ABSTRACT

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major public health issue in Papua New Guinea, with incidence rates particularly high in the South Fly District of Western Province. We present three case studies, along with additional vignettes, that were derived from interviews and focus groups carried out between July 2019 and July 2020 of people living in rural areas of the remote South Fly District depicting their challenges accessing timely TB diagnosis and care; most services within the district are only offered offshore on Daru Island. The findings detail that rather than ‘patient delay’ attributed to poor health seeking behaviours and inadequate knowledge of TB symptoms, many people were actively trying to navigate structural barriers hindering access to and utilisation of limited local TB services. The findings highlight a fragile and fragmented health system, a lack of attention given to primary health services, and undue financial burdens placed on people living in rural and remote areas associated with costly transportation to access functioning health services. We conclude that a person-centred and effective decentralised model of TB care as outlined in health policies is imperative for equitable access to essential health care services in Papua New Guinea.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading infectious cause of death globally, with 1.5 million people dying from the disease in 2020 (WHO, Citation2021b). TB is both a preventable and curable infectious disease and continues to be a serious public health problem primarily for the most vulnerable and impoverished populations in low to middle income countries. People with TB need to be treated and diagnosed as early as possible to reduce community transmission of disease and risk of severe illness and death. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global COVID-19 pandemic has had an adverse effect on TB, reversing the progress seen in previous years (WHO, Citation2021a, p. 1). In 2020 there was a significant reduction in the number of people worldwide diagnosed and reported with TB resulting in a global increase of annual TB deaths for the first time in decades.

The WHO End TB Strategy advocates (WHO, Citation2014, p. 7) for countries to prioritise universal access to early diagnosis and rapid initiation of effective treatment ‘to ensure provision of high-quality, integrated, patient-centered tuberculosis care and prevention across the health system.’ This is not so easily realised in countries with weak health systems, with significant rural and remote populations, and where people have limited access to primary health services or experience delays in healthcare seeking (Storla et al., Citation2008).

Papua New Guinea, the largest country in the Pacific, has a high prevalence of TB, multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) and HIV and TB infection (WHO, Citation2021a). The programmatic delivery of TB care is challenging as the majority of the 8.8 million population (World Bank, Citation2020) live in rural and remote areas, be they islands or mountainous terrain, lack access to roads, and have limited to no access to primary health care services (Cairns et al., Citation2018). It is widely recognised that many health centres and community health posts in remote and rural areas of the country are not open, rundown and experience medicine shortages, and lack the qualified health professionals to deliver services (M. Macintyre, Citation2019). As a result, many people in these areas are prevented from or experience delays in accessing specialised services that are only offered in urban and provincial capitals. This results in urban residents having ‘better access and much higher outpatient contacts’ than their rural and remote counterparts (Grundy et al., Citation2019, p. xxi), despite the national health plan being designed both for the rural and remote majority and urban disadvantaged (PNG National Department of Health, Citation2010). Papua New Guinea’s decentralised health system is undergoing reforms to improve health service delivery. The ‘weak’ health system still results in ‘delays in TB diagnosis (…) and influences health seeking behaviours including utilisation of health services’ (Specialist Health Service, Citation2019, p. 2). Additionally, high rates of loss from TB care have also been documented (Aia et al., Citation2018).

In this article we present case studies and vignettes to illustrate the realities of accessing timely TB diagnostic and treatment services for and by people living in the rural and remote South Fly District of Papua New Guinea. The South Fly District is a known ‘hotspot’ for TB and MDR-TB (Morris et al., Citation2019). As part of a wider qualitative study that aimed to examine the socio-cultural dimensions of TB control in Papua New Guinea, we concern ourselves with understanding the structural cause of delays to timely TB diagnostics and treatment; delays related to the policy and health system environment. In doing so, we highlight the importance of moving beyond reinforcing patient delays that focus on individual behaviour change, and critically examine and address the structural impediments bought about by the current model of primary health care being implemented in Papua New Guinea.

Background

Delays to TB diagnosis and treatment

The public health research on TB diagnosis and treatment delays, including a number of systematic reviews, is substantial and typically focuses on the extent or number of days delayed, and factors behind the delay (see for example, Bello et al., Citation2019; Sreeramareddy et al., Citation2009). Most studies classify ‘delay’ as either related to the patient or the health system (or sometimes ‘health provider’). The number of days between onset of symptoms to first contact with a health provider is considered a period of ‘patient delay’, and the subsequent period between the patient’s first point of contact with a health provider to onset of TB treatment is considered a period of ‘health system delay,’ with some studies breaking this down further to include diagnosis or treatment delay period (Cai et al., Citation2015; Makwakwa et al., Citation2014; WHO, Citation2006). Factors related to a delay in TB diagnosis and treatment varies by setting, but themes typically identified that influence the patient delay period include not recognising the signs and symptoms of TB, personal attitudes and beliefs, socio-economic status, using traditional medicine or traditional healers, stigma, and limited access to health services due to geographic location (Storla et al., Citation2008; Teo et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, health system delays are influenced by staff shortages, lack of health infrastructure, cost of services, types of services on offer (e.g. a lack of TB diagnostics), and unavailability of TB medication (Cai et al., Citation2015; Oga-Omenka et al., Citation2021; Teo et al., Citation2021).

