ABSTRACT

In this essay, we explore how Instagram-based account ‘Assault Police’ uses the tools of social media to name and shame (alleged) perpetrators and to give testimonies of sexually intimidating, violent experiences. We propose the concept of 'framing' to study the development of the account and the campaign, which allowed to create a very local, Egyptian #MeToo movement. By analysing photos posted by the account between July 2020 and January 2021, our findings indicate the ability of Assault Police to adapt to different challenges. Moreover, the account which started as a single-issue movement soon developed into an initiative which focuses on structural roots of violence against women.

Introduction

On 1 July 2020, a seemingly ordinary Instagram account named ‘reportabz’ was created. It featured a photo of a young man (initials A.B.Z.) and accused him of being a sexual predator. The account ‘reportabz’ was later renamed ‘Assault Police’ and has been active to this day.Footnote1 The activity of Assault Police on Instagram, aimed at combatting sexual violence, is the focus in this essay. We analysed the posts of Assault Police and we will show how Assault Police has been operating and was able to generate that much attention.

The majority of women in Egypt are victims of behaviours that lie on a continuum of sexual violence (Kelly, Citation1988). Sexual violence is defined as

any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work. (Krug et al., Citation2002, p. 149)

Assault Police is an Instagram account which documents and highlights sexual violence against women. The account provides a space for victims to tell their stories while also charring out advocacy work aiming to change laws in Egypt. Assault Police belongs to a broader tradition of digital feminism. As Loney-Howes et al. (Citation2021) assert, feminists used online spaces to raise awareness around sexual violence and rape culture since the early 2000s. Many movements and initiatives were created to address everyday sexual violence on the streets such as ‘Hollaback’ (2005) in the US and Harrassmap (2010) in Egypt (Loney-Howes et al., Citation2021, p. 5).

Arguably, the most important movement online to expose sexual violence against women was #MeToo. It was sparked by actress Alyssa Milano in November 2017 asking victims of sexual violence to share their stories (Fahmy & Ibrahim, Citation2021). #Me Too was considered to be the largest movement on social media in 2017 and inspired different spin-offs such as QuellaVoltaChe, in Italy and Ana Kaman in the Arab world (Fahmy & Ibrahim, Citation2021). Moreover, on Instagram, there was also a similar initiative from the Netherlands called #dearcatcaller by Noa Jansma, a student in the Netherlands. She decided to post selfies for a month with her standing in front of the harassers (catcallers) (Jansma, Citationn.d.). Assault police then, comes as a natural extension to all these initiatives and as a new attempt by feminist activists to shed light on sexual violence and provide a space for victims to tell their own stories. In this essay, we explore how Assault Police has employed Instagram to name and shame (alleged) perpetrators and to give testimonies of sexually intimidating, violent experiences. The essay first describes the anti-sexual harassment movements in the 2000s and their research on the magnitude of the problem. After that, we will describe the analytical perspective of framing developed within the context of social movements. Next, the legal and policy framework and changes thereof are discussed. After we explain the method and data, it becomes clear how Assault Police has been operating and was able to generate much attention.

Social and legal context

Historically, Egyptian women have been suffering from sexual harassment from the beginning of the existence of the Egyptian modern state. More recently, acccording to a UN Women study around 99.3% of a sample of 2332 women across Egypt have been victims of harassment, including touching and verbal sexual harassment (El Deeb, Citation2013). Similarly, a study focusing on greater Cairo (Cairo, Giza, Kalyouba) by Harrasmap concluded that in a sample of 300 women, 95% got harassed (Fahmy et al., Citation2014).

As Hammad (Citation2017) asserts, news articles regarding sexual harassment go back all the way to 1892. However, she also noticed that sexual harassment reports were framed as a public morality issue and reflected an ‘anxiety’ of women’s presence in the public sphere and urban spaces (Hammad, Citation2017, p. 46). Interestingly enough, 100 years later, blaming the victim and problematising women’s presence in public sphere is still one of the tactics employed by the government in Egypt.

