?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Objective

To identify strategies and develop a strategic action plan to enhance accessibility to healthcare in rural areas of Zimbabwe.

Methods

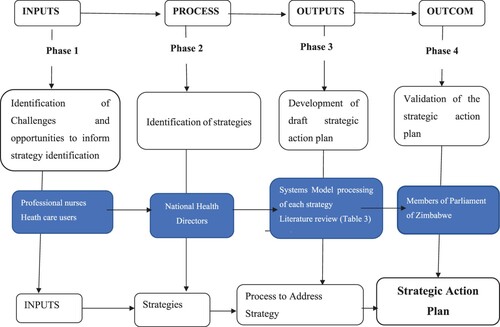

A cross sectional research approach with four (4) phases. Phase one (1) (quantitative), data was collected from professional nurses using self-administered questionnaires, healthcare users using interview questionnaires. Phase two (2) (qualitative), information was collected from a nominal group of national health directors leading to development strategic action plan in Phase three (3) informed by Phases 1 and 2, systems model and literature control. Strategic action plan was finalised and validated by members of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health in Phase 4.

Settings

Two districts (Masvingo and Chegutu) in two provinces (Masvingo and Mashonaland West) were involved.

Participants

Conveniently sampled professional nurses (90) and healthcare users (445) using the sampled public health facilities (Phase 1); conveniently sampled national health coordinators (five) (Phase 2); and all five members of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health (Phase 4).

Research findings

The strategic action plan focused on improving the health infrastructure; providing medical drugs, health workers and medical equipment; addressing shortages; and improving the capacity of the healthcare system.

Conclusion

Active participation at all levels (professional nurses, healthcare users, national health directors and members of parliament) allowed the development of a strategic action plan.

Introduction

Improved health and wellbeing are the goals of every healthcare delivery system in the world (Azétsop & Ochieng, Citation2015). Citizens in every country, including Zimbabwe, have a right to healthcare. Allocating resources in a fair manner ensures that citizens can access healthcare, essential medical drugs, skilled and adequate healthcare workers, and health facilities (Chandler et al., Citation2013). However, many rural and remote communities worldwide often experience high levels of inaccessibility of healthcare (Dowhaniuk, Citation2021). According to a World Health Organisation (WHO) report (Citation2017), half of the global population cannot access essential health care. Even within the developed world, equitable and accessible healthcare is difficult to achieve, particularly in rural populations where accessibility to quality healthcare can be dictated by the socio-economic status of families (WHO, Citation2015a). In Zimbabwe, according to the census from 2012 (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZNSA), Citation2012a) 67.8% of the population live in rural areas. According to the census from 2012, approximately 7 million Zimbabweans (54%) lack access to healthcare. Eighty-three (83%) percent of those 7 million people live in rural areas where professional nurse coverage is merely 38% of the nursing workforce (ZNSA, Citation2012b; Ministry of Health and Child Welfare (MoHCC), Citation2014).

Some of the health facilities had to close due to this shortage of professional nurses. The congestion at the few functioning health facilities contributes to long waiting times, delayed diagnosis (Kamvura et al., Citation2022) and increasing mortality rates that could have been prevented (Nyandoro et al., Citation2016). Alarmingly, it was found that 61% of mothers in rural areas fail to take their sick children to the health facilities ZNSA (Citation2015). Forty-five (45%) percent of pregnant women delivering in rural areas are assisted by untrained health workers and 32% deliver at home (ZNSA, Citation2015). The unavailability of midwives may be related to midwives resigning from health facilities in rural areas to move to urban areas with improved working conditions. Some take on part-time work for an additional income and others emigrate.

According to the WHO (Citation2015), the distance to the nearest health facility should not be more than 5 km to enhance access to healthcare. In Zimbabwe, people in rural areas walk more than 10 km and some travel up to 50 km to the nearest health facility (Loewenson et al., Citation2014).

The contribution of household and individual expenditure on health has increased from 45.8% in 2010 to 67% in 2015 (Buzuzi et al., Citation2016). This has led to limited access to healthcare for those who can afford it and has exposed the poor to increasingly high costs, resulting in them consulting traditional healthcare services (WHO & World Bank, Citation2015).

