ABSTRACT

Problematic substance use (SU) is a significant issue among LGBTQ+ individuals, but rates of treatment/help-seeking in this population remain low. This review aimed to investigate literature about intersectional stigma of SU and LGBTQ+ identity and its impact on SU help-seeking behaviours in the U.S. Eligible studies from eight-database were included if peer-reviewed, in English, from the U.S., published between 2000 and 2022, focused on SU, stigma, SU help-seeking behaviours, among LGBTQ+ adults. Of 458 search results, 50 underwent full-text review, 12 were included in the final sample. Minority Stress Theory emerged as a relevant theoretical framework. Findings revealed that increased SU as a coping strategy was associated with minority stress. Intersectional stigma negatively impacted SU treatment experience among LGBTQ+ individuals, leading to avoidance of help-seeking or poor treatment outcomes. Patterns of SU and impact of stigma among LGBTQ+ individuals differ, wherein bisexual and transgender individuals reported significantly more treatment barriers and unique stressors. LGBTQ+ individuals reported earlier age of SU onset and were more likely to encounter opportunities for SU. This review highlights the impact of intersectional stigma on SU help-seeking behaviour among LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. Recommendations are provided for future clinical practice, research, and policy to better support LGBTQ+ individuals.

Introduction

Substance misuse and mental health among LGBTQ+ population

Substance use (SU) issues are highly stigmatised and undertreated, especially when compared to other mental and physical problems (Batts et al., Citation2014; SAMHSA, Citation2015; Yang et al., Citation2017). However, there is a substantial treatment gap between individuals that perceive a need for SU treatment and those who receive treatment in a formal treatment setting in the United States (U.S.) (Wang et al., Citation2007), particularly among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning or otherwise gender or sexuality minority (LGBTQ+) individuals (McCabe et al., Citation2013; Schuler et al., Citation2018). The lack of LGBTQ+ individuals seeking treatment for SU in the U.S. suggests a deficit in traditional health care services for this population.

Prior studies have consistently shown that LGBTQ+ individuals have higher rates of risky SU and greater severity of substance use disorders (SUDs) compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Arterberry et al., Citation2019; Coulter et al., Citation2015; Drabble et al., Citation2013; Operario et al., Citation2014). Moreover, SU patterns vary significantly among LGBTQ+ individuals (Boyd et al., Citation2019; McCabe et al., Citation2019; Schuler et al., Citation2019) where bisexual women exhibit elevated rates of risky SU compared to heterosexual or lesbian women (Demant et al., Citation2018; Schuler et al., Citation2018) and bisexual men and women are associated with greater odds of lifetime use for cannabis, cocaine, inhalants and hallucinogens compared to their same-gendered, heterosexual counterparts (Demant et al., Citation2018). Additionally, SU disparities were highest among younger lesbian women and older bisexual individuals, when compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Schuler et al., Citation2019). These data underscore the need for understanding SU treatment utilisation and experiences within the LGBTQ+ population. One possible influence on help-seeking and treatment utilisation could be stigma about SU and one’s gender/sexual identity.

Stigma and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community

Stigma refers to the devaluation of someone’s identity as less than others through social norms (Corrigan, Citation1998; Goffman, Citation1963), which may undermine one’s health through social exclusion, lessen one’s self-efficacy to cope positively, exacerbate existing mental health symptoms (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2013; Hendricks & Testa, Citation2012; Kuyper & Bos, Citation2016; Reisner et al., Citation2015). Stigma may exist individually, interpersonally, and structurally, demonstrated by impacts of stress on individuals (White Hughto et al., Citation2015).

Individually and interpersonally, stigma against LGBTQ+ individuals may contribute to numerous negative SU and SUD treatment outcomes, including negative stereotyping of oneself, delaying/avoiding initiation of services, early termination of SUD treatment, or treatment approaches aimed towards heterosexual individuals that do not meet their treatment needs (Kelly & Westerhoff, Citation2010; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Kulesza et al., Citation2013; Luoma et al., Citation2012; Pachankis et al., Citation2020; Phillips et al., Citation2020; Reisner et al., Citation2015; Smith et al., Citation2016). Structurally, stigma exists multidimensionally across overlapping identities and in treatment for SUDs. Racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+, and individuals who hold multiple minority identities and have historically faced stigma and discrimination may experience additional challenges (e.g. oppression/racism in the LGBTQ+ community, heterosexism within communities of colour) resulting to be targeted simultaneously in sexist, racist, and homo/bi/trans-phobic discrimination (Balsam et al., Citation2013; Bowleg et al., Citation2003; Bridges et al., Citation2003; Chae et al., Citation2010; Giwa & Greensmith, Citation2012; Han, Citation2007; Pauly et al., Citation2016; Radcliffe & Stevens, Citation2008). The intersection of being a gender or sexuality minority (GSM) and having SU issues, two highly stigmatised groups, creates compounding barriers for LGBTQ+ individuals to access and successfully complete treatment for SU and SUDs (Benz et al., Citation2019; Luoma et al., Citation2012; Smith et al., Citation2016).

Additionally, discrimination and harassment are major challenges faced by LGBTQ+ community. Such experiences are associated with higher rates of anxiety, depression, stress, and SU as a coping mechanism (Casey et al., Citation2019; Ngamake et al., Citation2016; Ortiz-Hernández et al., Citation2009). For example, prior evidence examined the prevalence of hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among GSM adults in the U.S. and found a significant proportion of LGTBQ+ individuals experienced harassment, discrimination, and violence due to their GSM identity which negatively impacted their mental and physical health (Herek, Citation2009). These challenges can be amplified for transgender individuals, who may delay or avoid treatment due to discrimination against their gender identity and SU behaviours within healthcare settings and further exacerbate SU to cope with identity-related stressors (Clements-Nolle et al., Citation2001; Felner et al., Citation2020; Kattari et al., Citation2020; Powell et al., Citation2011; Reisner et al., Citation2015).

