Abstract

India has the highest global burden of tuberculosis (TB), accounting for a quarter of the worldwide TB disease incidence. Given the magnitude of India’s epidemic, TB has enormous economic implications. Indeed, the majority of individuals with TB disease are in their prime years of economic productivity. Absenteeism and employee turnover due to TB have economic ramifications for employers. Furthermore, TB can easily spread in the workplace and compound the economic impact. Employers who fund workplace, community, or national TB initiatives stand to gain directly and also enjoy reputational benefits, which are important in the era of socially conscious investing. Corporate social responsibility laws in India and tax incentives can be leveraged to bring the logistical networks, reach, and innovative spirit of the private sector to bear on India’s formidable TB epidemic. In this perspective piece, we explore the economic impacts of TB; opportunities for and benefits from businesses contributing to TB elimination efforts; and strategies to enlist India’s corporate sector in the fight against TB.

Introduction

With 1.5 million deaths worldwide in 2020, tuberculosis (TB) is the leading infectious killer after coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) (World Health Organization, Citation2021b). After infection with the airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a minority of individuals develop active disease, but the majority develop asymptomatic infections. Approximately 5-10% of individuals with asymptomatic infections progress to active TB disease later in life (Pai et al., Citation2016). India bears a quarter of the global TB burden, with 2.7 million cases and approximately 400,000 deaths annually (World Health Organization, Citation2021a). India’s TB epidemic has substantial economic repercussions for both individuals and corporations due to lost productivity, worker absenteeism, employee turnover, and workplace infection (Garba, Citation2017). The estimated costs from TB absenteeism alone in India are $300 million/year (‘Combating Drug-Resistant TB Through Public–Private Collaboration and Innovative Approaches,”, Citation2012).

India’s national strategic plan was oriented towards an audacious goal of eliminating TB in India by 2025, ahead of the global TB elimination goals outlined in the End-TB strategy (National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis:, Citation2017–Citation25 - Elimination by Citation2025, Citation2017). The Indian government increased the budget for National TB Elimination Programme (NTEP), enacted patient-centric programmes such as Nikshay Poshan Yojana and the TB Mitra programme, and engaged the private sector through public-private mix (PPM) strategies.

The private sector plays an essential role in TB care. Of the people treated by the NTEP, approximately 65% first receive care in the private sector (Veesa et al., Citation2018). A modelling study that tracked antituberculosis therapy prescriptions in India concluded that twice as much TB treatment occurred in the private sector compared to the public sector (Arinaminpathy et al., Citation2016). Engaging the private sector is critical to TB elimination in India, but the focus in PPM tends to be on private sector providers providing TB care. Although engaging corporate entities is a recognised component of PPM strategies, we believe that the full potential of Indian corporate entities has not been harnessed hitherto.

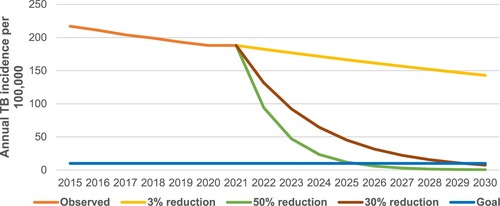

Despite the Indian government’s commendable commitment, reductions in TB incidence and mortality are falling short of the required trajectory to attain TB elimination goals (Pai et al., Citation2017). Since 2015, the annual decline in TB incidence in India has been less than 3% per annum – in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic – whereas the required rate to achieve the End TB strategy goal (incidence <10 per 100,000) by 2025 and 2030 would be approximately 50% per annum and 30% per annum, respectively (). New strategies and tools are needed to achieve such rapid declines. Engaging corporate entities, not just private sector healthcare providers, in the fight to eliminate TB could galvanise India’s TB elimination campaign while also benefitting corporations.

Figure 1. Observed reduction in TB incidence in India and projections assuming TB elimination rates of 3% per annum, 30% per annum, and 50% per annum envisaging rapid reductions in TB incidence to attain End-TB strategy goals (incidence <10 per 100,000) by 2025 and 2030 respectively.

The success of involving corporations in infectious disease control has already been observed with corporate involvement in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired-immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) prevention and treatment, particularly when corporate social responsibility is done in tandem with both national governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (“Business Sector Can Play Key Role in the AIDS Response in Africa,”, Citation2011). Some businesses have funded HIV education and awareness campaigns in the workplace and local communities, while others have instituted workplace HIV/AIDS testing initiatives and provided treatment support for employees with HIV infection (Petkoski & Kersemaekers, Citation2003).

