ABSTRACT

As the cohort of People Living with HIV (PLHIV) ages, so does the spectrum and burden of non-AIDS define HIV-associated conditions (NARC). PLHIV are likely to need different and increased healthcare services. It requires health systems to adapt to this disease trend and conform to a chronic care model, which respects the distinct needs of the ageing population. In this article, we explore the lived experiences of PLHIV and their healthcare providers in managing the challenges of dealing with NARC in Arba Minch, Southern Ethiopia. This study utilises interpretative substantive methods, encompassing qualitative interviews and Focus Group Discussions. The Normalisation Practice Theory (NPT) guided the semi-structured questions concerning routine screenings and current models of HIV care for ageing individuals. The main structural challenges in providing adequate geriatric care included: (i) the lack of awareness of the risk of NARCs; (ii) the absence of blended care; (iii) an HIV-centred approach exclusive of multidisciplinary care; and (iv) financial constraints. In an era with increasing NARCs, traditional HIV care models must adapt to the emerging challenges of a ‘greying’ and growing population.

Introduction

Since the early 1980s, major advances in the treatment for People Living with HIV (PLHIV) have been made (Eisinger & Fauci, Citation2018). The availability of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV from a progressive and often fatal infection to a more manageable and chronic disease (Fauci & Lane, Citation2020). Since 2010, AIDS-related mortality has declined by about 42% and PLHIV are approaching a near-normal life expectancy (Sabin & Reiss, Citation2017; Trickey et al., Citation2017; UNAIDS, Citation2021). Consequently, the prevalence of PLHIV aged 50 + is increasing. However, this ‘greying’ of HIV prevalence poses emerging challenges for health systems (Harris et al., Citation2018). Non-AIDS defining HIV-associated conditions (NARC), which are associated with long term use of ART and accelerated ageing due to HIV, are now the leading cause of death in PLHIV (Brew & Cysique, Citation2017; Deeks et al., Citation2013). Compared to other adults, PLHIV experience a greater occurrence of cardiovascular disease (McGettrick et al., Citation2018), musculoskeletal disease (Walker-Bone et al., Citation2016), metabolic abnormalities (Willig & Overton, Citation2016), neurocognitive impairments (Cysique & Brew, Citation2019; Harling et al., Citation2019) and ageing-related syndromes such as frailty and gait impairment (Falutz, Citation2020; Guaraldi & Milic, Citation2019).

Ethiopia's publicly funded health-delivery service system is three-tiered, including primary hospitals and healthcare units, general hospitals at the secondary level, and tertiary services by specialised hospitals. Since 1993, primary health care has been the focus of Ethiopia's health system, recognising a major expansion of primary health care units in the past decade (Falutz, Citation2020; Tiruneh et al., Citation2020). To offer both fundamental and cutting-edge HIV/AIDS services, the primary health care units are connected to district hospitals. In hospitals and health facilities, HIV testing, counselling, ART and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of the virus are all offered. Tertiary hospitals provide care to patients, after reference by the district hospitals (Deribew et al., Citation2018).

There is extensive literature on the structural healthcare challenges and insufficient resources for ageing PLHIV (Emlet & Poindexter, Citation2004; Negredo et al., Citation2017). This inadequate response is said to be largely attributed to a silo-effect in which care for HIV/AIDS and other healthcare activities do not function as joint initiatives, but rather as two separate entities (Negredo et al., Citation2017). Consequently, neither sector is prepared to tackle complex care problems (Emlet & Poindexter, Citation2004; Linsk et al., Citation2003; Osakunor et al., Citation2018). Numerous qualitative studies have identified clinically important gaps in the care for ageing PLHIV, including the lack of support, unclear guidelines and the absence of standardised assessment (Boffito et al., Citation2020; Bosire et al., Citation2020; Greene et al., Citation2018; Levett et al., Citation2020; Rosenfeld et al., Citation2014; Sylla et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, these studies are largely concentrated in Western countries, even though more than two-thirds of PLHIV reside in Sub-Saharan Africa (Siedner, Citation2017). In addition, most studies of ageing with HIV in resource-limited settings have focused on single morbidities, or lack local insight about geriatric care (Godongwana et al., Citation2021; Siedner, Citation2017). Similarly, several investigations have focused on the perspectives of healthcare providers or patients individually, but lack insight into the shared experiences (Boffito et al., Citation2020; Godongwana et al., Citation2021).

Researchers have begun to emphasise the need to work on the definition and implementation of new models that help improve the care and well-being of this group, particularly in the context of fragile health systems and severe resource constraints (Deeks et al., Citation2013; Erlandson & Karris, Citation2019; Perfect et al., Citation2019). To develop useful and impactful interventions, researchers increasingly acknowledge the importance of stakeholder consultation through interviews and FGD (Hawkins et al., Citation2017). This research adds to previous research by entailing the combined lived experiences and routines of health providers and patients, to create an understanding of how the risk of ageing with HIV is perceived. This research aims to create an understanding of the fundamental issues underlying comorbid care for ageing PLHIV from the perspective of people dealing and living with HIV, to inform health interventionists and public policy makers on optimising health care delivery.