Minority stress theory & resilience

Minority Stress Theory (MST; Meyer, Citation2003) is a widely used theoretical framework that explains the relationship between identity-based stigma, mental health, and well-being among LGBTQ+ individuals (Lefevor et al., Citation2019; Tebbe & Moradi, Citation2016). MST has been instrumental in exploring the unique experiences of stress and adversity faced by LGBTQ+ individuals with regards to health and SUD treatment utilisation (Alessi, Citation2014; McConnell et al., Citation2018). Although stigma, discrimination, and other forms of minority stress are major challenges in the LGBTQ+ community, it is important to note that resilience has been identified as an important protective factor against sexual minority stressors, stigma, and discrimination (Kosciw et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2020).

Resilience, a strengths-based framework, examines one’s ability to persist and thrive during significant stressors (Knight et al., Citation2022; Masten, Citation2001). Particularly, LGBTQ+ individuals may find sources of resilience and strength to navigate minority stress in taking pride in their identity (e.g. who they are), creating chosen families who offer support/care beyond the traditional family structures, and connecting to others in the LGBTQ+ community for a sense of belonging (Bourguignon et al., Citation2020; Colpitts & Gahagan, Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2020). While challenges still exist, recognising and building resilience are critical for LGBTQ+ community.

Substance use treatment utilization & help-Seeking behaviors

Literature on SU help-seeking behaviours among LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. identified two themes that can impact their well-being: treatment utilisation and treatment experience (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Clements-Nolle et al., Citation2001; Felner et al., Citation2020; McCabe et al., Citation2013; Reisner et al., Citation2015). For example, LGBTQ+ individuals who expect discriminatory treatment (anticipated/expected stigma) and unfriendly experience from healthcare professionals (e.g. structural stigma) are more likely to avoid seeking services, which may in turn lead to SU to cope with distress (Ashford et al., Citation2019; Bradford et al., Citation2013; Meyer, Citation2003; Reisner et al., Citation2015; SAMHSA, Citation2019; Seelman et al., Citation2017). Moreover, even if treatment is initiated, individuals who experience discrimination and harassment while in treatment have poorer treatment outcomes, lower odds of initiating services in the future, and less comfort with healthcare providers (Bradford et al., Citation2013; Seelman et al., Citation2017; Smalley et al., Citation2015). The lack of identity-affirming treatment within SU treatment for LGBTQ+ clients highlights the need to examine current treatment experiences, and adapt interventions for LGBTQ+ populations that go beyond only identifying barriers within treatment.

Study aim & significance

It is critical that the SU treatment and research profession address the impact of intersectional stigma on help-seeking behaviours among LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. in order to facilitate better intervention efforts in this at-risk population. To avoid perpetuating ignorance and harm towards LGBTQ+ individuals with SUDs and co-occurring disorders, a better understanding of the influences of intersectional stigma on help-seeking behaviours is an important step towards addressing this challenge. However, current research exploring relationships between stigma, treatment experience, and health outcomes among LGBTQ+ people in the U.S. has focused primarily on minority identity rather than considering the intersections of multiple stigmatised identities (e.g. minority status and a person with a SU behaviour).

To contribute to this gap, this scoping review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of intersectional stigma on SU treatment utilisation and help-seeking experiences within the LGBTQ+ community in the U.S. treatment or study settings by reviewing and evaluating peer-reviewed English literature published between 2000 and 2022 focused on SU, stigma, SU help-seeking behaviours, among LGBTQ+ adults in the U.S. This review intends to identify research, policy, and practice directions that could improve the health outcomes in this population in the U.S.

Methods

Search strategy and information sources

This scoping review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018) and managed through Covidence systematic review software to ensure accuracy and efficiency. Three search strategies were used: (1) electronic database searching; (2) reference harvesting; and (3) grey literature searching. To identify potentially relevant documents, eight bibliographic databases and Google Scholar were searched. Details regarding used databases and combination of keywords, see Supplementary Table S1. This scoping review does not involve direct interaction with human subjects or the collection of new data. Therefore, it does not require Institutional Review Board review and approval. This scoping review does not have a registered review protocol, which is a requirement for systematic reviews.

Eligibility criteria & study selection

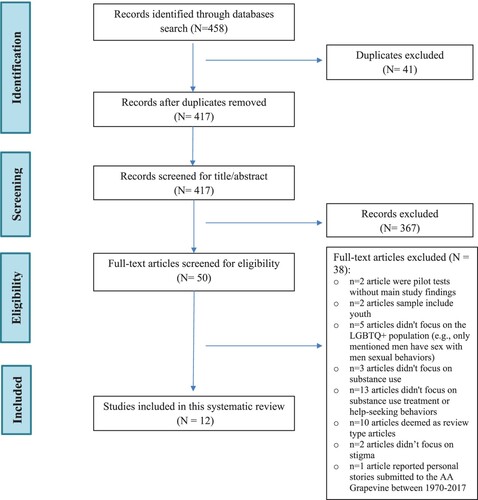

A comprehensive review of these databases was conducted (date of last search: March 10, 2023) to identify up-to-date eligible studies if: (a) published between 2000 and 2022; (b) written in English language; (c) peer-reviewed; (d) focused on SU, stigma, SU help-seeking behaviours, and identify as LGBTQ+ populations; (e) sample of the participants are adults; (f) had a treatment or study setting in the U.S. Using the search strategies listed above, the initial literature search generated from eight databases a total of 458 studies. After removing duplicates (n = 41), 417 were left for title and abstract review. Two independent reviewers (YX, MRW) screened all 417 articles separately, n = 367 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The title and abstract review produced 50 records deemed relevant and eligible for full-text review, 12 were included in this scoping review after full-text review (inclusion criteria see ).

Table 1. Inclusion criteria.

