ABSTRACT

Despite the widespread adoption of Theories of Change (ToC) for programme evaluation, the process of collaboratively developing these theories is rarely outlined or critical analysed, limiting broader methodological discussions on co-production. We developed a ToC as part of E le Sauā le Alofa (‘Love Shouldn’t Hurt’) – a participatory peer-research study to prevent violence against women (VAW) in Samoa. The ToC was developed in four phases: (1) semi-structured interviews with village representatives (n = 20); (2) peer-led semi-structured interviews with community members (n = 60), (3) community conversations with 10 villages (n = 217) to discuss causal mechanisms for preventing VAW, and (4) finalising the ToC pathways. Several challenges were identified, including conflicting understandings of VAW as a problem; the linearity of the ToC framework in contrast to intersecting realities of people’s lived experiences; the importance of emotional engagements, and theory development as a contradictory and incomplete process. The process also raised opportunities including a deeper exploration of local meaning-making, iterative engagement with local mechanisms of violence prevention, and clear evidence of ownership by communities in developing a uniquely Samoan intervention to prevent VAW. This study highlights a clear need for ToCs to be complemented by indigenous frameworks and methodologies in post-colonial settings such as Samoa.

Introduction

Understanding the theories that underpin complex interventions is increasingly recognised as good practice in global health (De Silva et al., Citation2014). Commonly referred to as theories of change (ToC), programme theories about why and how interventions work help to clarify and establish consensus on causality (Blamey & Mackenzie, Citation2007). In contrast to sociological theories such as Foucault’s governmentality or psychological theories of behaviour change (Coryn et al., Citation2011), ToCs are theories about the mechanisms through which an intervention is thought to bring about change in the health and social outcomes being addressed. However, despite the widespread use of ToCs in programme evaluation for social and health interventions, the process for developing these theories through consultation with stakeholders is rarely described or critically examined for how it meets project goals and objectives.

International non-government organisations and government donors – including the Children’s Fund, UN Women, the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) – have used ToCs and related outcome frameworks as part of programme evaluation for decades (Contreras et al., Citation2011; James, Citation2011; Rogers, Citation2014). However, the practical realities of large international organisations means that many ToCs are developed by programme staff or consultants who are often distant from intended programme beneficiaries, or as part of the programme’s evaluation rather than its design (Ghate, Citation2018). Similarly, ToCs are frequently designed directly from existing theoretical models of social and behavioural change as a means of ensuring programme evaluations are theory-driven and evidence-based (Abramsky et al., Citation2012; Coryn et al., Citation2011; Jennings et al., Citation2019).

While certainly valuable as part of a theory-driven approach to programme evaluation and design, developing a ToC from existing literature moves away from the community engagement origins of the practice (Mason & Barnes, Citation2007). This has certain limitations in ensuring that ToCs are tailored to the programme context, which may in turn have consequences for the success of the intervention (Blamey & Mackenzie, Citation2007; Brand et al., Citation2019). A more hybrid approach has recently been used by programme evaluators that involves collecting primary data and conducting expert and stakeholder consultations alongside reviewing published theory, to develop a more robust ToC informed by the local context in which the intervention is to be implemented (Daruwalla et al., Citation2019; Eisenbruch, Citation2018). This approach has advantages for bringing a community perspective into the research design, and ensuring that an intervention is workable.

This emphasis on community engagement in ToC development complements the move within the academic literature towards decolonial approaches to research practice (Mannell et al., Citation2021; Weiss, Citation2021). Recognising the role of many research methodologies in reproducing long-standing inequities between researchers and research participants and the dominance of Northern researchers over the production of knowledge (Bishop, Citation2011; Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999), decolonial approaches aim to subvert this by bringing marginalised voices into theory and intervention development (Connell, Citation2015). For example, indigenous and non-indigenous scholars working in settler colonial countries such as Aotearoa-New Zealand, Canada, Australia, the US and South Africa often draw on indigenous frameworks for healing and wellness (Lee, Citation2022; Ministry of Health NZ, Citation2022), or community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches informed by indigenous culture and worldviews (Durie, Citation1994; Fiedeldey-Van Dijk et al., Citation2017; Pulotu-Endemann & Tu'itahi, Citation2009; Whitesell et al., Citation2020).

In this article, we draw on a case study of ToC development as part of a participatory process for co-designing an intervention to prevent violence against women (VAW) in Samoa. In this study, researchers, non-governmental organisation (NGO) staff, peer researchers and their local communities worked collaboratively to develop a ToC, which directly reflected local priorities and needs. We describe the process taken and reflect on the advantages and challenges of developing ToCs in partnership with communities as part of a bottom-up and decolonial approach to VAW research.

E le Sauā le Alofa (‘Love Shouldn’t Hurt’)

E le Sauā le Alofa (‘Love Shouldn’t Hurt’) is a four-year participatory mixed methods project to prevent VAW in Samoa through intervention co-development. The project is part of a broader research study to understand community mechanisms of VAW reduction in the world’s highest prevalence settings called the EVE Project (Evidence for Violence prevention in the Extreme) (Mannell et al., Citation2021). With a prevalence rate estimated at 39.6% of women experiencing physical, sexual and/or emotional forms of violence in their lifetime (Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Citation2020), Samoa is above the global average of one in four women said to experience violence and among countries with the highest VAW prevalence globally (Sardinha et al., Citation2022).

Samoa is an independent country located in the Polynesian region of the Pacific Ocean, in close physical proximity to American Samoa, Fiji and Tonga. With an indigenous culture over 3,000 years old, Samoa has a unique combination of traditional culture and social structures, and modern influences. Community life in Samoa is defined by both the aiga potopoto (extended family or clan) and nu’u (village) structure with village councils that govern local bylaws. Village councils are organised according to a local system of governance known as the fa’amatai, where each family has a hierarchy of matai (high chiefs), the more senior of which usually represents aiga interests on the council. While matai titles are mainly bestowed upon men, women have held matai titles since before western European colonialism. Women matai numbers are increasing slowly as more and more women take up public leadership roles.

