ABSTRACT

An emerging body of literature examines multiple connections between water insecurity and mental health, with particular focus on women’s vulnerabilities. Women can display greatly elevated emotional distress with increased household water insecurity, because it’s them who are primarily responsible for managing household water and uniquely interact with wider water environments. Here we test an extension of this proposition, identifying how notions of dignity and other gendered norms related to managing menstruation might complicate and amplify this vulnerability. Our analysis is based on systematic coding for themes in detailed semi-structured interviews conducted with twenty reproductive-age women living in two water insecure communities in New Delhi, India in 2021. The following themes, emerging from our analysis, unfold the pathways through which women’s dignity and mental health is implicated by inadequate water: ideals of womanhood and cleanliness; personal dignity during menstruation; hierarchy of needs and menstruation management amidst water scarcity; loss of dignity and the humiliation; expressed stress, frustration and anger. These pathways are amplified by women’s expected roles as household water managers. This creates a confluence of gendered negative emotions – frustration and anger – which in turn helps to explain the connection of living with water insecurity to women’s relatively worse mental health.

Introduction

Safe and adequate household water is important not only for physical, but also for mental health. A growing body of literature observes that the experience of living with water insecurity is highly associated with expressions of emotional and psychological distress, including symptoms of common mental disorders like anxiety and depression (Wutich et al., Citation2020). As a social, economic, physiological, and environmental resource, water likely affects mental health through multiple pathways (Boazar et al., Citation2019; Collins et al., Citation2019; Krumdieck et al., Citation2016; Rosinger et al., Citation2021; White et al., Citation2021; Wutich & Brewis, Citation2014; Wutich, Jepson, et al., Citation2022; Wutich, Rosinger, et al., Citation2022). The repeated observation, that it is women who particularly show associations between stress/distress and water insecurity has flagged this as a gendered phenomenon (Achore & Bisung, Citation2022; Bisung & Elliott, Citation2016; Brewis et al., Citation2020; Cooper-Vince et al., Citation2018; Duignan et al., Citation2022; Harris et al., Citation2017; Radonic & Jacob, Citation2021; Stevenson et al., Citation2012; Sultana, Citation2011; Tallman, Citation2019; Workman & Ureksoy, Citation2017; Wutich & Ragsdale, Citation2008; Wutich et al., Citation2022). The gender differences in the apparent stress/distress effects can be profound. For example, in a nationally-representative study of water insecurity in Nepal that matched men and women in the same households, women had significant stress effects associated with reduced household water access but men had none (Brewis et al., Citation2019a). Such findings are mostly from the global south, but similar observations have been made in water insecure settings in advanced industrialised nations (Duignan et al., Citation2022; Gaber et al., Citation2021).

This gendered pattern likely emerges from the fact that it is most often the women who are responsible for managing household water (Trivedi, Citation2018; Watts, Citation2004). A few studies are worth highlighting here. Using a feminist political ecological approach, Sultana (Citation2011) explicates the multiple emotions that women in rural Bangladesh experience while navigating a series of social negotiations to meet their households’ water needs. Sultana (Citation2011) describes women’s lived experiences of conflict, and the fear and stress that women undergo while fetching household water. In a study in Ethiopia, Stevenson et al. (Citation2012) show that women’s responsibility for managing water for their households makes them susceptible to heightened measures of emotional distress. The authors underscore the cultural dimension of water insecurity that surfaces in women’s experiences of emotional distress and shame. Several studies have examined the connections between water and social and community conflict in different sociocultural contexts (Bijani & Hayati, Citation2015; Boazar et al., Citation2019; Veisi et al., Citation2020). Pearson et al. (Citation2021) analysed large-scale survey data in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and found that water insecurity was responsible for the manifestation of inter-personal conflict both within and outside households, with likely adverse mental health outcomes. A few studies have also used survey data to quantitatively establish the relationship between household water insecurity and mental health outcomes for women. For example, in their study based in Nepal, Tomberge et al. (Citation2021) found a clear association between the physical burden of carrying water and women’s psychosocial health in that too much water carrying produced emotional distress and reduced functional capacity. Using data collected through geographically randomised surveys in three high-poverty communities in Haiti, Brewis et al. (Citation2019b) established a robust association between inadequate household water insecurity and depression and anxiety among women in both rural and urban areas. Another study using a large, nationally-representative sample of households in Nepal (Choudhary et al., Citation2020) found that limited household water access resulted in women’s increased exposure to intimate partner violence, both physical and emotional, likely causing a decline in women’s psychosocial health and creating another mechanism linking water insecurity with stress among women. Nearly all of these studies investigate and highlight women’s mental health and emotional distress in relation to their failures to meet social and familial obligation towards water-related roles and responsibilities when living with water insecurity.

A more extensive, parallel literature, primarily in the WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) sector, has established that managing menstruation under conditions of limited sanitation (defined in part by lack of access to adequate water) is also in itself very stressful (Alexander et al., Citation2018; Asumah et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Behera et al., Citation2022; Caruso et al., Citation2017; Hussein et al., Citation2022; Pouramin et al., Citation2020; Torkan et al., Citation2021). Lack of sanitary facilities, including lack of water, has commonly been described as a barrier to menstrual hygiene (e.g. Ademas et al., Citation2020; Alexander et al., Citation2018; Chinyama et al., Citation2019; Ndlovu & Bhala, Citation2016; Oduor et al., Citation2015; Sommer & Kirk, Citation2008). Sometimes this has more broadly been referred to as one key aspect of ‘sanitation insecurity’: lack of adequate and appropriate resources for the hygienic management of menses in ways that foster dignity (Jalali, Citation2021; O’Reilly & Dreibelbis, Citation2018; Walters, Citation2014; Workman et al., Citation2021). For example, in a study of Haitian households, Brewis et al. (Citation2019b) showed that the association between water insecurity and depression symptoms was partially mediated by sanitation insecurity. While this case had a larger sample size, however, it had a very basic measure of sanitation insecurity (lack of a toilet) that did not address the role of menstrual dignity specifically.