To explore the possibilities of corporate engagement for TB elimination in India, we hosted a symposium at the 65th Indian Public Health Association Conference in 2021 with speakers from the Indian government, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), academia, and NGOs. The symposium was attended by more than 400 participants. It used a systems approach of understanding that population health and socio-economic health of a community are inextricably linked, and involved participants from a wide variety of sectors in this form of systems thinking. In this paper, we will distill insights from the symposium regarding the impacts of TB on businesses, opportunities for companies to contribute to TB elimination efforts, and the benefits to businesses from engagement in TB elimination efforts.

Impact of TB on employees and employers

Absenteeism from work and loss of employment

TB largely affects people in the prime of their economic lives, with 65% of people with TB (PWTB) in India aged between 15 and 45 (“Citation65% of TB Cases in India in Citation15–Citation45 Age Group: Health Minister,”, Citation2021), thus affecting both the household of the PWTB and the larger economy. Indirect costs due to lost wages eclipse the direct costs of diagnosis and treatment (Sinha et al., Citation2020). These indirect costs include wages lost by the caretakers of PWTB who often also miss work (Sinha et al., Citation2020).

Substantial numbers of PWTB miss work due to their TB disease, both due to the symptoms of the disease and in often-lengthy delays in diagnosis. A 2005 study in Tamil Nadu found that 46% of PWTB missed work during TB treatment, with 12% missing more than 60 days and an additional 12% not returning to work at the end of their treatment (Muniyandi et al., Citation2005). Similar trends have been noted in other parts of India (Pantoja et al., Citation2009; Ray et al., Citation2005; Sinha et al., Citation2020). With rapid diagnosis and treatment initiation, many PWTB can return to work within 2–4 weeks of initiating treatment (Maher et al., Citation2003). However, delays in diagnosis driven by hesitation to seek testing due to stigma or lack of awareness, coupled with tortuous diagnostic journeys and incomplete adherence often lead to treatment failure, meaning that workers may be absent for longer periods (Sinha et al., Citation2020).

Employers whose workers are temporarily absent from their positions need to adjust their operations to accommodate a smaller staff, and employers who lose workers permanently must hire and train new employees. Losing experienced employees diminishes the human capital of businesses and may make them less efficient. Hiring and training new employees may result in higher costs than would occur from workplace programmes to prevent TB. In the midst of the so-called ‘great resignation’ happening in India, the US, and other countries around the world and in which many workers are leaving their jobs due to both COVID-19 and changes in the labour market, employers may find it even more difficult to fill the positions of sick employees and may suffer lengthier workforce shortages due to TB (Anand, Citation2022; Fuller & Kerr, Citation2022).

Furthermore, despite successful treatment, a large proportion of TB survivors experience chronic lung disease that can limit their physical activity and make it difficult to return to work (Hnizdo et al., Citation2000). Those who are infected with TB more than once – common in occupations such as mining – are even more likely to experience long-term, chronic lung problems after recovery (Hnizdo et al., Citation2000). Thus, TB can deplete human capital in the short and long-term, heightening the importance of transmission prevention, early diagnosis, and timely treatment.

Workplace stigma

Tuberculosis is a highly stigmatised disease in India (Mukerji & Turan, Citation2018). Some employers choose to terminate or refrain from hiring PWTB, those with history of TB, and even household members of PWTB (Sabin et al., Citation2021). This stigma is enacted not only by employers, but also by colleagues. In a 2021 study in Puducherry, a worker described being mocked by his coworkers when they saw a specimen container that he was taking to a medical appointment that day (Sabin et al., Citation2021). In the same study, 59.6% of the 47 PWTB described hiding their disease status, many to avoid similar embarrassments (Sabin et al., Citation2021). A survey of factory workers in Myanmar found that 32.9% agreed or strongly agreed that a worker with TB should be dismissed from their job, and 49.9% disagreed or strongly disagreed with working closely with a colleague who had been diagnosed with TB (Thu et al., Citation2012). Perceived stigma drives individuals to hide their diagnosis, delay diagnosis and treatment, and disengage from treatment. Such behaviour can lead to TB transmission in the workplace.

The risk of TB transmission in the workplace is particularly high in jobs in which workers work in close proximity to each other in poorly ventilated spaces, such as mines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citationn.d.). Further, some occupations (e.g. miners) have workers live in dormitories or worker camps, where multiple people may sleep in the same room and workers remain in close contact during meals and leisure time. Dormitory living is associated with increased risk of spread of numerous respiratory diseases (Gorny et al., Citation2021). Workers in other fields with similar living conditions, such as construction and agricultural workers, may also be at increased risk of TB exposure from coworkers (Igari et al., Citation2009; Li et al., Citation2011).

