ABSTRACT

The hyper-neoliberal era has seen the collapse of the ethos of life and the formation of a civilisation of extreme greed. In this global context, the pre-eminence of a technologically endowed but epistemologically and ethically misguided form of science has contributed to forms of ‘scientific illiteracy’ and strategies of planned ignorance that nourish a neo-conservative form of governance. The challenge of transforming the paradigm of bioethics and the right to health beyond the biomedical horizon is an urgent priority. Building on the strengths of a social determination approach and a meta-critical methodology and rooted in critical epidemiology, this essay proposes powerful tools for a radical shift in thought and action linked to rights and ethics. Together, medicine, public health, and collective health provide a path forward to reform ethics and advance the rights of humans and nature.

Hyper-neoliberalism: The collapse of the ethos of life in the twenty-first century and the civilisation of greed

How do we evaluate the state of life, ethics, justice, and rights in today’s world? We live in the most dangerous and aggressive historical period of hyper-neoliberal capitalism.Footnote1 Unhealthy structural processes incompatible with life and health are being globally accelerated and are woven together with an exponential growth of inequity. In the Global South, this is an era of the dismantling of human rights. This brutal process has led to the elimination of policies focused on the common good and has destroyed the last vestiges of the social contract.

In the twenty-first century, social reproduction is closely tied to prioritising an absurd concentration of private wealth. The logic of accelerated hoarding is reproduced, installing rapid, highly specialised, and continuous large-scale processes that increase the differential earnings and profit of large corporations leaving small – and medium-sized businesses to absorb production costs, bypassing their rights. It is the regrettable eclosion of what one prestigious economist describes as ‘the curse of business gigantism’ or ‘dis-economies of scale,’ ‘where the internal greed of corporations becomes structural’ (Wu, Citation2020, pp. 10–11).

The fourth industrial revolution of capitalism drove the rapid development of the forces of production, accelerating productivism through an explosive convergence of new technologies (Schwab, Citation2016). Robotics, nanotechnology, biotechnology, ‘big data’ operations, hypermedia, and artificial intelligence have unfortunately become tools of profit without regulation and precaution, constituting a powerful industrial arsenal for increasing said vertiginous extraction rate (Ribeiro, Citation2016). This is often paired with social regulation by algorithmic governance (Ferrante, Citation2021), which perpetuates consumer behaviours and political and cultural affinities, as well as a racist distribution of information and services (Obermeyer et al., Citation2019).

Thus, in today’s global scenario, it is no surprise that we are seeing the exponential growth of the mechanisms that reproduce inequity. Historical measurements of global inequity data show that the gap between income from private capital (r) and the income and value of production (g) that existed throughout the twentieth century is expanding (r > g) even further during this millennium (Piketty, Citation2022). That multiplication of social inequity is paired with an ethos of greed, the increasing loss of rights and sovereign life, and even mass social and biological insecurity that more intensely affects the oppressed social classes, genders, and ethnic communities that survive in neoliberal cities and shape the new neoliberal rural space.

Looking at the configuration of social spaces, Lefebvre (Citation1991) determined that capitalism 4.0 has transformed both cities and the rural sector, prioritising the spatial convenience of major urban real estate and industrial and commercial capital. This also impacts the infrastructures and flows of rural life. The dialectic movement of space produced-productive space is thus created in which the spaces produced by capitalism construct and reproduce inequity.

In the context of twenty-first-century extractivism, we must offer a perspective based on rights, ethics, and health on digital productive structures that provide information, monitor real user movements, and serve as an intermediary in satisfying their consumption needs (Subirats, Citation2019). It is not the shift from an economy of production to one of information, as some argue, but from the 3.0 level extraction economy to a 4.0 economy where extraction still occurs. In this new economy, information, along with other technologies, is critical to serving the acceleration of production but does not replace the essential framework of the comprehensive capital system. Technology 4.0 coordinates with previous productive and technological modes to accelerate extraction.

In the eye of this hurricane, where humanity is lodged in a failed and voracious trance, the expansion and diversification of extractivism stand out. Extraction is maximised as a logic of accumulation propagated to cover unprecedented amounts of space and new production technologies. Even what is called post-work turns entrepreneurial citizens into workers that continue to produce from digital platforms. The cycle consists of a quick increase in income from capital at the expense of all types of rights. It is executed by extracting merchandise from various social spaces and territories, reducing production costs, and selling an infinite set of new products to condition high demand.

Furthermore, this dangerously unbridled productivist globalisation is a matter that directly concerns new discussions about law, rights, ethics, and health. In that logic of infinite accumulation, the sacred code and language of individual rights and the ethics of ‘development’ are invoked to justify and defend supposed progress. They are also used to subordinate advocacy against the ‘secondary effects’ of capitalism that dismantle the common good (Breilh, Citation2021a). Thus, in this context, we must create a new framework to discuss rights, ethics, and health that has not been co-opted by neoliberalism.

Mode of thinking, power, and ethics: Strategic ignorance, scientific illiteracy, and neo-conservative governance

Before analysing the interpretive and logical challenges that we face when rethinking rights and ethics, we must complement our critical analysis of the historical context with a reflection on two forms of containment and invisibilization of critical theory: planned scientific ignorance and scientific illiteracy.

The researchers who are the victims of this control are subject to systematic and ongoing pressure wielded by the powerful elites over science and universities. Economic and political powers over science, such as the coercion of companies, can take minor, surreptitious forms. It can also, through the collusion of representatives of public power and legal teams, become a platform with enough resources to fund dissuasive studies, generate results that support their positions, or even take the form of violent operations, as has been broadly documented in the analysis of emblematic cases from the previous century (including, for example, tobacco, gas, and genetically engineered food interests) (Michaels, Citation2008).

The construction of concepts like ‘scientific strategic ignorance’ and ‘scientific illiteracy’ emerged in response to this scenario, with a historical accumulation of a voluminous and vastly documented dossier. Furthermore, the critical thought developed around this concept has shown how notable cases of the systematic application of ‘science against science’ were planned and consummated, working through intentional and ‘planned ignorance.’ The problem has been so significant that it led to the creation of a formal programme of study of planned ignorance or agnotology at Stanford University. The programme generated a valuable collection of publications that show that ignorance is more than a simple absence of knowledge. Instead, it uses scientific knowledge to bias the horizon of scientific visibility and focuses exclusively on the facts that power designates as worthy of being known (Proctor & Schiebinger, Citation2008). One result of that concealment, that academic sectors positioned in the Cartesian method reproduce, is what Harding has termed scientific illiteracy (Harding, Citation1993). These forms of ignorance and illiteracy benefit those in power, often based in forces of capitalism and class struggle, racism, sexism, gender and coloniality.