Lack of menstrual dignity, stemming from inadequate sanitary resources or facilities, is widely recognised as undermining not just emotional wellbeing but the ability to participate more widely in society, such as education and employment (Davis et al., Citation2018; Miiro et al., Citation2018; Sivakami et al., Citation2019; Tegegne & Sisay, Citation2014; Yaliwal et al., Citation2020). However, there are relatively fewer studies that look at how women’s inability to meet menstrual needs can impact their social and psychological well-being (Hennegan et al., Citation2016). Based on a few preliminary studies, this is found to be associated with manifestations of emotional harm, including negative mental health impacts (Caruso et al., Citation2017; Hirve et al., Citation2015; Hulland et al., Citation2015). Cardoso et al. (Citation2021), in their work based in the United States, examined the more focused phenomenon of ‘period poverty’ – some women’s inability to afford sanitary products – and the ways in which this impacted the women’s mental health, notably in an increase in reported risk for depression. The physical dimensions of menstruation – its cyclical nature, any irregularities in these cycles, as well as premenstrual symptoms – have received greater attention in this regard and are found to have consequences for psychological stress and/or psychiatric disorder, especially among young women (Fukushima et al., Citation2020; Jang & Elfenbein, Citation2019; Maurya et al., Citation2022; Yilmaz et al., Citation2021). In addition, the evidence around the taboos, shame, and embarrassment associated with menstruation also provides a key pathway that potentially connects menstruation with women’s mental health (Hennegan et al., Citation2016; Mason et al., Citation2013). Here, an inability to manage menstrual constraints, together with loss of dignity, experiences of humiliation, has been observed to affect young girls’ school performance and to produce emotional stress in multiple contexts (Fialkov et al., Citation2021; Vashisht et al., Citation2018).

Dignity, conceptualised as a felt experience and signal to the self that one has worth and value, is an especially useful construct for understanding water-related distress as one central aspect of such stigma processes around sanitation/menstruation, especially because it then intersects with the possession and experience of having lower power relative to others (in this case, directly related to gender status). Low power is so fundamental to health-related stigma that some theorise that without low power there is no stigma (Brewis & Wutich, Citation2020; Link & Phelan, Citation2014). Dignity is theorised to be an especially crucial source of resistance and challenge to self-stigma. Self-stigma is the form of stigma with the most direct pathway to emotional stress and thus likely harmful to mental health (Brewis & Wutich, Citation2019). Dignity is therefore potentially an especially effective form of complex stigma self-management because it creates a bridge between stigmatised and unstigmatised individuals (e.g. Jensen, Citation2018). In this sense, dignity relies on individual constructions of (a positive) self in relation to others and perceived social norms. Dignity restoration is often positioned as a central strategy in health-related anti-stigma efforts that target affected individuals (for a menstruation example see Soeiro et al., Citation2021), especially where very low power makes other forms of resistance (like "community building or resisting/dismantling disempowering institutions" (see Friedman et al., Citation2022), extremely difficult.

Taken as a whole, these studies point to the need to theorise in a more detailed way about why water insecurity affects women’s emotional and mental health so uniquely, despite them being situated in similar water context as their men counterparts. Guided by this goal, we use systematically analyse women’s own narratives of menstrual management to explore in greater detail its emotional contexts, with a careful attention to the role of women’s sense of and efforts to maintain dignity and related ideas of how a responsible woman should be. Our research context is an relevant one: married women living in highly water insecure neighbourhoods in urban India, where they must navigate both a lack of basic sanitation facilities and potentially stringent social norms and rules regarding menstrual hygiene.

Materials and methods

Research team

The research team consisted of seven full-time researchers (including the lead author), two PhD students, and two field assistants. The two field assistants and the lead author live in India, where the research upon which this paper is based was conducted. The research team brings a range of interdisciplinary expertise in menstruation, water insecurity, stigma, mental health, site-specific geographic/regional knowledge, and ethnographic methods. The two field assistants were recruited by first author to conduct interviews with participants and transcribe data. These field assistants were given training on the interview protocol, including through pilot data collection in the field. This pilot fieldwork was supervised by the first author and also helped in establishing relationships within the studied communities.

Research site and study population

The study sites for this paper were two water-scarce community neighbourhoods located in the city of New Delhi in India.Footnote1 The neighbourhoods were Taimoor Nagar and Batla House (hereafter TN and BH), both older neighbourhoods that depend primarily upon inadequate municipal water. The study recruited twenty women aged between 18 and 40 years, with a goal of capturing some diversity of socioeconomic backgrounds. Prior to recruitment, the research rational, design, and interview protocol were submitted for institutional review. Once approval was obtained, recruitment of participants began. Sample size was set at twenty participants as this number is deemed more than sufficient for theme saturation (the point at which no new themes are identified) for within group comparison (Francis et al., Citation2010; Guest et al., Citation2006; Hagaman & Wutich, Citation2017). The neighbourhoods were selected to capture religious diversity: all respondents in TN were Hindus while the respondents in BH were Muslims. Only women living in households identified as ‘not always having enough water for drinking, cooking, washing, or for other household uses’ were included in the study. The sample included seventeen married and three unmarried women. Women who had not menstruated in three or more years were excluded from the study. A summary of participant demographics is included below in .

Table 1. List of participants in India.

Data collection

The interview protocol was developed based on team expertise and with reference to prior literature (Wutich & Brewis, Citation2019). The interview schedule was developed iteratively and collaboratively among the authors with collective expertise in the field site, language, menstruation, sanitation, water insecurity, mental health/wellbeing, gender, idiomatic language, and text-based analysis. The interview protocol was then cognitively tested with members of the research team and refined, based on feedback. Data was collected by the two field assistants in TN and BH in the year 2021. Two interviews were initially collected and transcribed to check their quality and to confirm that the protocol was capturing the intended information. This step did confirm that the protocol was operating according to the intent of the research team. In-depth interviews using the same extensive semi-structured protocol were then conducted with all twenty women. The interviews were recorded; all were conducted in Hindi, the preferred language of the participants. Interviews were designed to capture in detail women’s experiences and perspectives across several intersecting domains: managing menstruation, living with water insecurity, experiencing and communicating distress and emotion, notions of ideal and acceptable womanhood, and resiliency/resistance.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed first in the original language. We translated the interview data into English to facilitate cross-cultural analysis and then developed a codebook (Wutich et al., Citation2021). Translations were constantly checked by first author as the codebook was applied, to ensure accuracy and to ensure correct interpretations of idiomatic representations.

