ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the perception of patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) of the accreditation programme to improve their capacity to provide family planning (FP) services in Lagos and Kaduna, Nigeria. A cross-sectional mixed-method approach among 224 PPMVs was used to investigate their perception, willingness to pay for and adhere to the programme, its benefits, and the community women’s perception of the value of PPMVs. Chi-square analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM) were used to analyse survey data, while focus group discussions (FGDs) were analysed using the grounded theory. PPMVs were enthusiastic because of the benefits, including increased clientele, revenue, and improved service provision capacity. Approximately 97% of PPMVs found the programme acceptable and were willing to pay, with 56% and 71% willing to pay between N5000-N14900 ($12–36) and N25000-N35000 ($60–87), respectively. A significant relationship between educational attainment, location, and willingness to pay was revealed. Among community women, the fear of side effects, lack of partners’ support, myths and misconceptions, and lack of access to modern contraceptives were factors affecting contraceptive uptake. The capacity of PPMVs to improve FP uptake is promising and can be leveraged to improve health outcomes in communities while strengthening their businesses.

Introduction

Background

With over 170 million people, Nigeria is the most populous nation and one of the largest economies in Africa (Iheoma et al., Citation2016). However, over 50% of its population lives below the poverty line, with poor access to medicines for minor disorders and symptoms (Asakitikpi & Asakitikpi, Citation2019; Iheoma et al., Citation2016). Patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) are drugstores or sales representatives who sell trademarked non-prescription over-the-counter drugs (OTC) for profit (Breslin & McKeown, Citation2022; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020; Pharmacists Council of Nigeria, Citation2020). These medicine stores are central in providing essential medicines and increasing access to healthcare services for lower-income communities (Brieger et al., Citation2004; Iheoma et al., Citation2016).

PPMVs are often small commercial drugstores within the suburban areas of the country, providing the first line of healthcare to the population. Studies have shown that they are highly accessible, affordable, and valuable sources of health care services, products, and information (Beyeler et al., Citation2015; Brieger et al., Citation2004; Iheoma et al., Citation2016). National surveys show that PPMVs are usually the first source of care for between 8% and 63.5% of illnesses in the population. For children under 5 years, PPMVs are the first point of care in up to 62.5% of fever-related cases (Beyeler et al., Citation2015; National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2013; Nigerian Population Commission, Citation2009; Citation2012; NPC/ICF, Citation2018). They also provide services for up to 60% of adults seeking various treatments (Okeke et al., Citation2006; Onwujekwe et al., Citation2011; Onwujekwe et al., Citation2011; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020). However, studies show a wide variation in the utilisation of PPMVs for children and adults with different health conditions which differs across geographical locations for similar conditions (Berendes et al., Citation2012; Beyeler et al., Citation2015; Fajola et al., Citation2011; Okeke & Okeibunor, Citation2010; Onwujekwe et al., Citation2011; Prach et al., Citation2015; Treleaven et al., Citation2015; Uguru et al., Citation2009).

Despite the low educational qualification of PPMVs (Berendes et al., Citation2012; Beyeler et al., Citation2015; Brieger et al., Citation2004; Iheoma et al., Citation2016; Okeke et al., Citation2006), they remain the most reliable sources of healthcare for the most vulnerable populations (Iheoma et al., Citation2016; Livinus et al., Citation2010); thus, they must be considered as important stakeholders among Nigerian healthcare providers as approximately 33% of Nigerians access healthcare services from PPMVs (Beyeler et al., Citation2015; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020). However, there is a general opinion among other stakeholders that PPMVs’ capacity to provide good quality services are limited, and this is associated with their level of formal health training and business management skill (Corroon et al., Citation2016; OlaOlorun et al., Citation2022; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020).

Poor quality of service by PPMVs amidst the growing demand for their services remains a source of concern for public health investors (Berendes et al., Citation2012; Brieger et al., Citation2004; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020). However, despite their poor educational background, with adequate training and access to value-adding business incentives, PPMVs can gain sufficient knowledge and the right motivation to provide quality healthcare services (Livinus et al., Citation2010). Besides improving the quality of service, there is a need to prove the value for investment to justify the capital-intensive interventions for PPMVs, such as training programmes, accreditation, and purchase of quality drugs (Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020; Onwujekwe et al., Citation2011; Prach et al., Citation2015; OlaOlorun et al., Citation2022). Understanding the cost–benefit of a business is one way to evaluate the investment in the programme (Belfield & Levin, Citation2010; Haveman & Weimer, Citation2001; Kee, Citation2004).

The Pharmacy Council of Nigeria (PCN) is a Federal Government parastatal established by the Act in 2004 to regulate and control pharmacy education, training, and practice (Pharmacy Council of Nigeria, Citation2022). Moreover, it regulates the PPMV practice in the country. The IntegratE project, co-funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) for Mothers, provides a learning opportunity for PPMVs in Nigeria to improve the quantity and quality of healthcare services they provide. The Society for Family Health (SFH), with support from the Federal Ministry of Health and the PCN, is leading a consortium of partners implementing the IntegratE project, which seeks to pilot a three-tier accreditation system for PPMVs across Lagos, Kaduna, Kano, Gombe, Nasarawa, Niger, Sokoto, and Borno states to increase the capabilities of these providers to offer quality services, comply with accreditation regulations, and report service data to the National Health Information Management System (NHIMS). It is essential to ensure that PPMVs obtain value for their investment in the accreditation system to sustain their participation in the programme.

Rationale

The three-tier accreditation process focuses on improving the capacity of PPMVs that are part of Nigeria’s informal private sector to provide family planning commodities and services and improve the uptake of contraceptives at the community level. Training and accreditation needs are high, given that owners of a significant proportion of PPMVs in Nigeria do not have the requisite health qualifications (Corroon et al., Citation2016; OlaOlorun et al., Citation2022; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020).

PPMVs are private profit-oriented businesses and often the first line of contact for health services at the community level because of their accessibility and lower costs (Brieger et al., Citation2004; Iheoma et al., Citation2016; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020). However, there has not been an assessment to determine their willingness to pay for or participate in intervention programmes which they are a part of. This also underscores the need to understand factors influencing their businesses, specifically, the provision of FP services and the value proposition of the accreditation programme and their willingness to pay for and adhere to it.