The shortage of medical drugs, vaccines and healthcare workers (Kamvura et al., Citation2022), as well as transport problems, affected community outreach programmes like the immunisation of children under five. Community outreach programmes were cancelled (Mhere, Citation2013). In respect of health financing, Zimbabwe’s healthcare system has been deeply affected. Every fiscal year, Zimbabwe fails to allocate the minimum 15% of its annual budget to health as indicated in the Abuja Declaration of 2001, where African leaders had agreed to allocate 15% of their countries’ total fiscal budget to the health sector (Loewenson et al., Citation2014). The annual budget statement of November 2022 by the Minister of Finance and Economic Development in his presentation of the year 2023 fiscal budget allocated 11% of Zimbabwe’s annual fiscal budget (Ministry of Finance, Citation2022). In his presentation, the Minister acknowledged the financial constraints in the health sector that have contributed to failing to arrest human resources shortages and brain drain and providing adequate essential drugs. This might be due to a lack of strategic action planning. In a study conducted in Zimbabwe on barriers to provision of non-communicable disease care, it was found that medication was in short supply in all sampled clinics thus affecting healthcare delivery and personally affecting collective nurses’ feeling of helplessness (Kamvura et al., Citation2022).

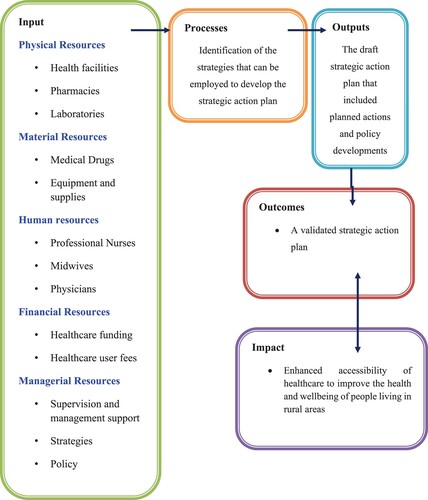

A strategic action plan is, in essence, a road map designed to lead to a required potential, such as the accomplishment of a goal or resolution of a problem (Ahmed et al., Citation2014). The strategic action plan in this research study was also defined as a set of established actions or interventions by stakeholders to enhance access to healthcare in the rural areas of Zimbabwe. These stakeholders include members of parliament, national health directors, the Ministry of Health and Child Care, the Ministry of Higher Education and Technology, the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. Strategic action planning assists to identify specific and measurable short-term, mid-term and long-term actions, with appropriate milestones and outcomes that organisations will take to meet each priority strategy (Rajan et al., Citation2014). The strategic action plan, as presented in , illustrates the measures and actions needed to address lack of health infrastructure and shortages of medical drugs, health workers and financial resources, so as to improve the accessibility of healthcare services.

The objective of the study was to develop a strategic action plan to enhance access to healthcare in the rural areas of Zimbabwe. The systems model () was applied to strengthen the effectiveness of healthcare systems (Rajan et al., Citation2014) and all the systems model components were considered during the development of the strategic action plan. The components of the systems model include inputs, processes, outputs and outcome. The healthcare service provision depends on the way inputs such as physical, human, material, financial and managerial resources were processed to produce desirable outputs which can contribute to favourable health outcomes (MacKinney et al., Citation2014). The Systems Model made it easier to link the quantitative and qualitative research methods in the different phases of the study. Quantitative research was used for collecting data on the Systems Model inputs, while qualitative research was used during the process of developing outputs and outcomes. Data collection using Systems Model processes was sequential that is quantitative to qualitative research methods.

Figure 1. Systems Model : as applied in the development of a validated strategic action plan to enhance accessibility to healthcare in rural areas.

Inputs refer to human, material, physical, financial and managerial resources that were utilised to produce the outputs of a healthcare system (Hayes et al., Citation2011). Processes indicate strategic actions used for the development of strategies that direct policy development to enhance the accessibility of health care. Hayes et al. (Citation2011) and Van Olmen et al. (Citation2012) highlighted that outputs include the results from the planned activities while the outcome is the association between the output and processes followed and reflects the progress in achieving the objectives.

The systems model inputs (human, material, physical, financial and managerial) were reviewed and taken into consideration in the findings in Phase 1 (professional nurses and healthcare users), during which the challenges and opportunities with regard to the accessibility of healthcare in rural areas in Zimbabwe were investigated. The processes in this study, according to the systems model (), were the steps that were taken to bring about the preferred outputs that was the draft strategic action plan during Phase 3 from findings from Phase 1 and 2. The important outcome was the validated strategic action plan that reflected the inputs, process, output and the outcome.