Religion is another dominant social structure shaping Samoan society, and a foundational principle of Samoa’s constitution. Nearly 97 percent of the population identify as Christian (Scroope, Citation2017). Christianity has long been considered one of the cultural foundations contributing to widespread acceptance of violence against women in the Pacific (Kruse, Citation2021; Nash, Citation2006; Wendt, Citation2008). Prior to the arrival of the European missionaries in the late nineteenth century, the country practiced a complex polytheistic religion worshipping human and non-human gods and goddesses. Women had assumed powerful statuses of feagaiga (covenants) or tamasa (sacred child) which ascribed them sacred power and high regard within their families (Latai, Citation2015). As a result of the nation’s conversion to Christianity, social structures were rearranged, giving rise to conservative values and the overarching theme of patriarchy. Previous contextual research considers the complicity of Christian traditions in perpetuating gender inequalities, gender violence, and rape-supportive social discourses (Schoeffel et al., Citation2018).

The E le Sauā le Alofa project is a collaboration between 10 Samoan villages, the Samoa Victim Support Group (SVSG), the National University of Samoa (NUS), the Samoa Bureau of Statistics, and University College London (UCL). SVSG – a Samoan NGO specialising in emergency response and shelter for survivors of violence – is the main link between the village representatives and the research teams at UCL and NUS. Since its inception in 2005, SVSG has developed a network of over 1,000 village representatives in villages across the country as a means of responding quickly and effectively to cases of violence. Drawing on this network, the E le Sauā le Alofa project is engaging and training 20 of these representatives and 10 village elders (mentors to the project) in collecting their own data from their local villages about VAW and strategies for its prevention, developing a TOC based on the data collected, and co-designing an intervention from the international evidence of what works to prevent VAW in community settings. E le Sauā le Alofa aims to centre indigenous perspectives on VAW and its reduction in the development of a local intervention to prevent VAW, consistent with the decolonial research approach described previously.

The ToC process and the broader effort to co-design an intervention is based heavily on an epistemological commitment to decolonising VAW research and honouring fa’asamoa (‘the Samoan way’). In practice, this means integrating Samoan cultural practices and meanings into the methods used to collect and analyse data, and putting the locus of control over the project’s results into the hands of SVSG’s village representatives, hired as community-based researchers (CBRs) for the study for their intimate understanding of Samoan cultural practices and protocols. Ethical approval for the study was received from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of both UCL (ref: 9663/002) and the National University of Samoa (ref: 20200609).

Methods

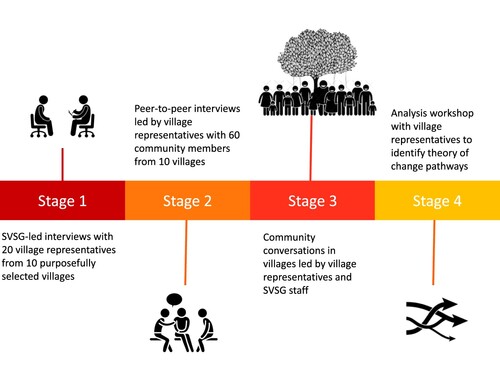

In the ten-month period from November 2020 until September 2021, SVSG led a ToC development process with the 10 Samoan villages as part of co-designing an intervention to prevent VAW. This involved four phases: (1) semi-structured interviews with village representatives as part of an induction workshop; (2) peer-led semi-structured interviews with community-based key informants, (3) community conversations to discuss causal pathways for VAW and its prevention; and (4) a final workshop activity with village representatives to finalise the ToC pathways.

Recruitment and selection

Twenty village representatives were purposefully selected from SVSG’s existing network of village representatives. This selection was based on ensuring diversity across a range of criteria including rural/ urban areas, size of village, and number of cases of VAW reported to SVSG over the past 15 years. One man and one woman were selected from each of 10 villages to ensure a gender balance.

Village representatives were recruited through an initial interview with SVSG staff to assess each individual’s personal commitment and capacity to participate in the project. Once selected, village representatives were invited to join an introductory workshop where they were introduced to the project and given 3-days of comprehensive training on conducting interviews about VAW in November 2020. After the training, village representatives were given the choice to continue with the project and if they agreed, asked to sign a consent form.

In the next stage, village representatives recruited three members each from their villages to participate in semi-structured interviews. During the training village representatives discussed and agreed on an appropriate selection strategy, which included people in leadership positions as well as those without leaderships titles, religious representatives, members of the village women’s committee, and men and women who had received SVSG’s services either as survivors or perpetrators of violence. These community-based key informants were approached by their local village representatives and asked to sign a consent form before participating in the interview.

Following the interviews, village representatives recruited additional village members to participate in a TOC meeting facilitated by themselves with support from SVSG. Anyone over the age of 18 who lived in the village was eligible to participate in the meeting, and all participants were asked to sign a consent form. A total of 217 village members participated in these meetings across the islands of Upolu and Savai’i, as shown in .

Table 1. Community Meeting Attendance.

Data collection

Interviews with village representatives: In-depth semi-structured interviews about violence within the village and local community strategies for its prevention were initially conducted by SVSG staff with the 20 village representatives (Stage 1). The first few interviews were transcribed and translated into English in preparation for a conversation with the UCL research team and small modifications to the topic guide were made before proceeding with the remaining interviews.

Peer-to-peer interviews: Village representatives then used the same topic guide to conduct interviews with three key informants from their respective villages (n = 60) (Stage 2). The topic guide included questions about individual’s understanding of violence, what types of violence occur in their village, what they believe the main causes of the violence are, and what strategies are in place locally to address VAW. They were also asked to share a local ‘artefact’ from their village that would help us understand VAW. These artefacts included songs, oral histories, proverbs, games and traditional practices that were associated with the specific social and cultural history of the villages. All interviews were audio recorded using mobile phones, and later transcribed and translated into English by SVSG staff.

