ABSTRACT

Since 2015 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been supporting the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Tonkolili district, Sierra Leone, with an integrated health care approach at the community, primary health centre (PHC), and hospital level. This programme is planned to be handed over to MoH. To prepare for this handover, a qualitative study exploring elements of a successful handover was undertaken in 2019. Focus group discussions (FGD) with the community members (n-48) and in-depth interviews (IDI) with MSF staff, community leaders, and MoH staff in Sierra Leone (n-15) were conducted. Data were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim from English, Creole, and Themne, coded, and thematically analysed. Participants expressed that an optimal project handover and exit strategy should be a continuous, long-term, the staggered process included from the inception of the programme design. It requires clear communication and relationship building by all relevant stakeholders and demands efficient resources and management capacity. Associated policy implications are applicable across humanitarian settings on the handover of programmes where the government is functional and willing to accept responsibilities.

Introduction

The handover of medical or humanitarian services is a process of passing responsibility for activities from one actor to another, including humanitarian groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the local community, or the Ministry of Health (MoH). Whilst Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is operational in several humanitarian contexts which require handover to longer-term providers regularly, there is no standard exit strategy across projects (Gerstenhaber, Citation2014).

Furthermore, there are limited published studies, which explore handing over medical or humanitarian services managed by international organisations in lower and middle-income countries (LMIC). Available literature focuses on sustainability as a key aspect of handover of programmes (Cairney & Kapilashrami, Citation2014; de Gruchy & Kapilashrami, Citation2019; Humphries et al., Citation2011; Shediac-Rizkallah & Bone, Citation1998). Internal guidance has been developed through evaluation reports and lessons learned to help MSF orientate the process to ensure continuity of quality of care after handing over (MSF, Citation2007).

Most exit strategies are built with the specific intention of handing over activities within a defined period, utilising a process-oriented approach, with clearly defined objectives that reflect the context reality (Pett, Citation2011). There is some consensus from programme evaluations that consideration of eventual handover should be made from the beginning of the programme to allow for project activities to function constructively (Désilets, Citation2010; Gerard Verbeek, Citation2014; Gerstenhaber, Citation2014; Marielle Bemelmans, Citation2016). Handovers need to allow for relevant adjustments and reflect on post-handover experiences to elicit lessons learned and promote accountability (Désilets, Citation2010; Gerard Verbeek, Citation2014; Marielle Bemelmans, Citation2016). At handover, the goal should be a programme with the greatest impact on the population with regards to the service availability, quality of service, and level of accessibility after departure (Pett, Citation2011). Finally, it is recognised that planning and implementing a successful handover involves a high degree of cooperation with other actors from the start (MSF, Citation2007), though this is not always realised.

Since 2015 MSF has been supporting the MoH in Sierra Leone, providing medical care at Magburaka Provincial Hospital and rural primary health centres (PHC) in the Tonkolili district. MSF's main operational objective there is to reduce maternal and child mortality through a comprehensive and integrated health care approach at the community, PHC, and hospital levels, with services, provided free of charge. In 2009, Sierra Leone's under-five child mortality rate (<5 CMR) was the highest in the world, at 168 deaths per 1000 live births (UNICEF, Citation2020) leading the government in 2010 to implement the Free Health Care Initiative (FHCI) abolishing user fees for pregnant and lactating women, and children under five years of age (Witter et al., Citation2018). By 2019 the <5 CMR had fallen to 109 deaths per 1000 live births but remained the fifth highest in the world (UNICEF, Citation2020). In 2013 the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was estimated the world’s highest at 1165 deaths per 100,000 live births according to district health survey data. In 2015 the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated MMR of 1360 deaths per 100,000 live births (WHO, Citation2015). Sierra Leone remains a country in need of improved access to health services, provision of quality health services, equity in health services, promotion of efficiency of service delivery, and inclusiveness (UNICEF, Citation2014). The country's health system was battered by the impact of Ebola when the health system was severely compromised due to overwhelming demand, healthcare workers’ deaths, resource diversion, and closure of health facilities that resulted in increased morbidity and mortality (Elston et al., Citation2017).