The literature related to patient delays often focuses on the patients’ health-seeking behaviours, with many studies including recommendations targeting the individual. Such interventions include improving people’s knowledge of the signs and symptoms of TB (Lambert & Van der Stuyft, Citation2005). For those concerned with the wider structural factors that influence health outcomes, such as those produced as a result of the policy, health system and/or economic environments, this narrow focus on individuals – patient delays – risks portioning blame on the person with TB and being ‘biased towards patients’ factors’ (Lambert & Van der Stuyft, Citation2005, p. 946), rather than addressing systematic failures that are out of a person’s control, but which nevertheless impact negatively on their health. When undertaking a review on literature related to TB treatment delays, Lambert and Van der Stuyft (Citation2005, p. 945) suggest that many studies tended to put more weight on patient factors, ‘even when the data suggest otherwise.’ In most TB endemic countries, there is already a high burden placed on people with TB to access care. In these settings, people with TB are the ones responsible for presenting at a health service in the first instance in what is called a ‘passive case finding approach’ (Ho et al., Citation2016, p. 375). This ‘patient-initiated’ approach is different from ‘active tuberculosis case finding’ ‘which is the systematic identification of people with suspected (presumptive) active TB, in a predetermined target group, using tests, examinations or other procedures that can be applied rapidly (WHO, Citation2015, p. 2).’ It is assumed within the passive case finding approachFootnote1 that the person seeking treatment recognises that their symptoms are serious enough to warrant a visit to a health care provider, have access to health services, and for the health provider to subsequently diagnose TB (Ho et al., Citation2016). This approach puts significant onus on the person seeking treatment who needs to find the ways and means to access services that are often not easily accessible and/or may come at a significant financial cost. This becomes even more challenging for those living in rural and remote settings, as there is evidence that shows people with TB experience longer patient delay due to a lack of TB services in these areas, resulting in the need for targeted and new outreach approaches (Teo et al., Citation2021), such as active case finding (Honjepari et al., Citation2019).

Health systems and TB in Papua New Guinea

In Papua New Guinea’s decentralised health system, health services are provided by the government and by churches, the latter ‘operating over 50% of the rural health service network but heavily dependent’ on government funding (Grundy et al., Citation2019, p. xix). The large provincial hospitals (22 in total) are managed by The National Department of Health and the health centres, rural hospitals and aid and community health posts are the responsibility of the provincial and local governments (Grundy et al., Citation2019, p. xix). Provincial hospitals, often located in more populated, urban areas, are the referral hospitals for more complex cases coming in from rural and remote areas of the province. For those living in these remote and rural areas and requiring immediate assistance for common illnesses, they can first access aid posts or community health posts, which are basic, usually one room facilities typically staffed by one to two people. Health centres, which are offered in more populated areas of a district, provide more integrated and wide-ranging services, and in-patient and outpatient care (Thomason et al., Citation1991, p. 31).

The decentralisation of the Papua New Guinea health system is undergoing reforms and the fact that it has not been fully realised poses a problem for populations who are cut-off from life-saving treatments or who are impacted by infectious diseases, such TB. TB incidence rates in Papua New Guinea (432/100,000 population per annum) are amongst the highest in the world (WHO, Citation2020) and incidence is noticeably higher in some areas of the country including the South Fly District of Western Province and the National Capital District (Aia et al., Citation2016). In 2014 an emergency response plan was initiated due to an ongoing outbreak of MDR-TB on Daru Island in the South Fly District of Western Province. The Papua New Guinea National Department of Health convened a multisector response, and the entire Western Province was declared an MDR-TB hotspot. In 2017, the case notification rate for all TB in the South Fly District was 736/100,000 population (Morris et al., Citation2019). The outbreak has since been stabilised (Morris et al., Citation2019), but experts caution that the risk of TB transmission in the area remains high (Specialist Health Service, Citation2019). More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic compromises the gains made to date in Papua New Guinea’s TB response.

The Government of Papua New Guinea put into action the National Tuberculosis Strategic Plan 2015–2020 (Papua New Guinea Government, Citation2015), which supported the implementation of TB services through 275 health facilities or Basic Management Units, along with services offered in the provincial capitals. The purpose of the Basic Management Units is to ensure that: 1. TB can be diagnosed; 2. a person is registered as a TB case; and 3. a person with TB is treated. It should be noted that most of these sites only provide DS-TB services, not MDR-TB. Despite the emphasis on decentralised TB health services through these Basic Management Units, a 2019 review of their facilities identified that less than half of all Basic Management Units had the capacity to diagnose TB (Papua New Guinea Government, Citation2015), with obvious flow on effects to registration and treatment.

Methods

Study context

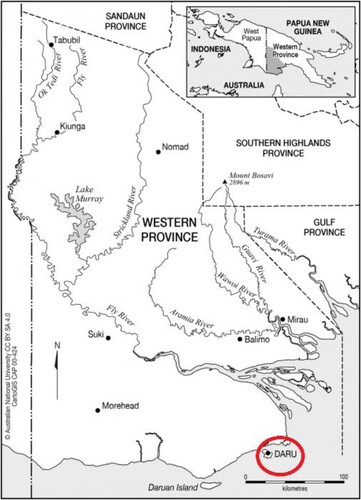

Daru Island is home to the provincial capital of Western Province and is the only urban local level government area in the South Fly District. Western Province (see ) is the only province with its capital, Daru, offshore on an island. In the South Fly District this means that living on the mainland is more rural and remote than living on an island, and subsequently further away from the provincial capital health services. The South Fly District covers an area of 31,864 km2, with Daru Island a mere 14.7 km2. In this district there are five Basic Management Units. However, at the time of this research in 2019, only three were in operation, but not providing the full suite of services. One of these Basic Management Units was on the island of Daru, and two on the coast of the mainland.

Figure 1. The original map was obtained from CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University: https://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/mapsonline/base-maps/western-province-png#.

The two Basic Management Units that were not operational at the time of this study were on the mainland, inland from the coast. At the Basic Management Unit at the provincial hospital, Daru General Hospital, TB diagnostics (including MDR- TB), registration and treatment is provided. The latter is delivered through ‘DART’ sites – Daru Accelerated Response to Tuberculosis- at the hospital and around the island. Community health care workers at the DART sites administer daily TB medication to people on treatment. Therefore, while it is legislated that Basic Management Units should be providing decentralisation of TB diagnosis and treatment services, the model to date remains almost entirely centralised, with Daru General Hospital on the island one of only two health services in South Fly District providing all three TB services (diagnostics, registration, and treatment) for DS- and MDR-TB (Morris et al., Citation2019), resulting in people in rural and remote areas outside of the capital reliant on long-term TB care in this one location.

Research participants, recruitment, and data collection

In this article we highlight case studies from three participants taking part in a large qualitative study conducted in the South Fly District of Papua New Guinea. Simultaneously, we bring in vignettes from other study participants to further reinforce the evidence presented in the case studies. Participants were people on treatment and their family members, community members, and key informants. The findings selected were chosen because they best illustrate, among other issues, access to timely diagnosis and treatment services for people living in rural and remote areas of the South Fly District, the aim of this article. The data presented include people originating from outside the provincial capital in rural and remote areas, but who were residing on Daru Island at the time of the study.