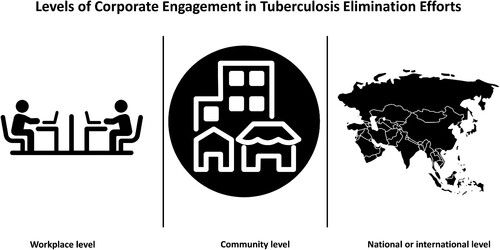

Current models of corporate engagement in TB elimination

The immense scale of the TB pandemic, a lack of awareness and knowledge, and focus on other objectives can make it daunting for businesses to get involved in elimination efforts. However, interested corporate partners have been able to engage and have a meaningful impact in a variety of ways, which we have divided into three main levels: the workplace level, where they focus on employee health only; the community level, where they tackle TB in the communities they inhabit; and the national or international level ().

Figure 2. Businesses can engage in TB elimination efforts at three different levels based on their ability and resources.

Workplace level

The employee level of corporate involvement focuses on corporations providing screening and care to their own workers.

One notable example of corporate engagement at the employee level is the Brihanmumbai Electricity Supply and Transport (BEST) in Mumbai, which has over 40,000 employees and serves over 3.5 million commuters daily (May the BEST Win - BEST, Mumbai, Citationn.d.). BEST provides free TB treatment both in-house and at TB clinics, and has a three-tier follow-up system wherein workers with TB are contacted not only by government healthcare workers, but also by medical officers at the depot dispensary and finally by company pulmonologists (BEST in India Experiences Benefits of a Comprehensive Response to TB and HIV, Citation2018). BEST also provides paid leave for up to one year for employees with TB (BEST in India Experiences Benefits of a Comprehensive Response to TB and HIV, Citation2018). This approach has led to 100% treatment adherence and a 90% reduction in mortality among BEST workers since the initiation of the programme (BEST in India Experiences Benefits of a Comprehensive Response to TB and HIV, Citation2018). The company has also benefited: absenteeism due to TB dropped from an average of over 12 months in 2012 to 6-8 months by 2018 (BEST in India Experiences Benefits of a Comprehensive Response to TB and HIV, Citation2018).

Full-time workers are likely to spend most of their working hours at their workplace, and in certain industries, workers may also live at their place of work, making workplaces a logical site for active surveillance. This is particularly true for migrant workers who do not have fixed residences and who can fall through the cracks of the public health system. In response, an initiative entitled System for Workplace Engagement to Eliminate TB (SWEET) was pioneered in Kozikhode, India in November 2021 to provide HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease screening and awareness events at workplaces with migrant workers (“Pilot Project Launched in Kozhikode to Detect Tuberculosis among Workers,”, Citation2021). Results are forthcoming, but other active surveillance programmes have seen successful outcomes. In a 2006 study of screenings for pulmonary TB among workers at an industrial park in Taiwan, researchers found a nearly threefold-higher yield of new cases compared with the national surveillance programme, demonstrating a potential benefit of active case-finding in a workplace setting (Su et al., Citation2006). Given that these results occurred in a high-income, low prevalence country, active case-finding in countries with higher prevalence of TB disease may see even more striking results.

Similarly, Sibanye-Stillwater, a leading South African mining company, has prioritised TB care for its employees (Home Sibanye-Stillwater, Citationn.d.). In South Africa, miners have a TB rate estimated at 2,500-3,000 cases per 100,000 individuals, three times that of the general population (The World Bank, Citationn.d.). Sibanye-Stillwater has therefore implemented several strategies to provide TB diagnostic services and treatment support for its employees, such as making TB screenings and treatment available at primary health centres within walking distance of worksites (Sibanye-Stillwater, Citation2021). Between 2014, when the corporation began its efforts to eliminate TB among its gold miners, and 2020, active TB cases were reduced from 832 to 257, with a total prevalence of 6.654 active cases per every thousand employees (Sibanye-Stillwater, Citation2021).

Workplaces with high TB risks may have to adopt different measures than those without particularly elevated risks. In high-risk workplaces, such as those where employees work in confined areas, offering regular TB screening at the workplace and providing paid sick leave and health insurance are important, as exemplified by Sibanye-Stillwater. In low-risk workplaces, at a minimum employers should implement awareness and destigmatizing campaigns along with instituting rapid referral for symptomatic individuals.

