ABSTRACT

When health systems are overwhelmed during a public health crisis regular care is often delayed and deaths result from lapses in routine care. Indigenous primary healthcare (PHC) can include a range of programmes that incorporate treatment and management, prevention and health promotion, as well as addressing the social determinants of health (SDoH) and a focus on redressing health inequities. We examined how Indigenous PHC mobilises and innovates during a public health crisis to address patient needs and the broader SDoH. A rapid review methodology conducted from January 2021 – March 2021 was purposefully chosen given the urgency with COVID-19, to understand the role of Indigenous PHC during a public health crisis. Our review identified five main themes that highlight the role of Indigenous PHC during a public health crisis: (1) development of culturally appropriate communication and education materials about vaccinations, infection prevention, and safety; (2) Indigenous-led approaches for the prevention of infection and promotion of health; (3) strengthening intergovernmental and interagency collaboration; (4) maintaining care continuity; and (5) addressing the SDoH. The findings highlight important considerations for mobilising Indigenous PHC services to meet the needs of Indigenous patients during a public health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

Primary healthcare (PHC) is a core component of the health system (World Health Organization Alma-Ata, Citation1978), and a first, or only, point of contact for families over time with professionals who can facilitate access to specialist care and support. PHC is a critical foundation of health and wellbeing at every stage of life (WHO Alma-Ata, Citation1978) and crucial during public health crises. PHC marks the beginning of a continuous health process (Muldoon et al., Citation2006; Wright & Mainous III, Citation2018) being inclusive of health promotion (e.g. hand hygiene), disease prevention (e.g. vaccinations), health maintenance, education, and rehabilitation (WHO Alma-Ata, Citation1978). The 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) World Health Report called for a worldwide renewal of PHC, including reorientation towards person-centred care rather than focusing on the presence or absence of disease alone (WHO Alma-Ata, Citation1978; WHO World Health Report, Citation2008). Furthermore, community participation is a key principle of PHC and patients are encouraged to participate in making decisions about their own health, in identifying the health needs of their community, and in considering alternative approaches to addressing those needs (van Weel & Kidd, Citation2018).

Addressing the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) through PHC

Increasing focus on health inequities has brought renewed attention to two related health policy discourses which are inextricable from each other—PHC and the SDoH (Rasanathan et al., Citation2011). The Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) defined the SDoH as ‘the structural determinants and conditions of daily life responsible for a major part of health inequities between and within countries (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Citation2008).’ SDoH provide a lens that illuminates the systemic causes of health inequities while identifying ways to address them; PHC is well-positioned to address the SDoH in that health equity is a core value of PHC systems (Baum et al., Citation2013; Pinto & Bloch, Citation2017; Rasanathan et al., Citation2011). Strong systems of PHC have demonstrated their ability to advance health equity, lower health costs, and improve overall population health (Starfield et al., Citation2005; van Weel & Kidd, Citation2018). Despite the significant overlap between the principles of PHC and the need to better address the SDoH, there is still a substantial gap in both the understanding and implementation of PHC to effectively close gaps in health equity (Andermann, Citation2016).

Disparities in effective PHC services are most pronounced for Indigenous populations worldwide for whom the SDoH disproportionately impacts health (Reading & Wien, Citation2009; United Nations, Citation2007). Indigenous people across different countries descent from the populations who inhabited the country before the arrival of European settlers, and how irrespective of their legal status, retain their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions (United Nations, Citationn.d.). Maybury-Lewis (Citation2002) states that ‘Indigenous peoples are defined as much by their relations with the state as by any intrinsic characteristics that they may possess.’ Improving population health among Indigenous people across the globe requires addressing the SDoH through PHC, including a focus on health promotion and public health initiatives (Harfield et al., Citation2018; Rasanathan et al., Citation2011). Stemming from the longstanding and continuing impacts of colonisation, inequalities in physical, social, and mental health are amplified by the exclusion of Indigenous peoples in mainstream PHC services (Horrill et al., Citation2018; Reading & Wien, Citation2009). Indigenous peoples are often unable to access PHC to have their needs effectively met (Davy et al., Citation2016; Harfield et al., Citation2018; Kim, Citation2019; Reading & Wien, Citation2009). In response, exemplar models of Indigenous PHC organisation that adequately meet the needs of Indigenous peoples and communities have been promoted to reaffirm opportunities for Indigenous health advancement (Harfield et al., Citation2018). Indigenous-driven and -led PHC services derive from the principles and values of whom they serve (Harfield et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, Indigenous PHC services are characterised as culturally appropriate, holistic, accessible, and self-determined, and can include a range of comprehensive programmes that incorporate treatment and management, prevention and health promotion, as well as addressing the SDoH and how they contribute to health inequities (Harfield et al., Citation2018).

Role of PHC during a public health crisis

While both PHC and public health are interconnected parts of providing equitable healthcare, they often operate in relative isolation which is illuminated during times of health system stress such as during a pandemic. Pandemics shift the way in which PHC is delivered whereby regular care is often postponed (Rawaf et al., Citation2020). During the current global pandemic of COVID-19, PHC services are managing the reallocation of healthcare resources and the after-effects of patients who are suspected to have or confirmed to have COVID-19 (Rawaf et al., Citation2020). When health systems are overwhelmed during outbreaks, deaths caused by lapses in routine care can increase dramatically (PHCPI, Citation2018). Despite knowing this, healthcare systems necessarily shift their focus and resources to emergency and intensive care services (Blumenthal et al., Citation2020). This situation is further exacerbated for Indigenous PHC, which already faced the realities of under-resourcing, the aforementioned inequities in SDoH, and jurisdictional complexities in health service responsibilities. These inequities were glaringly apparent during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic when Indigenous people made up approximately 10% of all deaths from H1N1 (Driedger et al., Citation2013) and thus highlight the need to reconsider approaches to sustain Indigenous PHC while aiming to support public health goals. There are important lessons shared in the literature on how Indigenous PHC mobilises to address population needs during a public health crisis, and which components of a PHC system facilitate and enable Indigenous PHC to continue to provide services. This review aims to identify, appraise, and summarise emerging research evidence to support recommendations to strengthen Indigenous PHC responses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A rapid review methodology was purposefully chosen given the urgent need to understand the role of Indigenous PHC in a public health crisis. The review was undertaken from January to March 2021 by the Indigenous Primary Health Care and Policy Research (IPHCPR) Network (www.iphcpr.ca) and informed by rapid review methods outlined by the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (Dobbins, Citation2017). Rapid reviews provide a timely, valid and balanced assessment of available evidence related to a particular policy or practice issue (Watt et al., Citation2008). The process for a rapid review of evidence is characterised by developing a focused research question, a less developed search strategy, evidence searches, and then more simplified data extraction and quality appraisal of the identified literature when compared to traditional systematic reviews (Watt et al., Citation2008). The following questions were used to guide the rapid review: How does Indigenous PHC mobilize to address patient and community needs during a public health crisis? What are the components (organization, systems, programs, providers, communities) of the response? A protocol has been registered with the University of Alberta Education and Research Archive (https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-bpf3-by13) and published on the Open Science Framework Registries (osf.io/3tkgr).