This study was designed to further the knowledge generated through previous handover evaluations conducted in Kenya, Mozambique, and Lesotho (Désilets, Citation2010; Gerard Verbeek, Citation2014; Marielle Bemelmans, Citation2016), and build on internal MSF guidance. In addition, this study was conducted to operationalise the contextual approach for Sierra Leone looking at how MSF can improve activities, based on timelines, resources, and attention needed for a successful handover. MSF plans to handover their medical programming in Tonkolili to MoH once objectives on improved maternal and child mortality are reached, in an estimated, three to four years. To prepare for this handover, an exploration of perspectives of MSF, MoH, health workers and the local communities was undertaken. This qualitative study aimed to provide an insight on how a humanitarian actor should prepare for and implement the process of handing over medical activities to the MoH in the Tonkolili district in Sierra Leone.

Methods

Study design

This study used a qualitative design with an exploratory approach. Data was gathered between October and November 2019, using in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) to understand the different perspectives of participants.

Study setting

Sierra Leone is divided into 14 districts in which the MoH is the major health care provider in addition to available private clinics and hospitals. Community Health Centres (CHC) function at chiefdom headquarters towns (urban) and Community Health Posts (CHP) and Maternal and Child Health Posts (MCHP) in villages (rural) within the chiefdoms. Each district headquarters town has a district hospital and tertiary level of care is provided at regional headquarters towns (Leone, Citation2014). In the Tonkolili district, MSF provides health services in seven to nine locations out of 106 health facilities (Research, Citation2017). The CHP and MCHP treat and manage patients and make referrals to the CHC. The study took place in two CHP, two CHC and one hospital where MSF supports maternal and child health care. The communities where this study took place had previous experience with MSF handing over to MoH in 2007.

Study populations

IDIs were conducted with a range of profiles, including MoH policymakers at the central government and district level, MSF staff, and community leaders. FGDs were conducted among community members.

Purposive sampling was used to identify eligible MSF and MoH healthcare providers, policymakers, and strategic decision-makers. MSF and MoH staff were selected at the health facilities where MSF is providing medical services and the policymakers were selected at the district and provincial levels. Their choice was based on their ability to provide in-depth and detailed operational and policy level information in Maternal and Child Health (MCH) programmes where MSF worked.

Convenience sampling was used to identify community members and community leaders eligible to participate in FGDs and IDIs respectively. To facilitate open sharing, FGDs were separated by gender to allow opinions from both sides equally heard. At the community level, IDIs and FGDs were conducted only where MSF had a physical presence through service provision in existing MoH facilities. Community leaders were chosen based on their seniority and availability whilst the FGDs allowed the gender aspect to be balanced.

Data collection

Permission was requested at the district level through the District Medical Officer (DMO) to reach study participants in the district. A courtesy call to the chief in the chiefdom was also made before data collection took place. Study participants provided informed consent to be interviewed and audio recorded.

Based on the researcher's team experience in previous qualitative studies, the number of participants in IDIs and FGDs was predefined. However, during the interviews even when saturation was reached, data collection was never stopped early.

Taking into account that the research team were predominantly MSF staff, issues regarding bias were considered. The social desirability bias was managed by having an external non-MSF person for data collection at the district and community levels. As well, clear explanations of the purpose of the study and the need for honest feedback was emphasised in meetings before the study started and was reflected in the consent forms. Confirmation bias was managed by making sure proper coding and thematic analysis was done by three researchers. Observation bias was addressed by increasing the methods of data collection and variation of study participants to allow wider triangulation of data.