Community level

In addition to actions directly benefiting their own employees, corporate entities can focus on programmes at the community level, such as within their city or district. Nayara Energy is an Indian fuel retail network that operates the second-largest refinery in the country (Nayara Energy Homepage, Citation2022). The corporation has undertaken a number of actions to improve outcomes for PWTB in local communities, among other healthcare and development programmes (Nayara Energy Limited, Citationn.d.). Through Project Tushti, the company provides nutritional support to TB patients (Nayara Energy Limited, Citationn.d.). Undernutrition is associated with increased risk of progression from latent to active TB, and worse treatment outcomes for persons with active TB, so improving nutrition can reduce TB incidence and mortality (Carwile et al., Citation2022). The company has also funded mobile health vans to increase healthcare access in remote communities, and organised health camps and mobile health applications (Nayara Energy Continues to Improve Access to Healthcare in Villages Surrounding Its Vadinar Refinery, Citation2020).

Another instance of a corporation engaging at the community level is Medanta, a group of specialty hospitals in India (Medanta, Citation2022) that has developed Mission TB Free Haryana as part of its social outreach (Medanta, Citation2019). The corporation supplies vans equipped with X-ray machines to provide free TB screening to persons living in the Indian state of Haryana (Medanta, Citation2019). In a study examining 121 smear-negative, presumptive TB patients who received screenings by Medanta, 39 had X-rays indicative of TB, with a cost of $32 for each smear-negative TB case detected (Datta et al., Citation2019). Medanta is now scaling up this intervention in four additional Indian states (Medanta, Citation2019).

Community level activities also have considerable reputational benefits for businesses (Kline, Citationn.d.) and help them integrate themselves into the communities in which they operate. In the long term, creating a healthier community can also benefit businesses by providing a healthier workforce and a healthier consumer base to purchase their goods and services (Gutiérrez & Jones, Citation2004; Hohnen & Potts, Citation2007).

National/international level

Corporate entities can also focus on social and health interventions at a national or even international level. Since 2004, India’s branch of GSK, a healthcare company, has partnered with TB Alliance to develop new low-cost pharmaceuticals to treat TB and make therapy accessible to impoverished Indians (TB Alliance and GSK Announce Partnership to Develop New TB Therapeutics, Citation2021). These initiatives are done as corporate-social responsibility initiatives in addition to the company’s regular, for-profit business in the healthcare industry.

Similarly, Beckton-Dickinson (BD) is a medical technology company that manufactures medical devices, instruments, and reagents (Advancing the World of Health BD, Citationn.d.). The company has developed a TB diagnostic system that uses liquid culture to provide TB results much faster than a traditional culture test and has formed partnerships to provide accessible pricing in high-need, low-resource settings (Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance: Tuberculosis, Citation2022).

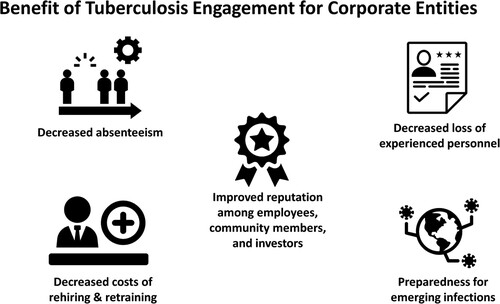

Benefits of engaging in TB programmes

Businesses stand to gain in numerous ways from engaging with TB elimination efforts (). Investing in TB programmes could bring rich dividends to businesses through improved economic productivity and reputational gains. Besides, investments in TB are likely to be very efficient with a high return on investment. Indeed, TB control interventions in India have been found to generate a return of US$115 for every $1 invested (Goodchild et al., Citation2011).

Direct economic benefits

Promoting TB screening and care in the workplace may benefit PWTB, their households, their employers, and the healthcare system. Access to TB screening at the workplace reduces the need for workers to travel to medical facilities, shortening costly diagnostic journeys and reducing absenteeism (HOME Ending Workplace TB, Citation2022). Screening of all employees can identify those with latent TB or recent TB exposures whose risk of TB disease could be reduced through a short course of TB preventive therapy (Fox et al., Citation2017). Screening may also catch those with subclinical TB disease, who are infectious despite being asymptomatic, thereby reducing the risk of transmission in the workplace (Pai et al., Citation2016). Early diagnosis may also prevent long-term disability associated with TB disease (Hnizdo et al., Citation2000; Kranzer et al., Citation2013).

Workplace screenings can have direct financial benefits for corporate entities. AngloGold, a South African mining company, has estimated that each TB case costs $410 in lost productivity. Despite annual screening costs of $90/employee, these TB screenings were found to be cost-effective, particularly among HIV-positive employees, with an estimated savings of $105 for every HIV-positive employee screened (Maher et al., Citation2003).

Preparedness for management of emerging infectious threats

In addition to TB-related benefits, businesses with workplace TB programmes may be more agile and suffer less disruption of their economic activities in the setting of new emergent infectious diseases. For instance, Sibanye-Stillwater’s annual report recognised that their previous experience with TB meant that they had well-trained medical staff and adequately equipped facilities to adapt to COVID-19, another airborne disease (Sibanye-Stillwater, Citation2021). In fact, the company’s capacity exceeded that of the national health service and Sibanye-Stillwater was able to offer COVID-19 vaccinations to both their mineworkers and community members (Njini, Citation2021).