The first three authors individually read through the transcripts, meeting bi-weekly over a period of two months to deliberate and discuss key themes within and across the domains of inquiry (Bernard et al., Citation2016). Initial identified themes included maintenance of dignity, ideal menstruation management, and articulated stress/distress while living with household water insecurity. A subsample of the interviews were first coded by second author; then, the first three authors met to discuss the application of the codes, refining the codebook iteratively and collaboratively until we agreed on a finalised codebook. Coding was completed by second author and checked by authors one and three; any disagreements in code assignments were resolved through discussion. Samples of codes are provided in . Coding was done in MaxQDA v. 20.

Table 2. Examples of codes applied in analysis.

Findings

We identified five themes in the interview data. These themes were: (1) Ideals of womanhood and cleanliness; (2) Personal dignity during menstruation; (3) Hierarchy of needs and menstruation management amidst water scarcity; (4) Loss of dignity, which included expressed feelings of humiliation, shame, and worry; and (5) Expressed stress, frustration, anger. There are natural areas of overlap between these five themes, and interviewee’s responses sometimes fell into multiple categories. Taken together, these themes illustrate women’s ideas of what constituted a responsible women and dignified conduct during menstruation, the importance of water in realising this notion, and women’s experienced mental stress and shame when water is not adequate to meet the needs of responsible conduct.

Ideals of womanhood and cleanliness

The women voiced remarkably similar ideas about what constituted ‘responsible’ (‘jimmedar’) and ideal conduct with respect to menstruation management and associated cleanliness and hygiene concerns. For example, in response to an interview prompt asking, ‘How do you think a responsible woman will maintain her cleanliness and hygiene during menstruation?’ one woman (Interviewee 4) expressed a typical sentiment about the importance of physical health and ridding oneself of toxins when she responded, ‘She must keep clean … in this [menstruation], bodily toxins only are discharged no; the more you keep clean, the more will you be away from disease’. However, in their responses to this prompt, a greater number of women not only focused on cleaning their bodies, but also on the proper disposal of menstruation-related waste, all while hiding the fact that they were menstruating. This last point was particularly important in interviewee responses. For example, one woman (Interviewee 2) said, ‘The right way is to bathe early in morning … [and a woman] should use pad [and she] should change the pad in 2–3 hours … Then when it is waste … it should be covered in a paper and then should be thrown in the dustbin’. Similarly, another woman (Interviewee 3) said, ‘She should keep clean, should throw [her pad] in dustbin, she should first wrap [it] in paper … [because] men should not see [the pad]’.

In women’s responses to the prompt asking, ‘How do you think a responsible woman will maintain her cleanliness and hygiene during menstruation?’ the focus is on the pragmatic aspects of cleaning and disposal, but with an additional focus on discretion. An underlying concern for women appeared to be their felt responsibility to ensure that others, especially men, should not know they were menstruating. Many women noted that ‘bad’ (‘sharmnak’) practices around menstruation management included the use of soiled cloths instead of disposable pads or clean cloths, lack of frequent bathing, and lack of discretion in managing menstruation blood and soiled products.

Personal dignity during menstruation

In the narratives, women linked socially appropriate conduct during menstruation with the maintenance of their own dignity. A common concern was once again on preventing others, especially men, from being made aware of menstruation – although there were some variations in responses around this point. Some women felt that menstruation needed to be hidden from all non-family members (i.e. husbands and mothers and daughters often knew), while others expressed the belief that menstruation needed to be hidden from all men. One such interviewee (Interviewee 1) commented, ‘She [the dignified woman] should stay properly … there should not be stains on cloths. She should walk properly so any traces are not left … what will happen if others, especially men happen to see, what will they think?!’ Another woman (Interviewee 7) said, ‘No one should know that something like this [blood] is there … that she is not pure’. Yet another (Interviewee 15) took up this idea, saying, ‘It matters that stains should not be visible to anyone. Father or brothers don’t come to learn about it – we should respect them … She [the dignified woman] should keep clean. She should not pollute the surroundings, she should be careful that men do not come to know that she is menstruating’. In these narratives, pragmatic aspects of dignified conduct, i.e. blood stains on outer wear needed to be avoided at all costs, interwove with less pragmatic ideas about a menstruating woman as a source of household and familial pollution. Both the stains and the pollution were what a dignified woman needed to manage, according to the women with whom we spoke, for example, by avoiding touching anything considered holy and by not allowing menstrual blood to make visible stains.

Hierarchy of needs and menstruation management amidst water scarcity

An important theme captured in the interviews revolved around what was needed to maintain menstruation with dignity, according to the twenty women interviewed. Sanitary pads and water were the two most important items women said they needed for managing their menstruation in a dignified way. Other necessities commonly mentioned included laundry and hand soap, private toilets, and appropriate undergarments.

This hierarchy of needs in which water was dominant was reflected in many of the longer interview excerpts. In response to the question, ‘Can you provide some reason why a woman might be unable to keep clean?’ one respondent (Interviewee 1) gave a typical response, saying, ‘Due to [the] water problem … we can’t bathe daily’. Similarly, another woman (Interviewee 2) stated, ‘Water is the biggest problem … due to lack of water, I cannot keep myself clean, as desired’. Yet another woman (Interviewee 4) said, ‘Here in Delhi, water is a problem, there is no regular supply … water comes by tankers; water does not come on time’. When asked whether women needed more water when menstruating, the first respondent (Interview 1) said, ‘Yes … [but] it’s problematic to bathe [because of chronic water shortages]; I skip it or just clean partially’.

Women reported that they had to adopt multiple strategies to cope with their lack of water. Some interviewees, as we saw from the preceding quote, were forced to limit their bathing. Another strategy centred on storing and allocation within the household. One woman (Interviewee 13), for example, when she was asked who she would give water to first within the household, responded, ‘As per need, I will give water first to myself … because I will be impure due to menstruation. I need to clean myself’. Another common management mechanism was to avoid doing household tasks such as mopping or washing dishes in order to have enough water to keep clean during menstruation. For example, one respondent (Interviewee 3) said, ‘A woman has to manage. Somehow, I also manage; I use little water, avoid washing activities’. Lastly, women reported drawing from different sources when they needed extra water to manage menstruation. A woman (Interviewee 1) was asked, for instance, if she did anything other than purchase more water during menstruation and she responded, ‘I save water in stock … when possible … I try to manage as best I can, but that the situation is very difficult’. Another woman (Interviewee 6) responded to this question with, ‘My friend’s household has a tap … so I go there and collect’. The interviewer clarified, ‘So, you borrow?’ and the woman responded, ‘Yes, [from] my friend’s tap or the neighbor’s water container’.