Methods

Study design

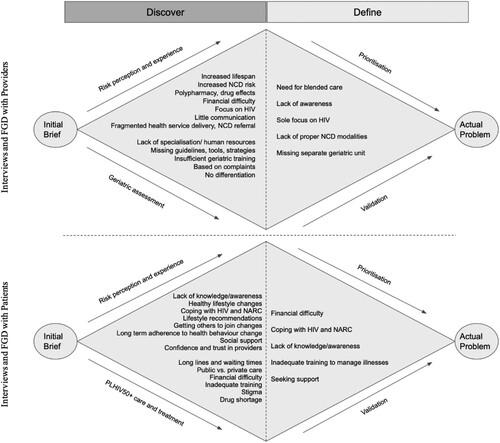

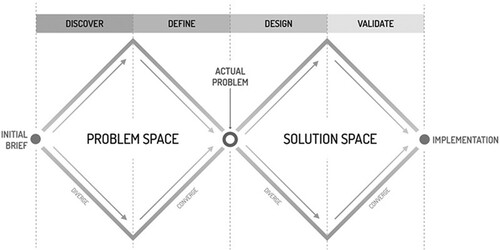

A qualitative phenomenological study was carried out to discover the lived experiences of PLHIV and their providers in managing HIV with multimorbidity. The study included in-depth face-to-face interviews with patients and their providers. In addition, FGDs were organised to ensure triangulation and to define/prioritise the problems that were discovered in the first interviews, entailing a human-centred approach by Melles and colleagues (Melles et al., Citation2020). Various studies have used human-centred design (HCD) to study complex care challenges, as HCD is about discovering human needs and how to respond to those needs (Erwin & Krishnan, Citation2016; Tsekleves & Cooper, Citation2017). This research entails the Diamond Model (), a double-phased model which emphasises the need to first clearly discover and define the problem under research, before finding and designing solutions to the problem. This research focuses on the first diamond to visualise the HCD process, and is used to distinguish the correct problem being investigated and captures the ‘problem space’. The diamond structure highlights the divergent and convergent stages of the design and research processes; a process of studying a topic in a broader and deeper way followed by a more focused approach. First, we begin by questioning the problem of ageing with HIV by examining all the fundamental aspects underlying the problem during individual interviews with patients and providers (understanding). Then, FGDs follow to come to a problem statement by converging and prioritising these issues (defining).

Figure 1. The Diamond Model, adapted from Melles et al. (Citation2020), which visualises the human-centred design process. The diamond is used to discover and define the challenges faced by the older HIV patient.

Study setting and population

At the beginning of 2020, around 620,000 people in Ethiopia were living with HIV. Ethiopia has known considerable progress in the reduction of the burden of HIV/AIDS over the last decades. Nevertheless, the burden remains high. In Ethiopia, around 88% of adults with HIV were on ART in 2020 (Girum et al., Citation2018). As a result, the number of Ethiopian PLHIV50+ has doubled from 85,000 in 2010 to 170,000 in 2019, and they live to be 60–70 years old (Girum et al., Citation2018).

Our study was carried out in four hospitals within Arba Minch, Chencha and Gidole: Arba Minch General Hospital, Arba Minch Sikela Health Centre, Chencha Primary Hospital and Gidole Primary Hospital. The four health centres together hold approximately more than 3500 ART records. The FGDs were held with patients and providers from Arba Minch Hospital.

Arba Minch is a town in the Gamo Gofa zone. It is 505 km from Addis Ababa in southern Ethiopia, and 275 km from Hawassa, the regional capital. The Arba Minch hospital serves a population of over 1.5 million people. It offers a wide range of health services, including outpatients, inpatients, pharmacies, and laboratories, as well as ART. Arba Minch General Hospital has the largest ART clinic in the region with over 1700 ART registries. Arba Minch Sikela Health Centre has the lowest ART records, being 400.

Chencha town is located 40 km northwest of Arba Minch. Chencha Primary Hospital offers outpatient, inpatient, pharmacy, HIV counselling and testing, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, ART clinic, and laboratory services to 800 current cases.

Gidole is the administrative hub of Dirashe special district. It is found in southern Ethiopia, 565 kilometres from Addis Ababa. Gidole Primary Hospital offers all services to the district community and the surrounding area, and holds around 1000 ART clinic records.

Eligibility and recruitment

Convenience sampling was used as local researchers relied on the availability of participants at the health centres. Participants were identified and recruited by research staff (M.G.) (T.T.) (B.S.) of Arba Minch university. Purposive sampling followed, based on the eligibility criteria. Healthcare practitioners who have worked for more than one year with PLHIV and could provide verbal consent were eligible to participate. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were 50 years of age or older, living with HIV and at least one NARC, and on ART for a period of no less than 6 months. There was no requirement on how long one had been living with HIV. Patients were recruited while they visited the ART clinic for routine HIV care.

A minimum sample size of 12 providers and 15 patients was selected a priori for the interviews to capture different types of participants and based on previous literature with similar designs that considered a sample size of 11–25 participants per interview group appropriate (Areri et al., Citation2020; Kiplagat et al., Citation2019). For the two FGDs, the principal investigators aimed to recruit 4–8 patients in one group, and 2–6 doctors in the other group from the Arba Minch General Hospital. Patients and doctors were divided in a separate FGD. Participants for the FGD were required to have participated in the first phase of interviews; therefore, having the same inclusion criteria applied as in the first phase.

Data collection

The data was collected between April and August 2021. Interviews were semi-structured, open-ended, and lasted an average of 30–60 minutes. Interviews with patients were performed in Amharic by an interpreter (B.S.) and recorded on audiotape for later transcription. Interviews with providers were conducted in English or Amharic, depending on the preference of the provider. Amharic recordings were translated and transcribed in English by the interpreter (B.S.). Original English interviews were transcribed verbatim by the main investigators. Participants’ personal information was anonymised to ensure confidentiality. The interview guide was developed based on the Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) of May and Finch (May & Finch, Citation2021). The NPT proposes four constructions that represent different types of work that individuals carry out around the execution of a new practice. Coherence was used to gain a better understanding of the individual lived experience and behaviour of patients and providers in ART settings. The concept of collective action and cognitive participation from the NPT was used to understand relational dynamics and interaction in healthcare settings. Reflexive monitoring was used to understand the participants’ ideas about how (screening) practices ought to be realised. The content of the interviews covered various topics related to the needs and experiences of patients and providers: views on HIV and NARC risk, challenges in identifying and managing these conditions, and concerns about how to cope with future health needs ().

Table 1. Interview guide based on the normalisation practice theory (NPT)

Two FGDs were arranged to address any remaining questions and to ensure validation of the initial findings, according to the ‘converging’ stage of the Double Diamond Model. The FGD guide was based on the ‘Top Five’-tool of the Field Guide for Human Centred Design (CitationIDEO.org. Resources), outlined in . The sessions are held in Arba Minch General Hospital ART clinic and consist of two parts. Part 1 focused on validation and prioritisation of results. Participants in both sessions were asked to brainstorm as a group about the biggest challenges of ageing with HIV. Subsequently, participants had to list the top five of these challenges individually. At the end of part 1, a group discussion revealed which challenges were most important to patients. Part 2 was created to address the data gaps, consisting of a round of questions on important aspects of ageing and HIV.