Methods

A multiple-methods research design was followed during data collection. A quantitative approach was followed during phase one (1) and a qualitative approach during phases two (2) to four (4). The research topic was a step-by-step process of using quantitative and qualitative methods that were sequentially followed, with each new method building on what was collected previously to address the research objectives (Johnson, Citation2015). The use of quantitative approach in phase one (1) and qualitative approach in phase two (2), three (3) and four (4) was to enhance validity (Johnson, Citation2015; Polit & Beck, Citation2014).

The research was conducted based on the ethical principles of Helsinki (World Medical AssosiationCitation2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Studies Higher Degrees Committee, College of Human Sciences at the Higher Educational Institution, reference number HSHDC 240/2013 as well as the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/1832). Written consent was obtained from all participants before data collection commenced.

The study was organised in four phases ().

Figure 2. Illustrative diagram of the process of developing the strategic action plan using the Systems Model.

In Phase one (1), a quantitative approach was taken to identify the challenges and opportunities inherent in healthcare accessibility in the rural areas of Zimbabwe. The data was gleaned from a sample of ninety (90) professional nurses (PN) and four hundred and forty-five (445) healthcare users (HCU), segregated as in (demographics). The PN population working in Masvingo and Chegutu districts was one hundred and twenty (120) mainly at rural public health facilities during the time of data collection, as per Zimbabwe Health Services Board (ZNSA and ICF International, Citation2016). Convenience sampling was used and all available PNs during the time of data collection, working in public health facilities (PHFs) in Masvingo and Chegutu Districts who were willing to participate were included.

Table 1. Frequency distribution: Demographic characteristics of the study respondents.

The population living in the rural areas of Masvingo district (211,732 people) and Chegutu district (149,025 people) were the target population (ZNSA, Citation2012a). Sample size for HCUs was determined with the assistance of a statistician based on Dobson's formula for descriptive studies, (Dobson et al., Citation1991).

The researcher selected this formula to calculate the sample as the study population was above 50,000 (population above 50,000 is regarded as infinite) (Godden, Citation2004). Convenience sampling was used due to the nature of the settlements which are scattered (villages, farms and resettlements). There were challenges in conducting systematic sampling in a scattered settlement especially long distances between households (Aune-Lundberg & Strand, Citation2014).

In Phase 1, quantitative data was obtained using self-administered questionnaires, for PNs and structured interviews, using a questionnaire to collect data from HCUs. The questionnaires were developed after a thorough literature review taking into consideration the inputs and the steps needed, according to the systems model for accessible healthcare and service provision. Data that was collected through self-administered questionnaires with PNs and structured interview questionnaires with HCUs (quantitative data) were collated and entered into Census and Survey Processing System (CSPro) Version 4 and exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 for analysis. Confidentiality was ensured through the anonymity of the respondents.

Phase 2 utilised a qualitative method to identify strategies using the nominal group technique (NGT). The population in Phase 2 were fifteen (15) national health directors of the Ministry of Health and Child Care. Convenient sampling was done since all willing and available national health directors were invited to participate in the nominal group and ultimately five national health directors participated. Data was collected through the nominal group technique. A Nominal group technique is a group process for gathering opinions, aggregating judgments and reaching consensus to increase rationality and creativity (McMillan et al., Citation2014). The nominal group process permitted in-depth exploration and eliciting of information from the stakeholders permitting a quick development of a list of consensual and ranked answers to a precise question, in this study ninety (90) minutes were taken to reach consensus by five participants (Fournier et al., Citation2014). Participants were directly involved in both data collection and analysis, thereby minimising researcher-bias (Hiligsmann et al., Citation2013). The process was guided by the systems model as theoretical framework (Mangundu, Citation2018). Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by using numbers instead of names of the participants to conceal the identity of a participant from being linked to the data.

The identified strategies were aligned with the systems model inputs (resources) (), defining the processes, actions and methods needed to address each strategy and determine outcomes that could be used to develop the strategic action plan. A literature control was conducted to support or contradict the findings from the nominal group. Based on the strategies developed by the nominal group participants and literature control, the researcher consolidated the strategies into a draft strategic action plan in Phase 3 for further analysis and validation in Phase 4.

Table 2. Systems Model illustration for each resource (Inputs) strategy development.