One characteristic of higher education, especially in the life sciences, is the overwhelming dominance of the Cartesian paradigm in programmes of study. This paradigm reproduces the theoretical, methodological, praxeological, and axiological foundations of inductive empirical linear thought, rather than creating space for critical and transformative thought. In a clarifying essay on the topic, David Sackett analysed the regressive role of academic institutions and their obedient technocracy regarding transformative thought in the British Medical Journal under the title ‘The Sins of Expertness and a Proposal for Redemption’ (Sackett, Citation2000).

In previous studies, we offer an in-depth explanation of the cognitive obstacles of Cartesian science (Breilh, Citation1977/2010, Citation2003) which illustrate our thesis regarding the close connection between the Cartesian paradigm and scientific illiteracy, we will summarise a few key arguments.

Cartesian research describes the surface of problems without getting to their roots. It reports on partial evidence without articulating it with the social matrix, thus placing a veil over the deep reality that immobilizes researchers in the face of the theses of real transformation and condemns them to functionalist pragmatism. In every field and draped in different disciplinary clothes, Cartesian science works with isolated factors of the issue without showing their relationship to the social reproduction of capital and the structural processes that generate them. This is the case because that form of thought levels and converts a dynamic and complex reality into static fragments of a disarticulated world.

First, the construction of strategic ignorance and scientific illiteracy on health, beyond the biomedical horizon of training and practices, constitute platforms of governance that serve the interests of the powerful and function to limit health equity and the right to health for all.

Second, the institutional contexts of scientific ignorance are characterised by an ethical collapse of policy and management. Politicians and public agents in institutional environments, in both material and ethical crises, commonly ignore substantial proven solutions generated by collectives that push for critical science. The actual content of complex problems is hollowed, the depth of analysis related to prevention is lost, and the beneficial use of public funds passes to companies or research that upholds existing power structures. This collapse of the ethics of prevention has been demonstrated in magnificent essays like Susana Vidal’s analysis of SARS-CoV2 (S. M. Vidal, Citation2022).

Third, higher education, particularly graduate studies in the Global South, reproduce and amplify an academic system subject to a clear epistemological and intellectual-cultural dependency on the hegemonic models of the conservative North. This system includes: an ongoing epistemicide of other forms of thought and knowledge; a persistent reproduction of the technocratic ethos (the Cartesian approach to and treatment of policies); and an international dismissal of plans to address the complex social and epidemiological crisis of neoliberal societies.

Fourth, the circumstances described above occur in concert with a loss of terrain in consolidating and making progress on equal rights. This stalling of justiciability halts the advance of laws and rules that must be introduced in response to the conditions of an era of accelerated threats, increasing inequality, and the derailing and emptying of institutional and political ethos (Breilh, Citation2021a).

Below, I offer some proposals for rethinking pathways to a new paradigm that can transform notions of objectivity, offering new epistemological and ethical foundations for an in-depth reformation of the right to health rooted in emancipatory ethics. In order to do so, we must overcome scientific inertia and, instead, activate a proactive, empowered, comprehensive thought on the right to health that goes beyond the barriers of strategic ignorance and the Cartesian logic that reduces justiciability. In doing so, we can turn laws, rules, and precepts of law into functional pieces of the ethos and governance instead of what power requires to reproduce its hegemony.

Social determination and the four S’s of the ethics of life

The paradigm of bioethics beyond the biomedical horizon

Thinking about ethics should not be an abstract academic theorisation. Instead, it should be a reflection dialectically connected to the common good and serving the strategic needs that diverse collectives identify in specific social spaces.

As such, bioethics implies a process that is not limited to the biomedical gaze in individual care scenarios, but reaches the complex, broader process of the ethics of life in general, and specifically the ethics of collective health. The abundant bibliography on bioethics is a fact that we should take up in a dialectic sense. On the one hand, it is good that we have accumulated reflection and experience. On the other, much of that literature has a Cartesian-functional theoretical-methodological bias that negatively influences academic spaces.

In capitalist society, economic-colonial-patriarchal power has historically invested vast resources to position the functional science that leads us to understand bioethics as an essentially individual and medical challenge. This reductionist paradigm understands health as a fragmented whole decontextualised from empirically perceived problems and measured as variables separate from social relations (material and symbolic) and the determination of power (economic-political, ethno-cultural, and gender).

Thus, there is a need to redefine ethics and their rights. It is diverse collectives who must redefine it, determining:

What do the opportunities to live a good, fair, and healthy life depend on?

What relationships does society maintain with nature through working and living that affect ecosystemic life and justice and condition the ecological ethos of our societies?

What relationships emerge between various social and cultural groups that condition access to good and fair living, and limit or drive the sovereign and effective development of ethics?

How must all of the above serve as the basis for the coherent and emancipatory articulation of a struggle? How must this mark the role of ethics, rights, and law?

These questions require moving towards a radically different form of thought that engages the complexity of the problem, adheres to diverse values and commitments, rethinks the plurality of the political, and takes distance from the unilateral perspectives of an illuminist vanguard.

Assuming that bioethical work and rights formulation is a collective product, we must focus on the challenge of understanding bioethics as a process developed in intercultural terms. This shift involves understanding that the politics of bioethics are ‘not limited to giving form and direction to a single set of social relations and economic and social life structures, but to uneven or diverse sets of social relationships that have generally overlapped asymmetrically under relationships of discrimination, exploitation, and domination’ (Tapia, Citation2013, p. 97).