Despite the magnitude of the problem, it had been neglected for a long time since it was considered to be shameful to be a victim of sexual harassment (Nordenson, Citation2017). This shame results from a society and official media who blame a victim for the choice of clothes and her behaviour in public settings (FIDH et al., Citation2014). Thus, cyberspace was an obvious space for bloggers and activists to counter the arguments repeated by official media regarding sexual harassment. Indeed, using the Internet to address sexual harassment started back in 2006 (Mohamed, Citation2012).

After the 2011 revolution against President Mubarak many initiatives like ‘I saw Harassment’ (2012) or ‘Anti-Harassment Movement’ (2012) sprung up. We focus on the account of Assault Police and we will show how it developed in a short time to be one of the main actors in combating sexual violence against women in Egypt.

Anti-sexual harassment movement in the 2000s

Assault Police is not the first attempt to address or fight sexual harassment in Egypt (Hunt, Citation2020). Many initiatives have been created over 2000s, in particular at the time of the 2011 revolution which ended the 30-year rule of Mubarak. Here, we introduce the most prominent examples.

First, the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights (ECWR) was the first civil society’s response against sexual harassment in late 2005. In her study on activism against sexual harassment, Abdelmonem (Citation2016) reports that the ECWR started an informal programme to fight sexual harassment. The ECWR commissioned a survey of 1010 female Egyptian women, indicating that 83% had experienced sexual harassment. Sexual harassment included for example touching, noises (e.g. whistling, hissing noises, kissing sounds), ogling of women's bodies, verbal harassment of a sexually explicit nature, stalking or following, phone harassment and indecent exposure (Hassan et al., Citation2008). During that time, ECWR was working in an authoritarian context which can make claims-making process risky. The Mubarak regime used co-optation and repression to control civil society in Egypt for decades (Herrold, Citation2016). What made ECWR and other organisations working to combat sexual harassment so contentious, was that sexual harassment has also been a tool used willingly by the government itself. The Mubarak regime disrupted protests by using sexual harassment. For example, in 2005 the government-sponsored men to attack female protesters, stripping them naked on the streets (BBC, Citation2005; Rizzo et al., Citation2012). As Amar (Citation2011) notices, the state used sexual violence as the main approach towards women protestors. This led to the normalisation of sexual harassment, since the state was the main organiser of gender relations within a society (Connell, Citation1990; Heijthuyzen, Citation2018).

Rizzo et al. (Citation2012) concluded that despite this authoritarian context, ECWR managed to shed light on sexual harassment in Egypt by using local network and international ties.

In her study of anti-sexual harassment initiatives in North Africa, Skalli (Citation2014) describes how these new initiatives used mixed tools between online and offline activism, and in general represented a generational shift in fighting sexual harassment. She explains that between 2005 and 2010, many feminist initiatives involved collaboration between men and women. She gives the example of ‘Nazra for feminist study’, an NGO that is one of the biggest women rights groups in Egypt (Skalli, Citation2014, p. 250).

