & Harmer, Citation2007; Storeng & de Bengy Puyvallée, Citation2018).

Blurring the lines between public and private interests

The super-PPP model includes private actors in its decision-making, in order to use private sector resources, assumed innovation capacity and skills. However, the institutional complexity highlighted above has contributed to a lack of clear safeguards and accountability mechanisms to secure that private interests do not take precedence over the public good.

First, as our analysis of COVAX shows, the super-PPP model relies on a form of conceptual slippage whereby any organisation that is rich or influential enough to claim a leading role in global health is considered a ‘public health organisation’ or a ‘stakeholder’ and invited to the highest echelons of decision-making. Using the term ‘global health organisations’ to describe philanthropies, PPPs and intergovernmental agencies obscures their vast differences in mandate and public accountability, and further blurs the line between public and private spheres. This conceptual slippage obscures the critical role that philanthropic partners like the Gates Foundation play in shaping and governing COVAX (The New Republic, Citation2021), beyond their self-described role as a mere ‘facilitator’ or ‘catalytic’ partner. This further challenges the remnants of democratic representation in today’s global health governance landscape.

Second, although the global pharmaceutical industry is consistently described as an essential ‘partner’, there are no clear criteria governing the behaviour of COVAX’s partners – and, as we have seen, the major vaccine producers support policies, and engage in tactics that directly work against COVAX’s access to vaccines. Finally, COVAX accomodates pharmaceutical industry requirements and has kept secret most contracts and subsidies provided to the private sector. It is unclear, for instance, how much COVAX pays for vaccine doses, or what ‘at-cost’ pricing agreed upon with several providers entails. This lack of transparency and information asymmetry about the true vaccine production costs and profit margins has been a key issue during the pandemic beyond COVAX. Inadequate performance monitoring and narrowly selected objectives make public scrutiny challenging, if not impossible.

Conclusion

Although COVAX has achieved only limited results so far, its leaders continue to brand it ‘the only solution’ to vaccine equity, setting the terms of debate and gradually reducing the notion of equity to its bare minimum, in keeping with other PPPs that have traditionally foreclosed policy alternatives (Storeng, Citation2014). But unlike other PPPs, COVAX has not solidified confidence in the partnership model, but instead created a crisis for its legitimacy. COVAX’s shortcomings, especially its lack of transparency and its incapacity to deliver on its promises, have led critics to ask whether it is ‘part of the problem’ (Devex, Citation2021), for example arguing that having suppliers on governing boards contradicts the core principle of good governance. An African Union envoy has suggested that COVAX’s failure to deliver its promised supply to the African continent is not only ‘a moral failure’, but a deliberate strategy, saying ‘those with the resources pushed their way to the front of the queue and took control of their production assets’ (The Guardian, Citation2021b). Others have argued that COVAX reproduces a ‘colonial’ mentality whereby poor countries are forced to depend on charity and leftover doses from wealthy countries (Development Today, Citation2021c).

A sign of waning trust in the PPP model is that civil society’s major response to the challenge of vaccine equity has been to work outside of COVAX, developing a global movement known as the People’s Vaccine Alliance that brings together organisations like Global Justice Now, Oxfam and UNAIDS to argue that vaccination should be a ‘global public good’. The People’s Vaccine Alliance has issued demands on Big Pharma to openly share vaccine technology and ‘know-how’. They have also called on governments to temporarily suspend patent rules at the WTO on Covid-19 vaccines, treatments, and testing during the pandemic, supporting a proposal first made by India and South Africa in October 2020. This, they claim, will ‘help break Big Pharma monopolies and increase supplies so that there are enough doses for everyone, everywhere’ (The People’s Vaccine, Citation2021).

COVAX’s staunchest supporter, the EU, has consistently opposed this move, maintaining that patents are not the major barriers to scaling up manufacturing and that removing patents will deter industry from partnering. However, over 100 countries, more than 60 former heads of state and Nobel Prize laureates, and even US President Biden now support the proposal on a temporary waiver on Covid-19 vaccines patents, providing credibility to a possible partial solution to the impasse of ‘vaccine apartheid’. The future of the public-private partnership model may be in the balance.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Aurelia India Neumark for excellent research assistance. We would also like to thank our international advisory board members and the Global Health Politics research group at the Centre for Development, University of Oslo, especially Desmond McNeill and Thomas Neumark, for thoughtful comments on a draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andonova, L. B. (2017). Governance entrepreneurs: International organizations and the rise of global public-private partnerships. Cambridge University Press.