Data extraction/charting and synthesis

Each included study was reviewed to extract descriptive information on demographic information and study participant characteristics (e.g. sample size, age, race, LGBTQ+ identity, SU type, age of onset of SU, SU treatment utilisation), design features (e.g. qualitative or quantitative study design, underlying theories and frameworks, study participant recruitment strategies), definitions and types of stigma, identified protective factors for health, outcome measured using measurements, overall findings on the impacts of intersectional stigma on LGBTQ+ community, and suggested implications for future research, practice, and policy. For each article, details were extracted and recorded into a standard Excel data extraction worksheet that has been previously tested and proven to be reliable in prior scoping reviews. Two reviewers (YX, CMS) independently extracted data into the worksheet and met to discuss and clarify the content included in the worksheet. To synthesise data, all the reviewers conducted an iterative review process of included studies to identify commonalities and discrepancies in the main results, conclusions, and implications that characterise the complex concept of intersectionality of stigma and SU among LGBTQ+ individuals seeking treatment in the U.S. All co-authors examined the data extracted from each article after reviewing all studies to approve the current evidence.

Methodological quality assessment

To improve rigour and reliability of our scoping review findings, we selected a 16-item quality assessment tool, Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD; Sirriyeh et al., Citation2012) for quality assessment (more details of QATSDD see Supplementary Material). Our included twelve articles were assessed independently by raters to evaluate their quality and methodological characteristics. Each article was scored on a scale from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Complete) for each quality characteristic, where higher scores indicated better quality (Sirriyeh et al., Citation2012). Two raters (YX, MRW) independently reviewed the same full-text and analysed the quality of articles by following the QATSDD steps (Sirriyeh et al., Citation2012). A third independent rater (CMS) was involved in the quality coding process without any prior exposure to the quality assessment coding process to resolve any major score discrepancies between the two original raters. Group discussion was also used to resolve any discrepancies to improve findings’ validity and inter-rater reliability. Our rated articles’ final scores ranged 23–35 points. Results of quality assessment are presented in .

Table 2. Summary of articles quality assessment.

Results

Study selection outcome

A total of 12 studies were included: three qualitative studies (Felner et al., Citation2020; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Penn et al., Citation2013) and nine quantitative studies (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Benz et al., Citation2019; Cochran et al., Citation2007; Green, Citation2011; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2020; Lukowski et al., Citation2016; Operario et al., Citation2014; Reisner et al., Citation2015). A summary of the study selection process is demonstrated in .

Age, sexual and gender identities, ethnicity, and other demographic information

All studies were conducted in the U.S. The sample size varied substantially (from 10–169,883). The ages of participants ranged from 18 to 96 (Mean Age is approximately 33). Target groups’ sexual and gender identities also varied between gay (67%), bisexual (67%), lesbian (58%), transgender (58%), queer or non-binary (33%), and GSM (8%). The majority of study participants were White/Caucasian, with small numbers of Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black/African American, and Native American represented in the selected articles. Most study participants had GED/high-school or some college/tech-school education background, never married/being single, and reported an annual household income of more than $30, 000. Four studies mentioned some of their participants had completed sex reassignment/gender-affirming surgery (Kidd et al., Citation2019; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Operario et al., Citation2014; Reisner et al., Citation2015). For more details of study participant characteristics, see .

Table 3. Study participant characteristics.

Study participant recruitment

A combination of community outreach strategies was employed in included studies to recruit participants, including advertisements/flyers on LGBTQ+ related websites/listservs/social media and community organisations, participant referral, purposive venue-based outreach, healthcare clinics, cooperated with key informants within existing projects and centres, and using data from national surveys. More information of study participant recruitment strategies, see supplemental document.

Underlying theories and frameworks mentioned in the articles

Eight included articles discussed MST (Meyer, Citation2003) as their theoretical framework (Benz et al., Citation2019; Cochran et al., Citation2007; Felner et al., Citation2020; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2020; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Operario et al., Citation2014; Reisner et al., Citation2015) and four articles did not report theories as part of their study design (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Green, Citation2011; Lukowski et al., Citation2016; Penn et al., Citation2013). Another four theories and frameworks were also mentioned in the included articles, including the intersectionality framework (Benz et al., Citation2019; Else-Quest & Hyde, Citation2016a, Citation2016b), the syndemic framework (Operario et al., Citation2014; Singer & Clair, Citation2003), the grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; Matsuzaka, Citation2018), and the health equity promotion model (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2020). Descriptions of these theories, see Supplementary Table S2.

Study research measures

Demographics, identities, self-reported SU-related outcomes, psychological conditions, treatment history/barriers, community participation, and intention for help-seeking were explored via measures in studies. Details of study research measures, see Supplementary Material.

Substance use type and age of onset of substance use

Half of the studies (n = 6) used the general term ‘alcohol and drug use’ or ‘substance use’ not otherwise specified, and the remaining studies focused on alcohol use (33%) (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Green, Citation2011; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Matsuzaka, Citation2018) and tobacco smoking (17%) (Lee et al., Citation2020; Lukowski et al., Citation2016). There were only two articles out of twelve examined the age of onset of SU (Felner et al., Citation2020; Lukowski et al., Citation2016), finding that over half of participants (62.8%, n = 4,795) reported they began smoking between ages 13 and 18 years, nearly one fifth (18.4%, n = 1,406) reported onset of smoking <13 years, 16.9% (n = 1,289) reported onset between 19 and 30 years, and only 1.9% (n = 148) reported onset between 31 and 55 years. There was a slightly but statistically significant earlier age of smoking onset in the LGBTQ group (mean = 16.1 years) than the heterosexual group (mean = 16.7 years) (t = 9.53, p < .001) (Lukowski et al., Citation2016).

Substance use treatment utilization

All of the articles explored past SU help-seeking behaviours or treatment experiences, whereas seven articles examined professional SU treatment utilisation (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Benz et al., Citation2019; Felner et al., Citation2020; Green, Citation2011; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Lukowski et al., Citation2016; Penn et al., Citation2013). Due to the limited space, details of SU treatment utilisation were presented in Supplementary Material.