The population in Phase 4 were members of parliament of Zimbabwe for the purposes of bringing the policy dimension to the whole process by eliciting, soliciting opinions and priorities from policy makers. The sample was conveniently selected, as all members of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health (PPCH) who were willing and available were invited. All five members of the PPCH volunteered to participate. The validation process involved five steps (). During the first step, the draft strategic action plan was presented for review. It was then amended during the second step, whereupon participants reached consensus on the strategies to be included or excluded in the draft strategic action plan during the third step. All comments were discussed to ensure that every participant had an equal voice and that the comments were incorporated, allowing the researcher to put in place the strategic action plan for validation in fourth step. In the fifth step, the strategic action plan was shared with all five validation participants through emails for approval during a virtual (electronic) meeting, to ensure that all the participants were satisfied and validated the final strategic action plan (). Confidentiality was ensured by using numbers instead of names of the participants (Participant #1) to ensure the data was not linked to the identity of the participants.

Table 3. Strategies voted according to priorities.

Results

Phase 1 results

There was evidence in Phase 1 of challenges associated with accessibility to health care in rural areas of Zimbabwe. Professional nurses (PNs) [61 out of 90 (67.77%; f = 61) PNs] and HCUs [293 out of 445 (65.84%; f = 293)] opined that lack of infrastructure development was contributing to challenges in travelling long distances by walking as the preferred means of travelling to the nearest health facility. The challenges related to travelling long distances were worsened by lack of transport [270 out of 417 (64.74%; f = 270) HCUs] that included unavailability of ambulances at the rural health facilities [403 out of 443 (90.97%; f = 403) HCUs].

Medical drugs were one of the important material resources input to accessibility to health care but were rarely available at rural health facilities as reported by PNs [50 out of 90 (55.55%; f = 50)] and HCUs [249 out of 445 (55.95%; f = 249)]. The lack of consistency in supplying medical drugs might be the reason for HCUs [249 out of 445 (55.95%; f = 249)] failing to obtain medical drugs during their visits to the health facility despite obtaining prescriptions.

HCUs face challenges of accessibility to PNs [13 out of 90 (14.44%; f = 13) PNs and 134 out of 445 (30.11%; f = 134) HCUs] especially at the rural health facilities manned by 1 PN [5 out of 90 (5.55%; f = 5) PNs and 31 out of 445 (6.96%; f = 31) HCUs]. There was evidence of shortage of PNs as 3 PNs manning a health facility covering a population of 2732 was way below the recommended ratio of 2.84 PNs to 1000 population. No physicians were employed in the rural health facilities and no PN had a nursing degree [20 out of 90 (22.22%; f = 20) PNs] the reason why HCUs [284 out of 445 (63.82%; f = 284] were dissatisfied with the health care system in the rural areas.

Despite challenges of financial resources, HCUs had to bring their medical supplies, beyond their capacity as the average income of HCUs [133 out of 311 (42.76%; f = 133)] was less than US$100. The HCUs [339 out of 445 (76.1%; f = 339)] could not afford to pay health care users fees at rural health facilities and district hospitals, this has been worsened by the lack of medical insurance.

Phase 2 results

Results from phase 1 were used to inform data analysis in phase 2 using nominal group technique. The nominal group generated 19 ideas from the results from phase 1, which were grouped into 13 themes after merging similar ideas and the participants then individually ranked the top 5 themes according to priority, producing five strategies as in . The voted strategies were rearranged according to the priority with the highest score as first priority followed by the rest. As indicated in , when scores were tied, both strategies received the same ranking and priority. The agreed-upon priority strategies were discussed, elaborated on or contradicted by means of a literature control in Phase 3, producing a draft strategic action plan which was presented in phase 4 for review, validation and approval.

Phase 4 results

A total of six validated and approved strategies were retained (). The approved and agreed strategies for enhancing the accessibility of healthcare in the rural areas of Zimbabwe were to (1) develop health infrastructures in the rural areas; (2) provide medical drugs at the rural health facilities; (3) develop and retain human resources (health workers) at the rural health facilities; (4) review the workload of health workers at the health facilities and address shortages; (5) provide adequate material resources at the rural health facilities; and (6) improve the capacity of the healthcare delivery and management systems. The five participants involved in the validation agreed to the final strategic action plan as presented in .

Table 4. Validated, approved and agreed Strategic Action Plan (actions are included in the text).

Discussion of findings

Strategic action planning was seen as a process of bringing together ideas and resources to strengthen procedures and operations, ensuring that health workers and other stakeholders were focused on common goals and that a target was set (Sadeghifar et al., Citation2015). The strategic action plan was the result of a thorough consultative process, as all important stakeholders – professional nurses and healthcare users (Phase 1), national health directors (Phase 2) and members of parliament (Phase 4) – were actively involved during the development thereof. The process applied by the researcher was in line with the accepted strategic action planning procedure. The researcher conducted a literature control for every strategy, which was then thoroughly discussed during validation. The researcher applied the systems model as theoretical framework (), using its components to develop the strategies. The components of the systems model (Mangundu, Citation2018) are inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes. Thus, in developing the draft strategic action plan, the strategies were analysed and formulated, aligning each strategy with its systems model component. The first strategy in the strategic action plan was to develop health infrastructure ().