The study explored the social, spatial, and cultural dimensions of TB in the South Fly District. The data set included 128 interviews and 10 focus group discussions with caregivers of children on TB preventive treatment, key informants, community members, community and religious leaders, people on treatment for TB and healthcare workers. Interviews and focus groups were organised and carried out between July 2019 and July 2020 by Papua New Guinean social researchers from the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research (PNGIMR). Recruitment and interviews took place at three sites in the South Fly District: Daru Island, Abam (mainland), and Katatai (mainland). We applied iterative, purposive snowball sampling to recruit participants that bring a wide-range of perspectives to the TB space within this context. Based on the experience of the research team, we believe that the sample sizes of research participants identified was enough to achieve sufficient coverage of the multiple aspects of TB that relate to our specific research aims, ensuring that ‘data saturation’ was achieved. The sample size was extensive enough to ensure rich data that uncovers patterns and variants, particularly in such a diverse ethnic context such as Papua New Guinea.

All interviews and focus groups examined the socio-cultural aspects of TB prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in the South Fly District, including the accessibility and acceptability of services for TB diagnosis and treatment, and how people from rural and remote areas of Western Province came to be on treatment on Daru Island. Interview questions were generally the same across the sample; however, there were some variations. For example, someone on treatment for TB would be asked additional questions about their own pathway to care and treatment experience, whereas a community member or key informant would be asked about community-level issues more broadly for people trying to access TB diagnosis and treatment. Interviews lasted between 1 and 2 h and focus groups lasted between 2 and 3 h. Interviews and focus groups were led by a team of highly experienced male and female bi-lingual (English and Tok Pisin) researchers from PNGIMR. Interviews and focus group discussions were audio-recorded, conducted in English and or a combination of English and Tok Pisin. In a few cases, interviews were supported by a locally engaged speaker of one of the local languages in South Fly District (Kiwai) to support data collection. Datasets were transcribed and where necessary translated into English. A senior researcher then reviewed the translation for quality and accuracy. Translation and transcribing of transcripts were undertaken by staff from PNGIMR in a three-step process. In the first and second step, a transcriber transcribed the audio verbatim and then translated the transcription. In the third step, a senior researcher undertook a quality and accuracy check to ensure both translation and interpretation was correct and captured the meaning of the participants. The transcription and coding of data began immediately after the in-depth interviews were completed and continued after the focus group discussions.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis approach was utilised for all data, whereby all data transcripts were coded in NVIVO 12 in a process of analytical induction, focusing on the identification of recurrent patterns (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). Coding of transcripts were cross-checked for consistency by research staff in Papua New Guinea and Australia and revised considering emergent themes. Initial codes were analysed in detail by researchers in Australia to identify sub-themes as well as differences and similarities within and across the transcripts. This approach is iterative and reflexive, with each piece of data building on the next, to develop overall thematic concepts. It should be noted that while we only present select findings in this article, the themes identified in the ‘Results’ section were evident across most interviews and focus groups and spoken to in varying degrees.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the PNGIMR Institutional Review Board, the PNG National Department of Health’s Medical Research Advisory Committee, and the Human Research Ethics Committee of UNSW Sydney. The study was endorsed by the Western Provincial Health Authority in Papua New Guinea.

For the interviews and focus group discussions, written consent forms were obtained from the study participants who were literate, while witnesses signed on behalf of those who were unable to read and write. Participants were also given the option of giving verbal consent. All participants were informed of the study by key informants working in outpatient and inpatient medical services in the study sites and explained what would be required from them. Copies of the consent form were not provided until after the participant agreed to participate in the study and had met with a member of the research team to go through the form. At this time, participants were given time to ask the researcher any questions they had and/or to discuss concerns. Consent forms were developed by PNGIMR and UNSW and have received ethics approval. Participants were reimbursed for their time, with refreshments and a small sum of money given.

All people referred to in the ‘Results’ section have been provided a pseudonym.

Results

Participants had to manage multiple hurdles at once as they actively sought ways and means to manage symptoms before getting a referral, or self-referring, to TB services on Daru Island. As such, the narratives that follow inevitably include elements of each theme, some more prominent than others.

Lack of financial assistance

According to Lewis, a community member from mainland South Fly District, the centralisation of TB services on Daru Island means those outside of the capital who are without the financial means to travel by air or dinghy must wait, sometimes for a prolonged period of time, until their circumstances change:

Sometimes our families are from a far place. If they don’t have money to travel from that place to Daru, to take the patient to Daru quickly … they will have to wait until when they make money. When they get money then they will take the patient to Daru. If not, they just keep the patient in the village.

There is one community health post near Brad’s village, and in the Basic Management Unit where he lives there is no capacity to diagnose TB. But Brad knew the signs and symptoms of TB. Having attended an awareness session on TB when in high-school, he had learnt to read TB on the body: ‘Nobody told me that I was sick … when I was feeling and I saw the signs on my body, I knew that, totally I knew that I got TB sickness.’ Knowing that TB was airborne, Brad tried his best to limit his family’s exposure to the bacteria. As he recalled: ‘I was avoiding my family … I don’t sit to where wind blows. I used to tell them. I was honest to them because I don’t want another problem to come in the family again.’

Like most Papua New Guineans living in the village, Brad and his family were largely self-sufficient, any small income generated from marketing was used to supplement their very simple needs. The absence of TB diagnostic services meant he and his family needed to find ways to self-fund travel to Daru. The costs associated with staying in Daru for treatment would become a challenge for his extended family. Brad’s wife took on paid work in another village to access the cash needed to pay for the transport between Brad’s village and Daru. In the ensuing months she was able to save the 150 PGK (∼$57 AUD) needed to pay for the journey but securing the money to pay for the trip was not the only challenge they faced. They experienced further delays because they could not find a dinghy that could make the one-day journey. In the time from when Brad first made sense of the symptoms as they appeared on his body, could save the necessary money, and find an available dinghy to travel to Daru, Brad was close to death: ‘I nearly lost my life … Sometimes when I coughed, coughed, coughed, I spit blood and I saw that I was going [sic] worse.’ Waiting some seven months, and with very little else in the way of treatment, Brad could only, and quite reasonably, turn to prayer. He was not using prayer as a healing modality (Aldridge, Citation2002); he was using prayer to access biomedical treatment: ‘I was seeking in prayer to God that, “Please, send me transport, make it hurry up to Daru”.’