Loss of dignity, including feelings of humiliation, shame, and worry

Given the importance of water in the hierarchy of needs for ‘proper’ menstruation management – management that adhered to local notions of dignity and cleanliness – the persistent lack of water felt by households in these neighbourhoods produced an array of negative emotions among the women interviewed. Humiliation, shame, and worry about a perceived loss of dignity (or the possibility of a future loss of dignity) were reported in virtually all twenty interviews. Women reported that menstruation in a water-scarce context had the potential to cause a loss of their personal dignity (‘izzat’) and therefore, they experienced felt shame and humiliation in two ways: directly (e.g. via stained clothes potentially seen by others) and indirectly (e.g. via daily chores left undone to reallocate water to menstrual hygiene).

Various respondents expressed that they were not able to clean themselves promptly or thoroughly, instead having to wait for water and/or clean inadequately. Inability to clean oneself properly was expressed as emotionally distressing by all twenty women. All of them stated that it would be ‘embarrassing’ and even ‘humiliating’ if others saw blood stains on their clothes or evidence of soiled pads or cloths. For example – one woman said ‘if her stains are visible to anyone, this can be humiliating [apmaanjanak]’. When an interviewer asked a woman (Interviewee 4) how she managed menstruation when there was not enough water, the woman asked rhetorically, ‘How will I clean everything during those days?! … Because cloths are spoiled, it becomes very problematic, you know’.

Some women said that they also found it humiliating if someone visited them while they were compromising on household cleaning and washing in order to meet menstruation needs. Diverting water away from other household usage for menstrual needs was common practice because water was so scarce but it was not considered ideal. Compromising on household chores in order to manage water for menstrual needs may have allowed a woman to clean herself to an acceptable extent but the house then remained dirty. Personal hygiene versus house hygiene was a delicate balancing act for many women since cleanliness of both kinds was considered essential for dignified, responsible women. One respondent (Interviewee 5) explained, ‘When water is not there, dishes are not washed and when someone visits and asks me why I am not cleaning them, I feel ashamed. How will I clean the dishes when water is not there!’

Expressed stress, frustration, and anger

Systemic lack of water could trigger negative emotions such as stress, frustration, and anger among the women interviewed. At the same time, however, menstruation itself was experienced as a time of elevated frustration, anger, and other negative emotions. When water scarcity and menstruation combined, the effects on women were significant, as expressed across all twenty interviews. For example, upon being asked, ‘How do you feel about the water situation in your household, when you menstruate?’ one woman responded, ‘I feel very bad when water is not there. I am anxious and tensed, and I wish water comes from somewhere’. To the same question, another woman (Interviewee 6) answered, ‘I feel very angry … Why no water in our tap, some households get water in their taps, why not in our tap? … I am sad, worried and angry at the same time’. Similarly, a third woman (Interviewee17) stated, I feel very angry. Why? Why we don’t get enough water here? Nowhere [do] people face such lack of water, the way we do. Why can’t water supply pipes be laid out here? … and I feel like hitting someone. Who is responsible for our misery?! One young woman (Interviewee 14) summarised the situation: ‘I feel bad. We have to think and plan even for bathing and drinking … It’s not a good feeling. I feel bad, at least during periods. In such a water situation, you can’t work freely’.

All those interviewed talked in detail and at length about how stressful menstruation management was when faced with insufficient water. As one woman (Interviewee 14) said, ‘I feel bad, but I feel angry more; how will I clean everything during those days?’ All of the women noted that menstruation was the proverbial final straw in terms of the extra water demands necessitated by managing menstrual blood. As one woman (Interviewee 18) remarked, ‘When water is not there, I feel very angry … I just feel angry and irritated … because when water runs out I have to call him [her husband]. He comes from duty [work] and then fetches water’. This implied that she had to wait to clean herself until her husband arrived and brought water. Such episodes of uncleanliness, coupled with helplessness to get rid of the dirt, blood, and perceived pollution, were frequent for most of the women interviewed. During these episodes, they could not comfortably interact with anyone and angry frustration was very high. Most of this expressed anger and frustration was not directed at family members or neighbours, many of whom were also facing such challenges. Instead, it was more general and diffuse – but nonetheless strongly felt.

Discussion

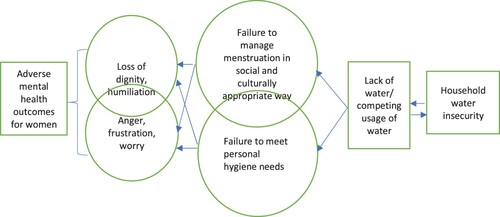

A growing body of evidence underscores the importance of having access to adequate water for good mental health, especially for women’s mental health. Using qualitative data based on the perceptions and experiences of twenty menstrual-age women living in water insecure neighbourhoods in urban India, our study finds that the lack of water during menstruation can be especially emotionally challenging because it violates women’s basic sense of self, especially their dignity (). Furthermore, this connection is mediated by women’s perceived failures in menstrual management in the context of rigid and gendered notions of responsibility and dignity around cleanliness.

Figure 1. Summarised framework linking household water insecurity with loss of dignity and adverse mental health outcomes for women.

To begin with, our findings show that women in the communities we studied, have constant interface with a set of socially acceptable norms around dignified behaviour and ideal cleanliness with respect to menstrual management. These norms were communicated, often through what is already being practiced by other menstruating females, mostly in families or in schools. Public health norms around hygiene and ‘cleanliness’ intersected and overlapped with sociocultural and religious norms around ‘pollution’, ‘dirt’ or ‘unholiness’ (for example- menstruating women were not expected to do prayers or to touch anything considered sacred), producing powerful messages that were reinforced at every turn, even as women acknowledged that the norms were extremely difficult to meet in their everyday lives. Moreover, most of the dictates around hygiene and purity admonished individual women to clean themselves and their own bodies, even as failure to clean reflected on the entire family. Significantly in this context, public health dictates and teaching around hygiene – at least in the absence of adequate water – amplified experienced distress over not meeting norms.