Definitions of stigma

Among these included articles, stigma was primarily described as a negative attitude or disapproval attached to characteristics of an individual, and was closely related to unfair discrimination, prejudice, and exclusion. Only two studies (Benz et al., Citation2019; Matsuzaka, Citation2018) contained a specific definition of stigma in their articles. In these two studies, stigma was referred to as an attribute that is deeply discrediting a usual person to a discounted and marginalised one (Benz et al., Citation2019; Goffman, Citation1963); it could also be understood as a social process/dynamic within social-cultural, economic, and political context to limit resources, opportunities, and well-being of people by labelling a specific group (Link & Phelan, Citation2001; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Poteat et al., Citation2013).

Types of stigma

In most of the articles, stigma was generally summarised as GSM identity-related stigma, such as anti-gay stigma (Cochran et al., Citation2007), transgender-related stigma (Operario et al., Citation2014), or SU-related stigma (Penn et al., Citation2013) without further discussing its various forms. In five of the reviewed studies (Benz et al., Citation2019; Felner et al., Citation2020; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Reisner et al., Citation2015), multi-level stigma was explored by discussing its subtypes (e.g. enacted stigma, anticipated/expected stigma, internalised stigma, interpersonal stigma, structural stigma) and examined using standardised measures or questions. Details of subtypes of stigma and stigma measures, see .

Table 4. Subtypes of stigma.

Protective factors for health

Half of the studies (n = 6) explored and discussed potential protective factors for health (Cochran et al., Citation2007; Felner et al., Citation2020; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2020; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Reisner et al., Citation2015), including being White/Non-Hispanic, being in the high-income bracket, having a college degree, having private insurance, having undergone surgical gender affirmation or joining affirming programmes (e.g. Gay-Straight Alliances), having had identity integration/sexual-orientation disclosure to friends/family members, and utilising universal resilience (e.g. advertising skepticism and having people to talk about being a GSM) could be potential protective factors for health.

Summary of findings

Overall, the study findings revealed that SU treatment barriers are more common for LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. due to the intersections of minority identities-related stigma (e.g. GSM, drug use minority behaviour, ethnicity minority). However, findings from Green’s (Citation2011) and Cochran et al.’s (Citation2007) studies suggested that GSM individuals did not endorse higher levels of SU severity compared to heterosexual individuals, which was inconsistent with other research findings (e.g. Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Benz et al., Citation2019). Moreover, bisexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming (TGNC) individuals among LGBTQ+ populations reported significantly more treatment barriers and unique stressors (e.g. patterns of SU, sexual risk behaviours, stigma associated with coming out) (Finlayson et al., Citation2011; Flentje et al., Citation2015; Lee, Citation2015; Reback et al., Citation2014), and lower odds of improvement in treatment outcome than heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016; Felner et al., Citation2020; Kidd et al., Citation2019; Reisner et al., Citation2015).

Secondly, stigma related to SU and having been refused treatment in the past due to GSM identity (enacted stigma) were significantly associated with avoidance of help-seeking for healthcare and delayed or declined medical care when sick/injured or routine prevention care (anticipated stigma) compared to heterosexual individuals (Benz et al., Citation2019; Reisner et al., Citation2015). Higher levels of enacted SU stigma predicted a higher likelihood of having sought help in the past while a higher level of felt/internalised stigma was associated with a higher likelihood of improvement (Benz et al., Citation2019). These findings were consistent with existing research (e.g. Hatzenbuehler, Citation2009) which highlights the negative impact of stigma on stress and help-seeking behaviours among LGBTQ+ individuals, while inconsistent with some studies who found LGB individuals were more likely to utilise service for SU problems (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016).

Thirdly, increased SU has been used as a coping strategy due to gender and sexuality minority stress (e.g. fear of being discriminated against during treatment; worried about being an outsider of the community; to suppress awareness, cognition and feelings related to gender identity) (Felner et al., Citation2020; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Operario et al., Citation2014; Reisner et al., Citation2015). A greater level of enacted stigma by providers was associated with a higher level of self-reported SU to cope, and delays in both needed and preventive care (anticipated stigma) was highly related to increased SU which attenuated the effect of enacted stigma (Reisner et al., Citation2015). Additionally, sociocultural influences (e.g. gathering in gay bars) may increase the availability of SU to cope with interpersonal stressors (e.g. ‘being an outsider’) (Felner et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, when it related to mental health, GSM individuals reported higher rates of mental health issues (e.g. anxiety, depression, isolation/loneliness, low self-esteem, suicidal thoughts and attempts) compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Cochran et al., Citation2007; Lukowski et al., Citation2016; Penn et al., Citation2013), which further negatively impact their ability to successfully change substance misuse (Lukowski et al., Citation2016). More specifically, gay or bisexual men were more likely than heterosexual men to report a recent suicide attempt, and lesbian or bisexual women were more likely than heterosexual women to show evidence of depressive disorders (Cochran et al., Citation2007).

Furthermore, study findings highlighted that increased enacted stigma on GSM identity (e.g. others’ homophobic and transphobic comments/attitudes, being sexually assaulted and/or socially isolated in the treatment facility) was directly associated with lower improved treatment outcome, greater risk for overlapping health challenges, or early termination of SUD treatment (Kidd et al., Citation2019; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Operario et al., Citation2014). In contrast, those who shared positive and holistic treatment experiences and who remained in the treatment programme, reported feeling respected and accepted by facility staff and other clients (Penn et al., Citation2013). These positive experiences helped participants integrate their identity into their treatment goals, leading to more beneficial and effective treatment experiences (Penn et al., Citation2013).

Lastly, LGBTQ+ individuals reported an earlier age of onset of using substances, suggesting they may be more vulnerable to developing SUDs at a younger age than heterosexual individuals (Lukowski et al., Citation2016). Additionally, study findings showed that LGBTQ+ individuals were more likely to report living with or hanging out with another substance user and being surrounded by SU-oriented occasions (e.g. drag show, pride parade) than heterosexual individuals, which may increase their risk of exposure to SU environments and hinder their ability to maintain sobriety (Lee et al., Citation2020; Lukowski et al., Citation2016). A summary of clinical findings, see .