Community conversations: Drawing on the concept of talanoa as an open and inclusive dialogue in Pacific cultures (Suaalii-Sauni & Fulu-Aiolupotea, Citation2014), community conversations were held with village members. These conversations were facilitated by SVSG and the village representatives as a problem tree activity (Stage 3). Village members were first divided into groups of men and women, and each group was asked to identify the underlying causes of violence (roots), how it manifests (trunk), and its consequences for women (branches). They were given a piece of flipchart paper to map these out visually as part of a tree structure. They were then asked to draw a solutions tree in a similar way, with potential solutions targeted at the three different levels (roots, trunk and branches). Once this was complete, as a full group, village members were asked to identify similarities between the tree created by men and the tree created by women. Detailed notes from these community conversations were taken by a SVSG staff member for later analysis .

Co-developing a theory of change from the data

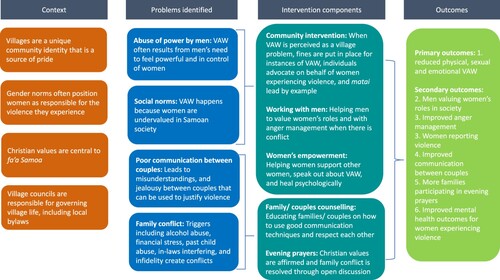

A visual map of the theory of change (see ) was discussed, adapted and refined through conversations between the UCL research team, NUS and SVSG over the course of data collection. Following the interviews (Stages 1&2), the UCL research team conducted a preliminary thematic analysis driven by the research question: what are the mechanisms of violence prevention identified by village members in Samoa? Transcripts were read multiple times by JM, HL and CV and an initial list of inductive codes were identified under two broad categories: (1) factors that perpetuate VAW and (2) mechanisms for preventing VAW. Potential causal pathways between ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’ were then extracted from the data and themes were rearranged into a ToC visual map () highlighting potential intervention components which could address problems identified for this context (De Silva et al., Citation2014). This process of identifying pathways between themes drew heavily on thematic network analysis as described by Attride-Stirling (Citation2001) and the idea of considering not only themes but how they are connected to one another.

The map of potential pathways developed by the UCL research team was shared with NUS and SVSG for modification in the first instance, before being shared with the village representatives at a workshop (Stage 4). In one particular workshop activity, facilitators (NUS and SVSG) gave the village representatives a list of problems, solutions and ideal world examples that had been identified from the peer interview data, as well as the map of potential pathways. Village representatives were asked to work in groups to create connections between these problems, solutions and ideal outcomes, using the map of potential pathways as a visual aid to encourage theoretical thinking about pathways of change.

The map presented in represents the theory of change as it was at the end of this process, including inputs from SVSG and NUS, analysis of the peer-to-peer interviews, notes from the community conversations, and the participatory activity with village representatives to create connections between problems, solutions and ideal outcomes.

Analysing the process

In this paper, we present our reflections on the process of co-creating a theory of change with our diverse research team and the village representatives involved in the project. Throughout the process, we documented the reasons behind analytical decisions following the advice of Nowell et al. (Citation2017). In developing the structure of this paper, UCL (JM, HL, LB, CV), SVSG (PT, SH, SF, SLC), and the National University of Samoa (HT) collaboratively reflected on field reports, recorded conversations and personal notes taken by team members. Over the course of several meetings, we developed a preliminary set of thematic reflections on this process of creating a TOC. The themes were then refined and consolidated during a collaborative writing and reviewing process in which several of us wrote sections of this paper, and circulated revisions for comment.

Reflections on the process

The process of developing a ToC in collaboration with village representatives and their communities was complex, with several challenges arising from interactions between the social context of Samoa and global health as a field of research. We discuss four key challenges: (1) conflicting understandings of the problem, (2) linearity of the ToC framework, (3) emotional engagements in VAW prevention, and (4) theory development as a contradictory and iterative process.

Conflicting understandings of the problem

As academics and practitioners working on violence from within research institutions and NGOs, we approach the problem of VAW from a feminist perspective whereby violence results from structural and societal gender inequalities that position women as inferior to men (Dobash & Dobash, Citation1979). Gender inequalities and norms are understood as justifying acts of violence when women do not behave in ways that conform to preconceived notions of womanhood and femininities (Heard et al., Citation2018), for example, when they do not dress in particular ways (Ringrose & Renold, Citation2012), or fail to adhere to prescribed caregiving roles (Namy et al., Citation2017). We often use this feminist conceptual framework to inform our reading of discourses, behaviours and social norms surrounding violence.

The causes of VAW in Samoan society shared by the village representatives and in interviews with community members often contradicted the feminist ideals outlined above. Women were sometimes blamed for the violence they experience by both male and female village representatives, and in these cases, solutions to addressing VAW were framed as correcting women’s behaviour. Societal gender inequalities that position women as deserving of violence have shaped and framed not only how men, but also how women, view women’s experiences of violence. For example:

[Original] Ou ke kalikogu, e leai se mea e kupu fua, e le kei kei fasi.

E ala a oga kupu le sauaiga o le kigā, o le malosi o le gutu oso, o le komumu.

Pei e magao foi le kigā ia e sisi ifo foi loga ia ikulagi i luga, e fa’akaukūkū a ma le kamā. Pei o le ala lega o le sauaiga o i kakou e kamā, oga o le mea lega, e le mafai foi oga kakou koilalo i kakou. Ua kakou magagao foi e kukusa kakou ma kamā, ma kakou pulea kamā ma le fagau, ae e le kaliaiaga e kamā ga ikuaiga uiga. O le mea lega e kau loa i le mea e gaka ai, fasi loa e le kamā, e a’oa’o ai loga koalua, ma fai ai ma lesoga ia oga iloa loga kulaga i kokogu o le aiga.

