ABSTRACT

Stressful life circumstances (e.g. violence and poverty) have been associated with elevated biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1), among older adults in high-income settings. Yet, it remains unknown whether these relationships exist among younger populations in resource-limited settings. We therefore utilised a cohort of 1,279 adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) from the HIV Prevention Trials Network 068 study in rural South Africa to examine the associations between 6 hypothesized stressors (intimate partner violence (IPV), food insecurity, depression, socioeconomic status (SES), HIV, childhood violence) and 3 biomarkers that were measured using dried blood spots (CRP, CMV, and HSV-1). Ordinal logistic regression estimated the lagged and cross-sectional associations between each stressor and each biomarker. IPV was cross-sectionally associated with elevated CMV (OR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.05,5.72), while low SES was cross-sectionally associated with reduced CMV (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.58,0.93). AGYW with HIV had elevated biomarkers cross-sectionally (CRP: OR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.08,2.09; CMV: OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.31,2.63; HSV-1: OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.17,2.41) and in a lagged analysis. The association between violence and CMV could help explain how violence results in stress and subsequently worse health among AGYW; however, additional research is needed to disentangle the longitudinal nature of IPV and stress.

Introduction

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in many parts of eastern and southern Africa face stressful life events that threaten their health and well-being, including food insecurity (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Citation2019) and intimate partner violence (IPV) (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Across the continent, it is estimated that 58% of African women are food insecure (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Citation2019), and one third will experience IPV in their lifetime (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Previous research primarily from high-income countries has demonstrated that commonly experienced stressors, like poverty and violence, can also activate the biological stress response and subsequently increase the risk of adverse health outcomes, including HIV infection (Aiello et al., Citation2010) and cardiovascular disease (Li & Fang, Citation2004). Furthermore, stress during adolescence can result in a more extreme, sustained biological response than similar experiences in adulthood which can affect brain development (Gunnar et al., Citation2009), highlighting the importance of examining these relationships during adolescence and young adulthood. Despite this evidence, few studies have examined the relationship between commonly experienced stressors and potential measures of biological stress in low-and-middle income countries or among AGYW.

When encountering a stressor, the brain launches a response involving the sympathetic – adrenal – medullary axis, the hypothalamic – pituitary – adrenal (HPA) axis, and the immune system (Piazza et al., Citation2010). Acute or chronic activation of these systems alters how the body responds to stress over time which can accelerate disease susceptibility and progression, resulting in poorer health (e.g. increased risk of chronic disease) (Segerstrom & Miller, Citation2004). Several biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1), are increasingly used as specific indicators of biological stress because they are proxies for immune function and susceptibility to infection on a population level (Blevins et al., Citation2017). CRP, a non-specific marker of inflammation (Danesh et al., Citation2004), elevates when systemic inflammation occurs due to impaired immune function. Previous studies have found that elevated CRP is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease later in life (Li & Fang, Citation2004) and with stressful life circumstances, including lower socioeconomic status (SES) (Liu et al., Citation2017). Herpesvirus biomarkers, such as CMV and HSV-1, also elevate in response to stressful events like violence or chronic stress over a period of time, such as food insecurity (Sainz et al., Citation2001). Once infected, herpesviruses persist throughout the lifetime, and during a stressful event, latent infections can reactivate, increase viral replication, and boost antibody production (Aiello et al., Citation2010; Sainz et al., Citation2001). Reactivation of these latent herpesviruses can increase susceptibility to other viruses (including HIV), although there is limited research examining biological markers of stress and HIV infection in this population (Aiello et al., Citation2010; Freeman et al., Citation2006).