By the time Brad arrived in Daru to stay with his biological sister he had undergone such significant weight loss that she no longer recognised him. Still concerned for his family and the risk of infecting others, he declared on his arrival: ‘I won’t be here for long and this is airborne disease, I might spoil all of you. I’ll be here just one night, sleeping underneath your house and then I’ll go … It’s a safety side too; all of us might get into problem.’ The next morning Brad went to the hospital where he was admitted and diagnosed with MDR-TB and immediately started treatment.

Having safely delivered Brad to Daru, his wife and two children returned to their village because life in Daru is both difficult and expensive. Another person on treatment for MDR-TB, Stanford, also had to leave his wife and children back in his village for the same reasons as Brad. As he noted when thinking about his two-year treatment duration, ‘shit I’m going to miss my family.’

People in Daru experience severe overcrowding, a lack of water, sanitation, and hygiene, and food insecurity (Adepoyibi et al., Citation2019; Jops et al., Citation2022). It was the hope of both Brad and Stanford that TB services would become more accessible to people living outside of Daru. Concerned by the lack of diagnostic and treatment facilities where he lives, even more so about the poor living conditions on Daru Island, Brad believes TB services, particularly treatment, must be bought to remote areas:

We should set [up] some DART sites in the village and rural areas too because of transport and transport payment is very expensive when people are coming from my area on the mainland. And people from the mainland are really suffering here [in Daru] from food [insecurity] and [problems with] accommodation.

The use of traditional healing and a lack of transport

Transport was a major issue that came up for many participants living outside of Daru. For those able to access transport, the journey to Daru may take days. David, the husband of a woman with MDR-TB explained that when his wife started showing TB symptoms, and because there were no health services in his village, they had to walk four to five hours to the mouth of the river just to catch the dinghy to Daru. Even if transport is secured, additional factors need to be considered. As Zebulun, a man with DS-TB explained: ‘[transport time] depends on the weather pattern. When the weather at that time, when it is rough, the boat needs to take extra care.’

In a village on a riverbank near the mouth of the Fly River, the second longest river in Papua New Guinea, Leo, a fisherman, lives with his wife, and teenage daughter Helen. Leo earns money from selling his daily catch at the local market. There are no health services in his village and surrounding area: ‘it’s only [us], we survive ourselves there … We protect ourselves from sick,’ says Leo. Transport options are also limited here. Leo was unfamiliar with the signs and symptoms of TB as they first began to show in his daughter Helen. Helen’s earliest symptoms of TB started with headaches and a cough, followed closely by weight loss. She endured these symptoms for six months before she was able to receive her diagnosis in Daru and start treatment. Leo said:

People were saying about Helen, ‘her body is losing weight and her sick is getting worse. How can we support you with the transport to take you to Daru?’ So, we have no transport too, so we just stay like this until any good transports come in which can support you to take you to Daru. So just wait. I was just waiting, waiting …

During the six months they waited for transport, Leo and his wife used traditional methods to manage Helen’s symptoms:

We used to make hot water and mix with some tree leaves to wash her with … . Bring those leaves, just put them inside the hot water, okay after it gets a bit hot, we take it out and we wash her with that. So, we were just supporting her like that in the village … our cultural way of living in the village. The old people used to tell us stories, ‘this tree [leaf], they can support the sick person’

After sleeping the first night with wantoks [kin or community members who speak the same dialect], Helen was taken by ambulance to the provincial hospital where she was diagnosed with DS-TB. Speaking from Daru where Helen was still receiving treatment, Leo spoke of the challenges in accessing TB diagnostics and treatment services, and of the financial burden of ongoing treatment in Daru, particularly related to securing food:

I find it hard to find food here because in the village, my food is in the village [can grow it]. Here I have no garden … and I’m not a public servant where I can get money. Sometimes we just stay, just stay … [with] no food

Under-resourced rural health services

The set-up of the health system in rural and remote areas of the South Fly District outside of Daru creates barriers to health-seeking. Local community health posts, aid posts and health centres should be a first point of contact for people seeking advice on their TB symptoms, which should then result in a referral to Daru General Hospital, but because many services are non-operational, lack medicine and/or diagnostics, people experience long delays. One church leader, Mathias, expressed frustration when talking about this situation:

I’m from the Kiwai Islands and I’ve seen around that island; there’s no health services … Every village you go, there is no Aid Post standing. There is no person who is taking care of the Aid Post there. There is no Aid Post Orderly (APO), so what’s really happening?

Sitting on the grass on the grounds of the Daru Hospital that Felana was calling home, the significance of timely diagnosis and treatment for both HIV and TB were apparent. Felana was five years old when we met yet appeared much younger. Suffering severe growth restriction, Felana lived on the mainland with his mother who was unable to finance her own referral (and therefore transport) to Daru; he nearly paid with his life. His story is intimately tied to that of his mother’s.

Living in another large provincial capital and pregnant with her first child, Felana’s mother, Sharon was diagnosed with HIV in 2014. A few months later she was diagnosed with TB. Completing her treatment for TB with treatment support, she returned home to Western Province in 2016. Although she was adherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART) she soon ran out; she was living so remotely she could not re-fill her supply of ART. Her community health post was unstaffed and had long been abandoned, and even the rural hospital was without ART. Instead, she was prescribed and supplied only Septrin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic used to treat and prevent a variety of HIV-associated infections. Sharon was not the only one in our study who was unable to access the medicine she required. Sonja, a person from the mainland on treatment for DS-TB, was put on Amoxicillin and Panadol when she presented to her local health facility with TB symptoms. Her symptoms did not improve so she decided to make her way to Daru, ‘I was getting really worse and then again I went and complained and they put me on that same medicine, but it didn’t help me.’