It should come as no surprise that bioethics has been, at its origins, framed primarily by the terrain of human biology, the clinic, and survival, ignoring essential aspects of a comprehensive perspective (Pacheco, Citation2022; Potter, Citation1970). In academic spaces heavily conditioned by biological determinism and Cartesian logic, actual processes disappear as the profound subsumption of the biological individual in the social or the collective determination of personal styles of livingFootnote1 and values. This perspective sets aside the determinative fact that those personal daily itineraries are only possible or performed in the context of collectively structured modes of living and social relations that mark protective or destructive patterns. Collectively, we have by and large stopped looking at processes deeply linked to the modes and ethics of living, determined by classist, racist, and patriarchal relations and distributed under profound inequity in our societies.

Social determination and the reform of rights and ethics: Rethinking justiciability

Thinking through the challenges to health within neoliberal systems and the civilisations that underpin them, it is essential to search for an in-depth reform of the law and ethical principles that will contribute to a necessary legal transition.

We can think through that challenge from different perspectives and spaces of enunciation, but I will focus on the horizon of visibility and the tools of Latin American critical epidemiology. This horizon presents a clear identification and complementarity with the ‘ecology of knowledge’ posed by one of the most important thinkers of epistemologies of the South: Boaventura Santos (De Sousa Santos, Citation2014).

The issue of the right to health is vast, and it is impossible to provide a comprehensive analysis in this brief article. As such, one cannot fully cover the contributions of diverse nuclei of academics and researchers from South America from the Latin American social medicine/collective health movement (ALAMES). Contributions were forged through many decades of social struggle, and different contexts of reflection and cross-fertilisation led to various emancipatory theses, alternative methodologies, and spaces of contra-hegemonic actions in diverse fields. It is thus necessary to begin our analysis by explaining what we mean by a ‘profound reform’ of justiciability in health and the ethical principles we use to guide it.

A key distinction was posed by Latin American philosopher Bolívar Echeverría when distinguishing between reformism and reform in the process of social transition. Echeverría states that there are two interdependent levels of historical change: changes to social forms– in this case, ethical-legal ones– and changes in the substance that defines the nature of society. Following this potent distinction, I will say that the substance of current law must be subverted to achieve real reform and effective transformation of the right to health. Within the substance of the right to health, we must understand what laws and rules define as justiciable and the depth with which existing legal tools halt or repair the destructive processes that impact health. Inversely, we can focus on the degree to which specific legal tools truly protect the processes of life and caring for it (Breilh, Citation2009). In response to this dilemma, we see that the ethics embodied in a society contribute (or do not) to establishing the difference between reformism and legal reform in health.

Once clarified this difference, we can explain health as a complex process, thinking with critical epidemiology and specifically articulating the category of social determination. In this sense, approaching health as a multidimensional and dialectic process that is socially determined is not limited to replacing the masthead of risk factors with the equally Cartesian notion of social determinants (i.e. ‘causes of causes’). For example, Clark & Leavell's innovative ecosystemic perspective (Clark & Leavell, Citation1965), has a theoretical basis in an empirical ecologism derived from Parsons’ systems approach, reproducing Cartesianism (Parsons, Citation1951). We should go beyond. In order to overcome the Cartesian paradigm, the critical epidemiology that we have proposed works with broadly developed nodal categories (Breilh, Citation1977, Citation1977/2010, Citation2010) that allows us to explain the social determination of health as a complex process:

1. Social reproduction, in critical epidemiology, is the process of the production and distribution of life. In this process, the living subject is objectified in things by producing what has been socially agreed upon as ‘useful’ for equally agreed-upon needs. The consumer, in turn, recreates themself as a subject who accesses said use values. Our society is reproduced through this complex, multidimensional process, the deep foundations of which were laid out by Bolívar Echeverría in his pedagogical explanation of social reproduction, a milestone in graduate training for those of us who had the privilege of being his students in Mexico (Echeverría, Citation1975). In addition to creating use values and exchanging products based on their exchange value, the cultural and political conditions of said process are created, some through underpinning and others through resistance. At the same time, the conditions of society-nature metabolism (discussed below) are established in the corresponding social space. Below, I explain how these conditions reaffirm that harmful social reproduction is exponentially accelerated in hyper-neoliberal society.

When we look at reality in this context of concatenation and integrated processes, we overcome Cartesian empiricism and stop reducing health to a set of causes and risk factors. Moreover, we look at health rights beyond patients’ biological and psychic individuality, radically reframing the world of health to investigate its determinant substrate.

Thus, social reproduction is the dialectic foundation or matrix that those who fight for health, progress on rights, and socio-bio-ethics should understand. It is the category that explains the ontological complexity of collective health and sustains the effective reformulation of the comprehensive dimension of the justiciable (Harding, Citation1993).

The material basis of this process is comprised of the dialectic relationship between: i) modes of producing and modes of consuming; ii) the specific social space from which they come that, as Lefebvre has explained, is simultaneously socially produced and producing the very same social system that generated it in the first place (Lefebvre, Citation1991); iii) the process of social reproduction generates various embodiments which critical epidemiology studies in order to understand both the protective and destructive facets and expressions of life and health; and iv), finally, the historically determined political and cultural processes contributes to supporting and generating said material basis. As such, the multidimensional, dialectical, historically, and spatially determined character of health and its determination can only be understood from complex thinking.

Social reproduction develops in three dialectically interdependent domains:

The general, broader, and more complex domain corresponds to the logic of accumulation and the hegemonic politics and culture that anchor it. This domain permeates and subsumes the other domains. Depending on the type and conditions of social reproduction, the general conditions of sustainability, sovereignty, solidarity, and comprehensive security (the 4S’s of life and good living) are determined. These are also active processes that participate in the general determination of social reproduction.

The particular domain of the reproduction of social classes is crossed by gender and ethno-cultural relationships whose relationships may involve cooperation or exploitation and domination. The social classes of this particular domain do not constitute a mere empirical aggregate of people who share similar values of individual indicators (i.e. generally, market variables such as income or consumption levels). They are collectives characterised by a similar mode of living that conditions specific exposure and vulnerability patterns. These are clearly differentiated among different classes, gender, and ethno-cultural conditions. Critical epidemiology analyses and evaluates the conditions of the 4S’s in each of those spaces as socially determined embodiments and active processes that participate in the determination of collective health. Patterns of epidemiological exposure and vulnerability are determined in that dialectic. Therefore, the analysis of the components of the right to healthy life is also derived from this particular dimension.