The Principle Investigator (PI), who belonged to MSF, conducted the IDIs with policymakers and MSF staff with the research assistant, who was non-MSF, but was hired specifically for the study. The research assistant conducted the IDIs for MoH staff at the health facility level and in the community for community members and community leaders. The research assistant conducted all FGDs and IDIs in Themne and/or Creole, two of the most common languages of the region. For Themne, a direct translation took place during the FGDs or IDIs to enhance discussion with the research assistant. The PI transcribed all the audio recordings with MoH policymakers and MSF staff; the research assistant transcribed all FGDs and IDIs.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis (Gibbs, Citation2007) was conducted manually to examine and interpret the qualitative data. The findings from the transcripts were labelled and organised to identify different themes and relationships. A six-step process was used which included familiarisation, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes. Data were first examined individually by MSF staff, MoH staff, and the community perspective to identify common themes and compare the themes across groups. This approach recognised that each group was unique and would be affected by the handover differently. The comparison of themes also helped to identify common aspects that would be transferable to other handover processes in other contexts. Data analysis was conducted by the PI, and a subset of transcripts were analysed by three other members of the research team with experience in qualitative data analysis, to enhance the quality and reliability of findings.

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants before the IDI and or FGD recordings. The study protocol was approved by both the MSF Ethics Review Board (reference 1924) and the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee.

Results

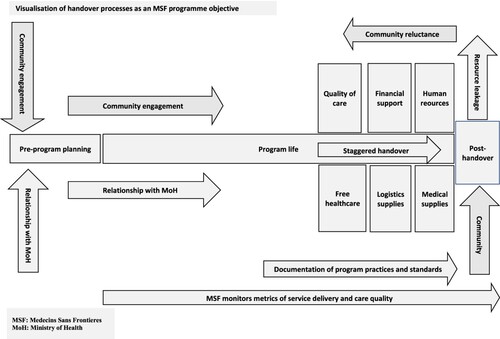

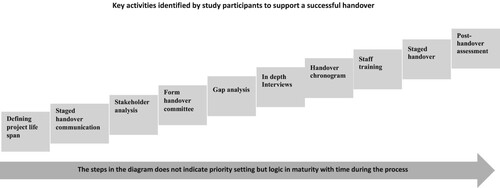

A total of 35 IDIs and four FGDs were conducted and shows their social and demographic characteristics. Analysis of data revealed three key themes. First, project handovers and exit strategies should be viewed as a continuous, longer-term process from the start of a programme. Built into this process are the remaining two intersecting themes: (1) clear communication and relationship building and (2) efficient resourcing and management. Ultimately, the success or failure to execute this process can affect the package of care post-handover and exit from the project. These three themes are presented in further detail below in with additional visualisation of data analysis to complement the narrative in .

Table 1. Social demographic information of study participants enrolled in in-depth interviews or focus group discussions.

Table 2. Study recommendations and feasibility requirements.

Handover as a continuous longer-term process

There was consensus among study participants that project handover should be considered at the beginning of project design and from the inception of project activities. This step was vital to facilitate early reflection on what activities the partner could feasibly take on after handover. Several participants suggested that once a project was running, MSF should include moments of reflection and engagement, as well as regular check-ins, with key stakeholders to understand the progress of the programme and allow adjustments throughout the project life span.

… [At] the start of the project you should start thinking of the handover … [if] tomorrow or sometime [later] I will be exiting, … [is]this … something I want to start today [that] could continue with the MoH. (In-depth interview with MSF staff_4)

I think the best time [to reflect] should not be at the end, [but] during implementation [when] you should be thinking of … [areas] to identify some of the weakness, … [during], implementation [start] thinking of what you need to put in place before handing over before it is too late. (In-depth interviews with MoH staff Freetown_3)

It was proposed by one study participant that a handover should be ‘ … an objective in itself … ’ (IDIs with MSF staff Amsterdam_1). This was complemented by additional MoH and MSF study participants who suggested that the day-to-day activities of the project should be measured to ensure and evaluate timelines and success both before and after the handover. An example ‘After the handing over, we are also expecting MSF to … monitor the process’. (IDI with MoH staff Freetown_7). : Visualisation of the handover process as an MSF programme objective from pre-planning to post-handover phase gives more details.