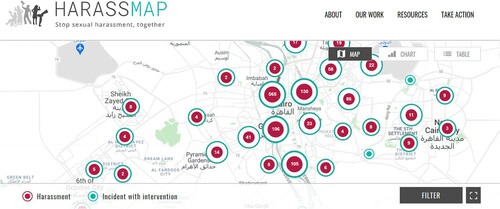

Year 2010 witnessed the emergence of an important actor fighting sexual harassment. Harassmap was founded in December 2010. Harassmap aims to ‘engage all of Egyptian society to create an environment that does not tolerate sexual harassment’ (Harassmap.org, Citationn.d., see ). In their study of action-oriented response to sexual harassment in Egypt, Abdelmonem and Galán (Citation2017) found that Harassmap encouraged the bystanders to take an active role to fight sexual harassments. The study highlights how Harassmap employed different tools in its campaigning using Facebook posts and visual aids. For example, a cartoon is posted on their Facebook page with the caption ‘why act stupid’. The cartoon depicts a woman being harassed in the metro while everyone ignores it (Abdelmonem & Galán, Citation2017). In her study of Harassmap, Abdelmonem (Citation2020) describes the unique approach the initiative takes in its media campaigns citing the example of ‘The harasser is a criminal’ campaign in 2015. The campaign entailed using fear from punishment to deter the harasser while at the same time urging the bystanders to intervene to end sexual harassment in Egypt. This approach of bystander involvement is one of the main characteristics of Harassmap, which Assault Police will also employ later.

Figure 1. Screenshot of HarassMap (harassmap.org/en/), presenting stories of sexual harassment in Cairo.

During the revolution and despite the absence of reports of sexual harassment during the 18 days of protest at Tahrir, at the time of the celebrations for Mubarak’s ousting, the CBS correspondent Lara Logan became a victim of a brutal mass sexual assault (Langohr, Citation2013). Afterwards, Tahrir Square witnessed multiple sexual assaults on different occasions and even a march against sexual harassment on 8 June 2012 was attacked by harassers (Langohr, Citation2013). As FIDH et al. (Citation2014, p. 12) puts it ‘The attack on women is calculated and organised so as to scare women away from the public sphere, to punish women for their participation and to keep them at home’. What is notable, is that the state did nothing to stop this violence. In fact, between November 2011 and July 2013, there was no police personnel or forces in Tahrir Square, which led to a high increase in sexual violence (FIDH et al., Citation2014, p. 11). Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment (OpAntiSH) states that during their work on Tahrir Square between 28 June and 7 July 2013, 186 case of sexual assault were documented, varying between-group sexual harassment to a violent rape (Kirollos, Citation2013). Thus, many citizen-based initiatives were undertaken to fight sexual violence in Tahrir and to fill the void of state inactivity.

OpAntiSH is one of the two initiatives that Langohr (Citation2013) examined in her study of combating sexual assaults at Egyptian protests. She noticed how the sexual harassments at Tahrir led to the birth of different types of initiatives. In addition to OpAntiSH, she focused on Tahrir Bodyguards. The two groups worked on the ground with intervention teams to rescue victims. This represented a new type of activism towards sexual harassments. Langohr (Citation2013) highlights the differences between the groups regarding their foundations. While OpAntiSH activists knew each given that they originating from human rights activist groups, Tahrir Bodyguards were strangers who had in common that they all responded to the call of the group founder on Twitter (Langohr, Citation2013). Moreover, when it came to participation by women, OpAntiSH since the beginning included women in their intervention teams. While reluctant at the beginning, Tahrir Bodyguards were forced to include women onboard, as victims felt safer with them (Langohr, Citation2013).

The anti-sexual harassment initiatives adapted to changing times and circumstances as well. The government as well stepped up its efforts. Tadros (Citation2015) examined the changes that occurred to Harassmap and ‘Imprint’ (in Arabic ‘Basma’). Basma was another intervention group active in Tahrir. Tadros (Citation2015) concludes that Basma had to change their vigilante identity and work with the police, and to dismantle their patrol groups and direct their efforts to other sexual harassment combating activities. Harassmap cooperated with the government of Alexandria to start outreach activities in June 2015 (Tadros, Citation2015). This is related to changes in the legal and policy framework, which we will describe below.

Legal and policy framework

Until 2014 the Egyptian law did not recognise sexual harassment as a specific crime, instead article 306A stated

any assault on a female in a way which hurts her bashfulness by words or actions in a public space or a frequented space is punishable by an imprisonment for no longer than a year and a fine between 200-1000 pounds’ (306A, penal code). The law also included wired communication in the possible spaces of assault (306A, penal code). However, the law did not cover mass harassments and did not give a definition of sexual harassment.