Developing health infrastructure in rural areas

All healthcare services depend on the existence of a basic health infrastructure, and this has been described as critical to the healthcare delivery system (Smith et al., Citation2015). This was agreed by the participants who identified the strategy and those who validated the strategic action plan. They maintained that the development of health infrastructure is essential and that health facilities should be built within five (5) kilometres walking distance in villages, while existing health facilities should be maintained and rehabilitated. The findings were consistent with a study done in Uganda by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation (IHME), Citation2014) that evaluated the Ugandan healthcare system, which found that the utilisation of healthcare facilities improved when healthcare users had to travel smaller distances. Health infrastructure provides communities and the nation with the ability to prevent and control disease, promote public health, and prepare and act against disease outbreaks and chronic (ongoing) challenges related to the health of citizens (World Bank, Citation2016). As a result, the members of parliament (i.e. the participants validating the strategic action plan) indicated a willingness to take the responsibility of tabling a motion in parliament to prioritise building health facilities in villages that lack health infrastructure and also prioritise the supply of medical drugs at rural health facilities.

Provision of medical drugs to rural health facilities

Medical drugs shortages are a global concern and especially prevalent in low-income countries (Ndzamela & Burton, Citation2020). One of the challenges related to medicine shortfalls included inconsistent or short supply at rural health facilities (Mkoka et al., Citation2014). Other challenges highlighted by Ndzamela and Burton (Citation2020) in the South African context, include staff shortages, administrative errors, and insufficient funds. A study done by Kamvura et al. (Citation2022) in Zimbabwe indicated that the shortage of medication had a negative effect on the morale of the nurses and is detrimental to the health of the patients. According to the systems model, medicines are an important part of the material resources input. Because of this, the action was recommended to establish partnerships with national and international medical drug producers and non-government organisations and to introduce health levies and local taxes for the procurement of medical drugs in order to facilitate a constant medicine supply pipeline. The findings are similar to a study in Zimbabwe by Jamison et al. (Citation2013), who suggested that medical drug supply in rural health facilities was a challenge that could be addressed through partnerships between the government, private companies, national and international drug producers, and non-government organisations in Zimbabwe. The national health directors suggested the same, after recognising that a lack of sufficient funding for medical drugs from the central government was deterring expectations of improved medical drug availability in rural health facilities. This method has also worked well in India, as reported in a study conducted by Sharma and Chaudhury (Citation2015) on improving the availability and accessibility of medicines in India. The major factor contributing to the shortage of medical drugs in Zimbabwe was the lack of health workers who had experience in ordering the medicines, and this might have contributed to the national health directors proposing to capacity-build professional nurses on logistics management, focusing on ordering and managing medical drugs at health facilities (Mangundu, Citation2018). This also facilitates the development and retention of human resources.

Development and retention of human resources in rural health facilities

Human resources form an essential part of the inputs (systems model) required to enhance the accessibility of healthcare (Mkoka et al., Citation2014). Human resources management is the organisational role that regulates issues associated with employees. It includes recruitment, performance management, organisational development, remuneration, employee motivation, and training (Nyandoro et al., Citation2016). The strategy on the development and retention of human resources aimed to address critical shortages of health workers, especially professional nurses, who are key providers of healthcare services in rural areas. As a result, the introduction of incentives like transport and hardship allowances and promoting the career growth of health workers were recommended as actions for retaining the skills in rural health facilities. The study’s findings are similar to those of a study in Tanzania by Mkoka et al. (Citation2014) who propounded that offering opportunities for career growth (advancement) to health workers to improve their competencies and skills contributed to their retention. When health workers are trained, adequately skilled and retained at their respective health facilities, access to health services will be enhanced. In a study in Zimbabwe by Nyandoro et al. (Citation2016), the findings indicated that incentives like rural transport and hardship and housing allowances assisted in addressing staff shortages in rural areas. Of particular importance, as noted by professional nurses, is the workload versus the number of health workers. Thus, a review of the workload at rural health facilities is crucial.

