ABSTRACT

As advocates for social justice, our sights have been stoically fixed on fighting against and challenging what is, be it systemic inequality, structural violence and injustice. Dismantling these systems of oppression are critical, but we have lost sight of the importance of imagining what could be. That is, what a future free from that oppression might look like, might feel like, might be like. Without this ability to imagine, we are unable to create new ways of being that do not perpetuate the injustice we are trying to fight against. The bringing together of Creativity and Activism has proved vital in allowing us to begin to imagine and enact what a more equal and just world might look like. This article explores how the Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT) in South Africa has been utilising creative methodology in their advocacy to advance the rights of sex workers. SWEAT has been committed to exploring and experimenting with creative methodologies which have been incorporated into strategising, organising, mobilising and advocating for the decriminalisation of sex work. These creative methodologies have resulted in some of the biggest successes in the struggle for the human rights of sex workers in South Africa.

All organizing is science fiction. When organizers imagine a world without poverty, without war, without borders or prisons – that’s science fiction. They're moving beyond the boundaries of what is possible or realistic, into the realm of what we are told is impossible. Being able to collectively dream those new worlds means that we can begin to create those new worlds here. (Williams, Citation2015)

The human body is an unsolved mystery. Over the centuries, we have made attempts to understand her through science, religion, art, even trial and error. It is 2021 and although there is much we do understand, there is much we do not. Human beings are a complex labyrinth of neurons, feelings, muscles, bones, emotions, dreams – both the tangible and intangible, rational and irrational, that make up how we are in the world. And how we are in the world is complicated. We have the ability to think in one way and act in another. We can lie, both to ourselves and to others. We can hold two conflicting ideas at the same time. What does all this have to do with social justice activism? I would argue a lot.

As activists for social justice (which is how I identify), we are attempting to convince the world that a just world (as we define it) would be a better world for all. We believe that a fair and equal world where all creatures are treated with kindness and respect is something worth striving for. We also believe that our vision for the world, even though it does not exist yet, is something that everyone should want. But often we forget that this world is in our imagination, it does not exist yet. Importantly, our vision for the world is in constant competition with various other visions of the world.

Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have thus been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations. As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google. (Harari, Citation2011)

Before we begin our exploration into the imagined reality where sex work is decriminalised and those working in the sex industry are free from stigma and discrimination, it is important to locate myself. For the last decade, I have been an advocate for the rights of sex workers in South Africa. In 2014 I had the privilege to start working at the Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT). SWEAT is the oldest and most established sex worker rights organisation on the African continent. Founded in 1994, it has not only grown to provide legal, healthcare and psychosocial support and services to those working in the sex industry, it has been at the forefront of legislative reform, advocating for the full decriminalisation of sex work (SWEAT, Citationn.d.). It has also birthed two movements and a coalition, the African Sex Work Alliance (ASWA) and Sisonke Sex Worker Movement of South Africa, as well as the Asijiki Coalition for the Decriminalisation of Sex Work in South Africa.

In South Africa, there are an estimated 153,000 sex workers (SANAC, Citation2013). Given the criminalised and stigmatised nature of sex work, this is not an entirely accurate number. Legally, South Africa currently follows the model of full criminalisation of sex work. Sex work and related activities (brothel-keeping, solicitation, etc.) are specifically criminalised by the Sexual Offences Act 23 of 1957, the Sexual Offences Amendment Act of 2007 and municipal by-laws, which all play a role in the legal control and regulation of sex work. Simply put, it is a crime to sell sex, buy sex and live of the proceeds of sex work in South Africa. The laws, as they stand, are very difficult to prosecute and as a result, sex workers are seldom prosecuted under the criminal law but are more likely to be arrested, harassed, abused and released. In a study conducted by the Women’s Legal Centre, 70 percent of sex workers interviewed experienced some form of abuse at the hands of police (WLC, Citation2012). The most common human rights violations perpetrated by law enforcement against sex workers were assault and harassment, arbitrary arrest, violations of procedures and standing orders, inhumane conditions of detention, unlawful profiling, exploitation and bribery, and denial of access to justice. Unsurprisingly, most sex workers are reluctant to approach the police to report crimes committed against themselves or others. In addition, as violence and harassment perpetrated against sex workers occurs with impunity, sex workers are seen as easy targets to perpetrators.

Moreover, with sex work not being recognised as legitimate, legally protected work, sex workers’ access to services such as healthcare and justice are hindered. The HIV prevalence amongst sex workers in South Africa is approximately 59,6% with roughly 5% of sex workers being reached with comprehensive HIV services (SANAC, Citation2016). However, studies also show that most sex workers know their HIV status as well as try to practice safe sex behaviours. The criminalisation of sex work drastically impedes successful HIV and other public health interventions because it continues to fuel stigma against sex workers and dissuades sex workers from accessing healthcare services. Police also go as far as to confiscate condoms from sex workers as ‘evidence’ of sex work. The illegal status of sex work has created conditions in which exploitation and abuse can thrive.

What is the solution to this heinous reality? Sadly, there is no one solution as sex workers are victims to multiple, overlapping layers of stigma and discrimination. They are subject to violence and harassment not only for the stigmatised work that they do but also because, the majority of sex workers in South Africa are women, people of colour, and poor. These intersecting identities each come with their own sets of prejudices. Although combatting this depth and breadth of systemic injustice seems insurmountable, evidence shows that legislative reform, specifically the full decriminalisation of sex work would be an essential start (NSWP, Citation2010).

There is extensive research from the World Health Organization (Citation2014) and UNAIDS (Citation2014) showing that decriminalisation will lead to better health outcomes for sex workers and that sex workers will be more likely to report cases of abuse and other human rights violations (Mossman & Mayhew, Citation2007, pp. 10–11). In addition, the legal recognition of sex workers and their occupation maximises their protection, dignity, and improves their working conditions (Mossman & Mayhew, Citation2007) and serves to recognise the rights of all people to freedom, privacy and bodily autonomy (SWEAT, Citation2019). Do not take my word for it, these bodies are just a few that support the full decriminalisation of sex work: Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the World Health Organisation, the Global Network of Sex Worker Projects, not to mention South African bodies such as the South African National Aids Council, the Commission for Gender Equality, and over 70 civil society organisations that are members of the Asijiki Coalition for the Decriminalisation of Sex Work in South Africa.

A fair question to ask is, if all the evidence points to legal reform to decriminalise sex work, why hasn’t every country done it yet (other than New Zealand)? There are many reasons, but one very important reason is that we assume that policymakers make evidence-based decisions. They do not and the same can be said for non-policy makers. In my experience, policymakers have multiple (often competing) motivations vying for their attention. All these factors come together in a complicated constellation that then frames how they think, act and make decisions. As activists, we often forget about the whole constellation and narrowly focus on the dictum ‘the truth will set us free’. We assume that if people in power have the right information, if they read our fact sheet or our research report, that they would make the right decision. This has proven time and time again to be untrue. I often encounter earnest individuals working for various causes handing out flyers, only to find the rubbish bin around the corner overflowing with them. As activists we have to do better, we have to help the truth along so that it can be heard and, more importantly, acted upon. And this is where the power of imagination and creativity comes in.

In 2015 I learnt a powerful concept: ‘Effect, Affect and Æffect’. At a workshop held by the Centre for Artistic Activism (CAA) we explored how:

To have an effect is to cause a demonstrable, often physical and material, change. To generate affect is to stimulate feelings or create an emotional state in a person or group of people. When we think of activism we often think in terms of its effect. Activism, as the name implies, is the activity of challenging and changing power relations, to act and generate an effect. Affect, however, is a term we usually use when speaking of the arts. Art tends not to have such an instrumental use. It is hard to say what art is for or against; its value often lies in showing us new perspectives and new ways to see our world. Its impact is often subtle and hard to measure, it generates an affect. (The Centre for Artistic Activism, Citation2018)

At SWEAT, we took this concept to heart. We wanted to change the law, but in order to do that, we had to move lawmakers (and the general public) to empathise with our struggle, inspire them to act and have them buy into our imagined world of decriminalisation. These are some of our experiments with creative activism, the lessons we learnt, and what they achieved.

We are all creative

‘I’m not creative, I can’t even draw’, this is something I hear often. The realm of creativity only belongs to artists and is not a space for activists and definitely not for sex workers. As activists for the rights of sex workers, we decided that this space was also for us. But we needed help to express ourselves in ways other than protest and policies. We combined our world of activism with art in a few experiments.

‘I am what I am: places, faces and spaces’ Exhibition at Iziko Slave Lodge

This was a multidisciplinary collection of photography, video and writings by the Sex Worker Feminist Collective at SWEAT (Mbasalaki & Matchett, Citation2020). Over three years we collaborated with various artists to create an exhibition where all the content was produced and curated by sex workers. These artists worked with us to develop technical skills such as photography and creative writing. However, more importantly, through these collaborations over time we were empowered to own our creative process becoming increasingly confident as our skills and understanding developed. This 3-room exhibition was exhibited in a National Gallery, the Iziko Slave Lodge in Cape Town. The exhibition was not overtly about decriminalisation, law reform or policy change, rather it was a reclamation of stories and space. Too often, people who sell sex have their stories told through the lenses, voices and perspectives of others. This exhibition was a bold challenge to put the stories back in the hands of those who have lived it, as well as occupy space that is usually denied to them ().

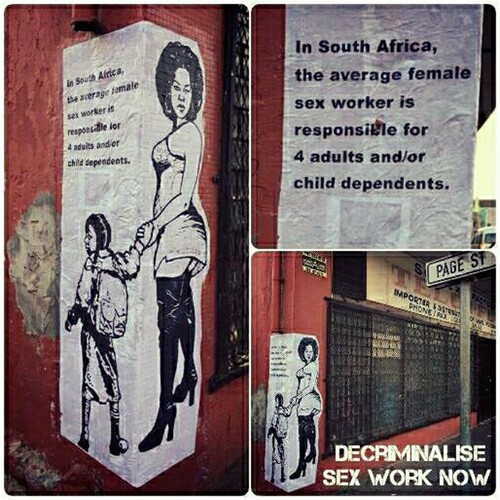

‘Street Corner Mums’

We also experimented in the realm of street art. Inspired by a campaign by the Argentine Prostitutes’ Association (Radu, Citation2013), we created our own ‘Street Corner Mums’ Campaign for Mother’s Day. We wheat pasted life-size art works that wrapped around street corners showing stereotypical sex workers on one side, but when you turn the corner, you see that she is caring for a child accompanied by the statistic that in South Africa the average female sex worker is responsible for 4 adults and/or child dependents (Richter et al., Citation2013). These artworks proved very effective in catching people off guard and making them question the assumptions and stereotypes that they have about sex workers ().

Sex Worker Theatre

SWEAT has a long history of using performance as part of our activism toolbox with an established theatre group Umzekelo who often performed at conferences or for significant human rights days, however, the establishing of a Sex Worker Theatre was entirely new terrain. A partnership with the University of Cape Town Drama Department and the African Gender Institute, resulted in a theatre group where sex workers, with technical support, crafted plays and physical theatre pieces that are performed to paid audiences in Cape Town. The stories told are not necessarily about activism, but about the complex lives and experiences of sex workers ().

Live performance as activism does not necessarily evoke the kind of mass rally activism that registers when one thinks of protest action globally, but rather incites conversations, discussions, dialogues and debates that stimulate people to consider their roles in the situation and how they are able to actuate it from a point of personal observation to personal action. (Mbasalaki & Matchett, Citation2020)

Audiences have left these performances and exhibitions not necessarily knowing the intricacies of the law as it relates to sex work, but rather with insights and alternative narratives about the lives of people who sell sex that do not conform to the Hollywood and moralist stereotypes. Through art we were able to affect the audience.

Dream big

As activists, we often limit ourselves to the realm of the ‘realistic’ and the ‘achievable’ and rarely venture into the ‘truly optimistic’ or the ‘impossible’. This is a mistake. We need to dream big, to imagine the impossible, to push past our comfort zones as we are trying to build another world. In the words of Arundathi Roy (Citation2005) ‘Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing’. If we cannot bring ourselves to imagine the world we want to live in, how are we going to get others to want to live in it with us?

This is a lesson we learned in preparation for the 2016 International Aids Conference (IAC). In a brainstorming session with the CAA, we were listing what we wanted to achieve at the IAC, which was the usual: ensure that sex workers voices are heard, lobby particular policymakers, network with international sex worker organisations, etc. When asked to dream of an impossible goal, someone said ‘Meet Elton John! Because I love his music’. Although that was a fine reason to try and meet Sir Elton John, another more relevant reason was that the Elton John Foundation is a vocal advocate for the decriminalisation of sex work, funds sex worker rights causes in Europe and was about to start funding in Africa. We decided to take this goal seriously to stretch our imaginations and set our bar higher. What ensued was a barrage of ideas ranging from online pestering, to stalking, to sneaking into his hotel room dressed as hotel staff. We were trying to do what we thought was impossible, meeting an icon like Sir Elton John. But after asking ourselves, ‘how do you get an audience with someone whose personal assistant probably has a personal assistant?’, we settled on giving them an award, surely then they have to show up? The Asijiki Award for Courage and Initiative was born. Sir Elton could not say no to being the first-ever recipient of the inaugural Asijiki Award, hand-chosen by the sex worker movement of South Africa. And so we met him, in the lobby of his hotel, where he graciously accepted our beautifully crafted award and had a dance with us. A few months later, we secured a meeting with the Foundation about the possibility of applying for funding, something that would have never happened had we used our usual toolbox of polite introductory emails. For us, this was the ultimate lesson to dream big as our once impossible objective, with a little creativity, became possible ().

Be seriously funny

The work that human rights activists do is universally acknowledged as very serious work. The issues are serious, the impacts are serious, we are doing the serious work of fighting for fundamental human rights. One might say this is no laughing matter, however, I would disagree. I would argue that we can and should be seriously funny. Not by making light of the issue, but by using levity and humour to surface the ridiculousness of the fight for basic rights (New Tactics in Human Rights, Citation2013). Humour is also used to challenge peoples’ beliefs and prejudices in a way that feels less accusatory. At the end of the day, we are trying to move people to care about our issue, and it is far easier to move people when we call them in as opposed to calling them out (Branagan, Citation2007). We experimented with humour and playfulness in a number of interventions, one being, what we came to call ‘The Desk of Disappointment’.

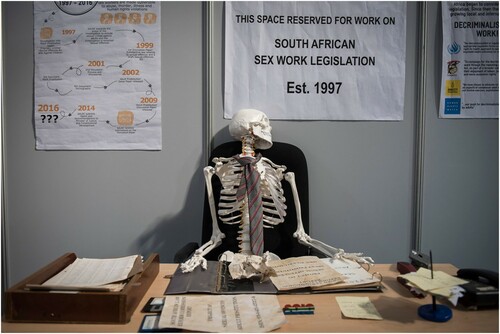

South Africa had initiated processes to investigate law reform around sex work in 1997. In 2016, progress had completely stalled with the Department of Justice failing to release a report conducted by the South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC). Aware that no progress could be made without the release of this report, we had attempted countless interventions to get this report released. We had tried protests, letters, lobbying, media campaigns, but nothing had worked. Then, together with the CAA, we created an installation to illustrate in a non-technical, obvious and humorous way, how ludicrous it was that we had been waiting 19 years for movement in this matter. The Desk of Disappointment was unveiled at the IAC. It consisted of a life size office desk with 1990s office paraphernalia such as a stiffy disk marked ‘Project 107’ (the name given to the process), tea-stained to-do lists and old versions of the report, and to top it off, a life-size skeleton in a tie, covered in cobwebs sitting at the Desk. The sign above read ‘This space is reserved for work on South African sex work legislation. Established 1997’. This installation was a wild success. Not only did it provide great fodder for the media, but in one look, people understood exactly what we were unhappy about and what we wanted. More than that, they could feel our frustration and see how reasonable our demands were. We even set up the installation outside an event where the Deputy Minister of Justice was speaking. Needless to say, he was not impressed. The report was released within a year ().

Figure 5. ‘The Desk of Disappointment’ at the 2016 International Aids Conference. Photo Credit SWEAT.

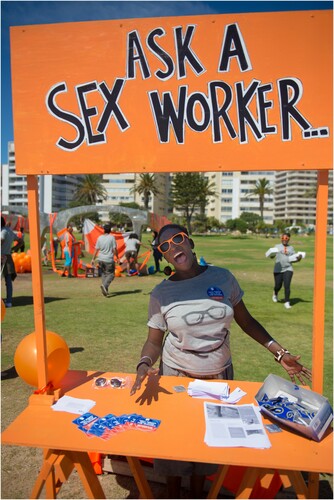

This sense of fun was also echoed in our approach to community engagement. As NGO’s we tend to follow a recipe for community engagement: a branded gazebo and fold-out trestle table, a pull-up banner, stacks of fact sheets, booklets and stickers and a couple of earnest, well-intentioned people trying to engage the public. We traded that in for a bright orange lemonade stand with ‘Ask A Sex Worker’ emblazoned on it. We played music, danced and offered a range of orange prizes, like sunglasses, to anyone who engaged with us. We have also, on occasion, offered free hand massages – because once they have said yes, they are a captive audience, and you can tell them all the reasons why we need to decriminalise sex work. This approach dramatically altered how people engage with SWEAT. It was so popular that we were invited to Parliament to set up the booth during the Annual Budget Speech. The booth also created a layer of protection from law enforcement (which is essential as sex work is illegal) because when police see the festivity associated with the booth, they do not perceive us as activists or ‘trouble-makers’ therefore, they are unlikely to harass us (or ask if we have permission, which we never have) ().

Show people the future

Previously I referred to a quote where organising is described as science fiction, that as activists we are trying to create a world that does not exist yet. Creativity is fundamental in supporting social justice activists to achieve our dreams because creativity can help us paint that world. It is very difficult to try and convince people to buy into your vision of the world if you cannot show it to them. Creative activism helps us bring these worlds to life, where people can feel what living in this world would be like, sound like, taste like and smell like.

One of our biggest experiments in creating the future we want to see, happened in 2019, the year of South Africa’s General Election. Most social justice organisations were waiting for the dust to settle after the election before embarking on any major campaigns. However, we thought this would be a missed opportunity. We began to daydream about what it would be like to have a sex worker as a president. Who would she be? What would she stand for? Who would be in her Cabinet? We even looked into what it would take to actually form a political party, but that was far too daunting. But then we thought, what if people believed it to be a real political party? The Sex Worker Action Group (SWAG) was formed. A faux political party with a very real candidate, platform, campaign video, slogan (‘Your freedom. Your SWAG’), merchandise and posters. The public believed it! The Campaign sparked conversations about sex work, and we were invited to speak on a number of high-level platforms. What surprised us most was ultimately how well the Campaign was received. Although there was the expected backlash and trolling on our social media, the majority of engagements were positive. This opened our eyes to the fact that there was an appetite for political change in South Africa. Not only did we shift the narrative about sex workers, but both of the leading opposition parties included the human rights of sex workers in their election manifestos (Democratic Alliance Election Manifesto, Citation2019; Economic Freedom Fighters Election Manifesto, Citation2019), something that had never been done before ().

Conclusion

In the serious world of human rights, it is often asked, how can imagination and play help in the face of such violence, exploitation and despair? In my experience, creative activism has provided myself and the sex worker rights sector many valuable offerings. It has given us sorely needed renewed energy. Planning and executing these interventions were exhausting, but they were also fun, bringing us together to use our bodies and minds in creative ways, something we do not often get to do in courts, offices and conference rooms. This approach has also won us more allies and increased our visibility by making our issues clear and accessible to members of the public, as well as the media. During the period of these interventions SWEAT launched the Asijiki Coalition for the Decriminalisation of Sex Work that has grown to over 70 organisational members. There were also major shifts in policies with the decriminalisation of sex work being acknowledged in the National Strategic Plan on Gender Based Violence and Femicide (Citation2020), the SANAC National Sex Worker HIV Plan (SANAC, Citation2016) as well as being supported by the two biggest trade unions in South Africa COSATU and FEDUSA.

These major strides forward were a result of the 20 years of sustained advocacy pressure, public education and sex worker mobilisation and empowerment at the core of SWEAT’s work. But they were also due to the courageous experimentation with tools that are not ordinarily in the human rights activism toolbox. The combined internal support from SWEAT leadership to push boundaries and comfort zones and the external support from visionary organisations like the CAA enabled the sex worker rights movement to reclaim our narrative, tear down stereotypes and assumptions, and occupy our seat at the table. We still have a long way to go in terms of ensuring sex work is decriminalised and that sex workers are able to access their basic human rights; however, the introduction of creative activism into our fight has made us believe that another world is indeed possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Branagan, M. (2007). The last laugh: Humour in community activism. Community Development Journal, 42(4), 470–481. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44259076?seq=1. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsm037

- Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, No. 32 of 2007, s. 11.