Search strategy

The search was conducted on November 19th, 2020 and had no exclusion criteria around dates. The earliest manuscript that was reviewed was from 1946. The search strategy was set to identify PHC responses to pandemics and epidemics among Indigenous populations, specifically structures of service delivery, health policy, resource allocation, and organisation of care on Indigenous health outcomes. A list of Indigenous populations identified in the sources reviewed, who are called, variously, Indigenous, tribal, native, or Aboriginal in different parts of the world, can be found in Appendix A. Two search term filters were used: population and outcome. The population filter was built to identify international Indigenous populations by combining general, country-specific, and tribe-specific search terms, while the outcome filter was developed to include COVID-19, general pandemics, and general epidemics; the results of these two searches were combined with the Boolean operator ‘AND.’ The search was restricted to English, French, and Spanish languages. Of note, because of the limited research in this area, the search strategy did not filter for countries that have established Indigenous PHC services. MeSH terms and subject headings were included synergistically in the search for robustness. Searches were conducted in Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases by researchers at the Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit. Results of the searches were exported to Covidence systematic review software, where duplicates were removed. Search strategies are available in Appendix A.

Selection criteria

The Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Design (PICOD) framework was employed to develop the eligibility criteria for this rapid review (see ). Eligibility criteria were defined as follows: (1) focused exclusively on Indigenous peoples in Canada (First Nations, Métis, and/or Inuit) and other Indigenous populations across the globe, (2) focused on pandemics or epidemics involving influenza-like infections (CDC, Citation2018; World Health Organization Europe, Citationn.d.), (3) focused on the PHC response during a public health crisis in Indigenous communities, and/or (4) identified how core PHC functions were mobilised during the public health crisis examined, including collaboration and coordination between community departments (e.g. housing, health, family and social services, etc.) and addressing the social determinants of health, and/or (5) focused on Indigenous models of health and wellness, including the role of culture and Indigenous ways of knowing. Studies were excluded if they reported on non-communicable diseases, sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs), foodborne illnesses or other non-influenza-like infectious diseases. Primary empirical studies, theoretical studies, reviews of empirical studies and implementation studies were also included. For title and abstract screening, each source was independently evaluated twice by three authors (KF, AS, AH) and any disagreements were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached.

Table 1. PICOD statement.

Grey literature search

An additional search was also conducted using Google and Google Scholar to identify studies not published in indexed journals and grey literature sources. Studies relating to PHC initiatives undertaken by governmental and/or Indigenous organisations may be disseminated through websites, news articles or open-access databases. The search was restricted by country to capture relevant data from Canada, the United States, circumpolar countries, Australia, and New Zealand. The grey literature search was restricted to the countries listed above as all but one primary research article from the systematic search was either from New Zealand, Australia, or Canada. In addition, due to the rapid timeframe of this review, and the need to provide timely evidence and guidance to key stakeholders working in Indigenous PHC, we limited the countries we searched and only looked to the first 50 results that were generated in google which were then screened for inclusion. The same inclusion criteria were applied to the grey literature search. Grey literature was excluded if it was a narrative or anecdotal account of Indigenous peoples’ and/or organisations’ experiences during a public health crisis with no further discussion on mobilising or responding to patient and/or community needs during a public health crisis.

Data extraction

Data was extracted into a data extraction form in Microsoft Excel that included the source title, publication date, location, description of the public health crisis, the PHC setting, health outcomes measures, and SDoH supported (refer to Appendix B for the data extraction form) by the same three researchers. Two authors (KF, AS) performed full-text reviews of selected screened articles to verify which met the inclusion criteria.

Data synthesis

A thematic analysis was undertaken using Maxwell’s (Citation2005) and Miles and Huberman’s (Citation1994) qualitative analysis technique of descriptive and pattern coding. Extracted data was open-coded by two researchers (KF, AS) and then categorised to identify patterns, similarities, and differences throughout the data. Disagreements in data analysis were resolved through discussion until researchers (KF, AS) reached a consensus. Themes were reviewed and verified by a public health and health policy researcher (SM), an Indigenous PHC provider (LC), and an Indigenous health services researcher (CB).

Quality assessment

The quality of each study was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). Quality assessment was completed by one reviewer (EP) and verified by a second reviewer (TK); any conflicts were resolved through consensus. An adapted JBI Text and Opinion tool from the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health was employed to reflect Indigenous Ways of Knowing in the quality evaluation of these studies (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools & National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, Citation2020). This required the inclusion of two additional questions to the JBI appraisal tools. Articles were scored high, moderate or low quality following the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools & National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (Citation2020) guidelines. Grey literature was not critically appraised for this rapid review.

Findings

Study characteristics

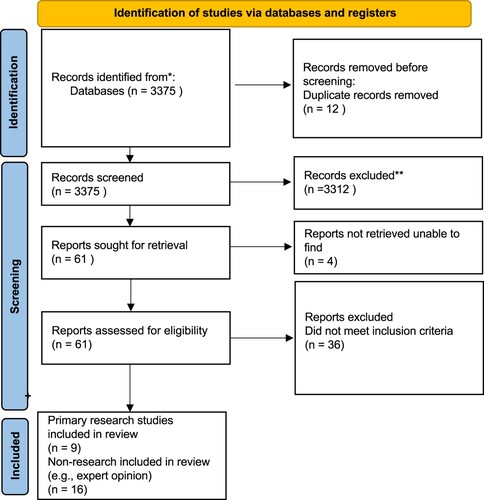

A total of 3387 records were identified in the peer-reviewed literature search which was reduced to 3375 after removing duplicates. After title and abstract screening, a total of 61 articles remained for full-text review. Following full-text review, a total of 25 peer-reviewed primary research and opinion, commentary or report articles met inclusion criteria and underwent data extraction (refer to the PRISMA flow chart in ). From the grey literature, a total of 22 sources met inclusion criteria (Page et al., Citation2021). The peer-reviewed studies (), commentaries/opinion pieces () and grey literature () included Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, and South American Indigenous populations and varied between the H1N1 and COVID-19 pandemic public health crises. Noteworthy, while other public health crises were included in the search (e.g. SARS, MERS) there were no records outside of H1N1 and COVID-19 that fit our inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2. Peer-reviewed primary research.

Table 3. Peer reviewed opinion, commentary, and reports.

Table 4. Grey literature sources.

Themes

Our synthesis yielded five main themes that highlight the role of Indigenous PHC during a public health crisis: (1) development of culturally appropriate communication and education materials about vaccinations, infection prevention, and safety; (2) Indigenous-led approaches for the prevention of infection and promotion of health; (3) strengthening intergovernmental and interagency collaboration; (4) maintaining care continuity; and (5) addressing the SDoH. summarises the main components of an Indigenous PHC system such as organisations, systems, programmes, providers, and communities that facilitate and enable PHC delivery during a public health crisis.

Table 5. Components of a Primary healthcare (PHC) system.