- Bartsch, S. (2011). A critical appraisal of global health partnerships. In S. Rushton & O. D. Williams (Eds.), Partnerships and foundations in global health governance (pp. 29–52). International Political Economy Series. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Birn, A.-E. (2005). Gates’s grandest challenge: Transcending technology as public health ideology. The Lancet, 366(9484), 514–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66479-3

- Birn, A.-E. (2006). Marriage of convenience: Rockefeller International Health and Revolutionary Mexico (NED-New ed.). Boydell & Brewer. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10 .7722/j.ctt16314kz

- Bloomberg. (2021, August 10). BioNTech vaccine to give German economy extraordinary boost. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-08-10/biontech-vaccine-to-give-german-economy-extraordinary-boost

- Brown, T. M., Cueto, M., & Fee, E. (2006). The World Health Organization and the transition from ‘international’ to ‘global’ public health. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831

- Bull, B., & McNeill, D. (2007). Development issues in global governance: Public-private partnerships and market multilateralism (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Bull, B., & McNeill, D. (2019). From market multilateralism to governance by goal setting: SDGs and the changing role of partnerships in a new global order. Business and Politics, 21(4), 464–486. https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2019.9

- Buse, K., & Bertram, K. (2021, June 13). G7 Leaders made few concrete, strong, or deep health-related commitments at Carbis Bay – BMJ Opinion blog. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/06/13/g7-leaders-made-few-concrete-strong-or-deep-health-related-commitments-at-carbis-bay/

- Buse, K., & Harmer, A. (2004). Power to the partners?: The politics of public-private health partnerships. Development, 47(June), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100029

- Buse, K., & Harmer, A. M. (2007). Seven habits of highly effective global public–private health partnerships: Practice and potential. Social Science & Medicine, 64(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.001

- Covax. (2021, June 25). COVAX vaccine roll-out. https://www.gavi.org/covax-vaccine-roll-out

- Development Today. (2021a, April 14). UK buys 500,000 Pfizer vaccine doses from COVAX for domestic use. Development Today. https://development-today.com/archive/dt-2021/dt-3–2021/uk-buys-500-000-pfizer-vaccine-doses-from-covax-for-domestic-use

- Development Today. (2021b, November 11). Norway has donated almost 700,000 corona vaccine doses to poorer nations. Development Today. https://www.development-today.com/archive/dt-2021/dt-2–2021/norway-has-donated-almost-700-000-corona-vaccine-doses-to-poorer-nations

- Development Today. (2021c, July 13). Interview: Catherine Kyobutungi: Decolonise COVAX: An African critique. https://developmenttoday.com/archive/dt-2021/dt-5--2021/decolonising-covax-a-ugandan-epidemiologists-perspective

- Development Today. (2021d, March 11). Norway has donated almost 700,000 corona vaccine doses to poorer nations. Development Today. https://development-today.com/archive/dt-2021/dt-2--2021/norway-has-donated-almost-700-000-corona-vaccine-doses-to-poorer-nations

- Devex. (2021, March 11). Is COVAX part of the problem or the solution? Devex. https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/is-covax-part-of-the-problem-or-the-solution-99334

- Duke Global Health Innovation Centre. (2021). COVID-19 | Launch and scale speedometer. https://launchandscalefaster.org/covid-19

- Eccleston-Turner, M., & Upton, H. (2021). International collaboration to ensure equitable access to vaccines for COVID-19: The ACT-accelerator and the COVAX facility. The Milbank Quarterly. Retrieved June 25. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12503

- EEAS. (2020, November 13). No to vaccine nationalism, yes to vaccine multilateralism. Text. EEAS – European External Action Service – European Commission. https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/88701/no-vaccine-nationalism-yes-vaccine-multilateralism_en

- Fierce Pharma. (2021, July 30). Pfizer CEO says it’s ‘radical’ to suggest pharma should forgo profits on COVID-19 vaccine: Report | FiercePharma. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/pfizer-ceo-says-it-s-radical-to-suggest-pharma-should-forgo-profits-covid-19-vaccine-report

- Fortune. (2020, August 24). Oxford’s COVID vaccine deal with AstraZeneca raises concerns about access and pricing. https://fortune.com/2020/08/24/oxford-astrazeneca-covid-vaccine-deal-pricing-profit-concerns/

- Gavi. (2020a). Operating model. https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/operating-model

- Gavi. (2020b). COVAX welcomes appointment of civil society representatives. Retrieved October 30, from https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/covax-welcomes-appointment-civil-society-representatives

- Gavi. (2020c, July 8). Up to 100 million COVID-19 vaccine doses to be made available for low- and middle-income countries as early as 2021. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/100-million-covid-19-vaccine-doses-available-low-and-middle-income-countries-2021

- Gavi. (2020d, December 18). COVAX_Principles-COVID-19-Vaccine-Doses-COVAX.Pdf. https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/COVAX_Principles-COVID-19-Vaccine-Doses-COVAX.pdf