Lastly, there is the individual domain to which the individuals and families of these social classes belong, with their styles of living and personal daily life. These people exist with their bodies, phenotype and genotype, psychic life, and forms of spirituality. Here too, full personal life implies individual conditions of sustainability, freedom (sovereignty), solidarity, and security that develop under the subsumption of the particular conditions of social class, gender, and ethno-cultural conditions, but which also dialectically affect the life of their collectives.

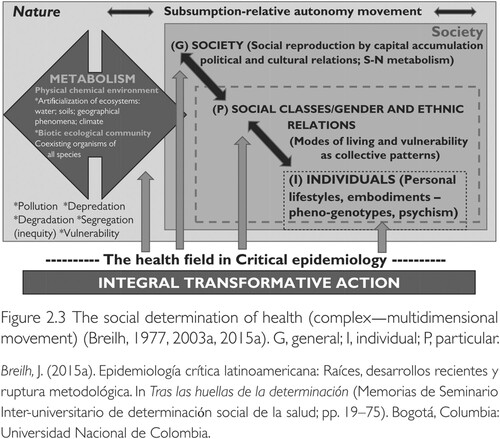

2. Social determination is the mode of becoming that generates the conditions and embodiments of the various dimensions. It is a mode of becoming that produces health processes, within social living that generates the complex dialectic conditioning of health and its corresponding critical processes, with their healthy and protective expressions, as well as unhealthy and destructive ones. The subsumption of the less complex in the more complex -for example, of the individual in the collective or the biological in the social- implies an inherent connection between said phenomena in three domains: general (G), particular (P), and individual (I). In each of these, the society-nature (S-N) metabolism (discussed further below) results from the subsumption of natural and ecosystemic processes within social processes such as production, consumption, and political-cultural relationships, all of which are historically determined. In all of those domains, as I have said, the contradiction between healthy-protective and unhealthy-destructive processes is recreated on an ongoing basis, establishing a mode of becoming that generates embodiments that are essential manifestations of collective health .

Figure 1. Breilh J.2021. Critical epidemiology and the people's health. New York: Oxford University Press, p.96.

The determination category thus refers to the generative power of social processes and their spiral of contradictions. Ontologically speaking, determination provides the foundation for health processes and offers a logic of objective articulation that replaces the linear conjunction of analytical empiricism. In several recent publications, we have insisted on two substantial clarifications: a) the radical difference between the categories of determination and determinism; and b) the substantial theoretical, methodological, and practical differences between the Latin American paradigm of social determination and the paradigm of what is called social determinants of health (Breilh, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Our reading of social determination emerged in alignment with and interrelated with valuable Latin American perspectives offered by scholars such as Naomar Almeida (Almeida-Filho, Citation2021), Cecilia Donnagelo (Carvalheiro et al., Citation2014; Donnagelo, Citation1976) and Juan Samaja (Samaja, Citation2005).

Social determination explains the mode of becoming of various dimensions of the reproduction of our society. In other words, it explains the social-natural mode of becoming and the formation of the specific socio-environmental characteristics and forms that comprise collective health in the context of a dynamic, multidimensional process.

This perspective on health as a complex process considers the dialectic and interdependent relationships in various dimensions. We understand that the more complex subsumes the less complex, but the latter also conserves relative autonomy.

Seen in this way, the study of the process of social determination transforms the foundations of epidemiology and opens up the spectrum of health, allowing us to understand a new and enriching horizon of health rights and look at the challenges of ethics in a different way. Substituting empirical causality by determination with subsumption to the collective, explains the profound articulation of the social and the natural, the subsumption of the individual dimension in collective modes of living, and how these frameworks sit within a general logic of the accumulation of capital. Those objective concatenations explain the generative and multidimensional power of determination, going beyond the positivist notion that ended up restricting conventional public health actions and even reflections from other fields -such as law and ethics- to the individual domain in a context of psycho-biological determinism.

3. The development of equity/inequity. Equity consists of economic complementarity and sufficiency, distributive justice, democratic empowerment, and social, political, cultural, and epistemological non-discrimination with active interculturality and democratic communication. Of course, this complementarity, within a system of great historical power imbalances, also requires confronting explicit and implicit forms of discrimination. This requires decentring received forms of knowledge (including the Cartesian, etc.) and paying special attention to indigenous forms of knowing. By contrast, social inequity is the historical process of the concentration of power in specific sectors of society and the relationships of social, economic, political, cultural, administrative, and epistemic-scientific submission that multiply the asymmetry it is derived from. The construction of inequity has remote historical roots based on the rupture of community cooperation and the appearance of surpluses that could be appropriated by one sector of society. The private appropriation of social surplus has varied from the simple mercantile hoarding of the past, colonialism and slavery, centuries of appropriation of salaried labour, and hyper-neoliberal society. The latter includes forms of extraction and appropriation of new technologies and the algorithmic governance of exploitation and domination by artificial intelligence.

From the perspective of collective and individual health and the concomitant problems of law, we are interested in understanding that social exploitation and domination appear as different tentacles of power: control over and use of the property (economic power); the capacity to control consciousness, mobilisation, and engagement for strategic purposes of the dominant sector (political power); the capacity to have a massive impact on the construction of social identity and memory (cultural/epistemological/symbolic power); the capacity to model and condition policies, laws, rules, codes, administration and its priorities (administrative power); and, finally, the capacity to impose descriptions, explanations of science, and the handling of information (scientific-technical power). These forms of power are structured and developed through integrated relationships in a class, gender, and ethno-cultural matrix.

Critical epidemiology offers two key aspects in the larger conversation around inequity and the need for epistemological, ethical, and legal clarity. The first is the need to distinguish between the concepts of inequity and inequality, recognising inequality as an expression or embodiment of inequity regarding the contrasts in the enjoyment of market goods, and in terms of access to and enjoyment of the services and goods of consumption. The second is the need to understand the methodological importance and, for practical purposes, to overcome the empirical stratifications of inequality positioned from Cartesian sociology and to analyse instead asymmetrical power relations with knowledge of how social-gender-ethnic classes are composed.

Cartesian science, whether that which applies to epidemiology or law, reduces a problem of economic, political, and cultural domination by addressing it as merely an empirical contrast of categorical indicators of inequality.