Development of culturally appropriate communication and education materials

As stated in the Alma-Ata declaration, PHC ‘includes education concerning sanitation, immunization, prevention and control of endemic disease’ and also ‘addresses the main health problems in the community, providing promotive, preventative, curative and rehabilitative services accordingly’ (WHO Alma-Ata, Citation1978). Based on these components of the declaration, public health messaging, health promotion, infectious disease communication and education is an important role for PHC. While many sources discussed culturally appropriate communication and education, most of the time they did not directly link back to PHC or PHC was not a part of the development of these materials. However, it is understood that communication and educational materials that were developed, were implemented and carried through in PHC settings.

Several empirical studies included in this rapid review detailed lessons learned from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in relation to effective communication and education which provided an opportunity for informing PHC responses to the current crisis of COVID-19 (Charania & Tsuji, Citation2011; Charania & Tsuji, Citation2012; Driedger et al., Citation2013; Gray et al., Citation2012; Herceg et al., Citation2010; Massey et al., Citation2009; NCCIH Communications Officer, Citation2016; Richardson et al., Citation2012; Rudge & Massey, Citation2010). The H1N1 pandemic highlighted a need to localise communication and engagement with Indigenous communities so that Indigenous peoples can trust the messages being conveyed to them, know where to go to access healthcare services, and are well-prepared to support themselves and their families in a public health crisis (Charania & Tsuji, Citation2011; Gray et al., Citation2012; Massey et al., Citation2009; NCCIH Communications Officer, Citation2016). It was reported that during the H1N1 pandemic, information shared by Canadian health agencies with Indigenous communities was often inconsistent, misleading, or contradictory (NCCIH Communications Officer, Citation2016). Learning from the H1N1 outbreak, several local Indigenous health service organisations mobilised during the COVID-19 pandemic through community engagement and promoting culturally-relevant and safe communication and education about the virus to communities; which are necessary components of a successful pandemic response (Henderson, Citation2020; Kerrigan et al., Citation2020; First Nations Health Authority).

Of the sources included, there was strong evidence in support of reliable and culturally-appropriate communication around vaccinations, infection prevention, and safety within PHC settings to address patient needs during a public health crisis (Crooks et al., Citation2020; Finlay & Wenitong, Citation2020; Gray et al., Citation2012; Kennedy, Citation2020; Kerrigan et al., Citation2020; Massey et al., Citation2009; Moodie et al., Citation2020; NCCIH Communications Officer, Citation2016; NSW Health, Citation2019; Roberts, Citation2020; Rudge & Massey, Citation2010). Scholars highlighted the need for information about virus spread, infection prevention and vaccination from sources Indigenous communities could trust (Gray et al., Citation2012; NCCIH Communications Officer, Citation2016). One moderate quality empirical study, a commentary and a few grey literature sources described initiatives developed by health sectors and Indigenous health organisations that engaged Indigenous community leaders and/or communities during H1N1 and COVID-19 in the creation and dissemination of important messages related to safety, infection prevention, stress reduction and health promotion (e.g. pre-existing chronic conditions) (Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020; Kerrigan et al., Citation2020; Roberts, Citation2020; Rudge & Massey, Citation2010). For example, in a news article by Draaisma (Citation2021) the author described the design of educational materials including videos, fireside chats and other resources that draw upon the expertise and wisdom of community members, elders, knowledge keepers, traditional practitioners, and Indigenous physicians, to support Indigenous peoples in northern Ontario to make informed choices about the COVID-19 vaccines. These resources are shared on the Maad’ookiing Mshkiki — Sharing Medicine website, developed in collaboration with several Indigenous-focused organisations and groups located in Toronto, Ontario including the Centre for Wise Practices in Indigenous Health at Women’s College Hospital, the Indigenous Primary Health Care Council, Anishnawbe Health Toronto, the Indigenous Health Program at University Health Network and Shkaabe Makwa — an Indigenous-focused branch of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

While there were several references about the importance of communication in native Indigenous language (Kerrigan et al., Citation2020), emphasis was placed on delivering culturally safe and culturally relevant communication that went beyond translation to Indigenous languages; rather applying modes of communication that reach Indigenous peoples (e.g. through storytelling), and providing customised information resources that were grounded in Indigenous histories, cultures and worldviews (Groom et al., Citation2009; Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020; NCCIH Communications Officer, Citation2016). Application of this was noted in several non-empirical sources including commentaries, opinion pieces and news articles published during the COVID-19 pandemic that described the development of culturally relevant materials on infection prevention and vaccines that are centred on Indigenous values and knowledge (Draaisma, Citation2021; Dyer, Citation2020; Roberts, Citation2020; Saskatchewan Health Authority, Citation2021a). For example, a grey literature source describing the COVID-19 response in Navajo Nation shared posters with public health messages such as ‘how to safely hold a ceremony’ and ‘how to safely take part in a sweat lodge.’ (Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020). In another source, recommendations for infection control were presented for cultural ceremonies in the province of Saskatchewan (Saskatchewan Health Authority, Citation2021a). Moreover, these types of resources can be equally promoted by providers in the mainstream PHC system to support effective communication and messaging to Indigenous patients. Although many of the sources cited in this theme were Indigenous-focused, learnings from H1N1 and the current COVID-19 pandemic have strongly suggested that Indigenous-led approaches are often quicker to respond and more effective (Banning, Citation2020a; Crooks et al., Citation2020; Dyer, Citation2020; Finlay & Wenitong, Citation2020).

Indigenous-led approaches for prevention of infection, meeting care needs and promotion of health

Some sources identified where mainstream supports were inadequate and Indigenous health organisations and services stepped in to fill the gaps using Indigenous-led approaches (Dyer, Citation2020; Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020; Johnsen, Citation2020; Kerrigan et al., Citation2020; Roberts, Citation2020). For example, one article discussed why COVID-19 transmission was lower than expected in Australian Indigenous communities from the perspective of an Aboriginal Medical Services Officer. Their perspective was that while the government was focused on public health orders such as restricting travel to protect Indigenous communities, Indigenous health groups and organisations focused on messaging to community to promote social distancing and hygiene practices (Roberts, Citation2020).

Several sources described the way Indigenous health service organisations and communities mobilised to support the health and social needs of communities. For example, Navajo Nation and providers from Indian Health Services (IHS) medical facilities and Urban Indian Health Programs worked together on disease prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic by distributing personal and protective equipment (PPE) and by implementing a community health workers model (CHW) (Rosenthal et al., Citation2020; Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020). Several sources described the importance of training and hiring local CHWs (Rosenthal et al., Citation2020) as a way to utilise the strengths and knowledge within the community (Massey et al., Citation2009). CHWs support the delivery of information related to safety and protection (e.g. about vaccines, how to prevent the spread of the virus), assess the risks of mental health distress, self-management for those living with a chronic disease, and promoting the health and social well-being of individuals. CHWs were promoted as a bridge for patients to support enhanced access to necessary health and mental health services and connection to other PHC services (Fitts et al., Citation2020; OCHA, Citation2020; Rosenthal et al., Citation2020; Rudge & Massey, Citation2010). The importance of CHWs was highlighted in a commentary that discussed the risk incurred by rural and remote health services that rely heavily on short-term outreach healthcare providers who come from outside the community which increases the risk of introduction of infection and transmission (Fitts et al., Citation2020). Thus, CHWs would mitigate this risk. However, the sources reviewed did not provide information about how this could be done, such as with the allocation of funding and resources to support their role.