Unable to access HIV testing to see if her son had been infected with HIV, but suspecting that he was, Sharon told us that Felana was started on Septrin. During this time Felana was also suffering from a swollen stomach, a well-documented symptom of extrapulmonary TB, and his health was deteriorating. He had not grown as one would expect, and at four he was still not walking.

Without a provincial health supported and funded referral to Daru to be re-supplied ART for herself and to have Felana tested for HIV, and treated as indicated, Sharon chose to supplement her son’s reliance on Septrin with traditional herbs:

I used to look for some sort of herbs and all those and treat him with that. For four years he was not [even] getting any HIV and AIDS medicine. I kept him like that just with herbs.

He is a small child. I can’t bring him right across this way … . Because of the waves and its long distance and following this route; it’s really rough so that’s why I couldn’t bring him this way.

Please you have to send us to Daru. I can’t take this Septrin for years. Please, can you just refer me down to Daru and I can get the real supply because in Daru, they’ve got HIV medicine.

She got really angry with them [hospital health care workers] and she told them, ‘If you people don’t put him on a plane and send him to Daru, I’m going to take you people to court.’ So they sent us this way and we came by force; if not, they wouldn’t have send us this way if we were just easy with them.

Discussion

The people in our study highlighted several challenges to both timely diagnosis and subsequent treatment for those from rural and remote areas of the South Fly District in accessing TB services on Daru Island. The delays recalled in this study varied anything from several weeks to several months. The narratives demonstrate that the people seeking care are consciously and actively navigating barriers in the process of getting a referral or self-referral to TB health services. The narratives expose a fragile and under-resourced primary health care system, along with the limitations of the decentralisation of TB services as per the national policy within this geographically complex setting. In low- and middle-income countries centralised health services have long been acknowledged to marginalise communities in rural and remote areas from accessing essential primary health services (Abimbola et al., Citation2019; The World Bank, Citation1987), and this appears to be the case for those in rural and remote South Fly District trying to access centralised TB services on Daru Island.

In the narratives, people spoke of the geographical barriers that hinder access to services offshore on Daru, resulting in the self-management of TB symptoms. For those able to access transport from the mainland, the journey to Daru may take days and include transport on foot and by boat, the latter unpredictable and influenced by weather patterns. Transport is costly and often difficult to find. Similar findings have been reported in rural areas of Ethiopia, China, and Nepal where people with TB experienced delays in accessing TB services due to geographic location and poor transport infrastructure, which resulted in costly financial burdens (Asemahagn et al., Citation2020; Gele et al., Citation2010; Hutchison et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2013; Marahatta et al., Citation2020; Tadesse et al., Citation2013). A lack of financial support limits what people can afford and how quickly they can access diagnosis, and a lack of financial support also puts pressure on families who have no other choice but to stay in Daru during treatment, having left behind essential resources in the village. This can potentially lead to catastrophic costs where ‘the total cost related to TB management exceeds 20% of the annual pre-TB household income’ (Ghazy et al., Citation2022, p. 1).

In this article, we focused on the structural and health system impediments bought about by the model of TB care being carried out in the South Fly District, as opposed to flaws in an individual’s knowledge of TB or health seeking behaviour, often the focus in understanding delays to timely services. Even if education and awareness campaigns are ramped up in rural and remote areas, it will not change the fact that there are no accessible TB services. Those who advocate for health education around TB symptoms often do so under the assumption ‘that “lack of knowledge about TB” determines care seeking among patients’ and contributes to delays (Lambert & Van der Stuyft, Citation2005, p. 945). This, however, was not the case for the people in our study. Indeed, it was not typically patient delays that were reported. Many knew the symptoms of TB and were desperate to access biomedical services at Daru General Hospital as quickly as possible, often using traditional methods until this occurred. This is not uncommon in the context of TB elsewhere in the Pacific, as people have been reported to turn to customary practices because of inaccessibility to formal health services due to cost and distance from these services (Massey et al., Citation2012; K. A. Viney et al., Citation2014); it is a pragmatic choice. Some of the people we interviewed experienced their health deteriorating to a dangerous state for weeks or months before they were diagnosed with TB. They and their families actively sought ways to obtain diagnosis and treatment; they did not give up on their pursuit to obtain these life-saving TB services. Their journeys to seek care ‘occurred along a continuum of agency and choice’ where their own determination, along with support from social networks ‘shaped their care trajectory’ (Antoniades et al., Citation2018, p. 1385). They showed extraordinary resilience considering they were either experiencing debilitating symptoms themselves or caring for someone who was.

Participants recommended that TB services must be developed in rural and remote areas outside of Daru, which would mean decentralisation must happen more fully. For some in Daru, decentralisation of TB treatment is the provision of treatment at DART sites outside the hospital; having a DART site outside the hospital, but still on the island is not enough. Based on the findings from this study, we support efforts to decentralise TB services to the wider South Fly District, which would allow for the creation of health services that are accessible and responsive to the populations in their catchment area. Studies have demonstrated that the decentralisation of TB services to the primary care level can improve TB detection rates in rural and remote settings (Maha et al., Citation2019; Méda et al., Citation2014; Wei et al., Citation2008) as well as treatment outcomes and delivery of preventive treatment (Zawedde-Muyanja et al., Citation2018). A study in Uganda showed that an integrated approach to the implementation and strengthening of decentralised TB services for children improved case detection in both adults and children, as well as healthcare worker knowledge of TB, functionality of diagnostics and availability of anti-TB medicines (Dongo et al., Citation2021).

The government of Papua New Guinea aims to achieve a goal of universal health coverage, with the need for improved primary care access and quality widely recognised at all government levels (PNG National Department of Health, Citation2010). While the decentralisation of health services across the country is underway and ongoing in order to improve access to health service delivery, the process is slow, under-resourced (Grundy et al., Citation2019) and virtually non-existent for TB services in the South Fly District. Decentralised TB care has been part of the Western Provincial Health Authority plans since 2014 (and prior) (Morris et al., Citation2019); however, a lack of financial and human resources remains a significant challenge. A recent study (Maha et al., Citation2019) undertaken in East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea, showed that the decentralisation of select TB services from the larger provincial facilities to the district level had a positive impact on attendance at TB diagnostic services and the authors concluded that more resources needed to be allocated into small-scale community based interventions at this level ‘in order to improve TB treatment outcomes and promote equitable access to health services’ (Maha et al., Citation2019, p. S48). We support this conclusion and argue that such a person-centred approach that addresses the needs of individuals in the community through accessible and responsive health services should be prioritised. This would create a fair model of TB support for those living outside of Daru.