Table 2. Focus group discussion interview guide.

Data analysis

Thematic content analysis was carried out according to the phenomenological perspective of the study (Vaismoradi et al., Citation2021), with the use of the qualitative data analysis program Atlas.ti9. The transcripts were coded line by line and the categories and subcategories emerged from the grouping of codes of similar content. Discussions with the research team facilitated a reflexive coding process that consisted of reading, coding, reducing and interpreting. The analysis mainly entailed inductive codes that were derived from the data, accompanied by deductive codes from the NPT. A report of quotes and codes was developed to compare, describe and explain the data. Disagreements on the coding process with the team were resolved by consensus.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was ethically approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board of Arba Minch University (IRB/1119/2021; IRB/1120/2021), and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences of Maastricht University (FHML/GH_2020-2021.014; FHML/GH_2020-2021.015). Verbal consent was obtained from all participants prior to conducting the interviews and FGD.

Results

shows the characteristics of the study participants. We conducted 15 interviews with patients and 12 with providers. The patient sample included nine females and six males between the ages of 50 and 73 who had been living with HIV for 16 years on average. In addition to HIV, all the patients were living with at least one NARC. The sample of health care providers included two nurses, seven physicians, and three health officers. Two out of twelve providers had undergone NCD comorbid care training. Five patients and three doctors from Arba Minch General Hospital were available for the FGD.

Table 3. Demographics of study participants.

Two main themes appeared from the data, each including a set of subthemes. The main themes include: (1) Experience with HIV and NARC; and (2) Healthcare requirements. Findings are discussed accordingly.

Theme 1: Experience with the disease

Knowledge and awareness about HIV and ageing

Risk awareness of ageing with HIV

Providers recognised the risk of ageing with HIV, as they see many examples of older PLHIV with multiple diseases in their ART clinics, including cardiac disease, infectious disease, dementia, and lung disease. Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and hypertension were most frequently recognised in older PLHIV: ‘Most commonly, around 50% present cases of diabetes and hypertension’. (HCP4, nurse). In general, patients were aware of the risk of NARC, but were not sure how NARCs are established (i.e. due to HIV, ART, ageing, or an unhealthy lifestyle). During one of the interviews, a diabetic patient stated:

Do you think your diabetes is related to HIV or due to other causes?

I don't know. HIV has been in my blood for the last 15 years. I had been living in lack of restrictions with it [referring to practising an unhealthy lifestyle] as long as I am taking ART drugs. Starting two years back my health is deteriorating. This is however not due to HIV.

What do you think caused it if it wasn't caused by HIV?

It could be [an] inappropriate diet or due to irritability that impaired my pancreas.

Don't you think it is related to ageing?

It is said, but I am physically active. Don't look at my grey hair. I wake up early [in the] morning and I am physically active.

Risk of drug–drug interaction.

Overall, patients agreed that taking their medications routinely was central to leading productive lives. Medication was seen by patients as a lifesaver that enabled them to cope. Providers, however, mentioned medication as a risk factor for developing NCDs and affecting the quality of life of PLHIV. Polypharmacy was believed to influence drug adherence as the pill burden fatigues PLHIV, especially when they have been on ART for a long time. Moreover, providers explained that they face difficulties in prescribing ART and concomitant medications, referring to the risk of side effects and drug–drug interactions: ‘and even the management of opportunistic infections is associated with the drug–drug interaction of HAART’ (HCP11). In the FGD, a doctor mentioned the need for integrated care as different care providers, taking care of the same patient, need to take potential drug–drug interactions into account when prescribing medications.

Risk assessment and education

The PLHIV in this study had been implementing some type of behaviour and/or lifestyle change based on professional advice. However, many raised the issue that providers did not provide them with enough information on how to manage their multiple conditions alongside their HIV. Most of the patients were concerned that the professional advice given was not tailored to the person or the specific comorbidity, but that they all received the same advice. Providers explained this deficiency by the lack of training in geriatrics and NARCs. Consequently, older and younger PLHIV are often treated equally; as illustrated by a health officer (HCP12): ‘We see them as any other case. (…) We don't have practice with a specific focus on geriatrics’.

The focus of care for ageing PLHIV

There was a notable difference in perception between patients and providers on the focus of care. While providers are primarily focused on treating HIV outcomes, HIV is no longer seen as a major threat by patients. Providers feared that as ‘HIV is not a serious disease by itself; however, it would hasten their death’ (HCP4, nurse). On the contrary, PLHIV perceive their HIV as under control, while NARCs have become a constant battle that prevents them from leading a normal life. As one participant stated: ‘HIV is 100% better for me. Even though [there is] no cure for it, if you take the medication, you can live as any healthy person. But diabetes and hypertension added load over me and [is] affecting my health’ (P6).

As the traditional model of care in HIV clinics is designed to manage HIV infection, protocols for NARC are not yet standardised, although it is the patient's biggest worry. The fact that patients worry less about HIV outcomes is also a result of the providers’ constant support in treating HIV. All patients believed that if they adhere to ART drugs and make healthy lifestyle changes, they can age as healthy as any other healthy person.

Providers and patients differed in their care goals. While patients perceived lifestyle changes as critical to staying healthy, providers noted the lack of attention to prevention measures in healthcare settings. As stated by a doctor: ‘ … our goal is focused on the treatment and diagnosing that disease and so on. (…) On prevention … We usually do not practice it’ (HCP8). However, the goal of many providers was to prolong the patients’ lives and increase their quality of life, which is compatible with the patients’ aim of increasing their survival as much as possible. Therefore, all patients noted to apply lifestyle changes, including participating in routine care, having a proper diet, and engaging in physical activity.