Additionally, several sources outlined how partnerships between health sectors and Indigenous organisations led to the development of Indigenous-specific preparedness frameworks for rapid testing, isolation, and limiting spread (Dreise & Ali, Citation2020; Henderson, Citation2020). There were several examples describing the implementation of rapid testing which included mobile testing units for Indigenous peoples throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in rural communities (Cousins, Citation2020; Johnsen, Citation2020; Saskatchewan Health Authority, Citation2021b). In addition, commentaries and grey literature sources revealed successful efforts by health authorities, PHC, CHWs, and community members to decrease transmission of COVID-19 using public health messaging and isolation centres (sometimes supported by PHC) (Banning, Citation2020b; Close & Stone, Citation2020; Dreise & Ali, Citation2020; Dyer, Citation2020; Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020; Kaplan et al., Citation2020; Massey et al., Citation2011; Moodie et al., Citation2020). In the declaration of Alma-Ata, they state PHC ‘requires and promotes maximum community and individual self-reliance and participation in the planning, organization, operation and control of PHC, making the fullest use of local, national and other available resources; and to this end develops through appropriate education the ability of communities to participate.’ Community-led isolation centres and other community-based programmes then are a component of primary healthcare.

Furthermore, the health and social needs of Indigenous peoples were supported by relying on PHC community-based programmes and services for adults, youth and families (Australian Government Department of Health, Citation2020; Jones, Citation2021). One innovative programme in Navajo Nation called the colored paper project had community staff members drive past Elders’ homes twice daily (Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020). The Elders would use coloured paper in their windows to signify their needs, green signified that the Elder did not need support, red signified the need for medical support, yellow signified the need for resources or supplies (e.g. toilet paper), and blue signified the need for company or social support (Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020). The sources identified in the review describe outreach services and community-initiated responses that were implemented by Indigenous health service organisations and communities often in partnership with the health sector to slow down the spread of the virus in communities, however no specific outcome measures were reported on the success of these interventions.

Strengthening intergovernmental and intersectoral collaboration for PHC delivery

Several high-quality sources included in this rapid review described the importance of strong intergovernmental collaboration and relationship between provincial/state/territorial government health agencies and local health service organisations to achieve the goals of PHC in the context of a pandemic (Charania & Tsuji, Citation2012; Fitts et al., Citation2020; Groom et al., Citation2009; Henderson, Citation2020; Herceg et al., Citation2010; Jenkins et al., Citation2020; OCHA, Citation2020; Richardson et al., Citation2012). In a qualitative study, consistent and regular intergovernmental meetings with Indigenous communities fostered trust among stakeholders during the H1N1 pandemic and allowed for clear communication and transparency which may not have been possible without the mobilisation of local Indigenous health services (Gray et al., Citation2012). During the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, the federal government worked with Indigenous Nations to provide funding and resources for communities to support their pandemic response. The need to strengthen collaboration, trust and relationships between the federal government and Indigenous Nations in the current pandemic context was described to not repeat past harms inflicted on Indigenous people from previous pandemics. The disturbing example that occurred during the H1N1 outbreak where the federal government sent body bags to four Manitoba First Nations communities instead of shipments of antivirals, hand sanitisers and flu kits is a notable example of what not to repeat in future public health emergencies (Driedger et al., Citation2013).

Maintaining care continuity

PHC services should help maintain care continuity during a pandemic, with continued access to other health services and supports (Laupacis, Citation2020). Scholars highlighted the importance of equitable, reliable and consistent access to regular health services for Indigenous peoples and communities during a public health crisis (Banning, Citation2020a; Charania & Tsuji, Citation2011; Charania & Tsuji, Citation2013; Cousins, Citation2020; Dyer, Citation2020; Henderson, Citation2020; Kaplan et al., Citation2020; Massey et al., Citation2009; First Nations Health Authority; Hengel et al., Citation2020; Johnsen, Citation2020). One source highlighted an excellent example of self-determination when they described how providers from Indian Health Services and Urban Indian health programmes in Navajo, Mississippi Choctaw Nation worked together to support routine care and ensure continued access to essential services by conducting household visits. The adoption of virtual care within some Indigenous health services was also reported to support continued access to services and supports during the COVID-19 pandemic (Business Partnerships Platform, Citation2020; Danila Dilba Health Service, Citation2020; Fitts et al., Citation2020; Divisions of Family Practice; Anishinabek News., Citation2020).

Addressing the social determinants of health

In a published presentation by the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, they highlight how the pandemic has impacted all social determinants of Inuit health making access to PHC more difficult as medical travel was impacted (Obed, Citation2021), this could be transferable to all Indigenous populations. Indigenous health service organisations and communities mobilised to support the health, social and economic needs of communities by developing and implementing culturally-relevant resources to promote the safety of Indigenous peoples (Dyer, Citation2020; Kerrigan et al., Citation2020; Rudge & Massey, Citation2010). As PHC is often inaccessible to Indigenous communities, examples of programming that addressed inequalities in physical, social, and mental health were noted. For example, virtual care and virtual health promotion, mobile testing and vaccine centres, and innovative programmes such as the colored paper project all provide better access to PHC services for Indigenous peoples (Cousins, Citation2020; Divisions of Family Practice, Citationn.d.; First Nations Health Authority, Citationn.d.; Hostetter & Klein, Citation2020; Johnsen, Citation2020; Saskatchewan Health Authority, Citation2021b). In British Columbia Canada, during the pandemic they launched the Virtual Doctor of the Day program, with physicians, including Indigenous providers, offering culturally safe PHC in a timely and accessible manner (First Nations Health Authority, Citationn.d.). Community healthcare workers are another great example in which SDoH are addressed as this role encompasses factors of care that include considerations and support around housing, and food security (Hernandez et al., Citation2020; OCHA, Citation2020). Thus, not only providing surface-level care during a pandemic but rather sustainable interventions tailored to the needs of the community. While there are several barriers to addressing SDoH in Indigenous communities, COVID-19 also provided opportunities for Indigenous communities to have autonomy in the pandemic response to create meaningful outcomes on the SDoH as highlighted above.