Clear communication and relationship building

Communication about the handover and planned timeframe were widely considered by study participants as vital. Different stakeholders highlighted varying modes and purposes of such communication. MSF and MoH stakeholders emphasised communication around planning regarding timelines and budgeting.

Communication, communication and communication. That it is really clear about why you handover on the proposed time frame [and] leaving enough space for feedback. [P]referably not [to] dictate the time frame fully from MSF side and therefore be ready to adjust … . [MoH] budgetary years or timeframes are different to ours … [MSF should] continue throughout the process with communication to eliminate barriers which come along as the handover progresses. (IDI with MSF staff_1)

… as you prepare to handover, take into consideration that there should be collective interaction between you and other stakeholders. Their involvement, their ideas, their input are very relevant because, at the end of the day, they are all going to contribute to ensuring that what you are doing is sustainable and will continue. (IDI with MoH staff Freetown_7)

… create a relationship with key parts of MoH that goes beyond contractual memorandum of understanding (MoU) level to actually build a relationship that resembles something of trust and transparency from both sides … (IDI MSF staff_2)

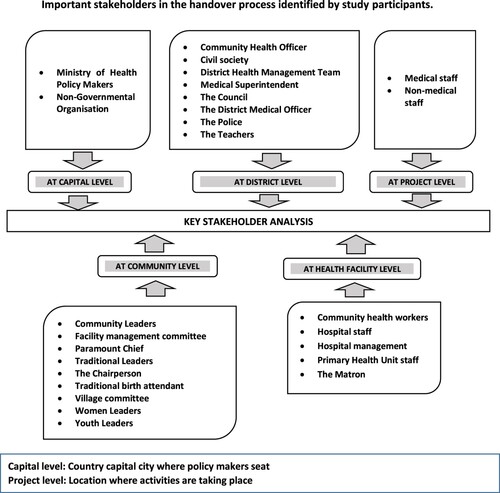

You need to involve … different stakeholders to be part of the exit procedures, so I think starting from the national level … the district level … the hospital level … and [the] community stakeholders should be part of the process. (IDI MoH staff Freetown_3)

Efficient resourcing and management

The importance of dedicated resourcing was a recurrent need for successful handovers. This included appropriately trained human resources, adequate medical supplies, and financing to specific facilities before, during, and after handover. Both community and MoH participants shared their experiences that following previous MSF exits, instances of ‘medical machines being sold’ or ‘disappearing’ from the facility were common. Concerns were raised that this would happen again, with mechanisms proposed to avoid such events. A suggestion from several participants was to make sure there was a clear process of documenting and planning for assets to be handed over.

… the hospital has first enough human resources, continuation or uninterrupted supply at least at the base level, these two are key [handover elements] … (IDI MSF staff Tonkolili_3)

You will leave drugs there people will take away, you will leave vehicles people may want to not mention, we know all about that … [it] is so important that the documentation mentions what is left [after handover]. (IDI MoH staff_5)

Looking at the [mothers] and the under-fives, they are having free treatment; now MSF is about to fold up, we want them to put a mechanism in place to the government so that our mothers and children may have continued free medical facilities, [no] sooner MSF folds up, the price will increase for them and most of them … that [money they] would not have. (FGD participant Tonkolili_4)

This is the community that has participated in the free health care services for the under-fives by government policy; however, MSF and the Magburaka government hospital goes extra mile to providing from zero to fifteen years of age … [To] me that is the significant challenge the community is going to face when MSF push off … (IDI MoH staff Freetown_7)

MSF should leave the vehicles, [and] the ambulances, … (I)f they leave these cars for them then they will be … . [the] same services as MSF … [on] timely referrals. (FGD participant Tonkolili_4)

Whatever the supply chain mechanism you are using right now, should be embedded in the general MoH supply chain system … The] bottom line is if you train your staff very well they will be able to manage their stock levels … (IDI MoH staff Freetown_4)

MSF treated them with care and respect[ed] their dignity before now their dignity was low, [and] they were not respected in taking medical service. (FGD participant Tonkolili_12)

Discussion

The study revealed that a handover can be successful when considered as a process that starts from the inception phase of the programme and continues until after MSF had exited. Communication and collaboration with key stakeholders were highlighted as important. In addition, sufficient allocation of resources, including finances, human resources and materials, were core components to ensure both the quality and sustainability of services post-handover.