Table 5. Summary of clinical findings of the scoping review.

Discussion

This scoping review discovered discrepancies and inconsistencies in research findings between studies regarding the impact of stigma on SU help-seeking behaviours among LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. While most studies suggested that LGBTQ+ individuals reported higher levels of SU and higher severity rates on SUDs than heterosexual individuals, some studies found GSM individuals do not have higher levels of SU severity compared to heterosexual individuals. Moreover, enacted stigma and anticipated stigma were found to be significantly associated with avoidance of help-seeking and delayed or declined medical care in most studies, while some studies indicated that LGB individuals were more likely to utilise SU treatment services. These discrepancies in findings may be attributed to various reasons, such as the differences in sampling strategies, the different layers and diverse intersectional minority identities, the difference of research settings, or the various of measures that used to assess SU severity and consequences in the studies (e.g. use well-established measures or DSM diagnostic criteria VS. study teams’ self-developed questions). Furthermore, our review suggested bisexual and TGNC individuals reported significantly more treatment barriers and unique stressors and lower odds of improvement in treatment outcome than heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals (Allen & Mowbray, Citation2016), which may have contributed to these discrepancies. However, the discrepancy on utilisation of SU services among LGBTQ+ individuals also suggested the observed impact of stigma on help-seeking behaviours may not be universal across all GSM groups and/or all treatment or healthcare sectors (e.g. inpatient, outpatient, community-based healthcare), indicating an important research area for future study.

In conclusion, these discrepancies and inconsistencies in research findings underscored the need for additional study to better understand the complex intersections of GSM identities, SU patterns, and treatment barriers experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. These findings also highlighted the significance of providing culturally competent and affirming care that could address the unique challenges and stigma faced by LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S.

Diversity & inclusion in substance use among LGBTQ+ studies

This review examined demographic characteristics of participants in the included studies, with substantially varied sample size ranging from 10 to 169,883. The findings suggested the review’s sample populations were diverse in terms of age, sexual and gender identities, ethnicity, and other demographic information (e.g. education, household income, relationship).

However, all the studies have a treatment or study setting in the U.S., and the data seems skewed towards those being White/Caucasian, single/never married, had GED or college education background, and with a middle-to-high income level, which may limit the generalizability of the overall findings of the review to a more diverse and global population both within the U.S. and in other countries. Therefore, it is critical that future research recruit more representative samples from varying countries, educational backgrounds, income levels, and relationship situations to ensure the relevance of these findings across a wider range of individuals and contexts. Additionally, future research should consider including more racial and ethnic minorities (e.g. Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) individuals) and people who have disabilities in their study to improve the diversity and generalizability of the findings to those with intersectional identities. Indeed, the various demographic characteristics of sample populations may play a role in the findings, which should be taken into account when interpreting and generalising the findings to other populations to avoid potential biases.

Implications for clinical practice

This scoping review recommended that professionals should engage in continued education/training to remain informed of current research findings and LGBTQ+ rights-related policies to better provide psychoeducation to LGBTQ+ clients, particularly TGNC clients, regarding the risks and benefits of participating in peer support groups (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous) for recovery and gender transitions. Moreover, professionals should acknowledge the potential risks, microaggressions, harassment, and biases/prejudices against LGBTQ+ communities within treatment settings and take a more open stance in implementing appropriate solutions for a better treatment setting and an LGBTQ+ affirming space (e.g. gender-neutral restrooms).

Additionally, because LGBTQ+ youth initiate SU at a younger age than their heterosexual counterparts, professionals who work with young adults or youth in particular should give special consideration on exploring the process of ‘coming out’ both outside and within the therapeutic context and in relation to their SU behaviours. Healthcare professionals should also inquire about individuals’ barriers to receive treatment and past treatment experiences once in treatment (e.g. gender dysphoria) to gain a better understanding of the treatment process and client’s desired treatment outcomes.

Notably, the findings suggested that healthcare professionals should utilise diagnostic interviewing or motivational interviewing techniques and integrate two key themes from the research into their daily practice with the LGBTQ+ population: the pink elephant in the room (‘the role of sexual identity in therapy’), and searching for an authentic and holistic approach in treatment for clients to freely discuss their minority identities and how it intersects with their mental health, SU, or other issues to understand their unique experiences and tailor the treatment plans to meet their specific needs.

Furthermore, the continuity of care between primary health care providers and therapists in supporting LGBTQ+individuals’ mental health and physical well-being, was also a notable finding from this review. Healthcare professionals should also consider the role of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and exposure to SU-oriented social environments in the treatment, which may be beneficial to understand these GSM individual’s relationship with substances, mental health disorders, and psychosocial distress (e.g. discrimination and harassment). Lastly, findings revealed that discussing current social support networks and the role of SU in social interactions is crucial for a better treatment outcome.

Overall, these implications on clinical practice emphasised the importance of providing individualised, inclusive, culturally humble (e.g. tailed treatment plants for BIPOC communities), and LGBTQ+ affirming care for GSM individuals seeking SU treatment to optimise treatment outcomes. A summary of implications for clinical practice, see .

Table 6. Implications for clinical practice, research, and policy.

Implications for research

Our comprehensive review findings, primarily focused on the U.S., have profound implications for supporting and tailoring future research funding strategies in the topic of LGBTQ+ and SU treatment to foster a more globally inclusive and diverse approach to understanding the complex intersectionality of stigma, SU, help-seeking behaviours, treatment disparities and needs among LGBTQ+ individuals in the U.S. This review suggested that future research should consider exploring the relationships between minority stress, identity development, and SU treatment utilisation longitudinally with larger samples from diverse backgrounds or leverage national datasets to better understand how intersectional stigma could long-term impact LGBTQ+ individuals’ SU and coping under minority stressors. It is important for future studies to help identify the ‘best timing’ and duration for interventions to reduce stigma, promote culturally tailored therapeutic interventions, and improve SU treatment outcomes for LGBTQ+ individuals.