Article 306A any behaviour that involves assaulting others in a public or private or a frequented space by acts or innuendoes or suggestions of sexual or immoral nature, either by signal, verbal, or action by any means including wired and wireless communication is punishable by imprisonment for no less than 6 months, either/or a fine between 3000-5000.

Article 306B any acts mentioned in article 306A is considered sexual harassment if the aim of the perpetrator was sexual benefit, which for it he will face imprisonment for no less than a year either/ or a fine between 10000-20000 Egyptian pound. [translations by the first author]

Social movements and framing

We based our analytical perspective on the concept of framing developed within the context of social movements. For Goffman ‘frame’ represents a ‘schema of interpretation’ which allows individuals to be able to identify, understand and locate events in their life and in the world around them (Goffman, Citation1974, p. 21).

The framing process is the result of actors in social movements actively constructing a meaning concerning events in their environment (Vijay & Kulkarni, Citation2012). Benford and Snow (Citation2000, p. 614) presented the concept of collective action frames which are ‘action-oriented sets of beliefs and meanings that inspire and legitimate the activities and campaigns of a social movements’. In the framing process, the activists in a social movement work as signifying agents who produce and maintain ‘the constructed meaning’ in front of supporters, enemies, bystanders, observers (Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Snow & Benford, Citation1988).

In other words, framing is about creating a common meaning of a certain event which can rally supporters, challenge opponents and overall define what the issue is. It is both a process of simplifying events and signifying their meaning. At the same time, it involves presenting the world as the movements see it. Snow (Citation2013) argues framing has three functions. It focuses the attention on meaning or an issue, it articulates and connects different elements of the issue so that a certain meaning will be constructed, and it can play a transformative role since it can challenge or change a certain understanding of an issue or a certain meaning and how it relates to the actors involved. Benford and Snow (Citation2000) present three types of framing processes: diagnostic framing, prognostic framing and motivational framing.

Diagnostic framing entails identifying the problem and who to blame. Prognostic framing does not aim to merely provide the solution but also to provide struggles and tactics and long and short-term targets. The motivational framing goes beyond the diagnostic and prognostic by calling for action and by involving mobilisation. We will see that Assault Police actively calls for action and mobilises people. Snow (Citation2013) argues that motivational framing requires ‘constructing “vocabularies of motive” that provide prods to action by, among other things, overcoming both the fear of risks often associated with collective action and the so-called “free rider” problem’.

Method: Data and analysis

The first author created a new Instagram account and made screenshots of all 81 posts by Assault Police that were published during the period 1/7/2020–17/1/2021. The posts contain 128 images and text in Arabic and/or English. We used qualitative content analysis to study the evolution of Assault Police. First, we looked at posts in their chronological order and coded the topics of the posts (e.g. ABZ-case, victim testimony, social media accounts urging men to film when they sexual harass women). The first author used information from (Arabic) news media to make sure we understood what was going on and where the posts referred to. This information informed and contextualised the analyses. The visual practices of the posts were analysed as well, for example the use of colour, typography and images such as photographs, drawings and emojis.

We analysed, discussed and reflected on the posts, the events occurring, and the visuals used in the posts to come to an understanding of the evolvement of Assault Police and the framing processes. We created a timeline in which we embedded the different posts by Assault Police and events in a chronological order. The process of coding and analysing was a qualitative, iterative process that led to the results described next.

Results: Instagram based framing in action – a case study of Assault Police

First, we will describe how posts on the Instagram account of Assault Police evolved over time. Next, we discuss how the posts of Assault Police show diagnostic, prognostic and motivational framing. Within a space of just over 6 months Assault Police transitioned from a one-person one-issue based initiative to a movement with a risk-taking inspirational front-runner addressing a variety of issues relating to various forms of sexual violence. A year later the account had 106 posts and 346,000 followers (@assaultpolice, Citation2021).