[English translation] I do believe abuse and violence happens for a reason. Sometimes women experience violence because they cannot control themselves, they run their mouth to the point that their husbands can’t take it anymore and end up beating them. I believe that this happens in the families when women think that they are equal with men and they want to control the men and the children, but this is unacceptable to the husband so if the husband reaches his limit then he will use violence to discipline his wife and teach her of her place and where she stands in their family. (Community interview, woman, Savai’i)

The SVSG team chose not to challenge these views overtly, but rather to subvert potential victim-blaming by approaching community conversations/ talanoa about the causes of violence in separate groups of men and women. The separation of groups by gender allowed for more open dialogue and the generation of ideas from different perspectives than might have otherwise occurred. The two groups were then invited to come together to share their perspectives with the community. This was intended to provide a safe space for women’s voices about their experiences of violence to be heard without any pressure on individual women to divulge personal experiences to the group.

In each community, 2–3 women chose to share their personal stories of violence. SVSG staff were present to support and monitor women for any signs of distress and the potential need for follow up or future intervention. Women who shared their experiences of violence were usually older nofotane (women who reside in their husband’s village) and/or wives of high chiefs. The stories were well received by the community (and many were already known), however this created a space for an acknowledgement from the high chiefs and others of their role as perpetrators in a public forum. In part, as a result of this communitarian approach, the solutions to addressing violence that emerged from the community conversations often focused on shared responsibility for addressing violence, such as: improving communication between couples, trusting one another, developing family relationships by spending more time together, attending church together, and setting shared priorities for the family unit.

In developing the ToC, themes about the ‘abuse of power by men’ and ‘social norms that undervalue women’, identified from the thematic analysis of the peer interviews, provided an opportunity to bring feminist approaches into the conversation. These were strong themes arising from the peer interviews, and not imposed by the research team, which provided an opportunity for integrating debates on gender equality into the wider discussion about the causes of violence. It also provides evidence for how the social norms of gender inequality mentioned previously are not consistently held norms by all community members: they are contested and debated.

Linearity of toC frameworks

As part of the process of developing a ToC, participants were asked to think conceptually about the underlying causes of violence as a means of identifying the mechanisms that could be addressed as part of a potential intervention. Workshop facilitators (SVSG and NUS staff) used the problem tree activity for this purpose and explained how experiences such as family conflict may be driven by underlying root causes, such as poverty. However, this linear way of thinking was challenging for participants who saw complex interactions between the causes of violence and its effects. For example, education was perceived as both a root cause of violence (poor education leads to violent behaviours) and an effect (violence in the household prevents children from being sent to school).

This complexity in turn brought challenges for the ToC workshop activities. It was difficult to develop solutions for underlying causes of violence such as poor education. On the other hand, if education was perceived as an outcome of violence, potential solutions were often overly simplistic (e.g. send children to school), and it was difficult to consider how this would prevent violence. As a result, not all the solutions raised by participants addressed feasible or known drivers of violence in linear ways (i.e. solutions including women not playing bingo or attending church more often lacked clear pathways to VAW prevention).

A separate activity held during one of the workshops raised a related challenge. We asked village representatives to arrange a list of ethical principles for the project in their order of importance. While the facilitators had asked them to order principles from most important to least important, village representatives wanted to order the principles in a different way. The discussion focused on how a principle about ‘Christian values’ (i.e. approaches to the prevention of VAW should be developed in partnership with the Church) belonged in the middle as the ‘heart’ of Samoan culture, whereas ‘love’ (i.e. VAW prevention approaches should promote peace and harmony within families) belonged at the bottom because it was the foundation of everything. This provided the project team with another example of how linear frameworks were challenged as part of workshop discussions with village representatives.

Emotional engagements in VAW prevention

All work on VAW is emotionally challenging for both the participants and research/ practitioner teams. The expression of emotions (e.g. crying) was a common occurrence during the development of the ToC. Village representatives often shared stories and cried together during training workshops. Community conversations were emotional with village chiefs who had perpetuated violence crying at the realisation of the impacts it has had, and meetings between UCL and SVSG also involved many tearful moments. There were also other emotions that arose, including the use of humour during the training workshops, which provided a means of reconciling the seriousness of the issue with a growing awareness that violence needed to be talked about more openly.

Rather than a challenge for the project, this emotional expression provided a number of advantages. SVSG, NUS and UCL have developed a strong relationship over a vast distance, at a time when travelling has been impossible due to COVID-19 restrictions. The expression of emotions within community conversations added a deeper level of empathy for survivors who chose to tell their stories, and motivated community members to want to address the problem. Village representatives often shared personal stories of violence during training workshops. The expression of strong emotions was often a critical turning point in these workshops, where emotions provided a means of expressing the importance of the topic and the need for change. As said during a meeting by a SVSG staff member: ‘We believe that being in tune with the emotional aspect of working with such a difficult topic is what makes us human.’

Theory development as a contradictory and iterative process

The ToC process of conducting workshops with village representatives and holding community conversations, while important as a process, did not produce a final consensus about what would change violence in communities. Perceptions of how to prevent VAW are widely contested, as shown in the following contradictory quotes from village members:

[Original] O alii ma faipule latou te faamalosia fa’asalaga i alii latou te sauaina tina ma tamaitai. E le taitai ona moea se mataupu fa’apea i totonu o si o matou nuu. O le mea foi lea ou te talitonu ai, e mafai ona taofia le sauaga peā tatou tutu fa’atasi mo se suiga. E tatau ona amata ma i o tatou afioaga.

