ABSTRACT

International evidence suggests migrants experience significant cancer inequities. In Australia, there is limited information assessing equity for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) migrant populations, particularly in cancer prevention. Cancer inequities are often explained by individualistic, behavioural risk factors; however, scarce research has quantified or compared engagement with cancer prevention strategies. A retrospective cohort study was conducted utilising the electronic medical records at a major, quaternary hospital. Individuals were screened for inclusion in the CALD migrant or Australian born cohort. Bivariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression were used to compare the cohorts. 523 individuals were followed (22% were CALD migrants and 78% Australian born). Results displayed that CALD migrants made up a larger proportion of infection-related cancers. Compared to Australian born, CALD migrants had lower odds of having a smoking history (OR = 0.63, CI 0.401–0.972); higher odds of ‘never drinking’ (OR = 3.4, CI 1.473–7.905); and lower odds of having breast cancers detected via screening (OR = 6.493, CI 2.429–17.359). Findings affirm CALD migrants’ low participation in screening services but refute the assertion that CALD migrants are less engaged in positive health practices, enabling cancer prevention. Future research should examine social, environmental, and institutional processes and move beyond individualistic, behavioural explanations for cancer inequities.

Introduction

Cancer is a significant and increasing global health concern, for which burden and outcomes are not equitably distributed across regions, countries, or populations (Prager et al., Citation2018). Health inequities refer to health differences which are ‘avoidable, unnecessary and unjust’ and are influenced by an interplay of social, structural, and economic determinants (Braveman, Citation2014; Fidler et al., Citation2018; Viruell-Fuentes et al., Citation2012; Whitehead, Citation1992). Historically, cancer has been overrepresented in high-income countries due to the relatively higher prevalence of non-communicable diseases (Vineis & Wild, Citation2014). However, cancer is now considered an emerging epidemic in low-middle income countries (LMIC’s), which are now experiencing high rates of communicable disease as well as a growing trend towards non-communicable diseases, predisposing them to cancers of both infectious and non-infectious origins (Armin & Eichelberger, Citation2019; Vineis & Wild, Citation2014; Yu et al., Citation2022). These regional variations of cancer burden have implications for migrant populations, particularly those from LMIC’s, whose unique needs and risk factors may not be reflected in the new health systems, policies, or prevention strategies that they are reliant on (Phillips et al., Citation2016; J. Shaw et al., Citation2013). There is strong international evidence demonstrating cancer-related disparities among migrant and ethnic minority populations (Foster, Citation2015; Thomas et al., Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2019). Causes of these disparities include structural barriers across the cancer care continuum, including challenges with access and navigation (Hilder et al., Citation2019). These challenges may be compounded by factors such as social marginalisation, institutional racism and weakened social networks in post-migratory settings (Barnett et al., Citation2021; J. M. Shaw et al., Citation2016; Tan et al., Citation2021).

In Australia, there is limited information assessing equitable health outcomes for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) populations, defined in this study as those born in a country or region outside of Australia, where English is not the primary language (Pham et al., Citation2021). Available evidence suggests that CALD migrants experience disparities in access to cancer screening services (Wang et al., Citation2019), as well as poorer treatment quality and quality of life (Ming et al., Citation2015; Sze et al., Citation2015). Barriers faced by CALD populations have been reported as unmet physical and informational needs, as well as structural barriers such as time constraints and a lack of culturally-appropriate resources within health services (I. Alananzeh et al., Citation2018; I. M. Alananzeh et al., Citation2019; Butow et al., Citation2013; Scanlon et al., Citation2021). A recent systematic scoping review revealed a dearth of information spanning the cancer care continuum, particularly in the critical stage of prevention (Scanlon et al., Citation2021). This review found that only 3% of included studies assessed cancer prevention, compared with 31% assessing detection (Scanlon et al., Citation2021). Included prevention studies examined presence of hepatitis B (HBV) and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infections for the prevention of liver and gastric cancers respectively (Robotin et al., Citation2010; Schulz et al., Citation2014). In Australia, HBV screening is recommended for priority CALD populations in order to reduce the risk of virus transmission and cancer development, as well as promote linkage to care (National Hepatitis B Testing Policy, Citation2020, Citation2020). Along with exposures to infectious agents, other modifiable risk factors commonly associated with cancer development include tobacco use, alcohol consumption, diet, exercise, and Body Mass Index (BMI) (Curtin et al., Citation2021; ‘National Cancer Control Indicators: Prevention’, Citation2021).