To provide evidence for the discussion on a change in health-related intervention budgets, there is a need to determine the return on investment (ROI) and opportunity cost for the intervention carried out at any level (local and/or national) (Abubakar et al., Citation2022; Masters et al., Citation2017). The study notes that ROI and opportunity cost require the availability of appropriately structured financial records. Measuring ROI in terms of perceived benefits from the investments is necessary, as PPMVs rarely keep structured financial ledgers of their businesses. This study investigated the perceived (monetary and non-monetary) benefits and usefulness of the accreditation programme for PPMVs, and their willingness to pay for and adhere to it to ensure sustainability beyond donor funding.

Objective

The study evaluated the accreditation programme for PPMVs by examining their perceived benefits and willingness to pay for it, as well as understanding the perceptions of PPMVs and community women towards the family planning services.

Conceptual framework

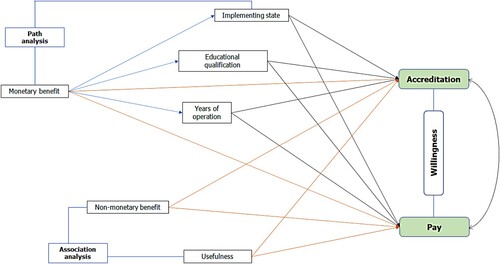

Based on theoretical postulations and empirical evidence (Brieger et al., Citation2004; Corroon et al., Citation2016; Iheoma et al., Citation2016; OlaOlorun et al., Citation2022; Onwujekwe et al., Citation2011; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020; Prach et al., Citation2015), this research conceptualized that PPMVs were interested in programmes that would improve their service delivery and societal perception of the services. However, certain factors might influence their willingness to continue participation in and pay for the PCN tier accreditation programme. The study framework assumed that the perceived monetary and non-monetary benefits and programme usefulness were independent variables, which were directly related to the two study outcomes (willingness to accept the accreditation programme and pay for it). The intervening variables (modifiers) that were hypothesised as capable of influencing the relationships between the dependent and independent variables were: implementation site (defined as the area of programme implementation), educational background (PPMVs with or without health qualification), and years of operation (the duration of service provision).

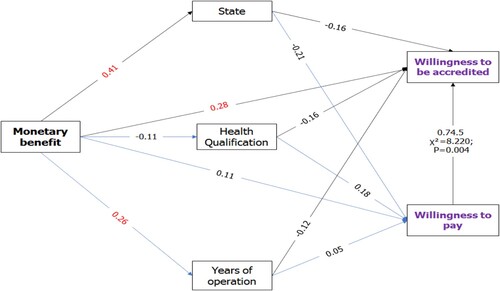

We built the conceptual framework to evaluate the association between indicators of usefulness and non-monetary benefit and the willingness to continue the accreditation and pay for the accreditation, and using the direct and indirect effect path model of the relationship between monetary benefit and the willingness to continue on and pay for the accreditation ().

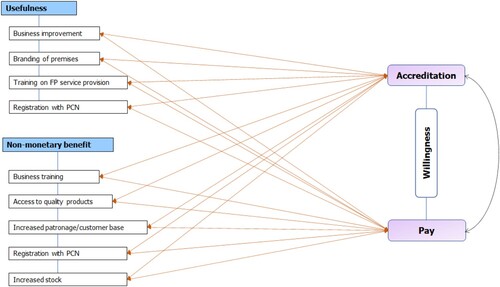

Chi-square association model: programme usefulness and non-monetary benefits

The study examined the association between the indicators for usefulness and non-monetary benefit of the programme to the PPMVs, and their willingness to continue accrediting their business and pay for the accreditation (). The following are the indicators to evaluate the association between usefulness and non-monetary benefits and willingness to (1) continue with the accreditation and (2) pay for it.

Perceived usefulness of the accreditation

Branding

Training on FP services

Access to quality contraceptives

Business training

Perceived non-monetary benefits

Licensing/registration

Access to quality products

Increased patronage

Recognition by the National Association of Patent and Proprietary Medicines (NAPPMED)/PCN

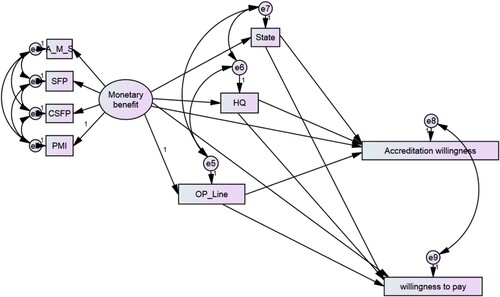

Path model: monetary benefit from programme participation

The direct and indirect effect of the perceived monetary benefit of the programme and their willingness to continue accrediting their business and pay for the accreditation (). The following are the variables included in the path model and their indicators.

Exogenous (independent) variables – monetary benefits with the following indicators:

Revenue increase

Average monthly sales in 2021

Sales from FP services

Percentage increase in sales in 2021

Influencer variables (moderators) –

e. Implementation state (Lagos/Kaduna)

f. Health qualification (yes/no)

g. Years of operation (<5/5 −10/>10 years)

Endogenous (dependent) variables –

h. Willingness to continue with the accreditation

i. Willingness to pay for it

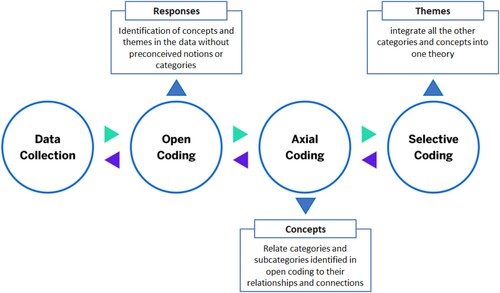

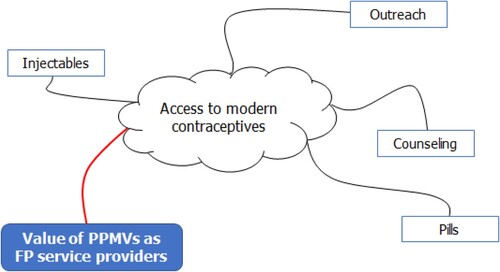

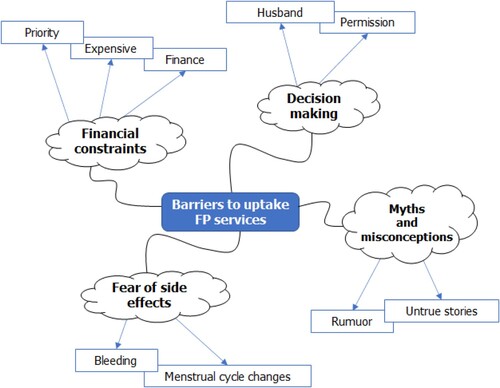

Grounded theory: community perception of PPMVs services

The grounded theory was used to arrive at the core theme (Noble & Mitchell, Citation2016) the PPMVs accredited programme – the value of PPMVs as family planning service provider and barriers to uptake of family planning service ().