Reviewing the workload of health workers at health facilities and addressing shortages

Human resources are inequitably distributed between urban and rural areas and between primary, secondary and tertiary levels of care (Bonfim et al., Citation2016). There are legitimate concerns about balancing the workload and shortages in human resources in health service delivery. Hence, participants agreed to conduct a workload/staff-need assessment in Zimbabwe. Workloads and shortages can be determined by means of the Workload Indicator for Staff Needs (WISN). Govule et al. (Citation2015) describe WISN as a method that calculates the number of health workers based on health facility workload. It uses a form of activity analysis (activity standards), together with measures of utilisation and workload to determine staffing requirements. A study conducted in Namibia by McQuide et al. (Citation2013) who applied the WISN, found that the country’s health facilities had appropriate numbers of professional nurses. However, the nurses were very inequitably distributed between the different types of health facilities, with the total professional nurse workforce in Namibia skewed towards hospitals. This type of inequitable distribution could also be the case in Zimbabwe, as some health facilities had four professional nurses while others were manned by only two nurses. In addition to conducting the WISN, it was important to assess the availability of material resources, including medical equipment at the health facilities, as the provision of adequate material resources is essential.

Provision of adequate material resources to the health facilities

This strategy aims to improve service delivery to an ever-increasing population with limited or reducing material resources. Hence action was recommended with regard to the procurement and delivery of basic medical equipment (according to the WHO’s standard list) to rural health facilities with or without shortages. The findings of this study in respect of material resources agree with the findings of a study done in South America by Bonfim et al. (Citation2016). Kamvura et al. (Citation2022) highlighted that the shortage of equipment is a barrier in service delivery. Equipment and medical supplies form an essential part of service delivery at rural health facilities and contribute to improvement in the capacity of the healthcare delivery system.

Improving the capacity of the healthcare delivery and management systems

The healthcare system functions when financial resources are available to pay salaries, medical drugs, ambulance operations, and other logistics expenditure (Asante et al., Citation2016). The strategy in this study focused on improving the capacity of healthcare delivery and management systems.

According to researchers in Tanzania, financial resources are required to finance healthcare systems, including healthcare assets and finances which form an integral part of the inputs (systems model) needed to provide access to healthcare (Mkoka et al., Citation2014). The availability of financial resources influences service delivery. In order to strengthen healthcare systems, multi-year funding systems for paying medical drugs, equipment, salaries and allowances are needed (Mangundu, Citation2018). The financial policies should include funding mechanisms like performance-based health facility grants that ensure the sustainable provision of essential materials and health workers. Strengthening the harmonisation and co-ordination of all the systems model inputs into all health programmes is essential to improve the capacity of the healthcare delivery system. The members of parliament, together with the national directors, recommended an action to align the health regulations, statutory instruments, and health policies with the new constitution to improve policies that enhance accessibility to healthcare in rural areas. The other action they agreed on was to provide training on leadership and financial and resource management to health workers at rural health facilities, in order to translate knowledge into policy and practice, as suggested by research evidence.

Conclusion

The study contributed to the development of a strategic action plan where all important stakeholders – professional nurses, healthcare users, national health directors, and members of parliament of Zimbabwe – were actively involved. Involvement of all of these levels (Ministry of Health and policy makers) to develop and validate the strategic action plan, might enhance its implementation. The accessibility of healthcare in rural areas is vital to healthcare users and health workers, and it is also in the interest of politicians and the country to enhance service delivery and health-related outcomes.

The members of parliament have agreed to conduct an assessment of the conditions of the health facilities’ infrastructure, as a starting point, and this should pave the way to enforcing the strategic action plan in line with the infrastructural development policy.

The study led to the development of a strategic action plan in line with the application of the systems model, incorporating the necessary inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes to enhance access to healthcare services in rural areas. The strategic action plan highlighted the need for the mobilisation of financial resources to make medical drugs available, to attract and retain senior managers and professional nurses, to provide the required medical equipment and to ensure health infrastructure maintenance, as well as to build health facilities that are accessible to the community.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support of Prof. Roets L and Prof. Elsie Janse van Rensburg for their guidance, assistance, and reviews during the writing of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahmed, A., Bwisa, H., Otieno, R., & Karanja, K. (2014). Strategic decision making: Process, models, and theories. Journal of Business Management and Strategy, 5, 78-104. https://doi.org/10.5296/bms.v5i1.5267

- Asante, A., Price, J., Hayen, A., Jan, S., & Wiseman, V. (2016). Equity in healthcare financing in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of evidence from studies using benefit and financing incidence analyses. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0152866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152866