Different themes emerged during the development of Assault Police, beginning with the first post on the ABZ-case on the first of July 2020. During our analyses we noticed themes such as outreach and raising awareness, victim testimonies and victim aid. These themes were adopted by the account without forgetting the main mission which is to expose sexual abusers. Thus, we see the account focusing on a specific case when someone provides details of sexual abuse. An example is the case of the #Fairmont incident (an alleged mass rape that took place in Fairmont hotel in Cairo) and a psychiatrist accused of serial rape (post 9 January 2021).

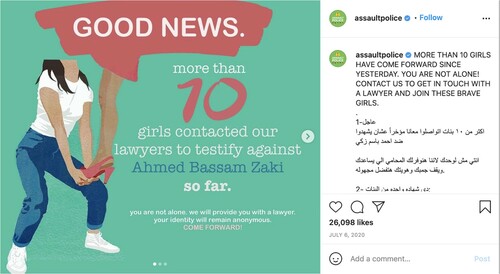

The analysis of the posts shows how Assault Police started with a single case that was clear in the first name of the account ‘reportabz’ which aimed to highlight the accusations against ABZ, a former American University of Cairo (AUC) student. The first post of 1 July 2020 presented a timeline of ‘ABZ’’s studies tracking him and his alleged abuses. By 2 July 2020 and after 24 h, the account reached 26,000 followers and offered a platform for testimonies both against ‘ABZ’ and other individuals (see ). Each of the posts was originally published in English and initially targeted the AUC community, but later posts were translated into Arabic. This was crucial for the spread of the account since English is considered to be an elitist language in a society where Arabic is the main language. This step transformed a singular rally against ‘abz’ into wider activism against sexual harassment in Egypt and prevented labelling of sexual harassment as ‘rich people’s’ or ‘AUCian problem’.

Figure 2. More than 10 testimonies against ABZ (6 July 2020). The image of the woman supporting the leg is from giselledekel.format.com (reverse image search). Note the use of English and Arabic, the use of bright colours and different typographical features.

Some might perceive Assault Police as a delayed response or a delayed spinoff to #Me Too. However, whereas they share the medium and the goals, there are many differences. Firstly, the Egyptian spinoff to #Me Too had already taken place in the form of #Ana Kaman (literally translation of ‘Me too’). Instead, Assault Police comes as a new step for activists to expose sexual violence, and, as we described previously, it was not the first movement. Secondly, while #Me Too started by actress Alyssa Milano, and her fame helped the hashtag to spread, Assault Police (report abz) started as an anonymous account with no star power. Nadeen, a 22-years-old student at the American University in Cairo decided to expose a college student who allegedly assaulted women. She was unknown to anyone, and the account became viral and famous only because of the stories shared on it. Finally, after the success the account had in the case of ABZ, the account expanded its focus and became an account that brings up other new cases such as the Fairmont case. This shift protected the account from becoming one trend among many trends competing for the spotlight, especially in a country like Egypt with many daily events politically and economically. In other words, the account became a trend-maker, not a trend itself, which means a longer longevity and the ability to create loyal followers.

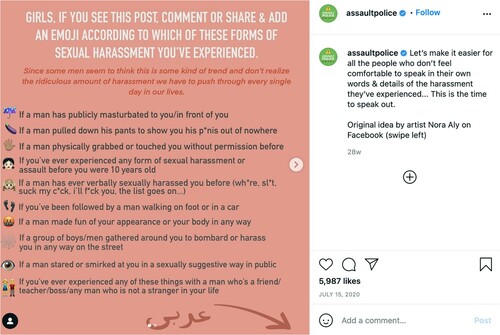

At a later stage Assault Police addressed further objectives other themes such as raising awareness (). It also became a venue for posting personal victim testimonies (). In addition, Assault Police offered outreach advocacy, started to cover other cases and provided legal and psychological aid to victims. The account turned its focus from a one single issue account into a platform against violence against women in Egypt. To summarise, the posts of the account can be divided into the following categories: exposing abusers, raising awareness, partnership with other entities (lawyers, psychologists) and victim testimonies.