Despite a lack of substantial evidence regarding individual health behaviours and prevention practices among CALD migrant populations, Australian research and health policies for prevention of cancer and other chronic diseases remain focused on individualistic, behavioural factors (‘Cancer doesn't discriminate by culture – nor should we’, Citation2012; Curtin et al., Citation2021). This places cancer prevention and responsibility onto individuals, ignoring the social, economic, and structural causes of disparities (‘Cancer doesn't discriminate by culture – nor should we’, Citation2012; Curtin et al., Citation2021; Scanlon et al., Citation2021). These deficit-based explanations of disparities are evident in Australian research, which has stated CALD migrant populations are ‘less likely to be pro-active in accessing healthcare or undertaking preventative health initiatives’ (Caperchione et al., Citation2009, Caperchione et al., Citation2013), or that health promotion and disease prevention are ‘low priorities’ for ethnically diverse women (Gettleman & Winkleby, Citation2000). Research which perpetuates these assumptions risk reproducing uncritical health policies, and strengthen existing generalisations and biases held by some healthcare workers (Kumas-Tan et al., Citation2007). This increases the potential for culturally incompetent policies which allow disparities to persist and widen (Hyatt et al., Citation2017). Critically, this approach ignores the root causes of health disparities, related to the social determinants of health, including institutional inaccessibility and racism (Curtin et al., Citation2021; McLeroy et al., Citation1988).

Unlike prevention, there is substantially more research available regarding cancer detection for CALD migrant populations, often measured as screening participation (Scanlon et al., Citation2021). Australian research has consistently demonstrated CALD migrant populations are less likely to participate in cervical, bowel and breast screen services (Lam et al., Citation2018; Phillipson et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation2001). Screening is the most researched stage of the cancer care continuum in Australia, displaying an over-reliance on screening as a proxy measure of equity (Scanlon et al., Citation2021). This is inadequate, firstly, because screening is usually considered an early detection method rather than prevention and secondly, there are currently only three National Screening Programmes in Australia (‘Early Detection and Screening’, Citation2022; ‘Screening for cancer’, Citation2022).

Despite limited research, prevention has the greatest potential for reducing cancer inequities (Vineis & Wild, Citation2014). Other benefits include the reduction of morbidity, mortality, and overall cost to the healthcare system (Vineis & Wild, Citation2014). This is particularly relevant in health systems with resource scarcity, an increasingly common and widespread occurrence during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bakouny et al., Citation2020; Chiriboga et al., Citation2020). Critical to reducing disparities is testing equity indicators to quantify and compare areas of potential inequity (‘National Cancer Control Indicators’, Citation2021). This retrospective cohort study responds to the need for increased prevention-focused cancer research, thus providing some of the evidence necessary for the promotion and operationalisation of health equity.