Decentralisation of services for TB must be one component of a broader health systems strengthening approach, and the COVID pandemic has further highlighted the need for more community-based resources and response. Diagnosis itself requires a whole system strengthening approach – and the fact that battery operated, portable, hand-held devices are now being developed for sputum testing using an Xpert Ultra or Truenat platformFootnote2 provides a potential way forward. Community-based models of care versus facility based could also be explored. Doing the basics well at a community level will have much greater benefit than resources being concentrated in the provincial or referral facilities. Similarly, if efforts to eliminate TB are to be actualised, TB prevention through active case detection must also be decentralised.

In the 2019 Independent State of Papua New Guinea Health System Review the authors (Grundy et al., Citation2019, p. xx) state that funding is needed for health infrastructure and to address a major human resource deficiency for health in rural and remote areas, and they conclude that the allocation of government resources needs ‘to be developed and aligned with the decentralised planning system to ensure more equitable patterns of resource allocation across the country.’ As recently as December 2021, the WHO Acting Country Representative for Papua New Guinea (Maalsen, Citation2021), speaking at the launch of the Papua New Guinea National Health Plan 2021–2030, stressed the importance of investing resources in aid posts and community health posts in rural and remote areas and providing primary health care for people in their ‘home environments.’ Aligned with this, and with regards to TB, we believe a first step would be the reopening and resourcing of the closed Basic Management Units on mainland South Fly District with the capacity to both diagnose and treat TB. Basic Management Units that are accessible for people in rural and remote areas would allow people to be treated near their homes and alleviate the financial pressure placed on them for transport and relocation costs, and importantly, allow for timely diagnosis and treatment, reducing delays. Additional funding could be allocated for outreach services and transport support for those cases that, nevertheless, remain isolated due to their geographical location. The provision of social protection interventions, such as conditional cash transfer schemes for TB could be explored to alleviate the high costs and financial burden often related to TB care (K. Viney et al., Citation2019) and potentially improve treatment outcomes (Ukwaja, Citation2019).

While localised solutions and recommendations can be sought from health care workers and people living in these areas of Papua New Guinea to determine how to respond best when people are physically cut-off from health services, it is essential to also address the overarching structural factors that disadvantage individuals and are beyond their control, such as inadequate health infrastructure. These factors need to be responded to through government intervention; the burden currently placed on individuals and families on the mainland are simply too high. The under-resourced health system also puts additional pressure on rural healthcare workers who are doing their best to provide care amidst medicine shortages and a lack of diagnostics services. It should be noted here that health care workers in these settings have to be realistic in their approach- as the anthropologist Alice Street found in her study of Madang General Hospital in Papua New Guinea’s north coast, when facilities are under-resourced, doctors apply ‘pragmatic clinical strategies to manage patients using the treatments available’ (Street, Citation2014, p. 211). Health care workers in these constrained settings are doing their best to manage complex health situations considering the limitations of the health system and the lack of medicines available to them.

This study has some limitations that can be addressed in future research. Firstly, we did not conduct an economic assessment of the actual financial burden faced by the individual person on treatment and their families. This was beyond the scope of the study. Nor did we design this as a health systems study. We designed the study to be socio-cultural. As such, it was not set-up to look at the different pillars of the health system which could inform future decentralisation models. The study does, however, fill an evidence gap as, in contrast to HIV, TB-related qualitative research in Papua New Guinea has been very limited (Diefenbach-Elstob et al., Citation2017; Marme, Citation2018; Whittaker et al., Citation2009). Our study integrates a social, cultural, and spatial dimension to TB research, a crucial component which to date has been largely overlooked in Papua New Guinea. Additionally, our study included a substantial dataset that included people from mainland South Fly District and Daru Island. The people we interviewed were eager to tell their stories. Data generated included a high level of detail and description, and we believe the knowledge gained will be crucial when advocating for an equitable and responsive health system within this context.

Conclusion

We need to look beyond Daru … Let us all, us partners, extend their support and expertise to those places so that we are talking about Western Province, we aren’t just talking about Daru. We need to focus on decentralising care, but also providing support to those places [rural and remote] so that it becomes a truly Western Province TB response. -Dr. Stavis, TB Program Partner

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The WHO (Citation2015, p. 2) defines ‘passive tuberculosis case finding’ as

a patient-initiated pathway to TB diagnosis involving: (1) a person with active TB experiencing symptoms that he or she recognizes as serious; (2) the person having access to and seeking care, and presenting spontaneously at an appropriate health facility; (3) a health worker correctly assessing that the person fulfils the criteria for suspected TB; and (4) the successful use of a diagnostic algorithm with sufficient sensitivity and specificity to diagnose TB.

2 Recently evaluated in PNG as of part of a study supported by FIND: The Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics.

References

- Abimbola, S., Baatiema, L., & Bigdeli, M. (2019). The impacts of decentralization on health system equity, efficiency and resilience: A realist synthesis of the evidence. Health Policy and Planning, 34(8), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz055

- Adepoyibi, T., Keam, T., Kuma, A., Haihuie, T., Hapolo, M., Islam, S., Akumu, B., Chani, K., Morris, L., & Taune, M. (2019). A pilot model of patient education and counselling for drug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Papua New Guinea. Public Health in Action, 9(Suppl 1), S80–S82. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.18.0096

- Aia, P., Kal, M., Lavu, E., John, L. N., Johnson, K., Coulter, C., Ershova, J., Tosas, O., Zignol, M., Ahmadova, S., & Islam, T. (2016). The burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Papua New Guinea: Results of a large population-based survey. PLoS One, 11(3), e0149806. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149806

- Aia, P., Lungten, W., Fukushi, M., Kisomb, J., Yasi, R., Kal, M., & Islam, T. (2018). Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Papua New Guinea: Analysis of case notification and treatment-outcome data, 2008–2016. Western Pacific Surveillance & Response Journal, 9(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5365/wpsar.2018.9.1.006

- Aldridge, D. (2002). Prayer and spiritual healing in medical settings. In Handbook of ethnotherapies (Vol. 65, pp. 1–11). USA: The International Journal of Healing and Caring.