Patient-provider and provider-provider relationships

The quality of the patient-provider relationship was important to both parties. Although providers must work with limited resources, they try to use everything in their power, according to the needs of the patients. This was also reflected in the experiences of some older adults, who identified providers as key enablers of good management of their illnesses, and acknowledged their support, especially regarding health information and advice on HIV. This support allowed most patients to lead a productive and healthy life, as one patient put it: ‘Their advice [referring to advice from healthcare professionals] is more than money’ (P2). However, many patients experienced difficulties in establishing trusting relationships with their physicians. The distant relationship was mainly attributed to the fragmentation in care; patients with different conditions are treated by different doctors, at different clinics. Therefore, it is difficult for providers and patients to build strong relationships.

Additionally, providers perceived a good provider-provider relationship as equally important. Providers mentioned being in good contact with their colleagues and having regular discussions about their patients. However, specific conversations on NARCs were uncommon. One health officer (HCP7) cited: ‘It is well known that comorbid conditions are increasing in HIV patients; however, there is no documented data that initiates us to discuss with other medical staff. It did not get our concern to discuss it’. It was discovered that many providers managed comorbid conditions at their own discretion, with little cross-talk on the risk of NARCs. As illustrated by a health officer (HCP5): ‘We do not have such a big concern for comorbidities in HIV patients to discuss with other medical staff; our concern is to manage HIV effectively’.

Theme 2: Healthcare requirements

Clinical experience and quality of care

There was high agreement and frustration among patients and providers about the insufficient quality of current HIV and NARC health services within and around Arba Minch. Some patients complained about missing test results or medical records, therefore having to rerun tests, and causing exhaustion. In accordance, many providers expressed concerns about the health system's readiness to provide ‘full package’ care to older PLHIV living with comorbidities ‘Because sometimes we are giving ART medications only. And if the patient is having other comorbid conditions, actually we are not treating the patient’ (HCP3, doctor). However, multiple interacting risk factors (i.e. depressed immunity, fatigue, ageing) make it difficult for providers to deliver this full package.

Referral

Providers and patients commonly expressed their frustrations with referral systems. Providers indicated to refer their patients to other clinics in case specialised NCD care is needed and HIV facilities do not provide support. Patients were referred most frequently for CT scans and dialysis. However, many providers were hesitant to refer patients when they anticipated long waiting times and under-equipped staff, or unavailability of specialists. Patients particularly experienced long waiting times for treatment and/or test results in diabetic clinics.

In addition, the attendance of different clinics for diagnosis or treatment of NCDs makes adherence to follow-up appointments more tiresome for PLHIV. Patients reported facing difficulty in travelling to and from various appointments at different locations. Therefore, one nurse suggested:

I think it is better to have one point service, i.e., it is better if we integrate HIV care with comorbid conditions at the same clinic. Currently, here we check only their HIV-related needs; if we are able to address their comorbid conditions too, it would be ideal service (HCP10).

b Routine screenings and protocols

The FGD revealed that the lack of geriatric HIV guidelines is a priority issue for health providers as it ‘constitutes the other problems (…) The lack of assessment and need for focus can be solved by protocols, guidelines and standards’ (FGD HCP2, doctor). As there is no specific tool for age-related conditions, health professionals ‘do it by [their] own will’ (HCP5, health officer). Due to the lack of standardisation of geriatric assessments, patients are often diagnosed when the comorbidity is already in a progressed stage.

I could have another condition if I was tested. I knew I was having diabetes only after diagnosis. The nurse was bothered why my CD4 was not increasing while I was on medication. Later I was presented with a complaint of vision problems. (…) After starting antidiabetic drugs I learned my eye condition improved; so that I realised that it was related to diabetes. (P13)

As DM and hypertension were the most common complications in PLHIV, some providers had incorporated screenings for random blood sugar and fasting blood glucose tests in their routine HIV investigations: ‘Before we start medication, we prefer to do a glucose-tolerance test. Depending on their complaint, we do other investigations’ (HCP12, health officer).

Notably, providers varied widely in their risk evaluation of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) and deliria. Providers who consider their older patients at higher risk of HAND screened more often. One provider who did not regard HAND as a significant problem also did not feel the need for screening. Therefore, risk assessment was often found to be a precursor to providers’ response strategies.

Factors affecting healthcare access and quality

Organisational capacity

Providers in the FGD confirmed that system barriers were impeding their care practices as, for example, proper diagnostics or NCD medicines are often missing. While most patients were satisfied with the supply of HIV drugs, many encountered a challenge in accessing NARC drugs in the region: ‘They [health providers] say to us you are diagnosed with hypertension or DM thus go and buy medications. Currently it is becoming very difficult to get the medications for our comorbid conditions. We need an urgent solution for this problem’ (FGD P1).

b Economic constraints

A recurring theme in patient and provider interviews was the affordability of proper care. Providers felt discouraged when available services could not be used due to their unaffordability. For example, a doctor (HCP8) stated that ‘A single sugar measurement is 20 Birr. 20 Birr is high. It is too much for the government hospital’. Similarly, the patients’ financial status made it often impossible for providers to deliver optimal care. As stated by a doctor (HCP3): ‘The major problem is not the absence of the investigation. The major problem is the economic situation of the patient. They cannot afford it’.

Patients reported having difficulties not only accessing NARC medications but also being able to pay for them. In addition, PLHIV perceived economic limitations and the ‘Ethiopian lifestyle’ among the main barriers to practising professional counselling. Twelve out of fifteen could not practice dietary recommendations due to financial difficulties: ‘Our diet system is not good. So, when this is combined with HIV and comorbidities, it is so difficult to cope up with the condition. Economic status is a bottleneck for diet changes’ (FGD P4).

Focus group discussion validation

captures the key findings on the perceived risks and challenges of ageing with HIV, respectively, for providers and patients. The left side entails all the challenges that were raised during the individual interviews. This sum-up was narrowed down to five key issues in the FGD, which are displayed on the right side of the Diamond.