Methods

Study design, population, and setting

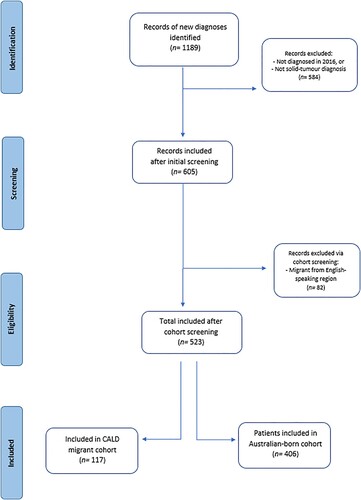

A retrospective cohort study was conducted, using the electronic medical records at a major quaternary hospital in Queensland, Australia. This hospital is the largest public hospital and cancer care service in Queensland, with 2019 data revealing it provided over 150,000 cancer treatments, admissions and consultations (‘Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital: About us’, Citation2020). The study was undertaken to investigate equity in the stages of cancer prevention and detection. Inpatient and outpatient encounters were assessed for all individuals diagnosed with a solid tumour cancer in the year 2016. Participants were followed for a total of five years post diagnosis, or until patient death. The inclusion criteria required participants to be: (1) diagnosed with a solid tumour malignancy, (2) ≥ 16 years of age at diagnosis. Participants were then disaggregated based on country of birth. Those born in Australia were included in the ‘Australian born’ cohort, regardless of their parents’ backgrounds, and those born outside of Australia were assessed for the ‘CALD-migrant’ cohort. Individuals born in a country or region outside of Australia, where English was not the primary language were included in the ‘CALD-migrant’ cohort. Māori, the indigenous Polynesian people of Aotearoa/New Zealand were included in the CALD cohort, due to cultural and often, linguistic diversity. Those who had migrated from countries or regions where English was the primary language and the participants’ primary language was also English, such as England, were excluded from the study. The screening process for this study is displayed in . Ethical approval for this study was sought and obtained by the facility prior to commencing data collection: (HREC/2021/QRBW/74613).

Data collection tools and variables

A data collection tool was created based on the National Cancer Control Indicators (NCCIs), developed by Cancer Australia (‘National Cancer Control Indicators’, Citation2021). The NCCIs were used in the absence of standardised equity indicators for cancer care. These indicators are clinical measures that signify an individual’s disease status and significant treatment outcomes. There is a range of clinical indicators, which span each stage of the cancer care continuum (‘National Cancer Control Indicators’, Citation2021). These indicators have been used to highlight disparities in populations such as First Nations Australian’s, who also experience cancer inequities, but this is the first study where these indicators have been used for CALD migrant populations (‘National Cancer Control Indicators’, Citation2021). The indicators used in this study are those associated with prevention and detection, shown in . In addition to the NCCI’s, a range of socio-demographic variables were collected based on data availability within the electronic medical records. These variables are presented in .

Table 1. National Cancer Control Indicators for prevention and detection.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 26 (‘IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26’, Citation2021). Categorical variables were summarised as proportions and percentages. The Chi Square test was utilised to determine associations between categorical variables, except where the cell size was ≤5, in which Fisher’s Exact Test was applied. Continuous variables were examined using a t-test for normally distributed data and Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data and were reported as means and standard deviation. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bivariate analysis was performed to identify associations between the cohorts and the NCCIs. Bivariate analysis was also performed to identify associations between sociodemographic variables and the NCCIs. Factors found to be associated with prevention or detection NCCIs in this bivariate analysis (P = <0.1) were then included in multivariate logistic regression models.

Results

Participant screening and characteristics

As displayed in , a total of 1189 participants were screened over a three-month period (1st August 2021–1st November 2021); of whom 523 were included within the study. The majority (>80%) of those excluded were excluded on the basis of having a solid tumour malignancy diagnosed prior to the year 2016, or being diagnosed with a condition other than a solid tumour malignancy. Of those included, 117 (22%) were in the CALD migrant cohort and 406 (78%) were in the Australian born cohort. The mean age of participants was 59 years (SD = 13.4). Nearly 56% were female, with more females in the CALD migrant cohort (65.8%) than the Australian born cohort (52.7%). For those not born in Australia the most common regional backgrounds were Asia (31.6%), Europe (31.6%) and Polynesia (26.5%). There were several tumour streams in which CALD migrants made up a higher proportion of participants. This included Breast (30% vs 19%), Lung (13% vs 11%), Upper GI (14% vs 10%) and Gynae-oncology (14% vs 9%). This was also evident in subgroup analysis, that displayed multiple cancer types in which CALD migrants were a higher proportion. Most notably, Cervical (5% vs 3%), Gastric (6% vs 1%) and Endometrial (3% vs 1%). All participants’ medical records were searched from date of diagnosis, with a total of five years’ follow-up, or until patient death. Data were largely complete with only 8 (1.5%) participants having incomplete or multiple missing variables.