- Antoniades, J., Mazza, D., & Brijnath, B. (2018). Agency, activation and compatriots: The influence of social networks on health-seeking behaviours among Sri Lankan migrants and Anglo-Australians with depression. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(8), 1376–1390. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12764

- Asemahagn, M. A., Alene, G. D., & Yimer, S. A. (2020). Geographic accessibility, readiness, and barriers of health facilities to offer tuberculosis services in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia: A convergent parallel design. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine, 11, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S233052

- Balestra, G., & Kelly-Hanku, A. (2021). ‘Mi No TB Man’: A qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of TB and TB treatment in two high burden provinces in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea.

- Bello, S., Afolabi, R. F., Ajayi, D. T., Sharma, T., Owoeye, D. O., Oduyoye, O., & Jasanya, J. (2019). Empirical evidence of delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 820. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7026-4

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Cai, J., Wang, X., Ma, A., Wang, Q., Han, X., & Li, Y. (2015). Factors associated with patient and provider delays for tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 10(3), e0120088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120088

- Cairns, A., Witter, S., & Hou, X. (2018). Exploring factors driving the performance of rural health care in Papua New Guinea.

- Canetti, D., Riccardi, N., Martini, M., Villa, S., Di Biagio, A., Codecasa, L., Castagna, A., Barberis, I., Gazzaniga, V., & Besozzi, G. (2020). HIV and tuberculosis: The paradox of dual illnesses and the challenges of their fighting in the history. Tuberculosis (Edinb), 122, 101921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2020.101921

- Diefenbach-Elstob, T., Plummer, D., Dowi, R., Wamagi, S., Gula, B., Siwaeya, K., … Warner, J. (2017). The social determinants of tuberculosis treatment adherence in a remote region of Papua New Guinea. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3935-7

- Dongo, J. P., Graham, S. M., Nsonga, J., Wabwire-Mangen, F., Maleche-Obimbo, E., Mupere, E., Nyinoburyo, R., Nakawesi, J., Sentongo, G., Amuge, P., Detjen, A., Mugabe, F., Turyahabwe, S., Sekadde, M., & Zawedde-Muyanja, S. (2021). Implementation of an effective decentralised programme for detection, treatment and prevention of tuberculosis in children. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 6(3), 131. https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/6/3/131. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030131

- Eves, R., & Kelly-Hanku, A. (2020). Medical pluralism, pentecostal healing and contests over healing power in Papua New Guinea. Social Science & Medicine, 266, 113381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113381

- Gele, A. A., Sagbakken, M., Abebe, F., & Bjune, G. A. (2010). Barriers to tuberculosis care: A qualitative study among Somali pastoralists in Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes, 3(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-86

- Ghazy, R. M., El Saeh, H. M., Abdulaziz, S., Hammouda, E. A., Elzorkany, A. M., Khidr, H., Zarif, N., Elrewany, E., & Abd ElHafeez, S. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the catastrophic costs incurred by tuberculosis patients. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04345-x

- Grundy, J., Dakulala, P., Wai, K., Maalsen, A., & Whittaker, M. (2019). Independent state of Papua New Guinea health system review. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia.

- Ho, J., Fox, G. J., & Marais, B. J. (2016). Passive case finding for tuberculosis is not enough. International Journal of Mycobacteriology, 5(4), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmyco.2016.09.023

- Honjepari, A., Madiowi, S., Madjus, S., Burkot, C., Islam, S., Chan, G., Majumdar, S. S., & Graham, S. M. (2019). Implementation of screening and management of household contacts of tuberculosis cases in Daru, Papua New Guinea. Public Health in Action, 9(Suppl 1), S25–S31. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.18.0072

- Hutchison, C., Khan, M. S., Yoong, J., Lin, X., & Coker, R. J. (2017). Financial barriers and coping strategies: A qualitative study of accessing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and tuberculosis care in Yunnan, China. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4089-y

- Jops, P., Kupul, M., Trumb, R. N., Cowan, J., Graham, S. M., Bell, S., Majumdar, S., Nindil, H., Pomat, W., Marais, B., Marks, G., Vallely, A. J., Kaldor, J., & Kelly-Hanku, A. (2022). Exploring tuberculosis riskscapes in a Papua New Guinean ‘hotspot’. Qualitative Health Research, Article 10497323221111912. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323221111912

- Kelly-Hanku, A., Aggleton, P., & Shih, P. (2018). I shouldn’t talk of medicine only: Biomedical and religious frameworks for understanding antiretroviral therapies, their invention and their effects. Global Public Health, 13(10), 1454–1467. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1377746

- Lambert, M. L., & Van der Stuyft, P. (2005). Editorial: Delays to tuberculosis treatment: Shall we continue to blame the victim? Tropical Medicine and International Health, 10(10), 945–946. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01485.x

- Li, Y., Ehiri, J., Tang, S., Li, D., Bian, Y., Lin, H., Marshall, C., & Cao, J. (2013). Factors associated with patient, and diagnostic delays in Chinese TB patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-156

- Maalsen, A. (2021). Launch of the PNG National Health Plan 2021–2030. From WHO Papua New Guinea Facebook page.

- Macfarlane, J. (2009). Common themes in the literature on traditional medicine in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal, 52(1-2), 44–53.