Discussion

Indigenous PHC service delivery models are defined by several characteristics including accessible health services, community involvement, culturally appropriate and skilled workforce, holistic healthcare and wellness, self-determination and empowerment, connection to culture, and coordination of intersectoral and multidisciplinary collaboration (Harfield et al., Citation2018; Montesanti et al., Citation2021). These unique characteristics demonstrate the importance of Indigenous PHC models in promoting and protecting the health of Indigenous communities during a public health crisis. Specifically, Indigenous PHC plays a key role by effectively communicating about infection prevention and vaccine safety to Indigenous patients and communities; offering rapid testing, administering vaccinations and personal protective equipment (PPE) to communities, working collaboratively across sectors, agencies, governments, and with other healthcare providers; and ensuring continuity of routine care for Indigenous peoples. Sources highlighted how Indigenous health service organisations worked directly with communities (leaders, Elders, Knowledge Keepers, youth) in the creation and dissemination of communication strategies and information resources to convey important messages related to safety, mental health, infection prevention, and protection of health. The findings also highlighted the need for delivering culturally safe and culturally relevant communication, engaging Indigenous communities in the planning of service delivery, and ensuring that the voices of communities are heard especially at a time when there is heightened stress and fears brought on by a public health crisis or emergency.

Key themes from the rapid review findings support aspects of Indigenous PHC service delivery which are known to effectively work. For instance, we found that maintaining care continuity was the focus of various PHC components, and research has shown that Indigenous peoples experience better overall health outcomes when care is not compartmentalised (Fraser et al., Citation2017). Intersectoral service coordination is also critical for ensuring a continuum of care across PHC and secondary care. Despite the widespread commitment to intergovernmental and intersectoral collaboration low levels of trust, legitimacy and goal consensus among collaborating entities impeded collaboration and relationship-building. Furthermore, developing culturally appropriate communications regarding infection prevention, safety, and mental health promotion was another prominent theme in the findings, and this is aligned with research that suggests that health information needs to be tailored to different population groups and acknowledge their social and cultural context surrounding their health (Van den Broucke, Citation2020).

The review findings also demonstrated how Indigenous PHC systems reorganised during a pandemic by establishing strong links to community-based programmes and services for children, youth and families, expanding home-based care, and improving access to care during the crisis, mainly through the hiring of CHWs. CHWs play an essential role in addressing risks to health and mental health in communities and delivering timely, accurate information about the crisis and ensuring that all patients or community members obtain access to culturally appropriate care and support (Rosenthal et al., Citation2020). Previous research studying the role of CHW during a public health crisis demonstrates that CHWs fulfil important and new service needs, and play meaningful roles in the context of strategies to improve the delivery of care (Schneider et al., Citation2008). There is a growing body of evidence that supports the role of Indigenous CHWs in providing valuable services and supports across health, wellness, and community support, including cancer prevention (Cueva et al., Citation2014), oral health (e.g. Braun et al., Citation2016), mental health promotion and substance use treatment (O'Keefe et al., Citation2021), and connecting patients to health or community resources (e.g. transportation services; Gampa et al., Citation2017). Indigenous CHWs also possess knowledge and understanding of local history, culture, community, and spirituality which may help maintain trust with community members. The building and maintenance of trust in communities is an invaluable component of the CHW model as the effects of colonialism and racism, both at institutional and individual levels, within the healthcare system have led to a lack of trust in the healthcare system for many Indigenous individuals and communities. Thus, CHWs represent a proven strategy for improving access to health services during a public health crisis, and their roles can be expanded to work closely with the PHC sector.

Research has shown that PHC delivery across some parts of the globe is characterised by prioritised narrow investments and disconnected systems, services, and providers that impede progress towards sustainable solutions for Indigenous PHC service delivery models and pose challenges to responding to crises that require an urgent and collaborative response (International Foundation for Integrated Care, Citation2020; Montesanti & Fayant, Citation2020; Valentijn et al., Citation2013). For Indigenous PHC models to be enacted during a public health crisis or emergency, governments need to reinforce financial commitments and responsibilities towards equitable PHC service infrastructure for Indigenous communities.

Additionally, governance is key to effective health emergency preparedness. A key supportive governance mechanism for PHC is participatory models that strengthen linkages between policymaking and community engagement; as well as successful approaches for Indigenous PHC must be anchored in the principles of self-determination for Indigenous peoples (United Nations, Citation2007). Direct involvement of community members in healthcare delivery strengthens public accountability in health systems and is a means to promote sustainability of pandemic supports provided through PHC. Sufficient community support enables preparedness strategies to be suited to the community’s needs and in turn, increases their likelihood of being sustainable. Conversely, lack of adequate community engagement contributes to low levels of community trust in mainstream health services and government, which has been shown to hamper PHC implementation, including critical emergency services (Bitton et al., Citation2019). Culturally-safe and culturally responsive care, along with the inclusion of Indigenous values in the design and delivery of healthcare services are important domains of responsiveness to consider during public health emergencies (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2021) and to ensure sustainability of PHC strategies or interventions. At a clinical level, strong Indigenous-focused strategies improve acceptability of and demand for PHC services. For instance, research conducted by authors on this paper (SM, LC) found that concerns surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine among Indigenous peoples in Canada stem from years of mistrust with the Canadian healthcare system (Goveas et al., Citation2021). Previous negative experiences with the mainstream healthcare system and government have repeatedly been found to create a barrier to accessing healthcare among Indigenous peoples. Contemporary experiences with racism and discrimination also impede the development of trusting relationships with mainstream healthcare providers. Furthermore, globally, Indigenous peoples advocate for the right to self-determination, development, and administration of health programmes. Self-determination is about enabling communities to build capacity and effectively address the factors that impact the health of Indigenous peoples (Auger et al., Citation2016).

This rapid review found limited evidence reporting specifically on the outcomes from promising strategies or approaches used in Indigenous PHC settings to prevent infection and protect health during a public health crisis. Of the sources included, findings primarily described the design and implementation process of different interventions and strategies. Nonetheless, the review provides a compelling case for research to describe emerging innovations within Indigenous PHC contexts in response to public health crises. This knowledge has the potential to inform and support health systems to be more resilient for future public health emergencies but also to meet the challenges faced by Indigenous populations across the globe. Of note, COVID-19 is more prevalent in the evidence base compared to H1N1 for Indigenous populations. Possible explanations include that Indigenous communities are more interested and able to share their experiences, previous pandemics may not have had as extensive data written and/or published, information is more readily shared online, and there has been considerable interest from academic journals to publish COVID-19 research and data.

Strengths and limitations

In order to address the challenges that Indigenous communities face with accessing PHC during a public health crisis, information needs to be succinctly synthesised for governments and policy and decision-makers to utilise for future planning. A strength of this review is that to the best of our knowledge, there is no published review that synthesises both primary sources and grey literature in this topic area. In addition, we took an international approach for best representation allowing for the results to be transferable across a variety of Indigenous populations. While we did try to capture Indigenous populations globally in our search terms, some Indigenous populations, tribes and communities may have been missed, along with any studies which were not presented in English. In addition, our grey literature search was limited in countries we searched (Canada, United States, circumpolar countries, Australia, and New Zealand) and only looked to the first 50 results that were populated in google. Further, our rapid review did not make any distinctions between Indigenous identities and groups.