Materials and methods

Study design

The study used an analytical cross-sectional design involving quantitative and qualitative approaches to gather data about PPMVs’ perception of the accreditation programme, willingness to pay for it, adhere to it, and its impact on their businesses. The study utilised semi-structured questionnaires and FGDs conducted amongst the PPMVs.

Study context and intervention description

MSD for Mothers and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded Phase I of IntegratE, a four-year project (2017–2021) to expand access to a range of quality family planning (FP) and primary health care (PHC) services by engaging local private drug shops (PPMVs). With support from the Federal Ministry of Health, the SFH led a consortium of partners that implemented the first phase of the programme in collaboration with the PCN. The programme targeted 1,200 PPMVs across Lagos and Kaduna to increase their capacity to offer quality services (primarily FP and basic PHC services), comply with state accreditation regulations, and report service data to the NHIMS.

PPMVs were categorised into three tiers based on the owners’ qualifications, and tier-specific training modules on FP service provision were developed and deployed. Tier 1 training module focuses on FP counselling and the provision of OTC FP products, including contraceptive pills, cycle beads, and condoms. Tier 2 and Tier 3 training modules focus on the administration of injectables as well as the insertion and removal of implants. Phase II of the project aimed to scale this up to additional states: Kano, Nasarawa, Gombe, and Borno. Training modules were offered at no cost to the PPMVs throughout the project. This study seeks to provide insights into PPMVs’ acceptance of the project and their willingness to bear some costs of the accreditation programme.

Study setting

This was a cross-sectional survey of PPMVs enrolled for Phase I of the project. The study used quantitative and qualitative approaches to obtain information on the perception of the PCN accreditation programme, their willingness to pay for and adhere to the accreditation, and the perceived impact of the accreditation on their businesses. Study participants were the patent medicine store owners who were part of the IntegratE project. Interviews were conducted using semi-structured questionnaires across two states. PPMVs were purposively drawn from the list of PPMVs who were part of the IntegratE project across LGAs in the two states.

Study population

The study population included PPMVs enrolled in Phase I of the project, and community women within the service areas in Lagos and Kaduna, Nigeria. According to the 2021 IntegratE report, the accreditation programme has a total of 7919 (Lagos; 3457 and Kaduna; 4462) registered PPMVs. The distributed according to the state and accreditation category are as follows: Lagos (Tier 1; 3089, Tier 2; 331, and Tier 3; 37) and Kaduna (Tier 1; 2451, Tier 2; 2004, and Tier 3; 7). Between July 2018 and June 2021, 461 CPs and 998 PPMVs enrolled in the IntegratE project were trained in family planning (FP) based on tiering system (IntegratE, Citation2021).

The study selected ten (10) Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Kaduna comprising four (4) urban LGAs (Kaduna North, Kaduna South, Sabon Gari, and Zaria) and six (6) rural LGAs (Igabi, Ikara, Kudan, Makarfi, Rigachikun, and Soba). And six LGAs in Lagos comprising four (4) urban LGAs (Alimosho, Badagry, Ikorodu, and Ojo) and two (2) rural LGAs (Igbogbo bayeku and Epe). Within each LGA, the study ensured an even proportion and distribution of PPMVs. The distribution was to ensure adequate representation of demographic distribution of PPMVs in the study population; as Lagos has more cities, while Kaduna has more villages.

Study sample

The study only included PPMVs who were recruited into the IntegratE project and provided verbal consent to participate in the study. PPMVs who did not meet the above stated criteria were excluded. Additionally, the collected data of PPMVs who withdrew from the accreditation programme did not form part the analysed data.

The Slovin formula (n = N / [1 + Ne2]) was used to determine the sample size from a study population of 998 (IntegratE, Citation2021), at 95% confidence interval, a margin of error of 0.05, and a 10% attrition rate, resulted in a sample size of 313. However, the study was limited by several factors such as availability of resources, access to communities due to security challenges, and the PPMVs and community women’s willingness to participate in the study. Despite these limitations, the study was able to obtain 244 PPMVs (78%) for the survey.

For the FGDs, the study randomly selected two (2) LGAs in each state, one urban and the other rural. In each LGA, the study identified five PPMVs, and five women who live within the vicinity of the PPMVs to participate in the FGD, in which both groups were interviewed differently. By including both urban and rural areas, the study aimed to capture a wide range of experiences and perspectives from PPMVs and community women in both settings. This implied that a total of 16 FGDs were conducted in the study.

Data collection

Thirteen (13) and seven (7) field data collectors administered semi-structured questionnaires to the PPMVs in Kaduna and Lagos, respectively. Each data collector administered an average of 11 questionnaires within the 1-week data collection period (in July, 2022) in the preferred language of the PPMVs. We interviewed participants using a standardised (pre-tested with a reliability of 0.78–0.86) questionnaire administered by trained and experienced research assistants. The questionnaire was prepared in English; however, the interviews were conducted in the PPMVs’ preferred dialect. The PPMVs in Lagos spoke majorly English and/or Yoruba and those in Kaduna, northern Nigeria mostly spoke Hausa and/or English. The FGDs conducted in Kaduna were done in Hausa, while in Lagos, were conducted in English.