Secondly, there is a need to investigate how the intersections of multiple minority identities (e.g. race, gender, sexuality, SU behaviours) may affect SU treatment outcomes. Especially, researchers should consider exploring SU treatment utilisation and treatment barriers among bisexual and transgender individuals within the LGBTQ+ communities, where stigma may not uniformly be associated with treatment utilisation across all LGBTQ+ subgroups. This review also highlighted that future research should consider conceptualising SU stigma as both a barrier and motivator in SU treatment, which may inform future treatment interventions to better serve those gender and sexuality minorities with SUDs and co-occurring disorders.

Further, research should consider exploring interventions that could promote greater inclusivity through the removal of procedures that marginalise GSM individuals (e.g. update screening and assessment forms). Additionally, future researchers should consider developing effective interventions (e.g. use inclusive languages) and innovative research designs (e.g. use photovoice, virtual reality simulations, collaborate with LGBTQ+ community members) to reduce stigma and increase access to culturally competent SU treatment to better serve LGBTQ+ individuals.

Moreover, future research should include discussions on positive experiences/factors that contribute to successful outcomes (e.g. universal resilience). As many studies have explored and discussed treatment barriers, identifying protective factors and their influences on positive outcomes could promote better practices in treatment and may potentially transform future training programmes’ development for healthcare professionals. Lastly, review findings also revealed that both clients and therapists may prefer to be matched based on similar identities which suggests an important area that could help identify potential motivations for client-therapist matching and influences on treatment outcomes. A summary of implications for research, see .

Implications for policy

This review suggested that policy makers should allocate attention to creating and supporting substance-free social environments to promote health and well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals by providing more funding to programmes recognise biases towards LGBTQ+ communities and address LGBTQ+ cultural competence topics. Supporting these programmes (e.g. sports, festivals, events that do not involve SU) will help enhance people’s awareness of social biases towards this minority group, foster a sense of community belonging, and reduce their minority stress.

Secondly, policy makers should consider implementing educational campaigns that promote public understanding of GSM identities. Clinical professional practice boards/organisations should provide regular free-of-charge training opportunities to healthcare professionals and organisations in order to improve their care for LGBTQ+ communities. Regulations that require this specialised training should be utilised as part of their licensure renewal requirements and government funding support. Moreover, policy makers should consider modifying their current polices to reduce stigma towards LGBTQ+ individuals and implement anti-discrimination laws to protect them from discrimination and unfair treatment in employment, housing, and public accommodations.

Additionally, policy makers should increase funding opportunities for research projects that explore the intersectional stigma on SU treatment among LGBTQ+ communities, which can help to build effective interventions and preventions of SUDs in this populations. In turn, government-funded research projects findings could be used to inform policy developments to address unique needs and challenges that LGTBQ+ faced in SU treatment. Furthermore, policy makers should consider utilising their power and influence to promote healthy behaviours through public advertisements (e.g. radio, billboards) to reduce cultural acceptance of SU and encourage mental health and SU treatment. Lastly, policy makers should consider improving current public insurance benefits coverage to allow more individuals who depend on public insurance (e.g. Medicaid, Medicare) to promote equitable access to SU treatment without increased financial burdens. A summary of implications for policy, see .

Limitations

Although this review has many strengths, it has limitations that should be considered. First, to be considered and included in this scoping review, articles must be published in a peer-reviewed journal and indexed in the eight databases that authors searched for this review. This limited search scope may lead to the overlook of some articles that was not able to have a chance for publications, especially those with non-significant findings which tend to be less published. As a result, the research team may not capture all relevant research studies on the topic.

Second, studies included in this scoping review must be published in English and have a study or treatment setting in the U.S. in order to be analysed for this review, which may result in a miss of valuable literature published in other languages or conducted outside of the U.S. Additionally, even though the authors conducted a quality assessment using QATSDD, this quality assessment tool heavily relies on the competency and expertise of each reviewer in evaluating all quality characteristics to enable fair and consistent assessment, which may vary within the study team. Lastly, findings from this scoping review may not be generalised to all LGBTQ+ individuals as our twelve included articles vary in their focused populations which may not apply to some specific subgroups.

Conclusion

Our scoping review provided a comprehensive analysis on the topic by looking at existing literature and provided suggestions on implications within the U.S. It is essential to acknowledge that the impact of intersectional stigma on SU treatment among LGTBQ+ individuals is a complex and important topic that requires attention from professionals, researchers, and policy makers to better understand the phenomenon and to develop effective interventions to reduce stigma and enhance treatment outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to Dr. Cecilia Mengo for providing feedback to improve the quality of this manuscript. Authors’ Contributions: YX and AKD designed and conceptualised the study topic. YX and MRW conducted article screening and quality assessment. YX and CMS summarised content into tables. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alessi, E. J. (2014). A framework for incorporating minority stress theory into treatment with sexual minority clients. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2013.789811

- Allen, J. L., & Mowbray, O. (2016). Sexual orientation, treatment utilization, and barriers for alcohol related problems: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161, 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.025

- Arterberry, B. J., Davis, A. K., Walton, M. A., Bonar, E. E., Cunningham, R. M., & Blow, F. C. (2019). Predictors of empirically derived substance use patterns among sexual minority groups presenting at an emergency department. Addictive Behaviors, 96, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.021

- Ashford, R. D., Brown, A. M., & Curtis, B. (2019). The language of substance use and recovery: Novel use of the Go/No-Go association task to measure implicit bias. Health Communication, 34(11), 1296–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1481709

- Balsam, K. F., Beadnell, B., & Molina, Y. (2013). The daily heterosexist experiences questionnaire: Measuring minority stress among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 46(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175612449743

- Batts, K., Pemberton, M., Bose, J., Weimer, B., Henderson, L., Penne, M., Gfroerer, J., Trunzo, D., & Strashny, A. (2014). Comparing and evaluating substance use treatment utilization estimates from the national survey on drug use and health and other data sources. In CBHSQ data review (pp. 1–120). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