Primary prevention

As displayed in , bivariate analysis indicated that the Australian born cohort had a statistically significantly higher chance of a smoking history than CALD migrants (64% vs 49%; P = 0.003). Alcohol consumption was also higher in the Australian born cohort, with the largest proportion of CALD migrants ‘never’ drinking alcohol (60% vs 40%) and those born in Australia significantly more likely to have ‘multiple drinks daily’ (30% vs 10%; P = 0.027). Both cohorts displayed a high proportion of participants in the ‘healthy weight’ category, although CALD migrants were more frequently ‘underweight’ (18% vs 8%) and Australian born were more frequently ‘obese’ (11% vs 6%; P = 0.013). As displayed in , multivariate logistic regression was undertaken for NCCIs and sociodemographic variables with significant associations. Sex, religion, employment, and marital status were adjusted for as indicated. Having a smoking history was associated with CALD status. Compared to those born in Australia, CALD migrants had 37% lower odds of having a smoking history (OR = 0.63, CI 0.40–0.97), when controlled for employment, religion, and sex. There was a strong association found between employment and smoking history, with the odds of an unemployed person having a smoking history 2.4 times higher than those employed (CI 1.23–4.76). Alcohol consumption was also associated with CALD status. Compared to those born in Australia, CALD migrants’ odds of ‘never drinking’ were 3.4 times higher than those born in Australia (CI 1.473–7.905), when controlled for sex, religion, employment, and marital status. The indicator of BMI was not included in the logistic regression, as it was not significantly associated with any sociodemographic variables.

Table 3. Bivariate analysis of prevention indicators.

Table 4. Logistic regression for prevention indicators.

Detection

Detection was measured using the NCCI of screening participation (‘National Cancer Control Indicators’, Citation2021). As such, data were analysed for the three cancers with current National Screening Programmes in Australia; Breast, Bowel and Cervical (‘Screening for cancer’, Citation2022). As displayed in , Fishers Exact Test was used to determine if there were statistically significant differences in the use of screening services for cancer detection between the cohorts. There were differences found between the two cohorts in all three cancers, and breast cancer was found to be statistically significant. For those with breast cancer, 34% (n = 12) of CALD migrants were screen detected, as opposed to 70% (n = 53) of the Australian born cohort (P = <0.001). Similarly, in bowel cancer, 11% (n = 1) of CALD migrants were screen detected as opposed to 43% (n = 16) of Australian born participants, however, these results were not statistically significant (P = 0.075). For cervical cancer, 33% (n = 2) of CALD migrants were screen detected, whereas 82% (n = 9) of Australian born participants were detected via screening, these results were not statistically significant (P = 0.072).

Table 5. Bivariate analysis for detection indicators.

As displayed in , multivariate logistic regression was undertaken for screening in breast cancer participants and the associated sociodemographic variables. This displayed that after adjusting for religion and employment, the odds of an Australian born participant having their breast cancer detected via screening was 6.5 times higher than CALD migrants (CI 2.429–17.359).

Table 6. Logistic regression for detection indicator.

Discussion

This exploratory, descriptive study sought to quantify equity indicators, with a focus on cancer prevention and detection for CALD migrant populations. The study demonstrates the critical need for prevention focused cancer research. The study had three key findings. Firstly, CALD migrant populations exhibited similar, and often more favourable health behaviours than their Australian born counterparts, being less likely to drink heavily or have a smoking history. Secondly, CALD migrant populations were significantly less likely to have their breast cancer detected via screening services. Thirdly, CALD migrants made up a larger proportion of cancers associated with infectious agents. These findings are important because current cancer prevention strategies focus heavily on modifiable risk factors and poorly defined ‘cultural’ explanations of cancer inequities (Broom et al., Citation2020; Suwankhong & Liamputtong, Citation2018). However, the results from this study suggest individual health behaviours may not be the most significant contributor to cancer-related disparities, highlighting access to screening services and exposure to infectious agents as potential contributors (Lam et al., Citation2018; Elizabeth Ortiz et al., Citation2020).

The first finding has several implications for public health. It suggests targeted prevention strategies which position CALD communities as ‘less healthy’ or having less healthy ‘lifestyle’ factors than those born in Australia may be ineffective and may potentially contribute to cultural stereotyping (Alqahtani et al., Citation2020; Geiger, Citation2001). This can further entrench cultural biases and fuel social and institutional racism (Dune & Williams, Citation2021; Shinagawa, Citation2000). Secondly, behavioural explanations direct blame and responsibility on to individuals for health outcomes which may be beyond their control (Curtin et al., Citation2021). These explanations disproportionately impact marginalised groups and mask the social, environmental, and institutional contexts where cancer is produced and inequities are reproduced (Curtin et al., Citation2021; Fries, Citation2020; McLeroy et al., Citation1988; Scanlon et al., Citation2021). This signifies the need for strength-based approaches to cancer prevention initiatives and research.