Data was captured real time using the Open Data Kit (ODK) electronic system and the process was monitored daily to ensure data quality. The collected variables included participant background characteristics, which were both self-reported and extracted from the project data. The primary outcomes were: willingness to continue with the accreditation programme, pay for it, and adhere to it. The study also obtained information regarding the perceived monetary and non-monetary benefits, and usefulness of the programme to the PPMVs.

The qualitative component of the study comprised FGDs with PPMVs and community women. FGDs were conducted with homogenous groups of PPMVs and community women across the two states, with two FGDs conducted with community women and PPMVs in rural and urban LGAs in each state. The FGDs with the PPMVs provided insights into the factors influencing the provision of FP services by the PPMVs and their participation in the programme, willingness to pay and adhere to the guidelines of the accreditation programme, and the value proposition of the programme to their businesses. Perceptions of community women of the programme, FP service provision, and uptake in their communities were also evaluated.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis

The cleaned data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (IBM® Amos V21.0.0, USA). The study summarised the study demographics and participant characteristics using tables. Chi-square test was used to determine the association between the indicators of usefulness and non-monetary benefits, and willingness to get accredited and pay for the accreditation. Structured equation modelling (SEM) path analysis was used to examine the perceived monetary benefit of the programme and willingness to continue participating in and pay for it (). Path analysis was performed to investigate the initial hypothesis that implementing states, health qualification, location (state), and years of operation significantly influence the willingness of PPMVs to adhere to and pay for the accreditation. SPSS Amos SEM was used to evaluate the relationships in the path model. To account for the non-normal distribution of the model variables, we used the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) as the estimator (Pek et al., Citation2018).

We chose four analyses to assess the fit of the models: (i) The goodness of fit index (GFI) under generalised least squares (GLS) (Tanaka & Huba, Citation1985), (ii) Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, Citation1990), (iii) the Standardised Root Mean Squared Error (SRMR) to test close fit in ordinal factor analysis, and (iv) the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) for an unbiased basis for model rejection using a small sample (Chen et al., Citation2008; Shi et al., Citation2020). Values between 0.90 and 1.0 on Bentler's CFI and value ≥ 0.95 on the GFI indicate that the model provides a good fit to the data (Parry, Citation2020). An SRMR value closer to zero indicates a perfect fit (Shi et al., Citation2020). The study also determined the standardised and unstandardised direct and indirect effects of the exogenous variables on the manifest variable. All analyses were performed with a 95% confidence level, and the significance level (P-value) was set at <0.05.

Thematic analysis

Qualitative interviews were transcribed, and transcriptions were coded into relevant themes and analysed using the grounded theory approach for thematic analyses (Claypoole et al., Citation2017; Creswell, Citation2022; Khan, Citation2014). This involved two research team members forming concepts from the data and independently identify several themes. The researchers agreed upon the themes and coded open-ended comments for each theme. We evaluated each comment using the constant comparative method of the grounded theory (Creswell, Citation2022; Khan, Citation2014).

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration, which provides guidelines for conducting research involving human subjects, which included obtaining informed consent, putting measures in place to ensure confidentiality, and the protection of participants’ rights and welfare. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (NHREC) (approval number NHREC/01/01/2007-29/06/2022).

Results

Of the 224 participating PPMVs, 74 were from Lagos (33%) and 150 from Kaduna (67%). There were more women (130, 58%) than men (94, 42%), and 97 PPMVs (Tier 1) without health qualifications and 127 with health qualifications (Tiers 2 and 3) as described by the Pharmaceutical Council of Nigeria (PCN) 3-Tier Accreditation system (IntegratE, Citation2021). Approximately 26.7% of the PPMVs had been in the business for less than five years. The FP services provided by PPMVs included an array of modern contraceptive options. Condoms and contraceptive pills were the most available options, with 96% and 97% of the PPMVs providing these products on their premises, respectively ().

Table 1. PPMV’s demographic characteristic.

Path model fit

For the path analysis, the fit indices GFI = .988, CFI = 0.998, SRMR = 0.021, and RMSEA = 0.016, and the chi-square goodness of fit (X2 [df = 12] = 12.690, P = 0.392) reflected a model with a very good fit. The perceived ROI associated with FP service provision was significant (), with approximately 9.4% and 90.6% of the PPMVs having average monthly sales of >250,000 naira and between 10,000 and 250,000 naira, respectively. Approximately 17% and 24% of the PPMVs reported that FP service provision improved their revenue to a great and small extent, respectively. Many PPMVs acknowledged that the programme had meaningfully impacted their client flow, with over half of the PPMVs (56%) affirming that FP service provision had a positive impact on their client flow, and over 30% stating that it had a strong positive impact. Approximately 70.1% of PPMVs reported an increase in patronage and customer base, while 54.9% reported that they had access to quality products. Regarding the overall usefulness of the programme to their businesses, 72% of the PPMVs stated that the accreditation programme was very useful to their business. The most significant benefit of the programme was the improvement of their businesses (92%) and training in FP service provision (88.4%), while the least benefit associated with the programme was business training (41.9%) and branding (46.9%).

Table 2. Programme-related outcomes (return on investment).

Programme usefulness, non-monetary benefits, and willingness to be accredited and pay for the programme

As presented in (willingness to get accredited) and (willingness to pay for the accreditation), there was a high acceptability of the programme, with about 97% of the PPMVs willing to continue with the accreditation programme and 92% affirming the programme’s usefulness to their businesses. Business improvement was significantly associated with willingness to obtain accreditation (X2 = 9.436, p = 0.002), but not with willingness to pay for the accreditation (X2 = 1.289, P = 0.256). Access to quality products and increased stock were associated with willingness to pay for the accreditation (X2 = 10.103, P = 0.001), but not with willingness to get accredited (P > 0.05). Branding of premises, training on FP service provision, registration with NAPPMED or PCN, and increased patronage by customers were not associated with the willingness to get accredited or to pay for the accreditation (P > 0.05).

Table 3. The association between indicators of usefulness and non-monetary benefits and the willingness to be accredited.

Table 4. The association between indicators of usefulness and non-monetary benefits and willingness to pay for the accreditation.