Conclusion

The findings from this rapid review highlight the potential of Indigenous PHC services to mobilise and meet the needs of Indigenous patients during a public health crisis such as COVID-19. There have been frequent public health crises that have disproportionately affected Indigenous populations across the globe over the past decade or more. Approaches to re-orienting health services to respond to the pandemic require a supportive policy environment and inter-governmental relationship and collaboration. Innovations in health service delivery introduced to support health during the pandemic need to be maintained for fostering resilient health systems against future public health emergencies but also to be able to meet the needs of Indigenous peoples. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated most prominently that sovereignty, leadership, and knowledge of Indigenous communities is an essential foundation for public health during moments of crisis, and that building on existing relationships is a strong platform for service delivery.

Acknowledgements

We also wish to acknowledge Meghan Sebastianski (PhD) and Diana Keto-Lambert (MLIS) from the Alberta Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (AbSPOR) SUPPORT Unit Knowledge Translation Platform for their assistance developing a search strategy and conducting the searches for the academic literature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andermann, A. (2016). Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. Canadian Medical Journal Association, 188(17–18), E474–E483. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160177

- Anishinabek News. (2020, August 27). The North Bay Indigenous Hub sees continued success throughout the pandemic. Anishinabek News. https://anishinabeknews.ca/2020/08/27/the-north-bay-indigenous-hub-sees-continued-success-throughout-the-pandemic/.

- Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

- Auger, M., Howell, T., & Gomes, T. (2016). Moving toward holistic wellness, empowerment and self-determination for Indigenous peoples in Canada: Can traditional Indigenous health care practices increase ownership over health and health care decisions? Canadian Journal of Public Health, 107(4), e393–e398. https://doi.org/10.17269/CJPH.107.5366

- Australian Government Department of Health. (2020, June 12). Keeping remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities safe from COVID-19. Partyline. https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/partyline/article/keeping-remote-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-communities-safe-covid-19.

- Banning, J. (2020a). Why are Indigenous communities seeing so few cases of COVID-19? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(34), https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1095891

- Banning, J. (2020b). How Indigenous people are coping with COVID-19. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(27), https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1095879

- Baum, F. E., Legge, D. G., Freeman, T., Lawless, A., Labonté, R., & Jolley, G. M. (2013). The potential for multi-disciplinary primary health care services to take action on the social determinants of health: Actions and constraints. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1

- Bitton, A., Fifield, J., Ratcliffe, H., Karlage, A., Wang, H., Veillard, J. H., Schwarz, D., & Hirschhorn, L. R. (2019). Primary healthcare system performance in low income and middle-income countries: a scoping review of the evidence from. BMJ Global Health, 4, e001551. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001551

- Blumenthal, D., Fowler, E. J., Abrams, M., & Collins, S. R. (2020). Covid-19—implications for the health care system. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(15), 1483–1488. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2021088

- Braun, P. A., Quissell, D. O., Henderson, W. G., Bryant, L. L., Gregorich, S. E., George, C., Toledo, N., Cudeii, D., Smith, V., Johs, N., Cheng, J., Rasmussen, M., Cheng, N. F., Santo, W., Batliner, T., Wilson, A., Brega, A., Roan, R., Lind, K., … Albino, J. (2016). A cluster-randomized, community-based, tribally delivered oral health promotion trial in Navajo head start children. Journal of Dental Research, 95(11), 1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516658612

- Business Partnerships Platform. (2020, May 1). Telehealth platform tested in India trialled in Indigenous communities in Australia. Bussiness Partnerships Platform. https://thebpp.com.au/blog/telehealth-platform-developed-in-india-to-be-trialed-in-indigenous-communities-in-australia/.

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, August 10). Influenza (Flu). Past Pandemics. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/basics/past-pandemics.html.

- Charania, N. A., & Tsuji, L. J. (2011). The 2009 H1N1 pandemic response in remote First Nation communities of Subarctic Ontario: Barriers and improvements from a health care services perspective. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 70(5), 564–575. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v70i5.17849

- Charania, N. A., & Tsuji, L. J. (2012). A community-based participatory approach and engagement process creates culturally appropriate and community informed pandemic plans after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: Remote and isolated First Nations communities of sub-arctic Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-268

- Charania, N. A., & Tsuji, L. J. (2013). Assessing the effectiveness and feasibility of implementing mitigation measures for an influenza pandemic in remote and isolated First Nations communities: A qualitative community-based participatory research approach. Rural and Remote Health, 13(4), 2566. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH2566

- Close, R. M., & Stone, M. J. (2020). Contact Tracing for Native Americans in Rural Arizona. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(3). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2023540

- Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, World Health Organization.

- Cousins, B. (2020, October 23). Indigenous mobile health unit combines traditional and modern medicine for treatment. CTVNews. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/indigenous-mobile-health-unit-combines-traditional-and-modern-medicine-for-treatment-1.5157289.

- Crooks, K., Casey, D., & Ward, J. S. (2020). First Nations peoples leading the way in COVID -19 pandemic planning, response and management. Medical Journal of Australia, 213(4), 151. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50704

- Cueva, M., Cueva, K., Dignan, M., Lanier, A., & Kuhnley, R. (2014). Evaluating arts-based cancer education using an internet survey among Alaska community health workers. Journal of Cancer Education, 29(3), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0577-7

- Danila Dilba Health Service. (2020, May 28). Senate Select Committee on COVID-19. Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=b4cd6f4c-b97a-4b91-a5d5-c7bd31ff92f0&subId=684214.

- Davy, C., Harfield, S., McArthur, A., Munn, Z., & Brown, A. (2016). Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: A framework synthesis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0450-5

- Divisions of Family Practice. (n.d.). Virtual Care During COVID-19: Rebuilding Trust and Increasing Access for Katzie First Nation. Divisions of Family Practice. https://divisionsbc.ca/ridge-meadows/blog/katzie-first-nation-virtual-care.

- Dobbins, M. (2017). Rapid review guidebook. National Collaboration Centre for Methods and Tools. https://www.nccmt.ca/uploads/media/media/0001/02/800fe34eaedbad09edf80ad5081b9291acf1c0c2.pdf.

- Draaisma, M. (2021, February 20). Over 8,000 Indigenous people now vaccinated against COVID-19 in Northern Ontario. CBC news. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/operation-remote-immunity-vaccination-update-ontario-indigenous-communities-1.5921847.

- Dreise, H., & Ali, S. (2020, April 15). COVID -19: A practical tool for preparedness and planning in an Indigenous primary care setting in Canada. The College of Family Physicians of Canada. https://www.cfp.ca/news/2020/04/15/04-15-1.

- Driedger, S. M., Cooper, E., Jardine, C., Furgal, C., & Bartlett, J. (2013). Communicating risk to Aboriginal Peoples: First Nations and Metis responses to H1N1 risk messages. PLOS one, 8(8), e71106. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071106

- Dyer, J. (2020). Practicing infection prevention in isolated populations: How Navajo Nation took on COVID-19. Infection Control Today, 24(8), 24–26. https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/how-the-navajo-nation-took-on-covid-19

- Eades, S., Eades, F., McCaullay, D., Nelson, L., Phelan, P., & Stanley, F. (2020). Australia's First Nations’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 396(10246), 237–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31545-2

- Finlay, S., & Wenitong, M. (2020). Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations are taking a leading role in COVID-19 health communication. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 44(4), 251–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13010

- First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). First Nations Virtual Doctor of the Day - How It Works. https://www.fnha.ca/what-we-do/ehealth/virtual-doctor-of-the-day/how-it-works.