- Aune-Lundberg, L., & Strand, G. H. (2014). Comparison of variance estimation methods for use with two-dimensional systematic sampling of land use/land cover data. Environmental Modelling & Software, 61, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.07.001

- Azétsop, J., & Ochieng, M. (2015). The right to health, health systems development and public health policy challenges in Chad. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 10(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13010-015-0023-z

- Bonfim, D., Laus, A. M., Leal, A. E., Fugulin, F. M. T., & Gaidzinski, R. R. (2016). Application of the workload indicators of staffing need method to predict nursing human resources at a Family Health Service. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 24, e2683. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1010.2683

- Buzuzi, S., Chandiwana, B., Munyati, S., Chirwa, Y., Mashange, W., Chandiwana, P., Fustukian, S., & McPake, B. (2016). Impact of user fees on the household economy in Zimbabwe. ReBUILD RPC Working Paper,15. www.rebuildconsortium.com.

- Chandler, I. R., Kizito, J., Taaka, L., Nabirye, C., Kayendeke, C., DiLiberto, D., & Staedke, S. G. (2013). Aspirations for quality healthcare in Uganda: How do we get there? Human Resources for Health, 11(13), 1. http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/13.

- Dobson, A. J., Kuulasmaa, K., Eberle, E., & Scherer, J. (1991). Confidence intervals for weighted sums of poison parameters. Statmed, 10(3), 457–462. https://doi:1002/sim.4780100317.

- Dowhaniuk, M. (2021). Exploring country-wide equitable government health care facility access in Uganda. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01371-5

- Fournier, J. P., Escourrou, B., Dupouy, J., Bismuth, M., Birebent, J., Simmons, R., Poutrain, J. C., & Oustric, S. (2014). Identifying competencies required for medication prescribing for general practice residents: a nominal group technique study. BioMedical Centre Family Practice, 15(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-139

- Godden, W. (2004). Sample size formulas. Available from: http://williamgodden.com/samplesizeformula.pdf. (Accessed April 7, 2023).

- Govule, P., Mugisha, J. F., Katongole, S. P., Maniple, E., Nanyingi, M., & Onzima, R. A. D. (2015). Application of workload indicators of staffing needs (WISN) in determining health workers requirements for mityana general hospital, Uganda. International Journal of Public Health Research, 3(5), 254–263. http://www.openscienceonline.com/journal/ijphr).

- Hayes, H., Parchman, M. L., & Howard, R. (2011). A logic model framework for evaluation and planning in a primary care practice-based research network (PBRN). The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 24(5), 576–582. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110043

- Hiligsmann, M., Salas, M., Hughes, D. A., Manias, E., Gwadry-Sridhar, F. H., Linck, P., & Cowell, W. (2013). Interventions to improve osteoporosis medication adherence and persistence: a systematic review and literature appraisal by the ISPOR Medication Adherence & Persistence Special Interest Group. Osteoporosis International, 24(12), 2907–2918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2364-z

- Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation (IHME). (2014). Health service provision in Uganda: Assessing facility capacity, costs of care, and patient perspectives. IHME.

- Jamison, D. T., Summers, L. H., Alleyne, G., Arrow, K. J., Berkley, S., Binagwaho, A., Bustreo, F., Evans, D., Feachem, R. G. A., Frenk, J., Ghosh, G., Goldie, S. J., Guo, Y., Gupta, S., Horton, R., Kruk, M. E., Mahmoud, A., Mohohlo, L. K., Ncube, M., … Yamey, G. (2013). Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. The Lancet, 382(9908), 1898–1955. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4

- Johnson, J. S. (2015). Broadening the application of mixed methods in sales research. Journal of Persona; Selling & Sales Management, 35(4), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2015.1016953

- Kamvura, T. T., Dambi, J. M., Chiriser, E., Turner, J., Verhey, R., & Chibanda, D. (2022). Barriers to the provision of non-communicable disease care in Zimbabwe: a qualitative study of primary health care nurses. BMC Nursing, 21(64), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-00841-1

- Loewenson, R., Masotya, M., Mhlanga, G., & Manangazira, P. (2014). Assessing Progress towards Equity in Health Zimbabwe. Training and Research Support Centre and Ministry of Health and Child Care, Zimbabwe, in the Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET).

- MacKinney, A. C., Mueller, K. J., Vaughn, T., & Zhu, X. (2014). From health care volume to health care value-success strategies for rural health care providers. Journal of Rural Health, 30(2), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12047

- Mangundu, M. (2018). Strategies to enhance accessibility to healthcare in rural areas of Zimbabwe. UNISA.