- Benz, M. B., Palm Reed, K., & Bishop, L. S. (2019). Stigma and help-seeking: The interplay of substance use and gender and sexual minority identity. Addictive Behaviors, 97, 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.023

- Bourguignon, D., Teixeira, C. P., Koc, Y., Outten, H. R., Faniko, K., & Schmitt, M. T. (2020). On the protective role of identification with a stigmatized identity: Promoting engagement and discouraging disengagement coping strategies. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(6), 1125–1142. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2703

- Bowleg, L., Huang, J., Brooks, K., Black, A., & Burkholder, G. (2003). Triple jeopardy and beyond: Multiple minority stress and resilience among black lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7(4), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1300/J155v07n04_06

- Boyd, C. J., Veliz, P. T., Stephenson, R., Hughes, T. L., & McCabe, S. E. (2019). Severity of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders among sexual minority individuals and their “not sure” counterparts. LGBT Health, 6(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0122

- Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J. A., & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796

- Bridges, S. K., Selvidge, M. M. D., & Matthews, C. R. (2003). Lesbian women of color: Therapeutic issues and challenges. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 31(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2003.tb00537.x

- Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research, 54(Suppl 2), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229

- Chae, D. H., Krieger, N., Bennett, G. G., Lindsey, J. C., Stoddard, A. M., & Barbeau, E. M. (2010). Implications of discrimination based on sexuality, gender, and race/ethnicity for psychological distress among working-class sexual minorities: The United for Health Study, 2003–2004. International Journal of Health Services, 40(4), 589–608. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.40.4.b

- Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., Guzman, R., & Katz, M. (2001). HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: Implications for public health intervention. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 915–921. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.6.915

- Cochran, S. D., Mays, V. M., Alegria, M., Ortega, A. N., & Takeuchi, D. (2007). Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.785

- Colpitts, E., & Gahagan, J. (2016). The utility of resilience as a conceptual framework for understanding and measuring LGBTQ health. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0349-1

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- Corrigan, P. W. (1998). The impact of stigma on severe mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 5(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(98)80006-0

- Coulter, R. W., Blosnich, J. R., Bukowski, L. A., Herrick, A. L., Siconolfi, D. E., & Stall, R. D. (2015). Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems between transgender- and nontransgender-identified young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.006

- Demant, D., Hides, L., White, K. M., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2018). Effects of participation in and connectedness to the LGBT community on substance use involvement of sexual minority young people. Addictive Behaviors, 81, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.028

- Drabble, L., Trocki, K. F., Hughes, T. L., Korcha, R. A., & Lown, A. E. (2013). Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 639–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031486

- Else-Quest, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2016a). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. Theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316629797

- Else-Quest, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2016b). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: II. Methods and techniques. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316647953

- Felner, J. K., Wisdom, J. P., Williams, T., Katuska, L., Haley, S. J., Jun, H. J., & Corliss, H. L. (2020). Stress, coping, and context: Examining substance use among LGBTQ young adults with probable substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 71(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900029

- Finlayson, T. J., Le, B., Smith, A., Bowles, K., Cribbin, M., Miles, I., Oster, A. M., Martin, T., Edwards, A., Dinenno, E., & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011). HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. cities, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 60(14), 1–34.

- Flentje, A., Heck, N. C., & Sorensen, J. L. (2015). Substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients entering substance abuse treatment: Comparisons to heterosexual clients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(2), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038724

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Simoni, J. M., Kim, H. J., Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., Yang, J., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., & Muraco, A. (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000030

- Giwa, S., & Greensmith, C. (2012). Race relations and racism in the LGBTQ community of Toronto: Perceptions of gay and queer social service providers of color. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(2), 149–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.648877

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

- Green, K. E. (2011). Barriers and treatment preferences reported by worried drinkers of various sexual orientations. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2011.538311

- Han, C. (2007). They don't want to cruise your type: Gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities, 13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630601163379

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

- Herek, G. M. (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(1), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508316477

- Kattari, S. K., Bakko, M., Hecht, H. K., & Kattari, L. (2020). Correlations between healthcare provider interactions and mental health among transgender and nonbinary adults. SSM – Population Health, 10, 100525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100525

- Kelly, J. F., & Westerhoff, C. M. (2010). Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21(3), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.010

- Kidd, J. D., Levin, F. R., Dolezal, C., Hughes, T. L., & Bockting, W. O. (2019). Understanding predictors of improvement in risky drinking in a U.S. multi-site, longitudinal cohort study of transgender individuals: Implications for culturally-tailored prevention and treatment efforts. Addictive Behaviors, 96, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.017

- Knight, L., Xin, Y., & Mengo, C. (2022). A scoping review of resilience in survivors of human trafficking. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1048–1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020985561

- Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., & Kull, R. M. (2015). Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1-2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6

- Kulesza, M., Larimer, M. E., & Rao, D. (2013). Substance use related stigma: What we know and the way forward. Journal of Addictive Behaviors Therapy & Rehabilitation, 02(2), 782. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-9005.1000106

- Kuyper, L., & Bos, H. (2016). Mostly heterosexual and lesbian/gay young adults: Differences in mental health and substance use and the role of minority stress. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(7), 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1071310

- Lee, J. G. L., Shook-Sa, B. E., Gilbert, J., Ranney, L. M., Goldstein, A. O., & Boynton, M. H. (2020). Risk, resilience, and smoking in a national, probability sample of sexual and gender minority adults, 2017, USA. Health Education & Behavior, 47(2), 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119893374

- Lee, S. J. (2015). Addiction and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) issues. In N. el-Guebaly, G. Carrà, & M. Galanter (Eds.), Textbook of addiction treatment: International perspectives. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-88-470-5322-9_98

- Lefevor, G. T., Boyd-Rogers, C. C., Sprague, B. M., & Janis, R. A. (2019). Health disparities between genderqueer, transgender, and cisgender individuals: An extension of minority stress theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(4), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000339