Although there was a significant association between PPMVs’ willingness to get accredited and pay for it (X2 = 8.220; P = 0.002), only 74.5% of those willing to be accredited wished to pay (). The differences in the number of PPMVs willing to pay are detailed in . Approximately 56% of the PPMVs were willing to pay between N5000-N14900 ($12–36), which can cover the cost of enrolment and/or licensing with PCN and 14.9% stated that they were willing to pay between N25,000 and N35,000 ($60–87), which can cover the cost of tuition and enrolment in the programme, while 17.9% indicated a willingness to pay above N35,000, which can cover all aspects of the programme (enrolment, tuition, and licensing fees).

Monetary benefit on willingness to adhere to and pay for the accreditation programme

From the path analysis and the resultant coefficients of the model test results in , the perception of monetary benefit was confirmed to have statistically significant direct effects on the willingness to be accredited (β = 0.28, P < 0.05), but not on the willingness to pay for it (P > 0.05). The total effect of monetary benefit on the willingness to pay was (β = 0.02), compared with the willingness to get accredited (β = 0.19). A higher perception of monetary benefit was associated with implementation state of Kaduna (β = 0.41) and longer years of operation (β = 0.26). PPMVs with health qualifications had a lower perception of monetary benefit (β = − 0.11).

Regarding demographic characteristics that influenced the willingness to be accredited and pay for the accreditation (Figure 5), the path analysis showed that in the two states, health qualification and the years of operation had no direct effect on willingness to get accredited. However, state (P = 0.013) and health qualifications (P = 0.024) were significant factors for the willingness to pay for the accreditation. PPMVs from Lagos and those with health qualifications were more willing to pay than those from Kaduna (β = 0.21) and without health qualifications (β = 0.18), respectively. PPMVs operating for a longer time (>10 years) were less willing to be accredited than those with fewer years (<5 years) of operation (β = −0.12). The two implementing states and the health qualification of PPMVs modulated the relationship between perceived monetary benefit and willingness to get accredited and pay for the accreditation. Chi-square analysis showed a 74.5% significant association between willingness to get accredited and pay for the accreditation (χ2 = 8.22, P = 0.004).

PPMVs’ perception of the accreditation programme

The PPMVs stated that they had gained significantly from the project and outlined several benefits, including increased client flow, increased revenue, access to quality drugs, and improved business management skills. They were willing to continue with the accreditation programme because of the benefits they ascribed to it. They also expressed willingness to pay for it if it was affordable.

When ask if they were willing to pay for the accreditation programme;

A PPMV from Kaduna State, stated, ‘yes, I’m willing to pay, but if it’s not much. If it’s too much, it’s going to break our business, we don’t have much capital except if we will get a grant.’

A PPMV from Lagos State, stated, ‘yes, they will be willing to pay depending on the sensitization, because if they are aware of the benefit and what they stand to gain, and if the amount is reasonable … they will be willing to.’

Perceptions of community women

The findings from the interviews with community women were structured in two parts: (i) the value of PPMVs as FP service providers, and (ii) barriers to FP uptake. Word mapping of the themes from the analysis is presented in and .

Value of PPMVs as FP services providers

The word mapping analysis of the FGD showed that the most significant value of the PPMVs to community women were the provision of quality modern contraceptives and FP counselling (Figure 6):

Outreach: Community women could access FP services from PPMVs who conducted routine community outreach for FP planning and other PHC services.

Counselling: Participants in FGDs also stated that PPMVs offered FP counselling services and they could obtain care from them.

Pills: Most of the women stated that the most common modern contraceptives they received from PPMVs were short-acting contraceptive pills.

Injectables: Interviewees who used injectables mentioned that they initially accessed the service from hospitals, but after the accreditation programme, they accessed care from PPMVs.

When ask were they accessed FP services;

A participant from Kaduna State, stated, ‘I did it in the hospital first, but when one PPMV and her team came and did a group sensitisation, I followed them and did it there.’

A participant from Lagos State, stated, ‘I now know how to give myself my contraceptives and don’t miss my shots again because Madam Divine taught me how to self-administer my injectables.’

Barriers to uptake FP services

The word mapping of the theme ‘barriers to uptake FP services’ showed financial constraints, myths and misconceptions, decision-making for FP services and fear of side effects as major barriers ().

Decision-making for FP uptake: Most of the women highlighted that their husbands were the key decision-makers on the use of any form of contraception. A few women stated that they did not require permission from their spouses before using contraceptives.

Myths and misconceptions: Participants stated that rumours/untrue stories from other women, stating that FP could cause permanent infertility, negatively affected their willingness to access FP services.

Fear of side-effects: Bleeding and irregular menstrual cycles were stated as side effects that discouraged the women from using injectables and implants.

Financial constraints: Several participants did not consider FP a high priority compared with other basic healthcare services that they lacked. Some also highlighted that FP services were unaffordable given their other financial commitments.

Discussion

This study illustrates the values derived by PPMVs from the accreditation programme to improve their capacity to provide health services, including FP services at the community level. The PPMVs were enthusiastic about the accreditation programme, cooperated with the government and implementing partners to improve their skills, and included modern contraceptives in the range of services they provided. This finding is consistent with other studies on trained PPMVs across the country, which reported similar trends in acceptability and improved service delivery (Brieger et al., Citation2004; Fajola et al., Citation2011; Livinus et al., Citation2010; Okeke et al., Citation2006; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020; Prach et al., Citation2015).

A combination of individual, social, and systemic factors contributed to Nigeria’s continued low uptake of contraceptives, despite the huge investments. The individual and social factors identified in this study were similar to those identified in other studies conducted in Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries (Randrianasolo et al., Citation2008; Thummalachetty et al., Citation2017). The fear of side effects, lack of support from spouses for FP, myths and misconceptions, and lack of access to modern contraceptives are the factors that should be addressed within communities to facilitate contraceptive uptake (Lee, Citation2021; Sinai et al., Citation2020; Thummalachetty et al., Citation2017). PPMVs, because of their unique placement in the communities they serve as FP service providers, can support to address these issues as well as create awareness and provide counselling for contraceptive use.