- Fitts, M. S., Russell, D., Mathew, S., Liddle, Z., Mulholland, E., Comerford, C., & Wakerman, J. (2020). Remote health service vulnerabilities and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28(6), 613–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12672

- Fitzpatrick, K. M., Wild, T. C., Pritchard, C., Azimi, T., McGee, T., Sperber, J., Albert, L., & Montesanti, S. (2021). Health systems responsiveness in addressing Indigenous residents’ health and mental health needs following the 2016 horse river wildfire in Northern Alberta, Canada: Perspectives from health service providers. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.723613

- Fraser, S., Mackean, T., Grant, J., Hunter, K., Towers, K., & Ivers, R. (2017). Use of telehealth for health care of Indigenous peoples with chronic conditions: A systematic review. Rural and Remote Health, 17(4205). https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4205

- Gampa, V., Smith, C., Muskett, O., King, C., Sehn, H., Malone, J., Curley, C., Brown, C., Begay, M. G., Shin, S., & Nelson, A. K. (2017). Cultural elements underlying the community health representative - client relationship on Navajo Nation. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1956-7

- Goveas, D., Montesanti, S., & Crowshoe, L. (2021, September 30). “It's beyond hesitancy … it’s outright fear”: understanding COVID-19 vaccine Confidence and uptake among Indigenous peoples in Canada. University of Calgary.

- Gray, L., MacDonald, C., Mackie, B., Paton, D., Johnston, D., & Baker, M. G. (2012). Community responses to communication campaigns for influenza A (H1N1): A focus group study. BMC Public Health, 12(205). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-205

- Groom, A. V., Jim, C., LaRoque, M., Mason, C., McLaughlin, J., Neel, L., Powell, T., Weiser, T., & Bryan, R. T. (2009). Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Vulnerable Populations in Tribal Communities. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2008.157453

- Harfield, S. G., Davy, C., McArthur, A., Munn, Z., Brown, A., & Brown, N. (2018). Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: A systematic scoping review. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0332-2

- Henderson, W. (2020, April 20). Province introduces new supports for remote, rural and Indigenous communities during COVID-19 pandemic. The Drive FM. https://www.thedrivefm.ca/2020/04/20/province-introduces-new-supports-for-remote-rural-and-indigenous-communities-during-covid-19-pandemic/.

- Hengel, B., Causer, L., Matthews, S., Smith, K., Andrewartha, K., Badman, S., Spaeth, B., Tangey, A., Cunningham, P., Saha, A., Phillips, E., Ward, J., Watts, C., King, J., Applegate, T., Shephard, M., & Guy, R. (2020). A decentralised point-of-care testing model to address inequities in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 21(7), E183–E190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30859-8

- Herceg, A., Sharp, P. G., Arthur, C. G., & Tongs, J. A. (2010). Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in an urban Aboriginal medical service. Medical Journal of Australia, 192(10), 623–623. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03655.x

- Hernandez, S., Oliveira, J. B., Mendoza Sosof, C., Lawrence, E., & Shirazian, T. (2020). Adapting antenatal care in a rural LMIC during COVID-19: A low literacy checklist to mitigate risk for community health workers. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 151(2), 289–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13332

- Horrill, T., McMillan, D. E., Schultz, A. S., & Thompson, G. (2018). Understanding access to healthcare among Indigenous peoples: A comparative analysis of biomedical and postcolonial perspectives. Nursing Inquiry, 25(3), e12237. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12237

- Hostetter, M., & Klein, S. (2020, September 30). Learning from Pandemic Responses Across Indian country. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/sep/learning-pandemic-responses-across-indian-country.

- International Foundation for Integrated Care. (2020). Realizing the True Value of Integrated Care: Beyond COVID-19. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://integratedcarefoundation.org/publications/realising-the-true-value-of-integrated-care-beyond-covid-19-2#report.

- Jardim, P. de., Dias, I. M., Grande, A. J., O’keeffe, M., Dazzan, P., & Harding, S. (2020). COVID-19 experience among Brasil’s indigenous people. Revista Da Associação Médica Brasileira, 66(7), 861–863. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.7.861

- Jenkins, R., Burke, R. M., Hamilton, J., Fazekas, K., Humeyestewa, D., Kaur, H., Hirschman, J., Honanie, K., Herne, M., Mayer, O., Yatabe, G., & Balajee, S. A. (2020). Notes from the field: Development of an Enhanced Community-Focused COVID-19 Surveillance Program — Hopi Tribe, June‒July 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(44), 1660–1661. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6944a6

- Johnsen, M. (2020, July 17). Why Māori healthcare providers want mobile clinics to become a regular fixture. RNZ. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/421463/why-maori-healthcare-providers-want-mobile-clinics-to-become-a-regular-fixture.

- Jones, T. (2021, February). Rapid service design and cultural safety; Learnings from our General Practitioner Led Respiratory Clinics in Western Nsw. The Health Advocate. https://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjquNPP_YXvAhUPqp4KHecDAh8QFjAYegQIIhAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fahha.asn.au%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2Fdocs%2Fpublications%2Fthe_health_advocate_-_feb_2021_web.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2lv1Rp5_gxUg6TniM5mSdp.

- Kaplan, H. S., Trumble, B. C., Stieglitz, J., Mamany, R. M., Cayuba, M. G., Moye, L. M., Alami, S., Kraft, T., Gutierrez, R. Q., Adrian, J. C., Thompson, R. C., Thomas, G. S., Michalik, D. E., Rodriguez, D. E., & Gurven, M. D. (2020). Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon. The Lancet, 395(10238), 1727–1734. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31104-1

- Kennedy, B. (2020, December 28). Bringing a COVID-19 vaccine to Black and Indigenous communities distrustful of the health system has unique challenges. Here are some places to start. thestar.com. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/12/28/bringing-a-covid-19-vaccine-to-black-and-indigenous-communities-distrustful-of-the-health-system-has-unique-challenges-here-are-some-places-to-start.html.

- Kerrigan, V., Lee, A. M., Ralph, A. P., & Lawton, P. D. (2020). Stay Strong: Aboriginal leaders deliver COVID-19 health messages. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 32(S1), 203–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.364

- Kim, P. J. (2019). Social determinants of health inequities in indigenous Canadians through a life course approach to colonialism and the residential school system. Health Equity, 3(1), 378–381. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2019.0041

- Laupacis, A. (2020). Working together to contain and manage COVID-19. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(13), E340–E341. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200428

- Massey, P., Pearce, G., Taylor, K. A., Orcher, L., Saggers, S., & Durrheim, D. (2009). Reducing the risk of pandemic influenza in Aboriginal communities. Rural and Remote Health, 9, 1290. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH1290

- Massey, P. D., Miller, A., Saggers, S., Durrheim, D. N., Speare, R., Taylor, K., Pearce, G., Odo, T., Broome, J., Judd, J., Kelly, J., Blackley, M., & Clough, A. (2011). Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and the development of pandemic influenza containment strategies: Community voices and community control. Health Policy, 103(2–3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.07.004

- Maxwell, J. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Sage Publications.