Quality and sustainability of services

Through an exploration of community perspectives, this study exposed the fears of deteriorating quality and sustainability of services once MSF departed. Specifically mentioned were concerns about staff attitudes in health facilities and the lack of accountability for resources including the implementation of the free health care initiative. Several solutions were proposed. First, a ‘gap analysis’ should occur to identify challenges to maintain programmes implemented outside the scope of what the MoH normally provides. Training of staff to ensure improved patient-provider communications was identified as a second critical component. Finally, good quality handover reporting, including an inventory of resources, would facilitate post-handover evaluation. The importance of robust documentation and reporting during the handover has been previously recognised (Gerstenhaber, Citation2014; Hunt et al., Citation2020; Pett, Citation2011). Post-handover evaluation is seen as optional and not an essential activity (Gerstenhaber, Citation2014; Pett, Citation2011) but can enable an understanding of the impact of the handover (GBV, Citation2018; Hunt et al., Citation2020; Pal et al., Citation2019).

Contrary to this last study, we interpret that post-handover evaluations should be considered as essential rather than an optional component of handover processes. Critically, they provide a key mechanism to monitor the quality and sustainability of services and ensure longer-term access for communities. Our study identified management processes adopted during the scale-up which later proved sustainable in the context of scale down (Cairney & Kapilashrami, Citation2014). Other studies are in line with these findings with a more concrete look at sustainability through factors such as programme design and implementation, organisation of settings and community environment (Shediac-Rizkallah & Bone, Citation1998). Regarding the FHCI, other papers have reflected the fear expressed by the community of increased financial burden following the withdrawal of external funds since the most common strategy by MoH is to increase client fees (Shediac-Rizkallah & Bone, Citation1998). However, careful planning by donors and grantees, setting realistic fees, seeking alternative sources of funding and diversification of services could mitigate the financial impact (Shediac-Rizkallah & Bone, Citation1998).

Communication and collaboration with stakeholders

An early stakeholder analysis was identified by this study as critical for the identification of who should be involved in objective settings and programme design. The value of having a range of perspectives from programme implementers, policymakers, and the community would enhance the handover process and quality of services. The inclusion of voices of all relevant stakeholders in a transition process (Pal et al., Citation2019), as well as in programme design should be included from the beginning (GBV, Citation2018), as has been previously documented. Some literature has suggested the use of assessments to monitor challenges in partnership with stakeholders (Tull, Citation2020). This study proposes additional options for improving collaboration with stakeholders, such as communicating timelines and the steps of project handover and building in moments of reflection to adapt the programme to new realities. These findings are supported by (de Gruchy & Kapilashrami, Citation2019) specifically on the time needed to prepare for handover, and the progressive reduction of services (Cairney & Kapilashrami, Citation2014). Consistency of messages on handover (Pal et al., Citation2019), transparency (Pett, Citation2011) and planning (Gerstenhaber, Citation2014) support our findings.

Handover as an objective

Important in this study is the need to have handover as an objective in itself. This outcome is different from what is currently described in the literature suggesting having a handover strategy with specific objectives (Gerstenhaber, Citation2014; Pal et al., Citation2019; Pett, Citation2011). This study outlined a staged handover approach to allow gradual adaptation by the MoH or whoever is taking over responsibilities, which is a novel finding compared to previous literature regarding comprehensive care programmes. It can be closely associated with what is mentioned in other papers as a gradual adaptable process or progressive reduction (de Gruchy & Kapilashrami, Citation2019; Pal et al., Citation2019; Pett, Citation2011; Tull, Citation2020). This approach seems to be standard in vertical programmes such as HIV where patients and activities can be handed over in a stepwise approach (MSF, Citation2007). The importance of starting to plan a handover from the beginning aligns with existing literature (GBV, Citation2018; Gerstenhaber, Citation2014; Hunt et al., Citation2020; MSF, Citation2007; Pal et al., Citation2019; Tull, Citation2020). Our findings support the identification and engagement of key stakeholders, such as MoH and the community from the start of the programme. This is further supported by existing literature (Désilets, Citation2010; GBV, Citation2018; Pal et al., Citation2019; Pett, Citation2011; Tull, Citation2020) though it is not clear when engagement should happen.