[English translation] The village council enforces punishment to men who abuse women and girls. By saying this, I believe it could be stopped if we work together to enforce it. But it needs to start from the communities we live in. (Community interview, woman, Savai’i)

[Original] Iā a’u lava ia, o lo’u popolega, a ou alu gei e ka’u i alii ma faipule ua sauaiga e le koalua o la’u kama, ia la’u kama, ia o lesi foi la ga mafakiaga kele aua o le a vevesi le makou aiga, ma fai le figauga po’o ai o le a faia le sala o le a ku’uiga mai e alii ma faipule.

[English translation] But for me, my concern is, if I report my son in law to the village council for abusing my daughter, it will add more to the problem because then my family will argue over who will finance the penalty handed down by the village council. (Community interview, woman, Upolu)

Our experience of collaboratively developing a ToC was that the iterative nature of the process was essential in creating spaces for discussion and debate about these contradictions. We went through multiple stages of data collection, which provided a unique opportunity to capture insights that would have been lost had we stopped at the first stage, or if we had not allowed sufficient time (i.e. several months) to reflect on the results before collecting more data.

For example, one insight that would not have arisen from a one-off consultation with local communities was the importance of evening prayers. The initial ToC developed from interviews with village representatives and synthesised by the UCL research team did not include this practice (where extended families come together to pray as a group at the end of every day) as a mechanism for violence prevention because it did not have a clear pathway to reduced violence. It was only through collaborative analysis and refinement of the ToC with the village representatives and SVSG staff that its importance as a mechanism was recognised – evening prayers provide a time for families to discuss problems they may be facing, including violence, within a Christian faasamoa framework of forgiveness and peace.

The project timeline agreed with the funder required us to move onto developing and testing a pilot intervention based on the ToC at the end of two years of fieldwork. However, we are intimately aware that the ToC process should continue, and that hypothesised pathways of violence prevention need to be further refined and shaped as the pilot is implemented.

Discussion

Despite its challenges, developing a TOC in partnership with community members did fulfil our objectives of engaging Samoan communities in dialogue about how to prevent VAW and giving them ownership over a potential intervention. The significance of this for strengths-based approaches to intervention development and the sustainability of interventions should not be overlooked. In this article, we have focused on the challenges inherent in the process as a means of provoking new questions about both epistemological and pragmatic assumptions made by ToCs as tools for intervention evaluation.

Our experience highlights the strengths of ToCs in clarifying assumptions about how interventions work, and when developed as part of a collaborative process, shows how they can be used to open up discussions about conflicting epistemologies. As facilitators of a community-based process, we felt obliged not to share our understandings of gender inequalities too early in the process, and not until community members had had a chance to fully express their own views – a process that took months of engagement, data collection and ‘listening’ through interviews, workshops and talanoa. This was an uncomfortable position to be in, particularly when community members blamed women for ‘frequently attending bingo’, or otherwise acting in ways that were seen as ‘provoking’ violence.

Chadwick (Citation2021) talks about discomfort in research as providing the potential for a ‘transformative praxis’ of resistance and anti-colonial feminist research. Rather than something that should be avoided in search for a particular ‘truth,’ discomfort is seen as an interpretive resource. This resonates with our experience of developing a ToC for VAW prevention in Samoa, particularly when solutions proposed by communities seemed to reinforce what, from our feminist perspective, is the root cause of VAW: gender inequalities. A recent national Family Safety Report revealed that over 60% of women believe that they deserve to be beaten and abused (Samoa Office of the Ombudsman, Citation2018), and local feminist ideals are often subverted by Samoan women’s greater interest in demonstrating Christian piety and morality (Schoeffel et al., Citation2018). Many NGOs see this neglect of feminist ideals as a stagnating factor in ending violence against women in Samoa (2022, personal correspondence).

In developing a TOC, it was through not being too quick to offer our own feminist opinions and in supporting community ownership over the process that we were able to bear witness to the ways in which unequal gender norms are often openly contested within communities. This is shown in the example of the different understandings of the impact of the penalties imposed by some village councils held by village members. In listening to community members, we were able to provide a space for recognising new modalities of women’s agency (Mahmood, Citation2012) – ways in which Samoans are resisting unequal gendered discourses subversively, often by drawing on other more powerful discourses within the public sphere. For example, adherence to religious practices such as evening prayers may provide new opportunities for women to gain power and authority without directly challenging gender norms in ways that lead to conflict or increases in violence. Research in both predominantly Christian and predominantly Muslim contexts has shown how religious adherence is a powerful discourse that can carry weight and authority even for individuals who lack power in other areas of their lives (Simonič, Citation2021). Our discomfort during the ToC process was important, and helped us interrogate the idea that feminist research is only feminist if it is constantly challenging gender inequalities as part of an emancipatory project of freeing women from patriarchal social structures (Narayan, Citation1989).

Although recognising different modalities of women’s agency provides a means of acknowledging the inherent power of certain voices and discourses within a context, there are also steps we could have taken early on to strengthen the capacity of the village representatives to facilitate and lead these debates. Many of the village representatives’ own understandings of the causes of violence are grounded in the same victim-blaming language as their peers (Siu-Maliko, Citation2016), and this does pose problems when we, as a research team, ask them to conduct research on violence in safe and ethical ways (e.g. not using this language when speaking to women experiencing violence as a key example). In our case, the village representatives had substantial training from SVSG on women’s rights, responding to situations of violence, and women’s safety. However, those who had gone through their own process of critical engagement with the role that gender norms and the acceptance of violence play in perpetrating violence against women were more able to engage fully in the ToC activity.