- Maybury-Lewis, D. (2002). Indigenous peoples, ethnic groups, and the state. Allyn and Bacon.

- Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications.

- Montesanti, S., & Fayant, B. (2020). Building on Values: Developing an Indigenous Mental Health Response for the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo.

- Montesanti, S., Fitzpatrick, K., Barnabe, C., Robson, H., MacDonald, K., Marchand, T., & Crowshoe, L. (May, 2021). Innovations in Indigenous Primary – Network. Indigenous Primary Healthcare and Policy Research. https://www.iphcpr.ca/publications.

- Moodie, N., Ward, J., Dudgeon, P., Adams, K., Altman, J., Casey, D., Cripps, K., Davis, M., Derry, K., Eades, S., Faulkner, S., Hunt, J., Klein, E., McDonnell, S., Ring, I., Sutherland, S., & Yap, M. (2020). Roadmap to recovery: Reporting on a research taskforce supporting Indigenous responses to COVID-19 in Australia. The Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.133

- Muldoon, L. K., Hogg, W. E., & Levitt, M. (2006). Primary care (PC) and primary health care (PHC). Canadian Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 409–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405354

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools & National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. (2020, October 16). Rapid Review: What factors may help protect Indigenous peoples and communities in Canada and internationally from the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts? Retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/covid-19-rapidevidence-service.

- NCCIH Communications Officer, L. (2016). Pandemic planning in Indigenous communities: Lessons Learned from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in Canada. National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. https://www.nccih.ca/495/Pandemic_planning_in_Indigenous_communities__Lessons_learned_from_the_2009_H1N1_influenza_pandemic_in_Canada.nccih?id=176.

- NSW Health. (2019, July 3). Pandemic preparedness: pandemic planning with Aboriginal communities. Retrieved August 1st, 2021, from https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pandemic/Pages/engaging_aboriginal_communities.aspx.

- Obed, N. (2021). Inuit Governance and Self Determination in Planning and Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. ITK Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiE7_Pyg97vAhWCvJ4KHUMBBswQFjACegQIBxAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ccnsa.ca%2FPublications%2Flists%2FPublications%2FAttachments%2FVS%2FNatan%2520Obed%2520-%2520NCCIH%2520Virtual%2520Series%2520-January%252013%25202021%2520(PDF).pdf&usg=AOvVaw276zrE5X2Uhenqntbdbk0_.

- OCHA. (2020, November 6). Colombia responds to COVID-19 with an intercultural health model. World Health Organization. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://reliefweb.int/report/colombia/colombia-responds-covid-19-intercultural-health-model.

- O'Keefe, V. M., Cwik, M. F., Haroz, E. E., & Barlow, A. (2021). Increasing culturally responsive care and mental health equity with indigenous community mental health workers. Psychological Services, 18(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000358

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- PHCPI. (2018). Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://improvingphc.org/key-messages-covid-19-and-primary-health-care.

- Pinto, A. D., & Bloch, G. (2017). Framework for building primary care capacity to address the social determinants of health. Canadian Family Physician, 63(11), e476–e482.

- Rasanathan, K., Montesinos, E. V., Matheson, D., Etienne, C., & Evans, T. (2011). Primary health care and the social determinants of health: Essential and complementary approaches for reducing inequities in health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65(8), 656–660. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.093914

- Rawaf, S., Allen, L. N., Stigler, F. L., Kringos, D., Quezada Yamamoto, H., & van Weel, C. (2020). Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. European Journal of General Practice, 26(1), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2020.1820479

- Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health (pp. 1–47). National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

- Richardson, K. L., Driedger, M. S., Pizzi, N. J., Wu, J., & Moghadas, S. M. (2012). Indigenous populations health protection: A Canadian perspective. BMC Public Health, 12(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1098

- Richardson, L., & Crawford, A. (2020). COVID-19 and the decolonization of INDIGENOUS public health. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(38), https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200852

- Roberts, L. (2020, May 03). Aboriginal Territorians are ‘significantly represented’ in disease outbreaks, but not coronavirus. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-04/coronavirus-nt-aboriginal-outcomes-show-lessons-for-future/12188762.

- Rosenthal, E. L., Menking, P., & Begay, M.-G. (2020). Fighting the COVID-19 Merciless monster. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 43(4), 301–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/jac.0000000000000354

- Rudge, S., & Massey, P. D. (2010). Responding to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in Aboriginal communities in NSW through collaboration between NSW Health and the Aboriginal community-controlled health sector. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin, 21(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.1071/nb09040

- Saskatchewan Health Authority. (2021a). Working together to support immunization. Saskatchewan Health Authority. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.saskhealthauthority.ca/news/stories/Pages/2021/March/Working-together-to-support-immunization.aspx.

- Saskatchewan Health Authority. (2021b). Mobile COVID-19 testing meeting community at points of need. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.saskhealthauthority.ca/news/stories/Pages/2021/February/Mobile-COVID-19-testing-community.aspx.

- Schneider, H., Hlophe, H., & van Rensburg, D. (2008). Community health workers and the response to HIV/AIDS in South Africa: Tensions and prospects. Health Policy and Planning, 23(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czn006

- Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

- United Nations. (n.d.). Indigenous people. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/about-us.html.

- United Nations (General Assembly). (2007). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.

- Valentijn, P. P., Schepman, S. M., Opheij, W., & Bruijnzeels, M. A. (2013). Understanding integrated care: A comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 13(1), e010. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.886

- Van den Broucke, S. (2020). Why health promotion matters to the COVID-19 pandemic, and vice versa. Health Promotion International, 35(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa042

- van Weel, C., & Kidd, M. R. (2018). Why strengthening primary health care is essential to achieving universal health coverage. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(15), E463–E466. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170784

- Watt, A., Cameron, A., Sturm, L., Lathlean, T., Babidge, W., Blamey, S., Facey, K., Hailey, D., Norderhaug, I., & Maddern, G. (2008). Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: An inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 24(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462308080185

- WCH Indigenous Health. (n.d.). Maad'ookiing Mshkiki - Sharing Medicine. Women's College Hospital. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.womenscollegehospital.ca/research,-education-and-innovation/maadookiing-mshkiki%E2%80%94sharing-medicine.

- World Health Organization. (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata. Retrieved January 1, 2021, from http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2008). The world health report 2008: Primary health care now more than ever. World Health Organization, 1–148. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43949.

- World Health Organization Europe. (n.d.). Past pandemics. Retrieved on December 3, 2021 from https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/pandemic-influenza

- Wright, M., & Mainous III, A. G. (2018). Can continuity of care in primary care be sustained in the modern health system? Australian Journal of General Practice, 47(10), 667–669. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-06-18-4618