Patients prioritised the following challenges: lack of awareness; financial difficulties; coping with HIV and NARC simultaneously; inadequate training on how to manage their diseases; and seeking support. Four of the five patients raised the lack of awareness about the risk of NARC as their top priority and argued that the government must find a solution to this. In addition, financial difficulties and difficulties of addressing HIV and NARC were emphasised by all five participants; as one PLHIV put it: ‘With my current economic status, my big challenge and priority is to get medications for my comorbid conditions: diabetes, hypertension. Its price is increasing from day to day while our economy is falling, thus I can't cope-up with the condition’ (FGD P2). During individual interviews, patients repeatedly argued that stigma greatly influenced their ability to seek support. Seeking support was raised as a top priority during the FGD; however, most patients no longer perceived stigma as a priority for all their problems: ‘During the time I was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, about 18 years back it was a primary priority area, but currently the awareness about HIV by the community is improved so that people already understand one can live almost as another healthy individual as long as there is medication’ (FGD P4).

Providers placed emphasis on: the lack of awareness; lack of proper NCD modalities; healthcare focus limited to HIV; the need for blended care; and a missing separate unit for geriatric patients. Every provider ranked the lack of protocols and guidelines, as part improper NCD modalities, amongst their top priorities ‘because this constitutes the other problems. For example blended care: if they have a guideline to separate the patients or if they have a guideline to treat older patients, that will help the other problems’ (FGD HCP3, doctor). Although organisational barriers were widely mentioned during the individual interviews, two out of three providers in the FGD did not include this challenge in their Top Five list, as ‘even without resources you can do a lot. We have the set-up, we have the clinic, we have clinicians, nurses. We can train them easily. No big need of resources’ (FGD HCP1, doctor). Doctors indicate to be willing to provide NARC- and geriatric-specific care. However, the strict adherence to traditional methods of care which are embedded in routine care strategies, are believed to hinder a paradigm shift in change of focus.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the contemporary challenges of HIV care for an ageing population with an increasing burden of NARCs. The research draws on a systematic qualitative inquiry that investigates with qualitative interviews. The framework used for this research helps to narrow and confirm key challenges to provide policy makers a roadmap of what to address. This study revealed four key findings. Firstly, there is a need among both providers and patients for more information and counselling on the risk of NARCs and its relation to HIV management. While providers seek to provide the best possible and available care to their patients, they acknowledge the lack of guidance in managing NARCs to their patients. Secondly, the HIV-centred approach of current health systems in Ethiopia inhibits healthcare professionals from focusing on co-occurring disease trends. Although living with HIV is becoming more manageable, patients struggle with the increasing burden of NARCs for which they are very worried. Thirdly, participants highlighted the need for a blended healthcare system in which NARCs and HIV are managed simultaneously in an integrative health system, in which various specialists work together instead of in isolation. Lastly, participants expressed to face financial constraints that limit them from managing their health status appropriately.

A common recurrent theme for both providers and patients was the lack of awareness of risk of NARCs. Solomon et al. (Solomon et al., Citation2013) described patients’ uncertainty about whether NARCs were due to HIV, ageing, or ART; a topic that also came up in our research. Furthermore, previous studies have found that the lack of perception of patients about the risk of NARC is accentuated by poor training to self-manage their diseases (Areri et al., Citation2020; Greene et al., Citation2018). In the study by Greene and colleagues (Greene et al., Citation2018), participants not only emphasised this issue, but expressed a desire to understand more about HIV and the problems of ageing in general. In this study, providers noted the lack of awareness about the importance of screening among themselves and their colleagues. Generally, training and mentorship on the importance of screening and management of NCD is still limited in lower resource settings (Abboah-Offei et al., Citation2019; Bosire et al., Citation2021; Kemp et al., Citation2018; Patel et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the development of supportive tools and training of health workers in screening NARCs is essential in improving care for multimorbid PLHIV. In addition, and as pointed out by health providers themselves, it becomes increasingly important to incorporate training in NARCs in the curricula of health professionals.

The lack of awareness about the risk of NARCs is exacerbated by the HIV-centred approach of current care systems. Ahmad and colleagues (Ahmad et al., Citation2020) demonstrate the significant shortcomings of the traditional approach to understanding the issues of ageing with HIV. The authors state that current systems are disease-centred and focus on the patient's health deficits at a progressive stage where little can be done to prevent decline in function. In this study, providers and patients noted that healthcare delivery models have not shifted in line with the increasing prevalence of NARCs. While in our study, providers were primarily concerned with managing patients’ HIV status, PLHIV themselves were especially concerned about their NARCs. While highly multidisciplinary clinics are already established in many high-income countries, HIV treatment centres in resource-limited countries are often only built as stand-alone programmes (Guaraldi & Palella, Citation2017). Hence, these centres can bring forth the biggest change in developing improved care programmes that are focused on both HIV and NARCs.

As suggested by Safreed-Harmon and colleagues (Safreed-Harmon et al., Citation2019), the shift in the HIV field must be considered in the light of programmatic efforts and policies that are supportive for healthy ageing. In accordance, Aids2031Footnote1 has emphasised the importance of health system transformation in the response from ‘crisis management to sustained strategic response’ (Larson et al., Citation2011; Negin et al., Citation2012). Therefore, the integration of NARC-specific care into HIV services should be accompanied by a scale-up in staff, training of staff, and specific geriatric wards, so that providers are sustained in their care practices.

In addition to the aforementioned, providers and patients indicated a need for a blended healthcare system, in which both HIV status, NCDs, and age-related needs are addressed as a whole instead of separate diseases. This would also enhance the overview when prescribing drugs and therefore avoid drug–drug interactions. Additionally, incorporating specialists that are both concerned with the NCD, and the HIV status will enhance the continuity of care and stimulate adherence of patients. This is consistent with the existing HIV and ageing literature. Although routine screenings of ageing-related diseases are widely suggested (Alford et al., Citation2019; Cardoso et al., Citation2013; Perfect et al., Citation2019), it is often not integrated in current care practices. HIV programmes and NCD programmes are vertical in many low-resource settings (Mitambo et al., Citation2017). Therefore, providers often miss proper diagnoses and must deal with age-related complications in a progressed stage. As the cohort of PLHIV is ageing, new screening protocols are needed that consider risk group identification, screening, and management of comorbid conditions. As stated by Erlandson and Karris (Erlandson & Karris, Citation2019), screening also has the potential to result in polypharmacy. In this study, providers mainly feared multi-morbid management for its complexity in prescribing the right medication. Therefore, further research is needed to identify concrete pathways for blending NCD services into existing HIV services; thereby approaching patients as a whole instead of as a collection of diseases. This requires capacity building on chronic care management under advanced models (e.g. Integrated Chronic Disease Model) which ensure that strategies and guidelines on the integration of NARCs are standardised across different sectors and facilities.