Menstruation norms here centred on cleanliness and hiddenness. Other people, especially men, were not supposed to be made aware that women were menstruating and therefore, keeping clean and avoiding getting stains on clothing were seen as women’s primary responsibilities during menstruation. As expressed by women themselves, inability to adhere to these norms – as they understand and act on them – is a source of potential humiliation, embarrassment, and shame. Felt stigma and shame are two powerful potential drivers of psychosocial stress and thus can greatly undermine women’s mental wellbeing and health (e.g. Cousins, Citation2020; Hall, Citation2021; Sumpter & Torondel, Citation2013). To avoid humiliation, embarrassment, and shame and to manage menstruation with dignity (as they define it), household water and sanitary pads were considered as the most needed items by all the women interviewed. The increasing availability of disposable sanitary pads was one benefit women frequently cited. Lack of water was nonetheless invariably cited as a challenge to dignified menstrual conduct, leading to social humiliation.

Other research has found that norms around women’s responsibilities for managing household water are likely key routes leading to unfavourable mental health for women in water scarce contexts, in part because inability to meet gendered ideals of care for the family causes distress, anxiety, and depression (Brewis et al., Citation2021; Collins et al., Citation2019; Cooper-Vince et al., Citation2018; Stevenson et al., Citation2012; Sultana, Citation2011; Tallman, Citation2019). These approaches focused on water-related distress in relation to broader household roles. Our findings support this conclusion, while focusing on individual navigation of menstruation norms specifically as an additional emotional stressor – a less studied potential pathway connecting household water insecurity to women’s mental health. As expressed by women themselves, inability to adhere to norms of personal hygiene caused humiliation, embarrassment, and shame. In their responses, women were quite direct and explicit in questioning their systemic lack of water and in expressing the associated anger and frustration that they felt. The responses indicate a common bubble of negative emotions – frustration, stress, anger, helplessness, and irritation. Such findings align with other research on ‘period poverty’ (Brinkley & Niebuhr, Citation2022; Medina-Perucha et al., Citation2020; Soeiro et al., Citation2021), which has been found to be associated with negative emotions and severe to moderate depression among young women (Cardoso et al., Citation2021; Gouvernet et al., Citation2023; Vora, Citation2020). We also note that felt stigma is a particularly pernicious factor in emotional stress, associated with elevated risk of common mental disorders, and based in the self-blame we have identified here (e.g. Brewis & Wutich, Citation2020).

Moreover, our interviewees explained how already complex and emotionally distressing situations were made more so because water was also needed for other water-based household chores for which also, women were held responsible. Women reported working out several permutations and combinations to allocate water among those needs, including saving water, stockpiling small amounts of water, borrowing from neighbours, etc. An important strategy in this regard was to avoid other water-based household chores like mopping, and diverting water away for menstrual use. As expressed by the women, living in an ‘unclean’ house by the standards expected was also problematic and embarrassing – and figuring out the different strategies needed to balance personal and household needs was in itself extremely stressful.

By explicating new pathways linking water insecurity to women’s mental health, as mediated by women’s specific menstrual needs in the contexts of wider household ones, our findings provide initial data supporting water-based and gendered interventions to address mental health challenges. In the process, the findings also underscore the importance of water in menstrual management – an important public health issue. In our findings, lack of water also appears to be a sub-set of period poverty. Based on this, both research and policy interventions aiming to address women’s menstruation challenges can broaden the definition of period poverty to accommodate the role of water as a key resource. Finally, the findings present directions for theory-building and testing more hypotheses, linking water, menstruation, and women’s mental health.

Limitations: Our study was a qualitative one, following relevant methodological conventions for sample size (Hennink & Kaiser, Citation2022). This sampling approach does not support research design and data analysis using standardised scales for mental health assessment and therefore we could not measure anxiety and depression symptoms among the studied women. Instead, this study paid close attention to the expressed feelings and articulated emotions of the women, following approaches that study gendered expressions of emotion (e.g. du Bray et al., Citation2019; Sultana, Citation2011). These emotions clearly depict that women, especially during menstruation, live in heightened state of stress bred by household water insecurity and associated challenges.

Conclusion

Global public health initiatives and programming now recognise that mental health is a core component of overall wellbeing and health, both at the individual and at the community level. Challenges to mental health are diverse, complex, and intertwine with other challenges to health and do not depend solely upon individual attributes but also socioeconomic, cultural, political and environmental conditions. Therefore, an over-focus on individualised disorders may miss key stressors in the larger environment and sociocultural milieu. Water insecurity is increasingly recognised as one of those core contextual factors, and one that affects large sections of populations globally. In this paper, we detailed one mechanism whereby water insecurity is particularly distressing/stressful for women; its intersection with menstruation experiences and wider household responsibilities for managing water.

Author contribution

NC, CSS and ST conceptualised the manuscript. Based on iterative discussion with each other – CSS developed the codebooks and analysed data, ST developed the results’ section and NC worked out the introduction and discussion section; All authors reviewed all sections and approved the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The research conducted in the New Delhi sites was part of a larger multi-sited project that also included sites in Bangladesh and Pakistan.

References

- Achore, M., & Bisung, E. (2022). Experiences of inequalities in access to safe water and psycho-emotional distress in Ghana. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114970

- Ademas, A., Adane, M., Sisay, T., Kloos, H., Eneyew, B., Keleb, A., Lingerew, M., Derso, A., & Alemu, K. (2020). Does menstrual hygiene management and water, sanitation, and hygiene predict reproductive tract infections among reproductive women in urban areas in Ethiopia? PLoS One, 15(8), e0237696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237696

- Alexander, K. T., Zulaika, G., Nyothach, E., Oduor, C., Mason, L., Obor, D., Eleveld, A., Laserson, K. F., & Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2018). Do water, sanitation and hygiene conditions in primary schools consistently support schoolgirls’ menstrual needs? A longitudinal study in rural western Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081682

- Asumah, M. N., Abubakari, A., Aninanya, G. A., & Salisu, W. J. (2022a). Perceived factors influencing menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls: A qualitative study in the West Gonja Municipality of the Savannah Region, Ghana. Pan African Medical Journal, 41, 146. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2022.41.146.33492

- Asumah, M. N., Abubakari, A., & Gariba, A. (2022b). Schools preparedness for menstrual hygiene management: A descriptive cross-sectional study in the West Gonja Municipality, Savannah Region of Ghana. BMJ Open, 12(4), e056526. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056526

- Behera, M. R., Parida, S., Pradhan, H. S., Priyabadini, S., Dehury, R. K., & Mishra, B. (2022). Household sanitation and menstrual hygiene management among women: Evidence from household survey under Swachh Bharat (Clean India) Mission in rural Odisha, India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 11(3), 1100–1108. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1593_21

- Bernard, H. R., Wutich, A., & Ryan, G. W. (2016). Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Sage Publications.