Figure 3. Post asking to comment with a specific emoji, signifying different forms of harassment (15 July 2020). The emojis are colourful and are connected to the behaviours described. The appeal is in white capitals, the note on the ‘ridiculous amount of harassment' in red italics.

Figure 4. One of the six portraits of victims, including two men, posted on 18 July 2020. The portraits and textual testimonies appear to be in a white notebook. Some text is underlined. The texts are accompanied by a drawing of a victim in black and red, and a white, bright halo. The victim in this portrait looks at us. Artwork by Nada Elian is explicitly mentioned.

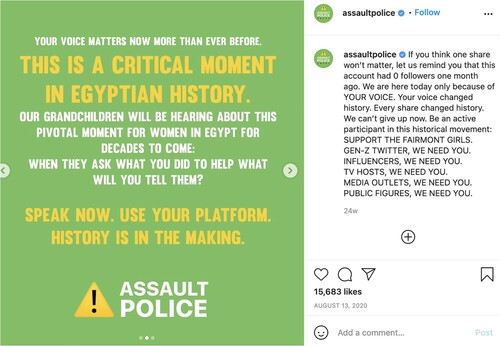

Then, on July 26, a post was published on the Fairmont case: several videos circulating on the Internet of ‘a group of upper-class men’ who have raped ‘multiple girls in the past 10 years’. The account went offline, as Police Assault became subject of violent threats. On August 13, a post was published stating ‘WE ARE NOT AFRAID’, ‘THE FIGHT IS NOT OVER’ (see ).

Figure 5. Post after being offline a while, using capitals explaining how Assault Police perceives its role (August 13).

Up to that point, the creator(s) of the account had remained anonymous. This changed on 20 August, when the 22-year-old philosophy major, Nadeen Ashraf posted a video of herself in which she speaks about why she actually started the account. Putting a face on the account helped it to expand to what it is now and contributed to a creation of trust which made cooperation between the account’s contributors and NGOs possible. Moreover, the video by Nadeen Ashraf matched the message and the frame of the account to the issue of the silence regarding sexual assault.

Diagnostic, prognostic and motivational framing

In dealing with the ‘ABZ-case’, the framing of the case did not only stop on the diagnostic framing by identifying the problem and suggesting who to blame. Several posts call for the audience not to attack ABZ in person or stalk his family. This plea, combined with the offer for legal aid to victims who wished to file reports against ABZ, shows a prognostic framing of the tools and strategies to tackle the case of ABZ. Even the first name of the account ‘Reportabz’ presented a solution by itself.

Furthermore, Assault Police does not get conferential with the government. In fact, the account supports and praises state’s initiatives to tackle sexual violence. For example, the account praised the step taken by the Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madoboly when he approved a law that guarantees the protection of the secrecy of the witness data (law No 177/2020). Assault Police also addresses the need for reporting of social media accounts and making people behind them accountable (see ).

Figure 6. Exposing a practice of some accounts that men use to share videos of themselves while sexual harassing women (September 20). The number of views is highlighted with red circles.

In addition, the account celebrates the law with a post saying, ‘We have officially amended the Egyptian law’ (July 8) the post also stated in capital letters:

‘THIS IS HOW POWERFUL YOUR VOICES ARE, KEEP SHARING, KEEP TALKING ABOUT THIS. CHANGE IS COMING’.

The account uses the three types of framing, for raising awareness it allows victims to share their testimonies regarding sexual abuses they have been victim of. Sometimes it shows why harassment takes place, so it takes a diagnostic role, for example in the posts regarding ‘gray area rape’ (September 11). These posts focus on the different balances of power that would affect consent. On other occasions, it calls for bystanders to step in and help the victim. An example of this relates to the Fairmont-case, when there was a threat that the victim’s name would be exposed. The account asked its followers not to share the name of the victim. Moreover, a motivational frame is used when the account asks the followers to share the victims’ stories or sharing the news of the accused men in the Fairmont-case and sharing their photos in the account after they got arrested. Again, the motivational frame here encourages the followers to participate and showing them that success is within the grasp.