The second finding concurs with current evidence that CALD migrant populations are significantly less likely to have their cancer detected via screening services (Lam et al., Citation2018; Phillipson et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation2001). This was displayed in all three screen-detectable cancers, however, in this study, only breast cancer was statistically significant. This is important because screening can increase early detection, timely linkage to care and ultimately, improve survival (Warner et al., Citation2012). This study postulates that due to the differences between the stages of prevention and detection, inequities for CALD migrants may be due to institutional (in)accessibility rather than individual health behaviours. This warrants further research and underscores the need to examine the multiple, intersecting dimensions that produce inequities (Curtin et al., Citation2021; Viruell-Fuentes et al., Citation2012).

Thirdly, CALD migrants displayed a higher proportion of cancers associated with infectious agents, with higher proportions of gastric and cervical cancers. This is significant, as evidence suggests migrants from hepatitis B virus (HBV), Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and human papillomavirus (HPV) endemic countries are not routinely screened for these infectious agents when they migrate to Australia, often relying on opportunistic testing (‘Clinical Guidelines’, Citation2022; E. Ortiz et al., Citation2020; ‘People from Culturally and Linguistically Divserse Backgrounds’, Citation2022). This is an important oversight given these infectious agents are strongly linked to increased cancer risk (E. Ortiz et al., Citation2020). Therefore, in order to achieve equity in cancer prevention among migrant populations, it is necessary that high-income countries, such as Australia, incorporate an understanding of pre-migratory epidemiology into screening services (E. Ortiz et al., Citation2020). Screening is a necessary public health measure, underscored by the often asymptomatic nature of these infectious agents. This increases the potential of transmission throughout communities vulnerable to these agents, further perpetuating cancer and health inequities (E. Ortiz et al., Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2022).

It is imperative to acknowledge the role that previous research has played in fostering assumptions and influencing health policy, through perpetuating the narrative that disease prevention practices are ‘low priorities’ for CALD migrant populations (Caperchione et al., Citation2009; Gettleman & Winkleby, Citation2000). Indeed, the Australian Cancer Council states that CALD Australians have lower participation in both prevention and screening programmes, which may be misleading given the positive prevention practices identified in this study (‘Cancer doesn't discriminate by culture – nor should we’, Citation2012). Research which perpetuates these narratives risk reproducing incorrect, racialised assumptions throughout future research and policies.

In order to operationalise health equity, research must move beyond simply describing inequities and examine the underlying causes (Roberson, Citation2022). To date, Australian research has utilised screening participation as a proxy measure for equity (Scanlon et al., Citation2021). This study demonstrated several areas in need of further research, such as the intersection of social, structural and environmental determinants. This is necessary in order to illuminate areas of inequity that require targeted solutions, without relying on culturally biased assumptions (Dune & Williams, Citation2021; Loos, Citation1995). Therefore, whilst findings from this study are beneficial, they should be considered a first step in addressing the issues of inequity in cancer prevention and detection.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. Firstly, this study was exploratory and descriptive, based on routinely collected data, making a retrospective cohort study appropriate. The design enabled timely data collection, a total of five years’ follow up and allowed for relatively complete data collection. The findings from this study justify a multi-site, prospective cohort study in the future. To reduce the risk of selection bias and increase sample size, the entire cohort of new diagnoses from the year 2016 were screened for inclusion, rather than a smaller sample.