As service providers within the informal private sector, PPMVs provide solutions to some imminent problems plaguing Nigeria’s health sector, including the lack of adequate personnel to provide primary health services and the inaccessibility of quality medicines, especially in rural areas (OlaOlorun et al., Citation2022; IntegratE, Citation2021; WHO, Citation2008). Furthermore, the willingness to pay for the accreditation programme and the positive impact of the programme to the PPMVs’ businesses shows the value of institutional support by government, donors, and implementing partners in addressing quality and access issues in the health sector. The provision of incentives to facilitate engagement and payment systems for PPMVs within the programme are additional supports the government, donors, and implementing partners can provide to increase PPMVs’ participation and willingness to pay for this and other health intervention programmes.

The tier levels assigned to the PPMVs within the programme recognise the limitations of the lack of health qualifications for some PPMVs which limit the services they are allowed to provide to their clients. A significant proportion of the PPMVs in this study was assigned tier 1, with no health qualification, thus underscoring the need to ensure the improved capacity necessary to facilitate the provision of quality health services to clients (Berendes et al., Citation2012; Prach et al., Citation2015). This is crucial as they are the closest, more affordable, and most accessible facilities available to healthcare seekers in the communities. Several studies assessing the quality of services provided by PPMVs and the opportunities they provide to make primary healthcare more accessible, stress the value of improving their capacity and enabling them to serve their communities appropriately in light of the problems plaguing the Nigerian health sector (Iheoma et al., Citation2016; Oyeyemi et al., Citation2020; Corroon et al., Citation2016; IntegratE, Citation2021; WHO, Citation2008).

PPMVs’ perception of the accreditation programme

PPMVs stated that they had gained significantly from the project and stated several benefits earned, including increased client flow, increased revenue, access to quality drugs, and improved business management skills, since joining the accreditation programme. PPMVs were willing to continue with the accreditation programme because of the benefits they ascribed to the programme, and expressed willingness to pay for it if the required amount was affordable.

Perceptions of community women

The perceptions of the participating community women were presented under two broad themes: the value of PPMVs as FP service providers at the community level, and barriers to FP service uptake.

Value of PPMVs as FP service providers at the community level

Acceptance of PPMVs as FP service providers was high in Kaduna and Lagos, where the accreditation programme had been implemented for four years by the IntegratE project. Community women attested to the accessibility and improved awareness of FP options within their communities because of the trained PPMVs.

Access to modern contraceptives

Access to modern contraceptive methods was identified as a key factor in FP in the community. Providing access to modern contraceptives through PPMVs facilitates the last mile availability of safe and effective FP services.

Knowledge and awareness of modern contraceptive options

Knowledge of modern FP methods was high among the respondents, with a significant number of women using modern contraceptives for child spacing. Most agreed that their knowledge and awareness of FP mainly came from hospitals and clinics after they had given birth, PPMVs in the communities, and health outreaches and talks during polio immunisation programmes.

… during polio and vaccines. During women gatherings, you’ll hear testimonies from women who successfully did the planning and those who failed and things like that. - A participant from Kaduna

Barriers to family planning uptake

The women identified several significant barriers within the communities, including fear due to perceived side effects, myths and misconceptions, financial constraints, and lack of decision-making power.

Fear of side effects

Fears of perceived side effects existed within the communities, with community women giving instances of their fellow women and family members.

Some people say they feel pain when they insert the implants, and they say it means that the family planning is not working - A participant from Lagos

I did a 3-month injection, I started experiencing too much/frequent bleeding, the time frame for the spacing exceeded 3 months, and I got blood pressure (BP), and I didn’t have it before I started FP - A participant from Kaduna

Financial constraints

Financial constraints were also significant barriers perceived by the community women to access FP services at the community level. These included the costs of transportation to the hospital or service delivery point, consumables, and FP products.

They asked me to pay N2,000, I told them I had only N1,500, I had to beg them so much before they did it for me- A participant from Kaduna

Myths and misconceptions

Myths and misconceptions about FP posed a significant problem for the uptake of modern FP services within the community.

Sometimes a woman may wish to do it, but she’ll hear stories like, one woman did it, and she started bleeding uncontrollably, so she will decide not to do it again - A participant from Lagos

Decision-making on FP uptake

Decision-making on FP by women was a significant barrier for its uptake within the community. Although most women participants in our study affirmed making FP decisions with their husbands, a few were not allowed to do so, and others used contraceptives without consent.

My husband didn’t want family planning because he said three children was not enough, but after a while, I convinced him we needed to space our children, and I went on family planning until I was ready to give birth to the next child – A participant from Lagos

Conclusion

This study shows that service-providers in the for-profit private sector, such as PPMVs, are willing to continue participating and pay for accreditation programmes and that adherence to such programmes is hindered or enhanced by sociodemographic factors. Therefore, it is imperative that donors, stakeholders, and implementing partners consider exploring opportunities to transition the costs of the programme to PPMVs based on their ability to pay, while also considering relevant sociodemographic factors when designing the next phases of the programme implementation or other similar health intervention programmes.

Most PPMVs were willing to be accredited; however, increased monetary benefits such as business improvement, access to quality products and increased stock are benefits that increase the willingness of PPMVs to pay for the accreditation. PPMVs’ demographics such as implementing state, health qualification, and operating years are the variables that should be considered for the success of such programmes, as they have indirect effects on the perceived monetary benefit of the programme and willingness to be accredited and pay for the accreditation.

Benefits associated with accreditations that directly result in increased revenue margins for PPMVs are also necessary to incentivize the private sector to conform with the regulations. This will enhance collaboration between the public and private sectors to achieve to goals of universal health- coverage (UHC). PPMVs also generate the maximum revenue from malaria case management, highlighting their potential role in health intervention programmes targeted at malaria prevention and treatment.

Despite the satisfaction of community women with services offered by accredited PPMVs, fear of side effects, lack of support from male members for FP, myths and misconceptions, and lack of access to modern contraceptives are some factors that continue to hamper the uptake of FP services through private sector providers. There is a need to address these challenges to ensure that programme objectives and health outcome targets are achieved.

Improving PPMVs’ capacity to provide FP services and facilitating value propositions for their businesses in the process has demonstrated promising gains (OlaOlorun et al., Citation2022). In Nigeria’s journey towards improving primary health services and bridging existing gaps in FP service delivery, it is important that donors, policymakers, and implementing partners explore implementation at scale, while also considering appropriate incentives that will ensure the sustainability of health intervention programmes, especially for other priority diseases.