- McMillan, S. S., Kelly, F., Sav, A., King, M. A., Whitty, J. A., & Wheeler, A. J. (2014). Australian community pharmacy services: A survey of what people with chronic conditions and their carers use versus what they consider important. Health Services Research. BMJ Open, 4, e006587. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006587. Accessed April, 7 2023.

- McQuide, P. A., Kolehmainen-Aitken, R., & Forster, N. (2013). Applying the workload indicators of staffing need (WISN) method in Namibia: challenges and implications for human resources for health policy. Human Resources for Health, 11(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-64

- Mhere, F. (2013). Health insurance determinants in Zimbabwe: Case of Gweru Urban. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 14(2), 62–79.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. (2022). The 2023 National Budget Statement. 24 November 2022. Harare. Zimbabwe.

- Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. (2014). The national health strategy for Zimbabwe 2014-2018. Equity and quality in health: A people’s right. Government Printers.

- Mkoka, D. A., Goicolea, I., Kiwara, A., Mwangu, M., & Hurtig, A. K. (2014). Availability of drugs and medical supplies for emergency obstetric care: experience of health facility managers in a rural District of Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-108

- Ndzamela, S., & Burton, S. (2020). Patients and healthcare professionals’ experiences of medicine stock-outs and shortages at a community healthcare centre in the Eastern Cape. South African Pharmaceutical Journal, 87(5), 37i–37 m. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-mp_sapj-v87-n5-a10.

- Nyandoro, Z. F., Masanga, G. G., Munyoro, G., & Muchopa, P. (2016). Retention of health workers in rural hospitals in Zimbabwe: A case study of makonde district, mashonaland west province. International Journal of Research in Business Management, 4(6), 27–40.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2014). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice (8th Edition). Lippincott Williams, & Wilkins.

- Rajan, D., Kalambay, H., Mossoko, M., Kwete, D., Bulakali, J., Lokonga, J. P., Porignon, D., & Schmets, G. (2014). Health service planning contributes to policy dialogue around strengthening district health systems: an example from DR Congo 2008–2013. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 522. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0522-4

- Sadeghifar, J., Jafari, M., Tofighi, S., Ravaghi, H., & Maleki, M. R. (2015). Strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation processes in hospital systems: A survey from Iran. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(2), 57. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n2p56

- Sharma, S., & Chaudhury, R. R. (2015). Improving availability and accessibility of medicines: A tool for increasing healthcare coverage. MedPub Journals, 7(5), 12. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/Improving-Avialability-of-ATool-Sharma-Chaudhury/f90120ad8b600d07c826914fa9d1c9642a430c02.

- Smith, D., Roche, E., O’Loughlin, K., Brennan, D., Madigan, K., Lyne, J., Feeney, L., & O’Donoghue, B. (2015). Satisfaction with services following voluntary and involuntary admission. Journal of Mental Health, 23(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2013.841864

- Van Olmen, J., Criel, B., Bhojani, U., Marchal, B., van Belle, S., Chenge, M. F., Hoerée, T., Pirard, M., Van Damme, W., & Kegels, G. (2012). The Health System Dynamics Framework: The introduction of an analytical model for health system analysis and its application to two case-studies. Health, Culture and Society, 2(1). https://doi:10.5195/hcs.2012.71.

- WHO & World Bank. (2015). Tracking Universal Health Coverage, First Global Monitoring Report. Geneva, Switzerland. https://ifa.ngo>health.

- World Bank. (2016). Changing Growth Patterns, Improving health outcomes. Harare, Zimbabwe. https://documents.worldbank.org.

- World Health Organisation. (2015). Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. https://apps.who.int.

- World Health Organisation. (2017). World Bank and WHO: Half the world lacks access to essential health services, 100 million still pushed into extreme poverty because of health expenses. http://Who.int/news/item/13-12-2017-world-bank-and-who-half-the-world-lacks-access-to-essential-health-services-100-million-still-pushed-into-extreme-poverty-because-of-health-expenses.

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, E1–E4. http://jama.jamanetwork.com.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2012a). Census Final Report 2012. ZIMSTAT. Harare, Zimbabwe.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2012b). Zimbabwe Demographic Health Survey 2010-11. Harare: ZIMSTAT. https://www.zimstat.co.zw.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2015). Zimbabwe Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014, Final Report. Harare, Zimbabwe. https://www.zimstat.co.zw.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency & ICF International. (2016). Zimbabwe demographic and health survey of 2015: Key indicators. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and ICF International.