Another framing process recognised by Snow (Citation2013) is frame alignment, which takes place when a social movement connects its goal with other organisations or source providers who will contribute to their campaigns. Assault Police collaborated with a psychiatrist who provided free assistance to victims of sexual violence (post of October 20). The clearest example of a frame alignment is the account hosting a talk with Nehad Abu El Komsan who addresses the law and how the victims can seek litigation. Abu El Komsan is the president of ECWR, the first NGO, who started fighting sexual harassment in 2005.

Assault Police, by January 2021, expanded their framing of the issue they are fighting to include discrimination against transgender, discrimination against women in sport and marital rape (see ), and still exposing new sexual predators.

Conclusion

Assault Police is an interesting example for online advocacy, showcasing modern media-based anti-sexual violence initiatives. The initiative, which started as an account focusing on a single issue developed to be an online initiative with known leaders and known collaborators and a clear strategy to ultimately fight various forms of violence against women, using a wide selection of tools. The Instagram account took a unique approach that differs from previous, more traditional movements and acted as an agent for change. The account focused primarily on criminal justice for victims, but over time the issues addressed kept evolving to reach the core issue, which is that it is discrimination (sexism) that leads to violence. Even though the account started by naming and shaming one single male student, it expanded its list of claims to cover transgender issues, discrimination against women in sports (see ) and an imbalance of power between men and women in general.

Finally, the Assault Police initiative shows the ability to adapt and evolve not only regarding framing their claims but also according to the nature of the medium which they are using. Instagram is a visual-based platform, which requires Assault Police to keep followers visually engaged. So far, the initiative has managed to use visual aids from memes to screenshots to artwork to build their claims regarding sexual violence against women. Our data and analyses were focused on the posts, not on the followers, which might be another interesting topic to examine. The question remains, though, whether Assault Police can survive the lifespan of trends in social media. We can only wait and see.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers of this essay for their comments and feedback as well as the editors of this special issue for their support. The authors express their gratitude to Nadeen Ashraf, the initiator of the Assault Police Instagram account, for consenting to the re-use and publication of screenshots featuring the account’s content.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The day of releasing this article to press, 29 September 2021.

References

- Abdelmonem, A. (2016). Anti-sexual harassment activism in Egypt: Transnationalism and the cultural politics of community mobilization [Doctoral dissertation]. Arizona State University. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/79584115.pdf.

- Abdelmonem, A. (2020). Disciplining bystanders: (anti)Carcerality, ethics, and the docile subject in HarassMap’s ‘the harasser is a criminal’ media campaign in Egypt. Feminist Media Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1785911

- Abdelmonem, A., & Galán, S. (2017). Action-oriented responses to sexual harassment in Egypt. Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, 13(1), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1215/15525864-3728767

- Amar, P. (2011). Turning the gendered politics of the security state inside out? International Feminist Journal of Politics, 13(3), 299–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2011.587364

- Assaultpolice [@assaultpolice]. (2021). Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/assaultpolice/?hl=en.

- BBC. (2005). Egypt anger over ‘grope attacks’ (2005, June 1). BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/4600133.stm.

- BBC. (2014). Egypt arrests seven over Tahrir square sexual assaults (2014, June 9). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27762144.

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Connell, R. W. (1990). The state, gender, and sexual politics. Theory and Society, 19(5), 507–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00147025

- El Deeb, B. (2013). Study on ways and methods to eliminate sexual harassment in Egypt. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (U.N. Women). https://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/gender-sexuality/un_womensexual-harassment-study-egypt-final-en.pdf.

- Fahmy, A., Hamdy, E., & Badr, A. (2014). Towards a safer city: Sexual harassment in greater Cairo: Effectiveness of crowdsourced data. Harassmap. https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/harassmap/media/HarassMap%20Egypt/Towards%20a%20Safer%20City_full%20report_EN.pdf.