In a society based on solidarity, necessary diversity is expressed positively, particularly in terms of equality amid diversity in which racial and geno-phenotypical differences find a favourable social space. In the context of the private concentration of power, the inequity at the specific level is profound, resulting in structured inequality and discrimination of difference.

4. Subsumption-relative autonomy: The relative autonomy within subsumption is the determinant connection inherent to the processes that belong to the different complex domains of social reproduction, in which the more complex subsystem imposes its conditions on the dynamics of the less complex, generating embodiments. In the less complex individual bio-psychological domain, for example, people develop with their own psychological, physiological, and genetic rules of reproduction of the subject's biology. However, their complete functioning corresponds and is conditioned -under potentialities of replica- by the social reproduction conditions of the personal style of living, conditioned by those of their collective mode of living.

It is the dialectic movement between subsumption as an inherent connection between the subject and the movement and material organisation of social and spiritual life; and relative autonomy as the capacity for transformative generation of less complex processes compared to more complex ones (Breilh, Citation2021a).

We thus recognise the historicity of the biological or ecosystemic processes resulting from the movement of the artificialisation of the general productive and social origin.

5. Society-nature (S-N) metabolism is the historical relationship between a society with a natural foundation and the surrounding nature that is socially transformed. In other words, there is unity in the diversity of natural and social history, with humans being changed when they change nature (Schmidt, Citation1978). Realising human social reproduction in that dialectic of transforming and being transformed by the eco-social spaces where they are in, explains the profound relationship and interdependence between the social and the natural. This relationship is broader than the set of ecological factors in expressions of health, and is a historical unit of transformation within the shared matrix of a social system that prioritises private capital accumulation. Critical epidemiology has looked at this historical metabolic relationship as a key element of social determination since 1977 (Breilh, Citation1977). It questions the pseudo-comprehensiveness of the popular paradigm of eco-health, which is a Cartesian reading of the relationships with nature viewed from the perspective of environmental ecological factors.

If we look at the transcendence of society-nature metabolism from the challenge of revisiting the right to health and the ethics of our profound connection to nature, we must consider its relationship to the different domains of metabolism: in the critical processes of metabolic relationships in the general domain; in the metabolic patterns in the particular domain with productive activities and modes of living (of class, gender, and ethnicity); and in the family-personal metabolic relationships in the individual domain. This allows us to identify new justiciable elements in order to improve the law and the right to health.

Far from representing a determinist option or, even worse, apologising for economism or historical determinism, the dialectic we refer to does not recognise any linear progress of society and its health. Nor does it sustain the absolute primacy of economic material over political culture or the primacy of social over the biological-natural. In the proposal presented here, the material is intertwined with socio-political and socio-cultural expressions in a movement between subsumption and autonomy. The same happens with the individual-collective relationship or the society-nature relationship, and the development of the dialectical movement between them depends on the development of those processes and their contradictions. It is always a complex process that is neither purely nor primarily economic, political, cultural, or metabolic. All of this comprises a unit that moves amid diversity and in the midst of a complex movement.

These analytical tools are a vital source for revisiting the connection between the right to health, the rights of nature, and the transformation of productive ethics that emerges from the ecosophic richness of Andean ancestral thought and the wise experience of peoples who have developed their social reproduction in neoliberal cities and a new neoliberal rural experience.

As part of a movement to decolonise Cartesian epidemiology, ecology, and the positive law with its reductionist cannons, we have to organically articulate various forms of knowledge of life and health that emerged from various cultures through centuries of experience. Boaventura Santos has worked on this socially and epistemologically emancipatory and democratising movement, calling it an ecology of knowledge in his axiomatic argumentation in favour of an ‘epistemology of the South.’ (De Sousa Santos, Citation2014). This process of intercultural translation based on in-depth interaction allows us to overcome abstract forms of universalism; identify similar, compatible agendas; realise enriching differences; and find ‘hybrid’ forms of cultural interpretation under mutual respect (De Sousa Santos, Citation2014).

This process of complex epistemological decolonisation is constantly misunderstood and threatened by huge prejudices built through centuries of Cartesian science that is notoriously present in the life and health sciences. Catherine Walsh, another notable thinker in decolonial epistemology, clarifies: ‘We are not simply looking to disarm, undo, or reverse the colonial; in other words, to move from a colonial movement to a non-colonial one, as if it were possible for its patterns and traces to cease to exist. The intention is instead to identify and provoke a positioning of transgressing, intervening, in-developing (in-surgir in Spanish) and impacting … ’ (Walsh, Citation2009, pp. 14–15)

This proposal of a meta-critical methodology goes hand in hand with and complements the ecology of knowledge proposed by Santos (De Sousa Santos, Citation2014). It shares the urgent need for a counter-hegemonic science, the questioning of philosophical monism or universalism, and the questioning of the reification or objectification of reality. Both also respect the cognitive validity of other potent and legitimate forms of knowledge with firm humility and share the urgency of integrating intercultural thought. The meta-critical methodology seeks to travel that same path, integrating such an interpretive movement into the material foundation of the historical subjects that comprise complex knowledge and their position in the power structure in which they operate and think. In other words, it seeks to weave together narratives on the value of life, modes of protecting it and promoting it with social reproduction, and the processes of the social determination of health.

In methodological terms, the metacritique that we propose in the health sciences includes -as articulating precepts- complex thought, multidimensionality, emphasising qualitative expressions (narratives), and quantitative expressions (statistics) in a dialectic way. It thus breaks the inductive empirical moulds of old statistics and theories based on conventional anthropology (Breilh, Citation2021a).

The substance of reform in healthcare and ethics: Healthy-protector dialectic vs. the unhealthy-destructive 4 S’s of life

Thus far, I have explained the cardinal processes of the social determination of health as the basis for building and rethinking a different foundation of justiciability and rights in the hyper-neoliberal era. In other words, I have outlined new ontological and epistemological foundations that should be taken up as a point of departure and alternative logic to formulate new horizons and contents for the construction of rights to health in a participatory manner.