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Lukowski, A. V., Young, S. E., Morris, C. D., & Tinkelman, D. (2016). Characteristics of American Indian/Alaskan native quitline callers across 14 states. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(11), 2124–2129. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw154

- Luoma, J. B., Kohlenberg, B. S., Hayes, S. C., & Fletcher, L. (2012). Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026070

- Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227

- Matsuzaka, S. (2018). Alcoholics anonymous is a fellowship of people: A qualitative study. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 36(2), 152–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2017.1420435

- McCabe, P. C., Dragowski, E. A., & Rubinson, F. (2013). What is homophobic bias anyway? Defining and recognizing microaggressions and harassment of LGBTQ youth. Journal of School Violence, 12(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.731664

- McCabe, S. E., Hughes, T. L., West, B. T., Veliz, P., & Boyd, C. J. (2019). DSM-5 alcohol use disorder severity as a function of sexual orientation discrimination: A national study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(3), 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13960

- McConnell, E. A., Janulis, P., Phillips, G., 2nd, Truong, R., & Birkett, M. (2018). Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority Men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000265

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Ngamake, S. T., Walch, S. E., & Raveepatarakul, J. (2016). Discrimination and sexual minority mental health: Mediation and moderation effects of coping. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000163

- Operario, D., Yang, M-F, Reisner, S. L., Iwamoto, M., & Nemoto, T. (2014). Stigma and the syndemic of HIV-related health risk behaviors in a diverse sample of transgender women. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(5), 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21636

- Ortiz-Hernández, L., Tello, B. L., & Valdés, J. (2009). The association of sexual orientation with self-rated health, and cigarette and alcohol use in Mexican adolescents and youths. Social Science & Medicine, 69(1), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.028

- Pachankis, J. E., Williams, S. L., Behari, K., Job, S., McConocha, E. M., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2020). Brief online interventions for LGBTQ young adult mental and behavioral health: A randomized controlled trial in a high-stigma, low-resource context. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(5), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000497

- Pauly, B. B., Gray, E., Perkin, K., Chow, C., Vallance, K., Krysowaty, B., & Stockwell, T. (2016). Finding safety: A pilot study of managed alcohol program participants’ perceptions of housing and quality of life. Harm Reduction Journal, 13(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-016-0102-5

- Penn, P. E., Brooke, D., Mosher, C. M., Gallagher, S., Brooks, A. J., & Richey, R. (2013). LGBTQ persons with co-occurring conditions: Perspectives on treatment. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 31(4), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2013.831637

- Phillips, G., II, Felt, D., McCuskey, D. J., Marro, R., Broschart, J., Newcomb, M. E., & Whitton, S. W. (2020). Engagement with LGBTQ community moderates the association between victimization and substance use among a cohort of sexual and gender minority individuals assigned female at birth. Addictive Behaviors, 107, 106414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106414

- Pinel, E. C. (1999). Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.114

- Poteat, T., German, D., & Kerrigan, D. (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 84, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019

- Powell, G., Jacobson, G., Schwartz, A., & Barber, M. E. (2011). In translation: Clinical dialogues spanning the transgender spectrum (special issue). Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 15(2), 127–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2011.557648

- Radcliffe, P., & Stevens, A. (2008). Are drug treatment services only for ‘thieving junkie scumbags’? Drug users and the management of stigmatised identities. Social Science & Medicine, 67(7), 1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.004

- Reback, C. J., Veniegas, R., & Shoptaw, S. (2014). Getting off: Development of a model program for gay and bisexual male methamphetamine users. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(4), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.865459

- Reisner, S. L., Pardo, S. T., Gamarel, K. E., White Hughto, J. M., Pardee, D. J., & Keo-Meier, C. L. (2015). Substance use to cope with stigma in healthcare among U.S. female-to-male trans masculine adults. LGBT Health, 2(4), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2015.0001

- Schuler, M. S., Dick, A. W., & Stein, B. D. (2019). Sexual minority disparities in opioid misuse, perceived heroin risk and heroin access among a national sample of US adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 201, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.014

- Schuler, M. S., Rice, C. E., Evans-Polce, R. J., & Collins, R. L. (2018). Disparities in substance use behaviors and disorders among adult sexual minorities by age, gender, and sexual identity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 189, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.008

- Seelman, K. L., Colón-Diaz, M. J. P., LeCroix, R. H., Xavier-Brier, M., & Kattari, L. (2017). Transgender noninclusive healthcare and delaying care because of fear: Connections to general health and mental health among transgender adults. Transgender Health, 2(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0024

- Singer, M., & Clair, S. (2003). Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 17(4), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423

- Sirriyeh, R., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Armitage, G. (2012). Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(4), 746–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x

- Smalley, K. B., Warren, J. C., & Barefoot, K. N. (2015). Barriers to care and psychological distress differences between bisexual and gay men and women. Journal of Bisexuality, 15(2), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2015.1025176

- Smith, L. R., Earnshaw, V. A., Copenhaver, M. M., & Cunningham, C. O. (2016). Substance use stigma: Reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.019

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2015). Behavioral health barometer: United States, 2014 (HHS Publication No. SMA-15-4895). Retrieved March 1, 2023, from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/National_BHBarometer_2014/National_ HBarometer_2014.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2019). Center for behavioral health statistics and quality, substance abuse and mental health services administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS publication no. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf.

- Tebbe, E. A., & Moradi, B. (2016). Suicide risk in trans populations: An application of minority stress theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(5), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000152

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Wang, P. S., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., Kovess, V., Lane, M. C., Lee, S., Levinson, D., Ono, Y., Petukhova, M., … Wells, J. E. (2007). Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. The Lancet, 370(9590), 841–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7

- White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

- Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

- Yang, L. H., Wong, L. Y., Grivel, M. M., & Hasin, D. S. (2017). Stigma and substance use disorders: An international phenomenon. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(5), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000351