For the community members, the opportunity for critical engagement was provided through the community conversations/ talanoa. These conversations provided an essential space for bringing different understandings of violence and its prevention into conversation with one another at the community level, and the success of this approach appears to be in women telling their own personal stories of violence. Hearing such stories generates feelings of empathy and compassion that are similar to the experience of discomfort described previously – both generate an emotional response that shifts the conversation and challenges us to think in new ways. Feminist researchers refer to the change or shift in perceptions through emotional engagements as affect (Hemmings & Kabesh, Citation2013), however, the compassion with which Samoan communities listen to women’s stories is perhaps better understood using the Samoan concept of fa’aaloalo, where respect is afforded to others with the intention of honouring social relationships through processes of participation and reciprocation (Peteru, Citation2012).

In our commitment to decolonial research, it is also necessary to critically consider the ToC as a methodological practice that is aligned with Western ways of thinking (Zanotti et al., Citation2020). The example of how village representatives resisted the linear approach taken to the ToC sheds light on the assumptions ToCs make about programmes needing to address a set of pre-defined outcomes. These linear assumptions are often critiqued as stemming from a post-positivist research paradigm, which assumes that the reality of how change happens is detectable, at least probabilistically, and that objectivity is an ideal that all research should strive for (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1982). This contrasts with indigenous epistemologies, or ways of knowing, many of which focus on interconnections and interdependence between people, and between people and their environment (Held, Citation2019; Kovach, Citation2015; Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003).

In Samoan culture, this interconnection is embodied within the concept of vā, which refers to the relations between people, their environment, and objects, and conceptualises this relational space as interdependent and holistic (Peteru, Citation2012). Turning individual accounts of experiences of violence and its prevention into a ToC (or any form of analytical abstraction of this kind) can be critiqued for stripping these stories of their cultural significance, and disconnecting them from the vā or vā principles (Lilomaiava-Doktor, Citation2020). However, we argue that there is still value in using Western research tools, such as ToCs (as they are currently conceptualised), in partnership with indigenous methodologies as long as there is a clear recognition of their equal importance and complementary strengths. This is aligned with a growing body of literature on conducting research that is at the interface of indigenous and Western knowledge systems (Held, Citation2019), and the need to establish two-way conversations between epistemologies while ensuring a focus on local culture and meaning-making in research practice (Suaalii-Sauni & Fulu-Aiolupotea, Citation2014).

We believe the advantages of using a ToC as a tool for eliciting conversations as part of a community-led intervention development process outweigh many of the challenges we experienced. It provides an essential tool for facilitating the next stage of the study, which involves the co-creation of an intervention to prevent VAW in collaboration with local communities (Mannell et al., Citation2021). The draft ToC will be used as a framework for ensuring that the pathways discussed during this formative stage of the study will be used to inform decisions made by village representatives about the aims of the interventions they develop for their communities. More broadly, the ToC provided a new space for discussions about what a Samoan approach to VAW prevention could look like by both village representatives and community members. Communities took clear ownership over this process with one community presenting their strategy for VAW prevention during an evening news broadcast, and another in the national newspaper (Fruean, Citation2021). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it challenged our own Western assumptions of the need for consensus on which linear pathways exist between the intervention and VAW reduction as the intended outcome.

Conclusions

Collaboratively developing a ToC with communities can be a fruitful undertaking, however, it needs to be done carefully and with full recognition of the potential limitations. We outline three key recommendations for those interested in co-producing ToCs as part of intervention development, with a particular focus on local and indigenous communities.

First, there needs to be an authentic space for indigenous worldviews to be used alongside the ToC development process. This may involve incorporating indigenous methodologies, such as talanoa and faafaletui (Pacific methods for holding open community conversations that weave together different perspectives and information) (Kruse, Citation2021; Suaalii-Sauni & Fulu-Aiolupotea, Citation2014). Another option would be to use indigenous understandings of how change happens (i.e. indigenous or decolonised logics (Sinclair, Citation2020)) to inform the theory of change as a programme theory (Reinholz & Andrews, Citation2020). In the Samoan context, this could involve using the concept of vā to inform an understanding of how change comes about through intimate connections between people, their environment, and objects, which could then be used to ensure that the ToC components include these relationships in addition or as an alternative to more conventional components such as individual motivations and behaviours.

Our second recommendation is to pay close attention to locally-defined outcomes and objectives. The inclusion of indigenous methodologies is important in part because of how they serve local objectives, such as building cultural histories and reinvigorating social relationships. As a concrete example from Samoa, a central thread of both cultural histories and social relationships is the church, which plays a key role in how violence is conceptualised in this context (Ah Siu-Maliko, Citation2019; Ah Siu-Maliko et al., Citation2019). As programme theories, ToCs often have outcomes that have been pre-defined by funders, and we would encourage a critical openness to alternative options during the ToC development process that are more inclusive of how meanings of violence are appropriated and reproduced in particular contexts (Filemoni-Tofaeono & Johnson, Citation2016).

Thirdly, we recommend being attentive to the iterative nature of the process and accepting of the fact that it may never be truly complete. It can take time to effectively co-develop a theory of change, and multiple activities can be helpful in unpacking the overlapping risk factors that drive violence in different contexts (Mannell et al., Citation2022). ToCs are embedded within complex social systems that change over time, with the influx of new people and ideas, and the influence of broader social changes or shocks (Rihani, Citation2002). We suggest a flexible and pragmatic approach to seeing ToCs as living co-constructed documents that are collaboratively produced and constantly updated.

More broadly, asking the potential recipients of an intervention what kind of intervention they would like to see and how they think it will work to achieve their own objectives is a necessary undertaking in and of itself. The development of a ToC provides a framework for asking these questions, but it may need to be used alongside other, alternative approaches, which have a stronger foothold in indigenous frameworks. For instance, we collected oral artefacts as part of the peer interviews in this project, to provide a space for engagement with Samoans’ accounts of their own cultural history and way of life. Going forward, there is important work to be done (which has been started by others (Gegeo & Watson-Gegeo, Citation2001)) on how to translate artefacts such as these into research outputs without losing their value and intended meaning. This is essential in ensuring a critical approach to the methods we use to design interventions with indigenous communities. The key insight we think our study adds to this conversation is that the methodologies we use to ask communities about what they would like to see from interventions may be just as, if not more, important than the question itself.