CRP, HSV-1, and CMV have been associated with various stressors, such as poverty (Broyles et al., Citation2012), impaired mental health (Aiello et al., Citation2010; Glaser et al., Citation1985), and violence in childhood (Slopen et al., Citation2013) throughout the U.S. and Europe. Several studies have found associations between biomarkers and these stressors in Africa; however, the results are primarily cross-sectional, inconsistent, and do not examine a broad range of stressful life events. For example, there is some evidence that stress from living in an urban environment is associated with elevated cortisol among Black African men (Malan et al., Citation2012) and elevated CRP among Tanzanian women (Pinchoff et al., Citation2020). Higher CRP has also been found among Black South African women versus those of European descent (Tolmay et al., Citation2012) and as a marker of hypertension among rural Senegalese women (Lin et al., Citation2021). However, CRP and interleukin 6 were not associated with gender-based violence among Kenyan women, while cortisol was (Heller et al., Citation2018). After reviewing the literature, we are not aware of studies that have examined the relationship between stressors experienced during adolescence and biomarkers among AGYW in southern Africa.

The theory of stress and coping posits that stress results from an imbalance between perceived external or internal demands and the perceived personal and social resources to deal with them (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Therefore, while the biological stress response may be similar across populations, sources and responses to stress will differ by context and unevenly impact health and development. These relationships must be fully understood across contexts to develop appropriate interventions to reduce stress in youth to improve their overall health and well-being. Furthermore, the theory of threat and deprivation (Busso et al., Citation2017) states that stressors differentially impact the health of adolescents depending on whether the stressor is a ‘threat’ (an exposure to harm or threat of harm, like violence) or ‘deprivation’ (an absence of expected inputs from the environment or structural barriers, like food insecurity).

Given this framework, a secondary analysis of the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 068 Study (Pettifor et al., Citation2016) was conducted to measure the association between six experiences of pervasive stressors (IPV, food insecurity, depression, low SES, positive HIV status, and childhood violence) and three different biomarkers (CRP, CMV, and HSV-1) among AGYW in rural South Africa. We included stressors that both threaten one’s health and well-being (IPV, childhood abuse) and those that are structural forms of deprivation (food insecurity, low SES). We also included two additional stressors, HIV status and depression, given the area’s high HIV prevalence (Gómez-Olivé et al., Citation2013), the stress associated with HIV-related stigma (Rueda et al., Citation2016), and the hypothesized impact of poor mental health on stress (Sahu et al., Citation2022). We hypothesized that experiencing any of these stressors would be associated with elevated levels of CRP, CMV, and HSV-1. However, HIV status may operate through a different pathway given that it is a virus that affects immune function.

Materials and methods

Study design & population

This cohort study was nested within HPTN 068 (NCT01233531) (Pettifor et al., Citation2016), a randomised controlled trial measuring the effectiveness of a cash transfer, conditional upon school attendance, on HIV incidence among AGYW. In HPTN 068, participants were randomised 1:1 to receive a monthly cash transfer or the standard of care for up to three years. The study was conducted within the Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System (AHDSS) (Gómez-Olivé et al., Citation2013) in the Bushbuckridge subdistrict of Mpumalanga province, a rural area characterised by high levels of HIV (23.9% prevalence among women) (Gómez-Olivé et al., Citation2013) and socioeconomic stressors (Pettifor et al., Citation2016). Eligible participants were AGYW from the AHDSS who were ages 13–20, enrolled in grades 8–11, unmarried, not pregnant, and literate. Eligibility criteria have been described in full elsewhere (Pettifor et al., Citation2016). Participants provided written informed consent or assent (if under age 18). Ethical approval was obtained from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board and the University of Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee. All research procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study procedures

Four annual visits occurred during the main trial period (2011–2015) that measured sexual behaviour and sociodemographic factors using Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview and tested for incident HIV-1 and Herpes Simplex Virus Type II (HSV-2) infections. Two additional post-intervention visits were conducted in 2015–2017 and 2018–2019 to collect information via self-interview on sociodemographic factors, stressors, and HIV-1/HSV-2 status. Biomarkers were collected at the final visit (2018–2019) via dried blood spots (DBS). Participants who completed both post-intervention visits and had available biomarker information were included in this cohort to examine how stressors measured concurrently (first aim) and at a prior time point (second aim) influence biomarker levels.

Study measures

Stressors & health

Stressors were identified based on their hypothesized impact and the theory of threat and deprivation (Busso et al., Citation2017), which suggests that threats are more likely to activate the HPA-axis resulting in a stronger hormonal stress response than measures of deprivation. We therefore selected two stressors that were threats (IPV, childhood abuse) and two that were deprivation measures (food insecurity, low SES). We also examined relationships between the biomarkers and two other stressors, depression, and HIV, given the relationship between HIV and other latent herpesviruses (Aiello et al., Citation2010), the area’s high HIV prevalence (Gómez-Olivé et al., Citation2013), the large burden of social stress associated with HIV-related stigma (Rueda et al., Citation2016), and the hypothesized impact of depression on stress (Sahu et al., Citation2022). All stressors except childhood violence were measured at both post-intervention visits. Childhood violence (violence occurring before age 18) was retrospectively assessed at the 2015–2017 visit only.

IPV was defined as an experience of physical and/or sexual violence perpetrated by an intimate male partner in the past 12 months and was measured using eight questions from the World Health Organization’s Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Questionnaire (World Health Organization, Citation2005). Childhood violence was considered a report of emotional or physical violence perpetrated by a parent, guardian, or other household member before age 18. HIV status was defined as an HIV diagnosis at any prior visit because this analysis sought to examine how known HIV status operates due to the discrimination that people living with HIV encounter (Rueda et al., Citation2016). Two rapid tests were used to screen for HIV infection (Determine HIV-1/2 test; Uni-gold Recombigen HIV test). Confirmatory testing was conducted as needed (GS HIV-1 western blot assay) (Pettifor et al., Citation2016). Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (depression defined as ≥16 points) (Radloff, Citation1977). Food insecurity was defined as worrying about having enough food in the past year or going to sleep hungry more than one or two nights in the past month. Per capita household consumption was used as a proxy for SES (Kilburn et al., Citation2019). Additional variables included self-rated physical health (better vs. worse health), self-perceived stress (using the Sheldon Cohen Perceived Stress Scale) (Cohen et al., Citation1983), age, study arm (intervention vs. control), and HSV-2 serostatus. Details on the use of these additional variables can be found in the statistical analysis section.

Biomarkers

The primary outcomes were CRP, CMV, and HSV-1 levels that were collected at the final post-intervention visit via DBS. Samples were treated with dehumidify cards, stored immediately, and processed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) at Neuberg Global laboratory, South Africa. CMV and HSV-1 optical density (OD) levels were measured using Trinity Biotech CaptiaTM CMV IgG Enzyme-Linked Immunosobent Assay (ELISA) and Trinity Biotech CaptiaTM HSV-1 IgG ELISA respectively, with OD levels approximating antibody titers (e.g. low OD approximating low antibody titer). CRP was measured using the Sandwich ELISA (McDade et al., Citation2004). CMV and HSV-1 were highly prevalent among participants, so ordinal CMV and HSV-1 variables were created with four levels: seronegative (0), followed by seropositive OD tertiles (1 = low, 2 = medium, 3 = high). This is consistent with other estimates across the continent (82% of African adults are estimated to be CMV seropositive, and more than 90% are estimated to be HSV-1 seropositive) (Bates & Brantsaeter, Citation2016; Harfouche et al., Citation2019). CRP levels were divided into quartiles (lowest CRP = 1st quartile; highest CRP = 4th quartile) because the distribution of CRP (mg/L) was highly right skewed and to be consistent with the other biomarker variables. In our preliminary work, the biomarkers were operationalised as continuous variables; however, previous studies have enhanced the interpretability of their findings by using ordinal outcomes (Roberts et al., Citation2010). Additionally, the non-normal biomarker distributions and limited clinical importance of continuous measures supported the use of ordinal measures.

Statistical analysis

First, we present descriptive results comparing key demographic factors and stressors in the study population, stratified by biomarker level. In this descriptive table, CMV and HSV-1 were stratified by serostatus (seropositive vs. seronegative), and CRP was dichotomised into either low (1st quartile) or high levels (combining quartiles 2–4). These categorizations were used to provide preliminary insight into how demographic factors varied by each biomarker level. Here we do not present the 4 ordinal categories (described above) for ease of interpretation and due to space constraints.

To address the first statistical aim, ordinal logistic regression was used to estimate proportional odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between each stressor and each biomarker (CRP, CMV, and HSV-1) measured at the same time point (in 2018–2019). Here, the 4-level ordinal biomarker levels described in the Biomarkers sub-section are used. To better understand the effect of physical health, the association between self-rated physical health and each biomarker was also assessed. Covariates for each model were identified from directed acyclic graphs (Pearl, Citation1995) and are presented in the tables below. Most covariates had limited missing data (<4%), but multiple imputation was used to impute any missing values. We also assessed whether continuous biomarker levels were correlated with self-perceived stress by conducting Pearson correlation tests. To address the second statistical aim, the same methods were used (multivariable ordinal logistic regression) to estimate the lagged associations between each stressor (measured in 2015–2017) and each biomarker (measured in 2018–2019). All statistical tests were 2-sided using an alpha value of 0.05; analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Demographics and biomarker distributions

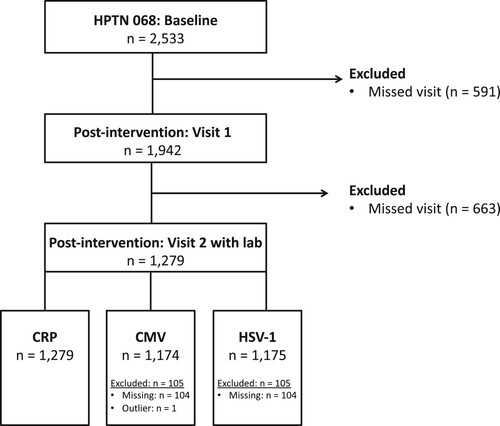

Of the 2,533 AGYW enrolled in HPTN 068, 1,279 (50.5%) completed both post-intervention visits and were included in this nested cohort (). At the 2015–2017 visit, most participants were food secure (74.5%), had completed school or were in school (88.1%), and reported excellent or very good physical health (70.2%) (). The median age in the cohort was 20 (interquartile range (IQR): 19,21) and 23 at the 2018–2019 visit (IQR: 22,24). Six percent of participants had a previously diagnosed HIV infection at the 2015–2017 visit, and 23.4% were HSV-2 seropositive.

Table 1 . Demographic characteristics of a cohort of young South African women, stratified by biomarker levelsTable Footnotea.

The CRP distribution was highly right skewed, such that the majority had CRP values less than 1 mg/L (median: 0.90 mg/L, IQR: 0.60,1.50). CMV and HSV-1 OD values were more normally distributed than CRP but were also right skewed. The median CMV OD value was 0.96 (IQR: 0.64,1.25), and the median HSV-1 OD value was 0.54 (IQR: 0.26,0.96). Most participants were CMV (87.0%) and HSV-1 (70.5%) seropositive ().

Associations between stressors and biomarkers

Having a prevalent HIV diagnosis was associated with elevated biomarkers at the following visit (CRP: OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 0.98,2.28; CMV: OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.05,2.53; HSV-1: OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.09,2.78) and concurrently (CRP: OR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.08,2.09; CMV: OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.31,2.63; HSV-1: OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.17,2.41) (). Among AGYW who experienced IPV in the past year, the proportional odds of having elevated CMV values at the same time point was 2.5 times that of AGYW without recent IPV experiences (OR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.05,5.72). This association was not present in the lagged analysis (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.71,1.47). While not statistically significant, AGYW who experienced IPV had higher CRP (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 0.74,3.12) and HSV-1 levels (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 0.61,2.75) in the cross-sectional analysis. Moreover, young women who experienced childhood abuse had elevated CMV (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.95,1.60).

Table 2 . Associations between stressors and biomarkers among a cohort of adolescent girls and young women in rural South AfricaTable Footnotea.

Some stressors were associated with decreased biomarker levels. For AGYW with low SES, the proportional odds of having elevated CMV levels at the same time point was 27% lower compared to those with higher SES (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.58,0.93), but this association was not present in the lagged analysis (OR = 1.14, 95% CI: 0.89, 1.45) (). Depression may be associated with lower HSV-1 levels at the following visit (OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.62,1.02) and concurrently (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.54,1.12); however, these findings were not statistically significant. Similarly, there was preliminary signal that food insecurity may be cross-sectionally associated with lower CMV (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.49,1.04) and HSV-1 (OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.59,1.25), although this was not statistically significant.

Association with physical health and perceived stress

Worse self-rated physical health was not associated with any biomarkers at the following visit (CRP: OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.77,1.19; CMV: OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.84,1.33; HSV-1: OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.92,1.45) or the same visit (CRP: OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.74,1.13; CMV: OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.74,1.13; HSV-1: OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.75,1.25) (). Perceived stress was not correlated with any of the continuous biomarker measures at that same time point (correlation coefficients: CRP = −0.02, CMV = 0.00, HSV-1 = – 0.02).

Discussion

In this sample of young women from rural South Arica, HIV status was associated with elevated levels of all 3 biomarkers, both concurrently and in a lagged analysis. Additionally, recent IPV was cross-sectionally associated with elevated CMV, and low SES was cross-sectionally associated with lower CMV. These results align with the theory of threat and deprivation (Busso et al., Citation2017) which proposes that threats (like IPV) are more likely to activate the HPA-axis resulting in hormonal stress than deprivation (e.g. poverty). These findings also support research which has observed associations between biomarkers and IPV among older American women (Newton et al., Citation2011) and Tanzanian children (Slopen et al., Citation2018). Thus, biological stress could be a pathway through which experiences of violence impact health; however, these biomarkers may also elevate through pathways other than stress. Experts have hypothesized that herpesviruses likely reactivate due to an amalgamation of factors (Suzich & Cliffe, Citation2018). Interestingly, we did not observe a relationship between self-rated physical health or perceived stress and any of the biomarkers. However, it may be difficult to observe this association in a sample of young women who reported relatively good health. Ultimately, the findings from this study suggest that CMV could be used as an indicator of certain stressors among AGYW in rural southern Africa; however, longitudinal data is needed to disentangle the temporality of these relationships. Furthermore, factors like elevated BMI (Aronson et al., Citation2004) and other chronic conditions (Li & Fang, Citation2004) may confound or mediate some relationships, resulting in different patterns between SES than what has been observed in high income settings.

The association between low SES and lower CMV levels could be explained by the biomarkers’ relationship with other chronic diseases that are more prevalent among wealthier groups in South Africa. This trend differs from countries like the U.S., where lower SES is associated with higher biomarker levels. In the U.S., chronic disease more often occurs in lower income populations (Oates et al., Citation2017) and those with higher biomarker levels (Li & Fang, Citation2004). South Africa is earlier in its epidemiological transition than the U.S. (Kabudula, Houle, Collinson, Kahn, Gómez-Olivé, Clark, et al., Citation2017), so chronic conditions are more common among wealthier participants, rather than those of lower SES (Kobayashi et al., Citation2019). It is expected that with time, a transition will occur and those with lower SES in South Africa will be at a greater risk of chronic conditions, as has happened with HIV (Kabudula, Houle, Collinson, Kahn, Gómez-Olivé, Tollman, et al., Citation2017). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine whether BMI, which has been associated with chronic health and with CRP (Aronson et al., Citation2004), was associated with the biomarkers in our study. We found that BMI was associated with higher CRP levels, suggesting that BMI could mediate the relationship between stressful factors and these biomarkers, and again highlighting the importance of chronic conditions.

The strongest association in our study was between HIV status and the herpesvirus biomarkers (CMV and HSV-1). However, it remains unclear whether this is due to a true biological relationship between these herpesviruses and HIV, or due to the increased psychosocial stress that people living with HIV encounter (Rueda et al., Citation2016). Previous studies have found that herpesviruses, including CMV and HSV-1, are associated with an increased risk of HIV infection and disease progression (Freeman et al., Citation2006), and that herpesviruses can become reactivated in people living with HIV, activate CD4+ T cells, and result in sustained cell immune activation (Aiello et al., Citation2010). Beyond this biologic pathway, there is well-documented evidence of the psychosocial stress people living with HIV experience (e.g. HIV-related stigma) (Rueda et al., Citation2016). More research is needed to untangle the degree to which the relationship between HIV and herpesviruses is a biologic property of these viruses or due to social factors.

This study is, to our knowledge, one of the first to assess the association between stressful life events and biomarkers among AGYW in southern Africa. Adolescence is a critical life stage where stress elicits a stronger biological response and impacts brain development; however, most research has been conducted in high-income settings or among older populations (Aiello et al., Citation2010; Broyles et al., Citation2012; Slopen et al., Citation2013). This study is further strengthened by the use of valid, sensitive, precise, and theory-driven biomarkers. A substantial body of literature has demonstrated relationships between psychosocial stress and these biomarkers (Broyles et al., Citation2012; Glaser et al., Citation1985; Slopen et al., Citation2013), and between these biomarkers and health (Freeman et al., Citation2006; Li & Fang, Citation2004). The use of multiple markers in this study increased the opportunity to identify associations that had not been previously studied in this population and to ensure consistent associations. Our choice of biomarkers was further strengthened by the fact that they could be collected via DBS, potentially a more feasible, acceptable method in resource-limited settings than venipuncture (Lin et al., Citation2021).

This study was limited by attrition from the original trial to the cohort (). It is possible that those retained throughout the cohort were less likely to experience stressors or were healthier than those who were lost-to-follow-up. Thus, these findings may not be generalizable to the original study population or to AGYW in other rural African settings. However, the sample size was still sufficiently large to provide relatively precise estimates. This study was also limited by unmeasured confounding, given that it was impossible to account for all stressors that AGYW could encounter, or other factors related to health and immune function. Additionally, most AGYW had low CRP levels and were CMV and/or HSV- 1 seropositive. Because age is a strong predictor of CRP (Wyczalkowska-Tomasik et al., Citation2016), it is unsurprising that this young, relatively healthy population had low CRP values. For comparison, a cohort of slightly older young adults from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (mean age = 29), had a mean CRP value of 1.92 mg/L (also collected via DBS) (Blevins et al., Citation2017). Given the theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), which suggests that stress is context specific, this U.S. comparison should be considered cautiously. Lastly, we did not examine longitudinal trajectories of stress throughout adolescence, which may provide more insight into the relationship with these biomarkers than a single time point.

Conclusion

Among a sample of AGYW in rural South Africa, positive HIV status was associated with elevated CRP, CMV, and HSV-1 at the same time point and in lagged analyses. IPV was cross-sectionally associated with elevated CMV while low SES was cross-sectionally associated with lower CMV. Additional research is needed to understand the degree to which the relationship between HIV and herpesviruses is a biologic property of these viruses or due to social factors, such as stigma. Given the relationship between IPV and CMV, increased biological stress may be one pathway through which violence impacts adverse health outcomes and could be interrupted with violence prevention interventions. Additional research is needed to better understand whether findings related to structural deprivation (e.g. low SES) are affected by South Africa’s progression through an epidemiologic transition.

Acknowledgements

We thank the HPTN 068 study team and all trial participants. The MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit and Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System have been supported by the University of the Witwatersrand, the Medical Research Council, South Africa, and the Wellcome Trust, UK (grants 058893/Z/99/A; 069683/Z/02/Z; 085477/Z/08/Z; 085477/B/08/Z).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aiello, A. E., Simanek, A. M., & Galea, S. (2010). Population levels of psychological stress, herpesvirus reactivation and HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 14(2), 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9358-4

- Aronson, D., Bartha, P., Zinder, O., Kerner, A., Markiewicz, W., Avizohar, O., Brook, G. J., & Levy, Y. (2004). Obesity is the major determinant of elevated C-reactive protein in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Obesity, 28(5), 674–679. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802609

- Bates, M., & Brantsaeter, A. B. (2016). Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) in Africa: A neglected but important pathogen. Journal of Virus Eradication, 2(3), 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30456-8

- Blevins, C. L., Sagui, S. J., & Bennett, J. M. (2017). Inflammation and positive affect: Examining the stress-buffering hypothesis with data from the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 61, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2016.07.149

- Broyles, S. T., Staiano, A. E., Drazba, K. T., Gupta, A. K., Sothern, M., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2012). Elevated C-reactive protein in children from risky neighborhoods: Evidence for a stress pathway linking neighborhoods and inflammation in children. PloS One, 7(9), e45419. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045419

- Busso, D. S., McLaughlin, K. A., & Sheridan, M. A. (2017). Dimensions of adversity, physiological reactivity, and externalizing psychopathology in adolescence: Deprivation and threat. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(2), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000369

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Danesh, J., Wheeler, J. G., Hirschfield, G. M., Eda, S., Eiriksdottir, G., Rumley, A., Lowe, G. D. O., Pepys, M. B., & Gudnason, V. (2004). C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 350(14), 1387–1397. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa032804

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2019). The state of food security and nutrition in the world: Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. FAO.

- Freeman, E. E., Weiss, H. A., Glynn, J. R., Cross, P. L., Whitworth, J. A., & Hayes, R. J. (2006). Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies, Aids (london, England), 20(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7

- Glaser, R., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Speicher, C. E., & Holliday, J. E. (1985). Stress, loneliness, and changes in herpesvirus latency. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(3), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00870312

- Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Angotti, N., Houle, B., Klipstein-Grobusch, K., Kabudula, C., Menken, J., Williams, J., Tollman, S., & Clark, S. J. (2013). Prevalence of HIV among those 15 and older in rural South Africa. AIDS Care, 25(9), 1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.750710

- Gunnar, M. R., Wewerka, S., Frenn, K., Long, J. D., & Griggs, C. (2009). Developmental changes in hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal activity over the transition to adolescence: Normative changes and associations with puberty. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000054

- Harfouche, M., Chemaitelly, H., & Abu-Raddad, L. J. (2019). Herpes simplex virus type 1 epidemiology in Africa: Systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Journal of Infection, 79(4), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2019.07.012

- Heller, M., Roberts, S. T., Masese, L., Ngina, J., Chohan, N., Chohan, V., Shafi, J., McClelland, R. S., Brindle, E., & Graham, S. M. (2018). Gender-Based Violence, Physiological Stress, and Inflammation: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 27(9), 1152–1161. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6743

- Kabudula, C. W., Houle, B., Collinson, M. A., Kahn, K., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Clark, S. J., & Tollman, S. (2017). Progression of the epidemiological transition in a rural South African setting: Findings from population surveillance in Agincourt, 1993–2013. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 424. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4312-x

- Kabudula, C. W., Houle, B., Collinson, M. A., Kahn, K., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Tollman, S., & Clark, S. J. (2017). Socioeconomic differences in mortality in the antiretroviral therapy era in Agincourt, rural South Africa, 2001–13: A population surveillance analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 5(9), e924–e935. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30297-8

- Kilburn, K., Hughes, J. P., MacPhail, C., Wagner, R. G., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Kahn, K., & Pettifor, A. (2019). Cash Transfers, Young Women’s Economic Well-Being, and HIV Risk: Evidence from HPTN 068. AIDS and Behavior, 23(5), 1178–1194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2329-5

- Kobayashi, L. C., Frank, S., Riumallo-Herl, C., Canning, D., & Berkman, L. (2019). Socioeconomic gradients in chronic disease risk behaviors in a population-based study of older adults in rural South Africa. International Journal of Public Health, 64(1), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1173-8

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Li, J.-J., & Fang, C.-H. (2004). C-reactive protein is not only an inflammatory marker but also a direct cause of cardiovascular diseases. Medical Hypotheses, 62(4), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.014

- Lin, Y., Wang, X., Lenz, L., Ndiaye, O., Qin, J., Wang, X., Huang, H., Jeuland, M. A., & Zhang, J. (2021). Dried blood spot biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation associated with blood pressure in rural Senegalese women with incident hypertension. Antioxidants, 10(12), 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10122026

- Liu, R. S., Aiello, A. E., Mensah, F. K., Gasser, C. E., Rueb, K., Cordell, B., Juonala, M., Wake, M., & Burgner, D. P. (2017). Socioeconomic status in childhood and C reactive protein in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(8), 817–826. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-208646

- Malan, L., Hamer, M., Reimann, M., Huisman, H., Van Rooyen, J., Schutte, A., Schutte, R., Potgieter, J., Wissing, M., Steyn, F., Seedat, Y., & Malan, N. (2012). Defensive coping, urbanization, and neuroendocrine function in Black Africans: The THUSA study. Psychophysiology, 49(6), 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01362.x

- McDade, T. W., Burhop, J., & Dohnal, J. (2004). High-Sensitivity enzyme immunoassay for C-reactive protein in dried blood spots. Clinical Chemistry, 50(3), 652–654. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2003.029488

- Newton, T. L., Fernandez-Botran, R., Miller, J. J., Lorenz, D. J., Burns, V. E., & Fleming, K. N. (2011). Markers of inflammation in midlife women with intimate partner violence histories. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 20(12), 1871–1880. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2788

- Oates, G. R., Jackson, B. E., Partridge, E. E., Singh, K. P., Fouad, M. N., & Bae, S. (2017). Sociodemographic patterns of chronic disease: How the Mid-south region compares to the rest of the country. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(Suppl 1), S31–S39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.004

- Pearl, J. (1995). Causal diagrams for empirical research. Biometrika, 82(4), 669–688. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/82.4.669

- Pettifor, A., MacPhail, C., Hughes, J. P., Selin, A., Wang, J., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Eshleman, S. H., Wagner, R. G., Mabuza, W., Khoza, N., Suchindran, C., Mokoena, I., Twine, R., Andrew, P., Townley, E., Laeyendecker, O., Agyei, Y., Tollman, S., & Kahn, K. (2016). The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): A phase 3, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 4(12), e978–e988. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30253-4

- Piazza, J. R., Almeida, D. M., Dmitrieva, N. O., & Klein, L. C. (2010). Frontiers in the use of biomarkers of health in research on stress and aging. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(5), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq049

- Pinchoff, J., Mills, C. W., & Balk, D. (2020). Urbanization and health: The effects of the built environment on chronic disease risk factors among women in Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0241810. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241810

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Roberts, E. T., Haan, M. N., Dowd, J. B., & Aiello, A. E. (2010). Cytomegalovirus antibody levels, inflammation, and mortality among elderly latinos over 9 years of follow-up. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq177

- Rueda, S., Mitra, S., Chen, S., Gogolishvili, D., Globerman, J., Chambers, L., Wilson, M., Logie, C. H., Shi, Q., Morassaei, S., & Rourke, S. B. (2016). Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453

- Sahu, M. K., Dubey, R. K., Chandrakar, A., Kumar, M., & Kumar, M. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of serum and plasma cortisol levels in depressed patients versus control. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(5), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_561_21

- Sainz, B., Loutsch, J. M., Marquart, M. E., & Hill, J. M. (2001). Stress-associated immunomodulation and herpes simplex virus infections. Medical Hypotheses, 56(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1054/mehy.2000.1219

- Segerstrom, S. C., & Miller, G. E. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 601–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601

- Slopen, N., Kubzansky, L. D., McLaughlin, K. A., & Koenen, K. C. (2013). Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(2), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.013

- Slopen, N., Zhang, J., Urlacher, S. S., De Silva, G., & Mittal, M. (2018). Maternal experiences of intimate partner violence and C-reactive protein levels in young children in Tanzania. SSM - Population Health, 6, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.09.002

- Suzich, J. B., & Cliffe, A. R. (2018). Strength in diversity: Understanding the pathways to herpes simplex virus reactivation. Virology, 522, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2018.07.011

- Tolmay, C. M., Malan, L., & Van Rooyen, J. M. (2012). The relationship between cortisol, C-reactive protein and hypertension in African and causcasian women : The POWIRS study. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 23(2), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.5830/CVJA-2011-035

- World Health Organization. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against Women.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240022256.

- Wyczalkowska-Tomasik, A., Czarkowska-Paczek, B., Zielenkiewicz, M., & Paczek, L. (2016). Inflammatory markers change with age, but do not fall beyond reported normal ranges. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis, 64(3), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00005-015-0357-7