Study implications on policy and practice

The concerns regarding the continuity of FHCI need further exploration specifically by the MoH. Currently, post-handover evaluations are designated as optional by MSF and are not routinely conducted. This situation should be revisited in light of our findings. A review of agreements signed between MoHs and NGOs should consider the inclusion of handover as a commitment for the services planned in the country. To maintain integrity, increased transparency regarding disposal of assets and emphasis on staff training regarding patient interaction need to be added to the package of handover preparation.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the inclusion of community voices, marking a departure from previous studies which have predominantly relied on provider perspectives. Given previous handovers by MSF to other partners, study participants such as the community were familiar with handover programmes, thereby offering a greater depth of perspective on the topic.

Whilst the findings of this study are largely applicable across humanitarian settings, this study was focused on a context where functional and stable government architecture is in place to accept responsibility for a health programme handover. Other settings where handover occurs from one NGO to another, or where security, financial, cultural or programmatic components differ from those here may need to consider slightly different principles. In this respect, the findings of this study may not be generalisable to such situations, which warrants additional research.

A limitation is that the study team was largely made up of MSF members of the Operational Research Units in Luxembourg and Amsterdam. Only a few study personnel were outside MSF; two were an MoH staff member of the Directorate of the Health System, Policy, and Planning and the research assistant. These affiliations may have impacted the study with social desirability bias.

Conclusion

Our findings from Sierra Leone suggest the value of having guidelines for programme handover for MSF and other humanitarian organisations. These include making the handover an objective from the outset, staged communication with all stakeholders including MoH and community leaders, creating a handover committee, performing ‘gap analysis’, developing a handover chronogram, planning a staged handover and concluding with a post-handover assessment. Using these principles, a handover plan could be adapted to a particular context, ensuring a successful transition of patient care.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organisation (WHO/TDR). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF/Doctors Without Borders). The specific SORT IT programme which resulted in this publication was developed and implemented by MSF. The authors would like to thank the study participants for sharing their invaluable perceptions and perspectives. In particular, the MoH and the MSF team in Sierra Leone for their collaboration and support. Thanks to Bilal Ahmad for facilitating ethics review approval in Sierra Leone and Rhian Gastineau for facilitating conversations with MoH policymakers. NS conceived the study, NS and EA designed the study, NS and JF conducted data collection, NS, KW and EB analysed data, NS, EB, KW, CW discussed the analysis and structure of the manuscript, NS drafted the manuscript with support from EB, KW, and CW. NS, EB, KW, CW, KK and FS reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. TR supported with editing. All Authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cairney, L.I, & Kapilashrami, A. (2014). Confronting ‘scale-down’: Assessing Namibia’s human resource strategies in the context of decreased HIV/AIDS funding. Global Public Health, 9(1-2), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.881525

- de Gruchy, T., & Kapilashrami, A. (2019). After the handover: Exploring MSF’s role in the provision of health care to migrant farmworkers in Musina, South Africa. Global Public Health, 14(10), 1401–1413. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1586976

- Désilets, A. (2010). Lesotho handover: Assessment of handover strategy of MSF B HIV/TB programme [Evaluation report]. M. E. Unit. https://evaluation.msf.org/evaluation-report/lesotho-handover-assessment-of-handover-strategy-of-msf-b-hivtb-programme