Implication for programme design and implementation

Based on the findings of this study, we emphasise the need to consider the following in future accreditation programmes seeking to expand access to essential health services through informal private sector providers, such as PPMVs:

Incorporating value-added benefits such as business improvement, access to quality products and increased stock are benefits that increase private sector providers’ willingness not only to participate in the accreditation programme, but also pay for it.

Considering the socio-demographic differences across geographies, indicators such as the region/state, qualification, religion, and legal frameworks for implementing such programmes may affect private sector service providers’ participation.

Exploring opportunities to transition programme implementation costs to private sector providers in situations where there is a significant willingness to pay will enhance sustainability.

Including finance and financial management capacity building will improve financial bookkeeping practices and enhance the objective measure of the ROI, cost-effectiveness, and opportunity cost for future programmes.

Incorporating community women’s suggestions in programme design will ensure that private sector providers provide good quality, context-appropriate, and respectful care and are also better equipped to provide counselling services to help address societal norms that may hinder demand for services, especially FP.

Limitations of the study

Due to the generally low academic qualifications of PPMVs, we were unable to objectively measure the specific financial ROI of the study participants. However, great effort was taken to ensure accuracy and reliability of our findings.

There are key aspects of the study that highlight gaps in the study approach. Some of them include the inability to access a larger number of rural PPMVs in the states. For example, Lagos was more of a metropolitan city with a small distribution of rural communities, while Kaduna State with a larger distribution of rural PPMVs had several packets of security challenges in those areas.

The study population comprised only PPMVs enrolled into the IntegratE accreditation programme. Therefore, it will be of great scientific and implementation benefit to evaluate the drivers and barriers to expansion of the programme; and unwillingness of PPMVs to join the accreditation programme.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all study participants who took part in this assessment. We would like to acknowledge the Lagos and Kaduna State Ministries of Health, the Pharmacy Council of Nigeria and IntegratE, for their support and collaboration during the course of this study.

Disclosure statement

Emeka Okafor is the Chief of party of the IntegratE programme at Society for Family Health, Nigeria. Emily Olalere is the Director of Programmes at the PCN, the government arm that directly implements the programme. However, neither of the two authors were directly involved in the analysis/assessment in this study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abubakar, I., Dalglish, S. L., Angell, B., Sanuade, O., Abimbola, S., Adamu, A. L., Adetifa, I. M. O., Colbourn, T., Ogunlesi, A. O., Onwujekwe, O., Owoaje, E. T., Okeke, I. N., Adeyemo, A., Aliyu, G., Aliyu, M. H., Aliyu, S. H., Ameh, E. A., Archibong, B., Ezeh, A., … Zanna, F. H. (2022). The lancet Nigeria commission: Investing in health and the future of the nation. Lancet, 399(10330), 1155–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02488-0

- Asakitikpi, A. E., & Asakitikpi, A. E. (2019). Healthcare coverage and affordability in Nigeria: An alternative model to equitable healthcare delivery. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.85978.

- Belfield, C., & Levin, H. M. (2010). Cost-benefit analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. In International encyclopedia of education (pp. 199–203). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01245-8.

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychology Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Berendes, S., Adeyemi, O., Oladele, E. A., Oresanya, O. B., Okoh, F., & Valadez, J. J. (2012). Are patent medicine vendors effective agents in malaria control? Using lot quality assurance sampling to assess quality of practice in jigawa, Nigeria. PLoS One, 7(9), e44775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044775

- Beyeler, N., Liu, J., & Sieverding, M. (2015). A systematic review of the role of proprietary and patent medicine vendors in healthcare provision in Nigeria. PloS One, 10(1), e0117165. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117165

- Breslin, G., & McKeown, C. (2022). Cloud-based definition and meaning. Harper Collins Publishers. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/patent-medicine.

- Brieger, W. R., Osamor, P. E., Salami, K. K., Oladepo, O., & Otusanya, S. A. (2004). Interactions between patent medicine vendors and customers in urban and rural Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning, 19(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czh021

- Chen, F., Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Kirby, J., & Paxton, P. (2008). An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 36(4), 462–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108314720

- Claypoole, V. L., Neigel, A. R., & Szalma, J. L. (2017). Perceptions of supervisors and performance: A thematic analysis. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 61(1), 1740–1744. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541931213601916

- Corroon, M., Kebede, E., Spektor, G., & Speizer, I. (2016). Key role of drug shops and pharmacies for family planning in urban Nigeria and Kenya. Global Health: Science and Practice, 4(4), 594–609. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00197

- Creswell, W. (2022). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches, 2, 2007. Retrieved September 26, from https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID = 1807302.

- Fajola, A., Asuzu, M. C., Owoaje, E. T., Asuzu, C. C., Ige, O. K., Oladunjoye, O. O., & Asinobi, A. (2011). A rural-urban comparison of client-provider interactions in patent medicine shops in south west Nigeria. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 32(3), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.2190/IQ.32.3.c

- Haveman, R. H., & Weimer, D. L. (2001). Cost–benefit analysis. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 2845–2851). https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-043076-7/02239-7.

- Iheoma, C., Daini, B., Lawal, S., Ijaiya, M., Fajemisin, W., Iheoma, C., Daini, B., Lawal, S., Ijaiya, M., & Fajemisin, W. (2016). Impact of patent and proprietary medicine vendors training on the delivery of malaria, diarrhoea, and family planning services in Nigeria. Open Access Library Journal, 3(8), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4236/OALIB.1102404

- IntegratE. (2021). Heterogeneity of PPMVs and implication for family planning services in Lagos and Kaduna states: A case study of the IntegratE project and the Pharmacists Council of Nigeria’s 3 Tier - Accreditation system of PPMVs. https://integrateeproject.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IntegratE-Project-Policy-Brief-2021.pdf.

- Kee, J. E. (2004). Cost-Benefit analysis. In Encyclopedia of social measurement (pp. 537–544). https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00175-4.