Increased demand for social responsibility by investors

Corporate investors are increasingly conscious of the socio-cultural footprint of their companies, so companies that embrace and publicise social initiatives may be more likely to attract investors. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing has become increasingly popular in recent years, wherein investors assess the moral values of their investments as well as the expected risk and return (Hayat & Orsagh, Citation2015). Increasingly, investors aim to align their moral beliefs with their investments (Giese et al., Citation2019). Conversely, people are less willing to invest in organisations or geographic regions that do not share their values. For instance, due to pressure from both investors and consumers, hundreds of companies have suspended operations in Russia or ended business partnerships due to the country’s invasion of Ukraine (“Companies Are Getting Out of Russia, Sometimes at a Cost,”, Citation2022). The rise of ESG investing incentivizes businesses to make TB elimination part of their mission.

Strategies for encouraging business engagement with TB

Given the enormous potential from corporate engagement in TB elimination, we polled the symposium audience regarding the best ways to convince businesses to address India’s TB epidemic. Their responses are included in .

In addition to undertaking initiatives on their own, corporate entities can form partnerships with NGOs, governmental agencies, and other corporations. The Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, in collaboration with USAID, has developed the Corporate TB Pledge in conjunction with the Indian government, which has the ambitious goal of eliminating TB by 2025 (Corporate TB Pledge Home, Citation2022). In signing the pledge, businesses agree to use their resources to raise awareness about TB and improve TB health outcomes (Corporate TB Pledge Home, Citation2022). Signatories to the corporate TB pledge are engaged in a wide range of activities ranging from workplace interventions to procurement of drugs to treat drug-resistant TB (India TB Report: Coming Together to End TB Altogether, Citation2022). Depending on their level of commitment, the more than 150 business partners are assigned to one of four levels ranging from silver to diamond, a classification system that also has reputational benefits for the companies. Similarly, Ending Workplace TB (EWTB) is a collaborative partnership between private sector leaders (e.g. Johnson & Johnson) and technical agencies (e.g. the Global Fund), with the primary focus of supporting companies to improve their own workplace health offerings and making sure that workers are protected, as much as possible, from the spread of TB in the workplace (HOME Ending Workplace TB, Citation2022). Corporate partners can also fund governmental initiatives, such as the Tata Trust’s provision of a grant to the India TB Research Consortium to support diagnostic and preventive work (Overview: Addressing India’s TB Challenge through Research, Innovation and Partnership, Citation2017). The Indian government has also recently launched the Nikshay Mitra programme, which allows corporate partners and other entities to ‘adopt’ neighbourhoods or individual TB patients and cover the cost of their treatment or a nutritional intervention (Boda, Citation2022; “Now, Adopt a TB Patient, Sponsor Treatment,”, Citation2022). The Indian government has also developed a guidance document for including the private sector in efforts to eliminate TB (Guidance Document on Partnerships: Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme, Citation2019). This helpful document can be used as a guide for corporations who are interested in working with the National TB Elimination Programme.

Corporations may require incentives to promote TB prevention and treatment efforts. One approach is for the government to mandate that a small portion of profits are directed towards socially responsible programmes, as is already the case in India (Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in India, Citation2016). To ensure that India meets its TB elimination goals, the government may need to make a strong and directed call for corporate social responsibility (CSR) investments in TB programmes. Priority areas for corporate social responsibility funds include workplace initiatives, community awareness and screening campaigns, support groups, and nutritional support. There may also be a role for legal requirements for workplace TB programmes in high-risk industries such as mining, pottery, or marble stone and sand extraction, which incur a higher risk of TB disease due to occupational exposures to compounds such as silica dust (Gottesfeld et al., Citation2018). Moreover, government incentives, such as tax breaks, can also promote corporate involvement in TB reduction efforts.

Academics can play a critical role by generating data on the health and economic benefits of corporate TB programmes, which may help convince additional businesses to engage in TB elimination efforts. Further, investigators could conduct implementation research in partnership with businesses to help them optimise and scale up their TB programmes. At present, this remains a fertile field of research in urgent need of attention.

Conclusions

TB is not just a healthcare system concern; it directly affects the bottom lines of private businesses. Businesses are an untapped resource and should be incentivized to invest in TB programmes, whether at a small scale with a focus on workplace protection, a larger scale by furthering TB elimination in their community, or an even larger scale where they seek to become contributors to national or international TB elimination initiatives. In this article, we have presented numerous anecdotal examples of how the corporate sector is contributing to the urgent national TB elimination efforts. However, converting these anecdotal successes into a widespread model will require action from key stakeholders.