Now, we rethink and ground the discussion of the reform of rights to health in an intercultural critical rationality and in the context of the participatory mobilisation of social blocs or intercultural-transdisciplinary platforms (i.e. community-academy-social agents). In order to do so, we must not forget the clear distinction that Echeverría explained between reformism and reform regarding a transition of rights to health. If the option is to overcome reformism and build an effective reform in rights, we should subvert the substance of current law. Reforming the criteria and spaces of enunciation and, in line with them, formulating new ethical precepts, institutional expressions, laws, and rules such that they define, cover, guarantee, and protect life and health in a manner that carries great depth and is actionable in the current moment.

The first step is formulating the principles and requirements of a full good life. That good life can be enunciated, in our Andean context, using two perspectives that have moved on separate tracks thus far but that we have proposed dialectically integrating from the perspective of critical epidemiology (Breilh, Citation2021a, pp. 200–201). We must integrate and dialectically privilege the critical interpretative principles that underpin the analysis of a fair good life from critical academic thought in the social and life sciences, such as indigenous and popular emancipatory thought .

Table 1. Complementarity of academic and indigenous critical thought.

In his manifesto for activist intellectuals, Boaventura Santos (De Sousa Santos, Citation2014) presents a rich mosaic of versions of the good life paired with the principles of Sumak Kawsay-Ali Kawsay, Andean indigenous interculturality, and plurinationality. In this crucial inventory based on the utopias of various peoples, he includes South African Ubuntu, Indian Swadeshi and Chinese Minzhu. Others have emerged from the popular struggle connected to fair living of human rights or the good, gendered life of the feminist movement. We also see the sovereign and fair approach to eating proposed by the rural movement, through their theses on food sovereignty and agro-ecology, small-scale business movements, and popular and solidarity-based economics. These forms of knowing must be given active and special consideration, given the ways in which powerful forces have made them peripheral historically.

Another robust and diverse set of proposals for healthy living emerges from a perspective more centred on the struggles for the right to health of the Latin American Social Medicine/Collective Health movement or the Health Fora in various countries or activist networks like UNESCO’s Bioethics Network.

It is in the work that emerges from societies that mobilise and collectively fight for their rights that we must identify knowledge and work on essential reform related to health and rights. Based on that logic, from Latin American critical epidemiology, we have proposed the right to health as the substance of the reform - in terms of Bolívar Echeverría- using our proposal of the 4S’s of life and meta-critical methodology as tools ().

Table 2. Critical processes for the right to health organised in the 4 ‘S’.

Meta-critical methodology for the study of health: A new basis for law and justiciability

Meta-critical methodology: Philosophical, ethical foundations (4S’s) and their determination

We return to the question we posed at the beginning of the previous section of this article: How shall we rethink ethics, the law, and rights in terms of the elements on which the movement of life and the opportunities for living a good, fair and healthy life depend?

I propose taking up the social attributes of characterisation, affirmation, and the protection of life that have been present throughout the history of humanity as pillars of collective consciousness and coexistence. Since the dawn of human society, there has been a collective awareness of sustainability (SUS), the need to protect the continuity and enrichment of human life and nature. Alongside this, we have understood that full sustainability can only be built from freedom and autonomy, that is, in spaces of sovereignty and liberation (SOB). For sustainable and sovereign societies to guarantee life for all, solidarity (SOL) and fair management of the relationships between collective and individual rights are indispensable. Finally, the comprehensive security (SEG) of human life and ecosystems is the substrate that serves as the protective mantle and healthy final expression of the entire movement. Comprehensive (bio)security is the expression of a society-nature metabolism that is healthy and protective. It is the space in which healthy and hopeful collective modes of living are realised and, in the context of these, personally sustainable modes, sovereign and solidarity-based modes of living emerge in order to achieve full life in individuals -with their individual phenotypes, genotypes, psychic profiles, and a proactive and hopeful spirituality- in specific scenarios of individual reproduction. These are determined by the healthy forms of life of the collectives to which these individuals belong (see ).

The ethical-legal transition in health that I have proposed is not immediate. One must be aware that taking that leap is not easy, particularly as we assume the ethical value of a radicalness that responds to the hegemonic ethos. As Boaventura Santos has indicated, ‘radical ideas are not directly moved to radical practices and vice versa. Radical practices do not see themselves in available radical ideas. This mutual opacity is because the powers constituted have efficient ways of preventing the coming together of people and groups beyond that which benefits the powerful.’ (De Sousa Santos, Citation2014, pp. 5–6).

Based on those ethical-philosophical principles, metacriticism as a tool of complex thought allows us to 1) investigate the multidimensional movement of the social determination of life and health; 2) identify the critical processes and spaces related to sustainability, sovereignty, solidarity and (bio)security that generates said movement in its general, particular and individual domains; and 3) focus around that movement, bring into being the steps of the meta-critical methodology, as a dialectic, intercultural, and transdisciplinary logic.

From the perspective of the instrumentation of the method, metacriticism is a way of analysing qualitative evidence (narratives) and quantitative evidence (variables) of those critical processes that are identified in the three dimensions of determination in a dialectic, concatenated, and synchronous (quali-quanti) manner. In order to sustain said process of this dialectic and participatory knowledge, we must articulate three elements of the research process that Carlos Matus (Citation2020) described as an action triangle in critical science on health, which we have adapted to the metacritical logic and socially mobilising form of science.

Those elements that sustain, provide critical content for, and integrate a science that is simultaneously from the collective level and socially critical of collectives are: A) a programme on the incidence of critical processes of the matrix analysed to generate projects of prevention, promotion, precaution, remediation, compensation, and reparation that are collectively and participatorily designed; B) an intercultural bloc or social platform of affected-involved parties involved in this incidence programme (i.e. academy-community-public power); and C) an intercultural, transdisciplinary basis of scientific-technical research resources.

I have highlighted the ethical-epistemic argument that future research is needed on the right to health. A renewed bioethics must be formed outside of the field traced by Cartesian logic; confronting the many challenges of protection, reparation, precaution, and compensation in addition to the challenges of promotion, prevention, adequate assistance; and care of human health (Breilh, Citation2021a; Breilh, Citationin press).

The comprehensive analysis of the right to health: The ethics of in-depth justiciability

In line with the arguments presented in the sections above, we must recognise that the field of ethics and right to health reflects a broad and unfinished discussion in independent academic spaces. The goal is to clarify the philosophical foundations and ontological approaches to health as an object of law and rights; methodological procedures that guarantee comprehensive objectivity; and the instrumental, indispensable resources for generating a reform of law and rights based on new axioms.