- Elston, J. W. T., Cartwright, C., Ndumbi, P., & Wright, J. (2017). The health impact of the 2014–15 Ebola outbreak. Public Health, 143, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.020

- GBV. (2018). Guidance note on ethical closure of GBV programmes: GBV SC whole of Syria -Turkey/Jordan Hub – Sep 2018 [Policy paper]. OCHA. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/stima/document/guidance-noteethical-closure-gbv-programsenar

- Gerard Verbeek. (2014). Evaluation of handover: Strategic implementation in two minds, Report of the handover process and replicability of handover tool in Maputo Project, Mozambique Mission [Evaluation Report]. M. E. Unit. http://evaluation.msf.org/evaluation-report/evaluation-handover-strategy-implementation-two-minds-report-handover-process-and

- Gerstenhaber, R. (2014). 2014 handover toolkit 2.0, “Success Is Also Measured By What You Leave Behind” [Policy paper]. evaluation.msg.org. https://evaluation.msf.org/sites/evaluation/files/handover_toolkit.pdf

- Gibbs, G. R. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. In U. Flick (Ed.), Analysing qualitative data. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208574

- Humphries, D., Gomez, L., & Hartwig, K. (2011). Sustainability of NGO capacity building in Southern Africa: Successes and opportunities. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 26(2), e85–e101. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.1029

- Hunt, M., Eckenwiler, L., Hyppolite, S.R., Pringle, J., Pal, N., & Chung, R. (2020). Closing well: National and international humanitarian workers’ perspectives on the ethics of closing humanitarian health projects. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 5(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-020-00082-4

- Leone, S. S. (2014). Sierra Leone, demographic health survey. MEASURE DHS ICF International Rockville, MD USA. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR42/PR42.pdf

- Marielle Bemelmans, A. D. (2016). Evaluation of Homa Bay Handover MSF OCP Kenya [Evaluation report]. V. E. Unit. http://evaluation.msf.org/sites/evaluation/files/attachments/evaluation_of_homa_bay_handover_kenya_jan_2016_en.pdf

- MSF. (2007). HIV AIDS programmes in resources limited settings: Handover and exit strategies, Approaches and recommendations for MSF programmes [Policy paper].

- Pal, N. E., Eckenwiler, L., Hyppolite, S.R., Pringle, J., Chung, R., & Hunt, M. (2019). Ethical considerations for closing humanitarian projects: A scoping review. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 4(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-019-0064-9

- Pett, L. (2011). Making an exit: Advice on successful handover of MSF programmes [Anthropology report]. M. UK. http://evaluation.msf.org/evaluation-report/making-and-exit-advice-on-successful-handover-of-msf-projects

- Research, J. (2017). Advancing partners and communities, Sierra Leone strengthening reproductive, maternal newborn and child health services as part of the Ebola transition (District Summary, Issue). WWW.ADVANCINGPARTNER.ORG

- Shediac-Rizkallah, M. C., & Bone, L. R. (1998). Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: Conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Education Research, 13(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/13.1.87

- Tull, K. (2020). Responsible exit from humanitarian interventions [K4D Helpdesk Report]. https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/responsible-exit-from-humanitarian-interventions#citation

- UNICEF. (2014). Sierra Leone Health Facility Survey 2014, Assessing the impact of the EVD outbreak on health systems in Sierra Leone [Survey].

- UNICEF. (2020). UNICEF Child Mortality Estimates [Statistics]. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/under-five-mortality/#:~:text=The%20global%20under%2Dfive%20mortality%20rate%20declined%20by%2059%20per,1990%20to%2038%20in%202019

- WHO. (2015). Maternal mortality in Sierra Leone. WHO. https://www.afro.who.int/countries/sierra-leone

- Witter, S., Brikci, N., Harris, T., Williams, R., Keen, S., Mujica, A., Jones, A., Murray-Zmijewski, A., Bale, B., Leigh, B., & Renner, A. (2018). The free healthcare initiative in Sierra Leone: Evaluating a health system reform, 2010–2015. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 33(2), 434–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2484