The Indian government can find ways to incentivize and possibly even mandate corporate engagement with its TB elimination programme. Academics working on TB-related research and interventions can increase corporate interest in TB elimination by studying the role that businesses can play in reducing TB among their employees and in the community. Governmental and non-governmental organisations like USAID and End Workplace TB can provide guidance to corporate partners on their TB programmes and can incentivize their work through recognition.

Investment in TB programmes is likely to result in rich dividends in both the short and the long term through direct improvements in economic productivity and reputation of the business. More research is needed to determine the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of employer-led TB programmes, although experience with HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment can serve as a guidepost. Such work can help optimally leverage the reach, ingenuity, and resources of Indian businesses to realise the goal of a TB-free India.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- 65% of TB cases in India in 15-45 age group: Health Minister. (2021, August 10). India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/65-percent-tb-cases-india-in-15-45-age-group-health-minister-1838932-2021-08-10.

- Advancing the world of health BD. (n.d.). Retrieved September 4, 2022, from https://www.bd.com/en-us.

- Anand, S. (2022, February 3). India: Retaining talent amid the great resignation. The Society for Human Resource Management, https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/global-hr/pages/india-great-resignation.aspx.

- Arinaminpathy, N., Batra, D., Khaparde, S., Vualnam, T., Maheshwari, N., Sharma, L., Nair, S. A., & Dewan, P. (2016). The number of privately treated tuberculosis cases in India: an estimation from drug sales data. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(11), 1255–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30259-6

- BEST in India experiences benefits of a comprehensive response to TB and HIV. (2018.

- Boda, T. (2022, September 9). Good response to ‘Nikshay Mitra’ programme in Andhra Pradesh. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/andhra-pradesh/good-response-to-nikshay-mitra-programme-in-andhra-pradesh/article65870447.ece.

- Business sector can play key role in the AIDS response in Africa. (2011, April 6). UN AIDS. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2011/april/20110406heineken.

- Carwile, M. E., Hochberg, N. S., & Sinha, P. (2022). Undernutrition is feeding the tuberculosis pandemic: A perspective. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, 27, 100311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jctube.2022.100311

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). TB’s Grip on the Mining Community. Retrieved September 4, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/globalhivtb/who-we-are/features/miningcommunity.html.

- Combating Drug-Resistant TB Through Public–Private Collaboration and Innovative Approaches. (2012). In Facing the Reality of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in India: Challenges and Potential Solutions: Summary of a Joint Workshop by the Institute of Medicine, the Indian National Science Academy, and the Indian Council of Medical Research. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100398/.

- Companies Are Getting Out of Russia, Sometimes at a Cost. (2022, August 25). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/russia-invasion-companies.html.

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in India. (2016). Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry. https://csrcfe.org/about-csr-in-india-public-policy/.

- Corporate TB Pledge Home. (2022). USAID and Swasti Health Catalyst. https://tb.learning4impact.org/corporate-tb-pledge.

- Datta, B., Prakash, A. K., Ford, D., Tanwar, P. K., Goyal, P., Chatterjee, P., Vipin, S., Jaiswal, A., Trehan, N., & Ayyagiri, K. (2019). Comparison of clinical and cost-effectiveness of two strategies using mobile digital x-ray to detect pulmonary tuberculosis in rural India. BMC Public Health, 19(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-019-6421-1

- Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance: Tuberculosis. (2022). Becton Dickinson. https://www.bd.com/en-us/about-bd/esg/tuberculosis.

- Fox, G. J., Dobler, C. C., Marais, B. J., & Denholm, J. T. (2017). Preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis infection—the promise and the challenges. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 56, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.006

- Fuller, J., & Kerr, W. (2022, March 23). The great resignation didn’t start with the pandemic. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/03/the-great-resignation-didnt-start-with-the-pandemic.

- Garba, D. (2017, June 28). This is how India can eliminate TB by 2025. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/06/this-is-how-india-can-beat-tb/.

- Giese, G., Lee, L. E., Melas, D., Nagy, Z., & Nishikawa, L. (2019). Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. Journal of Portfolio Management, 45(5), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2019.45.5.069

- Goodchild, M., Sahu, S., Wares, F., Dewan, P., Shukla, R., Chauhan, L., & Floyd, K. (2011). A cost-benefit analysis of scaling up tuberculosis control in India. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 15(3), 358–362. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21333103/.