Limitations include a relatively small sample size, which did not allow for adequate subgroup analysis, potentially undermining internal and external validity. Additionally, this small sample size affects the power of the statistical analysis, as displayed by the wide confidence intervals in the results. A larger, multi-site study is suggested for confirmation of these results. Secondly, the study relied on routine data collected via the medical records, which can be imprecise or inaccurate due to human error. This risk was mitigated through cross checking variables across multiple forms of documentation. The results are reflective of a sample taken from a single-site quaternary hospital and may not be generalisable or able to be further extrapolated to the Queensland, or wider Australian population. The single-site of data collection may have affected the study participants and selection bias cannot be excluded. However, the site utilised was the largest public hospital in Queensland which offers the key specialist cancer services for the state, and was therefore the most representative site for a single-center analysis. A multi-site study is recommended in the future. As the screening sample was taken from referrals made into cancer care services, it is acknowledged that the overall sample may have excluded some individuals with early-stage malignancies who were treated with surgical intervention and did not receive further systemic therapies. It must also be acknowledged that this quaternary hospital is in an inner metropolitan location, and that <10% of the CALD migrant cohort resided in rural or regional locations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has provided novel insights into the fields of cancer prevention and detection for CALD migrant populations in Queensland, Australia. Findings support current evidence which indicates that CALD migrant populations are significantly less likely to have their cancers diagnosed via screening services, but postulates that this may be reflective of structural and institutional determinants, rather than individual health behaviours. Further, this study has demonstrated CALD migrant populations exhibit similar or more favourable health practices associated with cancer prevention. This is discordant with previous cancer research and the dominant cancer prevention narrative that implies CALD migrant populations are less engaged in cancer prevention practices. The study also revealed that CALD migrant populations are overrepresented in infection-related cancers, affirming the need for increased screening for migrants from HBV, HPV and H. Pylori endemic countries, to assist with cancer prevention. In order to achieve health equity, it is imperative that cancer prevention research shifts to a strength-based approach that is reflective of social, environmental, and institutional determinants, rather than perpetuating deficit-based explanations that fuel cultural stereotypes, institutional racism, and ultimately do not address health inequities.

Ethics approval

(HREC/2021/QRBW/74613)

Author contributors

BS conducted the cohort study under the guidance of JD and DW. BS and GT conducted the statistical analysis. BS was the major contributor to the manuscript writing, with feedback from JD, DW, GT and NR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request: [email protected]

References

- Alananzeh, I., Ramjan, L., Kwok, C., Levesque, J. V., & Everett, B. (2018). Arab-migrant cancer survivors’ experiences of using health-care interpreters: A qualitative study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 5(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_19_18

- Alananzeh, I. M., Kwok, C., Ramjan, L., Levesque, J. V., & Everett, B. (2019). Information needs of Arab cancer survivors and caregivers: A mixed methods study. Collegian, 26(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.001

- Alqahtani, N. M., Shehata, S. F., & Mostafa, O. A. (2020). Prevalence and determinants of unconscious stereotyping among primary care physicians. Saudi Medical Journal, 41(8), 858–865. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2020.8.25186

- Armin, J. B., & Eichelberger, L. (2019). Negotiating structural vulnerability in cancer control. University of New Mexico Press.

- Bakouny, Z., Hawley, J. E., Choueiri, T. K., Peters, S., Rini, B. I., Warner, J. L., & Painter, C. A. (2020). COVID-19 and cancer: Current challenges and perspectives. Cancer Cell, 38(5), 629–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2020.09.018

- Barnett, M. L., Luis Sanchez, B. E., Green Rosas, Y., & Broder-Fingert, S. (2021). Future directions in Lay health worker involvement in children's mental health services in the U.S. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(6), 966–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2021.1969655

- Braveman, P. (2014). What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl 2), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S203

- Broom, A., Parker, R., Raymond, S., Kirby, E., Lewis, S., Kokanovic, R., … Koh, E. S. (2020). The (Co)Production of difference in the care of patients With cancer from migrant backgrounds. Qualitative Health Research, 30(11), 1619–1631. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320930699

- Butow, P. N., Bell, M. L., Aldridge, L. J., Sze, M., Eisenbruch, M., Jefford, M., & Psycho-Oncology Co-operative Research Group, C. t (2013). Unmet needs in immigrant cancer survivors: A cross-sectional population-based study. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(9), 2509–2520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1819-2

- Caperchione, C. M., Kolt, G. S., & Mummery, W. K. (2009). Physical activity in culturally and linguistically diverse migrant groups to western society: A review of barriers, enablers and experiences. Sports Medicine, 39(3), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200939030-00001

- Caperchione, C. M., Kolt, G. S., & Mummery, W. K. (2013). Examining physical activity service provision to culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities in Australia: A qualitative evaluation. PLoS One, 8(4), e62777. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062777

- Chiriboga, D., Garay, J., Buss, P., Madrigal, R. S., & Rispel, L. C. (2020). Health inequity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cry for ethical global leadership. The Lancet, 395(10238), 1690–1691. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31145-4

- Clinical Guidelines. (2022). https://www.hepatitisaustralia.com/clinical-guidelines.