Many patients revealed to be financially constrained when managing their comorbidities and HIV infection. Although HIV medications are nowadays offered at no cost, PLHIV who require (primary) care services for chronic diseases are expected to cover these additional services (Kiplagat et al., Citation2019). To ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages (SDG3)’, it is of paramount importance to achieve ‘access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines (target 3.8)’ (United Nations, Citation2015). The potential to achieve these goals lies in the investment in universal health coverage by international, national, and sub-national donors. The delivering of accessible NCD medicines requires earmarked funds in national budgets (Kintu et al., Citation2020). As suggested by Hogerzeil and colleagues, low- and middle-income countries also need to increase mobilisation of domestic resources to provide access to treatment for those who cannot afford (Hogerzeil et al., Citation2013). In addition to the costs of NCD medication, the availability of NCD modalities, screening tools and treatment options are also hampered by economic constraints. Our findings are in line with earlier investigations (Justice, Citation2010; Knight et al., Citation2018; Laurent Santye Schatz et al., Citation2017; Power et al., Citation2022) conducted in the low-resource context, indicating the ongoing struggle faced by older adults in managing NARC in addition to HIV. The costs of transportation and distance to the facility have been commonly cited as barriers to accessing HIV care services among older PLHIV (Knight et al., Citation2018; Schatz et al., Citation2017). These barriers are exacerbated by the persistent verticalisation (Zakumumpa et al., Citation2018) in the provision of HIV care. Previous studies have proposed to consider NARC in the provision of optimal patient-centred treatment for HIV-infected older people (Guaraldi & Milic, Citation2019; May & Finch, Citation2021). Integrating chronic diseases into HIV management can significantly reduce costs and time, and therefore improve ongoing participation in the care of older people. In addition, it could address the issue of stigma, where care is provided by a single provider of care to all those infected and not infected with HIV.

The findings of this research must be considered in the light of its limitations. Consistent with the qualitative and exploratory nature of this study, the study sample was small and selective. In addition, the sampling strategy was bound to the availability of participants in their ART clinic and the time of recruitment. While the research team attempted to recruit a diverse sample of participants and solicit multiple responses and perspectives from a variety of patients and providers, we have likely missed to include patients and providers who would have added their unique experiences on the topic. Potential bias may have occurred as respondents were found through the clinics, which could have attracted more motivated and engaged health care providers. Moreover, part of the research team has committed to the English version of the transcript and not the Amharic version, which may not capture sensitive or culturally specific findings. This concern was addressed by having the other part of the research team review the findings. In addition, this diverse sample is limited to Southern Ethiopia which may limit the generalisability of findings to other geographic areas. Nevertheless, findings may be applicable to various low-resource settings that follow the same epidemiological and demographic transition as Southern Ethiopia (Areri et al., Citation2020). Although high income countries may be ahead in their shift towards integrated NCD care for PLHIV in their health settings, lower-resource settings are still struggling in their approach to tackle the emerging challenges of contemporary health transitions (Shao & Williamson, Citation2011).

Conclusion

Our study represents one of the first efforts to characterise the complex challenges of ageing with HIV in Ethiopia and, more importantly, outside of a high-income country setting. For many years, older PLHIV have been a neglected group experiencing numerous health problems yet have received little research attention. The combined perspective of patients and providers on the increasing burden of multimorbidity in ageing PLHIV has highlighted the importance of improving geriatric care in HIV settings. To sustain the global achievements in HIV care, traditional care models must adapt to the emerging challenges of a ‘greying’ and growing population. Patients and their healthcare providers need to better communicate and understand the challenges they face and possible acceptable solutions, as they both face their own challenges with little notice of each other's experience. By entailing the NPT framework and the Diamond Model, this research bridges the gap between barriers and interventions to improved chronic care delivery in HIV settings. The next step is to expand the scale and scope of integrated geriatric services and allocate new funding sources that sustain a chronic care model in transition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Aids2031 is a group established by CitationUNAIDS that charts the required actions for addressing the trajectory of the HIV epidemic.

References

- Abboah-Offei, M., Bristowe, K., Koffman, J., Vanderpuye-Donton, N. A., Ansa, G., Abas, M., & Higginson, I., Harding, R. (2019). How can we achieve person-centred care for people living with HIV/AIDS? A qualitative interview study with healthcare professionals and patients in Ghana. AIDS Care, 32(12), 1479–1488 https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1698708

- Ahmad, A., Neelamegam, M., & Rajasuriar, R. (2020). Ageing with HIV: Health implications and evolving care needs. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(9), 1–3 . https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25621

- Alford, K., Banerjee, S., Nixon, E., O’Brien, C., Pounds, O., Butler, A., Elphick, C., Henshaw , P., Anderson, S., & Vera, J. H. (2019). Assessment and management of HIV-associated cognitive impairment: Experience from a multidisciplinary memory service for people living with HIV. Brain Sciences, 9(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020037

- Areri, H., Marshall, A., & Harvey, G. (2020). Exploring self-management of adults living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in North-West Ethiopia: Qualitative study. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 12, 809–820. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S287562

- Boffito, M., Ryom, L., Spinner, C., Martinez, E., Behrens, G., Rockstroh, J., Hohenauer, J., Lacombe, K., Psichogyiou, M., Voith, N., Mallon, P., Branco, T., Svedhem, V., & dÁrminio Monforte, A. (2020). Clinical management of ageing people living with HIV in Europe: The view of the care providers. Infection, 48(4), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01406-7