A statement on our positionality

This paper was written as part of a collaborative process between academics (JM, HL, LB, CV, HT, ECM, TSS) and practitioners (PT, SH, SF, SLC, ECM), all with very different positions of identity and power. As academics, many of us have PhDs (JM, LB, ECM, TSS) while others are enrolled in PhD programmes and/or in academic institutions (HL, CV, HT), which affords us with a certain amount of privilege and status in comparison with our peers. Many of us belong to and identify with Samoan ethnic, cultural and religious communities (HT, ECM, TSS, PT, SH, SF, SLC), and have contributed to the cultural, historical and linguistic reading of the theory of change described in this paper. We would like to acknowledge the leaders (both matai and religious) involved in supporting and collaborating with us on this study. Our research has been designed according to the Pacific Health Research Guidelines (2014) and principles of meaningful engagement, reciprocity, cultural sensitivity and respect.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramsky, T., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Francisco, L., Nakuti, J., Musuya, T., Kyegombe, N., Starmann, E., Kaye, D., Michau, L., & Watts, C. (2012). A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! Study): Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials, 13(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-96

- Ah Siu-Maliko, M. (2019). Tatala le Ta’ui a le Atua| Rolling Out the Fine Mat of Scripture.

- Ah Siu-Maliko, M., Beres, M., Blyth, C., Boodoosingh, R., Patterson, T., & Tombs, D. (2019). Church responses to gender-based violence against women in Samoa.

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Bishop, R. (2011). Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research. In Freeing ourselves (pp. 1–30). SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-415-7_1.

- Blamey, A., & Mackenzie, M. (2007). Theories of change and realistic evaluation: Peas in a Pod or apples and oranges? Evaluation, 13(4), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389007082129

- Brand, S. L., Quinn, C., Pearson, M., Lennox, C., Owens, C., Kirkpatrick, T., Callaghan, L., Stirzaker, A., Michie, S., Maguire, M., Shaw, J., & Byng, R. (2019). Building programme theory to develop more adaptable and scalable complex interventions: Realist formative process evaluation prior to full trial. Evaluation, 25(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389018802134

- Chadwick, R. (2021). On the politics of discomfort. Feminist Theory, 22(4), 556–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700120987379

- Connell, R. (2015). Meeting at the edge of fear: Theory on a world scale. Feminist Theory, 16(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700114562531

- Contreras, M., Ellsberg, M., Barker, G., & Women, U. N. (2011). Safe cities free of violence against women and girls global programme impact evaluation strategy. In Endvawnow.org.

- Coryn, C. L. S., Noakes, L. A., Westine, C. D., & Schröter, D. C. (2011). A systematic review of theory-driven evaluation practice from 1990 to 2009. American Journal of Evaluation, 32(2), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010389321

- Daruwalla, N., Machchhar, U., Pantvaidya, S., D’Souza, V., Gram, L., Copas, A., & Osrin, D. (2019). Community interventions to prevent violence against women and girls in informal settlements in mumbai: The SNEHA-TARA pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials, 20(1), 743. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3817-2

- De Silva, M. J., Breuer, E., Lee, L., Asher, L., Chowdhary, N., Lund, C., & Patel, V. (2014). Theory of change: A theory-driven approach to enhance the medical research council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials, 15(1), 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-267

- Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. (1979). Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. Free Press.

- Durie, M. (1994). Te whare tapa whā. Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand.

- Eisenbruch, M. (2018). Violence against women in Cambodia: Towards a culturally responsive theory of change. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 42(2), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-017-9564-5

- Fiedeldey-Van Dijk, C., Rowan, M., Dell, C., Mushquash, C., Hopkins, C., Fornssler, B., Hall, L., Mykota, D., Farag, M., & Shea, B. (2017). Honoring indigenous culture-as-intervention: Development and validity of the native wellness AssessmentTM. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 16(2), 181–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2015.1119774

- Filemoni-Tofaeono, J., & Johnson, L. (2016). Reweaving the relational mat: A christian response to violence against women from oceania. Routledge.

- Fruean, A. (2021, September 11). Village’s anti-violence strategy praised. Samoan Observer.

- Gegeo, D. W., & Watson-Gegeo, K. A. (2001). “How we know”: Kwara’ae rural villagers doing indigenous epistemology. The Contemporary Pacific, 13(1), 55–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2001.0004

- Ghate, D. (2018). Developing theories of change for social programmes: Co-producing evidence-supported quality improvement. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0139-z

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1982). Epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry. ECTJ, 30(4), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02765185

- Heard, E., Fitzgerald, L., Whittaker, M., Va’ai, S., & Mutch, A. (2018). Exploring intimate partner violence in Polynesia: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838018795504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018795504

- Held, M. B. E. (2019). Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: An unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406918821574. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918821574

- Hemmings, C., & Kabesh, A. T. (2013). The feminist subject of agency: Recognition and affect in encounters with “the other”. In S. Madhok, A. Phillips, & K. Wilson (Eds.), Gender, agency and coercion (pp. 29–46). Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, C. (2011). Theory of Change Review. In Ngo-federatie.be.

- Jennings, H. M., Morrison, J., Akter, K., Kuddus, A., Ahmed, N., Shaha, S. K., Nahar, T., Haghparast-Bidgoli, H., Khan, A. A., Azad, K., & Fottrell, E. (2019). Developing a theory-driven contextually relevant mHealth intervention. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1550736. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1550736

- Kovach, M. (2015). Emerging from the margins: Indigenous methodologies. In L. Brown & S. Strega (Eds.), Research as resistance, 2e: Revisiting critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches (pp. 43–64). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Kruse, L.-N. M. (2021). Teaching women’s histories in oceania: Weaving indigenous ways of knowing and being within the relational mat of academic discourse. Pacific Asia Inquiry, 12, 325–338.