- Croager, Emma. (2012). https://www.cancer.org.au/blog/cancer-doesnt-discriminate-by-culture-nor-should-we.

- Curtin, K. D., Thomson, M., & Nykiforuk, C. I. J. (2021). Who or what is to blame? Examining sociodemographic relationships to beliefs about causes, control, and responsibility for cancer and chronic disease prevention in Alberta, Canada. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1047. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11065-4

- Dune, T. M., & Williams, R. (2021). Culture, diversity and health in Australia. Towards culturally safe health care (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Early Detection and Screening. (2022). https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/causes-and-prevention/early-detection-and-screening.

- Fidler, M. M., Bray, F., & Soerjomataram, I. (2018). The global cancer burden and human development: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817715400

- Foster, S. (2015). Cancer health disparities in the United States: Facts & figures. https://www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/health_disparities_fact_sheet.pdf.

- Fries, C. J. (2020). The medicalization of cancer as socially constructed and culturally negotiated. Health Promotion International, 35(6), 1543–1550. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa004

- Geiger, H. J. (2001). Racial stereotyping and medicine: The need for cultural competence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 164(12), 1699–1700. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11450212.

- Gettleman, L., & Winkleby, M. A. (2000). Using focus groups to develop a heart disease prevention program for ethnically diverse, low-income women. Journal of Community Health, 25(6), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005155329922

- Hilder, J., Gray, B., & Stubbe, M. (2019). Health navigation and interpreting services for patients with limited English proficiency: A narrative literature review. Journal of Primary Health Care, 11(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC18067

- Hyatt, A., Lipson-Smith, R., Schofield, P., Gough, K., Sze, M., Aldridge, L., … Butow, P. (2017). Communication challenges experienced by migrants with cancer: A comparison of migrant and English-speaking Australian-born cancer patients. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 20(5), 886–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12529

- IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26. (2021). https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_26.0.0/pdf/en/Accessibility.pdf.

- Kumas-Tan, Z., Beagan, B., Loppie, C., MacLeod, A., & Frank, B. (2007). Measures of cultural competence: Examining hidden assumptions. Academic Medicine, 82(6), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555a2d

- Lam, M., Kwok, C., & Lee, M.-J. (2018). Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of routine breast cancer screening practices among migrant-Australian women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42(1), 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12752

- Loos, G. P. (1995). Foldback analysis: A method to reduce bias in behavioral health research conducted in cross-cultural settings. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049500100406

- McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

- Ming, S., Butow, P., Bell, M., Vaccaro, L., Dong, S., Eisenbruch, M., … Goldstein, D. (2015). Migrant health in cancer: Outcome disparities and the determinant role of migrant-specific variables. The Oncologist, 20(5), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0274

- National Cancer Control Indicators. (2021a). https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/.

- National Cancer Control Indicators: Prevention. (2021b). https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/prevention.

- National Hepatitis B Testing Policy 2020. (2020). https://testingportal.ashm.org.au/files/ASHM_TestingPolicy_2020_HepatitisB_07_2.pdf.

- Ortiz, E., Scanlon, B., Mullens, A., & Durham, J. (2020). Effectiveness of interventions for hepatitis B and C: A systematic review of vaccination, screening, health promotion and linkage to care within higher income countries. Journal of Community Health, 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00699-6

- People from Culturally and Linguistically Divserse Backgrounds. (2022). https://testingportal.ashm.org.au/national-hbv-testing-policy/people-from-culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-backgrounds/.

- Pham, T. T. L., Berecki-Gisolf, J., Clapperton, A., O'Brien, K. S., Liu, S., & Gibson, K. (2021). Definitions of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD): A literature review of epidemiological research in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020737

- Phillips, C., Fisher, M., Baum, F., MacDougall, C., Newman, L., & McDermott, D. (2016). To what extent do Australian child and youth health policies address the social determinants of health and health equity?: A document analysis study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 512. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3187-6

- Phillipson, L., Pitts, L., Hall, J., & Tubaro, T. (2019). Factors contributing to low readiness and capacity of culturally diverse participants to use the Australian national bowel screening kit. Public Health Research & Practice, 29(1), 28231810. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp28231810