In this section, I summarise the entry points to endow that discussion with a perspective free of the positivist conditioning of science and law.

Ethics in public health and collective health

Miguel Kottow has developed a magnificent critical overview of ethics in public health, offering various points of contact with our thesis and an unquestionable complement to the analysis I formulate here based on critical Latin American epidemiology (Kottow, Citation2012).

A departure point in the alignment is the need to revisit the notion of complexity and the ontological and epistemological dimensions from which a vision of ethics is proposed. From our perspective, one might add that both the general notion of complexity and the specific concepts of the ontology and epistemology of ethics are deeply connected to the understanding of the historical context in which legal praxis, ethics, and rights are discussed. This matter involves understanding the social determination of health as a multidimensional process in contemporary global hyper-neoliberalism.

Kottow discusses the need to extract the implications for bioethics -and, I add, for law and rights- of passing from thinking the body, to thinking medicine and to thinking public health as an ontological sphere. However, it is even more important to move on to the sphere of collective health. In Critical epidemiology and the peoplés health (2021) and previous articles, I state that collective health is a larger sphere that subsumes public health.

Above, I outline the crucial elements of a new ontology for bioethics and the right to health. The bioethics we propose is not limited to recognising ‘social interests’ from the academy. It is instead a challenge of intercultural science built ‘from below,’ thinking and acting with communities in an interpretative intercultural and transdisciplinary framework.

Kottow asks: Where are the ethics of public health? This question is valid, but insufficient. It is also not enough to ask ourselves where regulatory bioethics is, where professional ethics is, or to ask ourselves what a comparative diachronic perspective of the state of the matter contributes. However, I agree that we must set aside positivist, pragmatic bioethics and instrumental reason to move on to reflexive bioethics. Nevertheless, as I have stated here, we must discuss the place of enunciation and the cultural and theoretical-political matrix of those reflections. Otherwise, we will continue to be condemned to a rejuvenation of the same hegemonic substance of law, rights and ethics.

Given the above, we return to the key question: Where is collective health? Who must enunciate a response, and from where shall they do this?

In their classic proposal for medical bioethics, Beauchamp & Childress identify four principles: respect for autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice (Beauchamp & Childress, Citation1999). They develop a set of precepts on best practices for care. These are undoubtedly partially valid elements, but they are far from a complete and appropriate definition of the space and the content of the problems of ethics in health. They focus primarily on the individual and interpersonal interactions, without considering the collective processes of health. This focus on the individual and interpersonal, then allows processes that produce inequality to avoid consideration, critique, confrontation and change. In essence, the focus on the individual allows the engines producing inequality to continue unchallenged.

Critical, transformative bioethics must place the complex reality of the concrete reproduction of life in social spaces historically determined by the private accumulation of wealth at their ontological centre. They must interculturally and meta-critically set out alternative reasonings that emerge from the voices of impacted communities, independent scientists, experts, and public agents involved, and real projects of justice that consider the full ethics of life.

The International Society of Environmental Epidemiology’s Guide for Environmental Epidemiologists (www.iseepi.org/about/ethics.html) helps open up horizons, organising the obligations of a comprehensive practice: with the communities involved, with broader society, in the face of employers and with academic bodies. Efforts like the UNESCO Bioethics Manual for Journalists (S. Vidal, Citation2015) and Pfeiffer and Manchola-Castillo’s book (Pfeiffer & Manchola-Castillo, Citation2022) fundamentally position the right to knowledge and the human rights approach in urgent topics such as re-territorialization, protection, moral narrative, social liberation, perspectives from the South, and narratives from the victims of human rights atrocities (including racism and colonialism) and structural violence. These are collective, new, and rich projects.

Ethics and ethics committees

There is an urgent need to break the Cartesian biomedical mould used to build the precepts, modes of action, and evaluative instruments of ethics committees (Yassi et al., Citation2013). We can highlight two cardinal problems in this regard. First, and in light of the broad arguments set out in this essay, the urgency of breaking the conceptual shell of conventional bioethics and oxygenating the disciplinary field to take on two fundamental challenges: the construction of the object of ethics around the complexity of the process of social determination, using the 4S’s of life as an evaluative guide; and the transformation of the rules of ethical knowledge.

Regarding the latter, it is essential to remind the reader of a new vision for the ethical evaluation of problems in communities proposed by Kirkness and Barnhardt (Citation1991), who highlight what they call the 4 R’s of ethical research on or assessment of scientific work in communities: respect for their culture and the interculturality of parameters on that which is just and ethical; the clear and explicit recognition of the relevance that actions and projects should have for the community and their culture; the reciprocity or bidirectionality of the ethical evaluation process; and the responsibility of the production of ethics for collective empowerment.

Along that line of thought based on the responsibilities of critical epidemiology, we proposed a new model of ethical evaluation of projects and interventions in health to the Board of the Ecuadorean Academy of Medicine in 2013 (Breilh, Citation2013), outlined in the article of the Journal of Academic Ethics.

The metacritical methodology we propose and its comprehensive and intercultural logical matrix contribute to rethinking the challenges of a world affected by the collapse of justice, social ethics, the right to health, and the politics of the common good at unprecedented rates and levels. There is an urgent need to topple the technocratic spirit and instrumental reasoning, awaken consciences, and enlist our universities in efforts to address these challenges. Morals, ethics, and rights are in serious and accelerated dispute, and the future of our species and the Earth depends on which side wins the battle.

Conclusion: How to meet the challenge?

In order to be in tune with the principles and objectives for which it was created, critical bioethics must leave the biomedical mould and place as its primary object, or raison d'être, the complex ethical consequences resulting from the concrete processes of social reproduction and health conditions in collectives, with socially determined lifestyles and spaces of life. It must assume as its space of responsibility the ethics of the productive processes and economic actions of private stakeholders, of the actions of the State and government institutions, and the ethics of the forms of society-nature metabolism on which the ecosystems of life depend.

To fully meet its challenge of protecting people, it must protect communities, placing at the centre the ethics of private and public management of urban and rural spaces, serving the protection of vulnerable groups in their work, food consumption, education, recreation, community organisation and social, cultural and spiritual development.