- Latai, L. (2015). Changing covenants in Samoa? From brothers and sisters to husbands and wives? Oceania; A Journal Devoted To the Study of the Native Peoples of Australia, New Guinea, and the Islands of the Pacific, 85(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/ocea.5076

- Lee, S. (2022). Aboriginal traditional healing. Canadian Cancer Society. https://cancer.ca/en/treatments/complementary-therapies/aboriginal-traditional-healing.

- Lilomaiava-Doktor, S. (2020). Oral traditions, cultural significance of storytelling, and samoan understandings of place or fanua. Native American and Indigenous Studies, 7(1), 121–151. https://doi.org/10.5749/natiindistudj.7.1.0121

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. In Zed Books. https://doi.org/10.1353/cla.2013.0001.

- Mahmood, S. (2012). Politics of piety: The islamic revival and the feminist subject. Princeton University Press.

- Mannell, J., Amaama, S. A., Boodoosingh, R., Brown, L., Calderon, M., Cowley-Malcolm, E., Lowe, H., Motta, A., Shannon, G., Tanielu, H., & Vergara, C. C. (2021). Decolonising violence against women research: A study design for co-developing violence prevention interventions with communities in low and middle income countries (LMICs). BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11172-2

- Mannell, J., Lowe, H., Brown, L., Mukerji, R., Devakumar, D., Gram, L., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Minckas, N., Osrin, D., Prost, A., Shannon, G., & Vyas, S. (2022). Risk factors for violence against women in high-prevalence settings: A mixed-methods systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 7(3), e007704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007704

- Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

- Mason, P., & Barnes, M. (2007). Constructing theories of change. Evaluation, 13(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389007075221

- Ministry of Health NZ. (2022). Rongoā Māori: Traditional Māori healing. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/rongoa-maori-traditional-maori-healing.

- Mohanty, C. T. (1984). Under western eyes. In T. L. A. Russo (Ed.), Third world women and the politics of feminism (pp. 51–80). Indiana University Press.

- Namy, S., Carlson, C., O’Hara, K., Nakuti, J., Bukuluki, P., Lwanyaaga, J., Namakula, S., Nanyunja, B., Wainberg, M. L., Naker, D., & Michau, L. (2017). Towards a feminist understanding of intersecting violence against women and children in the family. Social Science & Medicine, 184, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.042

- Narayan, U. (1989). The project of feminist epistemology—Perspectives from a nonwestern feminist. (pp. 256–272). Rutgers University Press. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct = true&db = ioh&AN = 887387&site = ehost-live.

- Nash, S. T. (2006). The changing of the gods: Abused christian wives and their hermeneutic revision of gender, power, and spousal conduct. Qualitative Sociology, 29(2), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-006-9018-9

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Peteru, M. C. (2012). Falevitu: A literature review on culture and family violence in seven pacific communities in New Zealand. Ministry of Social Development.

- Pulotu-Endemann, F. K., & Tu'itahi, S. (2009). Fonofale: Model of health. Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann.

- Reinholz, D. L., & Andrews, T. C. (2020). Change theory and theory of change: What’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-0202-3

- Rihani, S. (2002). Complex systems theory and development practice: Understanding non-linear realities. Zed Books.

- Ringrose, J., & Renold, E. (2012). Slut-shaming, girl power and ‘sexualisation’: Thinking through the politics of the international SlutWalks with teen girls. Gender and Education, 24(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2011.645023

- Rogers, P. (2014). Theory of Change.

- Samoa Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Samoa Demographic and Health Survey-Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (DHS-MICS) 2019-20 (p. 23). UNFPA. https://pacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/fact-sheet-samoa-dhs-mics-2019-20.

- Samoa Office of the Ombudsman. (2018). National inquiry report into family violence (p. 342). National Human Rights Institution.

- Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S. R., & García-Moreno, C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399(10327), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7

- Schoeffel, P., Boodoosingh, R., & Percival, G. S. (2018). It’s all about eve: Women’s attitudes to gender-based violence in Samoa. In C. Blyth, E. Colgan, & K. B. Edwards (Eds.), Rape culture, gender violence, and religion: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 9–31). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72224-5_2.

- Scroope, C. (2017). Samoan culture. The Cultural Atlas. http://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/samoan-culture/samoan-culture.

- Simonič, B. (2021). The power of women’s faith in coping with intimate partner violence: Systematic literature review. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(6), 4278–4295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01222-9

- Sinclair, R. (2020). Exploding individuals: Engaging indigenous logic and decolonizing science. Hypatia, 35(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2019.18

- Siu-Maliko, M. A. (2016). A public theology response to domestic violence in Samoa. International Journal of Public Theology, 10(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1163/15697320-12341428

- Suaalii-Sauni, T., & Fulu-Aiolupotea, S. M. (2014). Decolonising pacific research, building pacific research communities and developing pacific research tools: The case of the talanoa and the faafaletui in Samoa. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 55(3), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12061

- Weiss, N. M. (2021). A critical perspective on syndemic theory and social justice. Public Anthropologist, 3(2), 285–317. https://doi.org/10.1163/25891715-bja10022

- Wendt, S. (2008). Christianity and domestic violence: Feminist poststructuralist perspectives. Affilia, 23(2), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109908314326

- Whitesell, N. R., Mousseau, A., Parker, M., Rasmus, S., & Allen, J. (2020). Promising practices for promoting health equity through rigorous intervention science with indigenous communities. Prevention Science, 21(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0954-x

- Zanotti, L., Carothers, C., Apok, C. A., Huang, S., Coleman, J., & Ambrozek, C. (2020). Political ecology and decolonial research: Co-production with the Iñupiat in Utqiaġvik. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.2458/v27i1.23335