- Macintyre, M. (2019). Catastrophic failures in PNG health service delivery. https://devpolicy.org/catastrophic-failures-in-png-health-service-delivery-20190404/

- Macintyre, M. B., Foale, S. J., Bainton, N. A., & Moktel, B. (2005). Medical pluralism and the maintenance of a traditional healing technique on Lihir, Papua New Guinea

- Maha, A., Majumdar, S. S., Main, S., Phillip, W., Witari, K., Schulz, J., & du Cros, P. (2019). The effects of decentralisation of tuberculosis services in the East New Britain province, Papua New Guinea. Public Health in Action, 9(Suppl 1), S43–S49. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.18.0070

- Makwakwa, L., Sheu, M.-l., Chiang, C.-Y., Lin, S.-L., & Chang, P. W. (2014). Patient and health system delays in the diagnosis and treatment of new and retreatment pulmonary tuberculosis cases in Malawi. BMC Infectious Diseases, 14(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-132

- Marahatta, S. B., Yadav, R. K., Giri, D., Lama, S., Rijal, K. R., Mishra, S. R., Shrestha, A., Bhattrai, P. R., Mahato, R. K., & Adhikari, B. (2020). Barriers in the access, diagnosis and treatment completion for tuberculosis patients in central and western Nepal: A qualitative study among patients, community members and health care workers. PLoS One, 15(1), e0227293. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227293

- Marme, G. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to effective tuberculosis infection control practices in Madang Province, PNG - a qualitative study. Rural and Remote Health. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4401

- Massey, P. D., Wakageni, J., Kekeubata, E., Maena'adi, J., Laete'esafi, J., Waneagea, J., Fangaria, G., Jimuru, C., Houaimane, M., Talana, J., MacLaren, D., & Speare, R. (2012). TB questions, East Kwaio answers: Community-based participatory research in a remote area of Solomon Islands. Rural and Remote Health, 12, 2139. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH2139

- Méda, Z. C., Huang, C.-C., Sombié, I., Konaté, L., Somda, P. K., Djibougou, A. D., & Sanou, M. (2014). Tuberculosis in developing countries: Conditions for successful use of a decentralized approach in a rural health district. The Pan African Medical Journal, 17, 198–198. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.17.198.3094

- Morris, L., Hiasihri, S., Chan, G., Honjepari, A., Tugo, O., Taune, M., Aia, P., Dakulala, P., & Majumdar, S. S. (2019). The emergency response to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Western Province, Papua New Guinea, 2014–2017. Public Health in Action, 9(Suppl 1), S4–S11. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.18.0074

- Oga-Omenka, C., Wakdet, L., Menzies, D., & Zarowsky, C. (2021). A qualitative meta-synthesis of facilitators and barriers to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10173-5

- Papua New Guinea Government. (2015). National tuberculosis strategic plan (NSP) for Papua New Guinea. Port Moresby, PNG.

- PNG National Department of Health. (2010). National health plan 2011–2020 for Papua New Guinea. In. Papua New Guinea.

- Specialist Health Service. (2019). TB prevention and control in PNG: Report of the review of contribution of DFAT investments (2011–2018). https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/papua-new-guinea-review-dfat-support-tb-response-png-2011-2018.pdf

- Sreeramareddy, C. T., Panduru, K. V., Menten, J., & Van den Ende, J. (2009). Time delays in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review of literature. BMC Infectious Diseases, 9(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-9-91

- Storla, D. G., Yimer, S., & Bjune, G. A. (2008). A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-15

- Street, A. (2014). Biomedicine in an unstable place: Infrastructure and personhood in a Papua New Guinean hospital. Duke University Press.

- Tadesse, T., Demissie, M., Berhane, Y., Kebede, Y., & Abebe, M. (2013). Long distance travelling and financial burdens discourage tuberculosis DOTs treatment initiation and compliance in Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 424. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-424

- Teo, A. K. J., Singh, S. R., Prem, K., Hsu, L. Y., & Yi, S. (2021). Duration and determinants of delayed tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in high-burden countries: A mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiratory Research, 22(1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01841-6

- The World Bank. (1987). Financing health services in developing countries.

- Thomason, J., Newbrander, W., & Kolehmainen-Aitken, R.-L. (1991). Decentralization in a developing country: The experience of Papua New Guinea and its health service. National Centre for Development Studies, Australian National University.

- Ukwaja, K. N. (2019). Social protection interventions could improve tuberculosis treatment outcomes. The Lancet Global Health, 7(2), e167–e168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30523-0

- Viney, K., Islam, T., Hoa, N. B., Morishita, F., & Lönnroth, K. (2019). The financial burden of tuberculosis for patients in the Western-Pacific Region. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 4(2), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4020094

- Viney, K. A., Johnson, P., Tagaro, M., Fanai, S., Linh, N. N., Kelly, P., Harley, D., & Sleigh, A. (2014). Tuberculosis patients’ knowledge and beliefs about tuberculosis: A mixed methods study from the Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 467–467. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-467

- Wei, X., Liang, X., Liu, F., Walley, J. D., & Dong, B. (2008). Decentralising tuberculosis services from county tuberculosis dispensaries to township hospitals in China: An intervention study. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 12(5), 538–547. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2008/00000012/00000005/art00011

- Whittaker, M., Piliwas, L., Agale, J., & Yaipupu, J. (2009). Beyond the numbers: Papua New Guinean perspectives on the major health conditions and programs of the country. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal, 52(3-4), 96–113.

- World Bank. (2020). The World Bank in Papua New Guinea. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/png

- WHO. (2006). Diagnostic and treatment delay in tuberculosis. In WHO Regional Office for the Eastern, Mediterranean.

- WHO. (2014). The end TB strategy: Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. https://www.who.int/tb/strategy/End_TB_Strategy.pdf?ua=1

- WHO. (2015). Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: An operational guide https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/181164/9789241549172_eng.pdf

- WHO. (2019). Global tuberculosis report 2019. file:///C:/Users/z3104610/Downloads/9789241565714-eng.pdf

- WHO. (2020). Global tuberculosis report 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131

- WHO. (2021a). Global tuberculosis report. file:///C:/Users/z3104610/Downloads/9789240037021-eng%20(5).pdf

- WHO. (2021b). Tuberculosis: Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- Zawedde-Muyanja, S., Nakanwagi, A., Dongo, J. P., Sekadde, M. P., Nyinoburyo, R., Ssentongo, G., Detjen, A. K., Mugabe, F., Nakawesi, J., Karamagi, Y., Amuge, P., Kekitiinwa, A., & Graham, S. M. (2018). Decentralisation of child tuberculosis services increases case finding and uptake of preventive therapy in Uganda. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 22(11), 1314–1321. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.18.0025