- Prager, G. W., Braga, S., Bystricky, B., Qvortrup, C., Criscitiello, C., Esin, E., … Ilbawi, A. (2018). Global cancer control: Responding to the growing burden, rising costs and inequalities in access. ESMO Open, 3(2), e000285. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000285

- Roberson, M. L. (2022). Let's get critical: Bringing critical race theory into cancer research. Nature Reviews Cancer, 22(5), 255–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00453-6

- Robotin, M. C., Kansil, M. Q., George, J., Howard, K., Tipper, S., Levy, M., … Penman, A. G. (2010). Using a population-based approach to prevent hepatocellular cancer in New South Wales, Australia: Effects on health services utilisation. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 215–215. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-215

- Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital: About us. (2020). https://metronorth.health.qld.gov.au/rbwh/about-us.

- Scanlon, B., Brough, M., Wyld, D., & Durham, J. (2021). Equity across the cancer care continuum for culturally and linguistically diverse migrants living in Australia: A scoping review. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00737-w

- Schulz, T. R., McBryde, E. S., Leder, K., & Biggs, B.-A. (2014). Using stool antigen to screen for Helicobacter pylori in immigrants and refugees from high prevalence countries is relatively cost effective in reducing the burden of gastric cancer and peptic ulceration. PloS one, 9(9), e108610–e108610. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108610

- Screening for cancer. (2022). https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/cancer/screening-for-cancer.

- Shaw, J., Butow, P., Sze, M., Young, J., & Goldstein, D. (2013). Reducing disparity in outcomes for immigrants with cancer: A qualitative assessment of the feasibility and acceptability of a culturally targeted telephone-based supportive care intervention. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(8), 2297–2301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1786-7

- Shaw, J. M., Shepherd, H. L., Durcinoska, I., Butow, P. N., Liauw, W., Goldstein, D., & Young, J. M. (2016). It's all good on the surface: Care coordination experiences of migrant cancer patients in Australia. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(6), 2403–2410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3043-8

- Shinagawa, S. M. (2000). The excess burden of breast carcinoma in minority and medically underserved communities: Application, research, and redressing institutional racism. Cancer, 88(5 Suppl), 1217–1223. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000301)88:5+<1217::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-K

- Suwankhong, D., & Liamputtong, P. (2018). Early detection of breast cancer and barrier to screening programmes amongst Thai migrant women in Australia: A qualitative study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP, 19(4), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.1089

- Sze, M., Butow, P., Bell, M., Vaccaro, L., Dong, S., Eisenbruch, M., & Linguistically Diverse, T (2015). Migrant health in cancer: Outcome disparities and the determinant role of migrant-specific variables. The Oncologist, 20(5), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0274

- Tan, S. T., Low, P. T. A., Howard, N., & Yi, H. (2021). Social capital in the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases among migrants and refugees: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Global Health, 6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006828

- Taylor, R. J., Mamoon, H. A., Morrell, S. L., & Wain, G. V. (2001). Cervical screening in migrants to Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00551.x

- Thomas, B. C., Carlson, L. E., & Bultz, B. D. (2009). Cancer patient ethnicity and associations with emotional distress—the 6th vital sign: A New look at defining patient ethnicity in a multicultural context. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 11(4), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-008-9180-0

- Vineis, P., & Wild, C. P. (2014). Global cancer patterns: Causes and prevention. The Lancet, 383(9916), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62224-2

- Viruell-Fuentes, E. A., Miranda, P. Y., & Abdulrahim, S. (2012). More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science & Medicine, 75(12), 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037

- Wang, A. M. Q., Yung, E. M., Nitti, N., Shakya, Y., Alamgir, A. K. M., & Lofters, A. K. (2019). Breast and colorectal cancer screening barriers Among immigrants and refugees: A mixed-methods study at three community health centres in Toronto, Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(3), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0779-5

- Warner, E. T., Tamimi, R. M., Hughes, M. E., Ottesen, R. A., Wong, Y. N., Edge, S. B., … Partridge, A. H. (2012). Time to diagnosis and breast cancer stage by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 136(3), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2304-1

- Whitehead, M. (1992). The concepts and principles of equity and health. International Journal of Health Services, 22(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN

- Yu, X. Q., Feletto, E., Smith, M. A., Yuill, S., & Baade, P. D. (2022). Cancer incidence in migrants in Australia: Patterns of three infection-related cancers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-1349