- Khan, S. N. (2014). Qualitative research method: Grounded theory. International Journal of Business Management, 9(11), 224. https://doi.org/10.5539/IJBM.V9N11P224

- Lee, M. (2021). The barriers to using modern contraceptive methods among rural young married women in moshi rural district, the Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 25(4), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i4.11

- Livinus, C., Ibrahim, M., Isezuo, S., & O Bello, S. (2010). The impact of training on malaria treatment practices: A study of patent medicine vendors in birnin-kebbi. Sahel Medical Journal, 12(2), https://doi.org/10.4314/smj2.v12i2.55663

- Masters, R., Anwar, E., Collins, B., Cookson, R., & Capewell, S. (2017). Return on investment of public health interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(8), 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-208141

- National Bureau of Statistics, UNICEF, & UNFPA. (2013). Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (Nigeria) 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2022 [Online], from https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/reports/nigeria-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-mics-2011.

- National Population Commision, National Malaria Control Programme, Measure DHS, I. I. (2012). National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) [Nigeria], and ICF International. 2012. Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) 2010 Abuja Nigeria National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], National Malaria Co. https://www.scirp.org/(S(lz5mqp453edsnp55rrgjct55))/reference /ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID = 2298468.

- Nigerian Population Commission (NPC). (2009). Nigeria demographic and health survey 2008. https://ngfrepository.org.ng:8443/handle/123456789/3140.

- Noble, H., & Mitchell, G. (2016). What is grounded theory? Evidence-Based Nursing, 19(2), 34–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2016-102306

- NPC/ICF. (2018). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF; 2019 - Google Search. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/search?q = National+Population+Commission+%28NPC%29+%5BNigeria%5D%2C+ICF.+Nigeria+Demographic+and+Health+Survey+2018.+Abuja%2C+Nigeria%2C+and+Rockville%2C+Maryland%2C+USA%3A+NPC+and+ICF%3B+2019&source = hp&ei = mDmjYc77Da-GjLsPwMewIA&ifls.

- Okeke, T. A., & Okeibunor, J. C. (2010). Rural–urban differences in health-seeking for the treatment of childhood malaria in south-east Nigeria. Health Policy, 95(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.005

- Okeke, T. A., Uzochukwu, B. S. C., & Okafor, H. U. (2006). An in-depth study of patent medicine sellers’ perspectives on malaria in a rural Nigerian community. Malaria Journal, 5(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-5-97

- OlaOlorun, F. M., Jain, A., Olalere, E., Daniel-Ebune, E., Afolabi, K., Okafor, E., Dwyer, S. C., Ubuane, O., Akomolafe, T. O., & Baruwa, S. (2022). Nigerian stakeholders’ perceptions of a pilot tier accreditation system for patent and proprietary medicine vendors to expand access to family planning services. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08503-3

- Onwujekwe, O., Chukwuogo, O., Ezeoke, U., Uzochukwu, B., & Eze, S. (2011). Asking people directly about preferred health-seeking behaviour yields invalid response: An experiment in south-east Nigeria. Journal of Public Health, 33(1), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdq065

- Onwujekwe, O., Hanson, K., & Uzochukwu, B. (2011). Do poor people use poor quality providers? Evidence from the treatment of presumptive malaria in Nigeria. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 16(9), 1087–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02821.x

- Oyeyemi, A. S., Oladepo, O., Adeyemi, A. O., Titiloye, M. A., Burnett, S. M., & Apera, I. (2020). The potential role of patent and proprietary medicine vendors’ associations in improving the quality of services in Nigeria’s drug shops. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 567. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05379-z

- Parry, S. (2020). Fit Indices commonly reported for CFA and SEM. Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit: Cornell University, 2. https://www. cscu. cornell. edu/news/Handouts/SEM_fit. Pdf.

- Pek, J., Wong, O., & Wong, A. C. M. (2018). How to address non-normality: A taxonomy of approaches, reviewed, and illustrated. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2104. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2018.02104/BIBTEX

- Pharmacists Council of Nigeria. (2020). Patent and Proprietary Medicine Vendors (PPMVs). REGISTRATION AND LICENSING. Procedures and Guidelines. https://www.pcn.gov.ng/registration-and-licensing/patent-and-proprietary-medicine-vendors-ppmv/.

- Pharmacy Council of Nigeria- About Us. (2022). Pharmacy Council of Nigeria. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://www.pcn.gov.ng/about-us/.

- Prach, L. M., Treleaven, E., Isiguzo, C., & Liu, J. (2015). Care-seeking at patent and proprietary medicine vendors in Nigeria. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0895-z

- Randrianasolo, B., Swezey, T., Van Damme, K., Khan, M. R., Ravelomanana, N., Lovaniaina Rabenja, N., Raharinivo, M., Bell, A. J., Jamieson, D., MAD STI Prevention Group, & Behets, F. (2008). Barriers to the use of modern contraceptives and implications for woman-controlled prevention of sexually transmitted infections in Madagascar. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(6), 879–893. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932007002672

- Shi, D., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Rosseel, Y. (2020). Assessing Fit in ordinal factor analysis models: SRMR vs. RMSEA. Structural Equation Modeling, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1611434

- Sinai, I., Omoluabi, E., Jimoh, A., & Jurczynska, K. (2020). Unmet need for family planning and barriers to contraceptive use in kaduna, Nigeria: Culture, myths and perceptions. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(11), 1253–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1672894

- Tanaka, S., & Huba, G. J. (1985). A fit index for covariance structure models under arbitrary GLS estimation. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38(2), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1985.tb00834.x

- Thummalachetty, N., Mathur, S., Mullinax, M., DeCosta, K., Nakyanjo, N., Lutalo, T., Brahmbhatt, H., & Santelli, J. S. (2017). Contraceptive knowledge, perceptions, and concerns among men in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 792. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4815-5

- Treleaven, E., Liu, J., Prach, L. M., & Isiguzo, C. (2015). Management of paediatric illnesses by patent and proprietary medicine vendors in Nigeria. Malaria Journal, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0747-7

- Uguru, N. P., Onwujekwe, O. E., Uzochukwu, B. S., Igiliegbe, G. C., & Eze, S. B. (2009). Inequities in incidence, morbidity and expenditures on prevention and treatment of malaria in southeast Nigeria. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-9-21

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2008). Task shifting: Rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: Global recommendations and guidelines. WHO; © 2008 World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43821/9789241596312_eng.pdf.