To break out of its usual mould, integral bioethics must enunciate alternatives that emerge from the voices of the affected communities, of scientists or independent experts and public managers involved and linked to a real project of justice and the full ethics of life. That enunciation must be intercultural and meta-critical: it can only be worked on from a transdisciplinary platform, with open doors and structured within the framework of a participatory public-social programme.

It is a complex but indispensable challenge for which critical epidemiology has a fundamental role, based on the epistemological and practical strength of the paradigm of social determination and the meta-critical methodology we propose. These are powerful tools for a radical change in thought and action linked to the development of rights and ethics, a navigation chart for the forging of reform of ethics, human rights and the rights of nature.

Dedicated to the indigenous peoples and social organizations

of my homeland, Ecuador, in honour of their brave and united

struggle based on the ethics of life and social rights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The expression ‘styles of living’ applied here to individual everyday itineraries is used with the intention of differentiating it from the commonly used notion of lifestyles, which in common English suggests a collective cultural trait.

Bibliografía

- Almeida-Filho, N. (2021). Beyond social determination: Overdetermination, yes!. Cadernos de saude publica, 37(12), e00237521. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00237521

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (1999). Princípios de ética biomédica (Vol. 1). Masson Barcelona.

- Breilh, J. (1977). Crítica a la interpretación ecológico funcionalista de la epidemiología: Un ensayo de desmitificación del proceso salud-enfermedad., Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana de Xochimilco].

- Breilh, J. (1977/2010). Epidemiología. Economía Política y Salud. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar-Corporación Editora Nacional.

- Breilh, J. (2003). Epidemiología Crítica. Ciencia emancipadora e Interculturalidad. Lugar.

- Breilh, J. (2009). Hacia una construcción emancipadora del derecho a la salud. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar.

- Breilh, J. (2010). Ciencia emancipadora, pensamiento crítico e interculturalidad. UASB-DIGITAL, Repositorio institucional del Organismo Académico de la Comunidad Andina, CAN.

- Breilh, J. (2013). Evaluación ética de proyectos de investigación en salud (No clínico experimentales). Academia Ecuatoriana de Medicina.

- Breilh, J. (2021a). Critical epidemiology and the people's health. Oxford University Press.

- Breilh, J. (2021b). The social determination category as an emancipatory tool: The sins of “expertise” with regard to Minayo's epistemological bias. Cadernos de saude publica, 37(12), e00237621. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00237621

- Breilh, J. (in press). Enfoques contrarios sobre ciencia, agricultura y salud: la ciencia cartesiana frente al saber crítico comunitario-académico. In J. Breilh, J. Spiegel, & M. J. Breilh (Eds.), Pensamiento agroecológico y metodología meta-crítica. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar.

- Carvalheiro, J. d. R., Heimann, L. S., & Derbli, M. (2014). O social na epidemiologia: um legado de Cecília Donnangelo. Instituto de Saude.

- Clark, E. G., & Leavell, H. R. (1965). Preventive medicine for the doctor in his community: An epidemiological approach. McGraw-Hill.

- De Sousa Santos, B. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Routledge.

- Donnagelo, M. C. (1976). Saude e sociedade, FM/USP].

- Echeverría, B. (1975). Notas de seminario sobre el capital y la salud. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

- Ferrante, E. (2021). Inteligencia artificial y sesgos algorítmicos ¿Por qué deberían importarnos? Nueva sociedad, 294, 27–36.

- Harding, S. (1993). Eurocentric scientific illiteracy–a challenge for the world community. In S. Harding (Ed.), The ‘racial’ economy of science: Toward a democratic future (pp. 1–29). Indiana University Press.

- Kirkness, V. J., & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and higher education: The four R's—Respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education, 30(3), 1–15.

- Kottow, M. (2012). Bioética crítica en salud pública: ¿aguijón o encrucijada? Revista Chilena de Salud Pública, 16(1), 38–46.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Blackwell

- Matus, C. (2020). Adiós, señor presidente. Universidad Nacional de Lanús.

- Michaels, D. (2008). Doubt is their product: How industry's assault on science threatens your health. Oxford University Press.

- Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

- Pacheco, V. M. (2022). Bioética (ética) y pensamiento en salud. Taller de Historia de la Salud.

- Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. Routledge.

- Pfeiffer, M., & Manchola-Castillo, C. (2022). Manual de Educación en Bioética. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México- UNESCO.

- Piketty, T. (2022). El capital en el siglo XXI. Fondo de cultura, económica.

- Potter, V. R. (1970). Bioethics, the science of survival. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 14(1), 127–153. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.1970.0015

- Proctor, R. N., & Schiebinger, L. (2008). Agnotology: The making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford University Press.

- Ribeiro, S. (2016). Cuarta revolución industrial, tecnologías e impactos. América Latina en Movimiento.

- Sackett, D. L. (2000). The sins of expertness and a proposal for redemption. BMJ, 320(7244), 1283. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1283

- Samaja, J. (2005). Epistemología y metodología: Elementos para una teoría de la investigación. Eudeba.

- Schmidt, A. (1978). El concepto de la naturaleza en Marx. Siglo XXI

- Schwab, K. (2016). The fourth industrial revolution. World Economic Forum.

- Subirats, J. (2019). ¿Del poscapitalismo al postrabajo? Nueva sociedad (279).

- Tapia, L. (2013). Lo político y lo democrático en Bolivia. Autodeterminación.

- Vidal, S. (2015). Manual de bioética para periodistas. UNESCO.

- Vidal, S. M. (2022). Ética y negociaciones para el acceso a vacunas: excepcionalismos metodológicos y éticos. Revista Colombiana de Bioética, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.18270/rcb.v17i1.3935

- Walsh, C. (2009). Interculturalidad, estado, sociedad. Universidad andina simón Bolivar, Sede Ecuador.

- Wu, T. (2020). The curse of bigness: how corporate giants came to rule the world. Atlantic Books.

- Yassi, A., Breilh, J., Dharamsi, S., Lockhart, K., & Spiegel, J. M. (2013). The ethics of ethics reviews in global health research: Case studies applying a new paradigm. Journal of Academic Ethics, 11(2), 83–101. doi:10.1007/s10805-013-9182-y