- Bijani, M., & Hayati, D. (2015). Farmers’ perceptions toward agricultural water conflict: The case of Doroodzan dam irrigation network. Iran Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 17(3), 561–575. http://jast.modares.ac.ir/article-23-10756-en.html

- Bisung, E., & Elliott, S. J. (2016). ‘Everyone is exhausted and frustrated’: Exploring psychosocial impacts of the lack of access to safe water and adequate sanitation in Usoma, Kenya. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 6(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2016.122

- Boazar, M., Yazdanpanah, M., & Abdeshahi, A. (2019). Response to water crisis: How do Iranian farmers think about and intent in relation to switching from rice to less water-dependent crops? Journal of Hydrology, 570, 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.01.021

- Brewis, A., Choudhary, N., & Wutich, A. (2019a). Low water access as a gendered physiological stressor: Blood pressure evidence from Nepal. American Journal of Human Biology, 31(3), e23234. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23234

- Brewis, A., Choudhary, N., & Wutich, A. (2019b). Household water insecurity may influence common mental disorders directly and indirectly through multiple pathways: Evidence from Haiti. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112520

- Brewis, A., Roba, K. T., Wutich, A., Manning, M., & Yousuf, J. (2021). Household water insecurity and psychological distress in Eastern Ethiopia: Unfairness and water sharing as undertheorized factors. SSM – Mental Health, 1, 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100008

- Brewis, A. A., Piperata, B., Thompson, A. L., & Wutich, A. (2020). Localizing resource insecurities: A biocultural perspective on water and wellbeing. WIRES Water, 7(4), e1440. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1440

- Brewis, A., & Wutich, A. (2019). Lazy, crazy, and disgusting: stigma and the undoing of global health. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Brewis, Alexandra, & Wutich, Amber. (2020). A biocultural proposal for integrating evolutionary and political-economic approaches. American Journal of Human Biology, 32(4), e23290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.v32.4

- Brinkley, J., & Niebuhr, N. (2022). Period poverty and life strains: Efforts made to erase stigma and to expand access to menstrual hygiene products. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4042285.

- Cardoso, L. F., Scolese, A. M., Hamidaddin, A., & Gupta, J. (2021). Period poverty and mental health implications among college-aged women in the United States. BMC Women’s Health, 21(14), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01149-5

- Caruso, B. A., Clasen, T., Yount, K. M., Cooper, H. L. F., Hadley, C., & Haardörfer, R. (2017). Assessing women’s negative sanitation experiences and concerns: The development of a novel sanitation insecurity measure. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070755

- Chinyama, J., Chipungu, J., Rudd, C., Mwale, M., Verstraete, L., Sikamo, C., Mutale, W., Chilengi, R., & Sharma, A. (2019). Menstrual hygiene management in rural schools of Zambia: A descriptive study of knowledge, experiences and challenges faced by schoolgirls. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6360-2

- Choudhary, N., Brewis, A., Wutich, A., & Udas, P. B. (2020). Sub-optimal household water access is associated with greater risk of intimate partner violence against women: Evidence from Nepal. Journal of Water and Health, 18(4), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2020.024. PMID: 32833684.

- Collins, S. M., Mbullo Owuor, P., Miller, J. D., Boateng, G. O., Wekesa, P., Onono, M., & Young, S. L. (2019). ‘I know how stressful it is to lack water!’ Exploring the lived experiences of household water insecurity among pregnant and postpartum women in western Kenya. Global Public Health, 14(5), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2018.1521861

- Cooper-Vince, C. E., Arachy, H., Kakuhikire, B., Vořechovská, D., Mushavi, R. C., Baguma, C., McDonough, A. Q., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2018). Water insecurity and gendered risk for depression in rural Uganda: A hotspot analysis. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6043-z

- Cousins, S. (2020). Rethinking period poverty. The Lancet, 395(10227), 857–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30605-X

- Davis, J., Macintyre, A., Odagiri, M., Suriastini, W., Cordova, A., Huggett, C., Agius, P. A., Faiqoh, Budiyani, A. E., Quillet, C., Cronin, A. A., Diah, N. M., Triwahyunto, A., Luchters, S., & Kennedy, E. (2018). Menstrual hygiene management and school absenteeism among adolescent students in Indonesia: Evidence from a cross-sectional school-based survey. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 23(12), 1350–1363. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13159

- du Bray, M., Wutich, A., Larson, K. L., White, D. D., & Brewis, A. (2019). Anger and sadness: Gendered emotional responses to climate threats in four island nations. Cross-Cultural Research, 53(1), 58–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397118759252

- Duignan, S., Moffat, T., & Martin-Hill, D. (2022). Be like the running water: Assessing gendered and age-based water insecurity experiences with Six Nations First Nation. Social Science & Medicine, 298, 114864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114864

- Fialkov, C., Haddad, D., Ajibose, A., Flufy, C. L., Ndungu, M., & Kibuga, R. (2021). The impact of Menstrual Hygiene Management and gender on psychosocial outcomes for adolescent girls in Kenya. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1898424

- Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology & Health, 25(10), 1229–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015

- Friedman, S. R., Williams, L. D., Guarino, H., Mateu-Gelabert, P., Krawczyk, N., Hamilton, L., Walters, S. M., Ezell, J. M., Khan, M., Di Iorio, J., Yang, L. H., & Earnshaw, V. A. (2022). The stigma system: How sociopolitical domination, scapegoating, and stigma shape public health. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1), 385–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22581