- Gavi. (2020e, March 9). COVAX explained. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-explained

- Gavi. (2021a). 92 Low- and middle-income economies eligible to get access to COVID-19 vaccines through Gavi COVAX AMC. Retrieved August 25, from https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/92-low-middle-income-economies-eligible-access-covid-19-vaccines-gavi-covax-amc

- Gavi. (2021b). COVAX_the-Vaccines-Pillar-of-the-Access-to-COVID-19-Tools-ACT-Accelerator.Pdf. https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/COVAX_the-Vaccines-Pillar-of-the-Access-to-COVID-19-Tools-ACT-Accelerator.pdf

- Gavi. (2021c, April 23). France makes important vaccine dose donation to COVAX. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/france-makes-important-vaccine-dose-donation-covax

- Gavi. (2021d, June 17). COVAX global supply forecast.

- Gavi. (2021e, September 1). COVAX supply forecast reveals where and when COVID-19 vaccines will be delivered. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-supply-forecast-reveals-where-when-covid-19-vaccines-will-be-delivered

- Gavi. (2021f, March 5). Gavi signs agreement with Moderna to secure doses on behalf of COVAX facility. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/gavi-signs-agreement-moderna-secure-doses-behalf-covax-facility

- Geneva Health Files, Priti. (2021, May 18). At risk: COVAX plans to vaccinate 20% of the people in LMICs. Geneva Health Files. https://genevahealthfiles.com/2021/05/18/at-risk-covax-plans-to-vaccinate-20-of-the-people-in-lmics/

- Holzscheiter, A., Thurid, B., & Laura, P. (2016). Emerging governance architectures in global health: Do metagovernance norms explain inter-organisational convergence? Politics and Governance, 4(3), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i3.566

- Medscape. (2020, August 26). They pledged to donate rights to their COVID vaccine. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/936349

- MSF. (2020, July 20). Open letter to Gavi Board Members: Inclusion of civil society in COVAX facility and COVAX AMC governance is essential. Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. https://msfaccess.org/open-letter-gavi-board-members-inclusion-civil-society-covax-facility-and-covax-amc-governance

- One.org. (2021, February 17). Vaccine Access Test. ONE. https://www.one.org/international/issues/vaccine-access-test/

- Pfizer. (2021, February 2). Pfizer full year 2020 reports. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/78003/000007800321000003/pfe-12312020xex99.htm

- Project Syndicate. (2021, May 6). Will corporate greed prolong the pandemic? | by Joseph E. Stiglitz & Lori Wallach. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/big-pharma-blocking-wto-waiver-to-produce-more-covid-vaccines-by-joseph-e-stiglitz-and-lori-wallach-2021-05

- Puyvallée, A. d. B., & Storeng, K. T. (2017, June). Protecting the vulnerable is protecting ourselves: Norway and the coalition for epidemic preparedness innovation. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Legeforening. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.17.0208

- Reuters. (2020, December 14). EU weighs donating 5% of its COVID-19 vaccines to poor nations-document. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/eu-weighs-donating-5-its-covid-19-vaccines-poor-nations-document-2020-12-14/

- Reuters. (2021a, January 22). Exclusive: Pfizer-BioNTech agree to supply WHO co-led COVID-19 vaccine scheme – Sources. Reuters. Sec. Healthcare & Pharma. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-covax-pfizer-exclu-idUSKBN29Q2R9

- Reuters. (2021b, February 26). Vaccine hoarding threatens global supply via COVAX: WHO. Reuters. Sec. Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-who-covax-idUSKBN2AQ2O5

- Reuters (2021c, June 16). Analysis: G7′s billion vaccine plan counts some past pledges, limiting impact. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/g7s-billion-vaccine-plan-counts-some-past-pledges-limiting-impact-2021-06-13/?taid=60c5e8bebd67900001a8dbf8&utm_campaign=trueanthem&utm_medium=trueanthem&utm_source=twitter

- Rushton, S., & Williams, O. (2011). Partnerships and foundations in global health governance. Springer.

- Schaik, L. v., Jørgensen, K. E., & van de Pas, R. (2020). Loyal at once? The EU’s global health awakening in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of European Integration, 42(8), 1145–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1853118

- Shiffman, J. (2017). Four challenges that global health networks face. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(4), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.14

- Stein, F. (2021). Risky business: COVAX and the financialization of global vaccine equity. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00763-8

- Storeng, K. T. (2014). The GAVI alliance and the ‘Gates Approach’ to health system strengthening. Global Public Health, 9(8), 865–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.940362

- Storeng, K. T., & de Bengy Puyvallée, A. (2018). Civil society participation in global public private partnerships for health. Health Policy and Planning, 33(August). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy070

- Storeng, K. T., & de Bengy Puyvallée, A. (2020, December 3). Why does Pfizer deny the public investment in Its Covid-19 vaccine? International Health Policies. https://www.internationalhealthpolicies.org/featured-article/why-does-pfizer-deny-the-public-investment-in-its-covid-19-vaccine/

- Storeng, K. T., de Bengy Puyvallée, A., Stein, F., & McNeill, D. (2021). What Norway should ask of the pharmaceutical industry in the Covid-19 pandemic [Policy Brief]. https://www.sum.uio.no/english/research/projects/norways-public-private-cooperation-for-pandemic-p/policy-briefs/policy-brief-panprep-sum-uio-03-2021-what-norway-should-ask-of-the-pharma.pdf

- The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. (2021, February 23). ‘Held to Ransom’: Pfizer demands governments gamble with state assets to secure vaccine deal. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2021-02-23/held-to-ransom-pfizer-demands-governments-gamble-with-state-assets-to-secure-vaccine-deal

- The Guardian. (2020, June 4). World leaders must fund a Covid-19 vaccine plan before it’s too late for millions | Gro Harlem Brundtland and Elizabeth Cousens. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/04/world-leaders-fund-covid-19-vaccine-global-vaccine-summit

- The Guardian. (2021a, January 22). South Africa paying more than double EU price for Oxford vaccine. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/22/south-africa-paying-more-than-double-eu-price-for-oxford-astrazeneca-vaccine

- The Guardian. (2021b, June 24). Rich countries ‘deliberately’ keeping Covid Vaccines from Africa, Says Envoy. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jun/24/rich-countries-deliberately-keeping-covid-vaccines-from-africa-says-envoy

- The Loop. (2021, May 25). Vaccine prices may become a political powder Keg – Felix Stein. https://theloop.ecpr.eu/vaccine-prices-may-become-a-political-powder-keg/

- The New Republic. (2021, April 12). How Bill Gates impeded global access to Covid vaccines. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/162000/bill-gates-impeded-global-access-covid-vaccines

- The New York Times. (2021, March 11). The U.S. is sitting on tens of millions of vaccine doses the world needs. The New York Times. Sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/11/us/politics/coronavirus-astrazeneca-united-states.html

- The People’s Vaccine. (2021). Join the #PeoplesVaccine global day of action. Peoples Vaccine. https://peoplesvaccine.org/take-action/

- The Washington Post. (2021, February 13). Moderna pledged to make its vaccine accessible to poor countries, but most vaccines have gone to wealthier nations. – Emily Rauhala. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/gdpr-consent/

- The White House. (2021, June 10). FACT SHEET: President Biden announces historic vaccine donation: Half a Billion Pfizer vaccines to the world’s lowest-income nations. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-announces-historic-vaccine-donation-half-a-billion-pfizer-vaccines-to-the-worlds-lowest-income-nations/

- Toronto Sun. (2021). LILLEY: Trudeau makes Canada ‘vaccine pirate,’ stealing from poor nations. Torontosun. Retrieved February 28, from https://torontosun.com/opinion/columnists/lilley-trudeau-makes-canada-vaccine-pirate-stealing-from-poor-nations

- UN. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved October 21, from https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

- UN. (2021, May 21). COVID-19: UN Chief calls for G20 Vaccine Task Force, in ‘war’ against the virus. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/05/1092442

- Usher, A. D. (2021). A beautiful idea: How COVAX has fallen short. The Lancet, 397(10292), 2322–2325. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01367-2

- Vanity Fair, C. (2021, June 4). ‘We are hoarding’: Why the U.S. still can’t donate COVID-19 vaccines to countries in need. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2021/04/why-the-us-still-cant-donate-covid-19-vaccines-to-countries-in-need

- WHO. (2009, June). Maximizing positive synergies: Interactions between global health initiatives and health systems: Evidence from countries, 250.

- WHO. (2021). The ACT Accelerator Interactive Funding Tracker. Retrieved June 25, from https://www.who.int/initiatives/act-accelerator/funding-tracker

- WHO. (2021a). COVAX. https://www.who.int/initiatives/act-accelerator/covax

- WHO. (2021b, June 26). Access to COVID-19 Tools Funding Commitment Tracker. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/access-to-covid-19-tools-tracker

- World Economic Forum. (2021, September 2). 4 Principles for urgent pharma action to combat COVID-19. Access to Medicine Foundation. https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/in-the-media/4-principles-for-urgent-pharma-action-to-combat-covid-19

- Yamey, G., Schäferhoff, M., Pate, M., Chawla, M., Ranson, K., Hatchett, R., & Wilder, R. (2020). Funding the development and manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3575660). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3575660