- Gorny, A. W., Bagdasarian, N., Koh, A. H. K., Lim, Y. C., Ong, J. S. M., Ng, B. S. W., Hooi, B., Tam, W. J., Kagda, F. H., Chua, G. S. W., Yong, M., Teoh, H. L., Cook, A. R., Sethi, S., Young, D. Y., Loh, T., Lim, A. Y. T., Aw, A. K. L., Mak, K. S. W., & Fisher, D. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 in migrant worker dormitories: Geospatial epidemiology supporting outbreak management. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 103, 389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.148

- Gottesfeld, P., Reid, M., & Goosby, E. (2018). Preventing tuberculosis among high-risk workers. The Lancet Global Health, 6(12), e1274–e1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30313-9

- Guidance Document on Partnerships: Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. (2019).

- Gutiérrez, R., & Jones, A. (2004). Corporate social responsibility in Latin America: An overview of Its characteristics and effects on local communities. In M. Cotreras (Ed.), Corporate social responsibility in Asia and Latin America (pp. 151–187). Inter-American Development Bank.

- Hayat, U., & Orsagh, M. (2015). Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues in Investing. https://doi.org/10.2469/CCB.V2015.N11.1.

- Hnizdo, E., Singh, T., & Churchyard, G. (2000). Chronic pulmonary function impairment caused by initial and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis following treatment. Thorax, 55(1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.55.1.32

- Hohnen, P., & Potts, J. (2007). Corporate Social Responsibility: An Implementation Guide for Business. http://www.iisd.org.

- HOME Ending Workplace TB. (2022). Ending Workplace TB. https://www.ewtb.org/.

- Home Sibanye-Stillwater. (n.d.). Retrieved September 4, 2022, from https://www.sibanyestillwater.com/.

- Igari, H., Maebara, A., Suzuki, K., & Shimura, A. (2009). Tuberculosis among construction workers in dormitory housing in Chiba City. Kekkaku : [tuberculosis], 84(11), 701–707. https://europepmc.org/article/med/19999591.

- India TB Report 2022: Coming Together to End TB Altogether. (2022). https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/IndiaTBReport2022/TBAnnaulReport2022.pdf.

- Kline, M. (n.d.). Csr Can make your reputation shine. Inc. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.inc.com/maureen-kline/how-to-manage-your-companys-reputation.html.

- Kranzer, K., Afnan-Holmes, H., Tomlin, K., Golub, J. E., Shapiro, A. E., Schaap, A., Corbett, E. L., Lönnroth, K., & Glynn, J. R. (2013). The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active tuberculosis disease: a systematic review [State of the art series. Case finding/screening. Number 2 in the series]. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 17(4), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.12.0743

- Li, T., He, X.-X., Chang, Z.-R., Ren, Y.-H., Zhou, J.-Y., Ju, L.-R., & Jia, Z.-W. (2011). Impact of new migrant populations on the spatial distribution of … : Ingenta Connect. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 15(2), 163–168. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2011/00000015/00000002/art00005.

- Maher, D., Boldrini, F., Pathania, V., Alli, B. O., Gabriel, P., Kisting, S., & Norval, P.-Y. (2003). Guidelines for workplace TB control activities: The contribution of workplace TB control activities to TB control in the community.

- May the BEST Win - BEST, Mumbai. (n.d.). Corporate TB Pledge. Retrieved September 4, 2022, from https://www.corporatetbpledge.org/best-mumabi-impact-story/.

- Medanta. (2019, November 19). Medanta’s Mission TB Free India. https://www.medanta.org/patient-education-blog/mission-tb-free-haryana/.

- Medanta. (2022). Medanta. https://www.medanta.org/.

- Mukerji, R., & Turan, J. M. (2018). Exploring manifestations of TB-related stigma experienced by women in Kolkata, India. Annals of Global Health, 84(4), 727. https://doi.org/10.29024/aogh.2383

- Muniyandi, M., Ramachandran, R., & Balasubramanian, R. (2005). Costs to patients with tuberculosis treated under DOTS program. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis, 52, 188–196.

- National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis: 2017-25 - Elimination by 2025. (2017). https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/National%20Strategic%20Plan%202017-25.pdf.

- Nayara Energy Continues to Improve Access to Healthcare in Villages surrounding its Vadinar Refinery. (2020). www.nayaraenergy.com.

- Nayara Energy Homepage. (2022). Nayara Energy. https://www.nayaraenergy.com/.

- Nayara Energy Limited. (n.d.). CSR Annual Action Plan for FY 2021-22.

- Njini, F. (2021, January 15). Sibanye: SA miners can scale up vaccination by inoculating workers and communities. Fin24 / Bloomberg News. https://www.news24.com/fin24/companies/mining/sibanye-sa-miners-can-scale-up-vaccination-by-inoculating-workers-and-communities-20210115.