- Fukushima, K., Fukushima, N., Sato, H., Yokota, J., & Uchida, K. (2020). Association between nutritional level, menstrual-related symptoms, and mental health in female medical students. PLoS One, 15(7), e0235909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235909

- Gaber, N., Silva, A., Lewis-Patrick, M., Kutil, E., Taylor, D., & Bouier, R. (2021). Water insecurity and psychosocial distress: Case study of the Detroit water shutoffs. Journal of Public Health, 43(4), 839–845. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa157

- Gouvernet, B., Sebbe, F., Chapillon, P., Rezrazi, A., & Brisson, J. (2023). Period poverty and mental health in times of COVID-19 in France. Health Care for Women International, 44(5), 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2022.2070625

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hagaman, A. K., & Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods, 29(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16640447

- Hall, N. L. (2021). From “period poverty” to “period parity” to meet menstrual health needs. Med, 2(5), 469–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.001

- Harris, L., Kleiber, D., Goldin, J., Darkwah, A., & Morinville, C. (2017). Intersections of gender and water: Comparative approaches to everyday gendered negotiations of water access in underserved areas of Accra, Ghana and Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(5), 561–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1150819

- Hennegan, J., Dolan, C., Wu, M., Scott, L., & Montegomery, P. (2016). Measuring the prevalence and impact of poor menstrual hygiene management: A quantitative survey of schoolgirls in rural Uganda. BMJ Open, 6(12), e012596. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012596

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

- Hirve, S., Lele, P., Sundaram, N., Chavan, U., Weiss, M., Steinmann, P., & Juvekar, S. (2015). Psychosocial stress associated with sanitation practices: Experiences of women in a rural community in India. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 5(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2014.110

- Hulland, K. R., Chase, R. P., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Biswal, B., Sahoo, K. C., Panigrahi, P. & Dreibelbis, R. (2015). Sanitation, stress, and life stage: A systematic data collection study among women in Odisha, India. PloS one, 10(11), e0141883, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141883

- Hussein, J., Gobena, T., & Gashaw, T. (2022). The practice of menstrual hygiene management and associated factors among secondary school girls in eastern Ethiopia: The need for water, sanitation, and hygiene support. Women's Health, 18, 174550572210878. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057221087871

- Jalali, R. (2021). The role of water, sanitation, hygiene, and gender norms on women’s health: A conceptual framework. Gendered Perspectives on International Development, 1(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1353/gpi.2021.0001

- Jang, D., & Elfenbein, H. A. (2019). Menstrual cycle effects on mental health outcomes: A meta-analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 23(2), 312–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2018.1430638

- Jensen, P. R. (2018). Undignified dignity: Using humor to manage the stigma of mental illness and homelessness. Communication Quarterly, 66(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2017.1325384

- Krumdieck, N. R., Collins, S. M., Wekesa, P., Mbullo, P., Boateng, G. O., Onono, M., & Young, S. L. (2016). Household water insecurity is associated with a range of negative consequences among pregnant Kenyan women of mixed HIV status. Journal of Water and Health, 14(6), 1028–1031. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2016.079

- Link, B. G, & Phelan, J. (2014). Stigma power. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 24–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.035

- Mason, L., Nyothach, E., Alexander, K., Odhiambo, F. O., Eleveld, A., Vulule, J., Rheingans, R., Laserson, K. F., Mohammed, A., & Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2013). ‘We keep it secret so no one should know’ – A qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural western Kenya. PLoS One, 8(11), e79132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079132

- Maurya, P., Meher, T., & Muhammad, T. (2022). Relationship between depressive symptoms and self-reported menstrual irregularities during adolescence: Evidence from UDAYA, 2016. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 758. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13196-8

- Medina-Perucha, L., Jacques-Aviñó, C., Valls-Llobet, C., Turbau-Valls, R., Pinzón, D., Hernández, L., Briales Canseco, P., López-Jiménez, T., Solana Lizarza, E., Munrós Feliu, J., & Berenguera, A. (2020). Menstrual health and period poverty among young people who menstruate in the Barcelona metropolitan area (Spain): Protocol of a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 10(7), e035914. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035914

- Miiro, G., Rutakumwa, R., Nakiyingi-Miiro, J., Nakuya, K., Musoke, S., Namakula, J., Francis, S., Torondel, B., Gibson, L. J., Ross, D. A., & Weiss, H. A. (2018). Menstrual health and school absenteeism among adolescent girls in Uganda (MENISCUS): A feasibility study. BMC Women's Health, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0502-z

- Ndlovu, E., & Bhala, E. (2016). Menstrual hygiene – A salient hazard in rural schools: A case of Masvingo district of Zimbabwe. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 8(2), 204. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v8i2.204

- Oduor, C., Alexander, K. T., Oruko, K., Nyothach, E., Mason, L., Odhiambo, F. O., Vulule, J., Laserson, K. F., & Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2015). Schoolgirls’ experiences of changing and disposal of menstrual hygiene items and inferences for WASH in schools. Waterlines, 34(4), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.2015.037

- O’Reilly, K., & Dreibelbis, R. (2018). WASH and gender: Understanding gendered consequences and impacts of WASH in/security. In O. Cumming, & T. Slaymaker (Eds.), Equality in water and sanitation services (pp. 80–90). Routledge.

- Pearson, A. L., Mack, E. A., Ross, A., Marcantonio, R., Zimmer, A., Bunting, E. L., Smith, A. C., Miller, J. D., & Evans, T. (2021). Interpersonal conflict over water is associated with household demographics, domains of water insecurity, and regional conflict: Evidence from nine sites across eight Sub-saharan African countries. Water, 13(9), 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13091150

- Pouramin, P., Nagabhatla, N., & Miletto, M. (2020). A systematic review of water and gender interlinkages: Assessing the intersection with health. Frontiers in Water, 2, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.00006

- Radonic, L., & Jacob, C. E. (2021). Examining the cracks in universal water coverage: Women document the burdens of household water insecurity. Water Alternatives, 14(1), 60–78.