- Democratic Alliance. (2019). Election manifesto. https://cdn.da.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/22160849/A4-Manifesto-Booklet-Digital.pdf.

- Economic Freedom Fighters. (2019). Election manifesto. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019-EFF-MANIFESTO-FINAL.pdf.

- Harari, Y. (2011). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Random House. Kindle Edition.

- Mbasalaki, P., & Matchett, S. (2020). Aesthetic grammars of social justice: Sex work reimagined. Studies on Home and Communities Science, 14(1-2), 7–18. doi:10.31901/24566780.2020/14.1-2.344. http://krepublishers.com/02-Journals/S-HCS/HCS-14-0-000-20-Web/HCS-14-1-2-000-20-Abst-PDF/S-HCS-14-1-2-007-20-344-Mbasalaki-P/S-HCS-14-1-2-007-20-344-Mbasalaki-P-Tx[2.pdf].

- Mossman, E., & Mayhew, P. (2007). Key informant interviews: Review of the prostitution reform act 2003. Crime and Justice Research Centre. Victoria University of Wellington. https://www.nzpc.org.nz/pdfs/Mossman-and-Mayhew,-(2007a),-Key-informant-interviews.pdf.

- Network of Sex Worker Projects. (2010). Sex work and the law: The case for decriminalisation. https://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/Sex%20Work%20%26%20the%20Law.pdf.

- New Tactics in Human Rights. (2013). Using Humor to Expose the Ridiculous. https://www.newtactics.org/conversation/using-humor-expose-ridiculous

- Radu, R. (2013, June 17). Argentina's prostitutes – mothers first, sex workers second. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/17/argentina-prostitutes-advertising-campaign.

- Richter, M. L., Chersich, M., Temmerman, M., & Luchters, S. (2013). Characteristics, sexual behaviour and risk factors of female, male and transgender sex workers in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 103(4), 246–251. http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/6170. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6170

- Roy, A. (2005). An ordinary person's guide to Empire. South End Press.

- Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Taskforce. (2019). Why should sex work be decriminalised. http://www.sweat.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Why-Sex-Work-Should-be-Decriminalsed.pdf.

- South African Department of Justice. (2020). National strategic plan on gender based violence and femicide. https://www.justice.gov.za/vg/gbv/NSP-GBVF-FINAL-DOC-04-05.pdf.

- South African National AIDS Council. (2013). Estimating the number of sex workers in SA, 2013. http://www.sweat.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Sex-WorkersSize-Estimation-Study-2013.pdf.

- South African National AIDS Council. (2016). South African National Sex Worker HIV Plan, 2016-2019. https://southafrica.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pubpdf/South%20African%20National%20Sex%20Worker%20HIV%20Plan%202016%20-%202019%20FINAL%20Launch%20Copy...%20%282%29%20%281%29.pdf (accessed March, 2021), p. 13.

- SWEAT. (n.d.). http://www.sweat.org.za/.

- The Centre for Artistic Activism. (2018). Accessing the impact of artistic activism. https://c4aa.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Assessing-the-Impact-of-Artistic-Activism.pdf.

- UNAIDS. (2014). The gap report 2014: Sex workers. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/06_Sexworkers.pdf.

- Williams, K. (2015, April 13). Demanding the Impossible: Walidah Imarisha Talks About Science Fiction and Social Change. bitchmedia. https://www.bitchmedia.org/post/demanding-the-impossible-walidah-imarisha-talks-about-science-fiction-and-social-change?fbclid=IwAR0r9mbjnJKq1tr7jb6qDUsASRwyat4BBsfrnhUIMmCzOKaOr9c7uD4JBIg.

- Women’s Legal Centre. (2012). Stop harassing us! Tackle real crime: A report on human rights violations by police against sex workers in South Africa. http://wlce.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/210812-FINAL-WEB-version.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2014). Sex workers. http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/sex_work/en/.