- Bosire, E., Mendenhall, E., Norris, S., & Goudge, J. (2020). Patient-centred care for patients with diabetes and HIV at a public tertiary hospital in South Africa: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(9), 534. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.65

- Bosire, E., Norris, S., Goudge, J., & Mendenhall, E. (2021). Pathways to care for patients with type 2 diabetes and HIV/AIDS comorbidities in Soweto. South Africa: An Ethnographic Study. Global Health: Science and Practice, 9(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00104

- Brew, B., & Cysique, L. (2017). Does HIV prematurely age the brain? The Lancet HIV, 4(9), e380–e381. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30108-X

- Cardoso, S., Torres, T., Santini-Oliveira, M., Marins, L., Veloso, V., & Grinsztejn, B. (2013). Aging with HIV: A practical review. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 17(4), 464–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2012.11.007

- Cysique, L., & Brew, B. (2019). Vascular cognitive impairment and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: A new paradigm. Journal of NeuroVirology, 25(5), 710–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-018-0706-5

- Deeks, S., Lewin, S., & Havlir, D. (2013). The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. The Lancet, 382(9903), 1525–1533. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7

- Deribew, A., Biadgilign, S., Berhanu, D., Defar, A., Deribe, K., Tekle, E., Asheber, T., & Dejene, T. (2018). Capacity of health facilities for diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3347-8

- Eisinger, R., & Fauci, A. (2018). Ending the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 24(3), 413–416. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2403.171797

- Emlet, C., & Poindexter, C. (2004). Unserved, unseen, and unheard: Integrating programs for HIV-infected and HIV-affected older adults. Health & Social Work, 29(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/29.2.86

- Erlandson, K., & Karris, M. (2019). HIV and aging. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 33(3), 769–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2019.04.005

- Erwin, K., & Krishnan, J. (2016). Redesigning healthcare to fit with people. BMJ, 354, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4536

- Falutz, J. (2020). Frailty in people living with HIV. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 17(3), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-020-00494-2

- Fauci, A., & Lane, H. (2020). Four decades of HIV/AIDS — much accomplished, much to Do. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1916753

- Girum, T., Wasie, A., & Worku, A. (2018). Trend of HIV/AIDS for the last 26 years and predicting achievement of the 90–90-90 HIV prevention targets by 2020 in Ethiopia: A time series analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3214-6

- Godongwana, M., De Wet-Billings, N., & Milovanovic, M. (2021). The comorbidity of HIV, hypertension and diabetes: A qualitative study exploring the challenges faced by healthcare providers and patients in selected urban and rural health facilities where the ICDM model is implemented in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06670-3

- Greene, M., Tan, J., Weiser, S., Christopoulos, K., Shiels, M., O’Hollaren, A., Mureithi, E., Meissner, L., Havlir, D., & Gandhi, M. (2018). Patient and provider perceptions of a comprehensive care program for HIV-positive adults over 50 years of age: The formation of the golden compass HIV and aging care program in San Francisco. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208486

- Guaraldi, G., & Milic, J. (2019). The interplay between frailty and intrinsic capacity in aging and HIV infection. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 35(11-12), 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2019.0157

- Guaraldi, G., & Palella, F. (2017). Clinical implications of aging with HIV infection. Aids (london, England), 31(Supplement 2), S129–S135. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001478

- Harling, G., Payne, C., Davies, J., Gomez-Olive, F., Kahn, K., Manderson, L., Mateen, F. J., Tollman, S. M., & Witham, M. D. (2019). Impairment in activities of daily living, care receipt, and unmet needs in a middle-aged and older rural South African population: Findings from the HAALSI study. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(5-6), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264318821220

- Harris, T., Rabkin, M., & El-Sadr, W. (2018). Achieving the fourth 90. Aids (London, England), 32(12), 1563–1569. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001870

- Hawkins, J., Madden, K., Fletcher, A., Midgley, L., Grant, A., Cox, G., Moore, L., Campbell, R., Murphy, S., Bonell, C., & White, J. (2017). Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4695-8

- Hogerzeil, H., Liberman, J., Wirtz, V., Kishore, S., Selvaraj, S., Kiddell-Monroe, R., Mwangi-Powell, F. N., & Von Schoen-Angerer, T. (2013). Promotion of access to essential medicines for non-communicable diseases: Practical implications of the UN political declaration. The Lancet, 381(9867), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62128-X

- IDEO.org. Resources. The field guide to human-centred design. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from http://www.designkit.org//resources/1.

- Justice, A. (2010). HIV and aging: Time for a new paradigm. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 7(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-010-0041-9

- Kemp, C., Weiner, B., Sherr, K., Kupfer, L., Cherutich, P., Wilson, D., Geng, E. H., Wasserheit, J. (2018). Implementation science for integration of HIV and non-communicable disease services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Aids (london, England), 32(Supplement 1), S93–S105. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001897

- Kintu, A., Sando, D., Okello, S., Mutungi, G., Guwatudde, D., Menzies, N., Danaei, G., & Verguet, S. (2020). Integrating care for non-communicable diseases into routine HIV services: Key considerations for policy design in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(S1), e25508. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25508

- Kiplagat, J., Mwangi, A., Chasela, C., & Huschke, S. (2019). Challenges with seeking HIV care services: Perspectives of older adults infected with HIV in western Kenya. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7283-2

- Knight, L., Schatz, E., & Mukumbang, F. (2018). “I attend at Vanguard and I attend here as well”: barriers to accessing healthcare services among older South Africans with HIV and non-communicable diseases. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0863-4

- Larson, H., Bertozzi, S., & Piot, P. (2011). Redesigning the AIDS response for long-term impact. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89(11), 846–852. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.087114

- Laurent Santye, A. Managing HIV in the aging population. Pharmacy Times. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/managing-hiv-in-the-aging-population.