- Rosinger, A. Y., Bethancourt, H. J., Young, S. L., & Schultz, A. F. (2021). The embodiment of water insecurity: Injuries and chronic stress in lowland Bolivia. Social Science & Medicine, 291, 114490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114490

- Sivakami, M., Maria van Eijk, A., Thakur, H., Kakade, N., Patil, C., Shinde, S., Surani, N., Bauman, A., Zulaika, G., Kabir, Y., Dobhal, A., Singh, P., Tahiliani, B., Mason, L., Alexander, K. T., Thakkar, M. B., Laserson, K. F., & Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2019). Effect of menstruation on girls and their schooling, and facilitators of menstrual hygiene management in schools: Surveys in government schools in three states in India, 2015. Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 010408. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.010408

- Soeiro, R. E., Rocha, L., Surita, F. G., Bahamondes, L., & Costa, M. L. (2021). Period poverty: Menstrual health hygiene issues among adolescent and young Venezuelan migrant women at the northwestern border of Brazil. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01285-7

- Sommer, M., & Kirk, J. (2008). “Menstruation is on her mind”: Girl-centered, holistic thinking for school sanitation. In WASH in schools notes and news, Volume April (pp. 4–6). UNICEF.

- Stevenson, E. G. J., Greene, L. E., Maes, K. C., Ambelu, A., Tesfaye, Y. A., Rheingans, R., & Hadley, C. (2012). Water insecurity in 3 dimensions: An anthropological perspective on water and women's psychosocial distress in Ethiopia. Social Science & Medicine., 75(2), 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.022

- Sultana, F. (2011). Suffering for water, suffering from water: Emotional geographies of resource access, control and conflict. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 42(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.12.002

- Sumpter, C., & Torondel, B. (2013). A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. PLoS One, 8(4), e62004. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062004

- Tallman, P. S. (2019). Water insecurity and mental health in the Amazon: Economic and ecological drivers of distress. Economic Anthropology, 6(2), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/sea2.12144

- Tegegne, T., & Sisay, M. (2014). Menstrual hygiene management and school absenteeism among female adolescent students in Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1118. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1118

- Tomberge, V. M. J., Bischof, J. S., Meierhofer, R., Shrestha, A., & Inauen, J. (2021). The physical burden of water carrying and women’s psychosocial well-being: Evidence from rural Nepal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7908. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157908

- Torkan, B., Mousavi, M., Dehghani, S., Hajipour, L., Sadeghi, N., Ziaei Rad, M., & Montazeri, A. (2021). The role of water intake in the severity of pain and menstrual distress among females suffering from primary dysmenorrhea: A semi-experimental study. BMC Women's Health, 21(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01184-w

- Trivedi, A. (2018). Women are the secret weapon for better water management, commentary. World Resource Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/women-are-secret-weapon-better-water-management.

- Vashisht, A., Pathak, R., Agarwalla, R., Patavegar, B. N., & Panda, M. (2018). School absenteeism during menstruation amongst adolescent girls in Delhi, India. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 25(3), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_161_17

- Veisi, K., Bijani, M., & Abbasi, E. (2020). A human ecological analysis of water conflict in rural areas: Evidence from Iran. Global Ecology and Conservation, 23, e01050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01050

- Vora, S. (2020). The realities of period poverty: How homelessness shapes women’s lived experiences of menstruation. In C. Bobel, I. T. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling, & T. A. Roberts (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies (pp. 31–47). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Walters, V. (2014). Urban homelessness and the right to water and sanitation: Experiences from India’s cities. Water Policy, 16(4), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2014.164

- Watts S. (2004). women, water management and health. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(11), 2025–2026. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1011.040237

- White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., Grellier, J., Economou, T., Bell, S., Bratman, G. N., Cirach, M., Gascon, M., Lima, M. L., Lõhmus, M., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Ojala, A., Roiko, A., Schultz, P. W., van den Bosch, M., & Fleming, L. E. (2021). Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 8903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87675-0

- Workman, C. L., Brewis, A., Wutich, A., Young, S., Stoler, J., & Kearns, J. (2021). Understanding biopsychosocial health outcomes of syndemic water and food insecurity: Applications for global health. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 104(1), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0513

- Workman, C. L., & Ureksoy, H. (2017). Water insecurity in a syndemic context: Understanding the psycho-emotional stress of water insecurity in Lesotho, Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 179, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.026

- Wutich, A., Beresford, M., SturtzSreetharan, C., Brewis, A., Trainer, S., & Hardin, J. (2021). Metatheme Analysis: A qualitative method for cross-cultural research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211019907

- Wutich, A., & Brewis, A. (2014). Food, water, and scarcity: Toward a broader anthropology of resource insecurity. Current Anthropology, 55(4), 444–468. https://doi.org/10.1086/677311

- Wutich, A., & Brewis, A. (2019). Data collection in cross-cultural ethnographic research. Field Methods, 31(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X19837397

- Wutich, A., Brewis, A., & Tsai, A. (2020). Water and mental health. WIRES Water, 7(5), e1461. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1461

- Wutich, A., Jepson, W., Velasco, C., Roque, A., Gu, Z., Hanemann, M., Hossain, M. J., Landes, L., Larson, R., Li, W. W., Morales-Pate, O., Patwoary, N., Porter, S., Tsai, Y., Zhenge, M., & Westerhoff, P. (2022). Water insecurity in the Global North: A review of experiences in U.S. colonias communities along the Mexico border. WIRES Water, 9(4), https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1595

- Wutich, A., & Ragsdale, K. (2008). Water insecurity and emotional distress: Coping with supply, access, and seasonal variability of water in a Bolivian squatter settlement. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2116–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.042

- Wutich, A., Rosinger, A., Brewis, A., Beresford, M., & Young, S. (2022). Water sharing is a distressing form of reciprocity: Shame, upset, anger, and conflict over water in twenty cross-cultural sites. American Anthropologist, 124(2), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13682

- Yaliwal, R. G., Biradar, A. M., Kori, S. S., Mudanur, S. R., Pujeri, S. U., & Shannawaz, M. (2020). Menstrual morbidities, menstrual hygiene, cultural practices during menstruation, and WASH practices at schools in adolescent girls of North Karnataka, India: A cross-sectional prospective study. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2020, 6238193. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6238193

- Yilmaz, S. K., Bohara, A. K., & Thapa, S. (2021). The stressor in adolescence of menstruation: Coping strategies, emotional stress & impacts on school absences among young women in Nepal. International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178894