- Now, adopt a TB patient, sponsor treatment. (2022, September 17). The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/karnataka/2022/sep/17/now-adopt-a-tb-patient-sponsor-treatment-2499125.html.

- Overview: Addressing India’s TB Challenge through Research, Innovation and Partnership. (2017). India TB Research Consortium. https://itrc.icmr.org.in/our-work/thematic-areas/overview.

- Pai, M., Behr, M. A., Dowdy, D., Dheda, K., Divangahi, M., Boehme, C. C., Ginsberg, A., Swaminathan, S., Spigelman, M., Getahun, H., Menzies, D., & Raviglione, M. (2016). Tuberculosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(16076), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.76

- Pai, M., Bhaumik, S., & Bhuyan, S. S. (2017). India’s plan to eliminate tuberculosis by 2025: converting rhetoric into reality. BMJ Global Health, 3(2), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000783

- Pantoja, A., Floyd, K., Unnikrishnan, K., Jitendra, R., Padma, M., Lal, S., Uplekar, M., Chauhan, L., Kumar, P., Sahu, S., Wares, F., & Lonnroth, K. (2009). Economic evaluation of public-private mix for tuberculosis care and control, India. Part I. Socio-economic profile and costs among tuberculosis patients. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 13(6), 698–704. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2009/00000013/00000006/art00004#.

- Petkoski, D., & Kersemaekers, S. (2003). The Role of Businesses in Fighting HIV/AIDS. www.csrwbi.org.

- Pilot project launched in Kozhikode to detect tuberculosis among workers. (2021, November 2). The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/kozhikode/pilot-project-launched-in-kozhikode-to-detect-tuberculosis-among-workers/article37306229.ece.

- Ray, T., Sharma, N., Singh, M., & Ingle, G. (2005). Economic burden of tuberculosis in patients attending DOT centres in Delhi. Journal of Communicable Diseases, 37(2), 93–98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16749271/.

- Sabin, L. L., Thulasingam, M., Carwile, M., Babu, S. P., Knudsen, S., Dong, L., Stephens, J., Fernandes, P., Cintron, C., Horsburgh, C. R., Salgame, P., Ellner, J. J., Sarkar, S., & Hochberg, N. S. (2021). “People listen more to what actors say”: A qualitative study of tuberculosis-related knowledge, behaviours, stigma, and potential interventions in Puducherry, India. Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1990372.

- Sibanye-Stillwater. (2021). Integrated Report 2020. www.sibanyestillwater.com.

- Sinha, P., Carwile, M., Bhargava, A., Cintron, C., Acuna-Villaorduna, C., Lakshminarayan, S., Liu, A. F., Kulatilaka, N., Locks, L., & Hochberg, N. S. (2020). How much do Indians pay for tuberculosis treatment? A cost analysis. Public Health in Action, 10(3), 110. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.20.0017

- Su, S.-B., Chang, C.-T., Chen, K.-T., & Guo, H.-R. (2006). Screening for pulmonary tuberculosis using chest radiography in new employees in an industrial park in taiwn. Epidemiology, 17(6), S186. https://journals.lww.com/epidem/Fulltext/2006/11001/Screening_for_Pulmonary_Tuberculosis_Using_Chest.470.aspx.

- TB Alliance and GSK announce partnership to develop new TB therapeutics. (2021, March 18). TB Alliance. https://www.tballiance.org/news/tb-alliance-and-gsk-announce-partnership-develop-new-tb-therapeutics.

- Thu, A., Ohnmar, Win, H., Nyunt, M. T., & Lwin, T. (2012). Knowledge, attitudes and practice concerning tuberculosis in a growing industrialised area in Myanmar. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 16(3), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.10.0754

- Veesa, K. S., John, K. R., Moonan, P. K., Kaliappan, S. P., Manjunath, K., Sagili, K. D., Ravichandra, C., Menon, P. A., Dolla, C., Luke, N., Munshi, K., George, K., & Minz, S. (2018). Diagnostic pathways and direct medical costs incurred by new adult pulmonary tuberculosis patients prior to anti-tuberculosis treatment – Tamil Nadu, India. PLOS ONE, 13(2), e0191591. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0191591

- The World Bank. (n.d.). The Southern Africa TB in the Mining Sector Initiative. Retrieved September 4, 2022, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/the-southern-africa-tb-in-the-mining-sector-initiative.

- World Health Organization. (2021a). Global Tuberculosis Report 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/digital/global-tuberculosis-report-2021.

- World Health Organization. (2021b, October 14). Tuberculosis. WHO Fact Sheets. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis.