ABSTRACT

There is limited information about how the mental health of people has changed over time during the COVID-19 pandemic in low- and middle-income countries. In a cross-sectional study, we identified factors associated with psychological distress at two periods immediately after two peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia. Data were collected via online surveys. In May–June 2020, we surveyed 373 respondents across Russia. In January-February 2021, we surveyed 743 people, using the same approach for survey distribution. With Kessler-10 as a measure of psychological distress, we used regression analysis to determine factors associated with higher psychological distress among Russians. Levels of psychological distress were high in both time periods and did not significantly change between the surveys. Having had COVID-19, losing one’s job, experiencing problems accessing healthcare, and changing drinking behaviour during the pandemic were associated with higher psychological distress. Apart from getting sick or worrying about the virus, psychological distress is affected by restrictions and the consequences of the pandemic situation. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, actions are needed to address the mental well-being of the population in Russia.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on people’s lives worldwide. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, public health researchers have been calling attention to the toll the pandemic is taking on people’s mental health and well-being (Gunnell et al., Citation2020; Holmes et al., Citation2020; Pfefferbaum & North, Citation2020; Kumar & Nayar, Citation2021). At the early stage of the pandemic, the prevalence of mental health problems among the general population was significantly higher than pre-pandemic population estimates (Daly & Robinson, Citation2021; Ettman et al., Citation2020; Killgore et al., Citation2021; McGinty et al., Citation2020; Sønderskov et al., Citation2020). Less is known about how the mental health of people has changed over time during the prolonged pandemic. The mental health of the US population returned to pre-pandemic level by mid-summer 2020 (Das et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022). In contrast to these findings, a study exploring mental health at the onset of the pandemic and 6 months later in Austria showed no change in mental health over time during the pandemic (Pieh et al., Citation2021). The study exploring mental health in Romania in May and November 2020 showed no statistically significant change in clinically relevant scores between two surveys (Vancea & Apostol, Citation2021). Some of these changes or lack of changes in the mental health status of populations may depend on the ‘waves’ that the COVID-19 pandemic seems to follow with recurring upward and downward periods in terms of daily cases and deaths.

While the results described above may indicate that apocalyptic predictions that the pandemic would be a mental health catastrophe have not yet come true, even a small rise in mental health issues may have important cumulative consequences on the population level. While previous studies explored the mental health problems surge at the onset of the pandemic, a more detailed understanding of how the pandemic affects mental health is warranted as COVID-19 persists. To evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health worldwide, studies in different institutional settings and under different policy responses are necessary. Particularly, there is gap in the literature on the pandemic’s mental health toll in low- and middle-income countries.

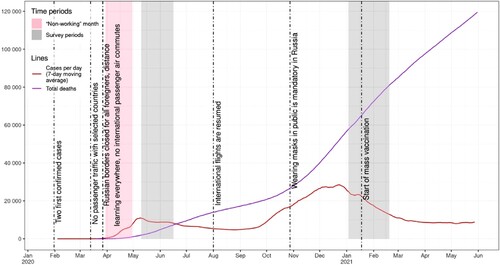

Russia is among the countries hardest hit by the pandemic. Cumulative excess mortality in Russia for the period from February 26 to December 31, 2020, was 244.73 deaths per 100 0000, surpassed only by Peru and Bulgaria among 67 countries included in the analysis (Sanmarchi et al., Citation2021). Although the first two cases of COVID-19 infection in Russia were recorded as early as January 31, the rapid spread of the disease began in March 2020. It forced the government to introduce internal movement restrictions, stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on gatherings, and bans for public events. Work closure that affected all but essential workplaces started on March 30 and lasted until May 11. Schools were closed for in-person learning from March 14 until the end of the 2020 academic year. The mandatory wearing of masks was introduced on May 12, the same time as the first wave of COVID-19 peaked at 11,000 new cases that day (, cases per day shown as the cumulative 7-day average). By the end of the month, it had dropped to 8700, and the Russian government started lifting restrictions. The number of daily cases detected continued to fall until it reached a low of 4700 in early August 2020.

Figure 1. Development of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia and imposed containment measures January February 2020–June 2021. Source for cases and death data: (Guidotti & Ardia, Citation2020).

Starting in the second half of September 2020, the number of cases detected daily began to grow rapidly. In the first half of October, it surpassed the record of mid-May and continued to rise. The increase lasted until the end of December. Although the epidemiological situation during the second wave of COVID-19 was much worse than during the first wave, government measures to contain the disease were much less extensive. For example, workplace closures were never introduced, stay-at-home was recommended only for vulnerable groups, and internal travel was not restricted. Russian policies to contain the disease later relied on less restrictive measures such as mask wearing.

A comparative analysis of policy response measures taken by the Russian government (Åslund, Citation2020; Nemec et al., Citation2021) demonstrates that it was less successful in preventing mortality compared with other countries. There are at least three important aspects that set Russia’s policy approach apart from other countries. First, while the initial response was similar to that of other countries, the measures were eased early and never reintroduced in full scale. Second, Russia turned out to be less capable of promoting the measures compared to other countries (Nemec et al., Citation2021). Third, pandemic-related budgetary allocations were oriented mostly towards big companies, instead of small and medium enterprises and households (Vakulenko et al., Citation2020).

There is limited information about the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia. Existing studies on mental health in Russia during the pandemic (Nekliudov et al., Citation2020; Zinchenko et al., Citation2021) were conducted during the early stage of the spread of COVID-19. Findings indicate that time spent following COVID-19-related news and employment loss during pandemics were important factors associated with anxiety (Nekliudov et al., Citation2020). Pre-COVID-19 estimates of anxiety and depression levels were significantly lower (Zinchenko et al., Citation2021). These studies were conducted very early in the pandemic and more information is warranted on the psychological impact of the prolonged pandemic. Two cross-national studies (Ochnik et al., Citation2021; Brailovskaia et al., Citation2021) allow for a comparison of mental health prevalence in Russia to other countries. Both studies show that Russia demonstrates patterns similar to other countries. For example, the mean depression score (PHQ-8) in Russia was higher than in Slovenia, Czechia, Ukraine, Germany, and Israel, but lower than in Poland, Turkey, and Columbia (Ochnik et al., Citation2021). Again, both studies were conducted early in the pandemic (May–July 2020 for Ochnik et al., Citation2021, March-September 2020 for Brailovskaia et al., Citation2021), and that is important, as Russia’s policy response during the spring of 2020 was similar to other countries, while its regulations during the fall of 2020 differed substantially. Therefore, more information is warranted about the psychological distress experienced overtime during the pandemic, as both the threat of COVID-19 continued but there were also the economic and social consequences of the prolonged restrictions in place.

In our study, we aimed to examine factors associated with psychological distress at two important time periods during the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia (May–June 2020 and January–February 2021). We used a cross-sectional study design and collected survey data at two time periods that coincided with peaks in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to tracking observed changes in the levels of psychological distress, our research aimed to test the following hypotheses in regard to what factors may be associated with psychological distress:

Psycholgical distress is associated with the perceived risk of COVID-19 infection.

Psycholgical distress is associated with economic and social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (as measured in this study by job loss, alcohol consumption, and access to necessary healthcare services).

Our study contributes to the literature on how changes in everyday life associated with the pandemic and restrictions were related to psychological distress.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Data were collected twice during the coronavirus pandemic in Russia using online, self-administered surveys delivered by Google Forms. The first survey was distributed from May 10 to June 16, 2020 (Survey 1); and the second was distributed from January 3 to February 19, 2021 (Survey 2). These two time periods coincided with the first two distinct waves of COVID-19 in Russia. We used a convenience sampling approach, informed by the snowballing method of data collection. Recruitment was done through emailing and posting via social media sites in order to reach participants from different regions across Russia. The same individuals did not necessarily participate in both surveys, and while our data are not panel data, the fact that the survey was distributed in a similar way, our two samples are close in terms of socio-demographic structure (). Respondents were required to be over 18 years of age and reside in Russia during the pandemic. Participants acknowledged their informed consent to participate and completed the anonymous online survey. After completing the survey, respondents were presented with a link to help further distribute the survey to others. The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the St. Petersburg Association of Sociologists.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of respondents in Survey 1 and Survey 2.

While a total of 391 and 809 participated in the survey, we removed respondents from the analysis if there were any missing responses from the Kessler-10 questionnaire on psychological distress given that this measurement is valid only if all items are completed. We also removed observations from the final analysis if there were missing values for any of the explanatory variables. We used Little’s MCAR test to confirm that our missing data were random. Our final sample for the analysis in this study was 373 and 743.

Instruments and measures

Our main outcome of interest was psychological distress, which was measured using The Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., Citation2002). Kessler 10 is a widely used and well-validated 10-item questionnaire intended to assess non-specific general mental health-related functioning and distress experienced in the most recent 4-week period. Ten items assessed the frequency of distress symptoms on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Points from the questions were summed up into a final score, ranging from 10 to 50 points. Higher scores indicated more severe distress. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.93 in both survey waves.

To determine respondents COVID-19 status, participants were asked if they currently have or had a COVID-19 infection in the past. For analysis, participants were then classified into three groups: no infection, tested positive or suspected infection with COVID-19, and did not know. Participants were also asked if any of their relatives or acquaintances currently had COVID-19 or had it in the past and grouped into two categories for analysis: Yes, confirmed by the test or suspected, or No.

Participants were asked about underlying medical conditions that put them at high risk of serious, life-threatening complications from COVID-19, including cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), heart conditions (heart failure, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies or hypertension), diabetes (type 1 or type 2), or hepatitis B. For analysis, participants were grouped as ‘high-risk’ or not. As a measure of the perceived risk of being infected with COVID-19 question, participants were asked ‘How do you assess the risks for you personally of contracting the coronavirus?’ Possible response categories included unlikely, possible, significant, or high.

Two sets of variables were included to assess the effect of pandemic situation: (i) healthy lifestyle changes and (ii) job market changes. Healthy lifestyle changes included questions about alcohol consumption and utilisation of healthcare services. Changes in alcohol use were measured with questions about both frequency and amount of consumption. Participants were asked if they had to cancel planned visits to their doctor, cancel scheduled surgical procedures, or cancel treatment services due to the pandemic. Job market changes were measured with three survey items, including individual job loss, places on unpaid leave, and working remotely.

Participants reported their age, gender, marital status (married vs. single or divorced or widowed), educational qualifications (university degree, no degree), per-capita household monthly income (grouped into four categories: <20 k rub., 20 k – 40 k rub., 40–60, >60 k. rub), employment status during the pandemic (currently working, currently not working), and size of settlement where they reside.

Data analysis

To ensure that the baseline assessment (10 May–16 June) was comparable to the subsequent survey (3 January–19 February), a series of t-tests were conducted to confirm that the levels of each demographic characteristic in Survey 1 were similar to the those in Survey 2 (). Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used to assess the relationship between COVID-19 and restrictions-related variables and the K10 distress score. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were included as controls to reduce heterogeneity and receive more reliable estimates. The confidence level was set at 95% and a p < = .05 was considered statistically significant. The main model included three specifications: only COVID-19-related variables, only restrictions-related variables, and both COVID-19-related variables and restrictions-related variables. As a robustness check, a set of models was estimated with only one variable of interest included and adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (Supplementary Table 1). To explore if the change over time between the two surveys has led to changes in the underlying relationship between the variables in the model, the former models were expanded by including the interaction terms between variables of interest and the Survey 2 dummy (Supplementary Table 2).

Results

The sociodemographic information of participants was similar in both survey points in regard to gender distribution (74% women), mean age (37 years), the share of married (47%), and the share of currently not working respondents (20%). The share of people with an income of more than 60 thousand rubles was higher in Survey 1 (25%) compared to Survey 2 (18%), as well as the proportion of respondents living in cities with a population of 100–500 thousand people (23% in Survey 1 vs. 10% in Survey 2).

COVID-19 infection differed between the two surveys. In Survey 1, just 1% reported that they had been diagnosed with or suspected they had been sick with the virus. While in Survey 2, 35% reported having contracted COVID-19. These changes in the epidemiological situation were reflected in the growing share of people who estimated their risk of getting COVID-19 as substantial (rise of 7 pp) and high (rise of 6 pp). The share of people who lost employment during the pandemic increased from 3% to 6%, change in the share of respondents who started working remotely was not statistically significant. In both surveys, respondents reported high rates of psychological distress. The mean score on Kessler 10 among males was 20.2 in Survey I and 19.6 in Survey 2 (p = 0.52). The mean score among females was 22.6 in Survey I and 22.4 in Survey 2 (p = 0.66).

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

Gender, age, marital status, and income were statistically significant in both surveys, with no change between the two surveys. Women, younger people, unmarried and lower-income had higher psychological distress. Education was not statistically significant in either survey, with no change between the two surveys. Not being in the labour force and living alone was marginally significant with psychological distress in the first survey, but not the second. People living in cities with a population between 100,000 and 500,000 had lower psychological distress compared to residents of cities with a population of more than 500,000 in the first survey, but not the second. Interaction term analysis provides evidence of changes in the underlying relationship between living in a city with a population of 100,000–500,000 and psychological distress between the two surveys (p = 0.084).

COVID-19 disease-specific variables

Participants who reported a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection had higher psychological distress compared to individuals who reported not having contracted the virus. The effect was bigger in the first survey. People who responded that they did not know if they were infected had higher psychological distress compared to individuals who reported not being infected, and there was no significant difference between the two surveys. Having a friend or relative with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 was not statistically significant in either survey. People with a higher perceived risk of getting COVID-19 showed higher psychological distress, with no difference between the two surveys. People at risk of COVID-19 complications due to underlying medical conditions did not have statistically significantly higher distress compared to people without underlying medical conditions in either of the surveys.

Pandemic situation-related variables

Changes in alcohol use (increase or decrease in consumption) were associated with elevated levels of psychological distress among participants in both surveys. The analyses of people’s mental health in connection with their inability to get healthcare services showed a statistically significant increase in psychological distress, although this effect was only marginally significant in Survey 1. The effect of losing a job on psychological distress was significantly positive when estimated for the data in Survey 1, but not in Survey. Also, personal job loss was not significantly associated with psychological distress in the full-sample analysis. Interaction term analysis provided evidence of the change in the underlying relationship between job loss and psychological distress between the two surveys (p = 0.06). Neither being placed on unpaid leave nor working remotely was significantly associated with psychological distress in either of the surveys ().

Table 2. Linear regression analysis of determinants of psychological distress in Survey 1 and Survey 2.

Discussion

Our study aimed to determine what factors were associated with psychological distress during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia. We conducted a cross-sectional, online survey at two different time points to capture psychological distress immediately after the two peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia: in May-June 2020 and January-February 2021. We found that levels of psychological distress were high in both time periods and did not significantly change between the surveys. Our findings confirmed our hypotheses that higher psychological distress was associated with higher levels of perceived risk from infection, as well as being associated with losing one’s job, experiencing problems accessing healthcare, and changing one’s drinking behaviour. We also observed that females, those who live alone, were younger, and have lower income were more likely to experience higher levels of psychological distress.

Although pre-pandemic baseline data from our sample population are not available, we can compare the observed levels of distress with normative data from other countries (Lehmann et al., Citation2023) to see that levels of distress in our sample were substantially higher. There is extensive evidence that the onset of the pandemic was accompanied by an increase in mental health problems around the world compared to the pre-pandemic level (Ettman et al., Citation2020; Killgore et al., Citation2021; McGinty et al., Citation2020; Sønderskov et al., Citation2020; Zinchenko et al., Citation2021; Robinson & Daly, Citation2021). Given the fact that in January-February 2021 psychological distress level was not statistically different from May-June 2021, we can infer that nine months after the start of the pandemic, the level of psychological distress remained high in our sample of the Russian population.

The results of our study indicate that the psychological health impact of COVID-19 was not limited to only short-term increase in mental health problems at the start of the pandemic. While meta-analysis of longitudinal studies (Robinson et al., Citation2022) shows that populational mental health became generally comparable to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2020 [although reduction over time for depression was less pronounced], our research shows that the dynamics of the pandemic, manifested in the rise and fall of the number of cases, may have an impact on mental health: large-scale worsening of the epidemiological situation during late fall and early winter of 2020 again caused an increase in mental health problems. A similar pattern is described for Ireland, with depression and anxiety being the highest at the beginning of the pandemic and reaching the second peak in December 2020 during the second ‘wave’ of the pandemic (Spikol et al., Citation2021).

While the increase in mental health problems at the early stage of the pandemic was documented in previous research in Russia (Zinchenko et al., Citation2021), our research aimed to track temporal changes in mental health and the factors associated with mental health during the pandemic. We looked specifically at how factors associated with psychological distress differed between the two surveys. Having had COVID-19 and high perceived risk of the virus were statistically significant in their association with psychological distress in both surveys. We did find that having a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection had a greater effect on psychological distress at the early stage of the pandemic compared to the sample in the later survey. Our survey results showed that personal job loss during the pandemic had a large and statistically significant effect on psychological distress in the first survey. These findings are similar to research from other settings that showed job loss to be associated with poor mental health (Killgore et al., Citation2021; Mojtahedi et al., Citation2021; Posel et al., Citation2021). However, in our Survey 2, job loss was not statistically significantly associated with psychological distress. This may be because a longer time had passed, as in both survey respondents were asked to indicate job loss since the beginning of the pandemic. It is plausible that respondents were already able to find new employment by the time of the second survey given what is known about the flexibility of the Russian labour market (Gimpelson & Kapeliushnikov, Citation2011).

Since the onset of the pandemic, the number of people who reported problems accessing healthcare increased dramatically. The COVID-19 pandemic put considerable strain on Russia’s healthcare systems. In our May–June 2020 survey, 36% of the sample experienced such problems, which is much higher compared to the estimates for European countries (van Ballegooijen et al., Citation2021). In our January–February 2021 survey, the percentage of people who experienced a change in health service availability increased by 52% and became a significant determinant of psychological distress. Presumably this increase could be because of the cumulative nature of the effect, in that people continued to put off necessary healthcare visits which meant that it was even more of a source of psychological distress several months into the pandemic. The relationship between mental health and access to healthcare can be bidirectional, as elevated levels of anxiety and depression are known to lead to delayed care-seeking behaviour in some medical conditions (Rane et al., Citation2018; Zhu et al., Citation2020). Regardless of causation, the association between accessing healthcare services and psychological distress, especially during a pandemic, is a public health concern.

In our surveys, we found that change in drinking behaviour during the pandemic was associated with increased levels of psychological distress. Notably, this was true for both an increase and a decrease in consumption. These results are similar to those found for stress about becoming ill from COVID-19 in the UK: both drinking more and drinking less were associated with increased levels of stress (Garnett et al., Citation2021). While many studies conclude that the pandemic leads to an increase in alcohol consumption with individuals using alcohol as a strategy to cope with anxiety (Martínez-Cao et al., Citation2021; Mazzarella et al., Citation2022), our findings support the claim that the pandemic effect varies depending on the individuals drinking motives. For the sample of Belgium students, social motives for drinking predict lower consumption, while coping motives predict higher consumption (Bollen et al., Citation2021). The lack of social activities led to reduced drinking opportunities, while feeling of social isolation contributed to higher consumption.

When interpreting our study results, the following limitations must be considered. First, as we rely on convenience samples, our findings cannot be used to estimate the prevalence of psychological distress in the general population in Russia. Snowball recruitment using social media often leads to oversampling of some demographic groups with higher levels of psychological distress, but can also exclude groups most likely in need, such as people with pre-existing mental illness and the elderly (Pierce et al., Citation2020). The second important limitation is the lack of the ability to compare mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic as pre-pandemic baseline data from study respondents are not available. Moreover, the lack of data on psychological well-being among the general Russian population makes it impossible to determine whether or not our study results indicate higher psychological distress during the pandemic compared to the general Russian population in non-pandemic times. Despite these limitations, our study provides important evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has taken its toll on mental health and provides further insight into how different aspects of the pandemic are associated with psychological distress.

Our study results have several important implications for considering how to address the ongoing mental health needs of Russians during this pandemic. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, practical actions to assist groups that experience high psychological distress, especially during periods of deterioration of the epidemiological situation. Evidence from our study can help identify groups that are particularly exposed to psychological distress and need targeted support. Our findings suggest having contracted COVID-19 is an important predictor of psychological distress. Since the proportion of the population who had COVID-19 and recovered is getting bigger, this group requires special attention as deterioration of mental health can be one of the long-term effects of the disease. People who lost their jobs during the pandemic are also at risk of mental health problems. As our results suggest that higher psychological distress level was associated with both increase and decrease in alcohol consumption, targeted alcohol reduction support may be needed for people who use alcohol to cope during the pandemic. Lastly, our results indicate that more attention is needed to ensure that people who have had to delay necessary medical care are linked to care for addressing the psychological distress that accompanies these delays. The literature on mental health policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic emphasise the importance of adaptability and flexibility of community-based care (Goldman et al., Citation2020; McCartan et al., Citation2021; Moreno et al., Citation2020). To a certain degree, increased need for mental health care during the pandemic was compensated by fast-growing private market of online psychological counselling, but it leaves behind the elderly and those with lower income and lower education levels. Considering that these groups tend to be of lower socioeconomic status (people with lower status are at higher risk of losing their job or experiencing problems with access to healthcare), it is essential to address social inequality in mental healthcare provision, identify common barriers, and provide help to at-risk groups.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (20.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (15 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (18.2 KB)Data availability statement

Our de-identified dataset is available upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åslund, A. (2020). Responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 61(4-5), 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1778499

- Bollen, Z., Pabst, A., Creupelandt, C., Fontesse, S., Lannoy, S., Pinon, N., & Maurage, P. (2021). Prior drinking motives predict alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional online survey among Belgian college students. Addictive Behaviors, 115, 106772. Epub 2020 Dec 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106772

- Brailovskaia, J., Cosci, F., Mansueto, G., Miragall, M., Herrero, R., Baños, R. M., … Margraf, J. (2021). The association between depression symptoms, psychological burden caused by COVID-19 and physical activity: An investigation in Germany, Italy, Russia, and Spain. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113596

- Daly, M., & Robinson, E. (2021). Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: Population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. Journal of Affective Disorders, 286, 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054

- Das, A., Singh, P., & Bruckner, T. A. (2022). State lockdown policies, mental health symptoms, and using substances. Addictive Behaviors, 124, 107084. Epub 2021 Aug 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107084

- Ettman, C. K., Abdalla, S. M., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P. M., & Galea, S. (2020). Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

- Garnett, C., Jackson, S., Oldham, M., Brown, J., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2021). Factors associated with drinking behaviour during COVID-19 social distancing and lockdown among adults in the UK. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 219, 108461. Epub 2021 Jan 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108461

- Gimpelson, V., & Kapeliushnikov, R. (2011). Labor market adjustment: Is Russia different? IZA DP No. 5588. Discussion paper series. Institute for the Study of Labor. Bonn. Available at: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/5588/labor-market-adjustment-is-russia-different (Accessed December 4, 2021).

- Goldman, M. L., Druss, B. G., Horvitz-Lennon, M., Norquist, G. S., Kroeger Ptakowski, K., Brinkley, A., Greiner, M., Hayes, H., Hepburn, B., Jorgensen, S., Swartz, M. S., & Dixon, L. B. (2020). Mental health policy in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatric Services, 71(11), 1158–1162. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000219

- Guidotti, E., & Ardia, D. (2020). COVID-19 data hub. Journal of Open Source Software, 5(51), 2376. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02376

- Gunnell, D., Appleby, L., Arensman, E., Hawton, K., John, A., Kapur, N., Khan, M., O'Connor, R. C., Pirkis, J., & COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration (2020). Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 468–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1

- Holmes, E. A., O'Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., … Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L. T., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

- Killgore, W. D. S., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., & Dailey, N. S. (2021). Mental health during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 561898. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.561898

- Kumar, A., & Nayar, K. R. (2021). COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health, 30(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052

- Lehmann, J., Pilz, M. J., Holzner, B., Kemmler, G., & Giesinger, J. M. (2023). General population normative data from seven European countries for the K10 and K6 scales for psychological distress. Scientific reports (In press). https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2741992/v1.

- Martínez-Cao, C., de la Fuente-Tomás, L., Menéndez-Miranda, I., Velasco, Á, Zurrón-Madera, P., García-Álvarez, L., Sáiz, P. A., Garcia-Portilla, M. P., & Bobes, J. (2021). Factors associated with alcohol and tobacco consumption as a coping strategy to deal with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown in Spain. Addictive Behaviors, 121, 107003. Epub 2021 Jun 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107003

- Mazzarella, C., Spina, A., Dallio, M., Gravina, A. G., Romeo, M., DI Mauro, M., Loguercio, C., & Federico, A. (2022). The analysis of alcohol consumption during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Italian lockdown. Minerva Medica, 113(6), 927–935. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4806.21.07354-7.

- McCartan, C., Adell, T., Cameron, J., Davidson, G., Knifton, L., McDaid, S., & Mulholland, C. (2021). A scoping review of international policy responses to mental health recovery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Research Policy and Systems, 19(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00652-3.

- McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H., & Barry, C. L. (2020). Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA, 324(1), 93–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9740

- Mojtahedi, D., Dagnall, N., Denovan, A., Clough, P., Hull, S., Canning, D., Lilley, C., & Papageorgiou, K. A. (2021). The relationship between mental toughness, job loss, and mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 607246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.607246

- Moreno, C., Wykes, T., Galderisi, S., Nordentoft, M., Crossley, N., Jones, N., Cannon, M., Correll, C. U., Byrne, L., Carr, S., Chen, E. Y. H., Gorwood, P., Johnson, S., Kärkkäinen, H., Krystal, J. H., Lee, J., Lieberman, J., López-Jaramillo, C., Männikkö, M., … Arango, C. (2020). How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(9), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

- Nekliudov, N. A., Blyuss, O., Cheung, K. Y., Petrou, L., Genuneit, J., Sushentsev, N., Levadnaya, A., Comberiati, P., Warner, J. O., Tudor-Williams, G., Teufel, M., Greenhawt, M., DunnGalvin, A., & Munblit, D. (2020). Excessive media consumption about COVID-19 is associated with increased state anxiety: Outcomes of a large online survey in Russia. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e20955. https://doi.org/10.2196/20955

- Nemec, J., Maly, I., & Chubarova, T. (2021). Policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and potential outcomes in central and Eastern Europe: Comparing the Czech republic, the Russian federation, and the Slovak republic. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 23(2), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2021.1878884

- Ochnik, D., Rogowska, A. M., Kuśnierz, C., Jakubiak, M., Schütz, A., Held, M. J., … Cuero-Acosta, Y. A. (2021). Mental health prevalence and predictors among university students in nine countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national study. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 18644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97697-3

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017

- Pieh, C., Budimir, S., Humer, E., & Probst, T. (2021). Comparing mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown and 6 months after the lockdown in Austria: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 625973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.625973

- Pierce, M., McManus, S., Jessop, C., John, A., Hotopf, M., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Wessely, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 567–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6

- Posel, D., Oyenubi, A., & Kollamparambil, U. (2021). Job loss and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown: Evidence from South Africa. PloS one, 16(3), e0249352. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249352

- Rane, M. S., Hong, T., Govere, S., Thulare, H., Moosa, M.-Y., Celum, C., & Drain, P. K. (2018). Depression and anxiety as risk factors for delayed care-seeking behavior in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals in South Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 67(9), 1411–1418. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy309

- Robinson, E., & Daly, M. (2021). Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States: Longitudinal evidence from the understanding America study. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 570–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12493

- Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., Daly, M., & Jones, A. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098

- Sanmarchi, F., Golinelli, D., Lenzi, J., Esposito, F., Capodici, A., Reno, C., & Gibertoni, D. (2021). Exploring the gap between excess mortality and COVID-19 deaths in 67 countries. JAMA Network Open, 4(7), e2117359. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17359

- Sønderskov, K. M., Dinesen, P. T., Santini, Z. I., & Østergaard, S. D. (2020). The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 32(4), 226–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2020.15

- Spikol, E., McBride, O., Vallières, F., Butter, S., & Hyland, P. (2021). Tracking the Irish adult population during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A methodological report of the COVID-19 psychological research consortium (C19PRC) study in Ireland. Acta Psychologica, 220, 103416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103416

- Vakulenko, V., Khodachek, I., & Bourmistrov, A. (2020). Ideological and financial spaces of budgetary responses to COVID-19 lockdown strategies: Comparative analysis of Russia and Ukraine. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(5), 865–874. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0110

- van Ballegooijen, H., Goossens, L., Bruin, R. H., Michels, R., & Krol, M. (2021). Concerns, quality of life, access to care and productivity of the general population during the first 8 weeks of the coronavirus lockdown in Belgium and The Netherlands. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06240-7

- Vancea, F., & Apostol, M.-Ş. (2021). Changes in mental health during the COVID-19 crisis in Romania: A repeated cross-section study based on the measurement of subjective perceptions and experiences. Science Progress, 104(2), 003685042110258. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504211025873

- Zhu, L., Tong, Y. X., Xu, X. S., Xiao, A. T., Zhang, Y. J., & Zhang, S. (2020). High level of unmet needs and anxiety are associated with delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(11), 5299–5306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05333-z

- Zinchenko, Y. P., Shaigerova, L. A., Almazova, O. V., Shilko, R. S., Vakhantseva, O. V., Dolgikh, A. G., Veraksa, A. N., & Kalimullin, A. M. (2021). The spread of COVID-19 in Russia: Immediate impact on mental health of university students. Psychological Studies, 66(3), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-021-00610-1