- Levett, T., Alford, K., Roberts, J., Adler, Z., Wright, J., & Vera, J. (2020). Evaluation of a combined HIV and geriatrics clinic for older people living with HIV: The Silver Clinic in Brighton, UK. Geriatrics, 5(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics5040081

- Linsk, N. L., Fowler, J. P., & Klein, S. J. (2003). HIV/AIDS prevention and care services and services for the aging. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 33, S243-S250. https://doi.org/10.1097/00126334-200306012-00025

- May, C., & Finch, T. (2021). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554.

- McGettrick, P., Barco, E., & Mallon, P. (2018). Ageing with HIV. Healthcare, 6(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6010017

- Melles, M., Albayrak, A., & Goossens, R. (2020). Innovating health care: Key characteristics of human-centered design. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 33(Supplement_1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa127

- Mitambo, C., Khan, S., Matanje-Mwagomba, B., Kachimanga, C., Wroe, E., Segula, D., Amberbir, A., Garone, D., Malik, P. R. A., Gondwe, A., & Berman, J. (2017). Improving the screening and treatment of hypertension in people living with HIV: An evidence-based policy brief by Malawi’s Knowledge Translation Platform. Malawi Medical Journal, 29(2), 224. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v29i2.27

- Negin, J., Bärnighausen, T., Lundgren, J., & Mills, E. (2012). Aging with HIV in Africa. Aids (London, England), 26(Supplement S1), S1–S5. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283560f54

- Negredo, E., Back, D., Blanco, J., Blanco, J., Erlandson, K., Garolera, M., Guaraldi, G., Mallon, P., Moltó, J., Antonio Serra, J., & Clotet, B. (2017). Aging in HIV-infected subjects: A new scenario and a new view. BioMed Research International, 2017, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5897298

- Osakunor, D., Sengeh, D., & Mutapi, F. (2018). Coinfections and comorbidities in African health systems: At the interface of infectious and noninfectious diseases. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 12(9), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006711

- Patel, P., Speight, C., Maida, A., Loustalot, F., Giles, D., Phiri, S., Gupta, S., & Raghunathan, P. (2018). Integrating HIV and hypertension management in low-resource settings: Lessons from Malawi. PLOS Medicine, 15(3), e1002523. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002523

- Perfect, C., Wilson, L., Wohl, D., Okeke, N., Sangarlangkarn, A., & Tolleson-Rinehart, S. (2019). Improving care for older adults with HIV: Identifying provider preferences and priorities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(4), 891–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16296

- Power, L., Bell, M., & Freemantle, I. (2022). A national study of ageing and HIV (50 Plus). Retrieved January 10, 2023, from http://www.jrf.org.uk/.

- Rosenfeld, D., Ridge, D., & Lob, G. (2014). Vital scientific puzzle or lived uncertainty? Professional and lived approaches to the uncertainties of ageing with HIV. Health Sociology Review, 23(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2014.23.1.20

- Sabin, C., & Reiss, P. (2017). Epidemiology of ageing with HIV. Aids (london, England), 31(Supplement 2), S121–S128. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001374

- Safreed-Harmon, K., Anderson, J., Azzopardi-Muscat, N., Behrens, G., d’Arminio Monforte, A., Davidovich, U., Del Almo, J., Kall, M., Noori, T., Porter, K., & Lazarus, J. V. (2019). Reorienting health systems to care for people with HIV beyond viral suppression. The Lancet HIV, 6(12), e869–e877. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30334-0

- Schatz, E., Seeley, J., Negin, J., & Mugisha, J. (2017). They ‘don’t cure old age’: Older Ugandans’ delays to health-care access. Ageing and Society, 38(11), 2197–2217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17000502

- Shao, Y., & Williamson, C. (2011). The HIV-1 epidemic: Low- to middle-income countries. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2(3), a007187–a007187. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a007187

- Siedner, M. (2017). Aging, health, and quality of life for older people living With HIV in Sub-saharan Africa: A review and proposed conceptual framework. Journal of Aging and Health, 31(1), 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317724549

- Solomon, P., O’Brien, K., Wilkins, S., & Gervais, N. (2013). Aging with HIV and disability: The role of uncertainty. AIDS Care, 26(2), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.811209

- Sylla, L., Evans, D., Taylor, J., Gilbertson, A., Palm, D., Auerbach, J. D, & Dubé, K. (2018). If We build It, will they come? Perceptions of HIV cure-related research by people living with HIV in four U.S. Cities: A qualitative focus group study. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 34(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2017.0178

- Tiruneh, B., McLelland, G., & Plummer, V. (2020). National healthcare system development of Ethiopia: A systematic narrative review. Hospital Topics, 98(2), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00185868.2020.1750323

- Trickey, A., May, M., Vehreschild, J., Obel, N., Gill, M., Crane, H. M., Boesecke, C., Patterson, S., Grabar, S., Cazanave, C., Cavassini, M., Shepherd, L., d'Arminio Monforte, A., van Sighem, A., Saag, M., Lampe, F., Hernando, V., Montero, M., Zangerle, R., . . . Justice, A. C. (2017). Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet HIV, 4(8), e349–e356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8

- Tsekleves, E., & Cooper, R. (2017). Emerging trends and the Way forward in design in healthcare: An expert’s perspective. The Design Journal, 20(sup1), S2258–S2272. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352742

- UNAIDS. (2021) Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet [Internet]. Unaids.org. 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021, from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. UN Publishing.

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2021). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405.

- Walker-Bone, K., Doherty, E., Sanyal, K., & Churchill, D. (2016). Assessment and management of musculoskeletal disorders among patients living with HIV. Rheumatology (Oxford), 56(10), 1648–1661. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew418

- Willig, A., & Overton, E. (2016). Metabolic complications and glucose metabolism in HIV infection: A review of the evidence. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 13(5), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-016-0330-z

- Zakumumpa, H., Rujumba, J., Kwiringira, J., Kiplagat, J., Namulema, E., & Muganzi, A. (2018). Understanding the persistence of vertical (stand-alone) HIV clinics in the health system in Uganda: A qualitative synthesis of patient and provider perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3500-4