- Fahmy, S. S., & Ibrahim, O. (2021). No memes no! Digital persuasion in the #MeToo era. International Journal of Communication, 15, 2942–2967.

- FIDH, New women foundation, The uprising of women in the Arab world, & Nazra for feminist studies. (2014). Egypt keeping women out: Sexual violence against women in the public sphere https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/egypt_women_final_english.pdf.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harper and Row.

- Hammad, H. (2017). Sexual harassment in Egypt: An old plague in a new revolutionary order. GENDER - Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesellschaft, 9(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.3224/gender.v9i1.04

- Harassmap. (n.d.). Harassmap.org: Who we are. https://harassmap.org/en/who-we-are.

- Hassan, R., Komsan, N., & Shoukry, A. (2008). ‘Clouds in Egypt's sky’, sexual harassment: From verbal harassment to rape. The Egyptian Center for Women's Rights. https://www.endvawnow.org/uploads/browser/files/ecrw_sexual_harassment_study_english.pdf.pdf.

- Heijthuyzen, M. (2018). Sexual violence and its resistance in post-revolutionary Egypt: At the intersection between authoritarianism and patriarchy. Law, Social Justice & Global Development, 21(SI), 1. https://doi.org/10.31273/LGD.2018.2105

- Herrold, C. E. (2016). NGO policy in pre- and post-Mubarak Egypt: Effects on NGOs’ roles in democracy promotion. Nonprofit Policy Forum, 7(2), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2014-0034

- Hunt, T. (2020). Mapping the Egyptian women’s anti–sexual harassment campaigns. In R Stephan & M M. Charrad (Eds.), Women rising (pp. 245–258). New York University Press.

- Jansma, N. (n.d.). Noa Jansma: #dearcatcallers. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from https://www.noajansma.com/dearcatcallers.

- Kelly, L. (1988). Surviving sexual violence. Polity Press.

- Kingsley, P. (2014, June 10). Seven arrested for sexually assaulting student during Tahrir celebrations. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/09/seven-arrest-sexual-assault-student-tahrir-square-sisi-inauguration.

- Kirollos, M. (2013, June 16). Sexual violence in Egypt: Myths and realities. Jadaliyya. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/29110/Sexual-Violence-in-Egypt-Myths-and-Realities.

- Krug, E. G., Dahlberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A., & lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/full_en.pdf?ua=1.

- Langohr, V. (2013). This is our square: fighting sexual assault at Cairo protests. Middle East Report, 268, 18–25.

- Loney-Howes, R., Mendes, K., Fernández Romero, D., Fileborn, B., & Núñez Puente, S. (2021). Digital footprints of #MeToo. Feminist Media Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1886142

- Mohamed, A. S. (2012). On the road to democracy: Egyptian bloggers and the internet 2010. Journal of Arab & Muslim Media Research, 4(2), 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1386/jammr.4.2-3.253_1

- Nordenson, J. (2017). Online activism in the Middle East: Political power and authoritarian governments from Egypt to Kuwait. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Rizzo, H., Price, A., & Meyer, K. (2012). Anti-Sexual harrassment campaign in Egypt. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 17(4), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.17.4.q756724v461359m2

- Skalli, L. H. (2014). Young women and social media against sexual harassment in North Africa. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2013.858034

- Snow, D. A. (2013). Framing and social movements. In D. A. Snow, D. Della Porta, B. Klandermans, & D. McAdam (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of social and Political movements (pp. 1780–1784). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm434.

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1(1), 197–217.

- Tadros, M. (2015). Mobilising against sexual harassment in public spaces in Egypt: From blaming ‘open cans of tuna’ to ‘the harasser is a criminal’. EMERGE Case Study 8, Promundo-US, Sonke Gender Justice and the Institute of Development Studies.

- Vijay, D., & Kulkarni, M. (2012). Frame changes in social movements: A case study. Public Management Review, 14(6), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2011.642630